Abstract

Aim

To define the demographics and clinical characteristics of cases presenting with nutritional rickets to paediatric centres in Sydney, Australia.

Methods

Retrospective descriptive study of 126 cases seen from 1993 to 2003 with a diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency and/or confirmed rickets defined by long bone x ray changes.

Results

A steady increase was seen in the number of cases per year, with a doubling of cases from 2002 to 2003. Median age of presentation was 15.1 months, with 25% presenting at less than 6 months of age. The most common presenting features were hypocalcaemic seizures (33%) and bowed legs (22%). Males presented at a younger age, with a lower weight SDS, and more often with seizures. The caseload was almost exclusively from recently immigrated children or first generation offspring of immigrant parents, with the region of origin predominantly the Indian subcontinent (37%), Africa (33%), and the Middle East (11%). Seventy nine per cent of the cases were born in Australia. Eleven cases (all aged <7 months) presented atypically with hyperphosphataemia.

Conclusions

This large case series shows that a significant and increasing caseload of vitamin D deficiency remains, even in a developed country with high sunlight hours. Cases mirror recent immigration trends. Since birth or residence in Australia does not appear to be protective, screening of at risk immigrant families should be implemented through public health policies.

Keywords: rickets, vitamin D deficiency

Despite a clearer understanding of predisposing factors and attempts at preventative strategies, nutritional rickets has made a surprising resurgence in many parts of the world. Recent reports have not only come from temperate regions with limited sunshine such as Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and USA,1,2,3,4 but also from sunnier climates such as Australia, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia.5,6

Vitamin D deficiency rickets is easily treated once it has been recognised, however it has significant potential for morbidity and mortality including hypocalcaemic seizures, failure to thrive, increased susceptibility to serious infections, and potential for chronic problems with growth and skeletal deformity.7 Various nutritional, ethnic, cultural, and societal factors are likely to account for either an increase in the prevalence of rickets or increasing recognition,7 with different factors likely to predominate in different regions. The belief that nutritional rickets has been eliminated from developed societies is widespread and can inhibit recognition, appropriate management, and institution of preventative strategies.

In view of a major increase in the number of cases presenting to paediatric centres in Sydney, Australia, we sought to define further the demographics and clinical characteristics of this group. In particular we sought to explore the impact of migration factors and further characterise features in an atypical group of infants with hyperphosphataemia at presentation.

Methods

We undertook a retrospective, descriptive study from 1993 to 2003 (11 years). Cases were ascertained from three major teaching hospitals in Sydney (The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney Children's Hospital, and St George Hospital) through a search of hospital endocrine and medical record databases and notification of cases from paediatricians and paediatric endocrinologists. Inclusion criteria were a final diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency (defined as vitamin D <50 nmol/l) and/or confirmed rickets defined by long bone x ray changes, such as cupping, splaying, and fraying of the metaphysis. Exclusion criteria were rickets secondary to malabsorptive disorders, renal tubular disorders, hereditary vitamin D dependent rickets, and hereditary hypophosphataemic rickets. All patients included responded to vitamin D therapy. While this was not a prevalence ascertainment study, we believe it captures a majority of hospital presenting cases in the Sydney region.

Data obtained from the medical record included date of birth, age and month of presentation to hospital, weight and length/height on presentation, region of origin, place of birth, length of time in Australia, gestational age, birth weight, method of presentation, diet including maternal diet, sun exposure, maternal vitamin D status, biochemistry (total calcium phosphate, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 25‐hydroxyvitamin D, 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone (PTH), full blood count (FBC), and ferritin), and x ray signs. Vitamin D was measured by commercial radioimmunoassays (Diasorin, Stillwater, MN) which for 25‐hydroxyvitamin D detects both ergocalciferol and cholecalciferol. We chose to use region of origin for categorisation rather than ethnicity because of the difficulties posed by increasing rates of mixed ethnicity.

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 11.5.1. Normally distributed variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Skewed data are reported as median ± range. Independent t tests and ANOVA were used to compare normally distributed continuous variables and Mann‐Whitney U for skewed variables. The χ2 test was used for analysis of categorical data. Standard deviation scores (z scores) for height and weight were determined from age and sex specific reference values.8 Birth weight was categorised as either small for gestational age (SGA) (<10th centile), appropriate for gestational age (AGA), or large for gestational age (LGA) (>90th centile).

Results

Clinical and demographic

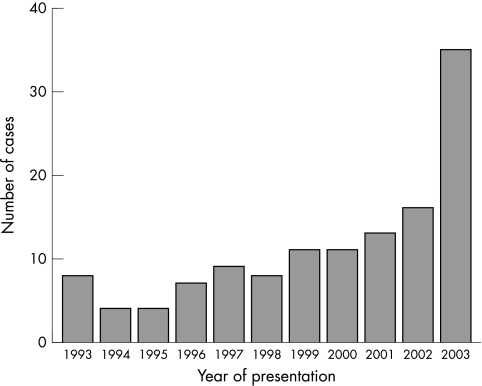

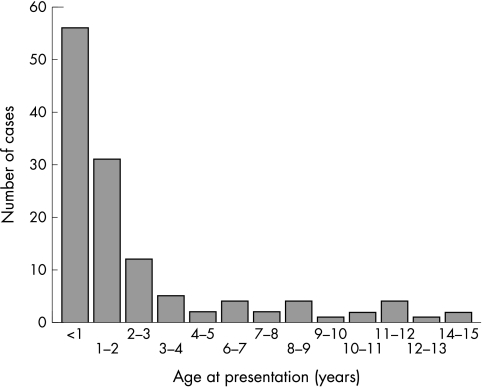

One hundred and twenty six cases were included in the analysis from the 11 year period. A steady increase was seen in the number of cases over the study period, with a doubling of cases from 2002 to 2003 (fig 1). Males accounted for 64% of cases and they presented at a significantly younger age, 10.8 v 22.5 months for females (p < 0.001). The median age of presentation was 15.1 months. Twenty five per cent presented at less than 6 months of age, 44% at less than 12 months, and 66% under the age of 2 years (fig 2).

Figure 1 Cases of rickets presenting per year in Sydney, 1993–2003.

Figure 2 Age at presentation.

Presenting clinical features are shown in table 1, with the most common being hypocalcaemic seizures (33%), bowed legs (22%), and sibling diagnosis (18%). In the hypocalcaemic seizure group, 50% presented at less than 6 months (accounting for 66% of presentations less than 6 months) and 85% at less than 1 year of age. Males presented with hypocalcaemic seizures in 43.8% of cases compared to only 15% of females (p = 0.001). In the hypocalcaemic group, the median total calcium was 1.38 mmol/l (range 1.09–1.93) and the levels of 25‐hydroxyvitamin D (95% <20 nmol/l) were lower compared to those presenting with other manifestations. Eight cases were diagnosed incidentally; four of these presented with chest infection, a rarer, but recognised method of presentation.7 The seven children presenting with failure to thrive did so before the age of 2 years, and four of these in the first 6 months of life. A higher percentage of SGA babies were seen in this subgroup (4/7), with all cases breast fed by severely vitamin D deficient mothers (25‐hydroxyvitamin D <20 nmol).

Table 1 Clinical characteristics at presentation.

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Method of presentation | % (n/N) |

| Hypocalcaemic seizure | 33.3 (42/126) |

| Bowed legs | 22.2 (28/126) |

| Sibling diagnosis | 18.3 (23/126) |

| Failure to thrive | 5.6 (7/126) |

| Delayed motor development | 5.6 (7/126) |

| Fractures | 4.0 (5/126) |

| Bone pain | 4.0 (5/126) |

| Incidental finding | 3.2 (4/126) |

| Chest infection | 3.2 (4/126) |

| Chronic medical problems | 0.8 (1/126) |

| Growth parameters | Mean (SD) |

| Weight z score | −0.85 (1.44) |

| Height z score (97/126 available) | −1.01 (1.68) |

| Birth weight | % (n/N) |

| SGA | 23.0 (18/77) |

| AGA | 59.0 (46/77) |

| LGA | 18.0 (13/77) |

The overall cohort were smaller than the general population in both weight and height parameters (p < 0.001) (table 1). There was a higher percentage of SGA babies (birth weight <10th centile for gestational age), compared to expected rates in the normal population. Only 8% of the total group (for whom gestation was available) were born prematurely.

Both the sibling diagnosed and white Australian group were less severely affected. The white Australian group presented more sub‐acutely, with bowed legs, incidental diagnosis, fractures, and failure to thrive. Biochemically there was a lesser degree of secondary hyperparathyroidism in both these groups, with 8/13 siblings diagnosed having normal PTH levels accompanied by normal x rays, where performed. The white Australian children ranged in age from 3 months to 14 years and all had low reported exposure to sunshine.

Region of origin and environmental factors are summarised in table 2. The most prominent regions of origin were the Indian subcontinent (37%), Africa (33%), and the Middle East (11%). The caseload was almost exclusively recently immigrated children or first generation offspring of immigrant parents, with only five white Australian children (4% of the total) diagnosed. Seventy nine per cent of the cases were born in Australia.

Table 2 Region of origin and environmental factors.

| Characteristic | % (n/N*) |

|---|---|

| Region of origin | |

| Indian subcontinent | 36.6 (45/123) |

| Middle East | 32.5 (41/123) |

| African | 11.2 (14/123) |

| Polynesian | 7.1 (9/123) |

| Australia (white Australian) | 4.0 (5/123) |

| Northern Asia | 3.2 (4/123) |

| South East Asia | 3.2 (4/123) |

| Central Asia | 0.8 (1/123) |

| Dietary history | |

| Breast fed | 70.7 (75/106) |

| Exclusively breast fed | 31.1 (33/106) |

| Prolonged breast feeding >1 year | 24.5 (26/106) |

| Sunlight exposure | |

| Minimal | 53.1 (51/96) |

| None | 35.4 (34/96) |

| Normal | 11.5 (11/96) |

| Born in Australia | 79.1 (88/110) |

| If not, time spent in Australia | |

| <1 year | 77.3 (17/22) |

| 1–5 years | 18.2 (4/22) |

| >5 years | 4.3 (1/22) |

*The denominator indicates the number of subjects in each category for whom data were available.

There was seasonal variation in the caseload, with 68% (86/126) of cases presenting in the winter or spring (June to November). Hypocalcaemic seizures were more common in the winter and spring (40% of total cases) than summer and autumn (20%, p < 0.001). No or minimal sunlight exposure was reported in 89% (85/96). Of those with reported decreased sunlight exposure, 82% had 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels of <20 nmol/l.

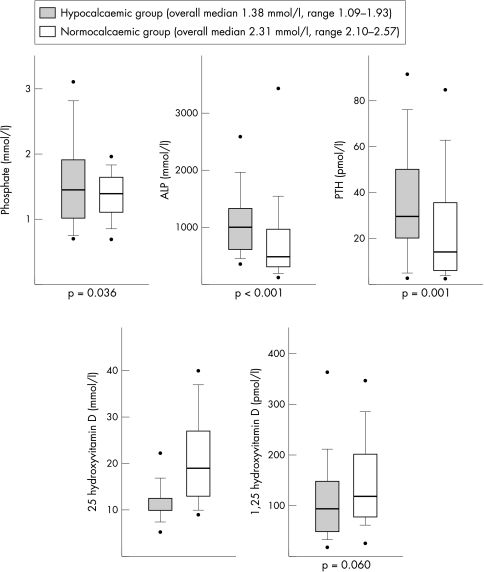

Biochemistry (fig 3)

Figure 3 Biochemical features based on hypocalcaemia or normocalcaemia at presentation. For the purposes of graphical representation, values of 25‐hydroxyvitamin D less than the lower detection limit are displayed as the detection limit, and therefore a significance value is not displayed for 25‐hydroxyvitamin D. Boxes show median, 25th and 75th centiles; whiskers show 10th and 90th centiles; dots show 5th and 95th centiles.

25‐Hydroxyvitamin D levels were <20 mmol/l in 73% (90/123), and were significantly lower in the <6 month age group (88% v 68% < 20 nmol/l, p = 0.033). Hypocalcaemia was present in 52% (65 of 124) at presentation. In the hypocalcaemic group, of which 63% (41 of 65) presented with seizures, 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels were <20 mmol/l in 94%, compared to only 51% of the normocalcaemic group (p = 0.02). Phosphate levels at presentation were noted to be significantly higher in those <6 months (mean 1.90 mmol/l, SD 0.80) compared to those >6 months (mean 1.32 mmol/l, SD 0.39, p < 0.001). Eleven cases of hyperphosphataemia were identified, all <7 months of age. No other biochemical parameter showed significant differences between age groups.

PTH was raised in 80% of cases (84/105). Some children with very low 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels showed no significant PTH response. ALP was raised in 82% (100/122) of cases. When measured, 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D was low in 6% (3/53), normal in 53% (28/53), and raised in 41% (22/53) of cases.

FBC was performed in 98 cases within one month of presentation and diagnosis. There were 20 definite cases of iron deficiency anaemia and 10 suggestive (microcytic anaemia but no serum ferritin measured), representing 31% of the cases. In four cases, ferritin levels were initially normal, but fell subsequently into the deficient range, implying that the initially normal ferritin was part of an acute phase response. None of these included cases with iron deficiency were subsequently found to have coeliac disease or other causes of malabsorption.

All 63 mothers tested were vitamin D deficient (25‐hydroxyvitamin D <50 nmol/l), with 68% (43/63) having a 25‐hydroxyvitamin D level of <20 nmol/l. Of the mother–infant pairs with 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels, 91% of the paediatric cohort had a level of <20 nmol/l if breast fed by a vitamin D deficient mother, and 94% if exclusively so.

Radiology

There was x ray evidence of rickets in 78% (83/106) and a further 8% (8/106) showed evidence of osteopenia. Eighty six per cent of patients presenting with 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels <20 nmol/l and 84% of hypocalcaemic patients had x ray changes consistent with rickets. Of the 12 normal radiographs, 50% had evidence of secondary hyperparathyroidism (raised PTH and ALP).

Discussion

This is the largest case series of vitamin D deficient rickets reported to date from a developed country. Recently immigrated infants or first generation offspring of immigrant parents, with maternal vitamin D deficiency and exclusive or prolonged breast feeding were prominent in this series, and males were more commonly affected. The observed increase mirrors immigration trends, and while increased awareness of vitamin D deficiency and rickets/osteomalacia in Australia in recent years6,9,10,11 may have contributed to increase case detection, it is of concern that severe infantile and childhood6,11 manifestations have continued.

Immigration trends over the last decade have shown a demographic shift in region of origin, with a major increase from North African, Middle Eastern, and Asian countries.12 Over the last two years of the study period, North African and Middle Eastern immigration rose by 76%, the largest increase of any ethnic group. The number of African children presenting, predominantly North African, rose from four cases in each of 2001 and 2002 (25% and 30% of total cases respectively), to 22 cases in 2003 (62% of total cases). The prevalence of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in adult women in these regions is well reported.5,13,14 Furthermore, 74% of pregnant women from the Horn of Africa had 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels <25 nmol/l, in a study from Melbourne.15 These high maternal risk factors persist, even though the majority of our cohort (79%) were born in Australia. Vitamin D levels are not performed as part of the screening process for immigrants arriving in Australia and data do not exist on the effect of residing in Australia on maternal vitamin D levels after immigration. It is likely that vitamin D levels drop further in immigrant women after arriving in Australia, with less time spent outdoors.16

Research has shown that 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels of 50 nmol/l are required to prevent secondary hyperparathyroidism,17 while the level for optimal skeletal health may be as high as 80 nmol/l.18 Many commercial assays currently show lower normal reference ranges considerably below this. Reduced sunlight exposure is an important factor in the aetiology of vitamin D deficiency, as intake from dietary sources, such as oily fish, eggs, and butter/margarine,19 account for only 10% of the daily requirement.20 Human milk supplies less than 100 IU vitamin D/day in vitamin D sufficient mothers.21,22,23 Sydney has an annual daily average of 6.95 hours of sunlight, with 6.58 hours per day in winter,24 easily adequate for the recommended 30 minutes per week, wearing only a nappy, or 2 hours a week fully clothed without a hat, in infants.23 The swaddling of babies, poor accommodation, ethnic and religious practices, and campaigns to decrease sunlight exposure may all increase the risk of rickets.25 Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is 12–15% higher in Australia compared to similar locations in the northern hemisphere,26 with skin cancer rates among the highest in the world. UV light does not penetrate clothing or glass and sunscreen affects vitamin D status. Sunscreen with a UV protection factor of 8 reduces the skin's ability to produce vitamin D by 97.5%17 and 15+ sunscreens are commonly used in Australia. Darkly pigmented individuals are further compromised with melanin competing with 7‐dehydrocholesterol in the skin for UV‐B photons, resulting in a highly increased requirement for sun exposure to achieve the same vitamin D levels.27 Differences have been shown between light and dark skinned individuals in milk cholecalciferol, ergocalciferol, and 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels.22

Almost two thirds of cases in the present study were male, who presented earlier and more acutely than females. A male predominance has been shown in previous retrospective studies, in Australia, Ethiopia, and the USA,6,14,28,29 but not uniformly, with a Copenhagen based study showing a large female predominance.30 The reasons for the male predominance are unclear and immigration gender ratios do not account for this.12 Significantly more males were breast fed and exclusively breast fed, and this may reflect preferential treatment given to male children, which is recognised in some cultures. Vitamin D deficiency negatively affects growth and is a recognised cause of failure to thrive. Children affected by rickets are smaller, both in height and weight, than the normal population.7 In this cohort, males had a significantly lower weight z score, compared to females, which has not been reported previously.

The increasing frequency of rickets in the UK has recently been highlighted4,31 with Ladhani et al reporting data on 65 cases. We found the same major early peak of presentation, although Ladhani et al reported a small additional adolescent peak with hypocalcaemic presentation. Peak presentation in winter and spring was more evident in our patient group. We reported a higher rate of x ray changes of rickets in hypocalcaemic subjects (84%) compared with the UK study (41%). We also found that PTH was significantly higher in the hypocalcaemic subjects in our study; however six hypocalcaemic subjects did not have elevated PTH, perhaps reflecting assay or blood collection issues.

As has been noted by others,4,32 we also identified a subset of 11 cases with hyperphosphataemia, all aged less than 7 months. In some cases this had caused initial diagnostic confusion with hypoparathyroidism, since vitamin D and PTH levels were not available for up to two weeks after sampling. Each case presented with profound hypocalcaemia, hypocalcaemic seizures, and subsequently all had vitamin D levels of <20 nmol/l. In 8 of the 10 cases where PTH levels were available, PTH levels were raised (median 28 pmol/l, range 2.8–80). Suggested mechanisms for this phenomenon include refractoriness of bone to PTH after prolonged vitamin D deficiency33 and diminished response of renal cyclic adenosine monophosphate to PTH,34 which is further diminished in hypocalcaemia.35 The lower urinary excretion of phosphate noted in exclusively breast fed infants compared to formula fed infants may be a contributing factor.29 Also of note in our subjects was the great variability of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D levels (when measured) as previously reported,17 highlighting its limited value for diagnosis. This most likely reflects transient peaks due to rapid conversion of 25‐hydroxyvitamin D after vitamin D intake or short periods of sunlight exposure and the short half‐life of 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D, with these transient effects not being exerted on bone or kidney.

The data presented in this study do not fully reflect the characteristics or prevalence of rickets in Sydney, due to incomplete ascertainment. Nevertheless the large numbers highlight the need to understand the changing demographics and public health issues associated with vitamin D deficient rickets. Maternal dietary history was not consistently recorded, and the classification of sunlight exposure is subjective. Calcium deficiency has been found to play a major role in Nigerian children with rickets, with only one third of rickets phenotype children having 25‐hydroxyvitamin D levels <30 nmol/l, and treated using both calcium and vitamin D supplementation.36 The impact of calcium intake in Australia is unclear and was not assessed in this cohort. The difficulties of 25‐hydroxyvitamin D and PTH measurement, with variation in accuracy among different assays, as well as laboratory assay experience,37 could have contributed to the inconsistent relationship between PTH and 25‐hydroxyvitamin D.

The American Academy of Pediatrics38 recently released guidelines for vitamin D intake, recommending that all infants have a minimum intake of 200 IU of vitamin D daily, beginning in the first 2 months of life and continuing through to adolescence. For infants not meeting this intake, supplementation was recommended, including all substantially breast fed infants and non‐breast fed infants who are not ingesting adequate vitamin D fortified formula or milk. Supplementation was also recommended for children and adolescents who do not get regular sunlight exposure. Despite a recognised need,39 no similar recommendations currently exist in Australia. Treatment and counselling in pregnancy was found to be inadequate in a Melbourne study, with 40% of infants aged 4–12 months found to be vitamin D deficient (25‐hydroxyvitamin D <50 mmol/l), and those breast fed more severely affected.16

We have shown a dramatic increase in the presentation of vitamin D deficient rickets to major paediatric centres in Sydney, a large, modern city with good nutritional and health standards and relatively high sunlight hours. Health practitioners need to be re‐educated about this condition and be aware of groups at risk, including other family members who are likely to have subclinical vitamin D deficiency. Infants with severe vitamin D deficiency are likely to present early with seizures and there is a subgroup of these in which hyperphosphataemia may cause initial diagnostic confusion. The public health issues have not yet been adequately addressed; consideration should be given to screening at risk immigrant groups, education programmes, and supplementation, if these increasing trends are to be reversed.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none

References

- 1.Blok B H, Grant C C, McNeil A R.et al Characteristics of children with florid vitamin D deficient rickets in the Auckland region in 1998. N Z Med J 2000113374–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowe P M. Why is rickets resurgent in the USA? Lancet 20013571100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw N J, Pal B R. Vitamin D deficiency in UK Asian families: activating a new concern. Arch Dis Child 200286147–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladhani S, Srinivasan L, Buchanan C.et al Presentation of vitamin D deficiency. Arch Dis Child 200489781–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karrar Z A. Vitamin D deficiency rickets in developing countries. Ann Trop Paediatr 199818(suppl)S89–S92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nozza J M, Rodda C P. Vitamin D deficiency in mothers of infants with rickets. Med J Aust 2001175253–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wharton B, Bishop N. Rickets. Lancet 20033621389–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention www.cdc.gov/needphp/dnpa/growthcharts , 2004, 2005

- 9.Grover S R, Morley R. Vitamin D deficiency in veiled or dark‐skinned pregnant women. Med J Aust 2001175251–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason R S, Diamond T H. Vitamin D deficiency and multicultural Australia. Med J Aust 2001175236–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plehwe W E. Vitamin D deficiency in the 21st century: an unnecessary pandemic? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 20035922–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Australian Bureau of Statistics Migration 2002–3. www.abs.gov.au 2003

- 13.Elzouki A Y, Markestad T, Elgarrah M.et al Serum concentrations of vitamin D metabolites in rachitic Libyan children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 19899507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lulseged S. Severe rickets in a children's hospital in Addis Ababa. Ethiop Med J 199028175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skull S A, Ngeow J Y, Biggs B A.et al Vitamin D deficiency is common and unrecognized among recently arrived adult immigrants from The Horn of Africa. Intern Med J 20033347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson K, Morley R, Grover S R.et al Postnatal evaluation of vitamin D and bone health in women who were vitamin D‐deficient in pregnancy, and in their infants. Med J Aust 2004181486–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holick M F. Vitamin D: the underappreciated D‐lightful hormone that is important for skeletal and cellular health. Current Opinion in Endocrinology and Diabetes 2002987–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holick M F. Sunlight “D”ilemma: risk of skin cancer or bone disease and muscle weakness. Lancet 20013574–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Truswell A S, Dreosti I E, English R M.Recommended nutrient intakes, Australian papers. Sydney: Australian Professional Publications, 1990

- 20.Holick M F. Vitamin D: a millennium perspective. J Cell Biochem 200388296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hillman L S. Mineral and vitamin D adequacy in infants fed human milk or formula between 6 and 12 months of age. J Pediatr 1990117S134–S142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Specker B L, Tsang R C, Hollis B W. Effect of race and diet on human‐milk vitamin D and 25‐hydroxyvitamin D. Am J Dis Child 19851391134–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Specker B L, Valanis B, Hertzberg V.et al Sunshine exposure and serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in exclusively breast‐fed infants. J Pediatr 1985107372–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Australian Bureau of Meteorology www.bom.gov.au 2005

- 25.Belton N R. Rickets—not only the “English disease”. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 198632368–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gies P, Roy C, Javorniczky J.et al Global solar UV index: Australian measurements, forecasts and comparison with the UK. Photochem Photobiol 20047932–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clemens T L, Adams J S, Henderson S L.et al Increased skin pigment reduces the capacity of skin to synthesise vitamin D3. Lancet 1982174–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipson A H. Epidemic rickets in Sydney. Aust Paediatr J 1973914–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobsen S T, Hull C K, Crawford A H. Nutritional rickets. J Pediatr Orthop 19866713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedersen P, Michaelsen K F, Molgaard C. Children with nutritional rickets referred to hospitals in Copenhagen during a 10‐year period. Acta Paediatr 20039287–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allgrove J. Is nutritional rickets returning? Arch Dis Child 200489699–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson D, Flynn D, Dandona P. Hyperphosphataemic rickets in an Asian infant. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 19852901318–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah B R, Finberg L. Single‐day therapy for nutritional vitamin D‐deficiency rickets: a preferred method. J Pediatr 1994125487–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewin I G, Papapoulos S E, Hendy G N.et al Reversible resistance to the renal action of parathyroid hormone in human vitamin D deficiency. Clin Sci (Lond) 198262381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rao D S, Parfitt A M, Kleerekoper M.et al Dissociation between the effects of endogenous parathyroid hormone on adenosine 3′,5′‐monophosphate generation and phosphate reabsorption in hypocalcemia due to vitamin D depletion: an acquired disorder resembling pseudohypoparathyroidism type II. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 198561285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thacher T D, Fischer P R, Pettifor J M.et al Case‐control study of factors associated with nutritional rickets in Nigerian children. J Pediatr 2000137367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollis B W. Editorial: The determination of circulating 25‐hydroxyvitamin D: no easy task. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004893149–3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gartner L M, Greer F R. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency: new guidelines for vitamin D intake. Pediatrics 2003111908–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowell C T. Vitamin D deficient rickets in children—a preventable nutritional disorder. Med J Aust 2003178467–468.12720500 [Google Scholar]