Following the adverse publicity regarding MMR vaccine,1 MMR vaccination rates have declined. Kingston had the highest uptake of MMR in London (83–87% in 2003–04), but is still below the national target.2 A targeted MMR Capital Catch up Campaign was introduced by the London NHS for the estimated 90 000 primary school children (aged 4–11 years) susceptible to measles (received less than two doses).

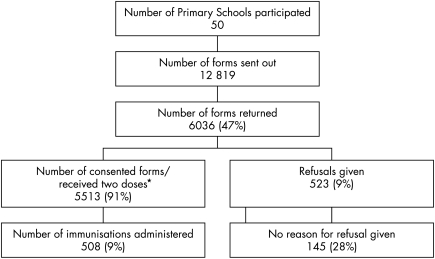

We conducted a descriptive study looking at parents' reasons for refusing MMR vaccination, analysing retrospectively all returned consent forms, from 50 primary schools from the Royal Borough of Kingston (fig 1), between December 2004 and April 2005. Parents were asked to indicate one of three options: consent to vaccination; refusal of vaccination; or no need for vaccination (as child had already received two doses of MMR). They were also given access to evidence based information on the MMR vaccination. Parents who refused consent were invited to state the reason(s) why. For the purpose of the study, the forms were anonymised to ensure confidentiality. Consequently individual follow up of cases was not possible.

Figure 1 Profile of MMR Catch up Campaign in the Royal Borough of Kingston. There were no accurate baseline data on previous MMR immunisations; therefore all children were targeted in the 50 participating schools. Consent forms were given to children in schools to hand to their parents. Completed forms were handed back to school. For the purpose of the study, the forms were anonymised to ensure confidentiality. Reasons for refusal were analysed using Excel. *These two groups were counted together.

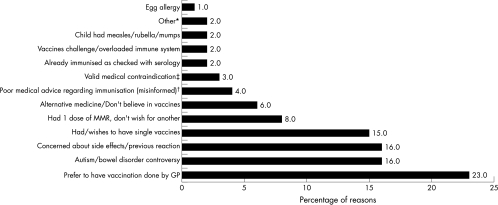

All children were targeted because of poor baseline data on previous MMR immunisations. We summarised the responses into 13 different categories (fig 2). Of the main reasons given, 23% stated they wished to be present with their children during the vaccination and would prefer to have the vaccination done at the GP surgery. The autism/bowel disorder controversy scored highly (16%), as did concern regarding side effects of the vaccine or previous reactions. Three per cent stated a medical contraindication, such as receiving immunosuppressive therapy or immunoglobulin injections, and 4% of refusals were from poor medical advice (fig 2). Only 9% of those who returned their forms (47%) did not provide consent for immunisation. We are unaware of the motives of parents who did not return their forms (53%). Of the target population, 2.9% gave reasons for refusal to consent.

Figure 2 Reasons for refusal of consent to vaccination. *Objection to the munufacturing process of the rubella component, requests for serology prior to vaccination. †Egg allergy, multiple food allergies, family/personal history of convulsions. ‡Immunosuppressive therapy (chemotherapy, high dose steroid therapy, immunosuppressive drugs), immunoglobulin injections.

The results from our study reflect the findings of similar previous studies,3,4,5 namely “alternative views” on immunisation, the influence of the media, and mistrust of the advice of health professionals and the government. We suggest that intense educational programmes are set up locally for health professionals and the public, prior to any future catch up campaigns. Uptake could also be improved by arranging a more reliable distribution of the consent form, notice of intended campaigns, and a choice of venue for immunisation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Kingston PCT for allowing them access to their data, Frances Peppler, Audit Facilitator, Kingston Hospital for helping with the design of the study and data analysis, Dr Barry Walsh for his support and advice, and Dr Paul Heath for his comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Wakefield A J, Murch S H, Anthony A.et al Ileal‐lymphoid‐nodular hyperplasia, non specific colitis and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet 1998351637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren L, Beytell H, Walsh B. Immunisation uptake in South West London (Oct02–June04). COVER (Cover for Vaccination Evaluated Rapidly). Health Protection Agency 200421–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lunts E, Cowper D. Parents refusing MMR: do GPs and health visitors understand why? Community Practitioner 200275(3)43–45. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrovic M, Roberts R J, Ramsay M.et al Parents attitude towards the second dose of measles, mumps and rubella vaccine: a case control study. Commun Dis Public Health 20036325–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMurray R, Cheater F M, Weighall A.et al Managing controversy through consultation: a qualitative study of communication and trust around MMR vaccination decisions. Br J Gen Pract 200454520–525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]