Abstract

Background

Coeliac disease (CD) is a disorder that may depend on genetic, immunological, and environmental factors. Recent observational studies suggest that breast feeding may prevent the development of CD.

Aim

To evaluate articles that compared effects of breast feeding on risk of CD.

Methods

Systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies published between 1966 and June 2004 that examined the association between breast feeding and the development of CD.

Results

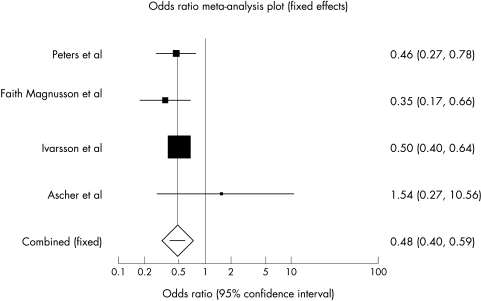

Six case‐control studies met the inclusion criteria. With the exception of one small study, all the included studies found an association between increasing duration of breast feeding and decreased risk of developing CD. Meta‐analysis showed that the risk of CD was significantly reduced in infants who were breast feeding at the time of gluten introduction (pooled odds ratio 0.48, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.59) compared with infants who were not breast feeding during this period.

Conclusions

Breast feeding may offer protection against the development of CD. Breast feeding during the introduction of dietary gluten, and increasing duration of breast feeding were associated with reduced risk of developing CD. It is, however, not clear from the primary studies whether breast feeding delays the onset of symptoms or provides a permanent protection against the disease. Long term prospective cohort studies are required to investigate further the relation between breast feeding and CD.

Keywords: breast feeding, coeliac disease, systematic review, meta‐analysis

Coeliac disease (CD), also known as gluten sensitive enteropathy, is defined as a permanent intolerance to gluten, a protein found in cereals such as wheat, rye, and barley, associated with mucosal disease of the proximal small bowel.1 The true prevalence of CD is difficult to ascertain as many affected people are asymptomatic. In a recent UK paediatric study, Bingley et al found that, based on IgA endomyseal antibody testing, the prevalence of CD in children aged 7 years was 1%, a figure comparable to the prevalence in UK adults.2

CD is characterised by intestinal malabsorption, histological abnormalities of the small bowel mucosa, clinical and histological improvement on a gluten‐free diet, and a relapse on a gluten containing diet. The condition is entirely dependent on the presence of gluten in the diet, but exactly why some people develop the disorder on ingestion of gluten and others do not is unclear. While it is known that genetic factors play a role in the development of the disease, it is believed that something in the environment triggers the immune system of infants making them prone to the subsequent development of CD.2

Recent epidemiological studies suggest that early infant feeding practices may be important environmental risk factors for the subsequent development of CD. In a recent case‐control study, Ivarsson et al examined whether breast feeding and the mode of introduction of gluten influenced the risk of CD in 627 Swedish children with CD compared with 1254 controls.3 They found that the risk of the disease was reduced in children if they were breast feeding at the time of introduction of dietary gluten. Peters et al4 and Auricchio et al5 also showed that breast feeding was associated with a reduced risk of developing childhood CD. While these and other observational studies have suggested that breast feeding might reduce the risk of CD, at least one study did not find such an association.6

In this study, we sought to explore the potential association between breast feeding and reduced risk of CD by conducting a systematic review and meta‐analysis. In particular, we looked for the following effects: (1) the effect of breast feeding, compared with no breast feeding; (2) the effect of duration of breast feeding; and (3) the effect of breast feeding at the time of introduction of dietary gluten.

Methods

Types of studies

We included observational studies if they: (1) compared risk of CD in people who were breast fed with risk in those who were not breast fed, or compared risk of CD according to duration of breast feeding; (2) had used histological criteria for diagnosing CD; (3) had controlled for potential confounders by matching in the study design or used risk adjustment in the analysis; and (4) had provided sufficient data to allow the reconstruction of 2×2 tables or to determine relative risks (RR) or odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Search strategy

We systematically searched Medline (1966–May 2004), Embase (1980–May 2004), and Cinahl (1982–May 2004) for both English and non‐English language articles.

Medline on Pubmed was searched using the following search strategy:

Coeliac disease OR celiac disease OR gluten enteropathy OR sprue

Celiac disease[MESH]

1 OR 2

Breastfeeding OR Breast feeding OR Breast‐feeding

Breast feeding[MESH]

4 OR 5

3 AND 6

Embase on Ovid was searched using the following strategy:

Coeliac disease OR celiac disease OR gluten enteropathy OR sprue

exp celiac disease/all subheadings

1 OR 2

Breastfeeding OR breast feeding OR breast‐feeding

Exp breast feeding/all subheadings

4 OR 5

3 AND 6

Cinahl on Ovid was searched using a strategy similar to the above Embase search strategy.

We then searched the reference lists of all relevant articles retrieved from the computerised database search to find other potentially relevant articles. We also contacted experts in the field in order to try to identify other studies (published or unpublished). The titles and/or abstracts of all identified studies were reviewed and full manuscripts obtained for those that appeared potentially relevant.

Assessment of study eligibility

Two reviewers (AKA and AVR) independently assessed each article for eligibility using the inclusion criteria above. Disagreement among reviewers was discussed and agreement reached by consensus.

Assessment of methodological quality

Two investigators independently rated the methodological quality of selected studies using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Oxford, UK) tool for case‐control studies.7 We recorded each quality assessment criterion as being “met”, “unmet”, or “unclear”. However, as several criteria were used to assess validity, these were summarised to derive an overall assessment of how valid the results of each study were by grading them as A (low risk of bias), B (moderate risk of bias), or C (high risk of bias) according to published criteria.8

Data extraction

A data abstraction form was developed and used to extract information on relevant features and results of included studies. Two reviewers independently extracted and recorded data using a predefined checklist. When data were missing or unclear in a paper, attempts were made to contact the authors for more information.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using StatsDirect statistical software (version 2.3.5). Individual OR and their 95% CI from each case‐control study were calculated. Where possible, a pooled OR with 95% CI was calculated. The meta‐analysis was conducted using the Mantel‐Haenszel method.9

Heterogeneity

The statistical validity of combining the results of the various trials was assessed by examining the homogeneity of the outcomes from the various trials. This was carried out by: (1) a χ2 test of homogeneity of the OR; and (2) inspection of the graphical display.

Sensitivity analysis

As tests of heterogeneity may be underpowered to detect heterogeneity between studies when the number of studies is small,10 we performed a sensitivity analysis based on random effects versus fixed effects models. We used the random effects model to also calculate pooled ORs and 95% CIs because this model may account for heterogeneity between studies.11

Publication bias

We originally planned to use funnel scatter plots to assess the possibility of publication bias. However, there were only four studies whose results could be pooled and we considered these to be too few to allow a proper assessment of publication bias. As Sutton et al have suggested, up to five studies are usually too few to allow the detection of an asymmetric funnel.12

Results

We identified 15 potentially relevant articles on the association between breast feeding and the development of CD. Nine articles were excluded for various reasons. Three articles were excluded because they were review articles.13,14,15 Four studies were excluded because they were retrospective studies of children with CD without control groups.16,17,18,19 The paper by Challacombe et al was excluded because it only investigated the relations between changing infant feeding practices and the incidence of CD.20 A ninth study was excluded because it was a short letter with insufficient information provided on study methodology.21

Six studies were identified that satisfied the inclusion criteria and these were included in the review.3,4,5,6,22,23 All the included studies were case‐control studies. No cohort study was found on the subject. All the included studies compared the breast feeding history of participants with CD with those not known to have CD. Cases had been diagnosed to have CD based on small intestinal biopsy. All the studies had used questionnaires or interviewing techniques to elicit infant feeding history from parents/carers.

Methodological quality of included studies

Due to the retrospective design, all the studies were prone to recall bias. All the included studies except the one by Ascher et al6 used healthy children who had not had small intestinal biopsies as controls, but because CD can be asymptomatic, it is possible for some controls to have been misclassified. A summary of the methodology of the included studies is shown in table 1. The methodological quality of each study was summarised using the categories described above. All the six included studies were graded “B”.

Table 1 Methodology of included studies (summary).

| Reference (country) | Case selection | Control selection | Exposure measurement | Confounding factors considered | Sample size | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greco et al22 (Italy) | Children with CD in Campania region, Italy | Healthy children from the same region. | Interview by one of the authors | Age and area of residence, age at gluten introduction, father's occupation | 201 cases, 1949 controls | Cases, mean 2.14 years, SD, 2.6; controls, 2.34, SD, 2.93 |

| Peters et al4 (Germany) | From a CD incidence study and appeals at a national meeting. | Identified through a population registry | Questionnaire | Age, sex, number of inhabitants in area, FH of CD, age at gluten introduction | 143 cases, 137 controls | Mean age 6.4 years (median 6.2) |

| Falth‐Magnusson et al23 (Sweden) | Children with CD in participating centres | Healthy children living in the same region selected. | Questionnaire | Age, area of residence | 72 cases, 264 controls | Median age 3.1 years (range 1.4–5.1) |

| Ivarsson et al3 (Sweden) | Children on CD database | Selected through national population register | Questionnaire | Age, sex, area of residence, other infant feeding practices | 491 cases, 781 controls | Age range of participants was 0–14.9 years |

| Auricchio et al5 (Italy) | Cases in participating centres who had healthy siblings | Siblings of cases without symptoms of CD | Interview | Not specifically stated but by using sibling controls, some genetic, environmental and socioeconomic factors might have been controlled for | 216 cases, 289 controls | Median age at diagnosis 15 months (range 6 months to 14 years). |

| Ascher et al6 (Sweden) | Siblings of known CD patients found to have HLA genotype DQA1*0501‐DQB1*02 and CD on screening | Siblings with the HLA genotype but who did not have CD on small intestinal biopsy | Interview | Controlled for HLA genotype and socioeconomic factors but not for age | 8 cases, 73 controls | Median age 7.9 years for cases and 7.4 years for controls |

Association between breast feeding and coeliac disease

Ever breast fed versus never breast fed

There were not enough data in the primary studies to allow comparison of the groups based on this variable.

Duration of breast feeding

The risk of duration of breast feeding on the development of CD was measured in different ways between studies. Greco et al compared children breast fed for at least 90 days with children breast fed for more than 90 days,22 Peters et al compared children breast fed for more than 2 months with those breast fed for less than 2 months,4 and Auricchio et al compared children breast fed for more than 30 days with those breast fed for less than 30 days.5 Falth‐Magnusson et al23 and Ascher et al6 compared the median time of both exclusive and partial breast feeding in cases and controls. Thus because of the use of different ways of assessing the duration of breast feeding, we considered it inappropriate to combine the data on this variable statistically into a single pooled effect. The results of the individual studies are therefore described below.

Greco et al22

Breast feeding rates for cases and controls were similar at birth, but lower for cases by the age of 1 month. From this time onwards, the percentage of children still being breast fed was greater in the control group. Children who were breast fed for less than 90 days were about five times more likely to develop CD compared with children breast fed for more than 90 days (OR 4.97, 95% CI 3.5 to 6.9).

Peters et al4

Compared with controls, children with CD were breast fed (partially and exclusively) for a significantly shorter period. The risk of developing CD decreased significantly by 63% for children breast fed for more than 2 months (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.64) compared with children breast fed for 2 months or less. Using regression analysis to adjust for age, sex, number of inhabitants of residence, and family history of CD, the odds ratio for being breast fed for >2 months compared to being breast fed for ⩽2 months was 0.64 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.95).

What is already known on this topic

Early infant feeding practices may be important risk factors for the development of coeliac disease

Case‐control studies have suggested that breast feeding may reduce the risk of coeliac disease, but the results of the studies have been inconsistent

Falth‐Magnusson et al23

Children with CD were breast fed for a significantly shorter time than controls. The median time of exclusive breast feeding in cases was 2.5 months (range 0–8), and in controls was 4 months (range 0–10) (p = 0.0002). The median time of partial breast feeding was 3.9 months (range 0–12) in cases and 6 months (range 0–33) in controls (p = 0.0001).

Ivarsson et al3

In children less than 2 years old, the median (25th, 75th centile) duration of breast feeding was 5 months (3, 7) for cases, and 7 months (4, 9) for controls (p < 0.001). No significant difference was found between the groups with regard to children older than 2 years.

Auricchio et al5

Increased duration of breast feeding was associated with decreased risk of developing CD. Infants breast fed for less than 30 days were about four times more likely to develop CD compared with infants breast fed for more than 30 days (OR 4.05, 95% CI 2.20 to 7.27).

Ascher et al6

The median duration of breast feeding was 6.5 months (range 1.5–9) in cases and 5.0 (0–14) in controls, but this was not statistically significant.

Breast feeding at the time of gluten introduction

Four of the included studies3,4,6,23 provided enough data on the risk of developing CD in infants who were breast feeding at the time of gluten introduction versus those not being breast fed during this period, to allow a meta‐analysis to be performed on this variable. The total number of participants in these studies was 1969 (714 cases and 1255 controls).

In the main analysis using the fixed effects model (fig 1), the risk of developing CD was significantly reduced in participants who were breast feeding at the time of gluten introduction (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.59). The results of these studies appeared to be reasonably homogeneous and the test for heterogeneity was negative (p = 0.32). The results of the meta‐analysis was practically unchanged when the random effects model was used in a sensitivity analysis (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.62).

Figure 1 Odds ratios (95% CI) of effect of breast feeding at the time of gluten introduction on development of CD.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that breast feeding may offer protection against the development of CD. Meta‐analysis of data of four studies indicated that children being breast fed at the time of gluten introduction had a 52% reduction in risk of developing CD compared with their peers who were not breast feeding at the time of gluten introduction. With the exception of one small study,6 all the studies included in the review also showed a statistically significant association between increasing duration of breast feeding and reduced risk of CD. The sample size of that study was, however, quite small (see table 1), and there was a risk of a type II error. We cannot tell, from the results of the primary studies, whether breast feeding provides a permanent protection against the development of CD or whether the practice only delays the onset of symptoms. All the included studies, except Ascher et al,6 had used healthy children without symptoms of CD as controls without subjecting them to small intestinal biopsies. CD can be notoriously asymptomatic and the absence of symptoms does not necessarily mean absence of the disease.

What this study adds

Breast feeding at the time of gluten introduction significantly reduces the risk of coeliac disease. Increasing duration of breast feeding is associated with a reduced risk of coeliac disease

It is not clear from the primary studies whether breast feeding only delays the onset of symptoms or provides a permanent protection against the disease

The actual mechanism through which breast milk protects against the development of CD is unclear. It could be that continuing breast feeding at the time of weaning limits the amount of gluten that the child receives, thereby decreasing the chances of the child developing symptoms of CD. Ivarsson et al found that children with CD received larger initial amounts of flour compared to controls.3 Another mechanism through which breast milk could protect against CD is by preventing gastrointestinal infections in the infant. Breast milk is known to significantly protect against a number of infections including gastroenteritis.24 Infections of the gastrointestinal tract in early life could lead to increased permeability of the intestinal mucosa, allowing the passage of gluten into the lamina propria. Gut infections are also known to increase tissue transglutaminase expression and this could favour the generation of deamidated gluten peptides,25 triggering CD in susceptible individuals.

Juto et al have suggested two other possible mechanisms by which breast milk could confer protection against CD.26 Firstly, human milk IgA antibodies may diminish immune response to ingested gluten by mechanisms such as agglutination of the antigen to immune complexes on the mucosal surface so that uptake is prevented. Secondly, the immune modulating property of human milk may be exerted through its T‐cell specific suppressive effect as shown by experiments on peripheral lymphocytes stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin, OKT3, and alloantigens.27

Limitations

The results of this study are subject to limitations. The included studies were case‐control studies, which are subject to recall bias. Misclassification of the duration of breast feeding and of the age of introduction of gluten was likely to occur. If, for instance, parents of children with CD could recall more accurately that their children were not breast feeding at the time of gluten introduction, bias could result which would tend to inflate the association in favour of breast feeding.

Case‐control studies are also susceptible to bias because other risk factors of CD could be unbalanced across children who were breast fed and those who were not. While the individual studies tried to control for a number of potential confounding factors such as age, sex, and area of residence, it is likely that a number of other confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status, could have been unbalanced across children who were breast fed and those who were not.

The only study that controlled for HLA genotype did not find a significant difference between the groups with regard to duration of breast feeding but as earlier stated, the sample size of this study of only eight cases was so small that a type II error was likely to have occurred.6

Conclusions

Breast feeding may offer protection against the development of CD. Breast feeding during the introduction of dietary gluten, and increasing duration of breast feeding were associated with decreased risk of developing CD. It is, however, not clear from the primary studies whether breast feeding delays the onset of symptoms or provides a permanent protection against the disease. Long term prospective cohort studies are required to investigate further the relation between breast feeding and CD.

Abbreviations

CD - coeliac disease

CI - confidence interval

OR - odds ratio

RR - relative risk

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Ferenci D A. Celiac disease. In: Altschuler SM, Liacouras CA, eds. Clinical pediatric gastroenterology. Churchill Livingstone 1998143–150.

- 2.Bingley P J, Williams A J, Norcross A J.et al Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Study Team. Undiagnosed coeliac disease at age seven: population based prospective birth cohort study, BMJ 2004328322–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivarsson A, Hernell O, Stenlund H.et al Breast‐feeding protects against celiac disease. Am J Clin Nutr 200275914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters U, Schneeweiss S, Trautwein E A.et al A case‐control study of the effect of infant feeding on celiac disease. Ann Nutr Metab 200145135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auricchio S, Follo D, de Ritis G.et al Does breast feeding protect against the development of clinical symptoms of celiac disease in children? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 19832428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ascher H, Krantz I, Rydberg L.et al Influence of infant feeding and gluten intake on coeliac disease. Arch Dis Child 199776113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Oxford, UK. http://www.phru.nhs.uk/casp/case_control_studies.htm (accessed 10 August 2004)

- 8. Clarke M, Oxman AD, eds. Selecting studies. Cochrane reviewers' handbook 4.2.0 [updated March 2003]. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software, 2003

- 9.Blettner M, Sauerbrei W, Schlehofer B.et al Traditional reviews, meta‐analyses and pooled analyses in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 1999281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy R J, Thompson S G. Detecting and describing heterogeneity in meta‐analysis. Stat Med 199817841–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 19867177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton A J, Duval S J, Tweedie R L.et al Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta‐analyses.BMJ 20003201574–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nash S. Does exclusive breast‐feeding reduce the risk of coeliac disease in children? Br J Community Nurs 20038127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernell O, Ivarsson A, Person L A. Celiac disease: effect of early infant feeding on the incidence of the disease. Early Hum Dev 200165(suppl)S153–S160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persson L A, Ivarsson A, Hernell O. Breast‐feeding protects against celiac disease in childhood—epidemiological evidence. Adv Exp Med Biol 2002503115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matek Z, Jungvirth‐Hegedus M, Kolacek S. Epidemiology of celiac disease in children in one Croatian County: possible factors that could affect the incidence of celiac disease and adherence to a gluten‐free diet. Coll Anthropol 200024397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greco L, Mayer M, Grimaldi M.et al The effect of early feeding on the onset of symptoms in celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1985452–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cataldo F, Maltese I, Paternostro D.et al Celiac disease and dietary habits in the 1st year of life. Minerva Pediatr 1991437–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouguerra F, Hajjem S, Guilloud‐Bataille M.et al Breast feeding effect relative to age of onset of celiac disease. Arch Pediatr 19985621–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Challacombe D N, Mecrow I K, Elliott K.et al Changing infant feeding practices and declining incidence of coeliac disease in West Somerset. Arch Dis Child 199777206–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson C M, Brueton M J. Does breast feeding protect against development of clinical symptoms of celiac disease in children? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 19854507–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greco L, Auricchio S, Mayer M.et al Case control study on nutritional risk factors in celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 19887395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falth‐Magnusson K, Franzen L, Jansson G.et al Infant feeding history shows distinct differences between Swedish celiac and reference children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 199671–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanson L A, Korotkova M, Haversen L.et al Breast‐feeding, a complex support system for the offspring. Pediatr Int 200244347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sollid L M. Breastmilk against coeliac disease. Gut 200251767–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juto P, Meeuwisse G, Mincheva‐Nilsson L. Why has coeliac disease increased in Swedish children? Lancet 19943431372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mincheva‐Nilsson L, Hammarstrom M L, Juto P.et al Human milk contains proteins that stimulate and suppress T lymphocyte proliferation. Clin Exp Immunol 199079463–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]