Abstract

Background

Routine influenza vaccination for children aged 6–23 months has recently been recommended in the United States. Accurate assessment of influenza related burden of illness in children could support similar recommendations in other settings. However, routinely available data underestimate the role of influenza in causing hospitalisation, and indirect estimation methods face difficulties controlling for the concurrent circulation of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Recent studies from Hong Kong and the United States have used differing methods to estimate the true burden of influenza related hospitalisation, with disparate results.

Methods

Retrospective population based study of children less than 18 years of age from Sydney, Australia, 1994 to 2001. Using two previously reported methods, estimates of annual hospitalisation rates attributable to influenza were derived by comparison of mean hospitalisation rates for acute respiratory disease during periods of high influenza activity and low RSV activity (defined using virological surveillance data) and periods where both influenza and RSV activity were low. These estimates were compared to rates of hospitalisation where influenza was recorded as the principal discharge diagnosis.

Results

Hospitalisation rates attributable to influenza were up to 11 times higher, depending on the age group and method used, compared to rates calculated from principal discharge diagnosis codes.

Conclusions

Although there remains considerable uncertainty in estimating influenza related morbidity by methods using excess hospitalisations, even minimum estimates of disease burden warrant consideration of routine influenza immunisation for all children less than 2 years of age. Such estimates, derived from principal discharge diagnosis codes, are available in most settings.

Keywords: influenza, hospitalisation

High rates of hospitalisation have been recognised in young children during influenza seasons for decades.1 It has however been difficult to separate the contribution of influenza from other respiratory viruses, particularly respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). RSV is thought to be the principal cause of lower respiratory disease in young children2,3 and often circulates concurrently with influenza viruses. However, influenza may contribute more to the burden of respiratory disease than is indicated by routinely available data. Underestimation may result from variation in diagnostic practices, such as the extent of virological testing and the coding of principal hospital discharge diagnoses as due to secondary bacterial infection or exacerbation of chronic medical conditions. As the impact of influenza varies considerably from year to year, depending on herd immunity and the virulence of circulating strains, disease burden must be measured over a number of years.4

Recent studies in the United States2,3,4 and Hong Kong5 have used differing methods to estimate the burden of hospitalisation for acute respiratory disease2,5 and acute cardiopulmonary conditions3,4 attributable to influenza in children. These studies present disparate findings but all conclude that significant morbidity can be attributed to influenza virus, even in healthy young children. This has stimulated debate over the potential economic benefits across all ages of universal immunisation of young children.2,3,6,7 The Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practice in the United States has recently recommended routine influenza vaccination, requiring two doses of the current inactivated vaccine, for all children aged 6–23 months.8 Delivery of two additional annual injections is likely to create substantial logistic difficulties. However, the recent advent of an effective and well tolerated intranasal influenza vaccine9,10 could enhance the feasibility and acceptability of such an intervention, if the vaccine is licensed for younger age groups and becomes more widely available at an acceptable cost. Advisory bodies in countries other than the USA will require locally applicable data on influenza burden to inform their recommendations, as influenza burden in populations is influenced by climate, age structure, and prevalence of co‐morbidities.2,3,4,5

Data on influenza burden in Australian children are limited to those routinely available from hospital discharge coding data sets.11,12 Internationally, published data from application of indirect estimation methods have been limited to Hong Kong and the United States.2,3,4,5 Our study had two objectives. First, to apply the methods used in published studies elsewhere2,5 to Australian data to estimate the burden of influenza related hospitalisations in young children. Second, we wished to compare these estimates with each other and those similarly derived in the United States and Hong Kong, as well as with Australian data for hospitalisations coded with influenza as the principal diagnosis, in order to determine the most feasible and appropriate methods for routine application in other settings.

Methods

Data sources

We used existing sources of data on hospitalisations and laboratory identified viral isolates to construct retrospective population based data sets, limited by age and area of residence, in order to calculate rates of hospitalisation for acute respiratory disease attributable to influenza.

Hospitalisation data were obtained from the New South Wales (NSW) Inpatient Statistics Data Collection. This collection contains information on all hospital admissions, to both public and private hospitals, in NSW, Australia, since mid‐1993. We accessed these data via HOIST (Health Outcomes Indicator Statistical Toolbox), a NSW Department of Health population data access and analysis facility.13 We obtained de‐identified data on children aged less than 18 years, resident in the Sydney Statistical Division, with a discharge diagnosis of acute respiratory disease (codes 460–496 or 510–519 of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) or, using forward mapping tables from the National Centre for Classification in Health, Australia, equivalent codes of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Australian Modification (ICD‐10‐AM)). Australian Bureau of Statistics mid‐year estimates for the Sydney Statistical Division were used to define the population at risk and to calculate incidence rates.

We obtained virological surveillance data from the Laboratory Virology and Serology Reporting Scheme, a passive surveillance scheme based on voluntary reports by laboratories around Australia.14 De‐identified data were obtained relating to reports between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 2001 of influenza virus, RSV, and parainfluenza virus in children less than 18 years of age and resident in the Sydney Statistical Division, from all major laboratories that processed specimens from hospitalised children in Sydney and reported over this period. Using these data we conducted an exploratory analysis of seasonal patterns by year and virus to identify suitable study periods (see below).

Study methods

Study period

The methods used in a published study from Hong Kong5 (our Method 1) were applied to a single year (2000) only, as this was the only year with relatively distinct separation of the influenza and RSV seasons, a requirement for this method to be effective.5 The methods used in a published study from the United States2 (our Method 2) were able to be applied to the entire study period (1994–2001). Minor modifications to the methods presented in the original reports were made, as described below.

Estimating influenza related hospitalisations

Methods 1 and 2

Both Methods 1 and 2 required a comparison between the weekly hospitalisation rates for acute respiratory disease during periods of high influenza activity and low RSV activity (influenza predominant periods) with rates during periods where both influenza and RSV activity were low (baseline periods).2,5 We calculated mean weekly hospitalisation rates per 100 000 population by age group for each comparison period as the number of cases divided by the number of weeks in the period, multiplied by 100 000 and divided by the population at risk. We subtracted baseline rates from influenza predominant period rates to determine excess weekly rates attributable to influenza. We then derived annual rates of hospitalisation attributable to influenza by multiplying excess weekly rates by the number of weeks during the influenza predominant period; 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the normal approximation to the Poisson distribution.

Method 3

For Method 3, hospitalisations where influenza was recorded as the principal discharge diagnosis were identified for both 2000 and the entire study period.

We calculated annual hospitalisation rates per 100 000 population by age group.

Comparison periods

Method 15

The period in which influenza predominated was defined as all periods of two or more consecutive weeks in which at least 4% of annual cases of virologically confirmed influenza and less than 2% of annual cases of virologically confirmed RSV were recorded. The baseline period was defined as all periods of two or more consecutive weeks in which both influenza and RSV diagnoses were less than or equal to 1% of their annual totals. The figure of 1% was chosen, rather than 2% as in the original Hong Kong study,5 because the more pronounced seasonal variation in Sydney allows this more rigorous definition.

Method 22

The period in which influenza predominated was defined as all periods of two or more consecutive weeks, between April and November (modified from between October and May in the original American study2 due to our Southern Hemisphere setting), in which at least 5% of annual cases of virologically confirmed influenza were recorded and less than 5% of annual cases of RSV were recorded. The periseasonal baseline period was defined as all periods of two or more consecutive weeks, between April and November, in which both influenza and RSV diagnoses were less than 5% of the annual total and in which no isolates of parainfluenza virus were detected. While the original study defined the summer baseline period as all two week periods with no isolates of influenza, RSV, or parainfluenza,2 sporadic isolates throughout summer in our surveillance data reduced the utility of this definition. We therefore defined the summer baseline period as the first four weeks of each year, this period having consistently low viral activity across all study years. For each period defined above, all such weeks during the entire study period were combined for analysis.

Method 3

No comparison periods were required—all weeks in the relevant year or years were combined as the study period.

Eligible hospital discharge codes

Method 15

Hospitalisations for acute respiratory disease in which ICD‐9‐CM codes 460–466 or 480–487 (or equivalent ICD‐10‐AM codes) were listed as one of the discharge diagnoses, as in the original Hong Kong study.5

Method 22

Hospitalisations for acute respiratory disease in which ICD‐9‐CM codes 460–496 or 510–519 (or equivalent ICD‐10‐AM codes) were listed as one of the discharge diagnoses, as in the original American study.2

Method 3

Hospitalisations in which influenza (ICD‐9‐CM code 487 or ICD‐10‐AM codes J10 and J11) was listed as the principal discharge diagnosis.

Comparison with other studies

In order to compare our findings with those from previous studies,2,5 we recalculated the annual rates of hospitalisation attributable to influenza for specific age groups using the data presented in the studies and the analytical methods described for our Methods 1 and 2.

Results

Comparison periods

Method 1

In 2000 there were seven weeks in which the circulation of influenza predominated relative to that of RSV. There were 15 weeks when both influenza and RSV activity was low (baseline period).

Method 2

During the entire study period from 1994 to 2001 there were 27 weeks during which the circulation of influenza predominated relative to that of RSV. In individual years the period during which the circulation of influenza predominated varied from zero (1995 and 1999) to five (1994, 1997, and 1998) weeks. Between 1994 and 2001, there were 21 weeks from April to November when both influenza and RSV activity were low (periseasonal baseline period). During individual years the periseasonal baseline period varied from zero (1996 and 1999) to six (2000) weeks. By definition, the summer baseline period was 32 weeks.

Influenza related hospitalisation rates

Method 1

Weekly hospitalisation rates for acute respiratory disease among Sydney children in 2000 during periods in which influenza predominated and during baseline periods are shown in table 1, along with derived annual rates of hospitalisation attributable to influenza.

Table 1 Rates of hospitalisation for acute respiratory disease in Sydney children under 18 years of age, 2000, by age and study period, using Method 1*.

| Age group | Population at risk† | Number of hospitalisations | Mean weekly rate | Annual rate attributable to influenza (95% CI)‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate/100 000 population‡ | |||||||

| Influenza predominant period | Baseline period | Influenza predominant period | Baseline period | Excess attributable to influenza | |||

| <1 y | 55972 | 558 | 482 | 142 | 56 | 86 | 604 (514 to 694) |

| 1 to <2 y | 54566 | 443 | 459 | 116 | 55 | 61 | 424 (340 to 507) |

| 2 to <5 y | 161989 | 519 | 676 | 46 | 27 | 18 | 128 (97 to 159) |

| 5 to <10 y | 268358 | 217 | 261 | 12 | 6 | 5 | 36 (24 to 48) |

| 10 to <18 y | 417458 | 150 | 230 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 10 (4 to 17) |

*As per previous study.5

†Australian Bureau of Statistics mid‐year estimate for 2000.

‡Rates and CIs rounded to whole numbers.

Method 2

Weekly hospitalisation rates for acute respiratory disease among Sydney children during periods in which influenza predominated and during baseline periods from 1994 to 2001 are shown in table 2 (summer baseline) and table 3 (periseasonal baseline), along with derived annual rates of hospitalisation attributable to influenza.

Table 2 Rates of hospitalisation for acute respiratory disease, Sydney children under 18 years of age, 1994–2001, by age and study period, using Method 2 with summer baseline*.

| Age group | Population at risk† | Number of hospitalisations | Mean weekly rate | Annual rate attributable to influenza (95% CI)‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate/100 000 population‡ | |||||||

| Influenza predominant period | Baseline period | Influenza predominant period | Baseline period | Excess attributable to influenza | |||

| <1 y | 55972 | 3015 | 1059 | 206 | 61 | 145 | 489 (473 to 504) |

| 1 to <2 y | 54566 | 2538 | 1046 | 171 | 60 | 112 | 377 (363 to 391) |

| 2 to <5 y | 161989 | 4427 | 2430 | 102 | 47 | 55 | 184 (165 to 203) |

| 5 to <10 y | 268358 | 3197 | 2419 | 45 | 28 | 16 | 54 (37 to 72) |

| 10 to <18 y | 417458 | 2840 | 2651 | 25 | 20 | 5 | 18 (1 to 35) |

*As per previous study.2

†Australian Bureau of Statistics mid‐year estimate for 1998.

‡Rates and CIs rounded to whole numbers.

Table 3 Rates of hospitalisation for acute respiratory disease, Sydney children under 18 years of age, 1994–2001, by age and study period, using Method 2 with periseasonal baseline*.

| Age group | Population at risk† | Number of hospitalisations | Mean weekly rate | Annual rate attributable to influenza (95% CI)‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate/100 000 population‡ | |||||||

| Influenza predominant period | Baseline period | Influenza predominant period | Baseline period | Excess attributable to influenza | |||

| <1 y | 55972 | 3015 | 1829 | 206 | 160 | 45 | 153 (126 to 180) |

| 1 to <2 y | 54566 | 2538 | 1660 | 171 | 144 | 27 | 92 (73 to 111) |

| 2 to <5 y | 161989 | 4427 | 3342 | 102 | 99 | 3 | 10 (0 to 26) |

| 5 to <10 y | 268358 | 3197 | 2514 | 45 | 45 | 0 | 2 (0 to 12) |

| 10 to <18 y | 417458 | 2840 | 2051 | 25 | 23 | 2 | 6 (0 to 19) |

*As per previous study.2

†Australian Bureau of Statistics mid‐year estimate for 1998.

‡Rates and CIs rounded to whole numbers.

Method 3

Hospitalisation rates where influenza was coded as the principal discharge diagnosis are included in table 4. From mid‐1997, when the introduction of ICD‐10‐AM codes permitted differentiation by virological confirmation status, 82% of hospitalisations overall (and 90% of those in children under 2 years of age) where influenza was coded as the principal discharge diagnosis were recorded as virologically confirmed.

Table 4 Rates of annual hospitalisation attributable to influenza by age, Sydney children under 18 years, using different methods*.

| Age group | Annual rate/100 000 persons† (95% CI)‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 1994–2001 | ||||

| Method 1 | Method 3 | Method 2§ | Method 2¶ | Method 3 | |

| <1 y | 604 (514 to 694) | 177 (173 to 180) | 489 (473 to 504) | 153 (126 to 180) | 96 (95 to 96) |

| 1 to <2 y | 424 (340 to 507) | 64 (61 to 68) | 377 (363 to 391) | 92 (73 to 111) | 44 (44 to 45) |

| 2 to <5 y | 128 (97 to 159) | 17 (15 to 18) | 184 (165 to 203) | 10 (0 to 26) | 16 (16 to 16) |

| 5 to <10 y | 36 (24 to 48) | 4 (3 to 5) | 54 (37 to 72) | 2 (0 to 12) | 5 (4 to 5) |

| 10 to <18 y | 10 (4 to 17) | 5 (4 to 5) | 18 (1 to 35) | 6 (0 to 19) | 2 (2 to 3) |

What is already known on this topic

Routine influenza vaccination for children aged 6–23 months has been recently recommended in the United States

Accurate assessment of influenza related burden of illness in children is lacking in many other settings

All methods combined

Annual rates of hospitalisation among Sydney children attributable to influenza are shown in table 4 for each of our study methods. Rates were consistently highest in the youngest age groups and progressively decreased with increasing age. Estimated rates of excess hospitalisation for acute respiratory disease attributable to influenza (Methods 1 and 2) were generally higher than the rates of hospitalisation calculated where influenza was coded as the principal discharge diagnosis (Method 3). Depending on the method used, they were 2–9 times higher for children under 1 year of age; 2–7 times higher for children 1–2 years of age; and up to 11 times higher for older age groups.

Comparison with previous findings

Annual rates of hospitalisation attributable to influenza, for our study and selected previous studies, are presented in table 5.

Table 5 Rates of excess hospitalisation attributable to influenza by age group, from selected studies.

| Study site | Study period | Annual rate/100 000 persons (95% CI)† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <2 y | 2 to <5 y | 5 to 16 or 18 y* | ||

| Sydney | 2000 | 515 (454 to 577) | 128 (97 to 159) | 21 (14 to 27) |

| 1994–2001‡ | 432 (412 to 453) | 184 (165 to 203) | 32 (8 to 56) | |

| 1994–2001§ | 122 (96 to 148) | 10 (0 to 35) | 3 (0 to 32) | |

| California2 | 1993–1997‡ | 113 (85 to 141) | 19 (7 to 32) | 0 (0 to 4) |

| 1993–1997§ | 84 (55 to 113) | 12 (0 to 24) | 4 (0 to 8) | |

| Seattle2 | 1992–1997‡ | 140 (91 to 190) | 6 (0 to 22) | 5 (0 to 11) |

| 1992–1997§ | 95 (43 to 147) | 0 (0 to 15) | 7 (2 to 13) | |

| Hong Kong5 | 1998 | 630 (620 to 639) | 322 (318 to 326) | 92 (91 to 93) |

| 1999 | 1065 (1055 to 1076) | 336 (332 to 340) | 62 (61 to 63) | |

*To <18 y (Sydney, California, Seattle) or <16 y (Hong Kong).

†Rates and CIs rounded to whole numbers.

‡Using summer baseline.

§Using periseasonal baseline.

Discussion

As with previous studies, we found rates of hospitalisation attributable to influenza were consistently highest in young children and progressively decreased to age 18 years. Our methods for estimating excess hospitalisation produced annual rates attributable to influenza in children that were, depending on the method and age group, between 2 and 11 times higher than the rate calculated from hospitalisations where influenza was coded as the principal discharge diagnosis. The latter would be expected to be a minimum estimate of disease burden. While Method 1 produced the highest estimates overall, it relied on data from a single year (2000) in which hospitalisation rates where influenza was coded as the principal discharge diagnosis were considerably higher in children under 2 years of age, compared to the average for the entire study period.

Our estimates of hospitalisation for acute respiratory disease attributable to influenza were appreciably lower than estimates from Hong Kong,5 but higher than those from a previous United States study.2 These United States estimates excluded children with high risk underlying conditions and are therefore not directly comparable to our own. Previous studies have found 3–10% of children to be at increased risk,2,4,5 with the relative risk (RR) of hospitalisation for acute respiratory disease in high risk children being lower in children under 2 years of age (RR = 4–5) than in children 2 years of age or older (RR = 13–21).2 This could explain some of the differences between our rates and those from the United States. Some of the differences between our results and those from other studies may also be due to actual variation in incidence between countries and over time.

However, there is considerable uncertainty as to whether influenza can be held responsible for all, or even most, of the morbidity attributed to it by the various methods used to estimate excess hospitalisations due to influenza. The methods used in the American study,2 on which our Method 2 is based, may not be very effective at accounting for confounding by RSV.6 As RSV is known to be responsible for a large number of hospitalisations for acute respiratory disease in children under 2 years of age,15 influenza predominant periods defined by relative levels of activity could still contain higher levels of RSV activity in absolute terms. The methods used in the Hong Kong study5 on which our Method 1 is based, are preferable where influenza and RSV seasons are separate. However, while the Hong Kong study found a strong temporal correlation between virologically confirmed influenza activity and peaks in hospitalisation for acute respiratory disease,5 this correlation was not as marked for the single year analysed in our study. We are therefore less able to exclude confounding effects of other respiratory viruses such as RSV or annual variations in environmental factors such as temperature and humidity. More sophisticated modelling, for example accounting for environmental variables through time series analyses, may be useful to explore these issues.

What this study adds

Even minimum estimates of influenza disease burden in Australia warrant consideration of routine influenza immunisation for all children aged 6–23 months

Routinely available data may be sufficient to inform local recommendations on influenza immunisation in many settings

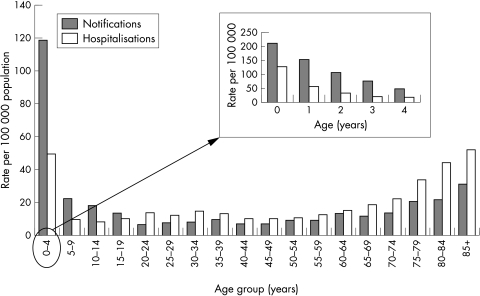

Our study is however useful in that it quantifies the differences between estimates of influenza related burden of illness produced by existing and relatively straightforward methods. While the estimates using excess hospitalisation methods could overestimate disease burden, even the minimum estimates of influenza disease burden derived from principal discharge diagnoses of influenza are substantial and warrant consideration of routine influenza immunisation for all children under 2 years of age. Influenza related morbidity in older people is more widely recognised and has driven routine annual vaccination recommendations in most industrialised countries, including the United Kingdom. However, rates of hospitalisation for influenza are higher in young children than in the elderly in Australia (fig 1), although median length of stay per admission and death rates recorded as due to influenza are lower—half and one tenth respectively for children under 5 years of age compared to adults over 60.12 Data such as those presented here for children are routinely available in many settings and may be sufficient to inform local recommendations on influenza immunisation. Intensive use of virological analyses in all children hospitalised with acute respiratory disease would improve the accuracy of these routinely available data.

Figure 1 Influenza notification rates 2002 and hospitalisation rates 2000–02, Australia, by age group.12 (Notifications of laboratory confirmed infections in which influenza virus isolated by cell culture, detected by nucleic acid testing, by influenza antigen testing, or by serological methods. Hospitalisations where date of separation between 1 July 2000 and 30 June 2002 and influenza (ICD‐10‐AM codes J10 and J11) recorded as one of the discharge codes.)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Andrew Hayen for statistical advice, Dr Alison Kesson for provision of data, and Dr Julia Brotherton for comments on the final drafts of this paper. NCIRS is supported by The Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, The New South Wales Department of Health, and The Children's Hospital at Westmead.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none

References

- 1.Glezen P, Denny F W. Epidemiology of acute lower respiratory disease in children. N Engl J Med 1973288498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Izurieta H S, Thompson W W, Kramarz P.et al Influenza and the rates of hospitalization for respiratory disease among infants and young children. N Engl J Med 2000342232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuzil K M, Zhu Y, Griffin M R.et al Burden of interpandemic influenza in children younger than 5 years: a 25‐year prospective study. J Infect Dis 2002185147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuzil K M, Mellen B G, Wright P F.et al The effect of influenza on hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and courses of antibiotics in children. N Engl J Med 2000342225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu S S, Lau Y L, Chan K H.et al Influenza‐related hospitalizations among children in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 20023472097–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McIntosh K, Lieu T. Is it time to give influenza vaccine to healthy infants? N Engl J Med 2000342275–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abramson J S, Baker C J, Baltimore R S.et al Reduction of the influenza burden in children. Pediatrics 20021101246–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper S A, Fukuda K, Uyeki T M.et al Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004531–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belshe R B, Gruber R C. Safety, efficacy, and effectiveness of cold‐adapted, live, attenuated, trivalent, intranasal influenza vaccine in adults and children. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 20013561947–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradshaw J, Wright P F. Cold‐adapted influenza vaccines. Curr Opin Pediatr 20021495–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIntyre P, Gidding H, Gilmour R.et al Vaccine preventable diseases and vaccination coverage in Australia, 1999–2000. Commun Dis Intell 200226S1–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brotherton J, McIntyre P, Puech M.et al Vaccine preventable diseases and vaccination coverage in Australia, 2001–2002. Commun Dis Intell 200428S1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centre for Epidemiology and Research, Population Health Division, New South Wales Department of Health Health Outcomes Information Statistical Toolkit (HOIST). http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/public‐health/epi/hoist.html [accessed 5 June 2004]

- 14.Roche P, Halliday L, O'Brien E.et al The Laboratory Virology and Serology Reporting Scheme, 1991 to 2000. Commun Dis Intell 200226323–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher R G, Gruber W C, Edwards K M.et al Twenty years of outpatient respiratory syncytial virus infection: a framework for vaccine efficacy trials. Pediatrics 199799e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]