Short abstract

Commentary on the papers by Williams et al (see page 8) and Harrison et al (see page 16)

Keywords: autism, assortative mating

The autistic spectrum comprises four subgroups: Asperger's syndrome (AS),1,2 and high, medium, and low functioning autism.3 They all share the phenotype of social difficulties and obsessional interests.4 In AS, the individual has normal or above average IQ and no language delay. In the three autism subgroups there is invariably some degree of language delay, and the level of functioning is indexed by overall IQ. These four subgroups are known as autism spectrum conditions (ASC).

Williams and colleagues5 searched electronic databases and bibliographies to carry out a meta‐analysis of 42 studies of prevalence of autism spectrum conditions (ASC). From this, their most generous estimate was 20 per 10 000, or 0.2%. Harrison and colleagues6 used the “capture–recapture” technique in Lothian, Scotland, and their prevalence estimate was 44.2 per 10 000, or 0.44%. This corresponds to 1 child in 225. These estimates are clearly much higher than was the case in the past, where prevalence was traditionally estimated to be 4 in 10 000.

Beyond counting and prevalence estimates

Now we know that ASC are common. How should we understand their causes? Harrison and colleagues6 find that the 13–15 year old age group who would have received their MMR during the data collection phase were actually less numerous than the 4–10 year old age group, suggesting this high rate cannot be due to the MMR vaccine (since both age groups were exposed to the MMR). Instead they argue that these data suggest better recognition, better recording of cases, and growth of services.

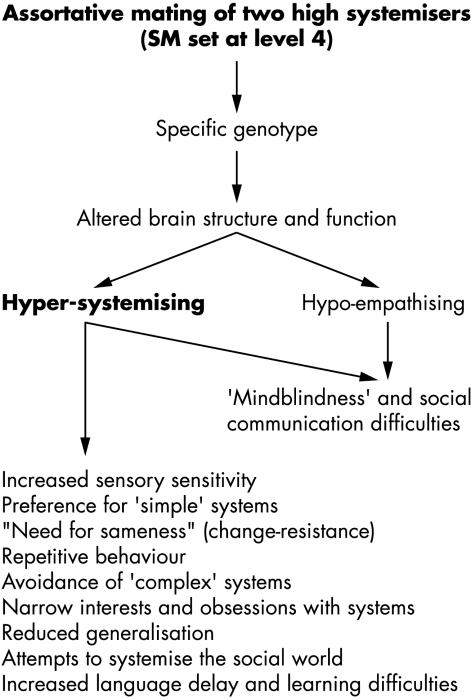

In terms of causes, the consensus is that ASC have a genetic aetiology,7 which leads to altered brain development,8,9,10,11 affecting social and communication development and leading to the presence of unusual narrow interests and extreme repetitive behaviour.4 The model we can use involves multiple levels (see fig 1). In what follows I will elaborate on the two new ideas, shown in bold in the model.

Figure 1 Multi‐level model of autism spectrum conditions.

Hyper‐systemising

A universal feature in the environment that the brain has to react to is change. There are two types of structured change:

Agentive change: If an object change is perceived to be self‐propelled, the brain interprets the object as an agent, with a goal.12,13 Such change cannot easily be predicted in any other way. To interpret agentive change, humans have specialised neurocognitive mechanisms, collectively referred to as the “empathising system”.14,15,16 The neural circuitry of empathising is now quite well mapped.9,10,11 Key brain areas involved in empathising include the amygdala, the orbito and medial frontal cortex, and the superior temporal sulcus.

Non‐agentive change: Any structured change that is not self‐propelled is interpreted by the brain as a non‐agentive change. “Structured” means non‐random, for example that there is a precipitating event, or some other pattern. The brain doe not deploy the empathising mechanisms to predict such change. Instead, the human brain engages in “systemising”, that is, it searches for structure (patterns, rules, regularities, periodicity) in data, to test if the changing data are part of a system. Systemising involves observation of input–operation–output relationships, leading to the identification of laws to predict that event x will occur with probability p.17

Some systems are 100% lawful (for example, an electrical light switch, or a mathematical formula) (see table 1). Systems that are 100% lawful have zero variance, or only 1 degree of freedom, and can therefore be predicted (and controlled) 100%. A computer might be an example of a 90% lawful system: the variance is wider or there are more degrees of freedom. Growing hydrangeas may be a system with 80% lawfulness (see table 2). The social world may be only 10% lawful. This is why systemising the social world is of little predictive value.

Table 1 Two examples of 100% lawful systems: (a) An electricity switch, and (b) a mathematical rule.

| Input | Operation and output |

|---|---|

| Input = switch position | Operation = switch change |

| Output = light | |

| Up | On |

| Down | Off |

| Input = number | Operation = add 2 |

| Output = number | |

| 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 5 |

| 4 | 6 |

Table 2 An example of systemising hydrangea colour.

| Operation (type of soil) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic | Neutral | Alkaline | |

| Input (type of hydrangea) | Output (colour of hydrangea) | ||

| Annabelle | White | White | White |

| Blauer prinz | Blue | Purple | Purple |

| Bouquet rose | Blue | Purple | Pink |

| Deutschland | Purple | Red | Red |

| Enziandom | Blue | Purple | Red |

From http://www.hydrangeasplus.com.

Systemising involves recording input and output and deriving the rules how an operation changes the output.

Systemising involves five phases:

Phase 1 = Analysis: Single observations of input (for example, hydrangea type) and output (colour) are recorded in a standardised manner at the lowest level of detail.

Phase 2 = Operation: An operation is performed on the input and the change to the output is noted.

Phase 3 = Repetition: The same operation is repeated over and over again to test if the same pattern between input and output is obtained.

Phase 4 = Law derivation: A law is formulated of the form If X (operation) occurs, A (input) changes to B.

Phase 5 = Confirmation/disconfirmation: If the same pattern of input–operation–output holds true for all instances, the law is retained.

If a single instance does not fit the law, phases 2–5 are repeated, leading to modification of the law, or a new law.

Systemising non‐agentive changes is effective because these are simple changes: the systems are at least moderately lawful, with narrow variance (or limited degrees of freedom). Agentive change is less suited to systemising because the changes in the system are complex (wide variance, or many degrees of freedom).

The systemising mechanism (SM)

The hyper‐systemising theory of ASC posits that human brains have a systemising mechanism (SM), and this is set at different levels in different individuals. In people with ASC, the SM is set too high. The SM is like a volume control. Evidence suggests that within the general population, there are eight degrees of systemising:

Level 1: Such individuals have little or no drive to systemise, and consequently they can cope with rapid, unlawful change. Their SM is set so low that that they hardly notice if the input is structured or not. While this would not interfere with their ability to socialise, it would lead to a lack of precision over detail when dealing with structured information. We can think of this as hypo‐systemising. Such a person would be able to cope with agentive change easily, but may be challenged when dealing with highly lawful non‐agentive systems.

Levels 2 and 3: Most people have some interest in lawful non‐agentive systems, and there are sex differences in this. More females in the general population have the SM set at Level 2, and more males have it set at Level 3. For example, on tests of map reading or mental rotation or mechanics, or on the systemising quotient, males perform higher than females.16,18,19,20

Level 4: Level 4 corresponds to individuals who systemise at a higher level than average. There is some evidence that above‐average systemisers have more autistic traits. Thus, scientists (who by definition have the SM set above average) score higher than non‐scientists on the autism spectrum quotient (AQ). Mathematicians score highest of all scientists on the AQ.21 Parents of children with ASC also have their SM set higher than average22,23 and have been described as having the “broader phenotype” of autism. At Level 4 one would expect a person to be talented at understanding systems with moderate variance or lawfulness.

Level 5: People with AS have their SM set at Level 5: the person can easily systemise lawful systems such as calendars or train timetables.24 Experimental evidence for hyper‐systemising in AS includes the following: (i) people with AS score higher than average on the systemising quotient (SQ);19 (ii) people with AS perform at a normal or high level on tests of intuitive physics or geometric analysis;20,25,26,27 (iii) people with AS can achieve extremely high levels in domains such as mathematics, physics, or computer science;28 and (iv) people with AS have an “exact mind” when it comes to art29 and show superior attention to detail.30,31

Levels 6–8: In people with high functioning autism (HFA), the SM is set at Level 6, in those with medium functioning autism (MFA) it is at Level 7, and in low functioning autism (LFA) it is at the maximum setting (Level 8). Thus, people with HFA try to socialise or empathise by “hacking” (that is, systemising),32 and on the picture sequencing task, they perform above average on sequences that contain temporal or physical‐causal information.33 People with MFA perform above average on the false photograph task.34 In LFA, their obsessions cluster in the domain of systems, such as watching electric fans go round;35 and given a set of coloured counters, they show extreme “pattern imposition”.36 Box 1 lists 16 behaviours that would be expected if an individual had their SM turned up to the maximum setting of Level 8.

Unexpected consequences of hyper‐systemising

The hyper‐systemising theory can also explain why some people with autism may have more or less language, or a higher or lower IQ, or differing degrees of mind blindness.14 According to the theory, turning the SM downwards from the maximum level of 8, at each point on the dial the individual should be able to tolerate an increasing amount of change or variance in the system. Thus, if the SM is set at Level 7, the person will be able to deal with systems that are less than 100% lawful, but still highly lawful. The child could achieve a slightly higher IQ (since there is a little more possibility for learning about systems that are less than 100% lawful), and the child would have a little more ability to generalise than someone with classic autism. The higher the level of the SM, the less generalisation,37 since systemising involves identifying laws that might only apply to the current system under observation.

At Level 7, one would expect some language delay, but this might only be a moderate (since someone whose SM is set at Level 7 can tolerate a little variance in the way language is spoken and still see meaningful patterns). And the child's mindblindness would be less than total. If the SM is set at Level 6, such an individual would be able to deal with systems that were slightly less lawful. This would therefore be expressed as only mild language delay, mild obsessions, mild delay in theory of mind, and stilted social behaviour, such as attempts at systemising social behaviour.

The assortative mating of two high systemisers

The evidence for systemising being part of the phenotype for ASC includes the following: fathers and grandfathers of children with ASC are twice as likely to work in the occupation of engineering (a clear example of a systemising occupation), compared to men in the general population.39 The implication is that these fathers and grandfathers have their SM set higher than average (Level 4). Students in the natural sciences (engineering, mathematics, physics) have a higher number of relatives with autism than do students in the humanities.40 Mathematicians have a higher rate of AS compared to the general population, and so do their siblings.41

The evidence that autism could be the genetic result of having two high systemisers as parents (assortative mating) includes the following: (a) both mothers and fathers of children with AS have been found to be strong in systemising on the Embedded Figures Test;22 (b) both mothers and fathers of children with autism or AS have increased rates of systemising occupations among their fathers;39 and (c) both mothers and fathers of children with autism show hyper‐masculinised patterns of brain activity during a systemising task.42 Whether the current high rates of ASC simply reflect better recognition, growth of services, and widening of diagnostic categories to include AS, or also reflect the increased likelihood of two high‐systemisers have children, is a question for future research.

Conclusions

The core of autism spectrum conditions (ASC) is both a social deficit and what Kanner astutely observed and aptly named “need for sameness”.3 According to the hyper‐systemising theory, ASC is the result of a normative systemising mechanism (SM)—the function of which is to serve as a change predicting mechanism—being set too high. This theory explains why people with autism prefer either no change, or appear “change resistant”. It also explains their preference for systems that change in highly lawful or predictable ways (such as mathematics, repetition, objects that spin, routine, music, machines, collections). Finally, it also explains why they become disabled when faced with systems characterised by “complex” or less lawful change (such as social behaviour, conversation, people's emotions, or fiction), since these cannot be easily systemised.

While ASCs are disabling in the social world, hyper‐systemising can lead to talent in areas that are systemisable. For many people with ASC, their hyper‐systemising never moves beyond phase 1 (massive collection of facts and observations—lists of trains and their departure times, watching the spin‐cycle of a washing machine), or phases 2 and 3 (massive repetition of behaviour—spinning a plate or the wheels of a toy car). But for those who go beyond phase 3 to identify a law or a pattern in the data (phases 4 and 5), this can constitute original insight. In this sense, it is likely that the genes for increased systemising have made remarkable contributions to human history.43,44,45

Box 1: Systemising mechanism at Level 8: classic, low‐functioning autism

Key behaviours that follow from extreme systemising include:

Highly repetitive behaviour (e.g. producing a sequence of actions, sounds, or set phrases, or bouncing on a trampoline)

Self‐stimulation (e.g. a sequence of repetitive body‐rocking, finger‐flapping in a highly stereotyped manner, spinning oneself round and round)

Repetitive events (e.g. spinning objects round and round, watching the cycles of the washing machine; spinning the wheels of a toy car)

Preoccupation with fixed patterns or structure (e.g. lining things up in a strict sequence, electrical light switches being in either an ON or OFF position throughout the house)

Prolonged fascination with systemisable change (e.g. sand falling through one's fingers, light reflecting off a glass surface, playing the same video over and over again)

Tantrums at change: as a means to return to predictable, systemisable input

Need for sameness: to impose lack of change onto their world, to turn their world into a totally predictable environment, to make it systemisable

Social withdrawal: since the social world is largely unsystemisable

Narrow interests: in systems (e.g. types of planes)

Mind blindness: since the social world is largely unsystemisable

Attention to detail: the SM records each data point in case it is a relevant variable in a system

Reduced generalisation: hyper‐systemising means a reluctance to formulate a law until there has been sufficient data collection. This could also reduce IQ and breadth of knowledge

Language delay: since other people's spoken language varies every time it is heard, so it is hard to systemise

Islets of ability: channelling attention into the minute detail of one lawful system (e.g. the script of a video, or prime numbers)

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the support of the MRC and the Nancy Lurie‐Marks Family Foundation during this work.

Footnotes

* High functioning autism (HFA) can be thought as within one standard deviation of population mean IQ (that is, IQ of 85 or above); medium functioning autism (MFA) can be thought of as between one and three standard deviations below the population mean (that is, IQ of 55–84). Low functioning autism (LFA) can be thought of below this (that is, IQ of 54 or below).

† This may help to explain why videos like Thomas the Tank Engine are favourites for many children with autism: there is no agentive change and almost all the non‐agentive change is mechanical and linear, with close to 100% lawfulness.

† † I am indebted to Nigel Goldenfeld for suggesting this connection between hyper‐systemising and IQ.

‡ Reduced generalisation is seen as a consequence of hyper‐systemising. Systemising presumes that one does not generalise from one system to another until one has enough information that the rules of system A are identical to those of system B. Good generalisation may be a feature of average or poor systemisers, while “reduced” generalisation can be seen as a feature of hyper‐systemising.

‡ ‡ Mind blindness in this model (see fig 1) is seen as arising from twin abnormalities: the SM being set too high, such that complex systems such as the social world are hard to predict via systemising; and atypical development of empathising mechanisms that in the normal case make it possible to make sense of the social world via an non‐SM route.

Competing interests: none declared

Portions of this paper are taken from elsewhere. Reproduced with kind permission from Elsevier (Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, in press[46])46

References

- 1.Asperger H. Die “Autistischen Psychopathen” im Kindesalter. Archiv fur Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten 194411776–136. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frith U.Autism and Asperger's syndrome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991

- 3.Kanner L. Autistic disturbance of affective contact. Nervous Child 19432217–250. [Google Scholar]

- 4.APA DSM‐IV. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994

- 5.Williams J O, Higgins J P T, Brayne C. Systematic review of prevalence studies of autism spectrum disorders. Arch Dis Child 2005908–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison M J, O'Hare A E, Campbell H.et al Prevalence of autistic spectrum disorders in Lothian, Scotland: an estimate using the “capture–recapture” technique. Arch Dis Child 20059016–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey A, Le Couteur A, Gottesman I.et al Autism as a strongly genetic disorder: evidence from a British twin study. Psychol Med 19952563–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Courchesne E. Abnormal early brain development in autism. Mol Psychiatry 2002721–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron‐Cohen S, Ring H, Wheelwright S.et al Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: an fMRI study. Eur J Neurosci 1999111891–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frith C, Frith U. Interacting minds—a biological basis. Science 19992861692–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Happe F, Ehlers S, Fletcher P.et al Theory of mind in the brain. Evidence from a PET scan study of Asperger syndrome. NeuroReport 19968197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heider F, Simmel M. An experimental study of apparent behaviour. Am J Psychol 194457243–259. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perrett D, Smith P, Potter D.et al Visual cells in the temporal cortex sensitive to face view and gaze direction. Proc R Soc Lond 1985B223293–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron‐Cohen S.Mindblindness: an essay on autism and theory of mind. Boston, MA: MIT Press/Bradford Books, 1995

- 15.Baron‐Cohen S. The empathizing system: a revision of the 1994 model of the mindreading system. In: Ellis B, Bjorklund D, eds. Origins of the social mind. London: Guilford, 2005

- 16.Baron‐Cohen S.The essential difference: men, women and the extreme male brain. London: Penguin, 2003

- 17.Baron‐Cohen S. The extreme male brain theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Science 20026248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura D.Sex and cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999

- 19.Baron‐Cohen S, Richler J, Bisarya D.et al The systemising quotient (SQ): an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism and normal sex differences. Philos Trans R Soc 2003358361–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawson J, Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S. Empathising and systemising in adults with and without Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 200434301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R.et al The autism spectrum quotient (AQ): evidence from Asperger syndrome/high functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Dis 2001315–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron‐Cohen S, Hammer J. Parents of children with Asperger syndrome: what is the cognitive phenotype? J Cogn Neurosci 19979548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Happe F, Briskman J, Frith U. Exploring the cognitive phenotype of autism: weak “central coherence” in parents and siblings of children with autism: I. Experimental tests. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 200142299–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermelin B.Bright splinters of the mind: a personal story of research with autistic savants. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2002

- 25.Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Scahill V.et al Are intuitive physics and intuitive psychology independent? Journal of Developmental and Learning Disorders 2001547–78. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah A, Frith U. An islet of ability in autism: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 198324613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jolliffe T, Baron‐Cohen S. Are people with autism or Asperger's syndrome faster than normal on the embedded figures task? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 199738527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Stone V.et al A mathematician, a physicist, and a computer scientist with Asperger syndrome: performance on folk psychology and folk physics test. Neurocase 19995475–483. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers P, Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S.An exact mind. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2004

- 30.O'Riordan M, Plaisted K, Driver J.et al Superior visual search in autism. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 200127719–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plaisted K, O'Riordan M, Baron‐Cohen S. Enhanced visual search for a conjunctive target in autism: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 199839777–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Happe F.Autism. London: UCL Press, 1996

- 33.Baron‐Cohen S, Leslie A M, Frith U. Mechanical, behavioural and Intentional understanding of picture stories in autistic children. Br J Dev Psychol 19864113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leslie A M, Thaiss L. Domain specificity in conceptual development: evidence from autism. Cognition 199243225–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S. Obsessions in children with autism or Asperger syndrome: a content analysis in terms of core domains of cognition. Br J Psychiatry 1999175484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frith U. Studies in pattern detection in normal and autistic children. II. Reproduction and production of color sequences. J Exp Child Psychol 197010120–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plaisted K C. Reduced generalization: an alternative to weak central coherence. In: Burack JA, Charman A, Yirmiya N, Zelazo PR, eds. Development and autism: perspectives from theory and research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001

- 38.Baron‐Cohen S. The mindreading system: new directions for research. Current Psychology of Cognition 199413724–750. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Stott C.et al Is there a link between engineering and autism? Autism: An International Journal of Research and Practice 19971153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baron‐Cohen S, Bolton P, Wheelwright S.et al Does autism occurs more often in families of physicists, engineers, and mathematicians? Autism 19982296–301. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Burtenshaw A.et al Mathematical talent is genetically linked to autism. Human Nature. In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Baron‐Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Willams S.et al Parents of children with autism: an fMRI study. Paper presented at the National Autistic Society conference, London, September 2005

- 43.Fitzgerald M.The genesis of artistic creativity Asperger Syndrome and the Arts. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2005

- 44.Fitzgerald M. Did Ludwig Wittgenstein have Asperger's syndrome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000961–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.James I. Singular scientists. J R Soc Med 20039636–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baron‐Cohen S. The hyper‐systemizing, assortative mating theory of autism. Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. In press [DOI] [PubMed]