Abstract

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is induced by UVB light and reduces UVB-induced epidermal apoptosis; however, the mechanism is unclear. Therefore, wild-type (WT) and COX-2−/− mice were acutely treated with UVB (5 kJ/m2), and apoptotic signaling pathways were compared. Following exposure, apoptosis was 2.5-fold higher in COX-2−/− compared with WT mice. Because prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is the major UV-induced prostaglandin and manifests its activity via four receptors, EP1 to EP4, possible differences in EP signaling were investigated in WT and COX-2−/− mice. Following UVB exposure, protein levels of EP1, EP2, and EP4 were elevated in WT mice, but EP2 and EP4 levels were 50% lower in COX-2−/− mice. Activated cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and Akt are downstream in EP2 and EP4 signaling, and their levels were reduced in UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mice. Furthermore, p-Bad (Ser136 and Ser155), antiapoptotic products of activated Akt and PKA, respectively, were significantly reduced in UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mice. To further study the roles of EP2 and EP4, UVB-exposed CD-1 mice were topically treated with indomethacin to block endogenous PGE2 production, and PGE2, the EP2 agonist (butaprost) or EP4 agonist (PGE1 alcohol), was applied. Indomethacin reduced PKA and Akt activation by ∼60%, but PGE2 and the agonists restored their activities. Furthermore, both agonists decreased apoptosis in COX-2−/− mice by 50%. The data suggest that COX-2–generated PGE2 has antiapoptotic roles in UVB-exposed mouse skin that involves EP2- and EP4-mediated signaling.

Introduction

UV irradiation is a significant environmental factor influencing skin cancer in humans. Among the types of solar radiation, UVB (290−320 nm) is highly carcinogenic compared with UVA (320−400 nm; refs. 1, 2). Acute UVB exposure has been shown to induce cellular damage, most of which will disappear within about 2 weeks (3). However, when UVB exposure is chronic, the repeated exposures cause epidermal cell damage that can lead to skin cancer (1-3).

Prostaglandins are generated via the cyclooxygenases (COX-1 and COX-2) and are known to be increased in the skin following UV exposure (4). COX-1 and COX-2 both catalyze the first reaction in the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins, of which prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is the major product found in UV-exposed skin (5). COX-1 is generally thought to be the constitutively expressed isoform, and COX-2 is the inducible isoform (6). COX-2 is induced in the epidermis by UV exposure (7), and signaling pathways leading to UVB-induced COX-2 induction have been investigated (8). Studies have shown that following acute UV exposure, COX-2 expression/induction contributed to keratinocyte survival and proliferation (5) and reduced apoptosis (9, 10), whereas COX-2 inhibition increased epidermal apoptosis (5, 11). However, the mechanism(s) elicited by COX-2–generated prostaglandins that protect the skin from UV-induced apoptosis are unclear.

PGE2 manifests its biological activities via four known G-protein–coupled membrane receptors: EP1 to EP4 (12, 13). These receptors differ in their PGE2 binding affinities and their downstream signal-transduction pathways. EP2 and EP4 have been reviewed by Regan (12), and both EP2 and EP4 can couple with Gαs protein and activate adenylate cyclase, thereby increasing cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels. EP2 is reported to signal primarily via cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), leading to the phosphorylation of proteins, including cAMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB), which is known to regulate antiapoptotic gene products such as Bcl-2 and IAP (14). PKA also inactivates glycogen synthase kinase (GSK; ref. 12) and proapoptotic Bad by phosphorylation (12, 15). EP4 has also been reported to activate a phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)–dependent pathway leading to the phosphorylation of Akt (12). p-Akt can inactivate several proapoptotic proteins, including Bad, caspase-9, and forkhead, and can activate antiapoptotic proteins including NF-κB and CREB (16). Activated Akt was significantly increased in UVB-irradiated mouse skin (8) and contributed to the resistance of murine keratinocytes to UVB-induced apoptosis (17). However, the role of EP2 and EP4 signaling in UVB-induced apoptosis is not known.

In addition to receptor-mediated pathways, many reports have indicated interactions between COX-2 and p53 (18-20). Studies have shown that p53 is also activated by UV and is important in the suppression of cellular growth and the induction of apoptosis (21, 22) through the induction of Bax, an apoptosis-promoting member of the Bcl-2 gene family (23). p53 has been reported to regulate the expression of COX-2 (18, 19), and prostaglandins produced by COX-2 have been shown to covalently bind wild-type (WT) p53 and prevent its nuclear accumulation (20). Thus, alterations in p53 activity represent an additional mechanism by which COX-2 could influence epidermal responses to UV exposure.

In this study, we extend our previous findings (24) that COX-2 deficiency in vivo increased epidermal apoptosis and describe a possible mechanism. We observed that COX-2 deficiency did not affect UVB-induced p53 or Bax levels. However, it was observed that the PGE2 receptors, EP2 and EP4, and their signaling pathways involving PKA and Akt were decreased in UVB-treated COX-2−/− mice. Finally, we show that exogenous EP2 and EP4 agonists can suppress the increased apoptosis observed in the UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The COX-2 mice used in this study have been maintained for more than 35 generations by heterozygous × heterozygous breeding and are 50% 129Ola/50% C57BL/6 (25). Mice were bred at Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) and housed in the facilities of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) according to the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines. WT and p53 null mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and CD-1 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Female COX mice, p53 mice, and CD-1 mice were used at 6 to 8 weeks of age. All studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at NIEHS. Food and water were provided ad libitum.

The dorsal hair of mice was trimmed 1 day before UVB exposure. To block endogenous PGE2 production, mice were topically treated with indomethacin in acetone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) before treatment with PGE2, the EP2 agonist, butaprost, or the EP4 agonist, PGE1 alcohol (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) in acetone. Restrained mice were UVB irradiated using a UV apparatus (Tyler Research Instruments, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada). The spectra radiance for the UV lamps was 290 to 400 nm, 80% of which is in the UVB range (290−320 nm) and 20% of which is in the UVA range.

Histology and TUNEL assay

The skin was removed from euthanized mice at various times after UVB exposure, fixed immediately in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5-μm thickness. Mounted sections were stained with H&E for light microscopy. Apoptotic cells were detected in paraffin-embedded skin sections by the terminal nucleotidyl transferase–mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Dead-End, Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty microscope fields were counted for each of 3 to 5 mice per genotype.

Western blot analysis

For protein isolation, the dorsal skin was excised, placed on ice, the fat removed, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and homogenized at 4°C with a Polytron homogenizer in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) containing 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Lysates were centrifuged (12,000 × g) for 20 min, and 50 to 100 μg supernatant protein was heated at 95°C in Laemmli loading buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) for 5 min and loaded on Criterion precast gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk-PBST buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature, and the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:500 to 1,000 dilution of the following antibodies: COX-2, COX-1, and EP1 to EP3 (Cayman Chemical), EP4 (Alpha Diagnostic Int., San Antonio, TX), p53 (Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, United Kingdom), p-Akt, Akt, p-GSK3α/β, GSK3α/β, p-Bad, Bax, and p-(Ser/Thr) PKA substrates (Cell Signaling Technology). Equal lane loading was assessed using actin (Sigma-Aldrich). The blots were rinsed thrice with PBST buffer, incubated for 1 h with 1:5,000 dilution of the horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). The proteins were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (GE Healthcare UK Ltd., Buckinghamshire, England).

Akt kinase assay

The measurement of catalytic activity of Akt was carried out by using a nonradioactive Akt kinase assay kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

cAMP immunoassay

cAMP measurement was carried out using a kit from BioVision (Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Calculations were based on a standard curve for each experiment.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by the Student's t test. Differences resulting in P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

UVB increases epidermal apoptosis in WT and COX-2−/− mice

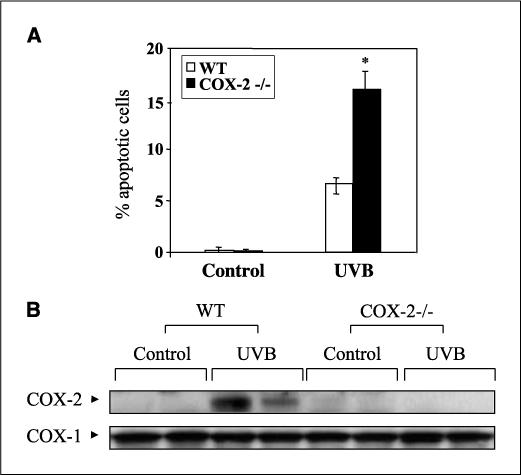

We recently reported that the deficiency of COX-2 reduced UVB-induced PGE2 levels by 35% and increased epidermal apoptosis compared with WT and COX-1−/− mice (24). Figure 1A shows an independent study comparing the levels of apoptosis in WT and COX-2−/− mice at 24 h after UVB exposure. The data indicate that COX-2−/− mice had about 2.5-fold more apoptotic epidermal cells than WT mice. Figure 1B shows that COX-1 protein level was unchanged in UVB-exposed WT and COX-2−/− mice, but that of COX-2 was induced in WT mice by UVB. Based on these observations, we investigated the possibility that the increased apoptosis in COX-2−/− mice was due to decreased PGE2-mediated signaling.

Figure 1.

UVB-induced apoptosis in mouse skin. A, apoptotic cells in WT and COX-2−/− mice were detected by TUNEL assay at 24 h following 5.0 kJ/m2 UVB exposure. Columns, mean (n = 4 mice per group) of the % TUNEL-positive cells per 100 basal cells; bars, SD. *, P < 0.01. B, mice were sacrificed 24 h after 5.0 kJ/m2 UVB irradiation, and isolated protein extracts (50 μg) were electrophoresed, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and the membranes probed using antibodies for COX-2 and COX-1. Each lane represents an individual mouse.

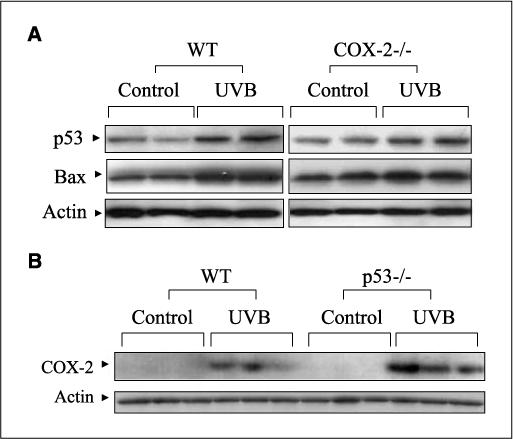

p53 and Bax are induced in UVB-irradiated WT and COX-2−/− mice

COX-2 and p53 are known to have important roles in UV-induced apoptosis, and studies have shown that COX-2 and p53 may interact in regulating UVB-induced apoptosis (26). The role of p53 in apoptosis in part involves the induction of Bax (23), and therefore, the levels of both p53 and Bax proteins were determined in UVB-exposed WT and COX-2−/− mice. Figure 2A shows that p53 and Bax levels were equally induced in WT and COX-2−/− mice at 24 h after UVB treatment. Conversely, whereas COX-2 deficiency did not alter p53 levels, p53 deficiency did lead to increased COX-2 expression following UVB exposure (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that COX-2 does not significantly regulate p53 levels, but p53 can regulate COX-2 expression. In summary, these data suggest that p53 and Bax contribute about equally to apoptosis in WT and COX-2−/− mice and, therefore, do not seem to account for the increased apoptosis observed in COX-2−/− mice.

Figure 2.

UVB-induced p53 and Bax levels in mouse skin. A, WT and COX-2−/− mice were exposed to UVB (5.0 kJ/m2) and sacrificed after 24 h. Protein extracts (50 μg) were electrophoresed, transferred to a membrane, and probed using antibodies for p53 and Bax. Actin served as a control for protein loading and membrane transfer. B, WT and p53−/− mice were exposed to UVB (5.0 kJ/m2) and sacrificed after 24 h. Fifty micrograms of total protein were electrophoresed, and the membrane was probed with an antibody for COX-2. In (A) and (B), two to three mice were used in each experiment, and each experiment was repeated. Each lane represents an individual mouse.

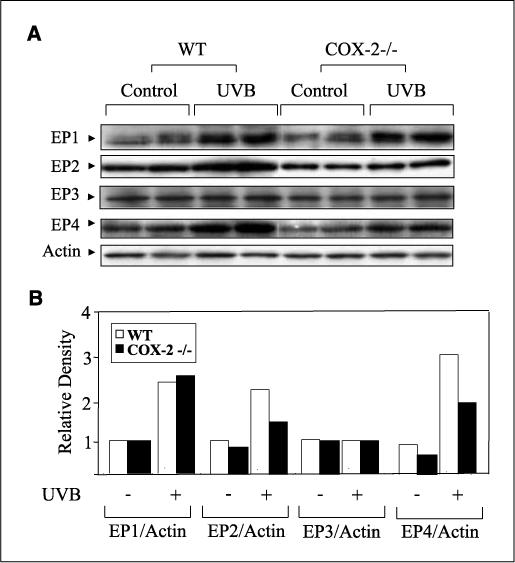

UVB induces PGE2 receptor expression in WT and COX-2−/− mouse skin

PGE2 is the most abundant prostaglandin produced in the skin following UVB exposure (5, 27) and is known to manifest its activity via four membrane receptors, EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4 (12, 13). Therefore, the effect of UVB exposure on the expression of these receptors was determined. Figure 3A shows that the levels of EP1, EP2, and EP4 were increased in WT and COX-2−/− mice following UVB treatment, but that the magnitude of the increase of EP2 and EP4 was decreased in COX-2−/− mice. Figure 3B shows the relative levels of the four PGE2 receptors in control and UVB-exposed WT and COX-2−/− mouse skin. The reduced levels of EP2 and EP4 in COX-2−/− mice suggest that a decrease in the signaling pathways mediated by these receptors may contribute to the increased apoptosis observed in COX-2−/− mice.

Figure 3.

UVB-induced EP2 and EP4 expression was diminished in COX-2−/− mice. A, mice were sacrificed 24 h after UVB irradiation (5.0 kJ/m2), and 50 μg of protein was electrophoresed. Membrane was probed with antibodies for EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4. Two WT and two COX-2−/− mice were used, and each lane represents an individual mouse. The experiment was repeated with similar results. B, fold change of each EP receptor in unexposed and UVB-exposed WT and COX-2−/− mice. Mean densitometry values for replicates of each EP receptor were normalized to actin.

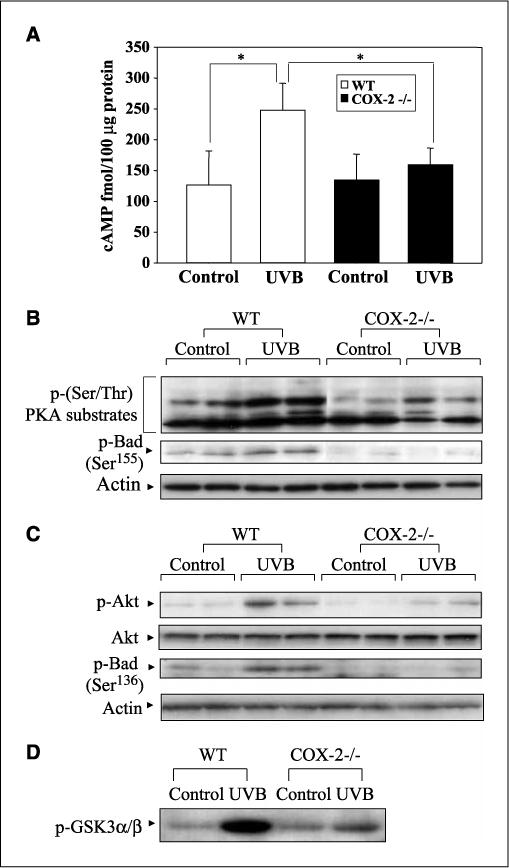

PKA and Akt activation and Bad phosphorylation in the UVB-treated WT and COX-2−/− mouse skin

PGE2 stimulation of EP2 and EP4 has been shown to activate the PKA and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways (12). Because EP2 and EP4 activation of PKA is dependent on cAMP levels (12), the effects of UVB exposure on the levels of cAMP in WT and COX-2−/− mouse skin were determined. UVB treatment increased cAMP levels in WT mouse skin, but did not significantly increase cAMP levels in COX-2−/− mice (Fig. 4A). To investigate PKA activation in WT and COX-2−/− mouse skin, an antibody that recognizes PKA-phosphorylated proteins containing phosphothreonine and phosphoserine in the motifs RXXT and RRXS (28, 29) was used. Figure 4B shows that phosphorylated proteins of different molecular weights were detected, but these PKA-phosphorylated proteins were decreased in UVB-treated COX-2−/− mice.

Figure 4.

UVB-induced EP2 and EP4 activation was diminished in COX-2−/− mice. WT and COX-2−/− mice were sacrificed at 24 h after 5.0 kJ/m2 UVB irradiation. A, tissue lysates containing 100 μg protein were assayed for cAMP level as described in Materials and Methods. Columns, mean; bars, SD (n = 3 mice per genotype). *, P < 0.05. B, total skin protein extracts (100 μg) were electrophoresed and detected using antibodies to p-(Ser/Thr) PKA substrate proteins or p-Bad (Ser155). Each lane represents an individual mouse. C, protein extracts (50−100 μg) were electrophoresed, and the membrane was probed with antibodies for p-Akt or p-Bad (Ser136). Each lane represents an individual mouse. D, tissue lysates containing 200 μg protein were treated with a specific immobilized p-Akt monoclonal antibody. The resulting immunoprecipitates were then incubated with GSK3 fusion protein in the presence of 100 μmol/L ATP. Phosphorylation of GSK3 was measured by Western blotting using the p-GSK3 antibody. In (A) to (D), the data are representative of two independent experiments.

Because the phosphorylation of Bad (Ser155) by PKA can decrease apoptosis (15), the level of Bad phosphorylation at Ser155 in UVB-exposed WT and COX-2−/− mice was determined. As seen in Fig. 4B, the level of p-Bad (Ser155) was significantly reduced in COX-2−/− mouse skin, in agreement with the decreased activity of PKA as determined by the PKA substrate assay. Thus, decreased phosphorylation of Bad by PKA seems to be consistent with the increased apoptosis observed in COX-2−/− mice.

The activation of Akt can also lead to the phosphorylation of Bad (30); therefore, the effect of UVB exposure on Akt activation and the subsequent phosphorylation of Bad (Ser136) in WT and COX-2−/− mice was determined. The data in Fig. 4C indicate that UVB treatment increased the level of p-Akt in WT compared with COX-2−/− mouse skin. The level of unphosphorylated Akt remained constant in both WT and COX-2−/− mice independent of UVB treatment. The reduced Akt activity in COX-2−/− mice was confirmed by demonstrating that GSK3, a substrate for activated Akt, was phosphorylated in vitro to a greater extent by immunoprecipitated Akt from WT mice than COX-2−/− mice (Fig. 4D). The data in Fig. 4C show that the reduced p-Akt level in UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mice leads to reduced p-Bad (Ser136) levels compared with WT mice. Thus, in UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mice, the level of p-Bad, phosphorylated by p-Akt and PKA at two sites (Ser136 and Ser155, respectively), was reduced compared with WT mice and could contribute to the increased apoptosis observed in UVB-treated COX-2−/− mice.

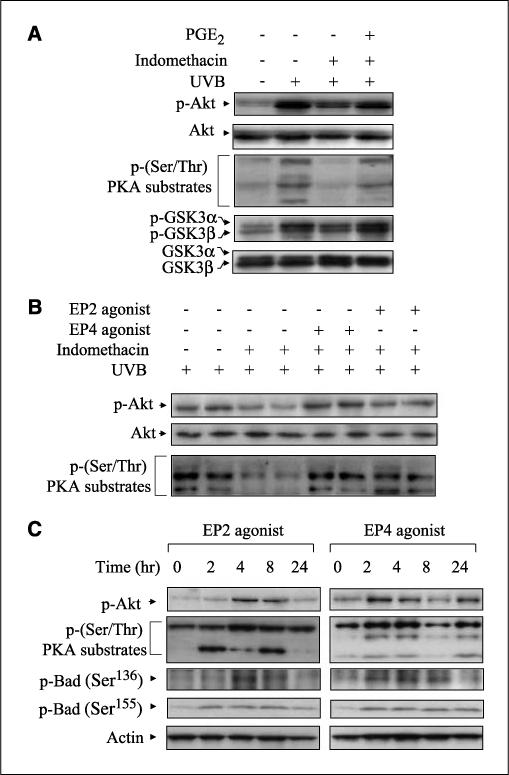

PGE2, EP2, and EP4 agonists stimulate UVB-induced activation of Akt and PKA in CD-1 mouse skin

To more clearly identify the roles of EP2 and EP4 signaling pathways in UVB-exposed skin, CD-1 mice were treated topically with indomethacin before UVB exposure to block endogenous prostaglandin production. Following UVB exposure, the mice were then treated topically with PGE2, the EP2 agonist, butaprost, or EP4 agonist, PGE1 alcohol, to activate EP2 or EP4 signaling. The UVB-induced phosphorylation of Akt and activation of PKA, as measured by phosphorylation of the PKA substrates (28, 29), were decreased by indomethacin pretreatment and restored by exogenous PGE2 (Fig. 5A). In addition, phosphorylation of GSK3α/β, a downstream signaling component of both Akt and PKA, was decreased by indomethacin and restored by exogenous PGE2 (Fig. 5A). These data indicate that PGE2 produced by UVB exposure can activate EP2 and EP4 signaling pathways in mouse skin.

Figure 5.

Effects of PGE2, EP2, and EP4 agonists on the activation of Akt and PKA. A, CD-1 mice were pretreated topically with 50 μg indomethacin 30 min before exposure of 5.0 kJ/m2 UVB and posttreated topically with 5 μg PGE2 30 min after exposure. The animals were sacrificed 24 h following UVB exposure, and protein extracts (50−100 μg) were electrophoresed. Specified bands were detected by immunoblotting, and total Akt and total GSK3α/β served as internal controls. B, CD-1 mice were pretreated topically with 50 μg indomethacin 30 min before UVB (5.0 kJ/m2) exposure and posttreated topically with 25 μg of EP2 or EP4 agonist 30 min after exposure. The mice were sacrificed 24 h after exposure, and total protein was isolated from the dorsal skin. After electrophoresis, the membranes were probed with antibodies for p-Akt and p-(Ser/Thr) PKA substrates. Each lane represents an individual mouse. C, EP agonists (25 μmol) were applied to the backs of CD-1 mice. Mice were sacrificed at the indicated times, and total protein was isolated from the dorsal skin. Membranes were probed using antibodies for p-Akt, p-PKA substrates, and p-Bad (Ser136 and Ser155). In (A) to (C), two mice were used per experiment, and the data are representative of two independent experiments.

To determine if EP2 and EP4 preferentially activated Akt or PKA following UVB exposure, the CD-1 mice were treated topically with indomethacin before UVB exposure and then butaprost or PGE1 alcohol applied. Figure 5B shows that indomethacin suppressed the activation of Akt and PKA, and both were restored by EP2 and EP4 agonists treatment. These data indicate that both agonists had similar effects on Akt and PKA activation at the doses used (Fig. 4B and C).

To determine if EP2 and EP4 agonists could activate Akt and PKA independent of UVB exposure, unexposed CD-1 mice were treated topically with butaprost or PGE1 alcohol. Figure 5C shows that a single treatment with either agonist, in the absence of UVB exposure, induced the phosphorylation of Akt and PKA substrates in CD-1 mouse skin in a time-dependent manner. Furthermore, both agonists also increased the level of p-Bad (Ser136 and Ser155, respectively; Fig. 5C). Thus, the agonists could directly activate EP2 and EP4 signaling in CD-1 mouse skin.

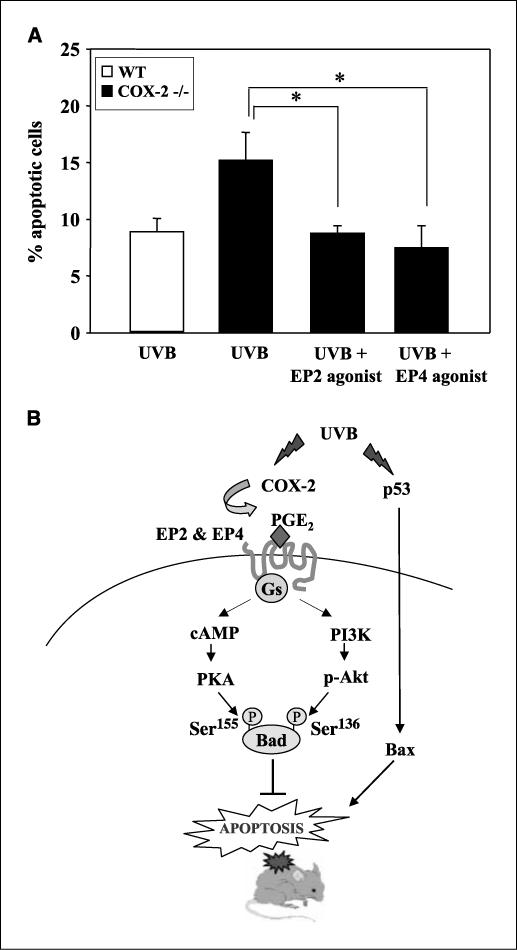

EP2 and EP4 agonists reduce apoptosis in UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mouse skin

To show that reduced PGE2 in COX-2−/− mice and reduced EP2 and EP4 receptor signaling were responsible for the increased apoptosis in UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mouse skin, the effect of EP2 and EP4 agonists on apoptosis in the COX-2−/− mice was determined. The data in Fig. 6A show that epidermal apoptosis, measured by TUNEL staining at 24 h after UVB exposure, was suppressed by ∼50% by pretreatment with either agonist. This reduction in apoptosis resulted in a level of apoptosis about equal to that seen in UVB-exposed WT mice (Fig. 6). These data indicate that the stimulation of EP2 and EP4 receptor-mediated signaling reverses the increased apoptosis observed in UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mice.

Figure 6.

A, effects of EP2 and EP4 agonist on the UVB-induced apoptosis in COX-2−/− mice. EP agonists (25 μmol) were applied to COX-2−/− mice 30 min before UVB exposure (5.0 kJ/m2), and the mice were sacrificed 24 h later. Columns, mean of the percent apoptotic cells (TUNEL positive) per 100 basal cells; bars, SD (n = 5 mice per group). *, P < 0.01. B, a proposed pathway for p53 and EP2/EP4 signaling in UVB-induced epidermal apoptosis.

Discussion

Although studies have shown that COX-2 induction/expression can inhibit apoptosis (10, 31, 32), and that COX-2 inhibition can increase apoptosis (11, 33, 34), little is known about the effects of the mechanism of COX-2. In the present study, using an in vivo model, we investigated the involvement of the PGE2 receptors in UVB-induced apoptosis and show that epidermal apoptosis in COX-2−/− mice is mitigated by EP2 and EP4 agonists. Furthermore, we showed that the EP2- and EP4-mediated reduction in apoptosis was due to increased PKA and Akt activation and subsequent increased levels of antiapoptotic p-Bad.

The tumor suppressor gene, p53, is an important regulator of cell survival following UVB treatment (35, 36), and studies suggest a biochemical link between COX-2 and p53 (18, 19, 37). Therefore, in our initial studies, we hypothesized that increased apoptosis in COX-2−/− mice might be related to increased p53 levels and/or activity. However, UVB-induced levels of p53 and a proapoptotic effector, Bax, were similar in WT and COX-2−/− mice (Fig. 2C). The observation that p53 and Bax were similarly induced in UVB-exposed WT and COX-2−/− mice suggests that they would contribute about equally to UVB-induced apoptosis in both genotypes. Thus, modulation of p53 due to COX-2 deficiency was not the cause of the increased apoptosis observed in UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mice.

Because PGE2 is the major prostaglandin formed in UV-exposed skin (5, 27), we focused on the possible involvement of the PGE2 receptors: EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4. We observed that UVB irradiation induced the expression of EP1, EP2, and EP4 in WT mouse skin, but that expression of EP2 and EP4 was reduced in COX-2−/− mice (Fig. 3A). EP2 and EP4 are coupled to the Gαs, and ligand binding has been reported to increase cAMP levels leading to PKA activation and to activate Akt (12). Akt and PKA activation can mediate prosurvival pathways through the inactivation of proapoptotic proteins including Bad (15, 30). Activated Akt phosphorylates Ser136 of Bad, whereas PKA phosphorylates Ser112 and Ser155 of Bad. The phosphorylation of Bad at Ser112, Ser136, and Ser155 inactivates its proapoptotic function by causing the dissociation of Bad from mitochondrial Bcl-2 and/or Bcl-xL and the binding of p-Bad to the 14−3−3 scaffold proteins (16, 38). In our studies, no differences in the levels of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL were observed between WT and COX-2−/− mice (data not shown). However, UVB activation of both Akt and PKA and phosphorylation of Bad at both Ser136 and Ser155 was decreased in COX-2−/− mice (Fig. 4B and C) and this decreased Bad phosphorylation in COX-2−/− mice compared with WT mice is a likely cause of the increased apoptosis observed in COX-2−/− mice. In support of our in vivo findings, it was recently reported that PGE2 protected gastric mucosal cells in vitro from ethanol-induced apoptosis via EP2 and EP4 activation (39). Additionally, in the mouse intestine, PGE2 activation of EP2 protected the cells from γ-radiation–induced apoptosis (40).

A significant finding of the present study was that both EP2 and EP4 agonists reduced epidermal apoptosis by 50% in UVB-exposed COX-2−/− mice resulting in a level of apoptosis about equal to that observed in WT mice (Fig. 6A). Because COX-2−/− mice showed a 2.5-fold increase in apoptosis (Fig. 1A) and COX-2−/− deficiency reduced PGE2 in UVB-exposed skin by ∼35% (26), the data suggest that the protective effects of the agonists in COX-2−/− mice are mimicking the effects of PGE2 normally generated via COX-2.

Figure 6B illustrates a proposed model showing the roles of p53 and EP2/EP4 in UVB-induced epidermal apoptosis. UVB irradiation induces apoptosis through the induction of p53 and Bax expression in both WT and COX-2−/− mouse skin and presumably is PGE2 receptor independent. UVB also induces COX-2 expression and COX-2–mediated PGE2 production in WT, but not COX-2−/− mice, which results in the activation of the EP2 and EP4 receptors. Activation of these receptors in WT mice increases PKA and Akt activity, which causes multisite phosphorylation of Bad and abrogates the proapoptotic function of Bad and promotes cell survival.

Although in the present paper, we focused on the roles of EP2 and EP4 in the acute epidermal effects of UVB irradiation, the roles of the PGE2 receptors in UV-induced skin tumor formation have received little attention. Tober et al. (41) reported that an EP1 antagonist reduced UVB-induced skin tumor formation in the Skh-1 hairless mouse. Furthermore, Lee et al. (42) reported that EP2 mRNA was increased in UVB-induced papillomas and squamous cell carcinomas, and Tober et al. (43) reported recently that EP2 mRNA levels were significantly elevated in chronically irradiated mouse skin. Based on the effects of the EP2 and EP4 agonists on UVB-induced epidermal apoptosis observed in the present study, further studies are needed to determine the effects of EP2 and EP4 deficiency, as well as of agonists and antagonists for these receptors on UV-induced skin tumor formation during chronic UV exposure.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

We thank Chris A. Lee for animal husbandry and Huei-Chen Lao for mouse genotyping. We also thank Dr. Min-Sub Shim for helpful discussions, and Drs. Colin F. Chignell, Carol Trempus, and Tom Gray and for critically reviewing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Beissert S, Granstein RD. UV-induced cutaneous photobiology. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;31:381–404. doi: 10.3109/10409239609108723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsui MS, DeLeo VA. Longwave ultraviolet radiation and promotion of skin cancer. Cancer Cells. 1991;3:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumura Y, Ananthaswamy HN. Toxic effects of ultraviolet radiation on the skin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;195:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer SM. Is cyclooxygenase-2 important in skin carcinogenesis? J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2002;21:183–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tripp CS, Blomme EA, Chinn KS, Hardy MM, LaCelle P, Pentland AP. Epidermal COX-2 induction following ultraviolet irradiation: suggested mechanism for the role of COX-2 inhibition in photoprotection. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:853–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:145–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckman SY, Gresham A, Hale P, et al. COX-2 expression is induced by UVB exposure in human skin: implications for the development of skin cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:723–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachelor MA, Cooper SJ, Sikorski ET, Bowden GT. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase decreases UVB-induced activator protein-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 in a SKH-1 hairless mouse model. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:90–9. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-04-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsujii M, DuBois RN. Alterations in cellular adhesion and apoptosis in epithelial cells overexpressing prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2. Cell. 1995;83:493–501. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheng H, Shao J, Morrow JD, Beauchamp RD, DuBois RN. Modulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression by prostaglandin E2 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:362–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winters ME, Mehta AI, Petricoin EF, III, Kohn EC, Liotta LA. Supra-additive growth inhibition by a celecoxib analogue and carboxyamido-triazole is primarily mediated through apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3853–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regan JW. EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptor signaling. Life Sci. 2003;74:143–53. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breyer RM, Bagdassarian CK, Myers SA, Breyer MD. Prostanoid receptors: subtypes and signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:661–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. CREB: a stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:821–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lizcano JM, Morrice N, Cohen P. Regulation of BAD by cAMP-dependent protein kinase is mediated via phosphorylation of a novel site, Ser155. Biochem J. 2000;349:547–57. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2905–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butts BD, Kwei KA, Bowden GT, Briehl MM. Elevated basal reactive oxygen species and phospho-Akt in murine keratinocytes resistant to ultraviolet B-induced apoptosis. Mol Carcinog. 2003;37:149–57. doi: 10.1002/mc.10131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subbaramaiah K, Altorki N, Chung WJ, Mestre JR, Sampat A, Dannenberg AJ. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression by p53. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10911–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marwaha V, Chen YH, Helms E, et al. T-oligo treatment decreases constitutive and UVB-induced COX-2 levels through p53- and NFκB-dependent repression of the COX-2 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32379–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moos PJ, Edes K, Fitzpatrick FA. Inactivation of wild-type p53 tumor suppressor by electrophilic prostaglandins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9215–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160241897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe SW, Schmitt EM, Smith SW, Osborne BA, Jacks T. p53 is required for radiation-induced apoptosis in mouse thymocytes. Nature. 1993;362:847–9. doi: 10.1038/362847a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke AR, Purdie CA, Harrison DJ, et al. Thymocyte apoptosis induced by p53-dependent and independent pathways. Nature. 1993;362:849–52. doi: 10.1038/362849a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams PD, Kaelin WG., Jr. Negative control elements of the cell cycle in human tumors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:791–7. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akunda JK, Chun K- S, Sessoms AR, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 deficiency increases epidermal apoptosis and impairs recovery following acute UVB exposure. Mol Carcinog. doi: 10.1002/mc.20290. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langenbach R, Loftin C, Lee C, Tiano H. Cyclooxygenase knockout mice: models for elucidating isoform-specific functions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1237–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swamy MV, Herzog CR, Rao CV. Inhibition of COX-2 in colon cancer cell lines by celecoxib increases the nuclear localization of active p53. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5239–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pentland AP, Mahoney M, Jacobs SC, Holtzman MJ. Enhanced prostaglandin synthesis after ultraviolet injury is mediated by endogenous histamine stimulation. A mechanism for irradiation erythema. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:566–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI114746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt A, Nebreda AR. Inhibition of Xenopus oocyte meiotic maturation by catalytically inactive protein kinase A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4361–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022056399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruce JI, Shuttleworth TJ, Giovannucci DR, Yule DI. Phosphorylation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptors in parotid acinar cells. A mechanism for the synergistic effects of cAMP on Ca2+ signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1340–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimamura H, Terada Y, Okado T, Tanaka H, Inoshita S, Sasaki S. The PI3-kinase-Akt pathway promotes mesangial cell survival and inhibits apoptosis in vitro via NF-κB and Bad. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1427–34. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000066140.99610.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu S, Yu G, Zhu Y, Archer MC. Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression in MCF-10F human breast epithelial cells inhibits proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation, and causes partial transformation. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:847–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun Y, Tang XM, Half E, Kuo MT, Sinicrope FA. Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression reduces apoptotic susceptibility by inhibiting the cytochrome c-dependent apoptotic pathway in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6323–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kern MA, Haugg AM, Koch AF, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition induces apoptosis signaling via death receptors and mitochondria in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7059–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gee J, Lee IL, Jendiroba D, Fischer SM, Grossman HB, Sabichi AL. Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors inhibit growth and induce apoptosis of bladder cancer. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:471–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ouhtit A, Muller HK, Gorny A, Ananthaswamy HN. UVB-induced experimental carcinogenesis: dysregulation of apoptosis and p53 signalling pathway. Redox Rep. 2000;5:128–9. doi: 10.1179/135100000101535447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henseleit U, Zhang J, Wanner R, Haase I, Kolde G, Rosenbach T. Role of p53 in UVB-induced apoptosis in human HaCaT keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:722–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12340708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corcoran CA, He Q, Huang Y, Sheikh MS. Cyclooxygenase-2 interacts with p53 and interferes with p53-dependent transcription and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2005;24:1634–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergmann A. Survival signaling goes BAD. Dev Cell. 2002;3:607–8. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoshino T, Tsutsumi S, Tomisato W, Hwang HJ, Tsuchiya T, Mizushima T. Prostaglandin E2 protects gastric mucosal cells from apoptosis via EP2 and EP4 receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12752–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Houchen CW, Sturmoski MA, Anant S, Breyer RM, Stenson WF. Prosurvival and antiapoptotic effects of PGE2 in radiation injury are mediated by EP2 receptor in intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G490–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00240.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tober KL, Wilgus TA, Kusewitt DF, Thomas-Ahner JM, Maruyama T, Oberyszyn TM. Importance of the EP(1) receptor in cutaneous UVB-induced inflammation and tumor development. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:205–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JL, Kim A, Kopelovich L, Bickers DR, Athar M. Differential expression of E prostanoid receptors in murine and human non-melanoma skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:818–25. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tober KL, Thomas-Ahner JM, Kusewitt DF, Oberyszyn TM. Effects of UVB on E prostanoid receptor expression in murine skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:214–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]