Abstract

Aim

To determine the effect of implementing a clinical pathway, using evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines, for the emergency care of children and adolescents with asthma.

Methods

A prospective, before–after, controlled trial was conducted, which included patients aged 1–18 years who had acute exacerbations of asthma treated in a tertiary care paediatric emergency department. Data were collected for identical 2‐month seasonal periods before and after implementation of the clinical pathway to determine hospitalisation rate and other outcomes. For 2 weeks after emergency visits, the rate at which patients returned to emergency care for worsening asthma was evaluated. A multidisciplinary panel, using national guidelines and a systematic review, developed the pathway.

Results

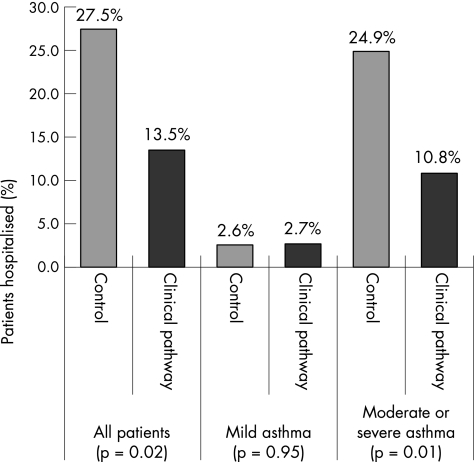

267 patients were studied. The rate of hospitalisation was significantly lower in the post‐implementation group (10/74; 13.5%) than in the pre‐implementation control group (53/193; 27.5%; p = 0.02; number needed to treat 7.1). All reduction in hospitalisation occurred in children with moderate to severe asthma exacerbation. After implementation of the clinical pathway, the rate of administration of oral corticosteroids to patients with moderate or severe exacerbations increased from 71% to 92% (p = 0.01), and significantly more patients received β2‐agonists in the first hour (p = 0.02). No significant change in relapse to acute care occurred within 2 weeks (p = 0.19).

Conclusions

An evidence‐based clinical pathway for children and adolescents with moderate to severe exacerbations of acute asthma markedly decreases their rate of hospitalisation without increased return to emergency care.

Asthma affects nearly 10 million children in the US1 and 1 million children in Canada.2 Its prevalence,3,4,5 morbidity6,7 and mortality5,8 among children have been increasing in many countries for decades. As many as one quarter of the children may develop persistent or relapsing asthma.9 Despite advances in knowledge and treatment, asthma is the leading cause of paediatric hospitalisation in the US10,11 and Canada,12 rates of which continue to rise.5,13,14

Strategies to improve delivery of care and hospitalisation rates for paediatric asthma have been advocated.15,16 Clinical practice guidelines (CPG) may improve adherence to research evidence, optimise delivery of care and reduce unnecessary hospitalisation or treatment. They are effective in treating inpatient paediatric asthma,17,18,19,20 but studies on their effect in acute paediatric care are lacking. Previous studies had outcomes limited to resource utilisation,21 lacked a control group22 or had other methodological limitations.23,24 On the basis of national consensus guidelines25,26,27 and a systematic review, we developed a clinical pathway for emergency care of children with asthma. We then evaluated whether its implementation would improve patient outcomes.

Participants and methods

Study design

We conducted a prospective, before–after, blinded, controlled trial over three consecutive winter periods. Data collection began on 1 February 2000. The control group consisted of two independent cohorts of children with acute asthma who met the study criteria. Data on the first group were obtained between 1 February 2000 and 31 March 2000; and on the second group between 1 February 2001 and 31 March 2001. Data were collected prospectively at each visit to the emergency department, extracted blindly from medical records and combined for overall analysis. The clinical pathway was implemented in December 2001 after staff training. All eligible patients presenting between 1 February 2002 and 31 March 2002 were recruited prospectively and received care under the pathway. Pre‐implementation and post‐implementation groups were further stratified by the initial level of severity of asthma exacerbation. Identical clinical measurements of severity (table 1) were used for both groups. The severity of asthma for controls was determined from these measurements, documented on presentation on structured forms included in the medical chart. For the post‐implementation group, measurement data were recorded on the clinical pathway and chart documents concurrent with each visit to the emergency department. Patients were not made aware of the clinical pathway use; informed consent was not required. Doctors and nurses were unaware of the study. The institutional review board approved this study.

Table 1 Method of determining the severity of an asthma episode.

| Severity* | Accessory muscle use | Wheeze | Dyspnoea | Oxygen saturation (%) on room air | Peak expiratory flow rate (% of predicted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | None or minimal intercostal retractions | Normal breathing or end‐expiratory wheezing | Normal activity and speech or minimal dyspnoea | >95 | >70 |

| Moderate | Intercostal and substernal retractions | Pan‐expiratory wheezing | Decreased activity or speaking 5–8‐word sentences | 91–95 | 51–70 |

| Severe | Nasal flaring or suprasternal retraction | Wheeze audible without stethoscope | Decreased activity or speaking <5‐word sentences | 86–90 | 41–50 |

| Critical | Nasal flaring or paradoxical chest movement | Silent chest or wheeze audible without stethoscope | Unable to speak 1–2‐word sentences or no vocalisations | <86 | ⩽40 |

*An acute episode was rated at a given level of severity if the patient had ⩾2 clinical signs for that level and ⩽1 feature in any other level.

Setting

The study was conducted in the emergency department of a 178‐bed tertiary care hospital (British Columbia's Children's Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada).

Patients

Children and adolescents, aged 1–18 years, who presented to the emergency department with acute exacerbation of asthma were eligible if they had a history of at least two previous episodes of wheeze or a known physician diagnosis of asthma. Acute exacerbation of asthma was defined as wheezing, abrupt or progressive worsening of asthma symptoms or difficulty in breathing, increased use of bronchodilators above the patient's norm, or a decline in peak expiratory flow rate. Selecting eligible patients aged >1 year reduced the likelihood of including patients with bronchiolitis. Patients with critical exacerbation (table 1), need for immediate resuscitation or airway support, concomitant pneumonia, pneumothorax, chronic lung disease or supplemental oxygen requirement, cardiac illness, gastro‐oesophageal reflux, chronic aspiration, neuromuscular disease, stridor, suspected upper airway obstruction or intrathoracic foreign body, immunodeficiency, or contraindication to β2‐adrenergic receptor agonist treatment were excluded. Children with critical exacerbation were excluded because they were expected to require intensive care or treatment not included in the clinical pathway. Pneumonia was defined as fever with evidence of parenchymal infiltrate on a chest radiograph.

Controlgroup care

Timing and selection of treatment for children in the pre‐implementation group were left to the discretion of the doctor. Care was usually initiated after assessment by the doctor, and included nebulised β2‐adrenergic agonists with or without oral corticosteroids. There was no standardised method of practice or established time limits for emergency department care.

Intervention

The intervention was a clinical pathway, based on the CPG, which consisted of assessment and order documentation forms and a plan‐of‐care flowchart indicating treatment and actions of nurses and doctors over the first 8 h in the emergency department according to exacerbation severity. We defined a clinical care pathway as an operational version of a clinical guideline that designates the timing and sequence of assessments and interventions for patients with specific diagnoses.18,28 CPG were defined as systematically developed statements or decision‐making trees, based on available evidence and formulated primarily by specialists, to help practitioners make decisions for managing patients with specific conditions.

Clinicalpathway development

A description of the development of our clinical pathway (fig A) is available online at http://www.archdischild.com/supplemental. Guidelines recommended for use in our clinical pathway were established using recognised methods,29 with recommendations made according to the strength of the supporting evidence.

Assessment at the emergencydepartment

On arrival to triage, nurses screened all patients. Accessory muscle contractions, retractions, wheeze, air entry, speech impairment, transcutaneous oxygen saturation (SaO2) in ambient air by continuous pulse oximetry and peak expiratory flow rate in children ⩾6 years old familiar with peak flow meter use were determined before treatment. Nurses then rated the severity of the episode on presentation as mild, moderate, severe or critical, according to clinical signs (table 1). For controls, severity was rated by the investigator using identical criteria and chart data recorded by nurses and doctors. The episode was rated at a given severity level if the child showed ⩾2 clinical signs for that level and ⩽1 feature in any other level.

Treatment at the emergencydepartment

Patients with mild exacerbation received at least one dose of 5 mg nebulised salbutamol (Ventolin, GlaxoSmithKline, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), administered by a small‐volume nebuliser (Vixone, Westmed, Tuscon, Arizona, USA) in 3 ml normal saline with a well‐fitting facemask, at an oxygen flow rate of 8 l/min, for 10 min. If after ⩾1 h the patient had no wheezing, accessory muscle use or tachypnoea and had an SaO2 >95% in room air, and the doctor permitted discharge from the emergency department, the patient was discharged. Those with moderate or severe exacerbation (MSE) received at least three consecutive doses of nebulised salbutamol, each with a 500‐μg dose of nebulised ipratropium bromide (Atrovent, Boheringer, Burlington, Ontario, Canada), and oral corticosteroids, either dexamethasone 0.2 mg/kg (maximum 8 mg) or prednisone 1 mg/kg (maximum 80 mg). All treatments were to be administered within the first hour. The doctor in the emergency department was notified immediately of children with critical exacerbation, who were not subject to the guideline. Regular assessments served to determine readiness for increasing time between salbutamol doses.

Patientdisposition

Failure to reach discharge criteria was defined as either (1) lack of improvement after ⩾3 treatments with salbutamol and corticosteroid or (2) need for salbutamol more often than every 4 h, after 8 h in the emergency department. Lack of improvement was considered to be persistence of tachypnoea, poor air entry with wheeze, accessory muscle use or SaO2 ⩽94% in room air. Treatments prescribed for home use included the following:

oral prednisone 1 mg/kg (maximum 80 mg) or dexamethasone 0.2 mg/kg (maximum 8 mg) daily for 3 days

salbutamol 5 mg by nebuliser or 200–400 μg by metered‐dose inhaler with valved holding chamber initially every 6 h, tapered to twice daily when improved, over 10 days

nebulised budesonide (Pulmicort, AstraZeneca, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) 1 mg or fluticasone (Flovent, GlaxoSmithKline, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) 125 μg by metered‐dose inhaler with valved holding chamber twice daily for a minimum of 14 days.

Nebulised drugs were to be prescribed for children aged <2 years. Families were told that worsening of symptoms or lack of improvement within 3 days warranted re‐evaluation in our emergency department. All families were instructed to bring the child to a primary care provider for reassessment within 2 days.

Datacollection

For the control group, all clinical data were collected prospectively and systematically on standardised nursing and physician chart record forms. We had ensured that these forms were always present in the medical chart, allowed recording of all relevant data and were identical in content to forms used for the intervention group. Data for patients in the intervention group were recorded on systematic care path forms and the medical chart at each episode. Data were abstracted from clinical pathway forms and charts blinded to admission status and verified for accuracy before database entry. Baseline time was the recorded time of arrival at triage. If severity was not rated on clinical pathway forms, it was determined from data in the hospital chart, if possible. Relevant incomplete charting was noted. Any unscheduled return for asthma or a related diagnosis within 14 days, either to our centre or another city hospital with acute paediatric services, was identified using a computerised administrative database.

Sample size

Using previous observations,30,31,32 we estimated a 30% rate of hospitalisation among patients treated in the absence of a pathway. Sample size calculations were based on an estimated absolute reduction of 15% in the proportion of patients who would be admitted to hospital and two controls per patient in the intervention group. On the basis of these assumptions and the mean baseline estimate of hospitalisation, a two‐tailed power estimate (α = 0.05; power 0.70) required about 84 patients for the intervention and 168 controls to support the null hypothesis.

Statistical analysis

Pre‐implementation and post‐implementation groups were compared according to identical, pre‐specified clinical outcomes, and all analysis was prospective. The primary outcome measure was the rate of hospital admission. Hospitalisation was defined as any admission to the observation unit or the ward during the initial visit to the emergency department. Admission to an observation unit was defined as a stay in the emergency department of >8 h; this was included to remove the effect of availability of inpatient beds and because of higher hospital costs. Admission rates were expressed as the number of children admitted immediately to the hospital divided by the number in the cohort seen in the emergency department. Delayed hospital admission was defined as a subsequent hospitalisation for the same or related diagnosis within 14 days of discharge from the emergency department at the patient's baseline visit.

Other secondary outcomes were as follows: (1) proportion (%) of patients receiving ⩾1 dose of nebulised salbutamol in the first hour in the emergency department; (2) proportion of patients with MSE receiving 3 doses of nebulised salbutamol in the first hour; (3) time to administration of the first salbutamol dose; (4) proportion of patients with MSE receiving oral corticosteroids in the first hour; (5) time to first dose of oral corticosteroids in patients with MSE; (6) ipratropium bromide use in patients with MSE in first hour; (7) rate of unscheduled return to our centre or another local acute hospital within ⩽14 days of the baseline visit to the emergency department for the same or related diagnosis; (8) total time in the emergency department; and (9) proportion of patients given instructions to follow up with a primary care physician within 48 h. Visit duration was the time elapsed from arrival in triage to departure from the emergency department. Time spent in triage counted towards time to first treatments.

χ2 or Fisher's exact test and two‐sided test of proportions were used to characterise any statistical differences between control and intervention groups with respect to categorical variables. Student's t tests were used to evaluate differences in means between two independent samples of normally distributed continuous variables. Wilcoxon's rank sum tests were used for non‐normally distributed numerical data. Patients were analysed within the subgroups of asthma severity to which they were initially assigned on presentation, regardless of any subsequent deterioration. We used stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis to determine the effect of age, sex, baseline inhaled or oral corticosteroid use, baseline severity, initial SaO2 and other characteristics on the primary outcome.

Results

Study sample

We studied 267 patients, after excluding 17. Of these, seven had pneumonia, four had critical exacerbation, three had gastro‐oesophageal reflux, two had bronchopulmonary dysplasia and one had pneumothorax. Baseline characteristics and clinical values for patients in the pre‐implementation (n = 193) and post‐implementation (n = 74) groups were comparable (table 2). Measurements sufficient to determine the severity of asthma were missing in 6 (3%) controls. These were included in overall analyses but excluded from subgroup analyses. In all, 103 (53%) controls and 36 (49%) patients in the clinical pathway group had moderate or severe exacerbation. Very few in either group were sufficiently old or experienced to perform peak expiratory flow. All eligible patients were treated according to the clinical pathway, which was used by all doctors and nurses.

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of study groups.

| Characteristic | Clinical guideline (n = 74) | Control (n = 193) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.1 (3.3) | 5.1 (3.4) |

| Median (IQR25–75) | 4.4 (2.4–6.4) | 4.4 (2.6–6.6) |

| Male (%) | 53 | 65 |

| Chronic inhaled corticosteroid (%)* | 61 | 54 |

| Chronic oral corticosteroid (%)† | 3 | 2 |

| ⩾2 admissions in previous year (%) | 19 | 15 |

| Previous ICU admission (%) | 3 | 2 |

| Previous intubation (%) | 3 | 1 |

| Severity of asthma at baseline (%) | ||

| Mild | 51 | 44 |

| Moderate | 39 | 38 |

| Severe | 10 | 15 |

| Undeterminable | 0 | 3 |

| Mean (SD) oxygen saturation (%) | 96.5 (2.4) | 96.2 (2.6) |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | ||

| >95 | 67 | 68 |

| 91–95 | 26 | 26 |

| 86–90 | 4 | 4 |

| Not recorded | 3 | 2 |

ICU, intensive care unit; IQR25–75, interquartile range from 25th to 75th centile.

*Chronic inhaled corticosteroid is defined as the use of inhaled corticosteroid for ⩾3 months before the baseline visit to the emergency department.

†Chronic oral corticosteroid is defined as the use of oral corticosteroid for ⩾3 weeks before the baseline visit to the emergency department.

Primary outcome

The overall rate of hospital admission (fig 1) decreased from 27.5% (53/193) in the pre‐implementation group to 13.5% (10/74) in the post‐implementation group (p = 0.02). Reduction in hospitalisation was observed entirely among patients with moderate and severe asthma (control group 48/103, clinical pathway group 8/36; p = 0.01). By contrast, no difference in hospitalisation was observed between the two pre‐implementation cohorts, with rates of 27.5% (27/98) in 2000 and 27.4% (26/95) in 2001 (p = 0.98). Analyses adjusted for age, sex, baseline severity, initial SaO2, baseline corticosteroid use and other baseline characteristics did not alter the finding for the primary outcome. Logistic regression analysis showed that corticosteroid administration, giving corticosteroid within the first hour and giving salbutamol within the first hour in the emergency department were independent contributors to reduced hospitalisation. The absolute risk reduction in hospitalisation rate between intervention and control groups was 14% (95% confidence interval (CI) 4% to 24%). The relative risk reduction in hospitalisation exceeded 50% (95% CI 10% to 88%). On the basis of our data, about 7 patients would need to be managed under the pathway to prevent one hospitalisation (number needed to treat 7.1, 95% CI 4 to 33).

Figure 1 Hospitalisation rates in control (pre‐implementation) and clinical pathway (post‐implementation) groups, stratified according to the severity of asthma exacerbation. Percentages refer to proportion of entire group, either pre‐implementation (n = 193) or post‐implementation (n = 74).

Secondary outcomes

Table 3 summarises the secondary clinical outcomes. We found no significant differences between groups regarding the rate of return visit to acute care within 14 days of the baseline visit to the emergency department. The rate of return visit in patients with MSE was 8% (8/103) in the control group and 3% (1/36) in the post‐implementation group (p = 0.3). Delayed hospital admission within 14 days was nearly 6% (8/140) in controls, whereas there were no readmissions (0/64) in the intervention group (p = 0.05). Of the controls who returned after initial discharge from the emergency department, nearly 30% (8/27) were subsequently admitted. No patients required intensive care or intubation, and there were no deaths.

Table 3 Summary of secondary clinical outcomes.

| Clinical guideline | Control | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salbutamol, ⩾1 dose in ⩽1 h (%) | 73 | 58 | 0.02 |

| Salbutamol, 3 doses in ⩽1 h (%)* | 20 | 17 | 0.68 |

| Time to first salbutamol dose (min) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 48 (42) | 56 (45) | 0.04 |

| Median (IQR25–75) | 29 (19–68) | 42 (24–67) | |

| Corticosteroids (%)* | 92 | 71 | 0.01 |

| Corticosteroids in ⩽1 h (%)* | 39 | 23 | 0.04 |

| Time to first corticosteroid dose (min)* | |||

| Mean (SD) | 123 (79) | 107 (88) | 0.50 |

| Median (IQR25–75) | 100 (72–152) | 80 (55–126) | |

| Ipratropium bromide ≥1 dose in ≤1 h (%)* | 36 | 30 | 0.51 |

| Return to ED in ⩽14 days (%) | 8 | 14 | 0.19 |

| Delayed admission in ⩽14 days (%)† | 0 | 6 | 0.05 |

| Documented follow‐up plan (%)‡ | 35 | 27 | 0.19 |

ED, emergency department; IQR25–75, interquartile range from 25th to 75th centile.

*Applied only to patients with moderate or severe exacerbations. These patients were to receive three doses of salbutamol and ipratropium bromide and one dose of oral or intravenous corticosteroids within 1 h of arrival in triage.

†Delayed admission as described in text.

‡Refers to documentation of parental instruction to attend a primary care provider within 48 h of the emergency visit.

The rate of administration of oral corticosteroids to children with MSE, both overall and in the first hour, increased significantly (table 3). A reduction in median time to administration was observed for salbutamol but not for oral corticosteroids. Mean (standard deviation) duration of the emergency department visit did not differ between the two groups (control group, 250 (207) min; clinical pathway group, 254 (215) min).

Discussion

We found that implementation of a clinical pathway for managing acute exacerbations of asthma in children aged ⩾12 months, using an evidence‐based protocol incorporating nationally recognised guidelines, reduced hospital admissions by >50% without an increase in return to acute care. To our knowledge, this is the first study on a clinical pathway for acute paediatric asthma to prove a primary effect on hospitalisation. Our data contribute further evidence of the strength of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and Canadian Asthma Consensus guidelines. Evidence of improved outcomes has been sought33,34,35 to justify broad implementation of asthma guidelines. Use of an evidence‐based pathway could have a major effect on improving overall care and reducing unnecessary hospitalisation of children and adolescents with acute asthma.

In a before–after study using data extracted from computerised medical records, Browne et al23 reported a similar reduction in hospitalisation, from 32% to approximately 19%, after introduction of their asthma pathway. However, hospitalisation rate was not a predefined outcome in their study. The primary outcome, inclusion criteria, specific treatment sequence and statistical methods were not clearly defined in the published article. Al‐Mogbil et al24 found no observable change in hospitalisation after introduction of their pathway. However, their study was retrospective, and hospitalisation was not a primary measure. Uniquely, we also observed a reduction in delayed hospitalisation, with no admissions in the intervention group on re‐presentation to the emergency department. This may be a further effect of the pathway.

As observed in the pre‐implementation period, healthcare providers, including paediatricians, do not adhere consistently to nationally recognised management guidelines.36,37,38,39,40 Recent studies suggest that underutilisation of these guidelines is common and may relate partly to a lack of understanding or knowledge.41,42,43 Treatment of preschool children in the emergency department may be particularly inadequate.44 Provision of oral corticosteroids to our control group was similar to that reported in other paediatric centres.45 Our relapse rates were marginally higher than those observed at some centres,6,46,47 but lower than those of others.48,49 Thus, our providers were not necessarily less “compliant” with published standards. Implementing a new clinical pathway is a challenging process, described in detail previously.50 However, paediatric emergency staff are capable of adhering to most guidelines for management of acute asthma.51 Clinical practice guidelines are more likely to be followed if they are developed in collaboration with users and are concise, flexible, rigorously tested and based on improving quality of care.35

Enabling nurses to initiate interventions with our clinical pathway possibly reduced treatment delays. Application of multiple evidence‐based practices was also more consistent. Chiefly, more frequent administration of corticosteroids to children with MSE in the post‐implementation group may have improved their hospitalisation rate, as supported by other studies.44,52,53 Moreover, we observed a considerable increase in administration of oral corticosteroids to patients with MSE in the first hour. This has also been associated with reduced hospitalisation.44 Patients who respond completely to 1–2 doses of β2‐adrenergic agonists may be regarded as having mild exacerbation and do not require oral corticosteroids in the first hour.27 Oral corticosteroids are as effective as intravenous corticosteroids.27,54,55 Use of admission criteria defined in the guidelines may have reduced other influences on hospitalisation, such as inter‐physician practice variations, subjective factors and bias in hospitalisation decisions. Additional improvement in hospitalisation rates might be achieved with increased use of ipratropium bromide in children with MSE,30,56,57,58,59 and reduction in time to oral corticosteroid delivery.

Although asthma scores help to describe the severity of exacerbation and possibly response to treatment,60,61 no baseline scoring system has been shown to have sufficient predictive validity for use in disposition of acute paediatric asthma. We therefore believed it was necessary to include patients with initially mild exacerbations in our study. Our clinical pathway also indicated that all patients who were given oral corticosteroids and observed for a further 2 h without requiring additional salbutamol could be discharged home. Scarfone et al52 showed that most patients who were initially thought to require hospitalisation 2 h after oral corticosteroids could be safely discharged by 4 h.

The study was designed such that the intervention interrupted repeated measurement in a control period, while minimising the duration of the study, to reduce the effect of secular trends. Our sampling strategy tried to avoid seasonal bias while ensuring adequate accrual of cases. Discrete pre‐implementation cohorts helped to establish baseline trends. Admission rates for children in both pre‐implementation periods were identical, whereas the rate for the post‐implementation group was considerably lower. All data were prospectively collected, thus less likely to be subject to error and omission. Our severity assessment method was modified from that of Schuh et al,56 using reliable and validated parameters.62,63,64,65,66,67,68

Limitations

This study was limited to a single, urban, paediatric tertiary care emergency department; our findings may therefore not be generalisable to other settings. Knowledge that the child was being managed under a clinical pathway may have unduly influenced hospitalisation decisions, as would a potential Hawthorne effect.69 However, hospitalisation was predefined such that use of an observation unit, bed availability or any time limits of emergency department care would not affect measured hospitalisation rates. Visit duration did not differ between groups, so this would not contribute to hospitalisation differences.

We studied groups sequentially rather than concurrently to avoid the confounding effects of staff knowledge and experience with the clinical pathway on the management of controls. Evaluating guidelines through a parallel randomised trial poses the risk that treatment offered to controls will be affected by doctors' knowledge of the guidelines, leading to an underestimate of the true effect of the guidelines.69 Despite our congruent sampling strategy and modest study duration, secular trends may still have influenced study observations. Environmental changes, variations in primary care practice, use of various controller drugs and educational strategies may have affected hospitalisation rates. However, baseline features, including the rates of inhaled and oral corticosteroid use, were comparable between groups and did not contribute in adjusted analyses. Epidemiological data collected at our centre over the study years did not indicate important differences in documented viral infections. Further, a systematic review found no definite evidence that education about asthma for children who have attended the emergency department reduces subsequent visits or hospital admissions.70 A multicentre cluster randomised trial is therefore recommended to consolidate the study findings.

Whatis already known on this topic

Clinical pathways are effective for inpatient paediatric asthma.

Little is known about their effect on acute care.

Whatthis study adds

Use of an evidence‐based clinical pathway for emergency management of asthma markedly reduced hospital admissions in children with moderate to severe asthma exacerbation.

After implementation of the clinical pathway, time to initiation of salbutamol improved considerably, and an increased proportion of children with moderate to severe asthma received corticosteroids.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

CPG - clinical practice guidelines

MSE - moderate or severe exacerbation of asthma

SaO2 - oxygen saturation

Footnotes

Funding: The guideline development, implementation and study were funded jointly by the Divisions of Paediatric Emergency Medicine and Quality Promotion, Children's and Women's Health Centre of British Columbia, Canada. No other financial relationships are applicable to any author. The Division of Pharmaceutical Outcomes at the Children's and Women's Health Centre of British Columbia provided additional professional human resources.

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: SPN supervised and contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data and the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; SPN acts as the guarantor. He was also a participating member of the Emergency Asthma Clinical Practice Guideline Committee at British Columbia's Children's Hospital, Children's and Women's Health Centre of British Columbia at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. MVP contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. FT provided statistical expertise analysis and contributed to the interpretation of data. SH supervised the Emergency Asthma Clinical Practice Guideline Committee at British Columbia's Children's Hospital, Children's and Women's Health Centre of British Columbia, and contributed to the conception and design of the study, data collection and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. BCC contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and was a participating member of the Emergency Asthma Clinical Practice Guideline Committee.

References

- 1.Dey A N, Bloom B. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2003, National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2005101–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Canada National Population Health Survey Overview, 1996–97. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1998

- 3.Grant E N, Wagner R, Weiss K B. Observations on emerging patterns of asthma in our society. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999104S1–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beasley R, Crane J, Lai C K, Pearce N. Prevalence and etiology of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000105S466–S472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akinbami L J, Schoendorf K C. Trends in childhood asthma: prevalence, health care utilisation, and mortality. Pediatrics 2002110315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens M W, Gorelick M H. Short‐term outcomes after acute treatment of paediatric asthma. Pediatrics 20011071357–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newacheck P W, Halfon N. Prevalence, impact, and trends in childhood disability due to asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000154287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao Y, Semenciw R, Morrison H.et al Increased rates of illness and death from asthma in Canada. Can Med Assoc J 1987137620–624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sears M R, Greene J M, Willan A R.et al A longitudinal, population‐based, cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med 20033491414–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith D H, Malone D C, Lawson K A.et al A national estimate of the economic costs of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997156787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owens P L, Thompson J, Elixhauser A.et alCare of children and adolescents in US hospitals. AHRQ Publication Number 04‐0004. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2003

- 12.Millar W J, Hill G B. Childhood asthma. Health Rep 1998109–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gergen P J, Weiss K B. Changing patterns of asthma hospitalisation among children: 1979–1987. JAMA 19902641688–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention Asthma mortality and hospitalisation among children and young adults—United States, 1980–1993. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 199645350–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara M, Rosenbaum S, Rachelefsky G.et al Improving childhood asthma outcomes in the United States: a blueprint for policy action. Pediatrics 2002109919–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Department of Health and Human Services Access to quality health services. In: Healthy people 2010. Vol 1, 2nd edn. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 20001–3147.

- 17.Johnson K B, Blaisdell C J, Walker A.et al Effectiveness of a clinical pathway for inpatient asthma management. Pediatrics 20001061006–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wazeka A, Valacer D J, Cooper M.et al Impact of a paediatric asthma clinical pathway on hospital cost and length of stay. Pediatr Pulmonol 200132211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly C S, Andersen C L, Pestian J P.et al Improved outcomes for hospitalised asthmatic children using a clinical pathway. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 200084509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDowell K M, Chatburn R L, Myers T R.et al A cost‐saving algorithm for children hospitalised for status asthmaticus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998152977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg R, Chan L, Haley P.et al Critical pathway for the emergency department management of acute asthma: effect on resource utilisation. Ann Emerg Med 199831562–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Press S, Lipkind R S. A treatment protocol of the acute asthma patient in a paediatric emergency department. Clin Pediatr (Phil) 199130573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Browne G J, Giles H, McCaskill M E.et al The benefits of using clinical pathways for managing acute paediatric illness in an emergency department. J Qual Clin Pract 20012150–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al‐Mogbil M H, Plint A, Gaboury I.et al Evaluating an asthma critical pathway in a paediatric emergency department [abstract]. Paediatr Child Health 20038B32B [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ernst P, Fitzgerald J M, Spier S. Canadian Asthma Consensus Conference. Can Respir J 1996389–100. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boulet L P, Becker A, Bérubé D.et al Canadian Asthma Consensus Report 1999. Can Med Assoc J 1999161(Suppl 11)S1–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute New NHLBI guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Lippincott Health Promot Lett 199721, 8–1, 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitchiner D, Bundred P. Integrated care guidelines. Arch Dis Child 199675166–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shekelle P G, Woolf S H, Eccles M.et al Clinical guidelines: developing guidelines. BMJ 1999318593–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qureshi F, Zaritsky A, Lakkis H. Efficacy of nebulized ipratropium in severely asthmatic children. Ann Emerg Med 199729205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schuh S, Johnson D W, Stephens D.et al Hospitalisation patterns in severe acute asthma in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 199723184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baren J M. The acute asthmatic in the pediatric emergency department: to admit or discharge. In: Brenner BE, ed Emergency asthma. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1999

- 33.Bauchner H, Homer C, Salem‐Schatz S R.et al The status of paediatric practice guidelines. Pediatrics 199799876–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crain E F, Weiss K B, Fagan M J. Paediatric asthma care in US emergency departments. Current practice in the context of the National Institutes of Health guidelines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1995149893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores G, Lee M, Bauchner H.et al Paediatricians' attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding clinical practice guidelines: a national survey. Pediatrics 2000105496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grunfeld A, Beveridge R C, Berkowitz J.et al Management of acute asthma in Canada: an assessment of emergency physician behaviour. J Emerg Med 199715547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Legorreta A P, Christian‐Herman J, O'Connor R D.et al Compliance with national asthma management guidelines and specialty care. Arch Intern Med 1998158457–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finkelstein J A, Lozano P, Shulruff R.et al Self‐reported physician practices for children with asthma: are national guidelines followed? Pediatrics 2000106886–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halterman J S, Aligne C A, Auinger P.et al Inadequate therapy for asthma among children in the U.S. Pediatrics 2000105272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan S D, Weiss K B, Lynn H.et al The cost‐effectiveness of an inner‐city asthma intervention for children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002110576–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doerschug K C, Peterson M W, Dayton C S.et al Asthma guidelines: an assessment of physician understanding and practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19991591735–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell I, Choi B C K, McRae L.et al Asthma in children: management practices among paediatricians and family physicians. Paediatr Child Health 20016355–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark N M, Gong M, Schork M A.et al Impact of education for physicians on patient outcomes. Pediatrics 1998101831–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rachelefsky G. Treating exacerbations of asthma in children: the role of systemic corticosteroids. Pediatrics 2003112382–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milks C J, Oppenheimer J J, Bielory L. Comparison of emergency room asthma care to National Guidelines. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 199983208–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chapman K R, Verbeek P R, White J G.et al Effect of a short course of prednisone in the prevention of early relapse after the emergency room treatment of acute asthma. N Engl J Med 1991324788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emerman C L, Cydulka R K, Crain E F.et al Prospective multicenter study of relapse after treatment for acute asthma among children presenting to the emergency department. J Pediatr 2001138318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gouin S, Macarthur C, Parkin P C.et al Effect of a paediatric observation unit on the rate of hospitalisation for asthma. Ann Emerg Med 199729218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kerem E, Tibshirani R, Canny G.et al Predicting the need for hospitalisation in children with acute asthma. Chest 1990981355–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Studdert J, Ramsden C. Introduction of standardised emergency department paediatric asthma clinical guidelines into a general metropolitan hospital. Accid Emerg Nurs 2005132–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scribano P V, Lerer T, Kennedy D.et al Provider adherence to a clinical practice guideline for acute asthma in a paediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 200181147–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scarfone R J, Fuchs S M, Nager A L.et al Controlled trial of oral prednisone in the emergency department treatment of children with acute asthma. Pediatrics 199392513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grant C C, Duggan A K, DeAngelis C. Independent parental administration of prednisone in acute asthma: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, crossover study. Pediatrics 199596224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Younger R E, Gerber P S, Herrod H G.et al Intravenous methylprednisolone efficacy in status asthmaticus of childhood. Pediatrics 198780225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barnett P L, Caputo G L, Baskin M.et al Intravenous versus oral corticosteroids in the management of acute asthma in children. Ann Emerg Med 199729212–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schuh S, Johnson D W, Callahan S.et al Efficacy of frequent nebulized ipratropium bromide added to frequent high‐dose salbutamol therapy in severe childhood asthma. J Pediatr 1995126639–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qureshi F, Pestian J, Davis P.et al Effect of nebulized ipratropium on the hospitalization rates of children with asthma. N Engl J Med 19983391030–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zorc J J, Pusic M V, Ogborn C J.et al Ipratropium bromide added to asthma treatment in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics 1999103748–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plotnick L H, Ducharme F M. Combined inhaled anticholinergics and beta2‐agonists for initial treatment of acute asthma in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20031CD000060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van der Windt D A, Nagelkerke A F, Bouter L M.et al Clinical scores for acute asthma in pre‐school children. A review of the literature. J Clin Epidemiol 199447635–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van der Windt D A. Promises and pitfalls in the evaluation of paediatric asthma scores. J Pediatr 2000137744–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Angelilli M L, Thomas R. Inter‐rater evaluation of a clinical scoring system in children with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 200288209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yung M, South M, Byrt T. Evaluation of an asthma severity score. J Paediatr Child Health 199632261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Becker A B, Nelson N A, Simons F E. The pulmonary baseline: assessment of a clinical score for asthma. Am J Dis Child 1984138574–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kerem E, Canny G, Tibshirani R.et al Clinical‐physiologic correlations in acute asthma of childhood. Pediatrics 199187481–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ducharme F M, Davis G M. Respiratory resistance in the emergency department: a reproducible and responsive measure of asthma severity. Chest 19981131566–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smith S R, Baty J D, Hodge D I I I. Validation of the pulmonary score: an asthma severity score for children. Acad Emerg Med 2002999–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gorelick M H, Stevens M W, Schultz T R.et al Performance of a novel clinical score, the Paediatric Asthma Severity Score (PASS), in the evaluation of acute asthma. Acad Emerg Med 20041110–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grimshaw J M, Russell I T. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet 19933421317–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haby M M, Waters E, Robertson C F.et al Interventions for educating children who have attended the emergency room for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20011CD001290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.