Abstract

This article reviews the evidence for the current UK Department of Health recommendations for prevention of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and suggests other factors that should be considered. The wording of the Department of Health recommendations for SIDS prevention has changed over the past 6 years, but the specific recommendations are largely consistent with the scientific evidence. The emphasis on thermal and illness factors and immunisation could be reduced. Bed sharing and sharing the parental bedroom should be given more emphasis. Two major recommendations need to be discussed in greater detail: (1) breast feeding and (2) pacifier use. Meta‐analyses or reviews looking at each risk factor or a combination of risk factors are required. Further, it is recommended that a committee is established that reviews the recommendations and publishes the evidence that leads to these recommendations, as is done by the American Academy of Pediatrics Taskforce on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

The “Back to Sleep” campaign began in December 1991 in England and Wales, following the lead of The Netherlands, New Zealand and Australia. The campaign has been spectacularly successful, with mortality from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) more than halved. However, SIDS remains a leading cause of mortality in the first year of life. On the basis of evidence that sleep position is causally related to SIDS, advice has been offered to parents on other infant care practices that might be implicated in SIDS. The UK Department of Health has issued advice on the prevention of cot death three times since 2000.1,2,3 The statements usually provide simple messages for the public, but the evidence for these recommendations has not accompanied this advice. In most instances, the new advice is offered because there is new information. At times, specific messages are dropped without explanation. In my opinion, some of the current advice is based on limited information. The American Academy of Pediatrics Taskforce on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome periodically provides evidence‐based advice.4,5,6 Its advice may stimulate heated debate,7 but at least it enables others to judge the evidence for themselves.

The advice given to parents by the Department of Health is in the pamphlet entitled “Reduce the risk of cot death”. Although it is not specified in the pamphlet, the Department of Health uses the Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths definition of cot death. The Foundation for the Study of Infant Deaths definition equates cot death with sudden unexpected death in infants (SUDI).8 Some SUDI cases can be explained after a thorough autopsy and examination of the circumstances of death. Those that remain unexplained are certified as SIDS. However, this definition of cot death is not used by others. The World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases (ICD) classifies cot death (or crib death in the US) under the rubric SIDS (ICD9 797.0; ICD10 R95), and thus cot death is synonymous with SIDS, not with SUDI. The pamphlet mixes SIDS‐specific prevention messages with general advice, and yet omits other advice that is associated with reduced infant mortality, such as breast feeding9 and immunisations.10

This paper reviews the recent changes in recommendations as they relate to SIDS, reviews the evidence for the current recommendations and suggests other factors that should be considered. The aim is to stimulate debate and encourage the establishment of a committee to advise the Department of Health on strategies to prevent SIDS.

The changing recommendations

Table 1 summarises the recommendations of the Department of Health in 2000, 2004 and 2005, and whether they have changed. I found no changes in the messages between 2004 and 2005, although there were minor changes in the layout of the pamphlet (“Reduce the risk of cot death”). Although some of the wording changed between 2000 and 2004/5, many of the recommendations in essence remain the same.

Table 1 The Department of Health recommendations for SIDS prevention in 2000 and 2004, and whether they have changed.

| 20001 | 20042 and 20053 | Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Place baby on its back to sleep | Place your baby on the back to sleep | No change |

| Create a smoke‐free zone around your baby | Do not let anyone smoke in the same room as your baby | No change |

| Do not smoke or let your partner smoke near you when you are pregnant | Cut smoking in pregnancy,—fathers too! | No change |

| Do not let your baby get too hot | Do not let your baby get too hot | No change |

| Place your baby in the “feet to foot” position | Keep your baby's head uncovered—place your baby in the “feet to foot” position | No change |

| Have your baby immunised, there is evidence to show this reduces the risk of cot death | Dropped | |

| Do not fall asleep on a sofa with your baby | Now included in the section on keeping head uncovered | |

| If you are a smoker, have been drinking alcohol, are very tired or if you are taking drugs or medication that may make you sleepy do not share a bed with your baby | Do not share a bed with your baby if you have been drinking alcohol, take drugs or if you are a smoker | No change |

| Keep your baby's cot in your bedroom for the first six months of life | Now included in the section on keeping head uncovered: “The safest place for your baby to sleep is in a cot in your room for the first six months of life” | |

| If your baby is unwell, seek prompt advice | Previously included in general advice |

Department of Health recommendations

Sleeping position

That there is a causal association between prone sleeping position and SIDS is beyond dispute. Many case–control studies identified the association,11,12 and there has been a close temporal relationship between when the “Back to Sleep” recommendation was made and the fall in SIDS and total postneonatal mortality.13,14

Most studies15,16,17,18,19 but not all20 find an association between side sleeping position and SIDS. The reduction in side sleeping position is probably resulting in the ongoing but smaller fall in SIDS and all‐cause postneonatal mortality. Side sleeping position doubles the risk of SIDS, probably owing to the side position being relatively unstable, resulting in some infants turning to the prone position.

Maternal smoking in pregnancy

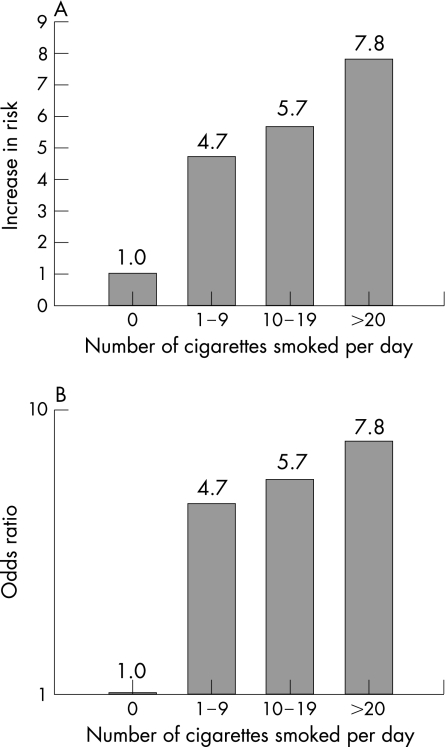

More than 60 studies have shown that maternal smoking in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of SIDS, and the magnitude of the effect seems even larger since the reduction in SIDS.21,22,23,24 Many of the studies show a dose effect; the more that is smoked the higher the risk of SIDS. This is often displayed on a linear scale as in the “Reduce the risk of cot death” pamphlet (fig 1). The recommendation to reduce the amount smoked is valid, but fig 1 shows that the greatest benefit is obtained by reducing the amount smoked by those who smoke the most. In fact, the odds ratios (ORs) are additive on a logarithmic scale, and thus the greatest benefit is achieved by getting light smokers to stop rather than heavy smokers to reduce the amount smoked. Using the ORs in the Department of Health figure, reducing maternal smoking from >20 cigarettes per day to 10–19 per day lowers the risk by one quarter, whereas getting those who smoke 1–9 per day to stop lowers their risk by three quarters.

Figure 1 The risk of sudden infant death syndrome and the number of cigarettes smoked on a linear scale (A) and the correct logarithmic scale (B).

The recommendation that partners should not smoke near the mother when she is pregnant is based on limited evidence. The effect of paternal smoking in the absence of maternal smoking on birth weight is estimated to be <30 g,25 it is thus unlikely that sufficient tobacco products would cross the placenta and alter SIDS risk.

Environmental tobacco smoking

It is difficult to separate the effects of postnatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure from earlier effects of smoking in pregnancy.26 One way to do this is to examine the effects of paternal smoking where the mother is a non‐smoker. The summary OR has been estimated to be 1.47, which is considerably less than that for maternal smoking, suggesting the predominant effect is in utero.24

Alternatively, one can look at the effect of smoking by household members other than that of the parents. Four studies have examined smoking by other household members and either adjusted for maternal smoking27,28,29 or restricted the analysis to maternal non‐smokers.30 Two studies showed a small statistically significant increased risk,27,30 and two showed no additional risk.28,29

Thermal factors

Case–control studies before the “Back to Sleep” campaigns showed that there was an increased SIDS risk with thermal factors, such as heating being on all night and excess clothes and bedding.31,32,33,34 Further examination of these studies has shown that the increased risk with thermal factors is predominantly among infants sleeping in the prone position. In recent studies where few infants sleep prone, there is limited evidence that these thermal factors are important.16,35 The emphasis on this factor could be considerably reduced, and possibly removed.

Head covering

Many case series have reported that 25–40% of infants found dead have their heads covered by bedding.16,19,36,37,38 Whether this is an agonal event or part of the causative pathway has never been established. If it is causally related to SIDS, then attempts to avoid this occurring makes excellent sense. Beal39 recommended not having any bedclothes. It has been postulated that placing infants in a sleeping sack reduces the risk of head covering and thus their risk of SIDS.36 Placing infants at the foot of the cot (“feet to foot”) and thus reducing the chance of head covering is an attractive idea, but there is no evidence suggesting that this lowers the risk of SIDS.16 Unfortunately, if the cots are large enough that the infant can be placed at the foot, they are often wide enough to allow the infant to twist sideways under the blankets. These suggestions are based on little evidence and need further study before they are recommended.

Bed sharing

This remains controversial although the epidemiological evidence is clear. Bed sharing increases the risk of SIDS.19,40,41,42,43,44 Most19,40,41,43,44 but not all42 studies show that the increased risk of SIDS with bed sharing is predominantly among infants of mothers who smoke. The major controversy is whether infants of non‐smoking mothers are at increased risk. Individually, only some studies have shown an effect,20,44 but a meta‐analysis has shown an increased risk.15 More recently, however, the European Concerted Action on SIDS Study has shown an interaction among infant age, smoking and bed sharing.19 Infants aged <12 weeks born of non‐smokers are at increased risk of SIDS with bed sharing compared with infants of non‐smoking mothers not bed sharing.45 However, this increased risk is quite small compared with infants of maternal smokers who bedshare.

Some have argued that it is the type of families that share beds that increases the risk rather than bed sharing itself,46 but this is unlikely. The fact that infants who are placed back in the cot after breast feeding or cuddles are not at increased risk, and that the risk increases with the duration of bed sharing, suggests that the problem is related to bed sharing rather than other factors.

Sleeping with older siblings is especially dangerous. No data are available on whether twins sleeping together are at similar high risk.

The mechanism by which cosleeping increases the risk of SIDS is unknown. Postulated mechanisms include airway obstruction, thermal stress, head covering and hypoxia due to rebreathing of expired gases. Cosleeping promotes infant arousals,47 which does not support the hypothesis that arousal defects may be part of the causal pathway for SIDS.48

Sofa

Infants sleeping on a sofa have been shown in UK studies to be at risk, both in itself and when sharing the sofa with an adult.16,42 Although the attributable risk is between 6% and 10%, the risk is high and avoidable. It would therefore seem reasonable to maintain this message.

Sharing the parental bedroom

Sharing the parental bedroom, but not the parental bed, has been shown in several studies to be associated with a reduced risk of SIDS compared with infants sleeping in a separate bedroom with or without siblings.19,42,43,49 It is not clear why babies sleeping in the parent's bedroom are at reduced risk of SIDS. The recent advice from the Department of Health “The safest place for your baby to sleep is in a cot in your room for the first six months of life” covers this and cosleeping, but the advice is not explicit as to which components are most important.

Illness and infection

“If your baby is unwell, seek prompt advice” was added to the specific SIDS prevention advice in 2004. Although there is a relationship between illness, usually mild, and SIDS, mild illness is prevalent among the controls, and thus few infants who are unwell will subsequently die of SIDS32,33,35,50 or an explained cause. Infection has been shown to interact with sleeping position, so that infection is only a risk for SIDS in prone‐sleeping infants.33 A recent study from Germany has shown that infection is not a risk factor for SIDS in a population where few infants sleep prone.50 Thus, illness recognition might be dropped from SIDS prevention advice, although retained in general advice to parents. Although the Department of Health pamphlet provides guidelines as to which symptoms families should take particular notice of, this is not readily available. In New Zealand, a list of such symptoms and signs (“Danger signals”) are on the back of the parent‐held Well child health book, and thus are readily available.51

Immunisation

As immunisations in the first year of life are given around the time of the peak incidence of SIDS, it is not unexpected that some deaths will occur in close temporal relationship with immunisation, which has led to the suggestion that immunisations cause SIDS.52,53 Several studies have examined this relationship, and most suggest that the risk of SIDS is lower in immunised infants than in those not immunised.54,55,56,57 The association is weakened after controlling for socioeconomic status. Probably, the reduced risk is explained by socioeconomic factors and children who had minor illnesses were not immunised. The UK is the only country that included this among its recommendations for SIDS prevention. It seems appropriate to drop this recommendation as a SIDS prevention strategy, but of course maintain it in the general advice to parents.

Safe sleeping environment

Avoidance of soft sleeping surfaces, pillows, duvets and sheepskins has been recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.5,6 Infants using an adult pillow seem to be at increased risk of SIDS,41,58,59 but the association with duvets is complex. Duvets vary in size from being the size of the mattress as in Australia to being larger and able to be tucked in as in the UK and New Zealand.60 This makes extrapolation from one study to another more difficult. Most studies,19,37 but not all,60 have shown an increased risk of SIDS with duvets, which may partly be related to the thermal properties and partly to the risk of head covering and rebreathing of expired air. The increased risk may also be related to bed sharing with an adult, but this has not been examined in detail.

Other recommendations

Breastfeeding

Advice to breast feed if possible is included in the SIDS prevention programme in New Zealand, but is not mentioned in the UK Department of Health advice. Almost all studies show that breast feeding is associated with a reduced risk of SIDS.61 However, in countries such as the UK where breast feeding rates are low and strongly associated with socioeconomic status, adjustment for socioeconomic status decreases the level of protection, leading some authors to conclude that there is no reduced risk.16,62 However, the larger studies consistently show a reduced risk of SIDS with breast feeding even after adjustment for socioeconomic status.20,63,64,65 Breastfed infants have more arousals than bottle‐fed infants, which may explain a possible protective effect.66 In addition, breast feeding reduces infection, which could also be the protective mechanism.67

Even if the recommendation to breast feed is not included in the specific SIDS prevention advice, it should be included in the general advice, as it reduces morbidity and mortality in infants even in developed countries.9

Pacifiers (dummies)

For several years now, The Netherlands has recommended the use of pacifiers in bottle‐fed infants. In October 2005, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended the use of a pacifier throughout the first year of life. Two recent meta‐analyses have shown that pacifier use in the last sleep is associated with a reduced risk of SIDS.68,69 Hauck et al68 recommended pacifier use up to 1 year of age. Concerns about possible adverse effects, especially on breastfeeding, and an increase in otitis media, led the other review69 to recommend that pacifier use should not be discouraged, but not specifically recommended.

Conclusions

The wording of the Department of Health recommendations for SIDS prevention has changed over the past 6 years, but the specific recommendations are largely consistent with the scientific evidence. Two major recommendations need to be discussed in greater detail: (1) breastfeeding and (2) pacifier use. The evidence that breastfeeding is protective is consistent in the larger studies and there is a plausible biological mechanism. Breastfeeding rates in the UK are poor, and thus the proportion of SIDS that might be attributable to bottle feeding is high. Although sleeping in the parent's bedroom is implied in the recommendation “The safest place for your baby to sleep is in a cot in your room for the first six months of life”, this needs to be made more explicit.

General practitioners and health visitors provide advice to parents. They have access to the Department of Health recommendations, but have to go to the original literature to find the evidence supporting these recommendations. Meta‐analyses or reviews looking at each risk factor in turn are required, as has been done recently with pacifiers and SIDS, and previously with prone sleeping position and SIDS. Further, the establishment of a committee that reviews the recommendations and publishes the evidence that leads to these recommendations, as is done by the American Academy of Pediatrics Taskforce on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, is required.

Although mortality due to SIDS has decreased, application of current knowledge is predicted to reduce SIDS further.

Abbreviations

ICD - International Classification of Diseases

SIDS - sudden infant death syndrome

SUDI - sudden unexpected death in infants

Footnotes

Funding: EAM is supported by the Child Health Research Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Department of Health Department of Health issues new advice on cot death, 2000. http://www.dh.gov.uk (accessed 2 Nov 2006)

- 2.Department of Health Reduce the risk of cot death: an easy guide, 2004. http://www.dh.gov.uk (accessed 2 Nov 2006)

- 3.Department of Health Reduce the risk of cot death: an easy guide, 2005. http://www.dh.gov.uk (accessed 2 Nov2006)

- 4.Kattwinkel J, Brooks J, Myerberg D. Positioning and SIDS. AAP Task Force on infant positioning and SIDS. Pediatrics 1992891120–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on infant sleep position and sudden infant death syndrome. Changing concepts of sudden infant death syndrome: implications for infant sleeping environment and sleep position, Pediatrics 2000105650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on sudden infant death syndrome. The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome: diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk, Pediatrics 20051161245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braiker B. A quiet revolt against the rules on SIDS. The New York Times 18 October 2005

- 8.Foundation for the Study of Infant Death What is cot death? http://www.sids.org.uk/fsid/cot.htm (accessed 2 Nov 2006)

- 9.Kovar M G, Serdula M K, Marks J S.et al Review of the epidemiologic evidence for an association between infant feeding and infant health. Pediatrics 198474615–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Impact of vaccines universally recommended for children—United States, 1990–1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 199948243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell E A. Cot death: should the prone sleeping position be discouraged? J Paediatr Child Health 199127319–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beal S M, Finch C F. An overview of retrospective case‐control studies investigating the relationship between prone sleeping position and SIDS. J Paediatr Child Health 199127334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponsonby A L, Dwyer T, Cochrane J. Population trends in sudden infant death syndrome. Semin Perinatol 200226296–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willinger M, Hoffman H J, Hartford R B. Infant sleep position and risk for sudden infant death syndrome: report of meeting held January 13 and 14, 1994, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. Pediatrics 199493814–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scragg R K R, Mitchell E A. Side sleeping position and bed sharing in the sudden infant death syndrome. Ann Med 199830345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming P J, Blair P S, Bacon C.et al Environment of infants during sleep and risk of the sudden infant death syndrome: results of 1993–5 case‐control study for confidential inquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy. BMJ 1996313191–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oyen N, Markestad T, Skaerven R.et al Combined effects of sleeping position and prenatal risk factors in sudden infant death syndrome: the Nordic Epidemiological SIDS Study. Pediatrics 1997100613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D K, Petitti D B, Willinger M.et al Infant sleeping position and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in California, 1997–2000. Am J Epidemiol 2003157446–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carpenter R G, Irgens L M, Blair P S.et al Sudden unexplained infant death in 20 regions in Europe: case control study. Lancet 2004363185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vennemann M M, Findeisen M, Butterfass‐Bahloul T.et al Modifiable risk factors for SIDS in Germany: results of GeSID. Acta Paediat 200594655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell E A. Smoking: the next major and modifiable risk factor. In: Rognum TO, ed. Sudden infant death syndrome. New trends for the nineties. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, 1995114–118.

- 22.Golding J. Sudden infant death syndrome and parental smoking—a literature review. Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol 19971167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson H R, Cook D G. Passive smoking and sudden infant death syndrome: review of the epidemiological evidence. Thorax 1997521003–9 erratum in 19993656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell E A, Milerad J. Smoking and sudden infant death syndrome. Rev Environ Health 20062181–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Windham G C, Eaton A, Hopkins B. Evidence for an association between environmental tobacco smoke exposure and birthweight: a meta‐analysis and new data. Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol 19991335–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiers P S. Disentangling the separate effects of prenatal and postnatal smoking on the risk of SIDS. Am J Epidemiol 1999149603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klonoff‐Cohen H S, Edelstein S L, Lefkowitz E S.et al The effect of passive smoking and tobacco exposure through breast milk on sudden infant death syndrome. JAMA 1995273795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alm B, Milerad J, Wennergren G.et al A case‐control study of smoking and sudden infant death syndrome in the Scandinavian countries, 1992–1995. Arch Dis Child 199878329–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell E A, Ford R P, Stewart A W.et al Smoking and the sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics 199391893–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blair P S, Fleming P J, Bensley D.et al Smoking and the sudden infant death syndrome: results from 1993–5 case‐control study for the confidential inquiry into stillbirths and death in infancy. BMJ 1996313195–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleming P J, Gilbert R, Azaz Y.et al Interaction between bedding and sleeping position in the sudden infant death syndrome: a population based case‐control study. BMJ 199030185–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert R, Rudd P, Berry P J.et al Combined effect of infection and heavy wrapping on the risk of sudden unexpected infant death. Arch Dis Child 199267171–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponsonby A L, Dwyer T, Gibbons L E.et al Factors potentiating the risk of sudden infant death syndrome associated with the prone position. N Engl J Med 1993329377–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams S M, Taylor B J, Mitchell E A. Sudden infant death syndrome: insulation from bedding and clothing and its effect modifiers. Int J Epidemiol 199625366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vennemann M M T, Findeisen M, Butterfaß‐Bahloul T.et al Infection, health problems and health care utilization and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Arch Dis Child 200590520–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.L'Hoir M P, Engelberts A C, van Well G T J.et al Risk and preventive factors for cot death in Netherlands, a low‐incidence country. Eur J Pediatr 1998157681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ponsonby A L, Dwyer T, Couper D.et al Association between use of a quilt and sudden infant death syndrome: case–control study. BMJ 1998316195–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleemann W J, Schlaud M, Fieguth A.et al Body and head position, covering of the head by bedding and risk of sudden infant death (SID). Int J Legal Med 199911222–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beal S M. Sudden infant death syndrome in South Australia 1968–97. Part I: changes over time. J Paediatr Child Health 200036540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scragg R, Mitchell E A, Taylor B J.et al Bedsharing, smoking and alcohol in the sudden infant death syndrome: results from the New Zealand cot death study. BMJ 19933071312–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hauck F R, Herman S M, Donovan M.et al Sleep environment and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in an urban population: the Chicago Infant Mortality Study. Pediatrics 20031111207–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tappin D, Ecob R, Brooke H. Bedsharing, roomsharing, and sudden infant death syndrome in Scotland: a case‐control study. J Pediatr 200514732–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blair P S, Fleming P J, Smith I J.et al Babies sleeping with parents: case‐control study of factors influencing the risk of the sudden infant death syndrome. BMJ 19993191457–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGarvey C, McDonnell M, Chong A.et al Factors relating to the infant's last sleep environment in sudden infant death syndrome in the Republic of Ireland. Arch Dis Child 2003881058–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carpenter R G. The hazards of bed sharing. Paediatr Child Health 200611(Suppl A)24A–28A. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blair P. SIDS epidemiology and bed sharing. Paediatr Child Health 200611(Suppl A)29A–31A. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosko S, Richard C, McKenna J. Infant arousals during mother‐infant bed sharing: implications for infant sleep and sudden infant death syndrome research. Pediatrics 1997100841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phillipson E A, Sullivan C E. Arousal: the forgotten response to respiratory stimuli. Am Rev Respir Dis 1978118807–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scragg R K R, Mitchell E A, Stewart A W.et al Infant room sharing and prone sleeping position in the sudden infant death syndrome. Lancet 19963477–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ford R P K, Mitchell E A, Stewart A W.et al SIDS, illness, and acute medical care. Arch Dis Child 19977754–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ministry of Health Well Child Tamariki Ora Health Book. Child sickness danger signs. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2005, http://www.healthed.govt.nz/upload/PDF/7012.pdf (accessed 13 Nov 2006)

- 52.Jonville‐Bera A P, Autret‐Leca E, Barbeillon F.et al Sudden unexpected death in infants under 3 months of age and immunisation status—a case‐control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 200151271–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von Kries R, Toschke A M, Strassburger K.et al Sudden and unexpected deaths after the administration of hexavalent vaccines (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, hepatitis B, Haemophilius influenzae type b): is there a signal? Eur J Pediatr 2005 200516461–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fleming P J, Blair P S, Platt M W.et al The UK accelerated immunisation programme and sudden unexpected death in infancy: case‐control study. BMJ 2001322822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Griffin M R, Ray W A, Livengood J R.et al Risk of sudden infant death syndrome after immunization with the diphtheria‐tetanus‐pertussis vaccine. N Engl J Med 1988319618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoffman H J, Hunter J C, Damus K.et al Diphtheria‐tetanus‐pertussis immunization and sudden infant death: results of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Cooperative Epidemiological Study of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome risk factors. Pediatrics 198779598–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitchell E A, Stewart A W, Clements M. Immunisation and the sudden infant death syndrome. New Zealand Cot Death Study Group. Arch Dis Child 199573498–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scheers N J, Dayton C M, Kemp J S. Sudden infant death with external airways covered: case‐comparison study of 206 deaths in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998152540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson C A, Taylor B J, Laing R M.et al Clothing and bedding and its relevance to sudden infant death syndrome: further results from the New Zealand Cot Death Study. J Paediatr Child Health 199430506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mitchell E A, Williams S M, Taylor B J. Use of duvets and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Arch Dis Child 199981117–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McVea K L, Turner P D, Peppler D K. The role of breastfeeding in sudden infant death syndrome. J Hum Lact 20001613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gilbert R E, Wigfield R E, Fleming P J.et al Bottle feeding and the sudden infant death syndrome. BMJ 199531088–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoffman H J, Damus K, Hillman L.et al Risk factors for SIDS. Results of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development SIDS Cooperative Epidemiological Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 198853313–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ford R P K, Taylor B J, Mitchell E A.et al Breastfeeding and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Int J Epidemiol 199322885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alm B, Wennergren G, Norvenius S G.et al Breast feeding and the sudden infant death syndrome in Scandinavia, 1992–95. Arch Dis Child 200286400–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Horne R S, Parslow P M, Ferens D.et al Comparison of evoked arousability in breast and formula fed infants. Arch Dis Child 20048922–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Howie P W. Protective effect of breastfeeding against infection in the first and second six months of life. Adv Exp Med Biol 2002503141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hauck F R, Omojokum O O, Siadaty M S. Do pacifiers reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome? A meta‐analysis. Pediatrics 2005116e716–e723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitchell E A, Blair P S, L'Hoir M P. Should pacifiers be recommended to prevent SIDS? Pediatrics 20061171755–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]