Abstract

Objectives

To understand lay views on infant size and growth and their implications for a British population.

Methods

A systematic review of parental and other lay views about the meanings and importance of infant size and growth using Medline, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, IBSS, ASSIA, British Nursing Index ChildData, Caredata, SIGLE, Dissertation Abstracts (US), Index to Theses. 19 studies, most of which reported the views of mothers, from the US, Canada, the UK and Finland were reviewed.

Results

Notions of healthy size and growth were dominated by the concept of normality. Participants created norms by assessing and comparing size and growth against several reference points. When size or growth differed from these norms, explanations were sought for factors that would account for this difference. When no plausible explanation could be found, growth or size became a worry for parents.

Conclusions

Parents consider the importance of contextual factors when judging what is appropriate or healthy growth. For public health advice to be effective, lay, as well as scientific, findings and values need to be considered.

Growth and size in infancy matter to parents and professionals. Intervention in infancy has the potential to promote health throughout the life course.1 Although the benefits (or otherwise) of early interventions may not be realised for many years, the beliefs and behaviours of individual lay persons (in this case, particularly parents) will affect the uptake of policy or interventions immediately. As Harden et al2 point out, bringing together views and studies in a systematic way may deepen our understanding of public health issues. Systematic reviews also represent good stewardship in terms of the time of both participants and researchers.

This paper describes a systematic review designed to understand lay (particularly parental) views of infant size and growth.

Methods

This research was part of a review of scientific evidence on infant growth and health, which included a review of the relationship between infant growth or size and life‐course outcomes.3,4,5

Combining quantitative and qualitative research in systematic reviews is a developing method.6,7 Techniques currently used in such reviews,8,9 alongside guidance from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination,10 were used in this review, including independent double reviewing at all stages.

Twelve databases were searched (Medline, PsycInfo, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, IBSS, ASSIA, British Nursing Index, ChildData, Caredata, SIGLE, Dissertation Abstracts (US), Index to Theses). The table in the appendix provides search terms, which include terms for size, weight or growth and qualitative methods, views, and opinions or attitudes. Searches were conducted in August 2003 and updated in March 2004 (2852 abstracts retrieved and screened). Subject experts and corresponding authors of included papers were contacted for details of additional studies.

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Age: views towards infants aged 0–24 months (including retrospective accounts)

Publication date: since 1978 (one generation)

Study focus: opinions, views and attitudes on size or growth of infants

Methods: qualitative and quantitative studies, including survey of views but excluding studies of food intake alone

Country: no countries were excluded a priori, reviewers considered relevance of each study to a British context.

Data extraction was challenging for quality assessment and extraction of findings across different study designs. We resolved this problem by extracting data as relevant to this review. Study quality was assessed using a revised checklist for qualitative research.6,11,12 Quality was judged on appropriateness of design, the extent to which context and setting were accounted for, appropriateness of sampling strategy, participation or response rates, the process of analysis (including triangulation), assessments made of typicality and indication of relevance to policy. Harden et al2 have suggested that studies not “rooted” in the experience of the individual should be excluded from systematic reviews of views. We did not exclude, but instead reported, quality assessments alongside study descriptions, and embedded quality assessment in the data extraction process. Reviewers distinguished between directly reported views and author interpretations or quantitative summaries; greater weight was placed on the directly reported views.

Study findings were extracted using the following questions:

What is healthy size and growth?

How important are size and growth to participants?

What concepts are used to define healthy size and growth?

How do participants assess normal size and growth?

Where does growth lie among priorities for health?

What information influences views and behaviour?

Who influences views and behaviour?

Two researchers independently conducted thematic analyses, categorising and interpreting extracted data. Relevance, strength and duplication of themes were discussed iteratively until an agreed synthesis was produced that allowed interpretation of all data.

Results

Overview

Nineteen studies (17 papers) were included, representing the views of 3590 individuals from the UK, Canada, Finland and the US. Most of the respondents were mothers (n = 1948), including 276 recruited at the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) clinics for low‐income families in the US and 212 mothers recruited because their child was born early, had been admitted to neonatal intensive care or had faltering growth. The sample also included 10 other family members, 16 dieticians, 263 public health nurses, 816 adults from general population samples and 730 children and adolescents (in one study).13,14

For the purposes of this review, reviewers judged the quality of many studies as low. Few studies reported qualitative data. Table 1 summarises the characteristics and quality appraisal of included studies.

Table 1 Descriptions and summarised appraisal of included studies.

| Study | Participants Location Design | Aims (where possible verbatim) Appraisal of methods | Infant age Participation rate Attributable quotations | Setting Sampling Triangulation used | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baughcum et al,15 1998 | 16 dieticians, 6 WIC mothers, 8 teenage WIC mothers | “To identify maternal beliefs and practices about child feeding that are associated with the development of childhood obesity” | 12–36 months old | WIC clinic and WIC nurses | Mothers were not concerned about overweight in their children. This was perceived as a problem by dieticians and study authors |

| Kentucky, USA | Design allowed for exploration of subjective experience | Not stated for mothers, 95% for dieticians | Risk of bias as sampling restricted to health clinic users | ||

| Qualitative (focus groups) | not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Baughcum et al,16 2001 | 454 mothers, 258 attending WIC and 196 attending private child health clinics | “To determine if the factor scores [from questionnaire under development] were associated cross‐sectionally with (1) the child being overweight at the time of the survey (2) maternal obesity, and (3) lower socio‐economic status.” | 11–24 months, but considering retrospectively to first year | Health clinics (WIC or private) | Mothers were more concerned about under eating and underweight, although where children were overweight there was concern about overeating and overweight |

| Cincinnati and Kentucky, USA | Design did not allow exploration of subjective views | 98% | Risk of bias as sampling restricted to health clinic users | ||

| Quantitative attitudinal (closed questionnaire) | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Birgeneau,17 2001 | 229 adults (129 women, 100 men) | Several hypotheses described in Chapter 2, summarised in abstract as “the present study examined adult weight‐related biases applied to infants in a sample of . . . adults” | Sitting infants | Not clear, but sample largely drawn from university population | Fatter infants rated as less attractive and less sociable than average weight infants |

| Boston, USA | Design did not allow subjective views | Not stated | Reporting did not give adequate details | ||

| Quantitative attitudinal (Likert scales) | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Brown,18 1981 | 93 mothers | “To investigate parental concerns about infant physical and behaviour development during first 9 months of life” | 0–9 months | University of California at Los Angeles newborn nursery plus other hospitals | 5/20 parents of full‐term babies recorded growth as concern across all ages. Physical growth was an increasing concern across time for parents of preterm infants |

| Los Angeles, USA | Categorisations of interview data. Relatively little exploration of subjective experience | Not stated | Not stated | ||

| Quantitative data | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Hall et al,19 2002 | 60 mothers | “To compare differences in maternal confidence and competence in mothers of preterm infants who were weighed before and after breastfeeding throughout hospitalisation and those who were not weighed with breastfeeds” | Postpartum—4 weeks after discharge. | NICU | Test weighing during hospitalisation did not affect maternal competence or confidence in a short‐term intervention, but both confidence and competence increased over time for both groups. Important influences from their social network were noted |

| Canada | Design did not allow exploration of subjective views | 82% (7 lost to follow‐up, 4 excluded) | Sampling appropriate for this population | ||

| Quantitative attitudinal | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Hewatt and Ellis,20 1986 | 40 mothers who had breast fed for at least 2 days | To explore “women's perceptions of their breastfeeding experiences” | 9–13 months | Home based, after delivery in single maternity hospital | Differences between mothers who breastfed for shorter and longer duration were noted; those who breastfed for longer were more likely to disregard health professionals comments about underweight |

| Vancouver, Canada | Design allowed exploration of subjective experience | 80% | Restricted to those who intended to breast feed, and criteria used for purposive element not clear | ||

| Qualitative (interviews) | Not attributable to individuals | Three interviewers used, who met regularly. Background of interviewers unknown and use of meetings not stated | |||

| Kramer et al,21 1983 | 50 mothers | To determine the importance of factors affecting obesity in the first 2 years of life | Newborn | Single hospital maternity ward | Older mothers and those with higher socio‐economic status were more likely to prefer leaner infants. No associations were found between preferences for body sizes and attitudes to feeding |

| Montreal, Canada | Design allowed limited exploration of subjective experience | 100% | Sampling not described in full, potential bias as consecutive births of full term, healthy hospital‐delivered infants | ||

| Quantitative (psychometric assessment tool) | Not attributable to individuals | Results from two questionnaires (both numerical) were compared | |||

| May,22 1997 | 14 mothers of infants admitted to NICU | “What is the process mothers use to seek help when providing care to low birth weight infants at home?” | Mean 9 months, range 4–12 months | Home based, after admission to NICU | Mothers were concerned that babies should be ‘normal', compared with other babies, and monitored for signs of progress |

| USA | Design allowed exploration of subjective experience | Not stated | Good sampling for this population | ||

| Qualitative (semistructured interviews) | Identified by interview number | Triangulation used as well as inquiry audit, peer debriefing and reflexive journal | |||

| McCann et al,23 1994 | 26 mothers of children with poor weight gain | “To determine whether disturbed eating habits and attitudes to body shape, weight, and food are more common among mothers of children with non‐organic failure to thrive than among mothers from the general population.” | Mean age 3.8, range 0.9–9.6 years considering previous experience | Purposive sample from one region of UK | Mothers were concerned about possibility of underlying organic causes of poor growth. Some mothers restricted intake of food they viewed as unhealthy |

| Oxfordshire, UK | Design may allow exploration of subjective experience, but interview methodology not clear | Not stated | Recruitment methods not stated | ||

| Quantitative (psychometric assessment tool) and qualitative (interview) | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Pridham*,24 1984 | 62 mothers | “To explore mothers' specification and description of issues on which they are working and the nature of the infant care task and the types of help and stress/support they experienced.” | 0–90 days | Single health clinic | Data reduced substantially in reporting, eg, 10 000 logged problems reduced to 7 categories. Mothers sought help from books, relatives, partners and friends. Most common problems were never mentioned to a healthcare professional |

| Madison, USA | Categorisations of participant's diary and log. Little exploration of subjective experience | Not stated | Sample restricted to participants at university department teaching clinic | ||

| Quantitative | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Pridham*,24 1984 | 22 mothers | “To examine the types of goals and decision‐making rules that mothers applied to 2 simulated infant care problems.” | 0–90 days | Single health clinic | Grandparents were the most commonly used source of information. Mothers' problem solving behaviour conformed to other models of problem solving by lay people |

| Madison, USA | Categorisations of telephone interview. Little exploration of subjective experience | Not stated | Sample restricted to participants at university department teaching clinic | ||

| Quantitative | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Rand and Wright†,13,14 2000, 2001 | 1317 (303 elementary school children; 427 high school adolescents; 261 university students; 326 middle‐age adults) | Paper one: an “evaluation of ideal and acceptable body sizes across a wide subject age span” | Sitting up babies | Varied settings in one region of USA | Preference for mid‐range body size across groups. A wider range of sizes was seen as acceptable in infants than in older children |

| Appalachia, USA | Paper two: “to examine the possibility of a more restrictive standard for females than males across a wide age span” | Not stated | Recruitment not described, except that university students gained credit points for taking part | ||

| Quantitative attitudinal. (Likert scales) | Design did not allow exploration of subjective views | Not attributable to individuals | Some triangulation, in that different groups responses to the same question are compared | ||

| Rajan and Oakley,25 1990 | 467 mothers | “We are concerned with . . . how the women themselves felt abut having a small baby, why they thought it happened, and how it had affected their life” | 6 weeks | Participants own homes | Different experiences presented. “Two thirds of all women did not see low birth weight as a problem in itself”, instead many thought that “prematurity, rather than low birth weight alone, was the major problem”. Where support was available to mothers from family or health professionals it was seen as vital |

| Midlands and South of England, UK | Qualitative (postal questionnaire with some open‐ended questions). Design allows exploration of subjective experience | 94% | Sample taken from previous study, of new mothers who had previously had a low birthweight baby | ||

| Qualitative (postal questionnaire with some open ended questions) | Yes, brief descriptions of participants | Somewhat. Statistical and some qualitative data (generated from open‐ended questionnaire) presented, and previous study referred to, but not different points of view | |||

| Reifsinder et al,26 2000 | 22 low‐income mothers (WIC) (13 with previous children with faltering growth) | “What are the explanatory models of growth held by mothers of growth‐deficient children?” | Age range 22.5–51 months, considering growth in previous 2 years | Data collection took place in participants own homes, but all data collected by nurses | Mothers were concerned about growth and assessed it through growth measurements, clothing sizes and comparisons to other children. Although size and growth were important, mothers viewed them as “natural phenomena” that were unproblematic when other factors (feeding, care taking, inherited characteristics) were accounted for |

| Texas, USA | Design allows exploration of subjective experience | 56% | Participants recruited from previous research with WIC mothers. | ||

| Qualitative (interviews) | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Sherratt et al,27 1991 | 228 mothers (113 of high‐risk infants, 115 low‐risk infants) | “Sought parents' views on the available services and compared the concerns of parents of six‐month old infants who had been at high risk neonatally with those of parents whose infants did not have these risk factors” | 6 months | Participants own homes | Lack of concern about growth patterns and overall developmental progress in both groups. However, child health clinics were ‘overwhelmingly perceived as places to weigh babies'. No tests of significance performed. |

| Buckinghamshire, UK | Design offered limited exploration of subjective views | 88% | Recruited from hospital nursery and health visitor records, appropriate for sample of health service users | ||

| Quantitative attitudinal (questionnaire, closed questions) | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Smith,28 1989 | 41 parents (possibly all mothers) 19 primaparae, 22 multiparae. | “The purpose of this study was to determine the major concerns of primiparae and multiparae 1 month post‐delivery and the resources used in meeting identified concerns.” | Contacted 4 weeks postpartum but return dates not stated | Single large maternity hospital | 32 categories of concerns, in which growth and development came 15th, with 7/19 primaparae and 6/22 multiparae including growth among concerns. Sources of help identified; partners, pamphlets, books, help from health professionals more common in primaparae |

| Vancouver, Canada | Design likely to offer limited exploration of subjective views | 68% for postal survey, not stated for recruitment by ward. | Appropriate to recruit English speaking mothers of healthy babies after spontaneous vaginal delivery in hospital | ||

| Quantitative attitudinal (questionnaire) | Not attributable to individuals | Not stated | |||

| Sturm et al,29 1997 | 132 mothers (50 with babies with faltering growth) | “Tested for defensive bias in mothers' causal attributions for infant (2–12.5 months) growth deficiency” | 2–12.5 months | Participants at health clinic or outpatients. Data collection took place in waiting rooms which may have created bias in responses | Findings difficult to use because responses to individual questions were not reported. Mothers seemed to place most weight on medical explanations of their child's growth |

| Location of study not stated, assumed USA | Design did not allow exploration of subjective views | Not stated | Restricted to users of healthcare services | ||

| Quantitative attitudinal. (Likert scales) | Not attributable to individuals | Some, inasmuch as different groups of mothers to same questions, but no differences in interpretation of results. | |||

| Thomlinson,30 2002 | 12 families (including 21 participants: 11 mothers, 1 stepmother, 6 fathers, 3 grandmothers). | To explore the experience of families with children who were failing to thrive; aim was not to generalise but to generate a rich description of the phenomenon of living with children who were not growing as expected | Not stated, asked for retrospective account | Participants' homes | Anxiety among family members when children had very poor growth strongly linked to anxiety about the health of the child |

| Canada | Design allows exploration of subjective experience | Not stated | Sampling appropriate for this population | ||

| Qualitative (interviews) | Not attributable to individuals | Yes, different family members were spoken to, although no input from other researchers/analysts | |||

| Vehvilainen‐Julkunen,31 1994 | 263 Public health nurses working in primary care and 323 of their clients | “The following two question were addressed | Age not stated, but still under care of nurses after birth | Very wide geographical area | Nurses interpreted function of home visits as providing support and encouragement for parents. For parents the most important function of the home visits related to the examination of the newborn including weighing |

| Finland | How do public health nurses and clients describe the options they have with regard to home visits? | 87% of eligible nurses, not stated for patients | Random sample of all public health nurses working in prenatal and child welfare clinics. Nurses sent out questionnaires to last three clients, which may have introduced selection bias | ||

| Quantitative attitudinal (questionnaire) | How do public health nurses and clients describe the functions and meanings of home visits?” | Not attributable to individuals | Not in terms of analysis or interpretation, although client and nurse views compared | ||

| Design likely to offer limited exploration of subjective views |

NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children.

*Two studies were presented in this paper and are described separately here.

†A single study was described across these papers.

Despite our efforts to find studies elsewhere, all were from the discipline of healthcare, and were often conducted in primary care, by nurses or with mothers of infants with health problems.

Size or growth?

Size and growth have precise and different meanings. However, neither authors nor participants made this distinction explicit. For consistency, we have tended to refer to size alone, except in referring to growth monitoring and faltering growth.

Understanding healthy size

Notions of healthy size were dominated by constructions of normality; “normal” size and development was key for many parents, particularly parents of low birthweight infants.22

Constructing size norms

Seven studies reported data on how participants assessed or defined normal size.13,14,15,22,26,27,30,31 Four themes emerged with regard to assessment of size:

Medical definitions, including the use of growth charts.26,27,31 “I take her to clinic where they measure her height and her weight. They show me ... what is the normal height for children her age” (WIC mother).26

Comparisons with other children in the community.13,14,22,30 “You just want him to be normal, like everyone else” (mother).30

Comparison with family members.15,26 “She's just a little below average as far as the children in the family” (WIC mother).26

Use of clothing sizes. “If they are not fitting in the clothes they should be fitting in, they're not average” (WIC mother).26

Explaining size difference

Participants sought explanations for size that differed from normal, including the following:

Inherited differences.15 “I really do believe it is genes”.26

Medical explanations, in studies considering children with poor growth.15,18,23,29,30

Quality of care.15,26 “The care, the diet, parents having a lot of love toward their children makes them grow” (WIC mother).26

Fatalism: sometimes implicit (eg, heritability) and explicit in one study: “I think that her size is out of my hands” (WIC mother).26

Concerns about size

Participants associated size with health.23,30 “Unhealthy” size indicated that something was wrong: “we were panicked, we knew something was wrong”.30 Despite this, size itself was not the most important concern, even for parents of small infants.22,25 “As my daughter was healthy and full‐term, I felt too much was made of her weight. If she was having trouble with her breathing, I could understand the concern” (mother, dispenser in pharmacy).25

Participants and study authors viewed feeding and size as complementary15,26,21,23: “If [my children] are overweight, at least I know they're eating”.15 Conversely, if infants were appropriately fed, parents were less likely to be concerned about size. Mothers were more concerned about undereating and avoiding hunger in infants.16

Other concerns included infant attractiveness and ease of birth of smaller infants.17,25

Nutritional status of infants was also important. Authors in one study noted half of mothers of children with faltering growth restricted intake of unhealthy food.23

Size was also a marker of parental competence. Mothers “reported blaming themselves for their child's poor weight gain, feeling they had not done sufficient to ensure adequate weight gain.”23 Experience seemed to increase confidence in parents of premature infants.19

Level of concern about size

Despite low levels of concern about size,18 a high value was placed on growth monitoring.27,31 In one study, 85–92% of mothers gave weighing their infant as the most common reason to attend a clinic.27

In a phenomenological study on parents of children with faltering growth, the lack of explanation for growth differences provoked anxiety: “The constant fear with which families lived was all encompassing”.30

Influence on views, behaviour and interpretations of size

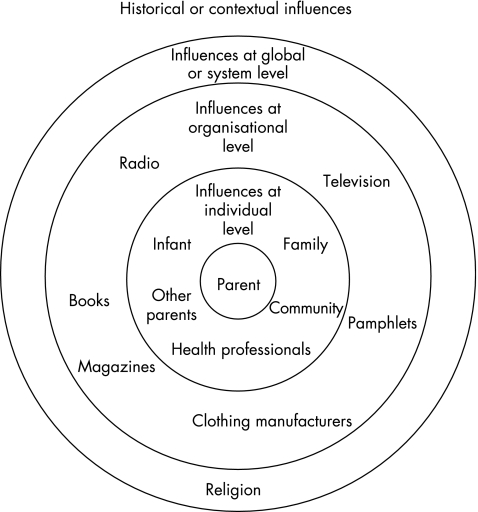

Figure 1 (from Brofenbrenner32) shows the influences as organised by reviewers into a nested model.

Figure 1 Influences on views and behaviour (from Bronfenbrenner32).

Mothers listened to advice and information from close family and friends.15,18 Wider social networks (relatives and other parents) also influenced mothers,22 but were not always welcome25: “it was so difficult to go out and hear negative things about him...” (mother of child with faltering growth).30

Mothers also listened to health professionals.23 In a study on midwife support, one mother said of the research midwife: “This kind of support should be available to all women” (barmaid).25 First‐time mothers used health professionals more than those with older children.28

Health professionals could also have a negative effect on women's feelings20: “Frequent weight checks and visits from health visitors [were] constant reminders of maternal inadequacy in producing a baby that was different from ‘normal'”.30 Lack of information from health professionals was frustrating: “I just see them writing down [his weight and height] ... They don't tell me how much he has grown” (WIC mother).26

Other sources used by participants were pamphlets,28 books,24 magazines, television and radio.27

The studies were reported between 1981 and 2002. None described their historical or cultural context.

Discussion

Principal findings

Notions of what constituted healthy size were dominated by the concept of “normality” reflected in concerns about size, sensitivity to the comments of others and distress when no plausible explanation for size difference could be found.

The data have some contradictions—for example, the contrast between the importance ascribed to growth monitoring and the value given to size alone as a measure of health. Parents may be using growth as a means of assessing unobservable characteristics (eg, good parenting or adequate nourishment). These contradictions may also be due to the limitations of included studies or may reflect inconsistencies in how people understand everyday life.

In contrast with the wish for “normality”, for some there was an optimistic feeling that children were simply going to be the size that they were going to be. Provided infants were well cared for, size was not something to worry about. More powerful than fatalistic notions was the concept of appropriate individual variation. This is important when considering how health professionals communicate concerns about size or growth to parents.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

An advisory group with backgrounds in public health, paediatrics, infant nutrition, qualitative and quantitative methods, systematic reviewing and including user groups oversaw the study. In attempting to locate and synthesise studies, a wide range of sources was searched. However, the relatively well‐developed systems for searching health databases may have contributed to the dominance of studies concerned with health.

Although we restricted the included studies to those from countries that are socially or economically similar to the UK, or which have contributed a large immigrant community to the UK, the studies were largely based outside the UK. Applicability to the UK population or healthcare system would need to be tested.

Research paradigms tend to favour studies of single systems, diseases or social constructs. This can result in a focus on “problematic” individuals, as observed in the included studies. Gaps in the research literature included the views of family members other than mothers (particularly fathers), and comparisons between the views of those who have breast fed, bottle fed or weaned their infants; parents of first or subsequent infants, and of different ethnic or cultural groups. There was a paucity of high‐quality qualitative studies, and of studies combining qualitative and quantitative data.

To our knowledge, no reviews of views on early growth have been conducted. Two recent UK studies have commented on parents' perceptions of weight and overweight in young children,33,34 although neither included infants (and were therefore not included in this review).

Implications for clinicians and policy makers

The value placed by parents on being like everyone else has implications for health promotion messages. If trends in infant size continue towards greater fatness, “being normal” will include infants who are fatter than those in the past. Conversely, current concern about levels of overweight and obesity may lead to greater awareness and anxiety. The sensitivity of parents to such messages needs to be considered when disseminating research findings about changing norms.

This synthesis suggests some of the routes by which parents are influenced. Policy informed by such research is likely to be more meaningful to parents than simple messages about average size and average effects.

What is already known on this topic

Size and growth in infancy matter to parents and clinicians.

The behaviour and views of those who care for babies also matters.

To date, no systematic reviews of views on early growth exist.

What this study adds

Notions of what constituted healthy size were dominated by the concept of normality.

Growth charts, comparison with others and clothes were used to judge whether growth or size was normal.

Participants considered variations in size between infants appropriate, but were worried when difference was not explained by genetics, medical causes or feeding practices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank our advisory group for their advice and Tammi Lempert for assistance with data extraction. We thank the experts and first authors of papers whom we contacted for their assistance.

Abbreviations

WIC - Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children

Footnotes

Funding: This project was funded by the Department of Health, London, UK.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Barker D J, Winter P D, Osmond C.et al Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet 19892577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harden A, Garcia J, Oliver S.et al Applying systematic review methods to studies of people's views: an example from public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458794–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baird J, Lucas P, Fisher D.et al Defining optimal infant growth for lifetime health: a systematic review of lay and scientific literature. http://www.mrc.soton.ac.uk/index.asp?page = 176 (accessed 17 Nov 2006)

- 4.Baird J, Fisher D, Lucas P.et al Being big or growing fast; a systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. BMJ 2005331929–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher D, Baird J, Payne L.et al Are infant size and growth related to burden of disease in adulthood? A systematic review of literature. Int J Epidemiol 2006351196–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popay J, Roen K, Sowden A.et al Guidance for the narrative synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data in systematic reviews of effectiveness. http://www.lancs.ac.uk/fass/projects/nssr/index.htm (accessed 17 Nov 2006)

- 7.Dixon‐Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D.et al Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 20051045–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas J, Harden A, Oakley A.et al Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews. BMJ 20043281010–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox K, Stevenson F, Britten N.et alA systematic review of communication between patients and health care professionals about medicine‐taking and prescribing. London: Medicines Partnership, 2004. www.npc.co.uk (accessed 23 November 2006)

- 10.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews, 4 2nd edn. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination 2001

- 11.Arai L, Roen K, Roberts H.et al It might work in Oklahoma but will it work in Oakhampton? What does the effectiveness literature on domestic smoke detectors tell us about context and implementation? Inj Prev 200511148–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Popay J, Rogers A, Williams G. Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qual Health Res 19988351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rand C S W, Wright B A. Continuity and change in the evaluation of ideal and acceptable body sizes across a wide age span. Int J Eat Disord 20002890–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rand C S W, Wright B A. Thinner females and heavier males: who says? A comparison of female to male ideal body sizes across a wide age span. Int J Eat Disord 20012945–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baughcum A E, Burklow K A, Deeks C M.et al Maternal feeding practices and childhood obesity: a focus group study of low‐income mothers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 19981521010–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baughcum A E, Powers S W, Johnson S B.et al Maternal feeding practices and beliefs and their relationships to overweight in early childhood. J Dev Behav Pediatr 200122391–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birgenaeu C T. Body image in infancy. Adult body weight‐related biases applied to infants [dissertation]. Boston, MA: Univeristy of Massachesetts, 2001

- 18.Brown M M. An exploration of parental concerns about preterms and full term infants during the first nine months of life [dissertation]. Los Angeles, CA: University of California, 1981

- 19.Hall W A, Shearer K, Mogan J.et al Weighing preterm infants before & after breastfeeding: does it increase maternal confidence and competence? MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 200227318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewat R J, Ellis D J. Similarities and differences between women who breastfeed for short and long duration. Midwifery 1986237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer M S, Barr R G, Leduc D G.et al Maternal psychological determinants of infant obesity. Development and testing of two new instruments. J Chronic Dis 198336329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.May K M. Searching for normalcy: mothers' caregiving for low birth weight infants. Pediatr Nurs 19972317–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCann J B, Stein A, Fairburn C G.et al Eating habits and attitudes of mothers of children with non‐organic failure to thrive. Arch Dis Child 199470234–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pridham K F. Information needs and problem solving behavior of parents of infants. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 198420125–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajan L, Oakley A. Low birth weight babies: the mother's point of view. Midwifery 1990673–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reifsnider E, Allan J, Percy M. Mothers' explanatory models of lack of child growth. Public Health Nurs 200017434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherratt F, Johnson A, Holmes S. Responding to parental concerns at the six‐month stage. Health Visit 19916484–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith M P. Postnatal concerns of mothers: an update. Midwifery 19895182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturm L A, Drotar D, Laing K.et al Mothers' beliefs about the causes of infant growth deficiency: is there attributional bias? J Pediatr Psychol 199722329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomlinson E H. The lived experience of families of children who are failing to thrive. J Adv Nurs 200239537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vehvilainen‐Julkunen K. The function of home visits in maternal and child welfare as evaluated by service providers and users. J Adv Nurs 199420672–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bronfenbrenner U. Developmental ecology through space and time: a future perspective. In: Moen P, Elder GH, Luscher K, eds. Examining lives in context: perspectives on the ecology of human development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1995619–647.

- 33.Jeffrey A N, Voss L D, Metcalf B S.et al Parents' awareness of overweight in themselves and their children: cross sectional study within a cohort (EarlyBird 21). BMJ 200533023–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carnell S, Edwards C, Croker H.et al Parental perceptions of overweight in 3–5 y olds. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 200529353–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.