Abstract

Evidence that childhood maltreatment is associated with emotional and behavioral problems throughout childhood suggests that maltreatment could lead to impaired academic performance in middle and high school. This article explores these effects using data on siblings. An index measure of the intensity of childhood maltreatment was included as a covariate in multivariate analyses of adolescents’ risk for school performance impairments. Family fixed effects were used to control for unobservables linked to family background and neighborhood effects. More intense childhood maltreatment was associated with greater probability of having a low GPA (P=0.001) and problems completing homework assignments (P=0.007). Associations between maltreatment intensity and adolescent school performance were not sensitive to model specification. Additional analyses suggested that maltreatment effects are moderated by cognitive deficits related to attention problems. The implications of these findings for educators and schools are discussed.

Keywords: human capital, productivity

1. Introduction

Childhood maltreatment potentially has major economic implications for U.S. schools and for their students. Even conservative estimates suggest that at least 8 percent of U.S. children experience sexual abuse before age 18, while 17 percent experience physical abuse, and 18 percent experience physical neglect (Flisher, Kramer, Hoven, Greenwald, Alegria, Bird, et al., 1997; Gorey & Leslie, 1997). Childhood maltreatment, and aversive parenting practices, in general, has the potential to delay the academic progress of students (Shonk & Cicchetti, 2001). It therefore has the potential to undermine schools’ ability to satisfy standards of school progress entailed in the No Child Left Behind legislation (U.S. Department of Education, 2005), putting them at risk for loss of federal funding. It also has the potential to adversely affect students' economic outcomes in adulthood, via its impact on achievement in middle and high school (Cawley, Heckman, & Vytlacil, 2001; Heckman & Rubinstein, 2001).

Although its potential impact is large, evidence of causal effects of maltreatment on children's longer term outcomes in school is generally lacking. The current state of evidence for a link between childhood maltreatment (physical and sexual abuse or neglect) and school performance is limited to negative associations between maltreatment and school performance. On average, children who are maltreated receive lower ratings of performance from their school teachers, score lower on cognitive assessments and standardized tests of academic achievement, obtain lower grades, and get suspended from school and retained in grade more frequently (Erickson, Egeland, & Pianta, 1989; Eckenrode, Laird, & Doris, 1993; Kurtz, Gaudin, Wodarski, & Howing, 1993; Kendall-Tackett & Eckenrode, 1996; Rowe & Eckenrode, 1999; Shonk & Cicchetti, 2001). Maltreated children are also prone to difficulty in forming new relationships with peers and adults and in adapting to norms of social behavior (Shields, Cicchetti & Ryan, 1994; Toth & Cicchetti, 1996). Although these examples of negative associations between maltreatment and school performance are suggestive of causal effects, they could be spuriously driven by unmeasured factors in families or neighborhoods that are themselves correlated with worse academic outcomes among children (Todd & Wolpin, 2003).

In addition, not much of the previous evidence linking childhood maltreatment to worse school performance generalizes well to older children in middle and high school and to children not already identified as needing services. Evidence of the impacts of maltreatment on academic performance in the general population of middle and high school students is needed to establish evidence of effects on schooling attainment in the general education population and on economic outcomes in adulthood.

Using a large dataset of U.S. adolescent sibling pairs, this study explores effects of maltreatment—neglect, physical aggression, and sexual abuse—on adolescents’ performance in middle and high school. First, the questions of how childhood maltreatment theoretically could negatively affect later school performance, and of how unobserved family background and neighborhood characteristics might influence ordinary least squares and fixed effects regression estimates of relationships between childhood maltreatment and later school performance, are discussed. Second, empirical estimates from models that controlled for observable and unobservable family and neighborhood characteristics are presented.

2. Theoretical background

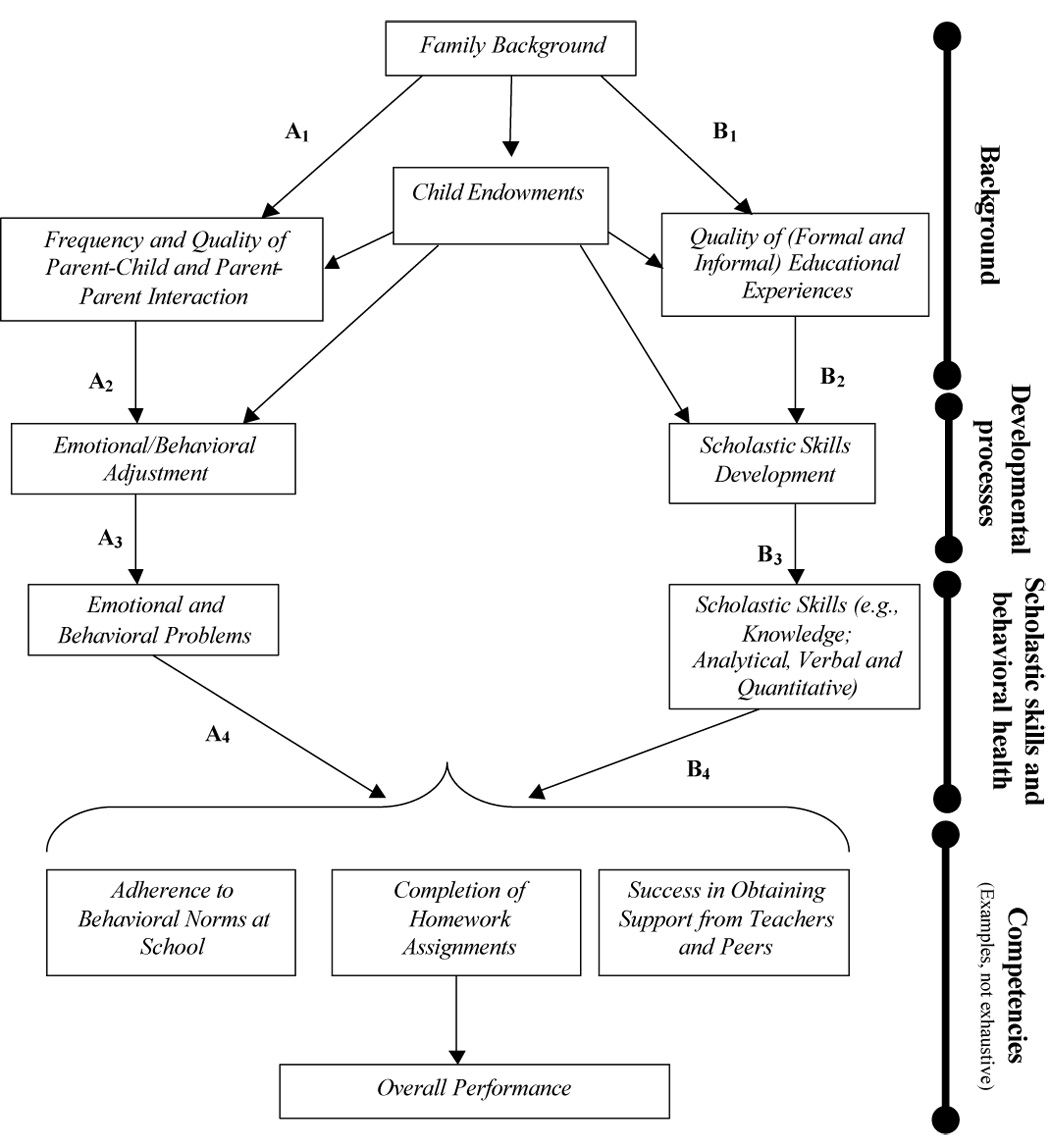

To motivate our empirical analyses, we developed a heuristic model that links childhood maltreatment with later academic performance deficits (Figure 1). The model is based on the idea, advocated by Shonk & Cicchetti (2001), that childhood maltreatment can influence children’s performance of competencies (e.g., engagement in academic tasks) that are necessary for optimal learning and achievement in school. At the top of Figure 1, family background affects the subsequent incidence of emotional and behavioral problems (Arrows A1, A2, and A3) through the effects of parent-child interactions (e.g., Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989; Ramey & Ramey, 2000), from childhood into adolescence (Costello, Angold & Keeler, 1999; Hofstra, Van der Ende & Verhulst, 2002). The influence of family background on development of conventional scholastic skills (Leibowitz, 1974), such as word knowledge, literacy, and quantitative reasoning, is represented separately (Arrows B1 to B4).

Figure 1.

Development and academic performance

Emotional and behavioral problems may result in impaired performance of competencies (Arrow A4), effects that operate either through learned interpersonal style (Belsky & Cassidy, 1994) or through cognitive and behavioral functions that are needed for optimal learning. For instance, children in households with frequent interpersonal conflict and physical, sexual, or other abuse may develop a heightened sensitivity to threats and a hostile pattern of response to perceived and actual threats from others (McGonigle, Smith, Benjamin, & Turner, 1993). Those children, in turn, could be more likely to behave in disruptive ways that increase their risk for out-of-school suspensions or other interruptions to classroom learning (Rapport, Denney, Chung, & Hustace, 2001). Emotional and behavioral problems may also result in cognitive impairments—greater concentration difficulties (Carlson & Kashani, 1988; Manly, Cicchetti, & Barnett, 1994); poorer motivation (Carlson & Kashani, 1988; Shonk & Cicchetti, 2001); impaired short-term memory (Lauer, Giordani, Boivin, Halle, Glasgow, Alessi, & Berent, 1994); or higher impulsivity and impaired executive function (Manly et al., 1994)—that result in reduced ability to perform well on school assignments and tests.

The model in Figure 1 also leaves room for several possible sources of unmeasured family or neighborhood influence. Childhood maltreatment could be more common in families that provide children with fewer tangible resources and less cognitive stimulation or in families less endowed genetically with aptitude for academic tasks (Arrows B1 to B4). Children living in emotionally strained households could be at greater risk for emotional and behavioral problems, and may also be more vulnerable to maltreatment (Arrows A1, A2, and A3). Neighborhood features provide a third set of unobservables. Schools offering a lower quality of education and worse learning environments could be more common in neighborhoods where maltreatment is more common.

3. Methods

3.1 Analyses

The empirical analyses were based on estimates from the multivariate cross-sectional regression model:

| (1) |

where Yij is a measure of scholastic performance for adolescent i residing in family j; X contains measures of family and individual background characteristics; M is a measure of maltreatment severity; Cij is a vector containing measures of acquired scholastic skills; β, δ, and λ are vectors of parameters estimated in the regression; ωj is an family-specific intercept for the school performance of adolescents in family j; and eij is a normally distributed individual-specific error term. Tests of the null hypothesis δ=0 were based on a student's t-test. All results were estimated with probability sample weights.

A known problem in obtaining unbiased reduced form estimates of δ in equation (1) is the potential influence of the unobserved family specific effect ωj. If ωj is correlated with independent variables in X or M, estimation of equation (1) by ordinary least squares regression will produce biased and inconsistent coefficient estimates (Wooldridge, 2002; pp. 247-251). Therefore, a second set of analyses used the "within" fixed effects estimator (Wooldridge, 2002), applied to siblings from the same family, to control for the unobserved average family effect, ωj, and thereby allowed for effects from net individual differences.

Once family effects are controlled, any remaining covariance between risk exposure and academic outcome can be interpreted as child-specific. If maltreatment experiences specific to a particular child are correlated with worse academic outcomes for that child, we can infer that maltreatment is a causal influence and/or that other child-specific risks for poor academic performance are correlated with the risk of being maltreated. Certain traits or characteristics of particular children—e.g., difficult behaviors or temperament—could drive aversive parent response as well as poorer academic performance.

Identification is a critical issue in our fixed effects analyses. The main identifying assumption of the estimator is that the incidence of maltreatment is to some extent idiosyncratic to particular children within a household. Several factors could result in variation of maltreatment experiences across children from the same family. First, ambiguities around pregnancy (whether was the child wanted and whether there was an extended separation of mother and child early in life) could initiate processes leading to greater difficulty between a particular child and a parent (Lynch, 1976). Second, a potential abuser may consider certain children either more or less vulnerable to abuse or more or less attractive targets for abuse (Finkelhor, 1994). Third, a child may remind a parent of a resented family member, such as a former partner, and this resentment may find expression in maltreatment of the child (Herrenkohl and Herrenkohl, 1979).

Concern that fixed estimates may be imprecise and biased in a relatively small sample (Wooldridge, 2002; p. 286) led us to also conduct analyses using the population average random effects estimation procedure. Though statistically efficient, the random effects estimator does not address the potential problem of omitted variable bias. Because we suspect that the incidence of other risk factors for poor performance in school may be positively correlated with maltreatment severity, we interpret the random effects estimates of δ as an upper-bound estimate of the true effect.

In each analysis, Hausman tests (Wooldridge, 2002; pp. 288-291) applied to the maltreatment coefficients in Model 1 were used to test for significant differences between the fixed effects and random effects coefficient estimates. Failure to reject the null of no differences suggests preference for the random effects estimates.

3.2 Data and sample selection

Data were drawn from the 1994–2002 National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). The Add Health data used here are from two waves: the Wave I baseline, which occurred during the 1994–1995 school year, and the Wave III follow-up conducted in 2001–2002. The Wave I Add Health core sample was designed to be representative of U.S. middle and high school students. Details of the sampling design are reported elsewhere (Harris, Florey, Tabor, Bearman, Jones, & Udry, 2003).

This study uses data on sibling pairs. In the Add Health, “siblings” are youths living in the same household. The Wave I core data included 2,014 unique sibling pairs. Due to attrition from the sample of either one or both siblings, 1,384 of the Wave I pairs (68.7%) survived in Wave III. Of these, missing information reduced to 958 the number of pairs with complete data. Approximately 7.4 percent (132) of these adolescents were matched in more than one sibling pair: 120 were in 2 pairs and 12 were in 3 pairs. We included all of these youths in our fixed effects analyses, even though they create an imbalance in the panel and could be a source of heteroskedasticity.

3.3 Measures

3.3.1 School performance impairments

Binary indicators were created for the sample quartile with the poorest school performance using four measures of performance: self-reported grade point average (GPA), getting along well with teachers and peers, completing homework assignments, and school attendance. Self-reported GPA’s are highly correlated with actual GPA reported in school records (Dornbusch, Ritter, & Leiderman, 1987). Low GPA corresponded to approximately a "C" average or worse. Not getting along with teachers and peers ("everyday" or "almost every day") is a proxy for low peer and teacher support; and not completing assignments ("everyday" or "almost every day") and poor attendance (8 or more days absent) are interpreted as measures of poor adherence to academic standards. The main reason for using indicators rather than continuous measures was that it made for an easier comparison of regression coefficients across measures of performance. Linear probability models were used for estimation.1 Coefficient estimates are marginal effects on the probability of impairment. We note that similar results were obtained using raw scales.

3.3.2 Maltreatment index

We constructed an index to serve as a scale measure of the potential for maltreatment to have negative psychological and developmental impacts. There is no consensus among psychologists about how maltreatment produces average effects (Barnett, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1993). We therefore were guided by theory and empirical evidence suggesting that subtype of maltreatment and subtype combination are important dimensions of potential for negative developmental impact (Barnett et al., 1993).

Wave III respondents (ages 18 to 26) reported on the frequency of specific types of events involving “parents or other adult care-givers” that occurred before the 6th grade. Items included – neglect of basic needs (e.g., “keeping you clean” or “providing food or clothing”), sexual contact (“touched you in a sexual way, forced you to touch him or her in a sexual way, or forced you to have sexual relations”), and physical aggression (“slapped, hit, or kicked you”). Respondents who reported no events of maltreatment of any type were assigned an index score of 0. One point was added to the index for maltreatment of any type, any sexual abuse, and >1 type of abuse, respectively.

3.3.3 Other independent variables

Several additional covariates were included in regressions: family income, parent marital status, parent educational attainment, race-ethnicity, child age, an indicator for low birthweight (<2,500 grams), a measure of achievement (the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Revised; PPVT), indicators for whether or not the child’s biological parents were present in the household, and gender.

4. Results

4.1 Sample description

Sample descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. Table 2 shows the relationship of the maltreatment index with dependent variables used in regression analyses. The maltreatment index was significantly associated with low GPA, problems completing homework assignments, and was marginally associated with being frequently absent from school. There was nonlinear (inverted U-shaped) relationship between maltreatment and problems with teachers and peers.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Mean | S.D. | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.519 | 0.018 |

| Age (years) | 15.474 | 0.060 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 0.717 | 0.015 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.134 | 0.011 |

| Hispanic | 0.080 | 0.009 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 0.070 | 0.008 |

| Family Income ÷ 10,000 | 4.311 | 0.148 |

| Low birthweight (1 if < 2.5 kg at birth) | 0.090 | 0.009 |

| Birth parents living with youth | ||

| Both mother and father | 0.605 | 0.016 |

| Mother only | 0.235 | 0.014 |

| Father only | 0.022 | 0.004 |

| Neither | 0.020 | 0.004 |

| Not reported | 0.120 | 0.011 |

| Mother's educational attainment | ||

| Did not complete high school | 0.129 | 0.013 |

| Completed high school | 0.597 | 0.017 |

| Completed college | 0.265 | 0.015 |

| Not reported | 0.010 | 0.003 |

| Mother’s marital status | ||

| Single | 0.137 | 0.013 |

| Married | 0.535 | 0.018 |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 0.221 | 0.014 |

| Not reported | 0.107 | 0.011 |

| PPVT score | 101.824 | 0.435 |

| Maltreatment index | 0.461 | 0.026 |

| Low GPA | 0.238 | 0.015 |

| Problems w/ teachers & peers | 0.271 | 0.016 |

| Problems completing homework | 0.327 | 0.017 |

| Frequent school absence | 0.280 | 0.016 |

Notes. N=1,778. All estimates are weighted using probability weights.

Table 2.

Emotional, behavioral, and school performance problems (%)

| Type of problem | Maltreatment index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ?²(3) | P | |

| Low GPA | 20.5 | 27.0 | 32.2 | 53.0 | 41.7 | 0.0001 |

| Problems w/ teachers & peers | 24.0 | 30.8 | 47.7 | 28.3 | 29.8 | 0.0026 |

| Problems completing HW | 29.8 | 36.9 | 34.4 | 50.5 | 17.2 | 0.0440 |

| Frequent school absence (8+ days) | 26.3 | 28.7 | 37.6 | 45.8 | 15.1 | 0.0604 |

| N | 1146 | 453 | 97 | 82 | ||

4.2 Regression estimates of school performance impairments

Table 3 shows linear probability model estimates of effects on the probability of having a low GPA. Youths with higher scores on the maltreatment index were significantly more likely to have a low GPA (δRE = +0.062, P=0.001). The Hausman test did not reject the random effects coefficient estimate for the maltreatment index (F1,1758=0.00, P=0.984). Also, youths whose racial/ethnic background was “other” were significantly less likely to have a low GPA (δRE = −0.107, P=0.010). Youths who scored higher on the PPVT were less likely to have a low GPA (δRE = −0.005, P<0.001).

Table 3.

Linear probability model estimates for having a low GPA

| Independent variable | Random effects | Fixed effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | t-stat | P | d | t-stat | P | |

| Maltreatment index | 0.062** | 3.20 | 0.001 | 0.059* | 2.34 | 0.020 |

| Male (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.022 | 0.76 | 0.449 | 0.048 | 0.39 | 0.695 |

| Age (Years) | 0.008 | 1.00 | 0.319 | 0.005 | 0.46 | 0.642 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.200 | 0.38 | 0.706 | |||

| Hispanic | −0.050 | −0.88 | 0.379 | |||

| Other | −0.107* | −2.56 | 0.010 | |||

| Adjusted family income ÷ 10,000 | −0.003 | −0.92 | 0.357 | |||

| Mother's educational attainment | ||||||

| Completed high school | −0.049 | −0.61 | 0.544 | |||

| Completed college | −0.147 | −1.58 | 0.115 | |||

| Mother's marital status | ||||||

| Married | 0.020 | 0.26 | 0.797 | |||

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | −0.001 | −0.01 | 0.989 | |||

| Low birthweight | −0.031 | −0.63 | 0.529 | 0.089 | 1.05 | 0.292 |

| Birth parents living with youth | ||||||

| Mother only | 0.076 | 1.80 | 0.071 | 0.173 | 1.67 | 0.095 |

| Father only | −0.054 | −0.69 | 0.490 | −0.256 | −1.12 | 0.261 |

| Neither mother or father | −0.061 | −0.77 | 0.444 | −0.058 | −0.34 | 0.731 |

| PPVT score | −0.005*** | −3.65 | 0.000 | −0.006** | −2.92 | 0.004 |

| Probability at sample means | 0.293 | |||||

| Hausman: F(1,1758) | 0.00 | 0.984 | ||||

Notes: Reference categories are white non-Hispanic race, mother did not complete high school, mother never married, and lives with both birth parents. Coefficients for indicators of missing mother's education and marital status are not shown. Estimates are probability weighted.

P<.05

P<.01

P<.001

Table 4 shows the estimated effects of the maltreatment index on the probability of having problems with teachers & peers and completing homework assignments, and of being absent from school 8 or more days.2 In the model for problems with teachers and peers, the maltreatment index coefficient did not reach statistical significance (δRE = +0.039, P=0.085). The fixed effects estimate of the maltreatment coefficient was imprecise (δFE = +0.013, P=0.698), and did not differ significantly from the random effects estimate (F1,1758=0.00, P=0.989). In the model for problems completing homework assignments, the random effects estimate indicated a positive effect of maltreatment (δRE = +0.054, P=0.007). The fixed effects estimate was less precise (δFE = +0.047, P=0.108) and similar in magnitude (F1,1758=0.00, P=0.972). In the model for 8 or more days absent from school, the random effects estimate did not reach statistical significance but had a positive sign (δRE = +0.034, P=0.092). The fixed effects estimate was essentially zero (δFE = −0.001, P=0.954).

Table 4.

Linear probability model estimates for other academic problems

| Independent variable | Random effects | Fixed effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d | t-stat | P | d | t-stat | P | |

| Problems w/ teachers and peers | 0.039 | 1.72 | 0.085 | 0.013 | 0.39 | 0.698 |

| Probability at sample means | 0.252 | |||||

| Hausman: F(1,1758) | 0.00 | 0.989 | ||||

| Problems completing homework | 0.054** | 2.69 | 0.007 | 0.047 | 1.61 | 0.108 |

| Probability at sample means | 0.324 | |||||

| Hausman: F(1,1758) | 0.00 | 0.972 | ||||

| Frequent school absence | 0.034 | 1.68 | 0.092 | −0.001 | −0.06 | 0.954 |

| Probability at sample means | 0.278 | |||||

| Hausman: F(1,1758) | 0.00 | 0.973 | ||||

Notes: Reference categories are white non-Hispanic race, mother did not complete high school, mother never married, and lives with both birth parents. Coefficients for socioeconomic and achievement indicators are not shown. Estimates are probability weighted.

* P<.05

P<.01

4.3 Structural model estimates

To help distinguish an interpretation of the reduced-form empirical relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent school performance, we also estimated "structural" equations for the relationship between maltreatment and three types of adolescent emotional and behavioral problems (attentional problems, symptoms of depression, and delinquency); and we estimated models of school performance that included as predictors these three measures of emotional and behavioral problems.3 Such a structural relationship (linking maltreatment with emotional/behavioral problems and problems with performance impairment) would imply that maltreatment can negatively impact school performance via its impacts on emotional/behavioral problems.

Random effects and fixed effects results showed that the maltreatment index was significantly, positively associated with attention problems (P=0.003), but not with depression (P=0.210) or delinquency (P=0.215). All three types of emotional/behavioral problems were significantly related to worse school performance on all measures. Attention problems were only marginally related to the probability of frequent school absence.

4.4 Sensitivity analyses

We repeated these analyses on subgroups defined by gender, sibling type (full or not full sibling relationship), and school age (<9th grade versus 9th grade and higher). None of these subgroups specifications produced substantively different findings.4

5. Discussion

Results from this study indicate that childhood maltreatment may adversely impact adolescents' performance in school. We found that more intensive forms of childhood maltreatment (before the start of 6th grade) were robustly associated with low GPA and problems completing homework assignments. Non-significant associations were identified for problems with teachers and peers and frequent absence from school. These associations were robust to controls for socioeconomic characteristics and academic achievement, as well as to family specific effects, and appeared to be moderated by attentional problems in adolescence. As far as we are aware, ours is the first study to show evidence of adverse effects of maltreatment on academic performance in a representative community sample of U.S. adolescents.

It is surprising that the effects of childhood maltreatment, and parents’ influence in general, on children’s later academic performance has received virtually no attention in education policy forums. As a result of the No Child Left Behind legislation (U.S. Department of Education, 2005), schools with a disproportionate number of poorly performing students are subject to a reduction of their Department of Education funding if their students do not show sufficient improvement on performance measures (i.e., achievement test score gains). At the same time, greater attention has been given to the investment return on public expenditures on services designed to improve the quality of children’s early family experiences (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Middle and high school students who do not adhere to schools' rules of conduct, who perform poorly academically, and who have interpersonal difficulties have worse long-term employment outcomes and lower earnings in adulthood (Cawley, Heckman, & Vytlacil, 2001; Heckman & Rubinstein, 2001). Thus, the results of this and other studies of maltreatment have potentially far-reaching implications for education policy.

It is difficult to compare our findings with those of other studies. This is the first study to apply the family fixed effects methodology to this topic, and most previous studies were of convenience samples and younger children. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with several previous studies that show a negative association between maltreatment and school performance (Erickson et al., 1989; Eckenrode et al., 1993; Kurtz et al., 1993; Kendall-Tackett & Eckenrode, 1996; Rowe & Eckenrode, 1999; Shonk & Cicchetti, 2001). A study by Zolotor, Kotch, Dufort, Winsor, Catellier, & Bou-Saada (1999), in particular, found a similar pattern of multivariate results using data derived from substantiated reports to child protective services agencies.

Contrary to the modest levels of some of the associations identified in this study, clinical samples of maltreated children often show profound deficits in interpersonal functioning (Shonk & Cicchetti, 2001). This contrast may be due to this study's use of a national household sample, which could substantially underrepresent the clinical population, or to the imprecision of measures of maltreatment in the AddHealth. Our measures of maltreatment were limited in content and were based entirely on retrospective self-report, which may contain substantial measurement error (Prescott, Bank, Reid, Knutson, Burraston, & Eddy, 2000). Prescott et al. (2000) also provide evidence that retrospective reports of these types of childhood events have high specificity (few false positives) but only moderate sensitivity (a substantial number of false negatives). In principle, the moderate sensitivity of self-reports will tend to reduce the magnitude of estimated effects.

The low magnitude of some of the associations may also point to children's resiliency and to heterogeneity of effects of parenting on maltreated children (Kurtz et al., 1993; Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997; Shonk & Cicchetti, 2001). Neurobiological vulnerabilities or environmental factors may influence maltreated children’s long term outcomes (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman 2002), but these effects are poorly understood and were not measured in this study.

Another interpretation of our results is suggested by our finding that adjustment for family-specific intercepts removed much of the statistical association between maltreatment and academic performance. This is consistent with the possibility that episodes of maltreatment are symptomatic of multiple aversive aspects of the shared family milieu. Under this perspective, dynamics associated with negative family interactions (Patterson et al., 1989) could lead to maltreatment of all children and also could increase the likelihood that they have difficulty in school. Because maltreatment and the broader family environment may be intertwined, efforts by researchers to disentangle family dynamics in order to express the unique effects of maltreatment could be unconstructive.

An alternative explanation of the low precision of the fixed effects estimates is lack of variability in measures across siblings. Within-family variation accounted for approximately one-fifth to one-third of the overall standard deviation in maltreatment experiences, depending on the measure of maltreatment. This suggests that although intra-family variability was significant, most of the sampled variation was discarded in the fixed effects specification.

5.1 Implications for education policy

Our findings suggest that educators (elementary through high school) should be more aware that past or continuing maltreatment could be negatively affecting a student’s performance in school. Greater awareness of maltreatment could lead teachers to respond more effectively to students who appear to have poor motivation, perform inconsistently on assignments, or are behaviorally difficult. In addition, schools should be better prepared to help maltreated children through formalized intervention and support. Examples of successful treatment programs for maltreated youth exist for sexual abuse (Cohen, Mannarino, & Knudsen, 2005) and for school-based treatment of childhood trauma (Stein, Jaycox, Kataoka, Wong, Tu, Elliott, et al., 2003), but efforts to generally implement these or similar interventions in schools or in cooperation with schools have been uncommon (Cicchetti, Toth, & Hennessy, 1993).

A central dilemma with implementation is determining which school-system responses and service interventions are most effective and affordable. Our results suggest that broadly targeted school-based prevention strategies may rarely be more effective than doing nothing, and could be much more costly, because maltreatment is not a highly specific predictor of school performance impairments. One alternative is to create specialized service interventions for maltreated children or for any child who experiences negative effects from past or ongoing traumas. The main challenges to intervention are the difficulty of getting children and adolescents to use intervention services and the difficulty of obtaining financing for services. One possible approach would be to increase direct collaboration between schools and social service agencies. This type of collaboration is currently not the norm, partly owing to administrative divisions between social service agencies and education systems as well as to their reliance on separate sources of financing. How to set up financing systems that encourage interagency collaboration is an interesting topic for future analysis.

5.2 Limitations

Two other limitations of our data and analyses are important to the interpretation of our findings. One key issue is that almost any practical measure of the quality of a child’s past experiences is vulnerable to misrepresentation and recall biases (Prescott et al., 2000). Respondents have incentives to positively or negatively shade their reports of past experiences. Stigma or embarrassment may lead to substantial underreporting of negative events, whereas ex-post rationalization of low achievement may lead to exaggeration. Misreporting could have resulted in estimated effects of maltreatment that are biased toward zero. It is significant here that childhood maltreatment and school performance measures in the Add Health were collected approximately five years apart. A respondent’s present mood (at Wave III) could have influenced their reports of past maltreatment, but it is unlikely that their present mood could have contaminated measures of their school performance, taken five years earlier.5

Finally, it is notable that differences in the personal characteristics of the individuals in each sibling pair (e.g., personality, temperament, cognitive capabilities) may have influenced their exposure to maltreatment and their performance in school. If this is the case, the fixed effects procedure would not eliminate bias due to omitted variables. This interpretation cannot be ruled out. However, it is reasonable to presume that certain types of maltreatment, particularly sexual abuse and neglect, are not attributable to children’s characteristics or behavior, and are therefore less likely to be associated with outcomes due to reverse causation.

5.3 Conclusion

This study establishes that maltreatment is connected with below average school performance during adolescence, even after controlling for observed and unobserved family and neighborhood effects. The effects of maltreatment should be taken into account in developing schools’ and educators’ responses to poor performance among their students and in guiding the development of service interventions. Maltreatment may negatively affect scholastic performance indirectly through effects on cognitive deficits. Our results provided less support for effects operating through learned interactional styles.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was received from NIMH under grants K01-01647 and K24-MH01790, and from the Center for Adolescent Health Promotion and Disease Prevention under a Development Award to Dr. Slade. The authors thank James Rice for able research assistance. They also thank Fred Zimmerman, Thomas McGuire, and John Mullahy for advice and comments on preliminary drafts. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design.

Footnotes

Following Wooldridge (2002; pp. 454–457), the linear probability model is used here for convenience. It is appropriate for use in this context, because of the limited range of values taken by the key predictor variables. In sensitivity analyses, we also estimated similarly specified models using logistic regression and the fixed effects logit specification. Those models resulted in quantitatively similar, but less precise, estimates of maltreatment's effects. The two specifications could not be directly compared using Hausman tests, which require linearity. In addition, the fixed effects logit excluded many non-informative cases, again making comparison to random effects estimates difficult. Therefore, we do not present the results of those analyses.

Coefficients for sociodemographic variables and PPVT are not shown due to space limitations. Complete results are available from the authors by request.

The results of these analyses are not shown here, due to space limitations, but are available from the authors, by request.

Results not shown due to space limitations.

An additional concern is that siblings less negatively affected by past maltreatment could be less likely to report past maltreatment. If so, fixed effects estimates would be biased toward detection of an effect of maltreatment. To that point, we note differential reporting by paired siblings would result in false detection of a school performance effect only if there is a negative correlation between school performance at a certain point in time and the likelihood of falsely reporting maltreatment at least five years later. Although this hypothesis cannot be ruled out by available evidence, we are not aware that it has ever been tested.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Advances in applied developmental psychology: Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Vol. 8. 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Cassidy J. Attachment: Theory and evidence. In: Rutter ML, Hay DF, Baron-Cohen S, editors. Development through life: A handbook for clinicians. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 1994. pp. 373–402. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, Kashani JH. Phenomenology of major depression from childhood through adulthood: analysis of three studies. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;145(10):1222–1225. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.10.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley J, Heckman J, Vytlacil E. Three observations on wages and measured cognitive ability. Labour Economics. 2001;8:419–442. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The role of self-organization in the promotion of resilience in maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:797–815. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Hennessy K. Child maltreatment and school adaptation: Problems and promises. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Child Abuse: Child Development, and Social Policy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1993. pp. 301–330. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Knudsen K. Treating sexually abused children: 1 year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(2):135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A, Keeler G. Adolescent outcomes of childhood disorders: The consequences of severity and impairment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(2):121–128. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman PH. The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development. 1987;58(5):1244–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenrode J, Laird M, Doris J. School performance and disciplinary problems among abused and neglected children. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson M, Egeland B, Pianta R. The effects of maltreatment on the development of young children. In: Cicchetti D, Carlson V, editors. Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse & neglect. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 647–684. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. Child sexual abuse. New York: The Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Flisher AJ, Kramer RA, Hoven CW, Greenwald S, Alegria M, Bird HR, Canino GM, Connell R, Moore RE. Psychosocial characteristics of physically abused children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(1):123–131. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorey KM, Leslie DR. The prevalence of sexual abuse: Integrative review adjustment for potential response and measurement biases. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Florey F, Tabor J, Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research design. 2003 [WWW document]. URL: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Heckman JJ, Rubinstein Y. The importance of noncognitive skills: Lessons from the GED testing program. American Economic Review. 2001;91(2):145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl EC, Herrenkohl RC. A comparison of abused children and their non-abused siblings. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1979;18:260–269. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra MB, Van Der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Child and adolescent problems predict DSM-IV disorders in adulthood: A 14-year follow-up of a Dutch epidemiological sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(2):182–189. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall-Tackett KA, Eckenrode J. The effects of neglect on academic achievement and disciplinary problems: A developmental perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20(3):161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz PD, Gaudin JM, Wodarski JS, Howing PT. Maltreatment and the school-aged child: School performance consequences. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1993;17(5):581–589. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(93)90080-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer RE, Giordani B, Boivin MJ, Halle N, Glasgow B, Alessi NE, Berent S. Effects of depression on memory performance and metamemory in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33(5):679–685. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199406000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz A. Home investments in children. Journal of Political Economy. 1974;82(2 Part II):S111–S131. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. Risk factors in the child: a study of abused children and their siblings. In: Martin HP, editor. The abused child: A multidisciplinary approach to developmental issues and treatment. Cambridge: Ballinger Publishing; 1976. pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Cicchetti D, Barnett D. The impact of subtype, frequency, chronicity, and severity of child maltreatment on social competence and behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:121–143. [Google Scholar]

- McGonigle MM, Smith TW, Benjamin LS, Turner CW. Hostility and nonshared family environment: A study of monozygotic twins. Journal of Research in Personality. 1993;27:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44(2):329–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott A, Bank L, Reid JB, Knutson JF, Burraston BO, Eddy JM. The veridicality of punitive childhood experiences reported by adolescents and young adults. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24(3):411–423. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey SL, Ramey CT. Early childhood experiences and developmental competence. In: Danziger S, Waldfogel J, editors. Securing the future: Investing in children from birth to college. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2000. pp. 122–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rapport MD, Denney CB, Chung KM, Hustace K. Internalizing behavior problems and scholastic achievement in children: Cognitive and behavioral pathways as mediators of outcome. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;30(4):536–551. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(2):330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe E, Eckenrode J. The timing of academic difficulties among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23(8):813–832. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields AM, Cicchetti D, Ryan RM. The development of emotional and behavioral self-regulation and social competence among maltreated school-age children. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:57–75. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400005885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonk SM, Cicchetti D. Maltreatment, competency deficits, and risk for academic and behavioral maladjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37(1):3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, Wong M, Tu W, Elliott MN, Fink A. A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(5):603–611. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd PE, Wolpin KI. On the specification and estimation of the production function for cognitive achievement. Economic Journal. 2003;113(485):F3–F33. [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D. The impact of relatedness with mother on school functioning in maltreated children. Journal of School Psychology. 1996;34(3):247–266. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. No child left behind: Expanding the promise, guide to President Bush’s FY2006 education agenda. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Youth violence: A report of the Surgeon General. Washington D.C.: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zolotor A, Kotch J, Dufort V, Winsor J, Catellier D, Bou-Saada I. School performance in a longitudinal cohort of children at risk of maltreatment. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 1999;3(1):19–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1021858012332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]