Abstract

TGFβ3 signaling initiates and completes sequential phases of cellular differentiation that is required for complete disintegration of the palatal medial edge seam, that progresses between 14 to 17 embryonic days in the murine system, which is necessary in establishing confluence of the palatal stroma. Understanding the cellular mechanism of palatal MES disintegration in response to TGFβ3 signaling will result in new approaches to defining the causes of cleft palate and other facial clefts that may result from failure of seam disintegration. We have isolated MES primary cells to study the details of MES disintegration mechanism by TGFβ3 during palate development using several biochemical and genetic approaches. Our results demonstrate a novel mechanism of MES disintegration where MES, independently yet sequentially, undergoes cell cycle arrest, cell migration and apoptosis to generate immaculate palatal confluency during palatogenesis in response to robust TGFβ3 signaling. The results contribute to a missing fundamental element to our base knowledge of the diverse roles of TGFβ3 in functional and morphological changes that MES undergo during palatal seam disintegration. We believe that our findings will lead to more effective treatment of facial clefting.

Keywords: Palate, TGFβ, Migration, Apoptosis, MES

Introduction

Cleft palate, the most common craniofacial deformity, is caused by the failure of palatal midline epithelial seam (MES) cells to disintegrate, which is necessary for palatal mesenchymal confluence. While Transforming Growth Factor (TGF) β3 plays an important role in a number of model systems, it has been well established that it plays an essential role in palatogenesis (Murray and Schutte, 2004), particularly at a later stage of palatogenesis when the newly formed MES must undergo disintegration for palatal confluency. We and others have demonstrated that TGFβ3 regulates disintegration of the palatal MES after adhesion of the palatal shelves, and that become part of the palate connective tissue, thus establishing confluence of the palatal stroma in murine model system (Kaartinen et al., 1997). Mice null for TGFβ3 are normal in most regards, but are born with cleft palate (Kaartinen et al., 1995). The cellular mechanism underlying seam degeneration and the fate of the MES cells have been a major focus of the field for more than a decade. However, controversies still remain on this issue. Using several labeling techniques, two major models have been proposed for seam degeneration: migration (Hay, 1995; Jin and Ding, 2006; Kaartinen et al., 1997; Kang and Svoboda, 2005; Lagamba et al., 2005; Nawshad and Hay, 2003; Pungchanchaikul et al., 2005; Shuler et al., 1992; Sun et al., 2000b; Takahara et al., 2004; Takahara S, 2004; Takigawa and Shiota, 2004) or apoptosis (Cuervo and Covarrubias, 2004; Dudas et al., 2006a; Dudas et al., 2006b; Taniguchi et al., 1995; Vaziri Sani et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2006), while proponents of either hypothesis do not agree with the alternate hypothesis. However, all are in agreement that both events are caused by TGFβ3.

The biggest weakness in our understanding of palate development is the connection between TGFβ3 signaling and palatal MES cell behavior. While there are several approaches to this problem, we were able to learn much from simply assembling a more complete picture of the localization and timing of signaling within the cells during palatal MES disintegration. By using MES cells in culture, we were able to develop reliable stages of palatogenesis in MES cell culture that mimic the in vivo system to interpret TGFβ3 signal in a greater depth which otherwise was not possible in in vivo studies.

While, our previous (Nawshad and Hay, 2003; Nawshad et al., 2004; Nawshad et al., 2007) results demonstrated that TGFβ3 signaling is capable of causing cell migration in the MES epithelia. However, in this study we show that immediate response of MES to TGFβ3 induction is to undergo cell cycle arrest prior to cell migration. At later stages of palatogenesis, TGFβ3 exerts its effects in MES cell apoptosis to complete palatal confluency; however, apoptosis is independent of migration. These exciting data suggest that TGFβ3 provide a novel mechanism for three different yet chronological phenotypical changes (cell cycle arrest, cell migration and apoptosis) which are essential for palatal MES disintegration, and is the first evidence of multiple roles of TGFβ3 in palatogenesis.

Material and Methods

Culture of isolated primary MES cells

Fifteen (15) timed-pregnant CF1 mice (Charles Rivers Laboratories, Inc., Boston, MA) were used for these studies. From our earlier work (Lagamba et al., 2005; Nawshad and Hay, 2003; Nawshad et al., 2004) we have found that the CF1 mouse strain weighs (50gm) more than other normal strains and so do their embryos. The size of the developing palatal shelves is substantially larger which allows more cells to be collected for protein/RNA and DNA analysis. We obtained about 8-10 healthy 14 days post coitum (dpc) embryos from each pregnant mouse. For normal palates, protocols and methods of anesthesia, surgery, collecting embryos, and dissecting palatal shelves from pregnant mice have been undertaken by us previously and described in detail in Lagamba et al., (2005); Nawshad and Hay, (2003); Nawshad et al., (2004). Isolated palates were cultured at 37°C in a humidified gas mixture incubator (5% CO2 and 95% air), and the medium was changed every 24 hours. Palatal shelves were processed with two different treatment regimens: (i) For placing the MES cells in culture, palatal shelves were processed and treated as described below and mentioned in further detail in Nawshad et al., (2007). (ii) For organ culture, palatal shelves were collected as described in Lagamba et al., (2005); Nawshad and Hay, (2003); Nawshad et al., (2004).

The single cell thick periderm covering on each shelf was removed by incubating the shelves with Proteinase K for 1h in 37°C. The shelves were then cultured at 37°C for 12 hours to allow brief adherence to the corresponding opposite shelf (adhered). Adhered shelves in organ culture was then cut close to the seam to ensure limited or no mesenchymal tissues attached to isolated seam. The shelves were then separated and treated with Dispase II for 30 min. to allow the primary MES cells to separate from the underlying basement membrane so that we could collect epithelial cells without any mesenchymal contamination. Cells were then cultured in flasks and harvested at the exponential growth stage (∼80% confluence) before any exogenous treatment began. From one pair of palates, we could isolate enough cells to seed one T-25 flask. The cells were splitted 1:2 every three days as many as 5 times to generate ample MES cells with preservation of healthy growth and morphology for experiments and storage. Approximately 106 MES cells were used for each treatment conditions. In vivo, MES cells produce optimum endogenous TGFβ3, however, when MES cells were removed from primary tissue, TGFβ3 ceased its usual high expression in vivo to only a mild expression (Nawshad et al., 2007) as well as (Fig. S1). Such lowexpression was not sufficient to induce cellular changes. Since TGFβ3 expression increases during MES disintegration in vivo (Lagamba et al., 2005) as well as shown in the supplementary results (Fig. S1), we added exogenous TGFβ3 at 5ng/mL every 24 hours to the MES cells to mimic the in vivo results.

Clonal analysis for homogeneity of the MEE cells

Primary MES cells obtained from paired palatal shelves were trypsinized and single cell, 10 cells and 100 cells of clonal density were isolated under the microscope, seeded in triplicate plated onto a regular feeder-layer in separate gelatin-coated 60-mm Petri dishes containing Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium, DMEM (ATCC, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, CA), 100U/ml penicillin and 100μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO). Whenever needed FBS was removed from appropriate experimental conditions. All cultures were incubated for 3 days in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37°C in (5% CO2 and 95% air) and medium was changed every 24 hours. Colonies were monitored microscopically on a daily basis to ensure that they were derived from single cells. Colonies were counted and the cloning efficiency (CE) determined from the formula CE (%) 5 (number of colonies/number of cells seeded) 100x. A representative number of cells contained within the grid were counted from the center of the colony and also for the edges of the colony, where cells were loosely packed, and then the number of grids/colony counted and multiplied by cell number/grid to give a total cell count per colony. Clusters of cells were considered colonies when they were visible macroscopically and contained greater than 100x cells from the original number of seeded cells.

After 3 days of cultivation, plates were carefully scored for the presence of a uniform homogenous colony of epithelial cells under a microscope. Productive colonies were photographed under a Zeiss Axiovert microscope. We have observed (by FACArray) that a small percentage (1.2%) of MES cell in culture dies before reaching 70% confluence. Only those colonies from which productive clone of 100% live epithelial cells were derived was then transferred by trypsinization to two indicator dishes. One dish was used for serial propagation and further analysis. The second dish was fixed with Buin's fixative for 10 min after a PBS wash for the assessment of cobblestone epithelial morphology and stained with E-cadherin, Desmoplakin, and Desmoglein for classification of epithelial clone type.

Treatment conditions

Only necessary induction or inhibition was carried out with appropriate doses and untreated MES cells were used as the control. The concentration of each inhibitor or activator has already been optimized to minimize the toxicity for MES cells in previous studies (Lagamba et al., 2005; Nawshad and Hay, 2003; Nawshad et al., 2004). Additional treatment conditions are included later in appropriate sections. zVAD-fmk (20μM) obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (MO); GFP-retrovirus encoding full length E-cadherin cDNA (kindly provided by Prof. Keith R. Johnson, UNMC, NE) and empty GFP-retrovirus vector (kindly provided by Dr. Jim Wahl, UNMC, NE).

Immunofluoroscene and Immunoblot

As described earlier in Nawshad et al., (2007). Antibodies were obtained from the following sources: E-cadherin (kindly provided by Dr. James Wahl, UNMC, NE); Vimentin (Zymed, CA); α-SMA (Sigma-Aldrich, MO), BCL-2, Bax, c-Myc, β-Actin, Fibronectin (Abcam, MA); Apoptotic Inducing Factor (AIF), p15, p21, p27, Caspase 3, Caspase 9, cleaved Caspase 3 and PCNA (Cell Signaling Technology, MA), anti-single stranded (ss) DNA (Bender MedSystems, CA), TGFβ3 (R&D Systems, CA). Affinity purified Cy3, Cy5, Fluoroscene and Rhodamine conjugated secondary Antibody (Invitrogen, CA).

Scratch wound assay

As shown earlier in Nawshad et al., (2007). Briefly, MES cells were grown to 100% confluence in six-well culture plates that underwent straight line-shaped scratch by scraping with a sterile pipette tip to uniformly wound the cells. Both treated and untreated wounded cultures were examined for 72 hours. The migration of cells (or gap filling) was observed every 12 hours through phase-contrast microscopy where cells were morphologically assessed for the migratory phenotype. The center of the scratch line was used for positioning.

Transwell cell migration assay

As demonstrated earlier in Nawshad et al., (2007) using the Innocyte™ Cell Migration Assay (EMD Biosciences, CA). Briefly, 8μm pore size transwell migration chambers in 96-well plates were used for migration analyses. Both treated and untreated MES cells were allowed to migrate across the membrane insert toward media in the presence of serum (10%) for 24 to 48 hours at 37°C (chemotactic migration). Cells that migrate through the membrane and attach to the lower side of the cell culture insert were subsequently detached using cell detachment buffer containing Calcein-AM fluorescent dye (excitation max.: 485nm; emission max.: 520nm). The data was obtained using BD Bioanalyzer™ fluorescent plate reader (BD Biosciences, CA)

Cell Cycle Analysis

MES cells were grown in 10% FBS containing DMEM in T-25 flasks. Approximately 60% confluent cells were treated with 6.0μM Aphidicholin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) for 16 hours, washed with Hanks Buffered Saline Solution (HBSS) (Mediatech, VA) and released into complete medium for 30 min. Cells were then treated with complete medium containing TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) for 72 hours changing every 24 hours. Cells were collected every 12 hours for cell cycle analysis by BD FACSArray Bioanalyzer (BD Biosciences, CA). Cells were detached by trypsin and collected in 15 mL tube after washing with 1x PBS. Then cells were fixed by adding ice-cold 70% ethanol drop by drop while slowly vortexing and incubated for 24 hours at −20°C. Fixed cells were then washed once with 1x PBS and adjusted the cell concentration to 4 × 105 and stained with 1mg/mL of Propidium Iodide (PI) and RNase (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) for 30 min at room temperature. These PI stained cells were then analyzed by BD FACSArray Bioanalyzer using green laser at 532nm wavelength.

Live and Dead Cell Staining

MES cells were grown in 10% FBS containing DMEM in T-25 flasks. Approximately 60% confluent cells were treated with 6.0μM Aphidicholin for 16 hours, washed with HBSS and released into complete medium for 30 min. Cells were then treated with complete medium containing 5ng/mL of TGFβ3 for 72 hours. Cells were collected every 24 hours for live and dead cell stain analysis by BD FACSArray Bioanalyzer. Vibrant cell metabolic assay kit and Sytox red dead cell stain were purchased from Invitrogen. Cells were stained according to manufacturer's protocol. In brief, first, the floating cells were collected by spin down. 4mL of 1x PBS was added to the flask and 1mL of 1x PBS was added to dissolve the collected floating cells and then added this dissolved pellet to the flasks. Then 2μM concentration of C12-resazurin was added to those flasks and incubated for 15 min in 37 °C. After this, cells were detached by trypsin and collected, dissolved the pellet in 5nM Sytox Red stain/mL of 1x PBS and incubated for a minimum 15 mins. at room temperature in dark. These stained cells were analyzed by BD FACSArray Bioanalyzer using green laser at 532nm wavelength and red leaser at 635nm wavelength for C12-resazurin and Sytox Red stain, respectively.

Apoptosis assays

(a) Detection of LMW DNA fragments: Nuclear DNA underwent conventional 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis to show any oligo DNA fragments. Briefly, 1ml of lysis buffer from DNA extraction mixed with 1ml of ethanol were kept at −20°C for 18h and then centrifuged. The pellet was rinsed with 70% ethanol, centrifuged again, and the final DNA pellet was diluted in 20μl of 10mM Tris, pH 8, 1mM EDTA, and 10μg/ml RNase. Conventional 1.5% agarose-gel electrophoresis was performed. Gels were stained with SYBR Safe (Molecular Probes); (b) DNA fragmentation and integrity Assay by Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: MES cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 until 60-70% confluence was reached. We used CHEF Mammalian Genomic DNA plug Kit (BioRad, CA), that included all reagents and buffers, to undertake this experiment. A λ DNA–Hind III PFGE marker were purchased from and New England Biolab (MA). DNA plugs were prepared according to manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, an aliquot of 0.2×106 cells/mL were treated with 5ng/mL of TGFβ3 for 72 hours and were collected every 12 hours. Cells were washed by centrifugation (1000x g, 5 min, 4°C) and mixed with 2% CleanCut agarose (Bio-Rad, CA) to a final concentration of 0.75% at 50°C. The cells/agarose mixture was transferred to plug molds and solidified on ice. Agarose plugs were lysed with Proteinase K in reaction buffer and were incubated overnight at 50°C. Thereafter, plugs were washed four times in a 1× wash buffer and stored at 4°C in this buffer. Washed plugs were inserted into the wells of a 1% agarose gel prepared in 0.5x TBE buffer. The gel was run using CHEF DRIII (Bio-Rad) apparatus set to the following protocol: run time, 14h; switch time from 5 to 50s; voltage gradient, 6 V/cm. After electrophoresis the gel was stained with 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide and examined under UV light. (c) TUNEL assay: To clarify the spatial distribution of DNA fragmentation, we performed TUNEL which employs TdT to add dUTP to the fragmented DNA ends. We used TUNEL Apoptosis Detection kit (Millipore, MA). (d) Detection of AIF protein expression: As described by (Frankfurt and Krishan, 2001), briefly MES cells were fixed in methanol - PBS (6:1) for 48 hours. Fixed cells were re-suspended in 0.25 ml of formamide (5×105 cells in 15-ml plastic tubes) and cells were washed with 2 ml of 1% non-fat dry milk in PBS, re-suspended in 100ml of ssDNA monoclonal antibody (10mg/ml in PBS containing 5% FBS) and incubated for 15 min. Cells were then rinsed with PBS and stained with fluorescein-conjugated anti-mouse IgM (1:50 in PBS containing 1% non-fat dry milk) for 15 min and cytocentrifuge preparations of antibody-stained cells were counterstained with 0.1mg/ml DAPI in PBS for 10 min.

Results

Using primary cultures derived from palatal MES cells isolated from 14dpc mouse embryos, we showed that TGFβ3 signaling chronologically orchestrates highly synchronized phenotypical changes to bring about successful palatal confluency during palatogenesis. TGFβ3 induces cell cycle arrest, represses cell-cell adhesion to activate MES cell disintegration by migration, and then induces apoptosis of MES cells during palate development. We identified key regulatory molecules in the TGFβ3 signaling pathways that induce cell cycle arrest, migration and apoptosis in a time dependent fashion. We, however, do not know the mechanisms of activation of exact pathways that TGFβ3 employs to elicit these three morphological changes needed for successful MES cell disintegration. Our results are described in the following subheadings describing each figure chronologically:

Stages of palatal MES disintegration and the role of apoptosis in MES disintegration (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1. Stages of normal palate development.

Single palatal shelves collected from 14dpc CF1 mouse embryos were placed together with the corresponding opposite palatal shelf and incubated in organ culture in the presence of exogenous recombinant TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) for up to 72 hours (added every 24 hours). They were collected at 12, 24, 36, 48, 60 and 72 hours of culture and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Palatal shelves adhered to form the MES by 12 hours (A, white arrow). At 24 hours, the seam began to separate into small islands of epithelial cells (B). By 48 hours, a few MES cells remained (C). By 72 hours, the seam completely disintegrated and palatal confluency was complete (D, blue arrow). However, when the single palatal shelves were treated with TGFβ3-blocking antibody (5ng/ml), seam remained intact as late as 72 hours (E, white arrow), and when apoptosis were blocked with pan Caspase inhibitor, zVAD-fmk (20μM), remnant of the MES cells were still present at the oro-palatine and naso-palatine triangle and fusion was incomplete (F, white arrow). Single palates were treated with the inhibitors for 24 hours to have their effect before the shelves were placed together to form a seam. Each bar value, as stated, represents the size and magnification of the image.

First we established that whole palates from 14 dpc embryonic mice undergo MES disintegration in response to exogenous TGFβ3 when removed and placed in organ culture. The results showed that the newly formed intact seam at 12 hour (A, white arrow) gradually disintegrate in 24 and 48 hours (B, C) and eventually disintegrate completely to form confluent palates by 72 hours (D, blue arrow). These stages (A-D) were similar to those seen in vivo. Palates treated with anti-TGFβ3 blocking antibody, formed a seam, but the MES did not undergo disintegration (E; white arrows). To demonstrate the necessity of apoptosis in MES disintegration, we blocked apoptosis by treating the palatal shelves with pan Caspase inhibitor, zVAD-fmk, which had a late effect, and caused incomplete MES disintegration (F, inset, white arrow). These results demonstrate the importance of TGFβ3 in palatal confluency and suggest that apoptosis does take place late for the completion of MES disintegration.

Epithelial cells derived from single clone of MES cells (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. Collection of primary MES cell.

Palate medial edge epithelial cells from CF-1 mouse (Charles River Laboratories) embryos were separated from underlying mesenchyme using Dispase II (Roche), from palatal shelves adhered for 12 hours in organ culture, as previously described in Nawshad et al., (2007) (A). Cells were then cultured into primary cell lines in DMEM + 10% FBS + 1% penicillin/streptomycin (B). Following confirmation of the clonal homogeneity of the MES epithelial cells (see material and methods for detail) and that they derive from single clone devoid of any mesenchymal contamination, MES cells were stained for the expression of epithelial markers such as E-cadherin (C, arrow), Desmoplakin (D, arrow) and Desmoglein (E, arrow) to demonstrate that isolated cells maintained fully and only epithelial characteristics. Cells were treated with exogenous recombinant TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) every 24 hours and all experiments were performed in triplicate. Each bar value, as stated, represents the size and magnification of the image.

Before, we undertook any experiment; we first confirmed that MES collected from 14 dpc CF1 embryos are pure clone of epithelial cells and devoid of any mesenchymal contamination. Using Dispase II, we were able to dissect only the MES cells from the surrounding mesenchyme. Once separated from the intact mesenchyme, only the epithelial cells slough-off (A) with no affect on the mesenchyme. We, then, collected 1, 10 and 100 cells (B) and by employing clonal homogeneity experiments (see material and methods), we were able to culture pure homogenous population of MES only. We confirmed that these clone of MES cells have all epithelial characteristics by demonstrating increased expression of E-cadherin (C), Desmoplakin (D) and Desmoglein (E).

TGFβ3 sequentially activates cell migration and then apoptosis (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3. TGFβ3 induces MES migration followed by apoptosis.

80% confluent MES cells were treated with TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) every 24 hours for 72 hours. MES cells showed gradual phenotypical changes from adhered epithelial (A) to fully motile and migratory fibroblastoid at 48 hours (B) but began to die at 60 hours (black arrow) as apoptotic bodies began to appear (C) and apoptosis continued to increase at 72 hours (D). When apoptosis was blocked with zVAD-fmk, MES cells continued to migrate (E-H). In the presence of TGFβ3, MES cells underwent migratory changes (J), and the cells remained migratory even after TGFβ3 signaling was blocked with blocking TGFβ3 antibody (K, L). Bar value (50μm) represents the size and magnification of the image.

To study the chronological events of phenotypical changes that MES undergo in response to TGFβ3 in cell culture condition, we treated the 80% confluent MES cell with recombinant exogenous TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) and monitored its changes under phase contrast microscope. We found that after 48 hours of TGFβ3 treatment, MES cells in culture became motile (B), but at 60 hours, cells began to die and apoptotic bodies were seen (C, arrow). At 72 hours, the numbers of apoptotic cells continued to increase (D, arrow). When apoptosis was blocked by zVAD-fmk, MES cells maintained a migratory phenotype like that seen in Fig. B, showing that apoptosis was not involved in cell migration (E-H). When TGFβ3 signaling was blocked after MES cells have converted to a migratory phenotype (J), MES cells did not revert back to epithelia (K) nor did they progress to apoptosis (L) indicating that TGFβ3-induced migratory MES cells require continuous TGFβ3 to undergo apoptosis These results suggest that migration and apoptosis in the MES cells are results of TGFβ3 signaling and that they are sequential but independent events.

TGFβ3 down regulates E-cadherin in cultured MES cells (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4. E-cadherin is reduced in response to TGFβ3.

MES cells were grown to 80% confluence as described in Fig. 3. Untreated MES showed membrane localization of E-cadherin (A). E-cadherin was significantly reduced when the cells were treated with TGFβ3 for 24 hours (B). MES cells were stained with fluorescence (A, B) conjugated antibody against E-cadherin and counter stained with DAPI. At 48 hours, when MES cells become migratory as a results of reduced cell-cell adhesion E-cadherin, migratory MES cells expressed Fibronectin (C, Alexa Fluor 488), Vimentin (D, Alexa Fluor 594) and α-SMA (F, Alexa Fluor 350) (merged all proteins in E). Each bar value, as stated, represents the size and magnification of the image.

We investigated the expression of E-cadherin as MES cells progress through different phases of cellular changes in response to TGFβ3. We demonstrated that cultured MES cells expressed high levels of E-cadherin, remained epitheloid and maintained strong cell-cell adhesion (A). When treated with exogenous TGFβ3 (5ng/mL), MES cells showed a significant reduction in E-cadherin protein expression within 24 hours (B). In addition, at 48h, motile MES cells expressed proteins such as Fibronectin (C), Vimentin (D) and α- Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA) (F), which are typical of migratory cells. These results demonstrate that repression of E-cadherin protein expression is an early event and once cell-cell adhesion is lost, MES cells become motile and express migratory proteins.

Repression of E-cadherin is necessary for cell migration: (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5. MES cells with increased E-cadherin do not migrate.

Confluent MES cells were transiently infected with GFP-retrovirus encoding full length E-cadherin cDNA as well as control GFP without the E-cadherin cDNA (A, B). Infection rate was high (C, D) for both the constructs. Transduced MES cells expressed GFP within 48 hours. We used Scratch wound assays (G, H and I-K) to morphologically assess the migratory phenotype and evaluate the cell motility. MES cells were treated with TGFβ3 (5ng/mL). After 48 hours, only the GFP-control cells were motile and migrated into the gap (F, H - phase contrast). But MES cells expressing high E-cadherin failed to migrate and remained epithelial (E, G - phase contrast). TGFβ3 promotes cell migration and motility independent of apoptosis: Our results also showed lack of cell migration in untreated (control) MES cells (I). MES cells treated with TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) become motile (J). Blocking apoptosis with zVAD-fmk, had no significant role in MES cell migration and motility (L, K). (mean ± SD; n=3; p<0.05; RFU- Relative Fluorescence Unit). Transwell cell migration assay results were compared with Scratch wound assay and were found to be in accord as cell migration was also induced upon TGFβ3 and transiently infected with GFP-retrovirus encoding full length E-cadherin cDNA can inhibit cell migration, whereas inhibiting apoptosis with zVAD-fmk has limited or no effect on migration (L). Each bar value, as stated, represents the size and magnification of the image.

To examine the importance of E-cadherin repression for cell migration, we retrovirally infected the confluent MES cells with a full length E-cadherin cDNA-GFP to maintain increased E-cadherin expression (A, C) or a control GFP viral construct without E-cadherin (B, D). MES cells maintaining high level of E-cadherin. We investigated the effect of TGFβ3 on the migration of cultured MES cell using the Scratch Wound Assay. MES cells expression high E-cadherin did not show any motility in the Scratch wound assay (E, G) and migration (L) in the presence of TGBβ3. Control MES cells treated with the empty GFP vector showed the usual motility in the presence of TGBβ3 (F, H). In culture, once MES cells repressed E-cadherin in response to TGFβ3 (as shown in Fig. 4B), they became motile and migrated to close the wound within 48 hours (J), compared to control untreated MES cells (I). Blocking apoptosis with zVAD-fmk did not prevent cell migration (K). Transwell MES cell migration (L) assay also supported these findings of Scratch wound assay (E-K) showing that in response to TGFβ3, MES cells migrated in culture and the motility was dependent on TGFβ3. And apoptosis was an independent mechanism (K, L). These results support the notion that repression of E-cadherin facilitates MES migration and that cell migration and apoptosis are not dependent.

TGFβ3 induces cell cycle arrest (Fig. 6)

Fig. 6. MES cells undergo TGFβ3 induced cell cycle arrest.

MES cells grown in culture were treated with Aphidicolin (6μM) for 16 hours, which blocks DNA synthesis to synchronize all MES cells at G1 phase (A). Once synchronized, MES cells were released from the block for 30 mins., treated with TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) added every 24 hours for 3 days, collected every 12 hours of treatment, fixed with 70% ethanol (−20°C) and FACSArray was done to evaluate cell cycle status. MES cells treated with TGFβ3 failed to advance to the next phases (S, G2 and M) and remained stagnant at G1. MES cells began to die and showed apoptosis as early as 24 hours gradually reaching to 23% by 72 hours without undergoing any cell cycle progression (B-F). In contrast, TGFβ3 untreated cell (control), twice progress through all phases of cell cycle (bottom panel, G-L).

As TGFβ is a potent inducer of cell cycle arrest, we investigated if TGFβ3 causes cell cycle arrest in the MES cells. Here we showed that MES cells underwent cell cycle arrest almost immediately after TGFβ3 treatment, prior to migration and apoptosis. All MES cells were synchronized to G1 phase (with Aphidicolin 6.0μM). G1 phase-synchronized MES cells showed cessation of the cell cycle almost immediately in response to TGFβ3 signaling and showed that nearly all (98%) MES cells to remain at the G1 state (A). TGFβ3 completely halted MES cell progression through next phases of the cell cycle. At no point did MES cells advance to the next (S, G2, M) phases of the cell cycle (A-F). As MES cells failed to progress through cell cycle, later MES cells began to die with 2.38% dead cell by 48 hours (D) and this percentage increased to 23.33% by 72 hours (F). However, TGFβ3 untreated control MES cells showed successful progression through all phases of cell cycle (G-L).

Apoptosis is an integral but late event in MES cells (Fig. 7)

Fig. 7. TGFβ3 promotes MES cell to undergo apoptosis.

MES cells grown in culture to 80% confluency were treated with TGFβ3. Nucleic acid dyes, C12-resazurin at 488nm and Sytox Red at 633nm excitation show “Live” (P2) and “dead” (P1) cells, respectively. The figures show cell cycle arrested cells in pink (P4) and debris in blue (P3). Within 12 hours of TGFβ3 treatment, MES cells began to cease proliferating and undergo cell cycle arrest (P4) and the number of cell cycle arrested MES cells continued to increase over time. Dead cells (P1) began to appear at 60 hours of treatment and by 72 hours, the number of “dead cells” reached nearly 33% of the total MES cells with the remaining being “dying” cells. Untreated control cell (bottom panel), in contrast, remain live and viable (P2) as late as 72 hours.

Next we examined, in addition to cell migration (as shown in Figs. 3, 4 and 5) and cell cycle arrest (Fig. 6) whether TGFβ3 also regulates MES cell death. We investigated the status and timing of the induction of apoptosis in response to TGFβ3. We demonstrated that MES cells treated with TGFβ3 showed the first evidence of apoptosis after 60 hours in culture, following cell migration (as shown in Fig. 3C). The time course of apoptosis was more accurately shown by FACSArray analysis with the incorporation of Sytox red (dead cells) and C12-resazurin (live cells). In the beginning (0 hour) of the MES in culture, majority (98.5%) of the cells were live and viable as shown by green spots (P2). Within 12 hours of TGFβ3 treatment, even as some of the MES cells continued to grow (P2), 22% MES cell ceased to proliferate and undergo cell cycle arrest (Pink, P4). With ongoing TGFβ3 treatment, MES cells continued to increased the number of cells those underwent cell cycle arrest (P4 at 24, 48 and 60 hours). However, a small percentage (11%) of MES cells were apoptotic (Red, P1) by 60 hours, while most of the cells (83%) were still under cell cycle arrest. By 72 hours, a significant fraction (∼33%) of the MES cells were dead (P1) with very little debris (Blue, P3). In control, untreated MES cells at 72 hours, cells were mostly (95%) live (P2) with only 4.8% were non-proliferating (P4), 3% apoptotic (P1) and 1% debris (P3). These FACSArray studies allowed us to identify not only the cell proliferation and apoptosis but also precise percentage cells undergoing these changes were also possible, which otherwise is not feasible in in vivo or in organ culture conditions.

In vivo, apoptosis is also a late phenomenon during MES disintegration (Fig. 8)

Fig. 8. Apoptosis during MES disintegration.

Mouse palates from 17dpc embryos showed TUNEL positive cells in the developing palates. Double immunofluorescences labeled TUNEL-FITC positive apoptotic cells were present at the remnants of epithelial cells of the oral-palatine triangular regions in near confluent palate (A, arrow). Rhodamine conjugated E-cadherin antibody was used to demarcate MES for accurate localization of the apoptotic cells. Biotin/Streptavidin-HRP/DAB labeled TUNEL positive remaining apoptotic MES cells were seen in the naso-palatine triangle (B). In MES cell culture, TUNEL positive cells (Biotin/Streptavidin-HRP/DAB labeled) are only seen 72 hours after TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) treatment (D, arrow). No TUNEL positive cells were seen in the untreated cells (C). MES cells were counter stained with H&E for detailed morphology (C, D).

To investigate the late induction of apoptosis shown by FACArray (Figs 6 and 7) are compatable to in vivo, we showed similar late apoptotic event by the presence of TUNEL positive cells in developing palate. At 17dpc, a few remaining MES cells were TUNEL positive (white arrow, A, fluorescent labeled and black arrow, B, avidin-biotin labeled) at the oral and nasal triangular regions of the developing palate. We also tested for apoptotic cells in MES cells in culture, and found that at 72 hours post TGFβ3 treatment, MES cells showed TUNEL positive cells (D, arrow) but untreated cells were not TUNEL positive (C). In accord with results from Figs. 6 and 7, results in Fig. 8 demonstrated that apoptosis was a late event in MES cell disintegration both in vitro and in vivo.

Cell cycle arrest and apoptotic markers are induced by TGFβ3 (Fig. 9)

Fig. 9. Cell cycle arrest and apoptosis markers induced by TGFβ3.

Upon TGFβ3 treatment, Protein expression of the cell cycle arrest markers p15, p21 and p27 gradually increased from 12 hours to strong expression at 72 hours with no cell proliferation maeker, PCNA expression (A), Caspase 9 and 3 showed gradually increased expression from 36 to 72 hours (B). In response to TGFβ3, MES cells showed higher expression cleaved Caspase 3 (17 and 19 kDa) at 60 and 72 hours compared to earlier time points (C). Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 and pro-apoptotic Bax protein expression was inversely proportional. BCL-2 showed high expression at 24 hours of TGFβ3 treatment but gradually decreased. Bax on the contrary showed very limited expression until 48 hours with increased expression at 72 hours (D). All untreated control (UN) experiments were done using the same method as treated but the results shown are from 48 hours as this is the time point when all proteins are expressed mostly. (A, B, C and D).

We next studied the expression of established markers of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in the MES cells. We found that MES cells expressed increased amounts of cell cycle arrest proteins p15, p21 and p27 in a time dependent manner from 12 to 72 hours in response to TGFβ3 (H). In contrast, the cell proliferation marker, PCNA was not detected (A). Caspase 9 and 3, protein inducers of apoptosis, were expressed but increased at 36 hours and had high expression at 72 hours (B). Activation of caspase-3 requires proteolytic processing of its inactive zymogen into fragments resulting from cleavage adjacent to Asp175. Caspase 3 was cleaved (Asp175) into 17 and 19 kDa fragments in response to TGFβ3 and showed a higher expression at 60 and 72 hours (C). Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 was expressed early but gradually decreased from 12 to 72 hours and pro-apoptotic Bax showed expression at 48 hours and later (D). These results demonstrate that cell cycle arrest markers (p15, p21 and p27) are expressed early, the apoptotc markers (Caspase 3, 9, cleaved Caspase 3) appear late confirming the earlier results (Figs. 6, 7 and 8) that cell cycle arrest is an early event and apoptosis is late.

TGFβ3 generates two types of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis (Fig. 10)

Fig. 10. MES cells undergo DNA fragmentation during apoptosis.

MES cells in culture undergo both High Molecular Weight, (HMW) −47kbp (A) and Low Molecular Weight (LMW) 100-700bp (C) DNA fragmentation in response to TGFβ3 that occurs in a time dependent manner at 60 and 72 hours respectively. And they are also dose sensitive as higher concentrations of exogenous TGFβ3 induce a higher degree of fragmentation (B, D). All untreated control (UN) experiments were done using the same method as treated but without TGFβ3 addition and the results from only 72 hours are shown in the figures.

DNA fragmentation is an essential feature of apoptosis. But the size of the DNA fragments can indicate whether the cell death is Caspase dependent or not. We found that DNA collected from TGFβ3 treated and untreated MES cells showed both high (A) and low (C) molecular weight DNA fragmentation in response to TGFβ3. Large size DNA fragmentation (at 60 hours, A) precedes the oligo fragmentations pattern (72 hours, C). Moreover, the extent of DNA fragmentation is dose-dependent with TGFβ3 concentration (B, D). It is noteworthy that Caspase dependent apoptosis generates LMW or oligo DNA fragments whereas HMW DNA fragmentation is the result of Caspase independent apoptosis (Bahi et al., 2006). These results demonstrated that both Caspase dependent and Caspase independent pathways were functional in MES cell apoptosis induced by TGFβ3.

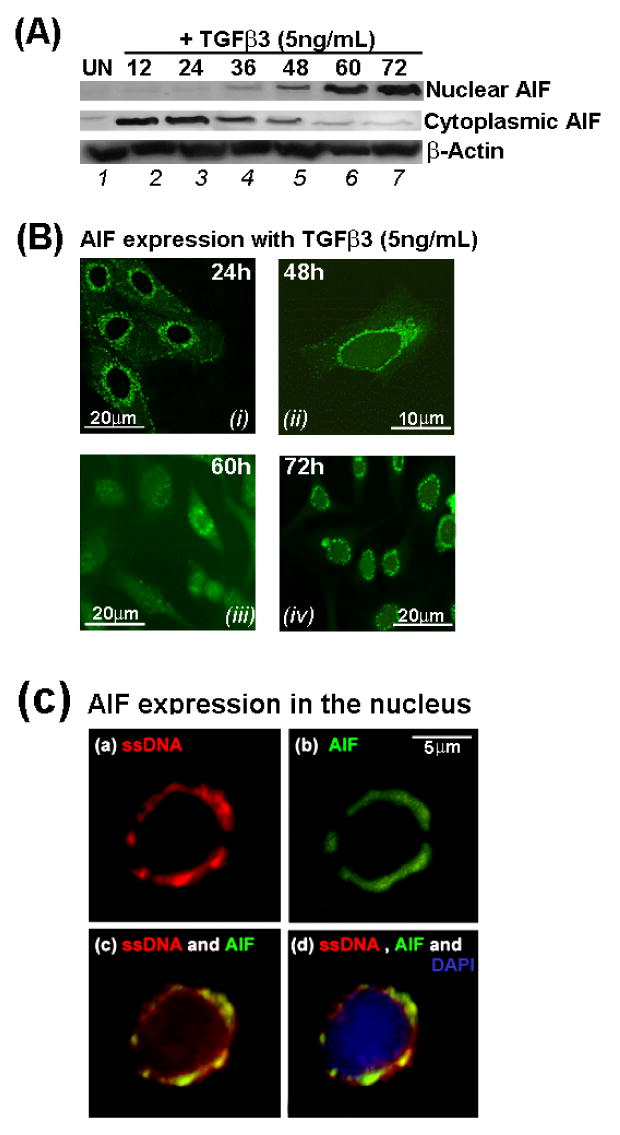

Translocation of Caspase independent apoptotic protein, Apoptotic Inducing Factor (AIF) into the MES cell nucleus by TGFβ3 (Fig. 11)

Fig. 11. Apoptotic Inducing Factor, AIF protein expression and its nuclear localization.

In response to TGFβ3 signaling, AIF protein expression remained cytoplasmic in the MES cells in the first 36 hours of TGFβ3 treatment (A, lanes 2, 3 and 4) and gradually the protein translocated into the nucleus showing low expression of AIF protein the nucleus beginning at 36 hours (lane 4) and expression gradually increased (lanes 4, 5) and reach a peak by 60 hours (A, lanes 6, 7). Similarly, exact localization of AIF protein expression was confirmed by immunofluoroscene and in accord with immunoblot results, immunofluoroscene results also showed punctate mitochondrial AIF expression at 24 (B, i) and 48 hours (B, ii). AIF protein gradually diffused in the cytoplasm translocated into the nucleus (60 hours, B, iii) and eventually showed complete nuclear by 72 hours (B, iv) expression in the MES cells. Additionally, MES cells at 60 hours showed increased AIF expression recognized by fluorescein conjugated anti-AIF monoclonal antibody in the nucleus (C, b and c) which co-localized with Rhodamine-conjugated anti single stranded (ss) DNA monoclonal antibody (C, a and c) and nucleus was stained with DAPI (C, d). Each bar value, as stated, represents the size and magnification of the image.

The mitochondrial protein AIF is an important executor of cell death when translocated into the nucleus (Ekert and Vaux, 2005). Nuclear localization of AIF protein is a crucial evidence to support functional Caspase independent apoptosis. Our results showed that in response to TGFβ3 signaling AIF expression was limited to the cytoplasm of the MES cells early from 12 to 36 hours and gradually showed reduced cytoplasmic expression post 36 hours. As cytoplasmic AIF protein translocated into the nucleus, AIF expression showed increased expression by 72 hours in the nucleus by which stage there were no or limited cytopalsmic AIF expression (A). Similarly, to identify the exact localization of AIF within the cellular compartments, we demonstrated by immunofluoroscene staining that AIF showed punctuate mitochondrial expression by 24 hours when cells were still adhered (B, i) and even when MES cells began to acquire migratory phenotype (B, ii). AIF expression was diffused throughout the cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus by 60 hours of TGFβ3 treatment (B, iii). By 72 hours, most of the AIF was nuclear with no or limited cytoplasmic or mitochondrial expression (B, iv). To demonstrate that nuclear localization of AIF (C, b and c) was indeed DNA bound, we also showed that AIF was co-expressed with single stranded (ss) DNA in the nucleus (C, a and c).

Discussion

Although cleft palate is not life-threatening, functions such as feeding, digestion, speech, middle-ear ventilation, hearing and respiration are disrupted due to distorted facial/dental development. Consequently, cleft palate can lead to considerable emotional, psychosocial, and learning problems. TGFβ signaling contributes to development from gastrulation to the completion of organogenesis (Boyer et al., 1999; Cui and Shuler, 2000; Dudas and Kaartinen, 2005; Wakefield et al., 2001) including palate development (Ferguson, 1988; Fitzpatrick et al., 1990). Population-based candidate-gene studies identified TGFβ3 as a candidate gene for human non syndromal cleft palate (Jugessur and Murray, 2005; Mitchell et al., 2001; Murray and Schutte, 2004; Vieira et al., 2003). Treatment of mouse palates with TGFβ3 antisense oligos prevents palate development (Taya et al., 1999), and most significantly, palates fail to develop in TGFβ3 null mice (Martinez-Alvarez et al., 2000; Proetzel et al., 1995) resulting in cleft palate. Cell migration and apoptosis are highly conserved and fundamental processes that govern morphogenesis (Hay, 1995; Vaux and Korsmeyer, 1999) and recent studies have shown that TGFβ3 causes cell migration or apoptosis as mechanisms of MES disintegration resulting in confluent palate. We also found that apoptosis does play a role in generating complete and successful palatal confluency (Fig. 1F). While in vivo and in vitro evidence overwhelmingly suggests the essential role of TGFβ3 in palatal MES disintegration, how these epithelial cells respond to TGFβ3 signaling and undergo cellular changes is in most part unknown and remained to be investigated.

Our research combines our interests in palate development and TGFβ-mediated cell migration and apoptosis to study the role of TGFβ signaling in the disintegration of palatal MES epithelium, a necessary step in palate development. Early studies aimed at understanding how MES cells respond to TGFβ signals were hampered by the limitations of an in vivo system. We have now developed a MES cell culture system to facilitate studies of the signaling mechanisms that drive palatal development. Here, we demonstrate that three distinctly different, yet chronological MES cellular events - cell cycle arrest, cell migration and apoptosis that contribute to the complete palatal confluency in response to TGFβ3 signaling. Although apoptosis follows cell migration, these two events are independent and the cell cycle arrest precedes both migration and apoptosis (Fig. 3 E-H and Fig. 5 K, L). These findings are essential for a better understanding of the mechanism of palate development and to potentially preventing clefting. However, it is will be intriguing to explore what controls the morphogenetic decision made by MES cells as they switch from cessation of cell cycle to convergent migratory phenotype to apoptosis.

TGFβ3 induces palatal MES cell cycle arrest

TGFβ has multiple roles including being a potent growth inhibitor of epithelial cells and has been associated with effects on G1 phase cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and CDK inhibitors (Pardali et al., 2005; Takahashi et al., 2004; Vega et al., 2004) and induces a growth inhibitory response via p21 and p15 (Matsuyama et al., 2003). The cessation of cell cycle is a key regulator of signals that effects on multiple cell processes and usually preced to cell migration and apoptosis (Boehm and Nabel, 2001; Bonneton et al., 1999). A recent study by Donovan et al., (2002) used mouse mammary epithelial cells to show that cyclin D1, CDK4 and cyclin A were down regulated and that the cell cycle inhibitors p15, p21 and p27 were up regulated by TGFβ treatment. As described very recently by Moreno-Bueno et al., (2006) that other than repressing E-cadherin, several transcription factors induced by TGFβ may have multiple roles and simultaneously induce cell cycle arrest by activating p21CIP1 and p18INK4 (Locascio et al., 2002) indicating, cells programmed for migration and/or apoptosis may undergo cell cycle arrest. Before replicating DNA, cells enter the G1 phase and interpret a massive number of signals that influence cell division and cell fate. Mistakes in this process can lead to severe developmental anomaly; therefore, cell cycle arrest is a beneficial regulatory method to avoid congenital deformity.

Our results demonstrate that MES cells undergo cell cycle arrest shortly after TGFβ3 treatment as shown by FACArray (Fig. 6A-F) and cell cycle arrest marker proteins, p15, p21 and p27 are also expressed at the same time (Fig. 9A). These results suggest that cell cycle arrest is the first and foremost effect of TGFβ3 in the MES cells. Cells undergoing either transformation or apoptosis need to halt cell cycle progression to prepare cells to undergo for such changes. Apoptotic cells will have no chance to migrate therefore it is logical for MES to migrate first followed by apoptosis by two mutually exclusive TGFβ3 signaling mechanisms as it has been shown in murine hepatocytes and in other epithelial cells (Yang et al., 2006a). Thus it is likely that TGFβ induces growth arrest before cell migration and apoptosis (Coquelle et al., 2006). Since induction of cell cycle arrest by TGFβ3 precedes cell migration and apoptosis, it is likely that cell cycle arrest might be a prerequisite for both cell migration and apoptosis in the MES cells.

Cell migration is facilitated by loss of E-cadherin

In order to acquire motility and migration epithelial cells need to lose cell-cell adhesion. Here, we show that TGFβ3 represses MES cell-cell adhesion protein, E-cadherin, expression (Fig. 4B). Loss of E-cadherin by TGFβ3 facilitates MES cell migration as they express migratory proteins such as Vimentin, Fibronectin and α-SMA (Fig. 4C-F). Additionally, we demonstrated that increasing E-cadherin by retroviral infection, we can inhibit MES cell migration and motility (Fig. 5A-H, L). Therefore, in accord with our previous study (Nawshad et al., 2007), our current results support the notions that loss of E-cadherin is a prerequisite for MES migration.

Palatal MES apoptosis by TGFβ3

Two mutually exclusive events, cell migration and apoptosis are known to be brought about by TGFβ signaling (Yang et al., 2006b). However, controversies still remain and two major models have been proposed for seam degeneration: migration (Hay, 1995; Jin and Ding, 2006; Kaartinen et al., 1997; Kang and Svoboda, 2005; Lagamba et al., 2005; Lavrin and Hay, 2000; Nawshad and Hay, 2003; Pungchanchaikul et al., 2005; Shuler et al., 1992; Sun et al., 2000a; Sun et al., 2000b; Takahara et al., 2004; Takahara S, 2004; Takigawa and Shiota, 2004) or apoptosis (Cuervo and Covarrubias, 2004; Dudas et al., 2006a; Dudas et al., 2006b; Taniguchi et al., 1995; Vaziri Sani et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2006). But all agree that both aspects of palatogenesis are induced by TGFβ3. Our results showed that both migration and apoptosis are required to complete palatal confluence.

Whenever feasible, it is important to relate palatogenesis with that of the genes of apoptotic machinery with knockout murine model. Very recently, convincing results, using a Cre-Loxp-based genetic labeling system, where the expression of Cre recombinase, was driven by a cytokeratin 14 (K14) promoter (Vasioukhin and Fuchs, 2001) and R26R reporter locus was specifically activated and irreversibly labeled in the MES epithelium showed apoptosis as the only mechanism of MES disintegration (Vaziri Sani et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2006). Using similar technique, there have been contradictory results, Jin and Ding, (2006) showed only epithelial-mesenchymal transformation or EMT as the only way for MES disintegration. Thus the results show either migration (Jin and Ding, 2006) or apoptosis (Vaziri Sani et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2006) (not both) are the mechanisms of MES disintegration. To find out whether apoptosis is functionally required for seam degeneration in vivo, Jin and Ding, (2006) showed that Apaf1 deficient mice, in which Caspases 9 and 3 are inactive exhibit normal palate. These results contradict earlier finding showing lack of palatal shelves adherens (Honarpour et al., 2000) and absence of MES disintegration (Cecconi et al., 1998) in Apaf-1 knockout mice. Nevertheless, apoptosis can still take place via Apaf-1 independent manner (Susin et al., 2000) as the cells deficient in these molecules can still die (Green, 2005). Knockouts for genes of the apoptotic pathways have also been problematic. It is, however, noteworthy that some of the knockout models can demonstrate a surprisingly high degree of phenotypic variability among individual mouse lines and penetrance of the phenotype in a mixed-background colony could well be due to the presence of additional modifier loci (Doetschman, 1999).

Vaux and Korsmeyer, (1999) argue that the pathways for physiological program cell deaths occur during development may not necessarily the same those in pathological conditions and well could be independent of Caspases. Moreover, mutations of Caspase 9 and 3 caused perinatal lethality and the only organ to be abnormal is the brain (Matalova et al., 2006; Setkova et al., 2007). It raises the possibility that during palate development, apoptosis still might occur independent of Caspases. One of the candidate gene known is Apoptosis Inducing Factor (AIF), a mitochondrial protein, causes apoptosis in a Caspase independent manner upon translocation into the nucleus (Hansen and Nagley, 2003). Arnoult et al., (2002) showed that inhibition of Caspases can still activate AIF to cause apoptosis. AIF is expressed in most of the murine developing organs (Joza et al., 2001) concomitant with the timing of palatogenesis. In addition, TGFβ is capable of activating both AIF (Dormann and Bauer, 1998) and several Caspases (Schuster and Krieglstein, 2002). AIF knockouts have extensive cell death in embryos (Brown et al., 2006).

Part of this discrepancy may stem from dual pathways for apoptosis, one being Caspase dependent by Apaf-1 and other being Caspase-independent by AIF (Hansen and Nagley, 2003). Therefore, characterizing apoptosis in MES with Apaf-1 null mice (Jin and Ding, 2006) alone is insufficient (Cecconi et al., 1998; Green, 2005). In the view of conflicting results (Jin and Ding, 2006; Vaziri Sani et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2006), we investigated further the mechanisms of apoptosis in response to TGFβ3 during MES disintegration.

Our in vivo and in vitro results imply that TGFβ3 induced apoptosis is an integral but late fate of MES disintegration (Figs. 6 E, F, 7, 8, 9 B, C and 10). It is reasonable to have apoptotic induction late when MES cells complete migration in the developing palate. Moreover, the late increased expressions of Caspase 9 and 3 (Fig. 9B), cleaved Caspase 3 (Fig. 9C) and pro-apoptotic Bax (Fig. 9D) match closely with the in vivo advent of apoptosis (Fig. 8). Such late induction of apoptosis has also been implied with FACSArray and DNA fragmentation results (Figs. 6, 7 and 10) and the apoptotic changes that MES cells undergo at 60 hours in response to TGFβ3. DNA degradation, which is a hallmark of apoptosis, can be achieved by both Caspase dependent and Caspase independent (AIF induced) intrinsic pathways generating two different size of DNA fragments, high molecular weight (HMW) ∼50kb (AIF dependent) and low molecular weight (LMW), oligo (Caspase dependent). Both mechanisms initiate and bifurcate from mitochondria, upstream of Apaf-1, to release lethal proteins. While overwhelming evidence supports TGFβ3 induced apoptosis a late event of MES disappearance, the mechanisms of apoptosis are yet to be fully understood. Interestingly; we found late induction (60 hours) of significant HMW (∼50kb) DNA fragments, which are a sign of Caspase independent apoptosis (Bahi et al., 2006) as well LMW (oligo) fragment in response to TGFβ3 in time and dose dependent manner (Fig. 10). In response to apoptotic stimulation, concurrent to Cytochrome c for Caspase activation, AIF is also released from mitochondria and translocates into the nucleus due to its nuclear localization signal. AIF is devoid of any nuclease activity (Cande et al., 2002) so once in the nucleus, it randomly binds to the DNA (Vahsen et al., 2006), reconfigures chromatin structure, recruits Topoisomerase II to induce ∼50kb DNA fragments. AIF is implicated strongly during embryonic apoptosis (Joza et al., 2001).

Our data show that TGFβ3 induced Caspase dependent and Caspase independent mechanisms of apoptosis are functional in MES cells. AIF is a mitochondrial protein known to translocate to the nucleus during Caspase independent apoptosis where it participates in the high molecular DNA fragmentations. Moreover, to validate the role of AIF in MES cells, we examined the cellular localization of AIF in MES cells at various stages of TGFβ3 treatment by immunofluorescent staining with anti-AIF antibody. We showed that AIF protein expression shifts from cytoplasm to nucleus in response to TGFβ3 (Fig. 11 A, B). Our results also demonstrated that in response to TGFβ3, AIF protein expression gradually translocates from the mitochondria (punctuate mitochondrial localization) to the cytoplasm (diffuse cytoplasmic localization) and eventually into the nucleus (DNA bound localization) (Fig. 11B). And in the nucleus AIF localizes with ssDNA (Fig. 11C). Dual staining of AIF with ssDNA is a sensitive and specific marker for the identification of early stage of apoptosis that have HMW DNA fragmentations (Zhao et al., 2003). These results suggest that AIF participates in the DNA fragmentation during MES apoptosis. Therefore, we predict that induction of apoptosis in the MES cells by TGFβ3 is both Caspase dependent and Caspase independent. Further research might shed light into the rationale and mechanisms of dual apoptotic methods in palatal MES cells. We showed that following MES cell migration, TGFβ3 exerts its effects by activating pro-apoptotic factors that induce both Caspase dependent and independent apoptosis to complete palatal confluence.

During the process of palate development, the MES is formed upon adhesion of the palatal shelves. The sedentary seam epithelial cells then undergo significant phenotypical changes from migratory to apoptotic cells during palatogenesis. TGFβ3 signals are interpreted by complex intracellular circuits, resulting in coordinated changes in gene expression and cellular morphogenesis to induce cell migration and death. Our data demonstrates that TGFβ3 induces cell cycle arrest, cell migration and apoptosis in primary MES and these integrated processes transform the palatal seam epithelia into a single confluent palatal mesenchymal structure. Our results suggest that apoptosis is independent of migration. Moreover, MES cells also undergo cell cycle arrest prior to cell migration. We showed an in vitro model of chronological events that take places during palate development by TGFβ3 signaling in the context of palatal MES disintegration. While, TGFβ3 can signal via multiple pathways to activate many transcription factors to generate several cellular outcomes, such as cell cycle arrest, migration and apoptosis, we predict that timing, level and length of signals and activation of downstream molecules are responsible for such diverse phonotypical effects in the same cell type by same activator (TGFβ3). In future we will determine the genes, transcription factors and cellular changes that are necessary for palatogenesis and address how TGFβ3 signaling selectively activates what is required for migration and apoptosis and represses which are not in the formation of confluent palate.

Supplementary Material

We examined the expression of TGFβ3 ligand in palates (in vivo) as well as organ culture and MES cell culture conditions (in vitro). For in vivo palatal MES seam mRNA, embryonic palates were collected at 14.5 dpc which is labeled as “0” hour and every 12 from hours thereafter from 15.0, 15.5, 16.0, 16.5, 17.0, 17.5 and 18.0 dpc embryos. mRNA was collected using Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) as described previously by Nawshad et al, (2004). For organ culture, palatal shelves were dissected from 14.0 dpc embryos and cultured in organ culture dish in vitro for 4 days in presence of exogenous TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) changed every 24 hours. mRNA was collected from paired palates every 12 hours. For mRNA from MES cell culture, primary MES cells were collected from paired palatal shelves from 14.0 dpc as described in the “Materials and Methods” section and cultured for 4 days and mRNA was collected every 12 hours. The result showed that TGFβ3 mRNA is expressed in increased amount at 14.5 dpc (0) and remain high till 16.5 dpc (48) and gradually tapered down by 18.0 dpc (96), however, as palatal shelves are collected at 14.0 dpc and cultured for organ culture or primary MES cell culture in vitro, TGFβ3 mRNA expression in both these in vitro cases were significantlu lower and only briefly express at 0 hours which is 14.0 dpc. There were no detectable TGFβ3 mRNA expression after that. These results suggest that TGFβ3 failed to express in significant amount in in vitro culture condition whereas in vivo TGFβ3 expression remained high. Therefore, exogenous TGFβ3 is required to mimin in vivo condition in in vitro cultures for both palatal shelves and primary MES cells. β-Actin was used as control for all with identical results, but shown only one.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jim K. Wahl III, Keith R. Johnson, Tom Petro and Gregory Oakley for their valuable suggestions and providing us with reagents. This work was supported by RR018759 NIH-CoBRE for the Nebraska Center for Cellular Signaling (to M. J. Wheelock) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arnoult D, Parone P, Martinou JC, Antonsson B, Estaquier J, Ameisen JC. Mitochondrial release of apoptosis-inducing factor occurs downstream of cytochrome c release in response to several proapoptotic stimuli. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:923–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahi N, Zhang J, Llovera M, Ballester M, Comella JX, Sanchis D. Switch from caspase-dependent to caspase-independent death during heart development: essential role of endonuclease G in ischemia-induced DNA processing of differentiated cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22943–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm M, Nabel EG. Cell cycle and cell migration: new pieces to the puzzle. Circulation. 2001;103:2879–81. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.24.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneton C, Sibarita JB, Thiery JP. Relationship between cell migration and cell cycle during the initiation of epithelial to fibroblastoid transition. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1999;43:288–95. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1999)43:4<288::AID-CM2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer AS, Ayerinskas II, Vincent EB, McKinney LA, Weeks DL, Runyan RB. TGFbeta2 and TGFbeta3 have separate and sequential activities during epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart. Dev Biol. 1999;208:530–45. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D, Yu BD, Joza N, Benit P, Meneses J, Firpo M, Rustin P, Penninger JM, Martin GR. Loss of Aif function causes cell death in the mouse embryo, but the temporal progression of patterning is normal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9918–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603950103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cande C, Cecconi F, Dessen P, Kroemer G. Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF): key to the conserved caspase-independent pathways of cell death? J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4727–34. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi F, Alvarez-Bolado G, Meyer BI, Roth KA, Gruss P. Apaf1 (CED-4 homolog) regulates programmed cell death in mammalian development. Cell. 1998;94:727–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81732-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coquelle A, Mouhamad S, Pequignot MO, Braun T, Carvalho G, Vivet S, Metivier D, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Enrichment of non-synchronized cells in the G1, S and G2 phases of the cell cycle for the study of apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo R, Covarrubias L. Death is the major fate of medial edge epithelial cells and the cause of basal lamina degradation during palatogenesis. Development. 2004;131:15–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.00907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui XM, Shuler CF. The TGF-beta type III receptor is localized to the medial edge epithelium during palatal fusion. Int J Dev Biol. 2000;44:397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetschman T. Interpretation of phenotype in genetically engineered mice. Lab Anim Sci. 1999;49:137–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JC, Rothenstein JM, Slingerland JM. Non-malignant and tumor-derived cells differ in their requirement for p27Kip1 in transforming growth factor-beta-mediated G1 arrest. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41686–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormann S, Bauer G. TGF-beta and FGF-trigger intercellular induction of apoptosis: analogous activity on non-transformed but differential activity on transformed cells. Int J Oncol. 1998;13:1247–52. doi: 10.3892/ijo.13.6.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudas M, Kaartinen V. Tgf-beta superfamily and mouse craniofacial development: interplay of morphogenetic proteins and receptor signaling controls normal formation of the face. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005;66:65–133. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)66003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudas M, Kim J, Li WY, Nagy A, Larsson J, Karlsson S, Chai Y, Kaartinen V. Epithelial and ectomesenchymal role of the type I TGF-beta receptor ALK5 during facial morphogenesis and palatal fusion. Dev Biol. 2006a;296:298–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudas M, Li WY, Kim J, Yang A, Kaartinen V. Palatal fusion - Where do the midline cells go? A review on cleft palate, a major human birth defect. Acta Histochem. 2006b doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekert PG, Vaux DL. The mitochondrial death squad: hardened killers or innocent bystanders? Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2005;17:626–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson MW. Palate development. Development. 1988;103(Suppl):41–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.Supplement.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick DR, Denhez F, Kondaiah P, Akhurst RJ. Differential expression of TGF beta isoforms in murine palatogenesis. Development. 1990;109:585–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt OS, Krishan A. Identification of apoptotic cells by formamide-induced dna denaturation in condensed chromatin. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:369–78. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR. Apoptotic pathways: ten minutes to dead. Cell. 2005;121:671–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TM, Nagley P. AIF: a multifunctional cog in the life and death machine. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:PE31. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.193.pe31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay ED. An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat. 1995;154:8–20. doi: 10.1159/000147748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honarpour N, Du C, Richardson JA, Hammer RE, Wang X, Herz J. Adult Apaf-1-deficient mice exhibit male infertility. Dev Biol. 2000;218:248–58. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin JZ, Ding J. Analysis of cell migration, transdifferentiation and apoptosis during mouse secondary palate fusion. Development. 2006;133:3341–7. doi: 10.1242/dev.02520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joza N, Susin SA, Daugas E, Stanford WL, Cho SK, Li CY, Sasaki T, Elia AJ, Cheng HY, Ravagnan L, Ferri KF, Zamzami N, Wakeham A, Hakem R, Yoshida H, Kong YY, Mak TW, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Kroemer G, Penninger JM. Essential role of the mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor in programmed cell death. Nature. 2001;410:549–54. doi: 10.1038/35069004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jugessur A, Murray JC. Orofacial clefting: recent insights into a complex trait. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:270–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaartinen V, Cui XM, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J, Shuler CF. Transforming growth factor-beta3 regulates transdifferentiation of medial edge epithelium during palatal fusion and associated degradation of the basement membrane. Dev Dyn. 1997;209:255–60. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199707)209:3<255::AID-AJA1>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaartinen V, Voncken JW, Shuler C, Warburton D, Bu D, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-beta 3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat Genet. 1995;11:415–21. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang P, Svoboda KK. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transformation during Craniofacial Development. J Dent Res. 2005;84:678–90. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagamba D, Nawshad A, Hay ED. Microarray analysis of gene expression during epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:132–142. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavrin IG, Hay ED. Re: epithelial-mesenchymal transformation, palatogenesis and cleft palate. Angle Orthod. 2000;70:181–2. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2000)070<0181:LFOR>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locascio A, Vega S, de Frutos CA, Manzanares M, Nieto MA. Biological potential of a functional human SNAIL retrogene. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38803–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205358200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Alvarez C, Tudela C, Perez-Miguelsanz J, O'Kane S, Puerta J, Ferguson MW. Medial edge epithelial cell fate during palatal fusion. Dev Biol. 2000;220:343–57. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matalova E, Sharpe PT, Lakhani SA, Roth KA, Flavell RA, Setkova J, Misek I, Tucker AS. Molar tooth development in caspase-3 deficient mice. Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50:491–7. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052117em. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S, Iwadate M, Kondo M, Saitoh M, Hanyu A, Shimizu K, Aburatani H, Mishima HK, Imamura T, Miyazono K, Miyazawa K. SB-431542 and Gleevec inhibit transforming growth factor-beta-induced proliferation of human osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7791–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell LE, Murray JC, O'Brien S, Christensen K. Evaluation of two putative susceptibility loci for oral clefts in the Danish population. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:1007–15. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.10.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Bueno G, Cubillo E, Sarrio D, Peinado H, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Villa S, Bolos V, Jorda M, Fabra A, Portillo F, Palacios J, Cano A. Genetic profiling of epithelial cells expressing e-cadherin repressors reveals a distinct role for snail, slug, and e47 factors in epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9543–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JC, Schutte BC. Cleft palate: players, pathways, and pursuits. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1676–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI22154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawshad A, Hay ED. TGF{beta}3 signaling activates transcription of the LEF1 gene to induce epithelial mesenchymal transformation during mouse palate development. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1291–1301. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawshad A, LaGamba D, Olsen BR, Hay ED. Laser capture microdissection (LCM) for analysis of gene expression in specific tissues during embryonic epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:529–34. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawshad A, Medici D, Liu CC, Hay ED. TGFbeta3 inhibits E-cadherin gene expression in palate medial-edge epithelial cells through a Smad2-Smad4-LEF1 transcription complex. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1646–53. doi: 10.1242/jcs.003129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardali K, Kowanetz M, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Smad pathway-specific transcriptional regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21(WAF1/Cip1) J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:260–72. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proetzel G, Pawlowski SA, Wiles MV, Yin M, Boivin GP, Howles PN, Ding J, Ferguson MW, Doetschman T. Transforming growth factor-beta 3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet. 1995;11:409–14. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pungchanchaikul P, Gelbier M, Ferretti P, Bloch-Zupan A. Gene expression during palate fusion in vivo and in vitro. J Dent Res. 2005;84:526–31. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster N, Krieglstein K. Mechanisms of TGF-beta-mediated apoptosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;307:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00441-001-0479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setkova J, Matalova E, Sharpe PT, Misek I, Tucker AS. Primary enamel knot cell death in Apaf-1 and caspase-9 deficient mice. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:15–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuler CF, Halpern DE, Guo Y, Sank AC. Medial edge epithelium fate traced by cell lineage analysis during epithelial-mesenchymal transformation in vivo. Dev Biol. 1992;154:318–30. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90071-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Baur S, Hay ED. Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation is the mechanism for fusion of the craniofacial primordia involved in morphogenesis of the chicken lip. Dev Biol. 2000a;228:337–49. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Griffith CM, Hay ED. Carboxyfluorescein as a marker at both light and electron microscope levels to follow cell lineage in the embryo. Methods Mol Biol. 2000b;135:357–63. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-685-1:357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susin SA, Daugas E, Ravagnan L, Samejima K, Zamzami N, Loeffler M, Costantini P, Ferri KF, Irinopoulou T, Prevost MC, Brothers G, Mak TW, Penninger J, Earnshaw WC, Kroemer G. Two distinct pathways leading to nuclear apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2000;192:571–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara S, Takigawa T, Shiota K. Programmed cell death is not a necessary prerequisite for fusion of the fetal mouse palate. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:39–46. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.15005573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara S TT, Shiota K. Programmed cell death is not necessary prerequisite for fusion of the fetal mouse palate. International Journal of Development Biology. 2004;48:39–46. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.15005573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi E, Funato N, Higashihori N, Hata Y, Gridley T, Nakamura M. Snail regulates p21(WAF/CIP1) expression in cooperation with E2A and Twist. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:1136–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takigawa T, Shiota K. Terminal differentiation of palatal medial edge epithelial cells in vitro is not necessarily dependent on palatal shelf contact and midline epithelial seam formation. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:307–17. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041840tt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K, Sato N, Uchiyama Y. Apoptosis and heterophagy of medial edge epithelial cells of the secondary palatine shelves during fusion. Arch Histol Cytol. 1995;58:191–203. doi: 10.1679/aohc.58.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taya Y, O'Kane S, Ferguson MW. Pathogenesis of cleft palate in TGF-beta3 knockout mice. Development. 1999;126:3869–79. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahsen N, Cande C, Dupaigne P, Giordanetto F, Kroemer RT, Herker E, Scholz S, Modjtahedi N, Madeo F, Le Cam E, Kroemer G. Physical interaction of apoptosis-inducing factor with DNA and RNA. Oncogene. 2006;25:1763–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasioukhin V, Fuchs E. Actin dynamics and cell-cell adhesion in epithelia. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:76–84. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaux DL, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death in development. Cell. 1999;96:245–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri Sani F, Hallberg K, Harfe BD, McMahon AP, Linde A, Gritli-Linde A. Fate-mapping of the epithelial seam during palatal fusion rules out epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Dev Biol. 2005;285:490–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega S, Morales AV, Ocana OH, Valdes F, Fabregat I, Nieto MA. Snail blocks the cell cycle and confers resistance to cell death. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1131–43. doi: 10.1101/gad.294104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira AR, Orioli IM, Castilla EE, Cooper ME, Marazita ML, Murray JC. MSX1 and TGFB3 contribute to clefting in South America. J Dent Res. 2003;82:289–92. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield LM, Piek E, Bottinger EP. TGF-beta signaling in mammary gland development and tumorigenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2001;6:67–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1009568532177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Han J, Ito Y, Bringas P, Jr, Urata MM, Chai Y. Cell autonomous requirement for Tgfbr2 in the disappearance of medial edge epithelium during palatal fusion. Dev Biol. 2006;297:238–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Pan X, Lei W, Wang J, Shi J, Li F, Song J. Regulation of Transforming Growth Factor-{beta}1-Induced Apoptosis and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition by Protein Kinase A and Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription 3. Cancer Res. 2006a;66:8617–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Pan X, Lei W, Wang J, Song J. Transforming growth factor-beta1 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and apoptosis via a cell cycle-dependent mechanism. Oncogene. 2006b;25:7235–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Schmid-Kotsas A, Gross HJ, Gruenert A, Bachem MG. Sensitivity and specificity of different staining methods to monitor apoptosis induced by oxidative stress in adherent cells. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116:1923–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

We examined the expression of TGFβ3 ligand in palates (in vivo) as well as organ culture and MES cell culture conditions (in vitro). For in vivo palatal MES seam mRNA, embryonic palates were collected at 14.5 dpc which is labeled as “0” hour and every 12 from hours thereafter from 15.0, 15.5, 16.0, 16.5, 17.0, 17.5 and 18.0 dpc embryos. mRNA was collected using Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) as described previously by Nawshad et al, (2004). For organ culture, palatal shelves were dissected from 14.0 dpc embryos and cultured in organ culture dish in vitro for 4 days in presence of exogenous TGFβ3 (5ng/mL) changed every 24 hours. mRNA was collected from paired palates every 12 hours. For mRNA from MES cell culture, primary MES cells were collected from paired palatal shelves from 14.0 dpc as described in the “Materials and Methods” section and cultured for 4 days and mRNA was collected every 12 hours. The result showed that TGFβ3 mRNA is expressed in increased amount at 14.5 dpc (0) and remain high till 16.5 dpc (48) and gradually tapered down by 18.0 dpc (96), however, as palatal shelves are collected at 14.0 dpc and cultured for organ culture or primary MES cell culture in vitro, TGFβ3 mRNA expression in both these in vitro cases were significantlu lower and only briefly express at 0 hours which is 14.0 dpc. There were no detectable TGFβ3 mRNA expression after that. These results suggest that TGFβ3 failed to express in significant amount in in vitro culture condition whereas in vivo TGFβ3 expression remained high. Therefore, exogenous TGFβ3 is required to mimin in vivo condition in in vitro cultures for both palatal shelves and primary MES cells. β-Actin was used as control for all with identical results, but shown only one.