Abstract

Phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic tyrosine residues of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) upon binding of EGF induces recognition of various intracellular signaling molecules, including Grb2. Here, the reaction kinetics between EGFR and Grb2 was analyzed by visualizing single molecules of Grb2 conjugated to the fluorophore Cy3 (Cy3–Grb2). The plasma membrane fraction was purified from human epithelial carcinoma A431 cells after stimulation with EGF and attached to coverslips. Unitary events of association and dissociation of Cy3–Grb2 on the EGFR in the membrane fraction were observed at different concentrations of Grb2 (0.1–100 nM). The dissociation kinetics could be explained by using a multiple-exponential function with a major (>90%) dissociation rate of 8 s−1 and a few minor components, suggesting the presence of multiple bound states. In contrast, the association kinetics could be described by a stretched exponential function, suggesting the presence of multiple reaction channels from many unbound substates. Transitions between the unbound substates were also suggested. Unexpectedly, the rate of association was not proportional to the Grb2 concentration: an increase in Cy3–Grb2 concentration by a factor of 10 induced an increase in the reaction frequency approximately by a factor of three. This effect can compensate for fluctuation of the signal transduction from EGFR to Grb2 caused by variations in the expression level of Grb2 in living cells.

Keywords: EGFR, signal transduction, tyrosine phosphorylation

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a transmembrane receptor protein embedded in the plasma membrane of many types of cells and is responsible for cell proliferation, movement, and carcinogenesis (1, 2). Binding of the extracellular ligand, epidermal growth factor (EGF), activates EGFR to induce mutual phosphorylation of the tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain (3–5). The phosphotyrosine residues are then recognized by various cytoplasmic proteins, including Grb2 (6), Shc (7, 8), and PLC-γ (9, 10), which transmit the external EGF signals into the cytoplasm. Grb2 is an adaptor protein that consists of one Src homology (SH) 2 domain with two SH3 domains on both sides (6). Grb2 has no enzymatic activity, but its SH2 domain recognizes the phosphotyrosine residues of activated EGFR, and the SH3 domains bind to a Ras GTP exchange factor, Sos (11–15). Thus, Grb2 links activated EGFR to downstream signaling molecules to induce gene expression and morphological changes in cells.

This study focused on the kinetic properties of the recognition between EGFR and Grb2. To gain an understanding of the signal flows in cells, it is important to clarify the association and dissociation kinetics between signaling molecules. Recognition between phosphopeptides derived from EGFR and whole molecules of Grb2 have been studied using surface plasmon resonance (16, 17) and tryptophan fluorescence (18), which identified dissociation equilibrium constants. However, rate constants of the reaction were directly measured only for dissociation between an EGFR peptide and a Grb2/Sos complex (16), and association rates were not directly measured at all. Moreover, none of the studies used an intact EGFR molecule. It is indispensable to reveal the reaction rate constants between intact forms of EGFR and Grb2. The cytoplasmic domain of EGFR contains >500 amino acids, and it has been shown that this domain causes a conformational change upon phosphorylation of tyrosine resides (19), which could affect interactions with cytoplasmic binding proteins.

Owing to conformational changes in EGFR upon tyrosine phosphorylation, the kinetic properties between Grb2 and intact EGFR could be complex. Single-molecule measurement is a powerful experimental technique used to study the details of complex kinetics. Measurements of the distributions and temporal fluctuations in the duration of individual molecular recognition processes using the single-molecule technique have revealed the static and dynamic disorders (20–23) and memory landscapes (24, 25) of enzymatic reactions, as well as dynamic polymorphisms of protein structures (26–28). In living cells, single-molecule measurements have even been used to clarify spatially inhomogeneous kinetics in receptor–ligand (29) and protein–protein (30) dissociations, and to identify previously unknown reaction intermediates (31).

In this article, individual detachments and attachments of fluorescently labeled Grb2 to intact EGFR molecules in the plasma membrane fraction were observed in vitro by using single-molecule imaging to reveal the association and dissociation kinetics between EGFR and Grb2. The results suggest the presence of multiple states in both bound and unbound forms for the first time. Unexpectedly, the characteristic time of the association reaction was abnormally dependent on the Grb2 concentration.

Results

Single-Molecule Observation of the Recognition Between Activated EGFR and Cy3–Grb2.

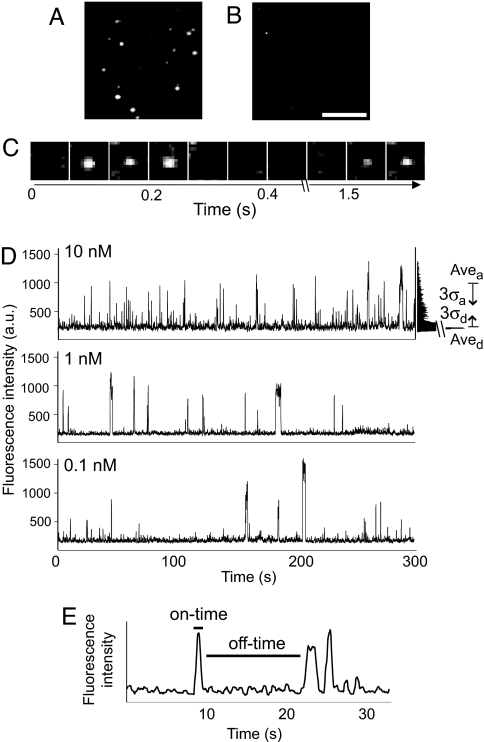

The plasma membrane fraction was purified from A431 human carcinoma cells after stimulation with EGF. Tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-EGFR and phosphotyrosine antibodies [supporting information (SI) Fig. 6]. When the plasma membrane fraction was attached to a coverslip and incubated with Grb2 conjugated to the fluorophore Cy3 at the amino terminus (Cy3–Grb2), repeated binding and release of fluorescent Cy3 were observed at the same positions on the glass surface (Fig. 1 A and C and SI Movie 1). In the nonstimulated plasma membrane fraction, such repeated binding of Cy3–Grb2 was hardly observed (Fig. 1B), and the total binding duration represented only 2.8% of that for the stimulated membrane fraction. These results suggest specific binding of Cy3–Grb2 to activated EGFR molecules.

Fig. 1.

Single-molecule observation of interactions between EGFR and Cy3–Grb2. (A and B) Cy3–Grb2 bound to the plasma membrane fraction with (A) and without (B) EGF stimulation. The fluorescence intensity of each spot represents the frequency of Cy3–Grb2 binding because images were accumulated during 1 min. (Scale bar: 5 μm.) (C) Repeated binding and release of Cy3–Grb2 were observed at a single site on the stimulated membrane fraction (see SI Movie 1). (D) Changes in the fluorescence intensity at single binding sites plotted against time. A histogram of the fluorescence intensity is shown on the right of the plot at 10 nM Cy3–Grb2. The averages and σ value are used to determine thresholds for the on and off states (see Materials and Methods). (E) The on- and off-time for each event were determined from the fluorescence intensity.

Changes in the fluorescence intensity at individual binding sites were measured for 18 min at various concentrations of Cy3–Grb2 (Fig. 1D). The fluorescence intensity of the Cy3–Grb2 spot varied for each binding event, but its distribution was similar to that of single molecules of Cy3 observed under the same conditions. Simultaneous binding of multiple Cy3–Grb2 molecules at the same binding site was rarely observed. The frequency of the binding events increased as the concentration of Grb2 in the solution increased. Thus, recognition between EGFR and Grb2 depending on the activation (tyrosine phosphorylation) of EGFR was observed in single molecules. The durations from the onset of association to the dissociation of single Cy3–Grb2 molecules (on-times) and from the dissociation of a Cy3–Grb2 molecule to the association of the next Cy3–Grb2 molecule (off-times) were measured for further analysis (Fig. 1E). The effects of bleaching and blinking of Cy3 on the on- and off-times were minimal because the decay time for bleaching was 15 s and blinking occurred only once in 147 s under the same excitation conditions. These time constants were much longer than the on-times.

Dissociation Kinetics Between EGFR and Grb2.

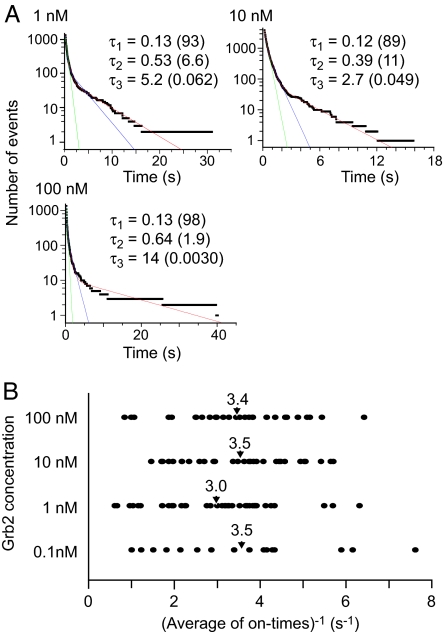

Dissociation between EGFR and Grb2 can be described by conventional exponential kinetics, independent of the Grb2 concentration. Cumulative histograms of the on-times were fitted by multiple exponential functions. The fittings were significantly improved with an increasing number of exponential components up to three, but the use of four components did not result in further improvement (SI Table 3). Therefore, there seem to be at least three binding states between EGFR and Grb2 (Fig. 2A). The major component (>89%) showed the fastest dissociation rate constant, which was 8.1–7.5 s−1 (Table 1). The second component accounted for 2–11%, for which the rate constant was 1.6–2.6 s−1. The third component was minor but should not be neglected because slow dissociations were the most distinct events in the observation (SI Fig. 7). The results were essentially the same for all Grb2 concentrations. These results suggest that EGFR and Grb2 have multiple binding states with different dissociation rate constants, but most of the dissociations took place from the major binding state.

Fig. 2.

Dissociation kinetics. (A) Cumulative histograms of the on-times for each concentration of Grb2. The histograms were fitted with a single (green) and a sum of two (blue) or three (red) exponential functions. τ1–τ3 (in s) are the time constants in the fitting to the three-component multiple-exponential function. Numbers in parentheses are percentages of each fraction. (B) Distributions of the inverse of the average on-times at individual binding sites. The average of every binding site for each concentration of Grb2 is indicated by an arrowhead.

Table 1.

Parameters for dissociation kinetics between EGFR and Grb2

| [Grb2], nM | k1, s−1 | Fraction, % | k2, s−1 | Fraction, % | k3, s−1 | Fraction, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.5 | 93 | 1.9 | 6.6 | 0.19 | 0.062 |

| 10 | 8.1 | 89 | 2.6 | 11 | 0.37 | 0.049 |

| 100 | 7.6 | 98 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 0.070 | 0.0030 |

The dissociation rate constants (k1–k3) and fractions were obtained by fitting cumulative histograms of the on-times (Fig. 2A) to the three-component multiple-exponential function.

The distribution of the dissociation rate for individual binding sites (static disorder) was examined (Fig. 2B). Owing to the small numbers of binding events at single binding sites, especially for low concentrations of Grb2, analysis using multiple exponential fitting was impossible for single binding sites. Therefore, the inverse of the average on-time was calculated for each site as an indication of the dissociation rate. The distributions of this value were similar for all Grb2 concentrations examined: at every concentration, the average was ≈3.4 s−1 and the width of the distribution was smaller than one order of magnitude. Thus, large differences in the dissociation rate (by a factor of 20–110) observed from multiple exponential fitting of the on-time distributions (Table 1) cannot be explained in terms of static disorder at the individual binding sites.

Association Kinetics Between EGFR and Grb2.

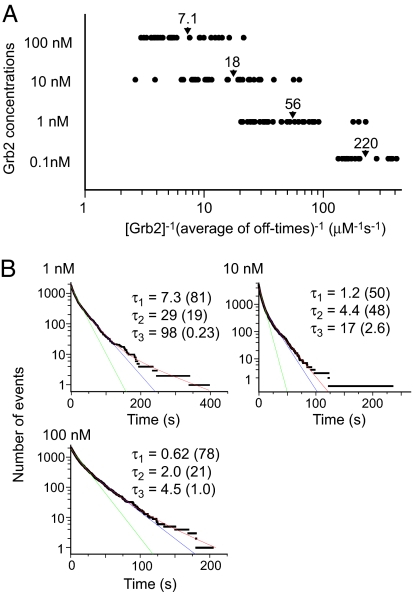

Different from the average on-times, the average off-times for individual binding sites showed a curious dependence on the Grb2 concentration. The inverse of the average off-time after multiplication by the Grb2 concentration, which has the same dimension as the second-order association rate constant, varied with the Grb2 concentration (Fig. 3A); as the Grb2 concentration decreased, association occurred relatively faster. The distributions of this indication suggest that the association rate gradually changes with the Grb2 concentration. This phenomenon was not caused by irreversible destruction of the binding sites by high concentrations of Grb2 (SI Fig. 8).

Fig. 3.

Association kinetics. (A) Distributions of the inverse of the average off-times at individual reaction sites divided by the Grb2 concentration. The average of every binding site for each concentration of Grb2 is indicated by an arrowhead. The left ends of the distributions were limited to avoid nonspecific bindings (see Materials and Methods). (B) Cumulative histograms of the off-times for each concentration of Grb2. The histograms were fitted with a single (green) and a sum of two (blue) or three (red) exponential functions. τ1–τ3 (in s) are the time constants in the fitting to multiple exponential functions. Numbers in parentheses are percentages of each fraction. τ1–τ3 at 100 nM Grb2 (10 nM Cy3–Grb2 mixed with 90 nM nonlabeled Grb2) are the normalized values assuming the same reaction rate for Cy3-labeled and nonlabeled Grb2.

Cumulative histograms of the off-times for each Grb2 concentration can be fitted with the sum of three exponential functions (Fig. 3B). However, the rate constants obtained from the multiple-exponential kinetics were distributed widely over three concentrations of Grb2 (Table 2). In addition, the fractions of each component were irregular. Thus, it is hard to obtain a unified view of the reaction based on the exponential kinetics. In general, the (apparent) second-order rate constant decreases with increasing Grb2 concentration. The results of global fitting indicate that four or more components were required for multiple-exponential kinetics to describe the association reaction (SI Fig. 9).

Table 2.

Multiple-exponential kinetics for the association between EGFR and Grb2

| [Grb2], nM | k1, μM−1·s−1 | Fraction, % | k2, μM−1·s−1 | Fraction, % | k3, μM−1·s−1 | Fraction, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 140 | 81 | 35 | 19 | 10 | 0.23 |

| 10 | 84 | 50 | 23 | 48 | 5.9 | 2.6 |

| 100* | 16 | 78 | 4.9 | 21 | 2.2 | 1.0 |

The association rate constants (k1–k3) and fractions were obtained by fitting histograms of the off-times (Fig. 3B) to the three-component multiple-exponential function.

*The best-fit values for k1–k3 were divided by 10 to normalize the concentration of Cy3–Grb2.

The association reaction was analyzed by using exponential kinetics for individual sites that showed >60 binding events at 10 nM Cy3–Grb2 (29 reaction sites). One-third (9/29) of the histograms were fitted to a single-exponential function (SI Fig. 10A left) and the others were fitted to a sum of two exponential functions (SI Fig. 10A right). The second-order association rate constants obtained from fitting were widely distributed without evidence of multiple peaks (SI Fig. 10B). Thus, it is highly probable that the association rate was different for every reaction site and could change with time, even at single reaction sites. This result negates the possibility that there were a few defined pathways for association and supports the model of association reaction assuming drifting of the system over multiple substates.

A stretched exponential function (see Materials and Methods) is a candidate for describing reaction kinetics with broad time scales. Using this kinetic approach, all of the histograms for different Grb2 concentrations showed similar values of the exponent (α) of ≈0.50 (0.41–0.56; Fig. 4). This means that the stretched exponential function provides a better representation of the reaction mechanism than the multiple-exponential function. Again, the time constant (τ) varied but was not inversely proportional to the Grb2 concentration; the association reaction became relatively slower with increasing Grb2 concentration.

Fig. 4.

Stretched exponential kinetics of the association events. Cumulative histograms of the off-times as shown in Fig. 3B were fitted with a stretched exponential function. Red lines are the results of fitting by floating both the time constant τ (in s) and the exponent α. Blue lines are the results of fitting with α fixed to 0.5 and floating the time constant τ′ (in s). τ and τ′ for 100 nM Grb2 are normalized values assuming the same reaction rate for Cy3-labeled and nonlabeled Grb2.

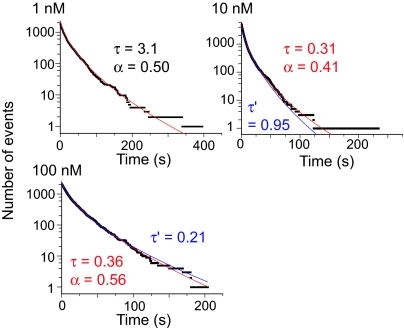

Dissociation Equilibrium Constant Between EGFR and Grb2.

The apparent dissociation equilibrium constant between activated EGFR and Grb2 for each reaction site was calculated from the ratio of total on- and off-times (Fig. 5). The on-times were independent of the Grb2 concentrations, but the off-times multiplied by the Grb2 concentration increased with increasing Grb2 concentration (Figs. 2B and 3A). As a result, the dissociation constants increased with increasing Grb2 concentration; i.e., the affinity between activated EGFR and Grb2 decreased approximately by a factor of three as the Grb2 concentration increased by a factor of 10.

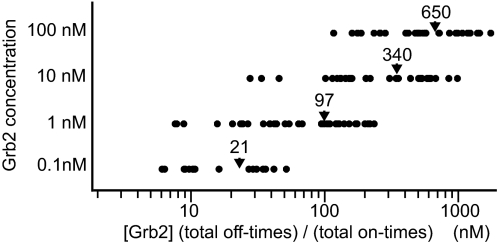

Fig. 5.

Distribution of the dissociation equilibrium constants. The ratio of the total off-times to the total on-times was calculated for individual reaction sites and multiplied by the Grb2 concentration. The average over every reaction site for each concentration of Grb2 is indicated by an arrowhead.

Discussion

This study reveals precise kinetics for the recognition between activated EGFR in its intact form embedded in the plasma membrane and an adaptor protein, Grb2, in solution. Single-molecule detection allowed us to measure individual on- and off-times for the reaction to clarify the complex behavior.

Dissociation between EGFR and Grb2 could be described by using multiple-exponential kinetics, with the major fraction (≈95%) showing a rate constant of 8 s−1. Rate constants for the minor components were ≈3 s−1 or lower. The kinetics of the association reaction was independent of the Grb2 concentration. EGFR has multiple tyrosine residues that are potentially phosphorylated after ligand binding. Phosphotyrosine (pY) 1068 and 1086 in EGFR have been reported to be the primary and secondary Grb2 binding sites, respectively (32). pY1068 is phosphorylated to a greater extent in vivo (33). The Y1068F mutant of EGFR (in which tyrosine 1068 is substituted by phenylalanine to prevent phosphorylation) was prepared (34) (R.I. and Eisuke Mekada, unpublished work), and we examined interactions with Grb2 in single molecules (SI Fig. 11 and SI Tables 4 and 5). Because the on-time distributions were similar to those of wild-type EGFR, the multiplicity in the dissociation was not caused by the difference between these two phosphotyrosine residues but by the overall protein structure.

Although rate constants for dissociation between intact molecules of EGFR and Grb2 have not been reported, complexes of Grb2 and Sos dissociate from a phosphopeptide of EGFR with a rate constant of 0.31 s−1 (16), which is lower than the major dissociation rate constant (8 s−1) obtained in this study by a factor of 26. This difference must be due to the intact molecules of EGFR used in this study, because complex formation with Sos increases the dissociation equilibrium constant between Grb2 and EGFR phosphopeptide by only a factor of 2.4 (16). This speculation is supported by the report that phosphorylation of Y1068 and Y1086 induces a conformational change in the EGFR C-terminal tail (19).

Association between EGFR and Grb2 required many reaction parameters to be described by using multiple-exponential kinetics. The distribution of the off-times for each concentration of Grb2 can be fitted with a sum of three exponential functions, but the association rates obtained varied, depending on the experimental conditions. In addition, ratios of the fractions of major (50–80%) and minor (20–50%) components were irregular and different from those observed in the dissociation kinetics, meaning that there was no 1:1 relationship between the association and dissociation states in multiple-exponential kinetics. When the association reaction was analyzed for individual binding sites, the rate constants were different for each site, and it was impossible to characterize the reactions at single binding sites by using a few common rate constants (SI Figs. 9 and 10). This result suggests the presence of many unbound substates, leading to the complexity observed in the multiple-exponential kinetic analysis.

Stretched exponential kinetics (35) provided a better representation of the association reaction with an exponent (α) of ≈0.5 for every concentration of Grb2 (Fig. 4). There are two typical cases for multiple-state reactions that can be described by using stretched exponential kinetics (24). In the first case, transition between multiple unbound substates takes place before the system reaches one target state for association. In the second case, there are many unbound states, each of which has a channel to the association state. In the former view, the value of α = 0.5 suggests a one-dimensional case of the defect-diffusion model (36). In this model, the binding events of Grb2 and EGFR can be recognized as the first-passage time problem of a one-dimensional random walk along substate variables to the target state. On the other hand, in single-spot analysis, one-third of the binding sites showed single-exponential behavior with different association rates for each spot, suggesting that the latter view is more suitable for the association between EGFR and Grb2. Other populations of the binding site showed multiple components in single-spot analysis, suggesting that transitions between different unbound substates took place during the observation. Therefore, it is probable that the reality is between these two extreme cases. More detailed information about the correlation between reaction and structural dynamics is required to reach a conclusion on this point.

The time constants (τ) for association in the stretched exponential kinetics were greater for the Y1068F mutant of EGFR (SI Fig. 11B). This result is consistent with the report that Y1068 is the major binding site of Grb2 (32). At 1 nM Grb2, histogram of the off-times was almost single exponential. However, at higher Grb2 concentrations, histograms were fitted by stretched exponential functions with α ∼ 0.5. Thus, multiplicity in association was preserved for the Y1068F mutant at least in the presence of 10 nM Grb2 or more.

The frequency of association events between wild-type EGFR and Grb2 was not proportional to the Grb2 concentration, in contrast to the usual case. Both the average off-time and τ decreased more slowly than the increase in Grb2 concentration. This result was not caused by direct competitive or noncompetitive inhibition between Grb2 molecules because simultaneous binding of multiple Cy3–Grb2 molecules at the same binding site was rarely observed, even at the highest concentration of Cy3–Grb2 (10 nM) used in this study. Even at 100 nM Grb2, the average off-time for Grb2 (2 s) expected from the off-times for Cy3–Grb2 was sufficiently longer than the average on-time (0.4 s) to avoid serious effects of simultaneous binding on the association rate. In addition, the effect of high concentrations of Grb2 was reversible (SI Fig. 8), suggesting that dynamic interactions between EGFR and Grb2 caused this phenomenon. The presence of multiple unbound states is highly likely to be responsible for the concentration dependence.

Conformational transition of the binding site can induce multiple reaction kinetics as shown in the allosteric model (37). One hypothesis is that Grb2 repeatedly interacts with EGFR for short times that were outside of our temporal resolution, accelerating substate transitions in the direction to increase the time constant of the association reaction. This effect seems to depend on specific interactions between EGFR and Grb2 but does not appear to be caused by nonspecific protein–protein interaction because the total protein concentration in the solution, which contained 0.5% casein and 1% BSA, was slightly affected by the different Grb2 concentrations in our experiments. Calculated from the theoretical maximum rate constant for association (38), assuming 2 nm for the interaction radius and 100 μm2·s−1 for the diffusion coefficient for the Grb2 molecule, at 10 nM Grb2, one binding site should collide with Grb2 molecules every 70 ms, whereas the average off-time was 9 s in this study. Such partial interactions possibly change the conformation of proteins and thus reduce the on-rates. To realize this mechanism, proteins would require a conformation memory after dissociation. When time constants for conformational transition of the binding site are comparable to that of association reaction, reaction memory can be induced due to dynamic disorder (20–23). In fact, the existence of reaction memory was suggested by non-Markovian function analysis of the single-molecule reaction trajectories (SI Fig. 12). A much lower reaction memory for the Y1068F mutant of EGFR at 1 nM Grb2 (SI Fig. 12C) supports this hypothesis; i.e., structural relaxation during long off-times would diminish conformational memories, and this could be a reason for the single-exponential kinetics under this condition (SI Fig. 11B).

Because of the Grb2 concentration dependence of the association kinetics, the dissociation equilibrium constant between EGFR and Grb2 changed according to the Grb2 concentration. As the concentration of Grb2 increased by a factor of 10, the affinity between EGFR and Grb2 decreased approximately by a factor of three. This relationship was maintained over a wide range (0.1–100 nM) of Grb2 concentrations. This phenomenon requires intact molecules of EGFR because it has not been observed in previous studies using short phosphopeptides from EGFR. The apparent dissociation constant was calculated from the total on- and off-times for each binding site. The average was 97, 340, and 650 nM at 1, 10, and 100 nM Grb2, respectively (Fig. 5). These values are similar to those reported in previous studies (100–710 nM) between phosphopeptides from EGFR and Grb2 (16–18). Concentration dependence was also observed for the Y1068F mutant (SI Fig. 13).

This concentration dependence can compensate for fluctuations in the expression level of Grb2 in living cells to maintain stable signal transduction from activated EGFR to Grb2. The concentration of Grb2 in the cytoplasm has not been quantified precisely yet, but in molecular network simulations of EGF signal transduction, the concentration of Grb2 was set between 3 nM (39) and 1 μM (40) to reproduce experimental results for the network response. Based on these results, the concentration of Grb2 in this study would not be very far from that in living cells. Therefore, it is highly probable that complex protein dynamics behavior is used to modulate intracellular signal transduction.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of the Plasma Membrane Fraction.

Human epithelial carcinoma A431 cells were grown on plastic dishes in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Nissui Pharmaceutical) supplemented with 10% FBS. The medium was changed before experiments to Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM) (Nissui Pharmaceutical) containing 1% BSA without phenol red and serum overnight. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng·ml−1 EGF for 5 min in MEM at room temperature to induce EGFR phosphorylation and then washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and the plasma membrane fraction was purified according to Yarden and Schlessinger (3). In brief, cells were treated with a hypotonic buffer and homogenized with a glass homogenizer, and the plasma membrane fraction was purified by using a sucrose density gradient. The buffer used for purification contained 1 mM sodium orthovanadate and 1 mM ATP to avoid dephosphorylation of EGFR, and a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma–Aldrich). For negative control of EGFR activation, cells were cultured overnight in the presence of 50 nM tyrphostin AG 1478 (Sigma–Aldrich), and the plasma membrane fraction was prepared in the presence of the same concentration of AG 1478. Tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR in the membrane fraction from EGF-stimulated cells was confirmed by immunoblotting (SI Fig. 6). The membrane fraction was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −85°C.

Preparation of Cy3-Labeled Grb2.

Preparation and Cy3 labeling of Grb2 were carried out as described by Ichinose et al. (41). Briefly, Grb2 was cloned from HeLa cells, expressed in E. coli, and purified. Monofunctional Cy3 (Amersham Pharmacia) was conjugated to the N terminus of Grb2. The reaction product was separated by using anion exchange column chromatography, and the fraction with a dye/protein ratio of 1 was collected as Cy3–Grb2. The 1:1 labeling was confirmed by single-step photobleaching under a total internal reflection fluorescence microscope (TIR-FM).

Observation.

To make an observation chamber, a coverslip (18 mm × 12 mm) was attached to a glass slide by using two strips of double-faced adhesive (200 μm thickness) as spacers, leaving two opposite sides open. The plasma membrane fraction was introduced into the chamber and kept on ice for 10 min. By this treatment, membrane fragments as small as the optical resolution (≈300 nm) were adsorbed on the coverslip. Then, as a maker to compensate for stage drift during observations, 10 pM Quantum Dot 565 (Quantum Dot Corporation) was introduced into the chamber and kept there for 5 min. After washing the unbound fraction with solution A [20 mM Hepes-KOH (pH 7.3), 110 mM CH3COOK, 5 mM CH3COONa, 2 mM (CH3COO)2Mg, 1 mM EGTA (pH 7.3), 1 mM DTT], the chamber was incubated with blocking solution (solution A containing 0.5% casein, 1% BSA, 0.5% polyethylene glycol). The solution was replaced with Cy3–Grb2 dissolved in blocking solution containing 4.5 mg·ml−1 glucose, 0.036 mg·ml−1 catalase, and 0.22 mg·ml−1 glucose oxidase, and the open sides of the chamber were closed with nail varnish. The concentration of Cy3–Grb2 was varied from 0.1 to 10 nM. Because single-molecule imaging was impossible in the presence of 100 nM Cy3–Grb2, 10 nM Cy3–Grb2 mixed with 90 nM nonlabeled Grb2 was used to analyze reactions at 100 nM Grb2.

The chamber was set on an objective type TIR-FM based on an inverted microscope (IX-70; Olympus) with an oil-immersion objective lens (Plan Apo ×60 N.A. 1.45). A diode-pumped solid-state laser (Millenia; Spectra Physics) with a 532-nm line was used to excite Cy3. Interactions between Cy3–Grb2 and EGFR were observed under the equilibrium condition. Because there were no cytosol and ATP, further phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of EGFR were avoided in the chamber. The image was captured for 18 min by using a monochrome CCD camera (CCD300-RC; Dage-MTI) after passing through an image intensifier (C8600; Hamamatsu Photonics). The image was averaged over two frames by using an image processor (ARGUS-20; Hamamatsu Photonics) and recorded in DVCAM format. The observations were carried out at 25°C. Photobleaching and blinking of Cy3–Grb2 were measured by fixing the molecules to the glass surface with anti-Grb2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Measurements of On- and Off-Times.

Changes in the fluorescence intensity at individual binding sites were measured from video movies by using image processing software (IPLab; Scanalytics). Stage drift was compensated for by using the movements of Quantum Dots (Qdot; Invitrogen) observed in the same field of view. The time points for association and dissociation of Cy3–Grb2 molecules were determined as follows. First, the average and standard deviation of the signal intensity were calculated during the association state (Avea and σa) and dissociation state (Aved and σd). Starting from a dissociation state, when the fluorescence intensity increased to more than Aved + 3σd for longer than two frames, this state was defined as association. On the contrary, when the fluorescence intensity of an association state decreased to less than Avea − 3σa for longer than two frames, this state was defined as dissociation. Each period of association or dissociation was measured as an on- or off-time, respectively.

Occasionally, Cy3–Grb2 came to the surface very close to the binding site of interest and affected the fluorescence intensity measurement. To exclude false binding caused by this effect, every frame for the binding duration was checked by eye. Binding sites in the stimulated membrane fraction to which Cy3–Grb2 bound with higher frequency than to those in the nonstimulated membrane fraction were used for analysis. The accumulated numbers of association or dissociation events were 1,400–5,200 from 29–38 binding sites for 1–100 nM Grb2. The numbers of association sites and events at 0.1 nM were 16 and 170, respectively.

Kinetic Analysis.

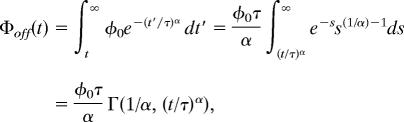

Reactions between EGFR and Grb2 were analyzed assuming multiple-exponential or stretched exponential kinetics. A stretched exponential function is described as

where φ(t) is the off-time, φ0 is a prefactor, α is the stretching exponent, and τ is the time constant. This function is a phenomenological fit that conveniently describes dynamics with broad time scales using only two parameters rather than multiple exponentials. In a wide range of disordered systems, including glasses and polymers, a stretched exponential relaxation phenomenon arises from contributions of a large number of weighted exponentials. In this study, we used cumulative histograms of on- and off-times to avoid the effect of bin-size on the kinetic parameters. The cumulative form of the stretched exponential function is

|

where s = (t/τ)α, and Γ(·,·) is the incomplete gamma function. This function can be calculated numerically, and the histograms were fitted to the functions by using the Levenberg–Marquardt method.

Because of the small number of association and dissociation events, the experimental results at 0.1 nM Cy3–Grb2 were not used for the multiple-exponential and stretched exponential analyses, but only the averages of on- and off-times were discussed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michio Hiroshima for technical assistance and Michiyuki Matsuda, Masahiro Ueda, and Eisuke Mekada for general support. H.T. is supported by the Leading Project (Bio Nano Process) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Abbreviation

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0701330104/DC1.

References

- 1.Carpenter G, Cohen S. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:193–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. Cell. 1990;61:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90801-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yarden Y, Schlessinger J. Biochemistry. 1987;26:1443–1451. doi: 10.1021/bi00379a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter G, King L, Jr, Cohen S. Nature. 1978;276:409–410. doi: 10.1038/276409a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen S, Carpenter G, King L., Jr J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4834–4842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowenstein EJ, Daly RJ, Batzer AG, Li W, Margolis B, Lammers R, Ullrich A, Skolnik EY, Bar-Sagi D, Schlessinger J. Cell. 1992;70:431–442. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90167-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rozakis-Adcock M, McGlade J, Mbamalu G, Pelicci G, Daly R, Li W, Batzer A, Thomas S, Brugge J, Pelicci PG, et al. Nature. 1992;360:689–692. doi: 10.1038/360689a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelicci G, Lanfrancone L, Grignani F, McGlade J, Cavallo F, Forni G, Nicoletti I, Pawson T, Pelicci PG. Cell. 1992;70:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90536-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahl MI, Nishibe S, Suh PG, Rhee SG, Carpenter G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1568–1572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meisenhelder J, Suh PG, Rhee SG, Hunter T. Cell. 1989;57:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chardin P, Camonis JH, Gale NW, van Aelst L, Schlessinger J, Wigler MH, Bar-Sagi D. Science. 1993;260:1338–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.8493579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozakis-Adcock M, Fernley R, Wade J, Pawson T, Bowtell D. Nature. 1993;363:83–85. doi: 10.1038/363083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li N, Batzer A, Daly R, Yajnik V, Skolnik E, Chardin P, Bar-Sagi D, Margolis B, Schlessinger J. Nature. 1993;363:85–88. doi: 10.1038/363085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gale NW, Kaplan S, Lowenstein EJ, Schlessinger J, Bar-Sagi D. Nature. 1993;363:88–92. doi: 10.1038/363088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egan SE, Giddings BW, Brooks MW, Buday L, Sizeland AM, Weinberg RA. Nature. 1993;363:45–51. doi: 10.1038/363045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chook YM, Gish GD, Kay CM, Pai EF, Pawson T. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30472–30478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemmon MA, Ladbury JE, Mandiyan V, Zhou M, Schlessinger J. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31653–31658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cussac D, Frech M, Chardin P. EMBO J. 1994;13:4011–4021. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishayee A, Beguinot L, Bishayee S. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:525–536. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.3.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu HP, Xun L, Xie XS. Science. 1998;282:1877–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Oijen AM, Blainey PC, Crampton DJ, Richardson CC, Ellenberger T, Xie XS. Science. 2003;301:1235–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.1084387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lerch HP, Rigler R, Mikhailov AS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10807–10812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504995102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan X, Nalbant P, Toutchikine A, Hu D, Vorpagel ER, Harn KM, Lu HP. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:737–744. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edman L, Rigler R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8266–8271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130589397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lerch HP, Mikhailov AS, Hess B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15410–15415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232376799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhuang X, Kim H, Pereira MJ, Babcock HP, Walter NG, Chu S. Science. 2002;296:1473–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.1069013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozuka J, Yokota H, Arai Y, Ishii Y, Yanagida T. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:83–86. doi: 10.1038/nchembio763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arai Y, Iwane AH, Wazawa T, Yokota H, Ishii Y, Kataoka T, Yanagida T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:809–815. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueda M, Sako Y, Tanaka T, Devreotes P, Yanagida T. Science. 2001;294:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1063951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hibino K, Watanabe TM, Kozuka J, Iwane AH, Okada T, Kataoka T, Yanagida T, Sako Y. ChemPhysChem. 2003;4:748–753. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200300731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teramura Y, Ichinose J, Takagi H, Nishida K, Yanagida T, Sako Y. EMBO J. 2006;25:4215–4222. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batzer AG, Rotin D, Urena JM, Skolnik EY, Schlessinger J. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5192–5201. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Downward J, Parker P, Waterfield MD. Nature. 1984;311:483–485. doi: 10.1038/311483a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwamoto R, Hanada K, Mekada E. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25906–25912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flomenbom O, Velonia K, Loos D, Masuo S, Cotlet M, Engelborghs Y, Hofkens J, Rowan AE, Nolte RJ, Van der Auweraer M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2368–2372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409039102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klafter J, Shlesinger MF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:848–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.4.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirshner K, Eigen M, Bitttman R, Voigt B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;56:1661–1667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.6.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berg OG, von Hippel PH. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1985;14:131–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.14.060185.001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maly IV, Wiley HS, Lauffenburger DA. Biophys J. 2004;86:10–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(04)74079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhalla US, Iyengar R. Science. 1999;283:381–387. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ichinose J, Morimatsu M, Yanagida T, Sako Y. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3343–3350. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.