Abstract

β-arrestins (β-arrs), two ubiquitous proteins involved in serpentine heptahelical receptor regulation and signaling, form constitutive homo- and heterooligomers stabilized by inositol 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexakisphosphate (IP6). Monomeric β-arrs are believed to interact with receptors after agonist activation, and therefore, β-arr oligomers have been proposed to represent a resting biologically inactive state. In contrast to this, we report here that the interaction with and subsequent titration out of the nucleus of the protooncogene Mdm2 specifically require β-arr2 oligomers together with the previously characterized nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of β-arr2. Mutation of the IP6-binding sites impair oligomerization, reduce interaction with Mdm2, and inhibit p53-dependent antiproliferative effects of β-arr2, whereas the competence for receptor regulation and signaling is maintained. These observations suggest that the intracellular concentration of β-arr2 oligomers might control cell survival and proliferation.

Keywords: bioluminescence resonance energy transfer, FRET, nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, ubiquitination

β-arrestin-1 (β-arr1, also known as arrestin 2) and β-arr2 (or arrestin 3) are two ubiquitously expressed multifunctional proteins, which bind to ligand-activated phosphorylated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Originally identified as negative regulators of GPCR function, because their binding promotes GPCR desensitization (1), they were subsequently shown to play a role as adaptor proteins connecting GPCRs to the endocytic machinery (2–4). It is now increasingly apparent that, in addition to their regulatory functions, β-arrs may also represent signaling adaptors connecting GPCRs, as well as receptors of other families, to a growing number of effector pathways (reviewed in refs. 5–8). Although most functions of β-arrs depend on their interactions with molecular partners at the plasma or endosomal membranes, β-arrs also have biological roles within the nucleus. For example, β-arr2 (not β-arr1) redistributes the prooncogenic ubiquitin ligase Mdm2 (9) and the JNK3 kinase (10) from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. This property depends on the presence of a leucine-rich nuclear export signal in the C terminus of β-arr2, which mediates the nuclear export of β-arr2 by leptomycin B-sensitive exportins (11). More recently, it has been reported that, despite the fact that β-arr1 does not shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm like β-arr2, it can accumulate in the nucleus in response to receptor activation and interact with specific promoters. Such an accumulation facilitates the recruitment of a histone acetyltransferase, enhancing local histone acetylation and gene transcription (12).

Early structural studies conducted on β-arr1 and arrestin, found exclusively in visual tissues, reported the existence of oligomers in crystals, indicating that this family of proteins may have the propensity to form oligomers (13–15). However, the existence of constitutive oligomers in living cells at physiological concentrations was only recently confirmed (16). The oligomeric state of β-arrs appears to be stabilized by IP6 (17). This sugar bridges two binding sites located, respectively, on the N- and C-terminal globular domains of two different β-arr protomers. It is noteworthy that the IP6-binding site on the C-terminal domain and the residues implicated in attachment to plasma membrane phosphoinositides, upon β-arr translocation to activated receptors (18), are partially overlapping. Mutation of either IP6-binding site of β-arr1 impaired β-arr1 oligomerization, whereas interactions of IP6-binding mutants with known binding partners, such as clathrin, AP-2, and ERK2 were maintained (17). Based on the above findings, it was proposed that IP6 binding would be a negative regulator of β-arr interactions with plasma membrane partners by promoting cytosolic oligomerization, and that, consequently, β-arrs would interact with GPCRs as monomers. Oligomers would thus represent an inactive pool of β-arrs stocked in the cytoplasm.

The fact that β-arr functions at the plasma membrane likely involve monomeric forms does not exclude specific roles for β-arr oligomers in other subcellular compartments. In particular, delocalization of nuclear proteins, such as Mdm2, via the permanent nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of β-arr2, may occur even in the absence of receptor activation (9, 11) and might thus involve β-arr2 oligomers. This hypothesis was investigated here. Based on the structural information available for the β-arr1 dimer (17), mutations predicted to affect IP6 binding and stability of β-arr2 oligomers were generated and their influence on function assessed. Impairment of β-arr2 oligomerization selectively inhibited β-arr2–Mdm2 interaction as well as p53-dependent antiproliferative effects of WT β-arr2 in tumor cells. These findings are consistent with a previously uncharacterized specific function of β-arr2 oligomers in the physiopathological control of cell division.

Results

Characterization of β-arr2 IP6-Binding Mutants.

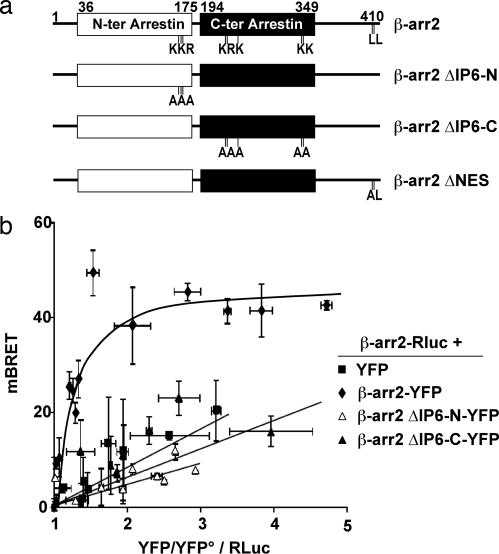

The Lys and Arg residues forming the IP6-binding site, which are located in either the N- or C-terminal globular domains of β-arr1 (17), are conserved in the β-arr2 sequence. Alanine substitutions of corresponding residues were performed in the rat β-arr2 cDNA, resulting in either the N-terminal domain mutant (K158A, K161A, and R162A), referred to as β-arr2ΔIP6-N, or the C-terminal domain mutant (K232A, R234A, K252A, K326A, and K328A), referred to as β-arr2ΔIP6-C (Fig. 1a). Coimmunoprecipitation experiments in COS7 cells with β-arr2ΔIP6-N and β-arr2ΔIP6-C showed that the mutation of the IP6-binding sites in either domain of β-arr2 is sufficient to inhibit oligomerization compared with WT β-arr2 [supporting information (SI Fig. 5). The impairment of β-arr2 self-association was confirmed in living HEK293 cells by using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assays (16), conducted with WT and mutant forms of β-arr2 fused to either Renilla luciferase (Rluc), the BRET donor, or the yellow variant of EGFP (YFP), the BRET acceptor (Fig. 1b). In BRET saturation experiments with WT β-arr2 fusion proteins, a hyperbolic curve was obtained, demonstrating the progressive saturation of the BRET donor with increasing concentrations of the acceptor, which is representative of oligomer formation. In control experiments, using free YFP as BRET acceptor, weaker BRET signals were observed, linearly increasing with the acceptor concentration, corresponding to nonspecific bystander BRET. Interestingly, similar nonspecific signals were observed with β-arr2ΔIP6-N and β-arr2ΔIP6-C, confirming their lower propensity to self-associate in vivo.

Fig. 1.

β-arr2 IP6-binding site mutants show impaired oligomerization. (a) β-arr2 constructs used in the study. Boxes indicate N- and C-terminal globular domains of β-arr2 (N-ter arrestin and C-ter arrestin, respectively). Positions of alanine substitutions to generate the mutants of the N-terminal and C-terminal IP6-binding sites (ΔIP6-N and ΔIP6-C, respectively) and of the NES of β-arr2 (ΔNES) are shown. (b) BRET saturation curves obtained by measuring BRET ratios in HEK293T cells expressing fixed quantities of BRET donor (β-arr2-Rluc) and increasing amounts of BRET acceptors (YFP-tagged β-arr2 constructs and control YFP). Relative amounts of BRET acceptor are expressed as the ratio between the fluorescence of the acceptor over the luciferase activity of the donor. YFP° corresponds to background fluorescence in cells expressing the BRET donor alone. Error bars indicate SD of mean specific BRET-ratio values from 21 to 42 individual transfections grouped as a function of the amount of BRET acceptor.

Assays were next conducted to examine whether the mutation of IP6-binding sites would perturb important biological functions of β-arr2. The predominantly cytoplasmic distribution of β-arr2 at steady-state was not affected by mutations (SI Fig. 6a). Upon Angiotensin II receptor activation, β-arr2 mutants were recruited normally in clathrin-coated pits and then accumulated in endosomes (SI Fig. 6 b and c), the kinetic of agonist-promoted GPCR internalization being comparable in cells expressing WT β-arr2 and mutants (SI Fig. 6d). Both IP6-binding mutants retained the capacity to interact with known β-arr2 partners such as the AP2 adaptor (4) or Filamin A (19) in coimmunoprecipitation experiments (SI Fig. 7). Finally, the MAP kinase scaffolding properties of β-arr2ΔIP6-N and β-arr2ΔIP6-C were not impaired, as shown by the preserved agonist-induced β-arr-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (SI Fig. 8), in agreement with previous results showing that β-arr1 IP6-binding mutants still interact with ERK2 (17).

Mutation of the conserved basic residue patches forming the IP6 contact sites of β-arr1 was reported to prevent the formation of oligomers and to increase its nuclear localization (17). This observation was interpreted as an indication that monomers have a more efficient nuclear import mechanism than oligomeric β-arr1. Because β-arr2 permanently shuttles between the cytosol and the nucleus, because of its nuclear import and export signals, we examined whether mutations of the IP6-binding sites would perturb this property. Incubation of HeLa cells expressing either WT or mutant β-arr2 with leptomycin B (LMB), an inhibitor of the CRM1 exportin, induced comparable extent and kinetics of nuclear accumulation (SI Fig. 9 a and b). These observations indicate that, at least for β-arr2, oligomerization does not affect nuclear import. The nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of β-arr2 was reported to redistribute the JNK3 MAP kinase from the nucleus to the cytosol (11). β-arr2, β-arr2ΔIP6-N, and β-arr2ΔIP6-C showed a comparable effect on JNK3 redistribution from the nucleus to the cytosol (SI Fig. 9 c and d).

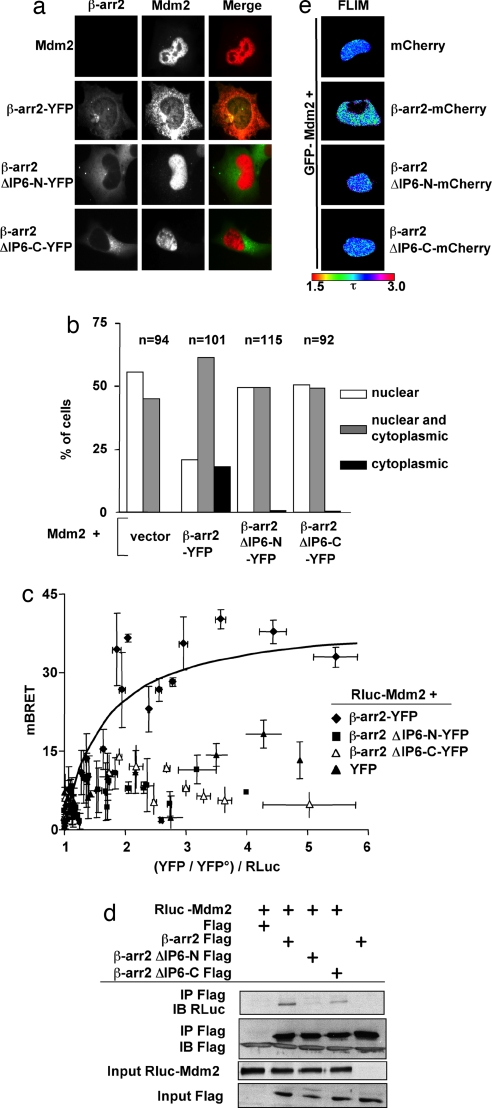

Impaired Interaction of β-arr2 IP6-Binding Mutants with Mdm2.

The protooncogene Mdm2 is another interaction partner, which can be titrated out of the nucleus via the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of β-arr2 (9). We therefore investigated the capacity of β-arr2-YFP to redistribute coexpressed Mdm2 (Fig. 2 a and b). In control experiments, Mdm2 appeared exclusively nuclear in >50% of HeLa cells and was never found to be exclusively cytosolic. In cells coexpressing β-arr2-YFP, Mdm2 was exclusively nuclear in only ≈20% of the cells and appeared to be exclusively cytosolic in approximately the same proportion. In contrast, the two mutants of IP6-binding sites failed to redistribute Mdm2 to the cytosol. We examined whether the observed phenotype could be related to the impaired capacity of β-arr2ΔIP6-N and β-arr2ΔIP6-C to interact with Mdm2. In saturation BRET experiments conducted with Rluc-Mdm2 as donor, a specific saturable BRET signal could be obtained only with β-arr2-YFP (Fig. 2c). Experiments with both β-arr2ΔIP6-N-YFP and β-arr2ΔIP6-C-YFP only provided nonspecific signals comparable with those obtained with free YFP. Importantly, specific BRET signals were obtained for concentrations of exogenous WT and mutant β-arr2, which are comparable with that of endogenous β-arr2 in primary human cells (SI Fig. 10). The assumption that impaired oligomerization of β-arr2 would affect the stability of its interaction with Mdm2 was corroborated by coimmunoprecipitation experiments, which showed that β-arr2ΔIP6-N and β-arr2ΔIP6-C (to a lesser extent) were less effective than WT β-arr2 to coimmunoprecipitate Mdm2 (Fig. 2d). To directly visualize the β-arr2-Mdm2 interaction in live cells, we used fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), a well adapted method to measure FRET in living cells (16). In these experiments, Mdm2 was fused to EGFP (the FRET donor) and WT or mutant β-arr2 to the red fluorescent protein mCherry (the FRET acceptor) (20). The fluorescence decay of EGFP, measured at steady-state in cells where EGFP-Mdm2 was redistributed to the cytosol by β-arr2-mCherry, was significantly reduced compared with cells expressing the FRET donor and control mCherry. This result is indicative of energy transfer and thus of the existence of Mdm2-β-arr2 interaction (Fig. 2e). In control cells expressing β-arr2ΔIP6-N-mCherry or β-arr2ΔIP6-C-mCherry, no FRET was observed, consistent with their absence of interaction with Mdm2 and with their failure of redistributing EGFP-Mdm2 out of the nucleus.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of β-arr2 oligomerization impairs cytosolic delocalization of Mdm2. (a) HeLa cells expressing β-arr2-YFP, β-arr2ΔIP6-N-YFP, or β-arr2ΔIP6-C-YFP constructs and Mdm2. Anti-Mdm2 monoclonal antibody was revealed by using a secondary Cy3-labeled donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody. Similar results were obtained in H1299, COS, and HEK293T cells (data not shown). (b) Determination of predominant nuclear, cytosolic, or diffuse Mdm2 localization in the indicated number of cells used in immunofluorescence experiments. Bars indicate the percentage of cells in each category. Similar results were obtained in H1299 cells (data not shown). (c) BRET saturation experiments (as described in Fig. 1b) in HEK293T cells expressing Rluc-Mdm2 as BRET donor and the indicated acceptors (individual transfections, n = 33–66). (d) Interaction between Mdm2 and β-arr2 assessed by coimmunoprecipitation experiments. COS7 cells were cotransfected with (1 μg) of β-arr2, β-arr2ΔIP6-N, or β-arr2ΔIP6-C Flag-tagged constructs or control empty vector and Rluc-Mdm2 cDNA. After immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibodies, immunoblots were probed with anti-RLuc antibodies; 10% of input is shown. (e) FLIM in unstimulated HEK293 live cells expressing EGFP-Mdm2 (the FRET donor), alone or in association with the indicated FRET acceptors: mCherry, β-arr2-mCherry, β-arr2 ΔIP6-N-mCherry, and β-arr2 ΔIP6-C-mCherry. Average values (±SEM, n = 10) of fluorescence lifetime (τ), shown in the figure with a pseudocolor scale (from 1.5 to 3 ns) were 2.386 + 0.004, 2.259 ± 0.014, 2.386 ± 0.005, and 2.405 ± 0.012, respectively. Only β-arr2-mCherry significantly decreased the fluorescence lifetime of GFP-Mdm2 (P < 0.05).

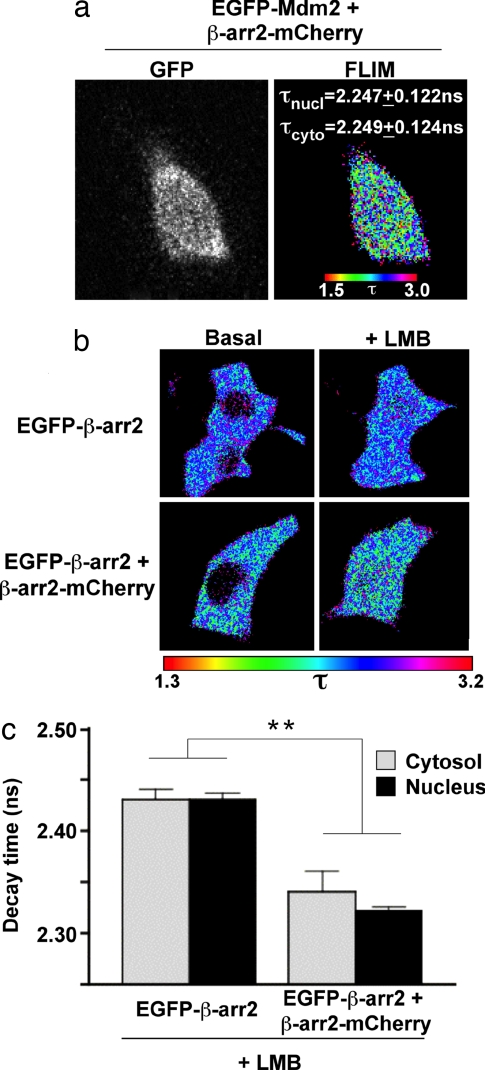

The data above also support the hypothesis that β-arr2 oligomers are able to interact with Mdm2 in the nucleus. The existence of β-arr2-Mdm2 complexes within the nucleus could indeed be visualized by FLIM (Fig. 3a). Moreover, nuclear β-arr2 oligomers were directly visualized by the same approach using EGFP-β-arr2 as FRET donor (Fig. 3b). In the presence of LMB, β-arr2 oligomers progressively accumulated in the nuclear area, and no significant difference of fluorescence decay could be measured between the nucleus and the cytosol, demonstrating similar levels of oligomerization in the two compartments (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Visualization of β-arr2–Mdm2 interaction and of β-arr2 oligomers in the nucleus. (a) Nuclear and cytosolic FRET between EGFP-Mdm2 (FRET donor) and mCherry-tagged β-arr2 constructs (FRET acceptors) expressed in live HEK293 cells. Fluorescence lifetime (τ) of FRET donor in both nuclear (τnucl) and cytosolic (τcyto) areas of cells displaying diffuse distribution of both Mdm2 and WT β-arr2 (gray columns in Fig. 2b) is indicated. Values measured in the nuclear area in the presence of mCherry, β-arr2 ΔIP6-N-mCherry and β-arr2 ΔIP6-C-mCherry were, respectively, 2.386 ± 0.106, 2.378 ± 0.182, and 2.406 ± 0.138 (mean ± SD); they were significantly higher (P < 0.001) than that measured with β-arr2-mCherry. (b) FLIM in unstimulated HEK293 live cells expressing EGFP-β-arr2 (FRET donor), alone or in association with β-arr2-mCherry (FRET acceptor), under basal condition or in the presence of 20 nM LMB. Fluorescence lifetime is shown by using a pseudocolor scale. (c) Comparison of fluorescence lifetime values after LMB treatment in cells expressing the FRET donor alone or both FRET donor and acceptor. **, significant difference between τ values were observed in both nucleus and cytosol (P < 0.001).

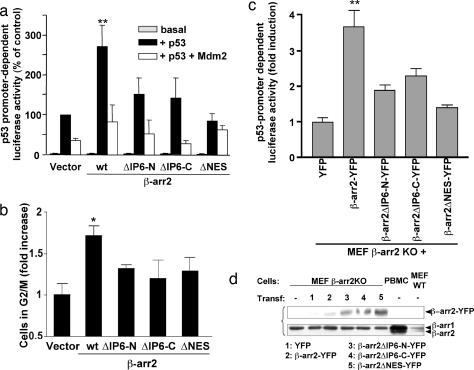

A major biological function of Mdm2 is to control the stability of the p53 protein and, consequently, to counteract p53 effects on cell survival and proliferation (21). Because it was reported that binding of β-arr2 reduces Mdm2-mediated p53 degradation and thus enhances p53 activity (22), we investigated whether these effects would be lost because of the impaired interaction of both β-arr2ΔIP6 mutants with Mdm2. Transcriptional effects of p53 involve interaction with specific binding motifs in the promoter of p53-regulated genes (23). The p53 negative H1299 human lung carcinoma cells were cotransfected with various β-arr2 constructs and a plasmid coding for luciferase under the control of a p53-regulated promoter, in the presence or absence of exogenous p53 and/or Mdm2 (Fig. 4a). In this system, the expression of exogenous p53 alone markedly enhanced the luciferase signal. The coexpression of β-arr2 induced a specific additional increase of the signal. The functional link between this effect and the Mdm2-dependent regulation of p53 was confirmed by the fact that the β-arr2-promoted enhancement was inhibited in case of exogenous Mdm2 overexpression. Interestingly, neither IP6-binding mutants or the NES-deleted mutant (β-arr2 ΔNES, Fig. 1a), which cannot redistribute Mdm2 to the cytosol because of its inhibited nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (9), could significantly increase p53-dependent luciferase activity. One of the first consequences of p53 expression in nearly all mammalian cell types is a block in the cell-division cycle either at the G1-to-S or at the G2-to-mitosis transition (24). The reintroduction of p53 in H1299 cells increased the number of cells arrested in the G2/M phase (Fig. 4b). Cotransfection of β-arr2 significantly enhanced the G2 block, whereas coexpression of β-arr2ΔIP6-N, β-arr2ΔIP6-C, or β-arr2 ΔNES was ineffective.

Fig. 4.

β-arr2-dependent enhancement of p53 activity requires oligomerization and nuclear shuttling of β-arr2. (a) H1299 cells growing in six-well plates were cotransfected with the p53-cis reporter-Luc (200 ng; Stratagene) and/or cDNA coding for p53 with or without Mdm2 cDNA (0.5 μg each) and the indicated β-arr2 YFP-tagged constructs (0.5 μg). Total transfected DNA was kept constant by using an empty vector. p53 promoter-dependent transcription (the luciferase signal) and β-arr-associated fluorescence (for normalization) were measured; (**, P < 0.001, β-arr2 vs. vector in cells expressing p53 alone). (b) H1299 cells were transfected with equivalent amounts of cDNAs coding for p53, the indicated β-arr2 YFP-tagged constructs or empty vector. At 48 h after transfection, nuclei were stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml), and cell cycle phases were analyzed by FACS. Data indicate the fold increase of cells expressing YFP constructs in G2–M phase, comparatively with cells transfected with vector DNA; *, P < 0.05 WT β-arr2 vs. vector. Cell distribution in the various phases of cell cycle is shown in SI Table 1. (c) MEF β-arr2KO were transfected with p53-Luc reporter and reconstituted with the indicated β-arr2 YFP-tagged constructs (1 μg per 35-mm dish). p53 promoter-dependent transcription and β-arr-associated fluorescence were measured as in a; (**, P < 0,001). (d) Immunoblot analysis of WT and mutant β-arr2 in reconstituted MEF β-arr2KO, comparatively with WT MEF and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), as described in SI Fig. 6.

The experiments above were conducted in cells overexpressing exogenous β-arr2 in addition to the endogenous β-arr2 found in H1299. To make sure that the functional effects on p53 function were not biased by overexpression, we took advantage of mouse embryonic fibroblasts obtained from β-arr2 knockout embryos (MEF β-arr2KO) (25). MEF β-arr2KO cells were reconstituted with “physiological” concentrations of WT or mutant β-arr2, and the functional effects of reconstitution on p53 transcriptional activity were analyzed (Fig. 4 c and d). The results obtained reproduced those obtained with H1299 cells, indicating that effects on p53 activity can indeed be regulated by endogenous levels of β-arr2.

Taken together, these results indicate that β-arr2 promotes p53 function and that, in addition to the interaction with Mdm2, this biological function requires both preserved nucleocytoplasmic shuttling, and self-assembly of β-arr2.

Discussion

Although the existence of homo- and heterooligomers of β-arrs has been documented with multiple experimental approaches, the attribution of important biological function to β-arr2 oligomers has not been previously made. Indeed, we have shown that the β-arr2-dependent titration of the oncoprotein Mdm2 out of the nucleus and the subsequent enhancement of p53 activity, were inhibited when self-assembly of β-arr2 was prevented by mutation of the binding sites for IP6, a sugar reported to stabilize the association between the N-terminal and C-terminal globular domains of two β-arr2 protomers. These mutations did not affect the overall capacity of β-arr2 to shuttle between the cytosol and the nucleus, and their effect was specific for Mdm2 because JNK3, another nuclear protein interacting with β-arr2, was normally redistributed into the cytosol in the presence of β-arr2 IP6-binding mutants.

The interface between β-arr2 and Mdm2 was mapped by coimmunoprecipitation experiments (22) and two-hybrid studies (unpublished results) to the N-terminal domain of β-arr2, between positions 154 and 180. Thus, it is possible that mutations of the IP6-binding sites not only destabilize the β-arr2 oligomer but might also directly inhibit the interaction with Mdm2, consistent with the complete inhibition of the coimmunoprecipitation of the β-arr2ΔIP6-N. A similar direct effect on Mdm2 binding, however, cannot be attributed to mutations of the C-terminal IP6-binding site (K232A, R234A, K252A, K326A, and K328A), which still caused comparable effects in terms of Mdm2 redistribution as mutations of the N-terminal domain. Mdm2 is a RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligase, which was reported to dimerize in vitro (26). The solution structure of the RING domain of the human homolog of Mdm2 revealed a symmetrical dimer (27), and it was proposed that Mdm2 homodimers rather than monomers display the E3 ubiquitin-ligase activity (28). Thus the availability of multiple binding sites within a β-arr2 oligomer might increase the affinity for Mdm2 dimers and stabilize the complex.

Ubiquitination of β-arr2, catalyzed by the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of Mdm2, was reported to be essential for mediating GPCR endocytosis (29, 30), whereas in our experiments endocytosis of the TRH receptor was not affected by mutations inhibiting the stable interaction of β-arr2 with Mdm2 and which might thus prevent its ubiquitination. We verified that GPCR-stimulated ubiquitination of β-arr2ΔIP6-N and β-arr2ΔIP6-C was maintained (data not shown), indicating that the stable association with Mdm2 is not obligatory for β-arr2 ubiquitination. It was reported recently that Mdm2 and the receptor kinase GRK2 interact in resting cells and that their association is enhanced by GPCR activation and β-arr overexpression (31), suggesting that stimulated receptors may promote the formation of complexes comprising β-arr, Mdm2, and GRK2. In line with these findings, GRK2-Mdm2 complexes and β-arr2 IP6-binding mutants might be independently translocated to activated receptors. Once in close proximity, β-arr2ΔIP6-N and β-arr2ΔIP6-C might become substrate of Mdm2 in the absence of any previous stable interaction and, thus, remain competent for mediating normal receptor endocytosis. Alternatively, another E3 ligase might be able to substitute for Mdm2 in our experimental conditions.

Using FLIM, we could directly visualize the presence of β-arr2 oligomers in the nucleus, at the same concentration as in the cytosol, after inhibiting CRM1-dependent nuclear export with LMB. Oligomers accumulated in the nucleus with the same kinetics as total β-arr2. Because the redistribution of Mdm2 to the cytosol by β-arr2 also requires an intact NES, these findings support a model where the interaction between Mdm2 and β-arr2 oligomers occurs in the nucleus, the complex being subsequently exported to the cytosol via the interaction with the CRM1 exportin. Consistent with this hypothesis is the direct visualization of β-arr2–Mdm2 interaction in the nucleus by FLIM.

By regulating the subcellular localization of Mdm2, β-arr2 oligomers indirectly modulate the function of p53. This protein is a transcription factor, which has been implicated as a major mediator of cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis in the response of mammalian cells to stress stimuli (32). In addition, loss or mutation of p53 is strongly associated with an increased susceptibility to cancer. Inhibiting oligomerization or nuclear export reduced the enhancing effect of β-arr2 on the p53 transcriptional effect in vitro and on the p53-dependent cell-cycle arrest in G2/M. This is not the first example of cell growth modulation via β-arr2. Indeed, it was reported recently that β-arr2 stimulates the transcriptional activation of retinoid RAR receptors and that the inhibition of PC12 cell growth in response to nerve growth factor involves the β-arr2- and ERK2-dependent transcriptional activation of the RAR-β2 receptor (33). Together with our data, these observations suggest a possible previously unappreciated role of β-arrs in the control of cell division with multiple points of impact. Future studies will be necessary to determine whether tissue concentration of β-arr oligomers may regulate mitogenic responses in normal and cancer tissues and how this effect might be regulated by external stimuli.

Methods

Reagents and Cells.

Unless otherwise specified, all products were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). WT and β-arr2KO MEF as well as the anti β-arr polyclonal A1CT antibody were a kind gift of Robert Lefkowitz (Duke University, Durham, NC). Complete protease inhibitor mixture and the 9E10 anti-Myc were from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). The anti-Mdm2 antibody was homemade (R.F. laboratory), anti-Rluc antibody was from Chemicon (Billerica, MA), anti-AP2 antibody (M300) and A/G Sepharose were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated polyclonal donkey anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG and secondary antibodies for fluorescence microscopy were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA).

GeneJuice transfection reagent was from Novagen (Darmstadt, Germany), Lipofectamine 2000 was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The cDNA of human Mdm2 was kindly provided by N. Varin-Blank (Institut Cochin), and the p53 plasmid was described previously (34). Various tagged forms of β-arr2 have been described previously (16).

HeLa, COS7, HEK-293T, and H1299 cell lines were from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Culture media were from Invitrogen. The p53-deficient H1299 cells were maintained in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. For the other cells, Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium was used instead of the RPMI.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis.

Plasmids coding for β-arr2 ΔIP6-N and β-arr2 ΔIP6-C were prepared by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and following the instructions of the manufacturer.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting.

Approximately 3 × 106 cells growing in 100-mm dishes were transfected with 1 μg of each plasmid as indicated in figure legends. At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed in cold glycerol lysis buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5)/150 mM NaCl/2 mM EDTA/1% Triton/100 μM Na3VO4/1 mM NaF/10% (vol/vol) glycerol] in the presence of protease inhibitors. Immunoprecipitations were performed on 500 μg of cell lysates by using the monoclonal M2 anti-FLAG-affinity agarose or 9E10 anti-Myc antibody coupled to protein A/G Sepharose. After incubation, coimmunoprecipitated proteins and inputs were analyzed by Western blot.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells, transfected with 0.2 μg of pCDNA-Mdm2 and 1 μg of a β-arr2-EGFP construct, were fixed and processed for fluorescence microscopy as described (35). Samples were examined under an epifluorescence DMIRB inverted microscope (Leica, St. Gallen, Switzerland) attached to a cooled CCD camera (MicroMAX-1300Y/HS; Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ).

BRET Saturation Assays.

HEK293T cells were transfected with 0.1 μg per well of the DNA construct coding for BRET donor and increasing (0.1–1 μg per well) amounts of the BRET acceptor plasmid (or control YFP). At 24 h after transfection, the luciferase substrate, coelenterazine h (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands), was added at a final concentration of 5 μM to 1 × 105 cells. Luminescence and fluorescence were measured simultaneously by using the Mithras fluorescence-luminescence detector (Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Cells expressing BRET donors alone were used to determine background. Filter sets were 485 ± 10 nm for luciferase emission and 530 ± 12.5 nm for YFP emission. BRET ratios were calculated as described (16).

p53 Promoter Luciferase Assay.

H1299 cells were cotransfected with pRLTK (Promega, Madison, WI), plasmids expressing the indicated forms of β-arr2, and the p53-cis reporter-Luc (Stratagene). Total transfected DNA was maintained constant by using appropriate amounts of pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). After 48 h, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured by using the Dual Luciferase Assay kit (Promega) in a luminometer (Berthold Instruments) according to manufacturer's protocol.

Flow Cytometry.

At 48 h after transfection, H1299 cells were harvested and fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol. After 30 min incubation with RNase at 37°C, cells were stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) and analyzed with a LSR flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

FLIM.

FLIM experiments were performed as described (16), with the technical modifications reported in (20). The detailed procedure can be found in SI Methods.

Statistical Analysis.

Data are expressed as a mean value ± SD or SEM. All results were confirmed in at least three separate experiments. Data were analyzed by using Student's t test and P < 0.05 (at least) was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jean Liotard for skilled technical assistance and Albane Bizet (Institut Cochin) for RLuc-Mdm2. This work was supported by grants from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Université Paris Descartes, the Ligue Contre le Cancer Comité de l'Oise, the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC 36-91), and the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

Abbreviations

- β-arr

β-arrestin

- BRET

bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- IP6

inositol 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexakisphosphate

- LMB

leptomycin B

- NES

nuclear export signal.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0705550104/DC1.

References

- 1.Lohse MJ, Benovic JL, Codina J, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Science. 1990;248:1547–1550. doi: 10.1126/science.2163110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson SS, Downey WE, Colapietro AM, Barak LS, Menard L, Caron MG. Science. 1996;271:363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodman OBJ, Krupnick JG, Santini F, Gurevich VV, Penn RB, Gagnon AW, Keen JH, Benovic JL. Nature. 1996;383:447–450. doi: 10.1038/383447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laporte SA, Oakley RH, Zhang J, Holt JA, Ferguson SS, Caron MG, Barak LS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3712–3717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:cm10. doi: 10.1126/stke.2005/308/cm10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiter E, Lefkowitz RJ. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchanan FG, DuBois RN. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2060–2063. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.18.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefkowitz RJ, Rajagopal K, Whalen EJ. Mol Cell. 2006;24:643–652. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P, Wu Y, Ge X, Ma L, Pei G. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11648–11653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald PH, Chow CW, Miller WE, Laporte SA, Field ME, Lin FT, Davis RJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Science. 2000;290:1574–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott MG, Le Rouzic E, Perianin A, Pierotti V, Enslen H, Benichou S, Marullo S, Benmerah A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37693–37701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang J, Shi Y, Xiang B, Qu B, Su W, Zhu M, Zhang M, Bao G, Wang F, Zhang X, et al. Cell. 2005;123:833–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granzin J, Wilden U, Choe HW, Labahn J, Krafft B, Buldt G. Nature. 1998;391:918–921. doi: 10.1038/36147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch JA, Schubert C, Gurevich VV, Sigler PB. Cell. 1999;97:257–269. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han M, Gurevich VV, Vishnivetskiy SA, Sigler PB, Schubert C. Structure (London) 2001;9:869–880. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00644-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Storez H, Scott MG, Issafras H, Burtey A, Benmerah A, Muntaner O, Piolot T, Tramier M, Coppey-Moisan M, Bouvier M, et al. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40210–40215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milano SK, Kim YM, Stefano FP, Benovic JL, Brenner C. J Biol Chem. 2006;81:9812–9823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaidarov I, Krupnick JG, Falck JR, Benovic JL, Keen JH. EMBO J. 1999;18:871–881. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott MG, Pierotti V, Storez H, Linberg E, Thuret A, Muntaner O, Labbé-Jullié C, Pitcher JA, Marullo S. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3432–3445. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3432-3445.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tramier M, Zahid M, Mevel JC, Masse MJ, Coppey-Moisan M. Microsc Res Tech. 2006;69:933–939. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubbutat MH, Jones SN, Vousden KH. Nature. 1997;387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang P, Gao H, Ni Y, Wang B, Wu Y, Ji L, Qin L, Ma L, Pei G. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6363–6370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210350200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Deiry WS. Semin Cancer Biol. 1998;8:345–357. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohout TA, Lin FS, Perry SJ, Conner DA, Lefkowitz RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1601–1606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041608198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linares LK, Scheffner M. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kostic M, Matt T, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. J Mol Biol. 2006;363:433–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh RK, Iyappan S, Scheffner M. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10901–10907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shenoy SK, McDonald PH, Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Science. 2001;294:1307–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.1063866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14498–14506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salcedo A, Mayor F, Jr, Penela P. EMBO J. 2006;25:4752–4762. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Voudsen KH, Lane DP. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:275–283. doi: 10.1038/nrm2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piu F, Gauthier NK, Wang F. Oncogene. 2006;25:218–229. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Candeias MM, Powell DJ, Roubalova E, Apcher S, Bourougaa K, Vojtesek B, Bruzzoni-Giovanelli H, Fahraeus R. Oncogene. 2006;25:6936–6947. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott MG, Benmerah A, Muntaner O, Marullo S. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3552–3559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.