Abstract

The arachidonic acid (AA) cascade involves the release of AA from the membrane phospholipids by a phospholipase A2 (PLA2), followed by its subsequent metabolism to bioactive prostanoids by cyclooxygenases (COX) coupled with terminal synthases. Altered brain AA metabolism has been implicated in neurological, neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. The development of genetically altered mice lacking specific enzymes of the AA cascade has helped to elucidate the individual roles of these enzymes in brain physiology and pathology. The roles of AA and its metabolites in brain physiology, with a particular emphasis on the PLA2 /COX pathway, are summarized, and the specific phenotypes of genetically altered mice relevant to brain physiology and neurotoxic models are discussed.

Keywords: cyclooxygenase, phospholipase A2, prostaglandin, knockout, neurotoxicity, genetic models

Background

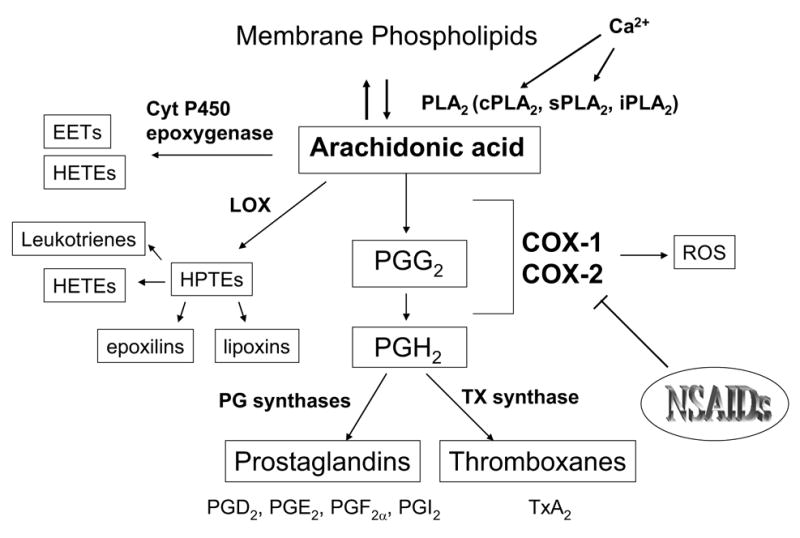

The arachidonic acid (AA) cascade (Figure 1) is the biosynthetic pathway which involves the release of the n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid AA from the sn-2 position of membrane phospholipids by a phosholipase A2 (PLA2) enzyme, and its subsequent metabolism to bioactive prostaglandins (PGs), thromboxanes, leukotrienes and epoxy fatty acids, by cyclooxygenase (COX), lipoxygenase (LOX) and cytochrome P450 epoxygenase enzymes, coupled to specific terminal synthases (Fitzpatrick and Soberman 2001). AA and its end-products are involved in physiological processes in the central nervous system such as synaptic signaling (Kaufmann et al. 1996), neuronal firing (Chapman and Dickenson 1992), neurotransmitter release (Ojeda et al. 1989), nociception (Hori et al. 1998), neuronal gene expression (Lerea and McNamara 1993; Lerea et al. 1997), cerebral blood flow (Pickard 1981; Li et al. 1997; Stefanovic et al. 2006), sleep/wake cycle (Hayaishi and Matsumura 1995), and appetite (Baile et al. 1973). Altered brain AA metabolism has been implicated also in a number of neurological, neurodegenerative, and psychiatric disorders, including epilepsy (McCown et al. 1997), ischemia (Sapirstein and Bonventre 2000b; Phillis and O'Regan 2003), stroke (Dirnagl et al. 1999), HIV-associated dementia (Griffin et al. 1994), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Almer et al. 2001), Alzheimer’s disease (Bazan et al. 2002), Parkinson’s disease (Teismann et al. 2003), schizophrenia (Muller et al. 2002), and mood disorders (Rapoport and Bosetti 2002; Sublette et al. 2004). Additionally, we have demonstrated that the release and/or metabolism of AA to PGE2 via cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2)/COX-2 in rat brain are common targets of therapeutic concentrations of mood-stabilizers used to treat bipolar disorder: lithium, valproic acid, and carbamazepine (Bosetti et al. 2002; Bosetti et al. 2003; Ghelardoni et al. 2004).

Figure 1. The arachidonic acid cascade.

The AA cascade involves the release of AA from membrane phospholipids by a PLA2, followed by its metabolism to bioactive eicosanoids – prostaglandins, leukotrienes and epoxy fatty acids –through COX, lipoxygenase and cytochrome P450 epoxygenase enzymes, respectively.

EETs = epoxyeicosatrienoic acids; HETEs = hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids; HPETE = hydroxyperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid; LOX = lipoxygenase; PG = prostaglandin; TXA2 = thromboxane A2

The regulation of brain AA metabolism and the coupling mechanisms between upstream and downstream enzymes involved in the prostaglandin biosynthetic pathway remain to be fully elucidated. While pharmacological inhibitors can be used to investigate the role of key enzymes involved in brain AA release and metabolism in physiological and pathological models, the lack, in some cases, of specific inhibitors or of a complete pharmacological inhibition, and standardization of dosing paradigms complicate the studies. In this regard, genetic mouse models lacking or over-expressing specific enzymes represent useful tools to identify the individual role of each enzyme and its coupling with the upstream and downstream enzymes in the AA cascade in physiology and pathology.

Genetic mouse models used to investigate the physiological and pathological roles of AA release and metabolism in brain

Cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha knockout (cPLA2α −/−) mice

Among the members of the PLA2 superfamily, cPLA2α preferentially hydrolyzes arachidonoyl phospholipids and is activated by submicromolar concentrations of Ca2+ and by phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinases (Leslie 1997) and protein kinase C-α (Li et al. 2007). The development of mice deficient in cPLA2α (cPLA2α −/−) by Bonventre’s and Shimizu’s groups (Bonventre et al. 1997; Uozumi et al. 1997) has helped to further elucidate the role of cPLA2 in the central nervous system both under basal conditions and in pathological models.

Under basal conditions, although there was no difference in total phosphatidylcholine levels in the cPLA2α −/− mice compared with wild type mice , the brain AA concentration of phosphatidylcholine was significantly reduced in cPLA2α −/−mice (Rosenberger et al. 2003). We reported that cPLA2α −/− mice show a marked decrease in the mRNA and protein levels of COX-2 as well as reduced COX activity, without any change in the expression of COX-1, 5-LOX, or cytochrome P450 epoxygenase, indicating that cPLA2 and COX-2 are functionally coupled for PGE2 biosynthesis (Bosetti and Weerasinghe 2003). Expression and activity of other PLA2 enzymes was not significantly changed in cPLA2α −/− mice, suggesting that type V sPLA2 or type VI iPLA2 do not compensate for the loss of cPLA2 (Bosetti and Weerasinghe 2003). The role of cPLA2 in the transcriptional regulation of COX-2 in brain was also highlighted by work from Sapirstein and colleagues (Sapirstein et al. 2005), who reported that after systemic administration of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), brain COX-2 mRNA levels are ~60% lower in cPLA2α −/− mice, without any significant change in microsomal prostaglandin E synthase (mPGES)-1 mRNA induction. Brain levels of PGE2 also were reduced after LPS injection in cPLA2α −/− mice. Overall, the combined data indicate that cPLA2α plays a significant role in regulating COX-2 gene expression and that COX-2 is the major contributor to brain PGE2 formation.

cPLA2α −/− mice also are less susceptible than wild type mice to cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury after 2 h of middle cerebral occlusion (Bonventre et al. 1997; Tabuchi et al. 2003), with reduced neurological deficits, a reduction in infarct volume, and reduced brain edema compared to wild type mice (Bonventre et al. 1997; Tabuchi et al. 2003). The role of cPLA2 in brain injury has been further investigated using the neurotoxicant 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), which damages substantia nigra neurons and causes a decrease in striatal dopamine concentration and is used as a model of Parkinson’s disease (recently reviewed in (Jakowec and Petzinger 2004)). cPLA2α −/− mice show significantly less depletion of brain striatal dopamine after MPTP administration, suggesting that the increased resistance to MPTP neurotoxicity may be due to reduced release of free fatty acids and formation of lysophospholipids, as well as reduced production of reactive oxidative species via subsequent COX metabolism of AA (Klivenyi et al. 1998). Although the susceptibility of cPLA2−/− mice has not been investigated in other models of neurotoxicity, data currently available suggest that pharmacological inhibition of cPLA2 may be promising in the treatment of neuroinflammation, ischemic brain damage, and possibly, Parkinson’s disease.

It should be taken into consideration that the mouse strains C57Bl/6n and 129/Sv have a naturally occurring missense mutation in the gene encoding for the type IIA sPLA2. Consequently, cPLA2α −/− mice, as well as their respective wild type mice, are deficient in type IIA sPLA2 (Kennedy et al. 1995; Sapirstein and Bonventre 2000a). Although type IIA sPLA2 is more abundantly expressed in the rat, whereas in the mouse the sPLA2 isoform expressed at higher levels is type V sPLA2 (Sawada et al. 1999), it would be worthwhile to identify how and to what extent sPLA2 IIA genetic deletion contributes to the phenotype of cPLA2α −/− mice. In this regard, transgenic mice overexpressing human sPLA2-IIA are available (Grass et al. 1996) and could be used to identify the function of sPLA2-IIA in the central nervous system in physiological and pathological conditions. In this regard, a recent report indicates up-regulated PLA2-IIA mRNA brain expression and increased number of sPLA2-IIA-immunoreactive astrocytes in the hippocampus and inferior temporal gyrus in Alzheimer's disease (AD) brains as compared to controls (Moses et al. 2006).

Cyclooxygenase-2 knockout mice

COX-2−/− mice share some phenotypic similarities with cPLA2−/− mice, such as profound defects in female fertility (Morham et al. 1995; Bonventre et al. 1997), decreased susceptibility to ischemia/reperfusion brain injury (Bonventre et al. 1997; Sapirstein and Bonventre 2000b; Tabuchi et al. 2003), and MPTP-induced neurotoxicity (Klivenyi et al. 1998). These similarities between the two genotypes further support the evidence of a functional coupling between cPLA2 and COX-2 enzymes (Naraba et al. 1998; Scott et al. 1999; Takano et al. 2000; Bosetti and Weerasinghe 2003).

Under basal conditions, the COX-2−/− mouse brain shows altered brain lipid composition, including an increase in phosphatidyl serine and reduction in cholesterol (Ma et al. 2007), an upregulation of the activity and expression of the upstream Ca2+-dependent PLA2 enzymes, cPLA2 and sPLA2, as well as a compensatory increase in the expression of the reciprocal isoenzyme, COX-1 (Bosetti et al. 2004). The increase in PLA2 activity is consistent with a baseline elevation in AA incorporation coefficients (k*) in most brain regions, reflecting higher rates of AA loss in brain in COX-2−/− mice compared to wild type mice (Basselin et al. 2006). Despite the compensatory increase in COX-1 expression, brain PGE2 level is decreased by about 50% in the COX-2−/−compared to wild type mice, further supporting the notion that COX-2 plays a major role in endogenous PGE2 synthesis (Bosetti et al. 2004).

COX-2−/− mice show a decrease in brain nuclear factor-κ B (NF-κ B) DNA-protein binding activity, likely caused by the decrease in the protein levels of p65, phosphorylated p65 and phosphorylated I-κ Bα (Rao et al. 2005). These changes in the NF-κ B transcription factor suggest that COX-2 deletion may in turn have profound transcriptional effects. Thus, we examined gene expression in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of mice deficient in either COX-1 or COX-2. We found that COX-1−/− or COX-2−/− mice show significant changes in the expression of a multitude of genes in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex, with some occurring in both genotypes but most changes (>93–97%) being unique to one isoform deletion and not the other. The major function category affected by either COX-1 or COX-2 deficiency is transcriptional regulation, suggesting that COX end products can modulate gene expression. We also showed that the expression of genes constituting at least 5% of the total number of genes affected was involved in transmembrane and mitochondrial functions in the cerebral cortex of COX-2−/− but not COX-1−/− mice (Toscano et al. 2007).

Iadecola’s group demonstrated that constitutively expressed COX-2 plays a key role in the mechanisms coupling synaptic activity to neocortical blood flow. They show that selective COX-2 inhibition or genetic deletion of COX-2 attenuates the increase in cerebral blood flow produced by somatosensory activation. Vasodilator responses of the cerebral circulation to stimuli not dependant on neuronal activity, such as hypercapnia or topical application of acetylcholine or bradykinin, were not influenced by NS-398 and were preserved in COX-2−/− mice (Niwa et al. 2000).

COX-2 seems to play a key role in the cholinergic signaling in brain as the AA incorporation response to arecoline, evident in wild type mice at sites of muscarinic receptors, is entirely absent in COX-2−/− mice, suggesting that COX-2 is required for muscarinic receptor activation (Basselin et al. 2006). This implies that the response to arecoline mediated by M1,3,5 receptors coupled to PLA2 largely reflects the conversion of released AA to prostanoids by COX-2 (Basselin et al. 2006).

Because COX-2 is thought to be implicated in a number of neurological and neurodegenerative diseases, COX-2−/− mice also have been used to investigate the role of COX-2 in different neurotoxic models. Similarly to cPLA2−/− mice, COX-2−/− mice also are more resistant to MPTP-mediated neurotoxicity, showing a reduced loss of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta compared to wild type mice (Feng et al. 2002; Feng et al. 2003).

Iadecola and colleagues showed that brain injury produced by middle cerebral artery occlusion or following NMDA microinjection in the neocortex is reduced in COX-2−/− compared to wild type mice (Iadecola et al. 2001b). They further reported that the lesion size produced by direct injection of NMDA in the somatosensory cortex is attenuated in COX-2−/− mice and they determined, using COX-2−/− mice and the COX-2 selective inhibitor NS-398, that COX-2 is not a major source of oxygen radicals after cerebral ischemia, suggesting that other COX-2 reaction products, including prostanoids or non-oxygen-based radicals may be responsible for brain injury (Kunz et al. 2006). In a model of post-ischemic brain injury after bilateral common carotid artery occlusion, COX-2−/− mice also have reduced ischemic neuronal damage, measured by cresyl violet and TUNEL staining, in the hippocampus (Sasaki et al. 2004).

The role of PGE2 or in general of COX-2 mediated prostaglandin metabolism in mediating or attenuating glutamate excitotoxicity and in kainic acid-mediated excitotoxic brain damage remains controversial. Several studies indicate that PGE2 enhances glutamate release and excitatory amino acid-induced synaptic depolarization (Kimura et al. 1985; Sekiyama et al. 1995; Bezzi et al. 1998; Sanzgiri et al. 1999; Katafuchi et al. 2005). Furthermore, a recent report suggests that COX-2−/− mice may have decreased PGE2 release and reduced neuronal loss after direct microinjection of kainic acid in the CA3 region of the hippocampus (Takemiya et al. 2006). However, since that study did not report neuronal count under basal conditions, it cannot be excluded that COX-2−/− mice show decreased neuronal count independently of kainic acid injection. On the other hand, other studies suggest that PGE2 is protective against glutamate toxicity (Akaike et al. 1994; Cazevieille et al. 1994) and data from our lab indicate that when kainate is administered systemically by intraperitoneal injection, COX-2−/− mice exhibit significantly higher seizure intensities in the 2 h following injection. Increased seizure intensity is accompanied by increased neuronal damage 24 h and after injection of kainate (Toscano and Bosetti, unpublished data).

Data from our group also suggest that COX-2−/− mice show a higher neuroinflammatory response than wild type mice after acute intracerebroventricular injection of LPS, with increased activation of microglia and astrocytes and increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α , and PGE2 (Aid et al., unpublished data). These data agree with evidence that the COX-2 selective inhibitor NS-398 significantly increases the ability of LPS to trigger an innate immune response (Blais et al. 2005).

COX-2 overexpressing mice

Two independent transgenic mouse models with neuronal overexpression of the human COX-2 developed by Pasinetti’s (Kelley et al. 1999) and Andreasson’s groups (Andreasson et al. 2001) have been used to investigate how COX-2 modulates the susceptibility to brain injury. COX-2 transgenic mice show increased lethality following intracerebroventricular injection of kainic acid (Kelley et al. 1999), suggesting that COX-2 may be detrimental to neurons after direct injection of kainate. This observation may be related to a difference in prostaglandin profile in COX-2 overexpressing mice, or to the neuronal localization of overexpressed COX-2. Transgenic mice overexpressing functional COX-2 in neurons of the hippocampus, cortex, and amygdala also develop age-dependent cognitive deficits that are associated with a parallel age-dependent increase in glial fibrillary acidic protein and neuronal apoptosis (Andreasson et al. 2001). Opposite to the reduced susceptibility to ischemic brain injury of COX-2−/− mice, a significant increase in infarct size was observed after middle cerebral artery occlusion in COX-2 transgenic mice, suggesting that chronic increases in COX-2 expression and enzymatic activity, which can occur in pathological states characterized by oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, could negatively affect neuronal survival in cerebrovascular disease (Dore et al. 2003).

COX-1 knockout mice

Like COX-2−/− mice, COX-1−/− mice have up-regulated brain expression and activity of Ca2+-dependent cPLA2 and sPLA2, as well as an increase in the reciprocal isozyme, COX-2 (Choi et al. 2006). In contrast to COX-2−/− mice, COX-1−/− mice have increased brain levels of PGE2 and increased activation of NF-κ B, which involves the up-regulation of protein expression of the p50 and p65 subunits of NF-κ B, as well as increased protein levels of phosphorylated Iκ Bα and of phosphorylated IKK (Iκ B kinase) α/β (Choi et al. 2006), suggesting that the two isoforms have unique and distinct functions in brain AA metabolism, and that a deficiency of one cannot be compensated for by overexpression of the other. Microarray analysis identified 94 genes differentially expressed in the cerebral cortex and 182 genes differentially expressed in the hippocampus of COX-1−/− mice compared to wild type mice. The expression of genes belonging to the functional group of kinases (> 5% of total number of genes) was selectively changed in the hippocampus of COX-1−/− but not of COX-2−/− mice (Toscano et al. 2007). In both COX-1−/− and COX-2−/− mice, the greatest number of genes whose expression was significantly changed in both brain regions belonged to the function category of transcriptional regulation (Toscano et al. 2007). Although some of the molecular mechanisms underlying these changes are not understood at this time, these data indicate that the two COX- isoforms have some independent effects on modulating gene expression.

COX-1 plays an important role in the maintenance of resting cerebral blood flow and in the vasodilation produced by selected endothelium-dependent vasodilators or hypercapnia (Niwa et al. 2001). Indeed, COX-1−/− mice show up to 20% decrease in resting cerebral blood flow in selected telencephalic regions and attenuated responses to hypercapnia, bradykinin, AA, and the calcium ionophore A23187, whereas responses to acetylcholine, vibrissal stimulation, and S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine are not affected (Niwa et al. 2001).

The differences between COX-1−/− and COX-2−/− mice are even more dramatic in the response to neurotoxic insults (Table 1). Whereas COX-2−/− mice show increased protection against ischemic brain injury or and MPTP-induced neurotoxicity (Iadecola et al. 2001b; Feng et al. 2002; Feng et al. 2003), COX-1−/− mice either show no difference compared to wild type mice (Cheung et al. 2002; Feng et al. 2003) or, in case of ischemia-reperfusion, they seem to be even more susceptible (Iadecola et al. 2001a).

Table 1.

Phenotypes of cPLA2-, COX-1- or COX-2-deficient mice under basal conditions or upon different neurotoxic injuries.

| BASAL | cPLA2−/− | COX-1−/− | COX-2−/− |

|---|---|---|---|

| cPLA2 expression | n.d.(Bonventre et al. 1997; Bosetti and Weerasinghe 2003) | ↑ (Choi et al. 2006) | ↑ (Bosetti et al. 2004) |

| sPLA2 expression | ↔(Bosetti and Weerasinghe 2003) | ↑ (Choi et al. 2006) | ↑ (Bosetti et al. 2004) |

| COX-1 expression | ↔ (Bosetti and Weerasinghe 2003) | n.d.(Choi et al. 2006) | ↑ (Bosetti et al. 2004) |

| COX-2 expression | ↓ (Bosetti and Weerasinghe 2003) | ↑ (Choi et al. 2006) | n.d. (Bosetti et al. 2004). |

| NF-κB activity | unknown | ↑ (Choi et al. 2006) | ↓ (Rao et al. 2005) |

| PGE2 levels | ↔ (basal)(Sapirstein et al. 2005)

↓ (after LPS)(Sapirstein et al. 2005) |

↑ (Choi et al. 2006) | ↓ (Bosetti et al. 2004) |

| SUSCEPTIBILITY TO NEUROTOXIC INJURY | |||

| Ischemia/Reperfusion | ↓ (Bonventre et al. 1997; Sapirstein and Bonventre 2000b; Tabuchi et al. 2003) | ↑ (Iadecola et al. 2001a)

↔ (Cheung et al. 2002) |

↓ (Iadecola et al. 2001b) |

| MPTP-neurotoxicity | ↓ (Klivenyi et al. 1998) | ↔ (Feng et al. 2002) | ↓ (Feng et al. 2003) |

| LPS- neuroinflammation | ↓ (Sapirstein et al. 2005) | ↓ (Choi et al. unpublished) | ↑ (Aid et al., unpublished) |

| NMDA-icv induced cortical lesion | unknown | unknown | ↓ (Iadecola et al. 2001b) |

| Kainic acid-induced seizures | unknown | ↔ (Toscano et al., unpublished) | ↑ (Toscano et al., unpublished) |

| Kainic acid-induced neuronal damage | unknown | ↔ (Toscano et al., unpublished) | ↑ ip (Toscano et al., unpublished)

↓ icv (Takemiya et al. 2006) |

Although the susceptibility of COX-1−/− mice to kainate-induced seizures and neuronal damage needs to be fully elucidated, preliminary results from our group indicate that the susceptibility of COX-1−/− mice to 10 mg/kg of kainate, a dose that causes seizures and hippocampal neuronal damage in the COX-2−/− mice, is not significantly different compared to wild type mice (Toscano and Bosetti, unpublished data). While COX-1−/− mice do not show increase resistance to most of the brain insults examined, data from our lab indicate that COX-1−/− mice have a reduced neuroinflammatory response and protein oxidative damage after acute intracerebroventricular injection of LPS (Choi et al., unpublished data). Therefore, it is very important to elucidate the specific roles that COX-1 and COX-2 play in the neuroinflammatory cascade of events that lead to brain injury.

mPGES-1 knockout mice

The contribution of mPGES-1 to brain PGE2 production in response to LPS has been examined using mPGES-1−/− mice (Ikeda-Matsuo et al. 2005). Following the injection of LPS into the substantia nigra, which contains a high density of microglia, mPGES-1 expression is specifically induced in activated microglia at the site of the localized inflammatory response. mPGES-1 deficiency completely abolished LPS-stimulated PGE2 production in microglial cells (Ikeda-Matsuo et al. 2005). Constitutive expression of mPGES-2, cytosolic PGES (cPGES) and COX-1 is not significantly different in mPGES-1−/− derived and wild-type derived microglia, indicating that mPGES-1 deficiency does not affect the expression of other enzymes involved in PGE2 biosynthesis (Ikeda-Matsuo et al. 2005).

PGD2 receptor (DP) knockout mice

Using both PGDS−/− and DP−/− mice, Mohri and colleagues demonstrated that PGD2 plays an important role in microglia/astrocyte interaction and is involved in the pathological response to demyelination in twitcher mice, a model of human Krabbe's disease (Mohri et al. 2006). Specifically, PGDS−/− or DP1−/− twitcher mice showed a remarkable suppression of astrogliosis and demyelination, as well as a reduction in twitching and spasticity.

The PGD2/DP axis also has an important physiological role in non-rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, as demonstrated by the observation that infusion of PGD2 into the lateral ventricle of the brain increased the amount of non-REM sleep in wild type but not in DP−/− mice (Mizoguchi et al. 2001).

PGE2 receptors (EP1-4) knockout mice

The development of mice lacking the different subtypes of the G-protein-coupled receptors for PGE2 - EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4 - (Ushikubi et al. 1998) helped to further understand the physiological or pathological roles of these receptors. A number of studies using EP1−/− mice indicate that the prostaglandin EP1 receptor mediates neurotoxicity after NMDA-induced excitotoxicity, oxygen glucose deprivation, or focal ischemia (Ahmad et al. 2006; Kawano et al. 2006). EP1−/− mice also demonstrate behavioral abnormalities, including increased impulsive aggression, reduced social interaction, enhanced acoustic startle response, and jumping behavior in the cliff-avoidance test under conditions of social or environmental stress, suggesting that EP1 selective agonists might be used to treat impulsive behavior (Matsuoka et al. 2005). EP1−/− and EP3−/− mice also show impaired HPA activation after i.p. LPS injection, with a significant decrease in plasma levels of ACTH compared to wild type mice (Matsuoka et al. 2003).

The role of the EP2 receptor as elucidated with EP2−/− mice appears to be more complex. Microglial EP2 has been shown to be critical to neuronal damage from activation of cerebral innate immunity involving COX-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (Montine et al. 2002; Shie et al. 2005). On the other hand, the EP2 receptor has been shown to mediate neuroprotection in an organotypic hippocampal model of NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity and in permanent focal ischemia induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion (Liu et al. 2005). The EP2 receptor mediates protection also in a chronic model of excitotoxic motor neuron degeneration (Bilak et al. 2004), as well as in β -amyloid neurotoxicity (Yagami et al. 2003) and neuroinflammation (Kim et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2004).

EP3 receptors, but not the other subtypes of EP receptors, play important roles in mediating the febrile response after PGE2, IL-1β , or LPS (Ushikubi et al. 1998), by generating hyperthermia (Lazarus 2006). EP3 receptors are also involved in the ACTH response to bacterial LPS (Matsuoka et al. 2003).

Stimulation of EP4 receptors has been shown to protect cultured neurons against oxidative stress and cell death induced by β -amyloid exposure (Echeverria et al. 2005). In opposition to EP3 receptors, EP4 responses generate hypothermia (Lazarus 2006) and have been reported to activate the histaminergic system to mediate PGE2- induced wakefulness (Huang et al. 2003). Since most EP4−/− mice die during the neonatal period (Nguyen et al. 1997; Segi et al. 1998), data on the effect of EP4 receptor deletion in brain physiological or pathological conditions are lacking.

LOX knockout mice

ApoE−/− mice crossbred with 12/15-LOX−/− mice have significantly reduced markers of lipid peroxidation and of protein oxidation when compared with 12/15-LOX-expressing controls, indicating that 12/15-LOX modulates oxidative reactions in the central nervous system (Chinnici et al. 2005). Consistent with this observation, 12/15-LOX−/−mice appear to be protected against neuronal cell death and oxidative stress caused by transient focal ischemia (van Leyen et al. 2006). Additionally, neurons isolated from 12-LOX−/− mice are resistant to glutamate-induced death, suggesting an involvement of 12-LOX in glutamate-induced neurodegeneration (Khanna et al. 2003).

On the other hand, the involvement of 5-LOX in ischemic brain injury remains to be clarified. While Kitagawa and colleagues showed that 5-LOX−/− and wild type mice do not differ significantly in brain infarct size following permanent and transient 60 min ischemia, suggesting that 5-LOX-derived leukotrienes are not involved in infarct expansion in focal cerebral ischemia (Kitagawa et al. 2004), a recent report indicates that 5-LOX inhibitors protect brain in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemic injury (Jatana et al. 2006). 5-LOX−/− mice show increased resistance to traumatic spinal cord injury by showing a marked decrease in neutrophils infiltration, cytokine expression apoptosis, and histological damage and ameliorated motor recovery as compared to wild-type mice (Genovese et al. 2005). 5-LOX may also be implicated in affective behaviors, as 5-LOX−/−mice show reduced anxiety-like behavior in various behavioral tests (Uz et al. 2002).

Conclusions

The use of genetically altered mouse models lacking specific enzymes of the AA cascade has helped to identify the metabolic coupling of these enzymes and their distinct roles in brain physiological conditions as well as in models of neurotoxicity. A summary of the different phenotypes under basal conditions and after different neurotoxic challenges is shown in Table 1. The data obtained under basal conditions indicate that cPLA2 and COX-2 are functionally coupled in the synthesis of endogenous brain PGE2 (Bosetti and Weerasinghe 2003; Bosetti et al. 2004).

Both cPLA2−/− and COX-2−/− mice exhibit decreased susceptibility to ischemic brain injury (Bonventre et al. 1997; Iadecola et al. 2001b) and MPTP-induced neurotoxicity (Klivenyi et al. 1998; Feng et al. 2003). However, our data with acute LPS-induced neuroinflammation and kainic-acid-induced seizures and neuronal damage indicate that COX-2−/− mice are more vulnerable than wild-type mice (Aid et al., unpublished data; Toscano and Bosetti, unpublished data). Therefore, it is quite possible that the increased or decreased susceptibility to neurotoxicity of COX-2−/− mice is stimulus-specific. While COX-1−/− mice do not appear to respond differently to most of the neurotoxic stimuli investigated (Cheung et al. 2002; Feng et al. 2002); Toscano and Bosetti, unpublished data), their decreased neuroinflammatory response to acute LPS (Choi et al., unpublished data) suggests that COX-1 plays a role in initiating the neuroinflammatory cascade, likely because of its preferential localization in microglial cells (Yermakova et al. 1999; Ballou 2000; Schwab et al. 2002). Not only do these observations demonstrate that COX-1 and COX-2 have unique roles in brain physiology, but being that neuroinflammation is a key component of some neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, our findings may have therapeutic implications. As recently noted by McGeer and Mc Geer, reactive microglia expressing COX-1 is the proper target for inflammatory suppression (Hoozemans et al. 2002), suggesting that non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with predominant COX-1 rather than COX-2 inhibition may be more effective in reducing brain inflammation (McGeer and McGeer 2006).

In summary, although data obtained in genetically altered mouse models should be interpreted with care because of possible compensatory changes, knockout and transgenic mice provide a useful approach to identify the roles of specific enzymes of the AA cascade in physiological and pathological models. Therefore, these genetic animal models combined with conditional knockouts, models of in vivo RNA interference, and the use of specific pharmacological inhibitors, may help to develop novel therapeutic strategies for diseases involving altered brain AA metabolism.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. I thank Drs. Christopher Toscano, Saba Aid, and Mireille Basselin for critical comments.

References

- Ahmad AS, Saleem S, Ahmad M, Dore S. Prostaglandin EP1 receptor contributes to excitotoxicity and focal ischemic brain damage. Toxicol Sci. 2006;89:265–270. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaike A, Kaneko S, Tamura Y, Nakata N, Shiomi H, Ushikubi F, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E2 protects cultured cortical neurons against N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated glutamate cytotoxicity. Brain Res. 1994;663:237–243. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almer G, Guegan C, Teismann P, Naini A, Rosoklija G, Hays AP, Chen C, Przedborski S. Increased expression of the proinflammatory enzyme cyclooxygenase-2 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:176–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson KI, Savonenko A, Vidensky S, Goellner JJ, Zhang Y, Shaffer A, Kaufmann WE, Worley PF, Isakson P, Markowska AL. Age-dependent cognitive deficits and neuronal apoptosis in cyclooxygenase-2 transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8198–8209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08198.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baile CA, Simpson CW, Bean SM, McLaughlin CL, Jacobs HL. Prostaglandins and food intake of rats: a component of energy balance regulation? Physiol Behav. 1973;10:1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(73)90191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballou LR. The regulation of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in knockout cells and cyclooxygenase and fever in knockout mice. Ernst Schering Res Found Workshop. 2000:97–124. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-04047-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basselin M, Villacreses NE, Langenbach R, Ma K, Bell JM, Rapoport SI. Resting and arecoline-stimulated brain metabolism and signaling involving arachidonic acid are altered in the cyclooxygenase-2 knockout mouse. J Neurochem. 2006;96:669–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan NG, Colangelo V, Lukiw WJ. Prostaglandins and other lipid mediators in Alzheimer's disease. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:197–210. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzi P, Carmignoto G, Pasti L, Vesce S, Rossi D, Rizzini BL, Pozzan T, Volterra A. Prostaglandins stimulate calcium-dependent glutamate release in astrocytes. Nature. 1998;391:281–285. doi: 10.1038/34651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilak M, Wu L, Wang Q, Haughey N, Conant K, St Hillaire C, Andreasson K. PGE2 receptors rescue motor neurons in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:240–248. doi: 10.1002/ana.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais V, Turrin NP, Rivest S. Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibition increases the inflammatory response in the brain during systemic immune stimuli. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1563–1574. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonventre JV, Huang Z, Taheri MR, O'Leary E, Li E, Moskowitz MA, Sapirstein A. Reduced fertility and postischaemic brain injury in mice deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nature. 1997;390:622–625. doi: 10.1038/37635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti F, Weerasinghe GR. The expression of brain cyclooxygenase-2 is down-regulated in the cytosolic phospholipase A2 knockout mouse. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1471–1477. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti F, Langenbach R, Weerasinghe GR. Prostaglandin E2 and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-2 expression are decreased in the cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mouse brain despite compensatory induction of cyclooxygenase-1 and Ca2+-dependent phospholipase A2. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1389–1397. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti F, Weerasinghe GR, Rosenberger TA, Rapoport SI. Valproic acid down-regulates the conversion of arachidonic acid to eicosanoids via cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2003;85:690–696. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti F, Rintala J, Seemann R, Rosenberger TA, Contreras MA, Rapoport SI, Chang MC. Chronic lithium downregulates cyclooxygenase-2 activity and prostaglandin E(2) concentration in rat brain. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:845–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazevieille C, Muller A, Meynier F, Dutrait N, Bonne C. Protection by prostaglandins from glutamate toxicity in cortical neurons. Neurochem Int. 1994;24:395–398. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman V, Dickenson AH. The spinal and peripheral roles of bradykinin and prostaglandins in nociceptive processing in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;219:427–433. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90484-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung RT, Pei Z, Feng ZH, Zou LY. Cyclooxygenase-1 gene knockout does not alter middle cerebral artery occlusion in a mouse stroke model. Neurosci Lett. 2002;330:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00738-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnici CM, Yao Y, Ding T, Funk CD, Pratico D. Absence of 12/15 lipoxygenase reduces brain oxidative stress in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1371–1377. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61224-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH, Langenbach R, Bosetti F. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 enzymes differentially regulate the brain upstream NF-kappaB pathway and downstream enzymes involved in prostaglandin biosynthesis. J Neurochem. 2006;98:801–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U, Iadecola C, Moskowitz MA. Pathobiology of ischaemic stroke: an integrated view. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:391–397. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore S, Otsuka T, Mito T, Sugo N, Hand T, Wu L, Hurn PD, Traystman RJ, Andreasson K. Neuronal overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 increases cerebral infarction. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:155–162. doi: 10.1002/ana.10612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria V, Clerman A, Dore S. Stimulation of PGE receptors EP2 and EP4 protects cultured neurons against oxidative stress and cell death following beta-amyloid exposure. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2199–2206. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Li D, Fung PC, Pei Z, Ramsden DB, Ho SL. COX-2-deficient mice are less prone to MPTP-neurotoxicity than wild-type mice. Neuroreport. 2003;14:1927–1929. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200310270-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng ZH, Wang TG, Li DD, Fung P, Wilson BC, Liu B, Ali SF, Langenbach R, Hong JS. Cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice are resistant to 1-methyl-4-phenyl1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine-induced damage of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Neurosci Lett. 2002;329:354–358. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00704-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick FA, Soberman R. Regulated formation of eicosanoids. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1347–1351. doi: 10.1172/JCI13241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese T, Mazzon E, Rossi A, Di Paola R, Cannavo G, Muia C, Crisafulli C, Bramanti P, Sautebin L, Cuzzocrea S. Involvement of 5-lipoxygenase in spinal cord injury. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;166:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghelardoni S, Tomita YA, Bell JM, Rapoport SI, Bosetti F. Chronic carbamazepine selectively downregulates cytosolic phospholipase A(2) expression and cyclooxygenase activity in rat brain. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grass DS, Felkner RH, Chiang MY, Wallace RE, Nevalainen TJ, Bennett CF, Swanson ME. Expression of human group II PLA2 in transgenic mice results in epidermal hyperplasia in the absence of inflammatory infiltrate. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2233–2241. doi: 10.1172/JCI118664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin DE, Wesselingh SL, McArthur JC. Elevated central nervous system prostaglandins in human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:592–597. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayaishi O, Matsumura H. Prostaglandins and sleep. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1995;5:211–216. doi: 10.1016/0960-5428(95)00010-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJ, Veerhuis R, Janssen I, van Elk EJ, Rozemuller AJ, Eikelenboom P. The role of cyclo-oxygenase 1 and 2 activity in prostaglandin E(2) secretion by cultured human adult microglia: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2002;951:218–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T, Oka T, Hosoi M, Aou S. Pain modulatory actions of cytokines and prostaglandin E2 in the brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:269–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZL, Sato Y, Mochizuki T, Okada T, Qu WM, Yamatodani A, Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Prostaglandin E2 activates the histaminergic system via the EP4 receptor to induce wakefulness in rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5975–5983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-14-05975.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Sugimoto K, Niwa K, Kazama K, Ross ME. Increased susceptibility to ischemic brain injury in cyclooxygenase-1-deficient mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001a;21:1436–1441. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Niwa K, Nogawa S, Zhao X, Nagayama M, Araki E, Morham S, Ross ME. Reduced susceptibility to ischemic brain injury and N-methyl-D-aspartate-mediated neurotoxicity in cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001b;98:1294–1299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda-Matsuo Y, Ikegaya Y, Matsuki N, Uematsu S, Akira S, Sasaki Y. Microglia-specific expression of microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 contributes to lipopolysaccharide-induced prostaglandin E2 production. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1546–1558. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakowec MW, Petzinger GM. 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-lesioned model of parkinson's disease, with emphasis on mice and nonhuman primates. Comp Med. 2004;54:497–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatana M, Giri S, Ansari MA, Elango C, Singh AK, Singh I, Khan M. Inhibition of NF-kappaB activation by 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors protects brain against injury in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katafuchi T, Duan S, Take S, Yoshimura M. Modulation of glutamate-induced outward current by prostaglandin E(2) in rat dissociated preoptic neurons. Brain Res. 2005;1037:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WE, Worley PF, Pegg J, Bremer M, Isakson P. COX-2, a synaptically induced enzyme, is expressed by excitatory neurons at postsynaptic sites in rat cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2317–2321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Anrather J, Zhou P, Park L, Wang G, Frys KA, Kunz A, Cho S, Orio M, Iadecola C. Prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptors: downstream effectors of COX-2 neurotoxicity. Nat Med. 2006;12:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nm1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley KA, Ho L, Winger D, Freire-Moar J, Borelli CB, Aisen PS, Pasinetti GM. Potentiation of excitotoxicity in transgenic mice overexpressing neuronal cyclooxygenase-2. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BP, Payette P, Mudgett J, Vadas P, Pruzanski W, Kwan M, Tang C, Rancourt DE, Cromlish WA. A natural disruption of the secretory group II phospholipase A2 gene in inbred mouse strains. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22378–22385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna S, Roy S, Ryu H, Bahadduri P, Swaan PW, Ratan RR, Sen CK. Molecular basis of vitamin E action: tocotrienol modulates 12-lipoxygenase, a key mediator of glutamate-induced neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43508–43515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307075200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Kwon KJ, Park JY, Lee SH, Moon CH, Baik EJ. Neuroprotective effects of prostaglandin E2 or cAMP against microglial and neuronal free radical mediated toxicity associated with inflammation. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:97–107. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Okamoto K, Sakai Y. Modulatory effects of prostaglandin D2, E2 and F2 alpha on the postsynaptic actions of inhibitory and excitatory amino acids in cerebellar Purkinje cell dendrites in vitro. Brain Res. 1985;330:235–244. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90682-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa K, Matsumoto M, Hori M. Cerebral ischemia in 5-lipoxygenase knockout mice. Brain Res. 2004;1004:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klivenyi P, Beal MF, Ferrante RJ, Andreassen OA, Wermer M, Chin MR, Bonventre JV. Mice deficient in group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2 are resistant to MPTP neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 1998;71:2634–2637. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71062634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz A, Anrather J, Zhou P, Orio M, Iadecola C. Cyclooxygenase-2 does not contribute to postischemic production of reactive oxygen species. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006 Jul 5; doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600369. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus M. The differential role of prostaglandin E2 receptors EP3 and EP4 in regulation of fever. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2006;50:451–455. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EO, Shin YJ, Chong YH. Mechanisms involved in prostaglandin E2-mediated neuroprotection against TNF-alpha: possible involvement of multiple signal transduction and beta-catenin/T-cell factor. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;155:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerea LS, McNamara JO. Ionotropic glutamate receptor subtypes activate c-fos transcription by distinct calcium-requiring intracellular signaling pathways. Neuron. 1993;10:31–41. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90239-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerea LS, Carlson NG, Simonato M, Morrow JD, Roberts JL, McNamara JO. Prostaglandin F2alpha is required for NMDA receptor-mediated induction of c-fos mRNA in dentate gyrus neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:117–124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00117.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie CC. Properties and regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16709–16712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DY, Hardy P, Abran D, Martinez-Bermudez AK, Guerguerian AM, Bhattacharya M, Almazan G, Menezes R, Peri KG, Varma DR, Chemtob S. Key role for cyclooxygenase-2 in PGE2 and PGF2alpha receptor regulation and cerebral blood flow of the newborn. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R1283–1290. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.4.R1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Subbulakshmi V, Oldfield CM, Aamir R, Weyman CM, Wolfman A, Cathcart MK. PKCalpha regulates phosphorylation and enzymatic activity of cPLA2 in vitro and in activated human monocytes. Cell Signal. 2007;19:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Wu L, Breyer R, Mattson MP, Andreasson K. Neuroprotection by the PGE2 EP2 receptor in permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:758–761. doi: 10.1002/ana.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Langenbach R, Rapoport SI, Basselin M. Altered brain lipid composition in cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 knockout mouse. J Lipid Res. 2007 Jan 3; doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600400-JLR200. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka Y, Furuyashiki T, Yamada K, Nagai T, Bito H, Tanaka Y, Kitaoka S, Ushikubi F, Nabeshima T, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptor EP1 controls impulsive behavior under stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16066–16071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504908102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka Y, Furuyashiki T, Bito H, Ushikubi F, Tanaka Y, Kobayashi T, Muro S, Satoh N, Kayahara T, Higashi M, Mizoguchi A, Shichi H, Fukuda Y, Nakao K, Narumiya S. Impaired adrenocorticotropic hormone response to bacterial endotoxin in mice deficient in prostaglandin E receptor EP1 and EP3 subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4132–4137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0633341100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCown TJ, Knapp DJ, Crews FT. Inferior collicular seizure generalization produces site-selective cortical induction of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) Brain Res. 1997;767:370–374. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00773-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG. NSAIDs and Alzheimer disease: Epidemiological, animal model and clinical studies. Neurobiol Aging. 2006 May 10; doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.03.013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi A, Eguchi N, Kimura K, Kiyohara Y, Qu WM, Huang ZL, Mochizuki T, Lazarus M, Kobayashi T, Kaneko T, Narumiya S, Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Dominant localization of prostaglandin D receptors on arachnoid trabecular cells in mouse basal forebrain and their involvement in the regulation of non-rapid eye movement sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11674–11679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201398898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohri I, Taniike M, Taniguchi H, Kanekiyo T, Aritake K, Inui T, Fukumoto N, Eguchi N, Kushi A, Sasai H, Kanaoka Y, Ozono K, Narumiya S, Suzuki K, Urade Y. Prostaglandin D2-mediated microglia/astrocyte interaction enhances astrogliosis and demyelination in twitcher. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4383–4393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4531-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine TJ, Milatovic D, Gupta RC, Valyi-Nagy T, Morrow JD, Breyer RM. Neuronal oxidative damage from activated innate immunity is EP2 receptor-dependent. J Neurochem. 2002;83:463–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morham SG, Langenbach R, Loftin CD, Tiano HF, Vouloumanos N, Jennette JC, Mahler JF, Kluckman KD, Ledford A, Lee CA, et al. Prostaglandin synthase 2 gene disruption causes severe renal pathology in the mouse. Cell. 1995;83:473–482. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses GS, Jensen MD, Lue LF, Walker DG, Sun AY, Simonyi A, Sun GY. Secretory PLA2-IIA: a new inflammatory factor for Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2006;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller N, Riedel M, Scheppach C, Brandstatter B, Sokullu S, Krampe K, Ulmschneider M, Engel RR, Moller HJ, Schwarz MJ. Beneficial antipsychotic effects of celecoxib add-on therapy compared to risperidone alone in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1029–1034. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naraba H, Murakami M, Matsumoto H, Shimbara S, Ueno A, Kudo I, Ohishi S. Segregated coupling of phospholipases A2, cyclooxygenases, and terminal prostanoid synthases in different phases of prostanoid biosynthesis in rat peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1998;160:2974–2982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M, Camenisch T, Snouwaert JN, Hicks E, Coffman TM, Anderson PA, Malouf NN, Koller BH. The prostaglandin receptor EP4 triggers remodelling of the cardiovascular system at birth. Nature. 1997;390:78–81. doi: 10.1038/36342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa K, Haensel C, Ross ME, Iadecola C. Cyclooxygenase-1 participates in selected vasodilator responses of the cerebral circulation. Circ Res. 2001;88:600–608. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.6.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa K, Araki E, Morham SG, Ross ME, Iadecola C. Cyclooxygenase-2 contributes to functional hyperemia in whisker-barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 2000;20:763–770. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00763.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda SR, Urbanski HF, Junier MP, Capdevila J. The role of arachidonic acid and its metabolites in the release of neuropeptides. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;559:192–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb22609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillis JW, O'Regan MH. The role of phospholipases, cyclooxygenases, and lipoxygenases in cerebral ischemic/traumatic injuries. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2003;15:61–90. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v15.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard JD. Role of prostaglandins and arachidonic acid derivatives in the coupling of cerebral blood flow to cerebral metabolism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1981;1:361–384. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1981.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JS, Langenbach R, Bosetti F. Down-regulation of brain nuclear factor-kappa B pathway in the cyclooxygenase-2 knockout mouse. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;139:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport SI, Bosetti F. Do lithium and anticonvulsants target the brain arachidonic acid cascade in bipolar disorder? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:592–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger TA, Villacreses NE, Contreras MA, Bonventre JV, Rapoport SI. Brain lipid metabolism in the cPLA2 knockout mouse. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:109–117. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200298-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanzgiri RP, Araque A, Haydon PG. Prostaglandin E(2) stimulates glutamate receptor-dependent astrocyte neuromodulation in cultured hippocampal cells. J Neurobiol. 1999;41:221–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapirstein A, Bonventre JV. Specific physiological roles of cytosolic phospholipase A(2) as defined by gene knockouts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000a;1488:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapirstein A, Bonventre JV. Phospholipases A2 in ischemic and toxic brain injury. Neurochem Res. 2000b;25:745–753. doi: 10.1023/a:1007583708713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapirstein A, Saito H, Texel SJ, Samad TA, O'Leary E, Bonventre JV. Cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha regulates induction of brain cyclooxygenase-2 in a mouse model of inflammation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1774–1782. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00815.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Kitagawa K, Yamagata K, Takemiya T, Tanaka S, Omura-Matsuoka E, Sugiura S, Matsumoto M, Hori M. Amelioration of hippocampal neuronal damage after transient forebrain ischemia in cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:107–113. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000100065.36077.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada H, Murakami M, Enomoto A, Shimbara S, Kudo I. Regulation of type V phospholipase A2 expression and function by proinflammatory stimuli. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:826–835. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab JM, Beschorner R, Meyermann R, Gozalan F, Schluesener HJ. Persistent accumulation of cyclooxygenase-1-expressing microglial cells and macrophages and transient upregulation by endothelium in human brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:892–899. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.5.0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KF, Bryant KJ, Bidgood MJ. Functional coupling and differential regulation of the phospholipase A2-cyclooxygenase pathways in inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:535–541. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Yamasaki A, Aze Y, Oida H, Nishimura T, Murata T, Matsuoka T, Ushikubi F, Hirose M, Tanaka T, Yoshida N, Narumiya S, Ichikawa A. Patent ductus arteriosus and neonatal death in prostaglandin receptor EP4-deficient mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:7–12. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama N, Mizuta S, Hori A, Kobayashi S. Prostaglandin E2 facilitates excitatory synaptic transmission in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rats. Neurosci Lett. 1995;188:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11407-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shie FS, Montine KS, Breyer RM, Montine TJ. Microglial EP2 is critical to neurotoxicity from activated cerebral innate immunity. Glia. 2005;52:70–77. doi: 10.1002/glia.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovic B, Bosetti F, Silva AC. Modulatory role of cyclooxygenase-2 in cerebrovascular coupling. Neuroimage. 2006;32:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sublette ME, Russ MJ, Smith GS. Evidence for a role of the arachidonic acid cascade in affective disorders: a review. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:95–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-5618.2003.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi S, Uozumi N, Ishii S, Shimizu Y, Watanabe T, Shimizu T. Mice deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2 are less susceptible to cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2003;86:169–172. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0651-8_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano T, Panesar M, Papillon J, Cybulsky AV. Cyclooxygenases-1 and 2 couple to cytosolic but not group IIA phospholipase A2 in COS-1 cells. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2000;60:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(99)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemiya T, Maehara M, Matsumura K, Yasuda S, Sugiura H, Yamagata K. Prostaglandin E(2) produced by late induced COX-2 stimulates hippocampal neuron loss after seizure in the CA3 region. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teismann P, Tieu K, Choi DK, Wu DC, Naini A, Hunot S, Vila M, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S. Cyclooxygenase-2 is instrumental in Parkinson's disease neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5473–5478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0837397100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toscano CD, Prabhu VV, Langenbach R, Becker KG, Bosetti F. Differential gene expression patterns in cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 deficient mouse brain. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uozumi N, Kume K, Nagase T, Nakatani N, Ishii S, Tashiro F, Komagata Y, Maki K, Ikuta K, Ouchi Y, Miyazaki J, Shimizu T. Role of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in allergic response and parturition. Nature. 1997;390:618–622. doi: 10.1038/37622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushikubi F, Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Murata T, Matsuoka T, Kobayashi T, Hizaki H, Tuboi K, Katsuyama M, Ichikawa A, Tanaka T, Yoshida N, Narumiya S. Impaired febrile response in mice lacking the prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP3. Nature. 1998;395:281–284. doi: 10.1038/26233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uz T, Dimitrijevic N, Tueting P, Manev H. 5-lipoxygenase (5LOX)-deficient mice express reduced anxiety-like behavior. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2002;20:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leyen K, Kim HY, Lee SR, Jin G, Arai K, Lo EH. Baicalein and 12/15-lipoxygenase in the ischemic brain. Stroke. 2006;37:3014–3018. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000249004.25444.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagami T, Nakazato H, Ueda K, Asakura K, Kuroda T, Hata S, Sakaeda T, Sakaguchi G, Itoh N, Hashimoto Y, Hiroshige T, Kambayashi Y. Prostaglandin E2 rescues cortical neurons from amyloid beta protein-induced apoptosis. Brain Res. 2003;959:328–335. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03773-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yermakova AV, Rollins J, Callahan LM, Rogers J, O'Banion MK. Cyclooxygenase-1 in human Alzheimer and control brain: quantitative analysis of expression by microglia and CA3 hippocampal neurons. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:1135–1146. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]