Abstract

Primary cultures of progenitor and immature rat Leydig cells were established from the testes of 21 and 35 day old rats, respectively. The cell population remained homogeneous after 4–6 days in culture as judged by staining for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase but the cells were unable to bind 125I-hCG or to respond to hCG with classical LH receptor (LHR)-mediated responses including cAMP and inositol phosphate accumulation, steroid biosynthesis or the phosphorylation of the extracellular regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2).

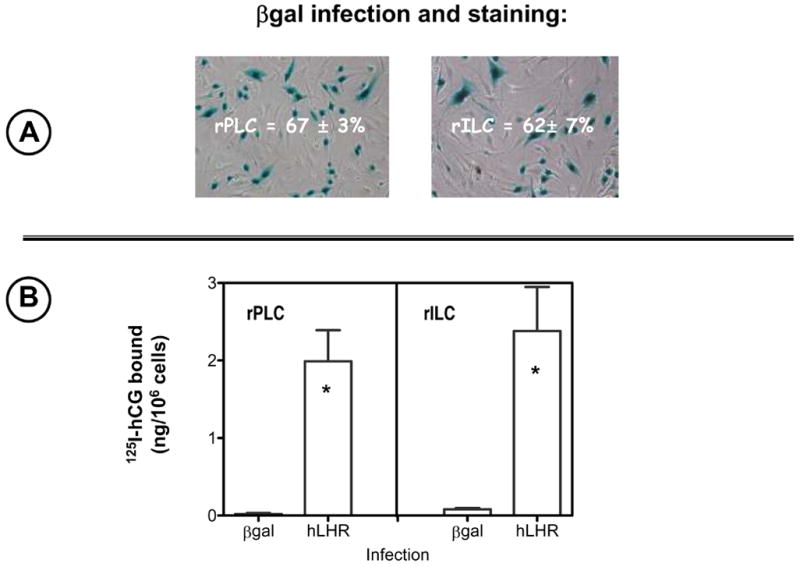

Infection of primary cultures with recombinant adenovirus coding for β-galactosidase showed that ~65% of the cells are infected. Infection with adenovirus coding for the human LHR (hLHR) allowed for expression of the hLHR at a density of ~25,000 receptors/cell and allowed the cells to respond to hCG with increases in cAMP and inositol phosphate accumulation, steroid biosynthesis and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Although progenitor and immature cells were able to respond to hCG with an increase in progesterone, only the immature cells responded with an increase in testosterone.

In addition to these classical LHR-mediated responses the primary cultures of progenitor or immature rat Leydig cells expressing the recombinant hLHR proliferated robustly when incubated with hCG and this proliferative response was sensitive to an inhibitor of ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

These studies establish a novel experimental paradigm that can be used to study the proliferative response of Leydig cells to LH/CG. We conclude that activation of the LHR-provoked Leydig cell proliferation requires activation of the ERK1/2 cascade.

Introduction

Injections of LH/CG were shown to stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of Leydig cells and to induce Leydig cell hyperplasia in rodents many years ago (1–3). The ability of the LHR to stimulate the proliferation of Leydig cells and to behave as a potential Leydig cell oncogene was not generally recognized until recently, however, when the phenotypes of boys harboring naturally occurring mutations of the hLHR gene were described (reviewed in refs. 4–7). 46XY individuals harboring germ line activating mutations of the hLHR have Leydig cell hyperplasia whereas those harboring germ line inactivating mutations of the hLHR have Leydig cell hypoplasia. In addition, the finding of a somatic activating mutation of the hLHR in Leydig cell adenomas of several unrelated boys with precocious puberty (8–10) suggests that the LHR could even be involved in the transformation of Leydig cells. The mitogenic and oncogenic potential of the LHR is also supported by other recent observations made in genetically modified mouse models (reviewed in refs. 11–13). For example, mice lacking GnRH as well as mice with targeted deletion of the LHR exhibit Leydig cell hypoplasia (14–16) whereas transgenic mice overexpressing hCG or LH develop Leydig cell adenomas (13, 17). LH administration can also induce the development of Leydig cell tumors in other transgenic mice models (18, 19) and wild-type mice with high levels of LH induced by administration of 5α-reductase inhibitors (20) display an increased incidence of gonadal tumors. Lastly, when ectopically expressed in the adrenal cortex, the LHR induces gonadotropin-dependent adrenocortical hyperplasia or adrenocortical tumors (21, 22).

These data lead us to postulate that the LHR activates signaling cascades that promote the proliferation and/or survival of Leydig cells.

There is a growing body of recent evidence from many different laboratories that implicate the LHR as a stimulant of mitogenic and/or survival signaling cascades such as the ERK/12 pathway. The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is increased by LH/CG in primary cultures of granulosa cells (23, 24), immortalized granulosa cell lines (25), MA-10 Leydig tumor cells (26, 27) and primary cultures of immature rat Leydig cells (28). Although this signaling pathway is emerging as an important regulator of steroidogenesis in Leydig (28), granulosa (25, 29), and Sertoli cells (30) there are no reports examining its potential involvement as a mediator of the LHR-provoked proliferation of Leydig cells.

Methods to isolate homogenous populations rat Leydig cells of different stages of differentiation and to maintain them in short term primary culture have been previously established by several laboratories (28, 31–33). Although freshly isolated Leydig cells of different stages of differentiation express the LHR (32, 34, 35) and display a variety of acute and classical LHR-mediated responses such as cAMP accumulation, steroidogenesis and ERK1/2 activation (28, 31–33) they are not very useful in the study of proliferation for at least two reasons. Freshly isolated rat Leydig cells loose viability, display a reduced rate of DNA replication and become apoptotic during the first 48 hours following isolation (36) and proliferation assays are best done using cells that have been allowed to become quiescent by serum deprivation (37, 38). Therefore freshly isolated Leydig cells have to be incubated in serum-free medium for 24–48 hours prior to testing the effects of hormones on proliferation (36, 38, 39).

Maintaining primary cultures of Leydig cells for several days would be more useful in the study of Leydig cell proliferation but maintaining gonadotropin responsiveness over a period of days in culture is a more complicated process. Primary cultures or rat Leydig cells maintained for 1–3 days attached to Cytodex® beads and using culture medium supplemented with low levels of partially purified LH alone or together with DHT display LHR-mediated responses such as cAMP and steroidogenesis (32, 34, 35). It is not clear if these conditions are also beneficial to cell proliferation, however. In fact, attempts to demonstrate an effect of LH/CG on DNA replication in short term cultures of rat Leydig cells maintained with or without low levels of LH have not always been successful (38–41).

In this paper we show that progenitor or immature rat Leydig cell expressing the recombinant LHR can be maintained in primary culture for several days and that they proliferate in response to LHR activation. Using these primary cultures and inhibitors of the ERK1/2 cascade we have tested the hypothesis that this signaling pathway is a mediator of the LHR-provoked proliferation of Leydig cells.

Materials and Methods

Isolation, culture and infection of Leydig cells

Progenitor (rPLC) and immature (rILC) Leydig cells were isolated from testes of 21 and 35 day old rats, by Percoll gradient centrifugation (28, 33). Decapsulated testes were incubated with type I collagenase (0.25 mg/ml) for 20 min at 37 C and the digested tissue passed through a 70 μm cell strainer. The filtrate was centrifuged at 250 x g for 8 min at room temperature and the pellet was washed once by centrifugation with Hanks’ balanced salt solution without Ca+2 or Mg+2 (CMF-HBSS) containing 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (CMF-HBSS-BSA). To obtain purified Leydig cells, this crude cell suspension was loaded on top of a discontinuous gradient consisting of layers of 5 ml of 20% Percoll, 10 ml of 40% Percoll, 10 ml of 60% Percoll, and 3 ml of 90% Percoll (all made in CMF-HBSS) and subsequently centrifuged at 800 x g for 20 min at room temperature. The third band of cells from the top was collected, diluted with two volumes of CMF-HBBS-BSA and centrifuged at 350 x g for 10 min at room temperature. The pellet was resuspended in CMF-HBSS-BSA, mixed with 90% Percoll (containing color beads of a density of 1.068 g/ml) to give a final Percoll concentration of 60% and centrifuged at 20,000 x g for 30 min at 4ºC. The Percoll fraction with a density lower than 1.068 g/ml was discarded and the higher density fraction (containing purified Leydig cells) was diluted with 2 volumes of CMF-HBSS-BSA and centrifuged at 350 x g for 10 min at room temperature. The purified Leydig cells were resuspended in culture medium (DMEM/F12) supplemented with 15 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), BSA (1 mg/ml) and gentamicin (100 μg/ml), centrifuged again, resuspended in the same medium (BSA-containing medium) and counted. Cell yields were ~0.3 x106 and ~2 x 106/rat for the 21 and 35-day old rats, respectively. These procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee for the University of Iowa.

Cells were plated in DMEM/F12 with 0.1%BSA in gelatin-coated 12 well plates at a density of 1 x 105 (progenitor) or 2 x 105 (immature) cells/well, in a total volume of 1.0 ml of medium. The cell culture plasticware was coated with gelatin as described before (42). One day after plating the culture medium was changed to DMEM/F12 supplemented with 15 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 2% newborn calf serum and 100 μg/ml gentamicin (serum-containing medium). Two days after plating, some wells were trypsinized (43) and counted and the rest were washed twice with BSA-containing medium and incubated with the recombinant adenovirus coding for the hLHR (Ad-hLHR) or for β-galactosidase (Ad-βgal) used at 200 MOI (multiplicity of infection = number of viable viral particles/cell) for 2 h at 37º C in a total volume of 1 ml (44). At the time of infection (day 2) the number of attached progenitor or immature cells was ~0.5 x 105 cells/well. The infection solution was then aspirated and replaced with serum-containing medium to prevent further infection. The following day (3 days after plating) the medium was changed again to BSA-containing medium and all experiments were initiated 4 days after plating (2 days after infection). On day 4 there were ~1 x 105 cells/well for progenitor and immature cells and the wells were ~40% confluent.

Immunocytochemistry

On day 4, the cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde dissolved in 10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4 (PBS) for 10 minutes at 4ºC. After washing twice with 10 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 (TBS) the cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes at room temperature. The cells were processed with the avidin-biotin complex (ABC) method using the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector, Burlington, CA) according to the manufacturer instructions. The fixed cells were incubated for 60 min at room temperature in a solution of 0.5% goat serum, 0.1% Triton X-100 in TBS. The cells were then incubated overnight at 4ºC with a 1/1000 dilution of a rabbit antiserum to 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) or normal rabbit serum in 0.1% Triton X-100 in TBS. After washing twice with 0.1%Triton X-100 in TBS, the cells were treated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (1/500 dilution) in TBS containing 3% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature. This was followed by a 30 min incubation with 0.6% hydrogen peroxide in TBS. Then, the ABC reagent was applied for 1 hour and the immune complexes were revealed with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen, (prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions), for 10 minute at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 ml of water and the cells were examined and photographed with a phase contrast microscope.

Beta galactosidase staining

On day 4, the cells were washed twice with 10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.4 (PBS) and fixed with 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed again with PBS and stained with a solution of 1 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-inolyl-beta-galactosidase, 5mM potassium ferrocyanide, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, and 2 mM MgCl2 all dissolved in PBS. Following an overnight incubation at 37ºC, the cells were washed twice with PBS. The percent of infected cells was calculated by scoring three hundred cells from each transfection for the presence of a blue precipitate in the cytosol.

Cell counting

On day 4 the medium was replaced and the cells were then incubated with or without hormones (in a total volume of 1 ml of BSA-containing medium). The cells were counted on day 5 and day 6 but the medium and hormones were replaced on day 5 for the cells that were counted on day 6. The cells were trypsinized as described for MA-10 cells (43) and counted in a Coulter® counter.

[3H] Thymidine incorporation

The cells were incubated with or without hormones for 24 hours as described for the cell counting experiments. [3H-methyl]-thymidine (2 μCi/ml) was added during the last 4 h of the incubation. The cells were washed twice with 1 ml of 20 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.4) and then incubated with 0.5 ml of cold 10% trichloroacetic acid for 30 min on ice. After aspiration the cells were washed twice with 0.5 ml of the same solution. The cells were then dissolved in 500 μl of 0.5 N NaOH. mixed with 10 ml of BudgetSolve, neutralized with 125 ml of 2N HCl and counted in a liquid scintillation counter.

Thymidine incorporation in freshly isolated cells was measured in suspendend cells incubated with [3H-methyl]-thymidine (2 μCi/ml) for 4 h. These cells were washed by centrifugation using the buffers described above. After precipitation of the cell pellets with trichloroacetic acid the precipitates were solubilized and counted as described above.

Hormone binding, second messenger, and steroid assays

All of these assays were also done on day 4. Binding assays were done during a one hour incubation at room temperature with 100 ng/ml of 125I-hCG with or without an excess of non-radioactive hCG (to correct for non-specific binding) as described elsewhere (42). Steroids and cAMP were measured using enzymatic immune assays using commercially available kits (Cayman Chemicals, progesterone and testosterone) or by radioimmunoassay (cAMP) using reagents prepared in our own laboratory. For these assays the cells were incubated with or without hCG (100 ng/ml) for 4 hours in the presence of 1 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (to inhibit cAMP phosphodiesterases) as described elsewhere (42). Inositol phosphate accumulation was measured in cells prelabeled with [3H]myo-inositol (42) and incubated with or without hCG (500 ng/ml) for 1 hour in the presence of 20 mM LiCl (to inhibit the degradation of inositol phosphates). The concentrations of hCG used are the minimal concentration of hCG that elicit maximal responses in each of these assays (42).

Western blots

These methods have also been described (27, 42, 45). Primary antibodies to phosphoERK1/2, total ERK1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), P450scc (Chemicon) and 3β-HSD (a generous gift of Dr. Anita Payne) were used at dilutions of 1/5,000, 1/10,000, 1/1,000 and 1/1,000, respectively. Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were used at dilutions of 1/10,000 and 1/3,000, respectively.

Statistical analysis

A two tailed t-test was used for comparing two groups (Figures 2B, 7A and 9), ANOVA with Dunnet’s post test was used for multiple comparisons to a control group (Figures 5 and 6) and ANOVA with Bonferroni post test was used for multiple comparisons among groups (Figures 3, 4, 7B and 8). These analyses were performed using the InStat Software package from Graphpad Software (San Diego, CA). In all cases statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Figure 2. Recombinant proteins can be readily expressed in primary cultures of rat Leydig cells by infection with adenoviral vectors.

Panel A. Two days after infection with Ad-βgal the cells were stained for β-gal activity and examined by phase contrast microscopy as shown. The percent of stained cells was scored as described in Materials and Methods. The micrographs show the results of one representative experiment and the numbers inside them show the percent of infected cells as judged by βgal staining (mean ± SEM of three independent infections).

Panel B. 125I-hCG binding was measured two days after infection with Ad-βgal or Ad-hLHR during a 1 hour incubation at room temperature with 100 ng/ml 125I-hCG as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar shows the mean ± SEM of three independent infections. The asterisk denotes statistical significance (p < 0.05, two tailed t-test) when compared to same cell stage infected with Ad-βgal.

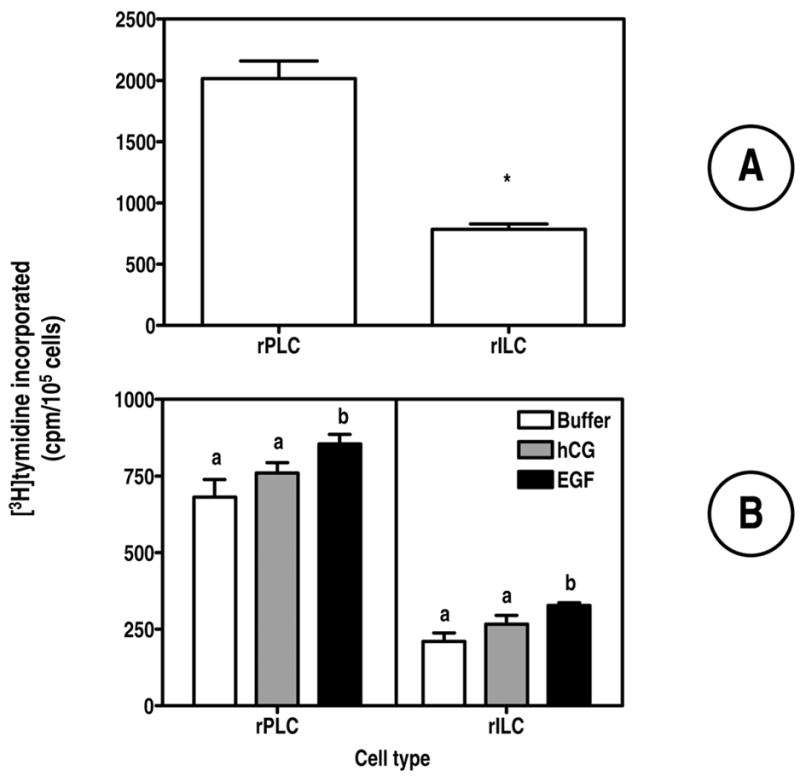

Figure 7. Human CG does no stimulate DNA replication in primary cultures of rat Leydig cells that are not infected with Ad-hLHR.

A One ml of freshly isolated cells containing 1–2 x 105 progenitor or immature cells (kept in suspension) were incubated for 4 h with [3H]-thymidine . Incorporated thymidine was then measured as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of four independent experiments. The asterisk denotes statistical significance (p < 0.05, paired t-test) between the two cell stages.

B Freshly isolated rPLC or rILC (1–2 x 105) were plated on 12 wells plates as described in Materials and Methods. Twenty four hours after plating the medium was changed and the cells were incubated in one ml of serum-free medium containing buffer only, hCG or EGF (each at 100 ng/ml) as indicated. Twenty hours later [3H]-thymidine was added and the incubation was continued for 4 hours. Incorporated thymidine was then measured as described in Materials and Methods. Parallel cultures were used to determine cell density at the beginning and at the end of the 24 incubation with buffer or hormones. The number of attached cells varied from 0.7 to 1.8 x 105/well but it did not change from the beginning to the end of the 24 incubation. The number of cells was also the same in the cultures incubated with buffer only, hCG or EGF. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. Within a panel, the bars with different letters (a, b) are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni post test).

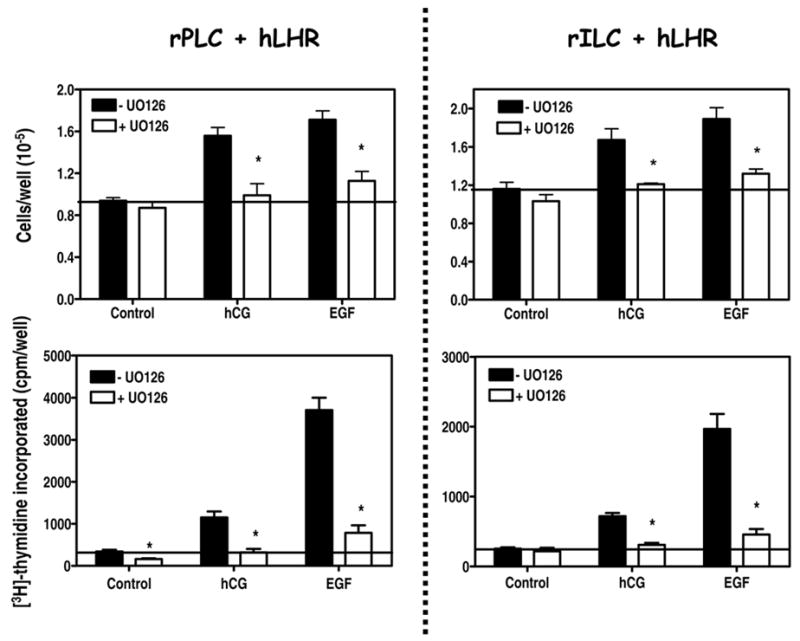

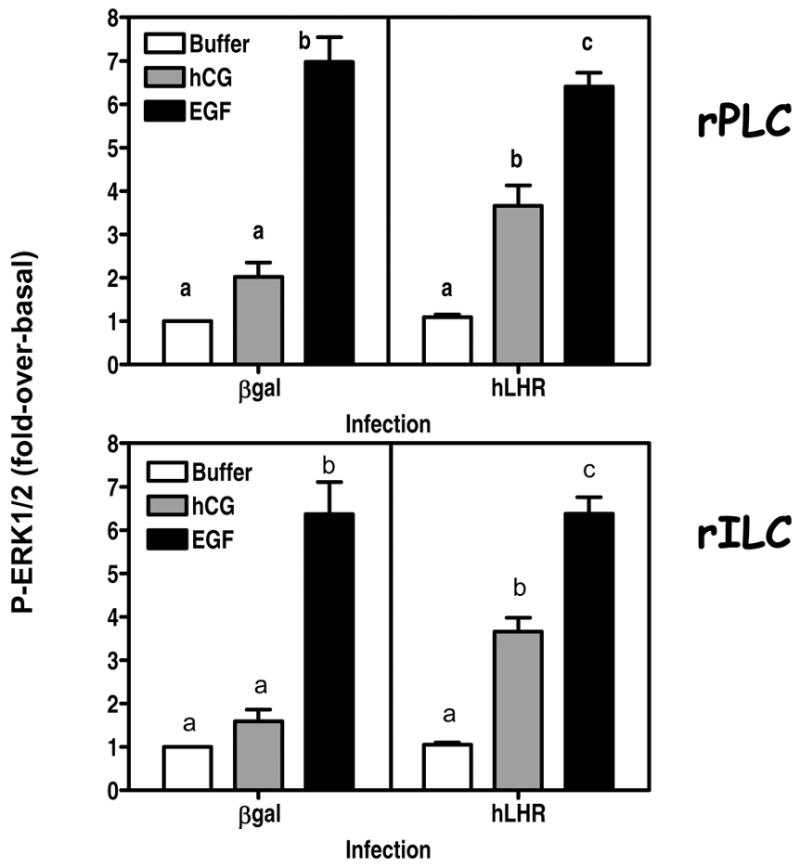

Figure 9. UO126 inhibits the proliferative effects of hCG and EGF on primary cultures of rat Leydig cells.

The cells were infected on day 2 with 200 MOI Ad-hLHR.

Top panels. On day 4 subconfluent wells were cultured in serum free medium without or with 10 μM UO126 containing buffer only, hCG (100 ng/ml) or EGF (100 ng/ml) as indicated. The medium, inhibitor and hormones were replaced on day 5. The plates were trypsinized and the number of cells was determined on day 6 as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of 6 independent experiments. For a given pair the asterisks denote significant differences (p < 0.05, two tailed t-test) when compared to cells incubated without UO126. The horizontal line is drawn at a value of 1. This value marks the number of cells present at the beginning of the experiment (day 4).

Bottom panels. On day 4 subconfluent wells were cultured in serum free medium without or with 10 μM UO126 containing buffer only, hCG (100 ng/ml) or EGF (100 ng/ml) as indicated. The cells were labeled with [3H]-thymidine during the last 4 hours of a 24 incubation and the radioactivity incorporated into DNA was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of 6 independent experiments. For a given pair the asterisks denote significant differences (p < 0.05, two tailed t-test) when compared to cells incubated without UO126. The horizontal line is drawn at the level of [3H]-thymidine incorporated into control cells incubated without UO126. Note the different vertical scales in the left and right panels.

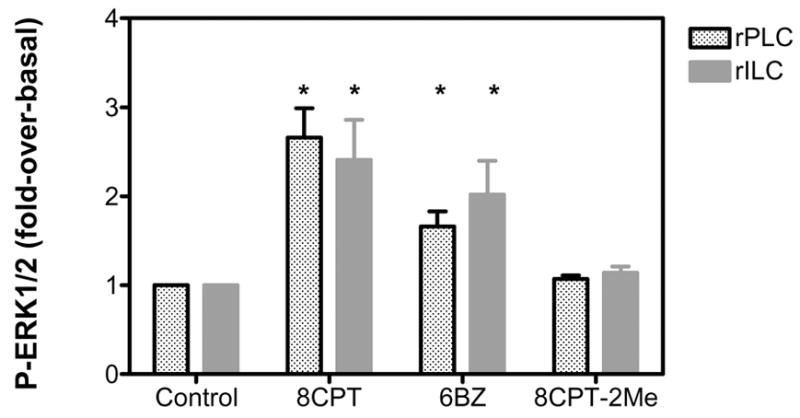

Figure 5. A PKA-selective cAMP analog stimulates ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary cultures of rat Leydig cells.

The cells were infected on day 2 with 200 MOI Ad-hLHR. The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was measured on day 4 in cells incubated with buffer only, 0.5 mM 8CPT-cAMP (8CPT), 6-Benzoyl-cAMP (6BZ) or 8CPT-2-Methyl cAMP (8CPT-2Me) for 15 min as indicated and as described in Materials and Methods.

The results are presented as fold-over-basal and each bar is the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The asterisks denote significant differences (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Dunnet’s post test) when compared to same stage cells incubated with buffer only (control).

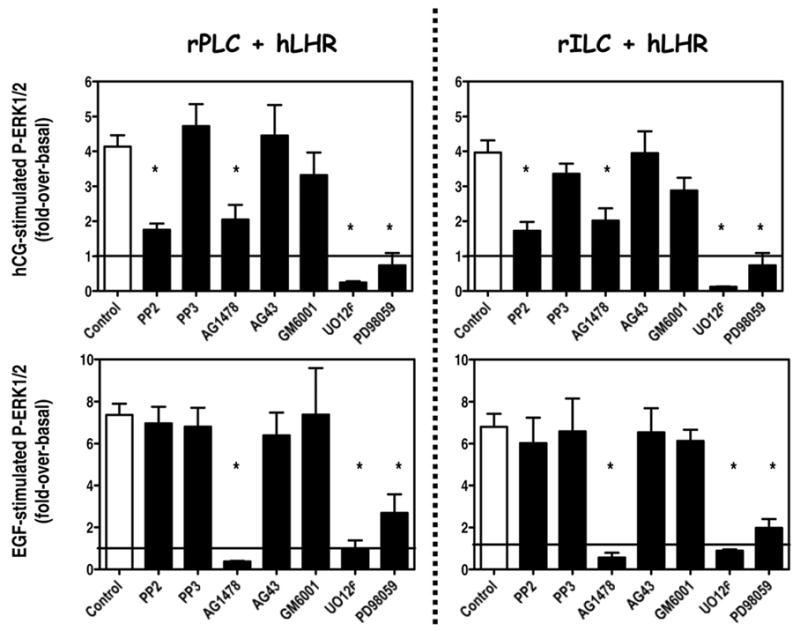

Figure 6. Effects of several inhibitors on the hCG- or EGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary cultures of rat Leydig cells.

The cells were infected on day 2 with 200 MOI Ad-hLHR. On day 4 the cells were preincubated for 30 min with PP2 or PP3 (10 μM), AG1478 or AG43 (1 μM), GM6001 (2 μM), UO126 (10 μM) or PD98059 (100 μM) as indicated. The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was then measured at the end of a 15 min incubation with 100 ng/ml hCG (top panels) or a 5 min incubation with 100 ng/ml EGF (bottom panels).

The results are presented as fold-over-basal and each bar is the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The asterisks denote significant differences (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Dunnet’s post test) when compared to same stage cells incubated with buffer only (control). The horizontal line is drawn at a value of 1, which is the basal level of ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

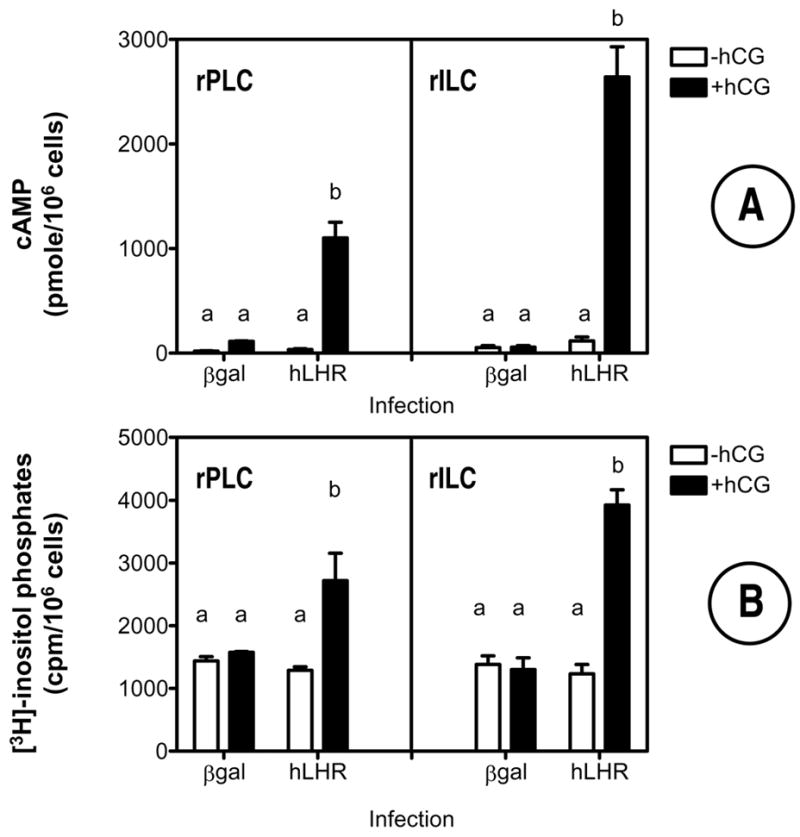

Figure 3. Expression of the hLHR allows hCG to stimulate cAMP, inositol phosphate and steroid accumulation in primary cultures of rat Leydig cells.

The cells were infected on day 2 with Ad-βgal or Ad-hLHR (200 MOI) as indicated. All assays were performed on day 4 in cells incubated without or with 500 ng/ml hCG for 1 hour (inositol phosphates, panel B) or with 100 ng/ml hCG for 4 hours (cAMP and steroid assays, panels A, C and D) as described in Materials and Methods.

Each bar is the mean ± SEM of 3–5 independent experiments. Means within a panel with different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni post test).

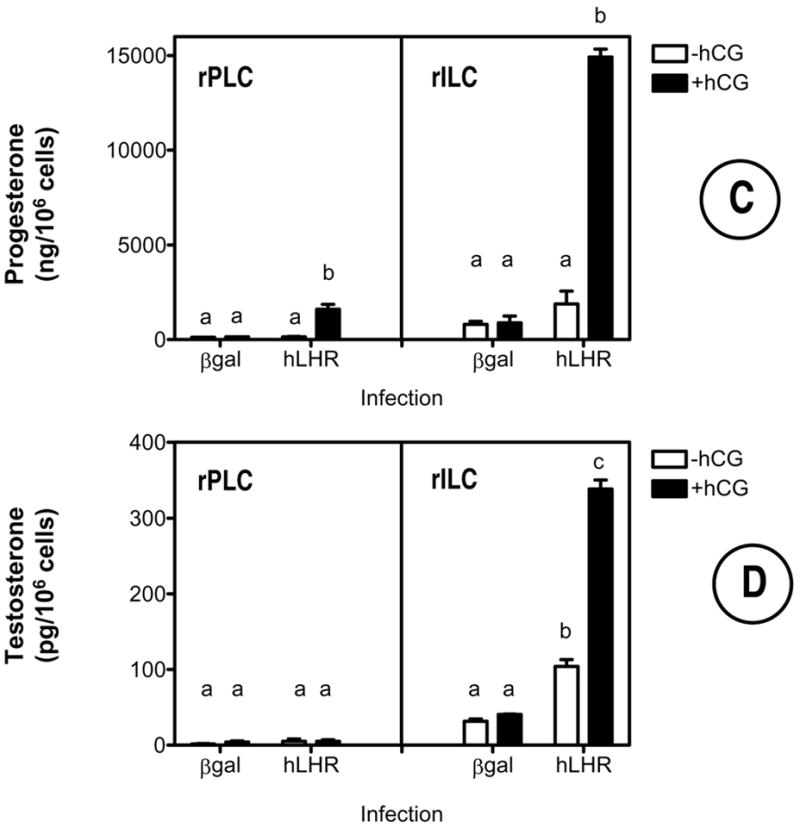

Figure 4. Expression of the hLHR allows hCG to stimulate ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary cultures of rat Leydig cells.

The cells were infected on day 2 with Ad-βgal or Ad-hLHR (200 MOI) as indicated. The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was measured on day 4 in cells incubated with buffer only, 100 ng/ml hCG (x 15 min) or 100 ng/ml EGF (x 5 min) as indicated and as described in Materials and Methods.

The results are presented as fold-over-basal and each bar is the mean ± SEM of 4–7 independent experiments. Means within a panel with different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni post test).

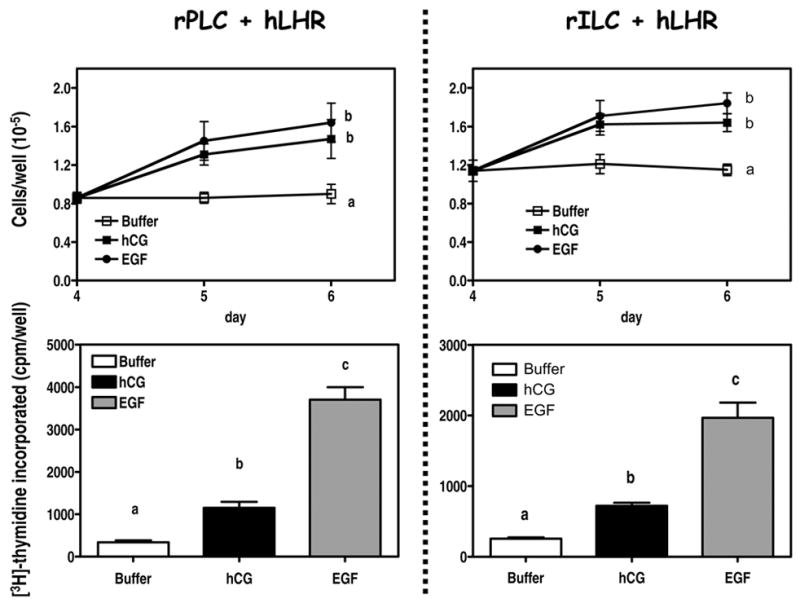

Figure 8. Human CG and EGF stimulate the proliferation of primary cultures of rat Leydig cells.

The cells were infected on day 2 with 200 MOI Ad-hLHR.

Top panels. On day 4 subconfluent wells were cultured in serum free medium containing buffer only, hCG (100 ng/ml) or EGF (100 ng/ml) as indicated. The medium and hormones were replaced on day 5. The plates were trypsinized and the number of cells was determined on days 4, 5 and 6 as described in Materials and Methods. Each point is the mean ± SEM of 6 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out only for the data obtained on day 6. Within a panel, the day 6 points with different letters (a, b) are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni post test).

Bottom panels. On day 4 subconfluent wells were cultured in serum free medium containing buffer only, hCG (100 ng/ml) or EGF (100 ng/ml) as indicated. The cells were labeled with [3H]-thymidine during the last 4 hours of a 24 incubation and the radioactivity incorporated into DNA was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of 6 independent experiments. Within a panel, the values of the bars marked by the different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni post test). Note the different vertical scales in the left and right panels.

Hormones and supplies

Purified hCG (CR-127) was purchased from Dr. A. Parlow of the National Hormone and Pituitary Agency (Torrance, CA). Purified recombinant hCG was kindly provided by Ares Serono (Randolph, MA). AG1478, AG43, PP2, PP3, GM6001, H89, PD98059, 8-CPT-cAMP, N6-benzoyl-cAMP, and 8-CPT-2Me cAMP were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). UO126 was from Tocris (Ellisville, MO). Cell culture medium was obtained from Invitrogen Corp. and cell culture plasticware was from Corning. [3H-methyl]-thymidine (20 Ci/mmol) and [3H]myo-inositol (10 Ci/mmol) were from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA). All other chemicals were obtained from commonly used suppliers.

Results

Establishment and characterization of primary cultures of rat Leydig cells

We reasoned that establishing long term primary cultures of Leydig cells that maintain gonadotropin responsiveness in the absence of gonadotropins would be a desirable goal to study the proliferative response of Leydig cells to LH/CG. To address these issues we attempted to establish primary cultures of Leydig cells from 21 and 35 day old rats that could be maintained for at least 6 days. Animals of these two ages were chosen because there is agreement that the testes of 21 day old rats contain mostly rPLC whereas those of 35 day old rats contain mostly rILC and that these two populations of Leydig cells have the capacity to proliferate (46, 47). The 6 day culture period was arbitrarily chosen because it was considered long enough to examine the proliferative potential and responsiveness of the primary cultures.

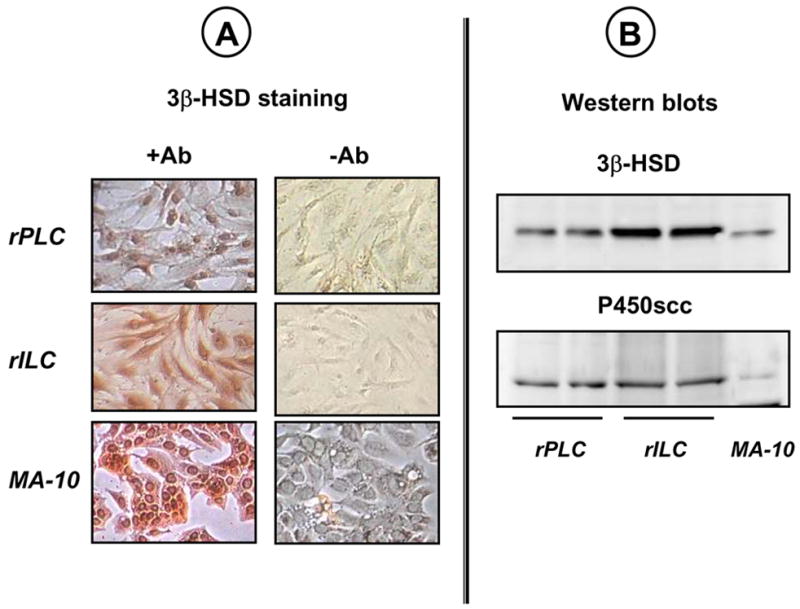

Figure 1A shows that after 4 days our primary cultures contain mostly (or entirely) Leydig cells as judged by staining for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. As expected, the level of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase is higher in immature than in the progenitor cells (34, 46, 47). The expression of a second Leydig cell marker (the cholesterol side chain cleavage enzyme, P450scc) can also be readily detected on Western blots as shown in Figure 1B. The level of this enzyme was the same in both cell stages, however.

Figure 1. Primary cultures of progenitor (rPLC) and immature (rILC) rat Leydig cells express markers of Leydig cell lineage.

Rat Leydig cells were isolated from 21-(rPLC) or 35-(rILC) day old rats and maintained in primary culture as described in Material and Methods. MA-10 cells were cultured as described elsewhere (42, 43) and were used as positive controls.

Panel A. Four-day old cultures were stained with (+Ab) or without (-Ab) an antibody for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD). The results of a representative experiment are shown.

Panel B. Western blots of whole cell lysates from two different 4-day old cultures were probed with antibodies to 3β-HSD or P450scc as shown. Only the relevant portions of the blots of a representative experiment are shown.

After 4 days these primary cultures do not retain significant levels of endogenous LHR as judged by 125I-hCG binding (Figure 2B) and their LHR-mediated responses are weak or absent (Figure 3). In an attempt to restore 125I-hCG binding and hCG responsiveness we infected the primary cultures with adenoviral vectors coding for β-galactosidase (Ad-βgal) or the hLHR-wt (Ad-hLHR) and tested for expression of the encoded proteins by enzymatic activity (β-galactosidase) or by 125I-hCG binding (hLHR). The results presented in Fig 2A show that when the primary cultures are infected with

Ad-βgal at a multiplicity of infection of 200 (MOI, the number of viable viral particles added per Leydig cell) about 65% of the Leydig cells stain for β–galactosidase activity. When infected with Ad-hLHR at a MOI of 200 the primary cultures bind ~2 ng 125I-hCG/106 cells. Lowering the MOI to 20 resulted in little or no infection and increasing it to 500 increased the percent of infected cells (measured by staining for β-galactosidase activity) to ~70% and the binding of 125I-hCG to ~6 ng/106 cells (data not shown). All experiments shown herein were done with cells infected with Ad-hLHR at an MOI of 200.

Although the hLHR construct subcloned into the adenoviral vector is tagged with the myc epitope (see ref. 44) we cannot detect its expression by fluorescent microscopy using anti-myc antibodies1. This is likely due to the relatively low level of expression of the receptor. In our experience, this method allows for detection of receptor expression in transiently transfected cells only at levels of 125I-hCG binding that are 3-5 times higher than that shown in Figure 2B (42). Thus we do not really know what percentage of the cells infected with the Ad-hLHR express the recombinant hLHR. We can only approximate this number to ~65% based on the data obtained with the Ad-βgal infected cells (Figure 2A).

In agreement with the lack of 125I-hCG binding in the cells that were not infected with the Ad-hLHR, classical hCG responses such as cAMP synthesis, inositol phosphate accumulation and steroid synthesis were either undetectable or barely detectable in the cells infected with Ad-βgal (Figure 3). In contrast, addition of hCG to Ad-hLHR-infected cells robustly stimulated cAMP (Figure 3A), inositol phosphates (Figure 3B) and steroid accumulation (Figures 3C and 3D). The steroid responses shown in Figures 3C and D are interesting because they show that progenitor rat Leydig cells infected with the Ad-hLHR respond to hCG with an increase in progesterone synthesis whereas immature rat Leydig cells respond with an increase in both, progesterone and testosterone synthesis. The levels of progesterone detected in the immature cells are much higher than the levels of testosterone, however (compare the scales in Figures 3C and D). We did not examine the reasons for the lack of a testosterone response in the progenitor rat Leydig cells but others have shown that 20–40 days postpartum the maturing Leydig cells produce mostly 5α-reduced androgens rather than testosterone (reviewed in ref. 46). We also note that the increased levels of testosterone in the immature cells are in agreement with the higher expression of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in this cell stage (Figure 1B).

Lastly, although not always obvious from the data presented in Figure 3, the basal levels of cAMP, progesterone and testosterone tended to be higher in Ad-hLHR infected than in Ad-βgal infected cells. This trend attained statistical significance only for testosterone synthesis in the immature cells (Figure 3D).

Activation of the LHR stimulates ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary cultures of progenitor and immature rat Leydig cells

Since we wanted to determine if the ERK1/2 cascade is involved in the proliferative response of Leydig cells we also examined the ability of hCG to increase the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in these primary cultures. Figure 4 shows that Ad-βgal infected rPLC or rILC do not respond to hCG with a significant increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Infection with Ad-hLHR did not affect basal phosphorylation of ERK1/2 but it conferred robust hCG responsiveness to both cell stages. Figure 4 also shows that the ERK1/2 pathway of both cell stages is sensitive to EGF stimulation regardless of the expression of the hLHR. EGF was used as a positive control in this and subsequent experiments because activation of the EGFR stimulates the ERK1/2 cascade in MA-10 cells (26, 27) and DNA synthesis in primary cultures of rat Leydig cells (38, 40, 41). Moreover EGF is a potent mitogen for many cell types (48).

When consider together the data summarized in Figures 3 and 4 show that 4 day-old primary cultures of Leydig cells do not retain robust responsiveness to hCG unless they are infected with Ad-hLHR. We note, however, that there may be some residual hCG-induced responses in progenitor and immature cells that were not infected with Ad-hLHR. Human CG-induced cAMP responses in rPLC infected with Ad-βgal (left panel of Figure 3A) and the hCG-induced ERK1/2 responses of rPLC and rILC infected with Ad-βgal (left panels of Figure 4) appeared higher than those of cells incubated without hCG but did not attain statistical significance. The reason why only some responses are measurable is not known, but it could simply be due to the presence of a small amount of endogenous receptors and the sensitivity of the different assays used. Moreover even when these responses were present they were clearly enhanced by infection with Ad-hLHR (Figures 3 and 4).

The ability of hCG to enhance ERK1/2 phosphorylation in Leydig cells has been previously studied using freshly isolated immature rat Leydig cells or MA-10 cells (26–28). This pathway appears to require the participation of PKA, Fyn, the EGFR and Ras. Some of these conclusions were confirmed by the experiments presented in Figures 5 and 62. Figure 5 shows that ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary cultures of rPLC or rILC Leydig can be stimulated with 8-CPT-cAMP, a cAMP analog that does not discriminate between PKA and the Epacs or with N6-Benzoyl-cAMP which is selective for PKA, but it cannot be stimulated with 8-CPT-2Me cAMP, which is Epac-selective (49–51). In agreement with the data obtained in MA-10 cells (27), the results presented in Figure 6 (top panels) show that the hCG-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in primary cultures of progenitor or immature rat Leydig cells infected with the Ad-hLHR can be partially blocked with an inhibitor of the Src-family of kinases (PP2) or an inhibitor of the EGFR kinase (AG1478). The inactive analogs of these compounds (PP3 and AG43, respectively) have no effect. These data also show that UO126 and PD98059, two inhibitors of MEK (the kinase that phosphorylates ERK1/2) completely block the ability of hCG to stimulate ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Lastly, GM6001, a broad metalloprotease inhibitor that blocks the proteolysis of some of the EGF-like growth factor precursors (52) has no effect on hCG-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The same inhibitors were tested on the EGF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation and the results (bottom panels of Figure 6) are in complete agreement with those previously reported using MA-10 cells as well (27). The EGF-provoked ERK1/2 response is inhibited only by the inhibitor of the EGFR kinase (AG1478) and by the two MEK inhibitors (UO126 and PD98059).

Human CG and EGF are mitogens for primary cultures of progenitor and immature rat Leydig cells

In order to determine if activation of the LHR promotes the proliferation of Leydig cells we first attempted to examine this issue by measuring [3H]-thymidine incorporation in freshly isolated rPLC or rILC as described by others (36, 38–41).

In agreement with previous results (39) we found that freshly isolated rPLC have a higher basal level of DNA synthesis than freshly isolated rILC (Figure 7A) and that there is a spontaneous decrease in basal levels of DNA synthesis (36) as the cells are maintained in culture for 2 days (compare the empty columns for each cell type in Figures 7A and 7B). Others have previously examined the effects of hCG or growth factors such as EGF or IGF1 on [3H]-thymidine incorporation in freshly isolated rPLC or rILC (that have been allowed to become quiescent by serum deprivation for 24 hours) with mixed success. The growth factors always significantly stimulate thymidine incorporation in these cultures but the effects of hCG are not always significant (38–41).

Using uninfected rPLC or rILC we found that hCG did not stimulate [3H]-thymidine incorporation (Figure 7B). Under the same conditions EGF had a small stimulatory effect, however (Figure 7B). It should also be noted that the effect of EGF, although statistically significant, was of small magnitude. Lastly, neither hCG nor EGF increased the number of cells attached to the wells. These findings agree with the lack of many other LHR-mediated responses in primary cultures of non-infected rPLC or rILC (Figures 3 and 4).

Since the culture conditions used above cannot be used to study the possible effects of hCG on Leydig cell proliferation we next tried Ad-hLHR infected cells. Subconfluent cultures of Ad-hLHR-infected rPLC or rILC were incubated with buffer only, hCG or EGF. The number of attached cells were measured after 24 or 48 hours (top panels of Figure 8) and the rates of DNA synthesis were measured using a [3H]-thymidine pulse given during the last four hours of the initial 24 hour incubation (bottom panels of Figure 8). When incubated in the absence of hormones subconfluent cultures of Ad-hLHR-infected cells maintained a constant cell density for 2 days. A 2-day incubation with hCG or EGF increased the density of rPLC 1.9- and 2.1-fold, respectively. Human CG or EGF also increased the density of rILC 1.4- and 1.6-fold, respectively (top panels of Figure 8). Most or all of the increase in cell density provoked by hCG or EGF occurred during the first day of addition of the hormones. This is likely due to the inability of the primary cultures to continue to proliferate rather than to a limitation imposed by contact inhibition. Cultures containing half as many cells as those used for the experiment shown in Figure 8 also failed to increase in density when the incubation with hCG and EGF was continued beyond 2 days.

To ensure that hCG and EGF were stimulating the proliferation of Leydig cells rather than a contaminating cell population we stained the primary cultures for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase before and after a 2 day incubation with hCG or EGF. The results of these experiments showed that, at the end of the 2 day incubation with hCG or EGF the percentage of cells staining positively for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (i.e., >95%, see Fig 1A) was similar to that detected on day 4 before the hormones were added (data not shown).

Addition of hCG or EGF significantly increased [3H]-thymidine incorporation in both cell types (bottom panels of Figure 7) but the magnitude of these effects was somewhat higher in rPLC (3.4- and 10.9-fold for hCG and EGF, respectively) than in rILC (2.8- and 7.7-fold for hCG and EGF, respectively).

Whereas the stimulatory effects of hCG and EGF on cell density were not statistically different (top panels of Figure 9), EGF was more effective than hCG in stimulating thymidine incorporation (bottom panels of Figure 8). This could be due to differences in the sensitivity of the assays, or to the stimulation of opposing pathways. For example, hCG could be stimulating only DNA synthesis whereas EGF could be stimulating DNA synthesis and apoptosis. Thus, in the case of EGF a higher rate of cell multiplication could be balanced by a higher rate of cell death. Although the reasons for these differences remain unresolved, both assays show that hCG and EGF are mitogenic stimuli for Leydig cells of these two stages of differentiation.

Lastly, it should be noted that although basal levels of DNA synthesis decline as the cells are maintained in culture, the basal level of DNA synthesis is always higher in rPLC than in rILC. [3H]thymidine incorporation levels in freshly isolated, two day old uninfected, and 5-day old Ad-hLHR infected rPLC were 2016 ± 141, 681 ± 56 and 430 ± 59 cpm/105 cells, respectively. The corresponding values for rILC were 784 ± 45, 263 ± 35 and 212 ± 16.

The ERK1/2 cascade is involved in the LHR-promoted proliferation of rPLC and rILC

To determine if the ERK1/2 cascade is a mediator of the effects of hCG on Leydig cell proliferation we decided to test the effects of two MEK inhibitors (UO126 and PD98059) and one inhibitor of the Src familiy of kinases (PP2) on the ability of hCG to stimulate the multiplication of rPLC or rILC. These inhibitors were chosen based on the data presented in Figure 6 showing that U0126 and PD98059 inhibit the hCG- or EGF-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation whereas PP2 inhibits only the hCG-mediated response (Figure 6).

Since the ERK1/2 phosphorylation assays are done with a time frame of several minutes and cell proliferation assays are done over a period of 24–48 hours (Figures 7–8) we first incubated the primary cultures or rPLC or rILC with each of these compounds (at the concentrations known to inhibit ERK1/2 phosphorylation, see Figure 6) for 2 days and examined them by microscopy to determine if there were overt signs of toxicity. After a 2-day incubation with UO126, immature rat Leydig cells had a normal morphology whereas those incubated with PD98059 or PP2 showed distinct signs of toxicity such as cell rounding, detachment and other overt changes in cell morphology and (data not shown).

Based on these observations we decided to use only UO126 to determine if the ERK1/2 cascade is involved in the proliferative response of Leydig cell to EGF or hCG. We incubated the cells with or without UO126 and stimulated them with hCG or EGF. The number of cells was determined after a 48 hour incubation and DNA replication was measured during the last four hours of a 24 hour incubation. The results of these experiments (Figure 9) clearly show that UO126 is an effective inhibitor of the hCG- or EGF-induced proliferation of Leydig cells.

Two additional indexes of cell multiplication, increased expression of cyclin D3 and quantitation of viable cells by measuring mitochondrial function also revealed that EGF and hCG stimulate cell multiplication through an ERK1/2 dependent pathway (data not shown).

Discussion

The studies summarized here were designed to establish a Leydig cell culture model that could be used to study the effects of LH/CG on the proliferation of Leydig cells and the signaling pathways that participate in this process. Since rPLC and rILC found in the postnatal testis have the capacity to proliferate (46, 47) we focused our attention on these two cell populations. In agreement with the results of others (28, 31–33), we were able to prepare primary cultures of homogenous populations or rat Leydig cells of these two different stages of differentiation. After 4 days in culture, however, these cells do not bind 125I-hCG or respond robustly to hCG with any of the classical hCG-induced responses (such as cAMP, inositol phosphate and steroid synthesis) unless they are first infected with an adenovirus coding for the hLHR. After one day in culture uninfected cells also failed to respond to hCG with an increase in DNA synthesis. At first glance these findings seem different than those of others who have been able to maintain steroidogenic responses in primary cultures of rPLC or adult rat Leydig cells attached to Cytodex® beads for 3 days (32, 34, 35). This has been accomplished, however, only under chronic hormonal stimulation because these cultures were maintained in medium supplemented with low levels of partially purified LH either alone or together with DHT form the beginning of the culture period (32, 34, 35). The conditions used here are different in that our primary cultures of Leydig cells are maintained attached to gelatin-covered cell culture plasticware and in the absence of LH or DHT. We do not consider this lack of responsiveness a hindrance because Leydig cells can be readily infected using adenoviral vectors and thus, responsiveness to hCG can be restored by infection with an adenovirus coding for the hLHR. Under the conditions chosen here about 65% of the cells can be infected and the level of 125I-hCG binding attained corresponds to ~25,000 LHR/cell (assuming that all cells express the hLHR) or ~38,000 LHR/cell (assuming that only 65% of the cells express the hLHR). This LHR density is similar to that of the endogenous LHR expressed in freshly isolated immature or adult rat Leydig cells which have been reported to express ~9,000 and 20-40,000 receptors/cell (32, 34). The LHR density in freshly isolated progenitor rat Leydig cells is only ~ 2,500 receptor/cell, however (34).

As already mentioned (see Results) we can, to some extent, modulate the density of hLHR expressed in these cultures by changing the amount of virus used for infections. Here we chose to use a single receptor density because we already know from doing these types of experiments with MA-10 cells that increasing the density of the hLHR expressed increases the magnitude of the hCG-induced responses and their sensitivity to hCG (42). Increasing the density of the hLHR expressed in MA-10 cells also increases the basal levels of second messengers and steroid synthesis. This is due to the presence of an intrinsic (agonist-independent) activity of G protein-coupled receptors in general (53) and the hLHR in particular (6, 42). A similar trend was apparent in the primary cultures but this trend attained statistical significance only on basal levels of testosterone in the immature cells. This difference is likely due to the lower density of recombinant hLHR expressed in the primary cultures (~25,000/cell, see above) than in MA-10 cells (~100,000/cell, see ref. 42).

We choose to express the hLHR instead of the rLHR because the expression of the recombinant hLHR is better than that of the recombinant rLHR (6). In fact, although expression of the recombinant rodent LHR can be readily detected in heterologous cell types that robustly express recombinant proteins (such as 293 or COS-7 cells, see ref. 6) we have not been able to detect expression of the rodent LHR by transfection of target cells such as MA-10 cells. In addition a large number of studies conducted by many different investigators have shown that, when expressed in heterologous cell types, the recombinant rodent and human LHR activate the same second messenger pathways such as cAMP and inositol phosphate accumulation (reviewed in ref. 6) and a detailed study from our laboratory show that expression of increasing amounts of the hLHR in MA-10 cells (a mouse Leydig cell line that expresses a low level of endogenous LHR) simply enhances the magnitude and increases the sensitivity of these cells to hCG-induced responses (such as cAMP accumulation, steroidogenesis and ERK1/2 activation) that are also provoked by the endogenous LHR (42). Lastly, there are a large number of activating and inactivating mutants of the hLHR associated with Leydig cell hyperplasia, Leydig cell adenomas, or Leydig cell hypoplasia (reviewed in refs. 6, 7) that could be used in future experiments designed to determine their effects on these cultures.

Because of our interest in Leydig cell proliferation we explored the hCG-induced ERK1/2 response in some detail. We have previously shown that hCG-induces ERK1/2 phosphorylation in MA-10 cells by a pathway that requires PKA, Fyn, EGFR and Ras activation (26, 27) but, because they are transformed, MA-10 cells are not a good model to study the proliferative effects of hCG and the pathways that mediate these effects. Others have also documented an hCG-induced and PKA-dependent ERK1/2 response in freshly isolated immature rat Leydig cells but the potential involvement of this pathway on Leydig cell proliferation was not investigated (28). In agreement with these previously published data, the results presented here show that hCG and a PKA-selective cAMP analog provoke the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in progenitor and immature Leydig cells and that the effects of hCG are sensitive to inhibitors of MEK, the Src family of kinases or the EGFR kinase. Likewise, in agreement with the data obtained with MA-10 cells (27), we show that the effect of hCG on ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the immature or progenitor rat Leydig cells is not sensitive to a metalloprotease inhibitor.

In our view the most interesting findings reported here are (a) that primary cultures of progenitor or immature rat Leydig cells expressing the hLHR proliferate in response to hCG stimulation; and (b) that this response is sensitive to an inhibitor of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The proliferative response to hCG is rather robust. Counting cells and staining the cultures for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (an index of the homogeneity of the cell population) shows that the number of progenitor or immature rat Leydig cells almost doubles during a 24–48 hour incubation period in response to hCG. Remarkably this hCG-provoked increase in cell density is similar to the increase in cell density elicited by EGF, a potent and well-characterized mitogen for many cell types. We do not yet know if hCG is a direct mitogen for Leydig cells or if it induces their proliferation by activating an autocrine/paracrine loop involving stimulation of the synthesis and/or release of growth factors such as IGF-1 (36, 54) or members of the EGF family (55, 56).

In agreement with the results of others (39) we find that DNA synthesis is higher in freshly isolated rPLC than freshly isolated rILC and that the basal level of DNA synthesis declines as cells are placed in culture (36). Interestingly, however, even after five days in culture the relative rate of DNA synthesis under basal conditions is higher in the progenitor cells. This is an important finding that mimics the proliferative properties of these two cell stages in the whole animal (46, 47). After 4 days in culture hCG stimulated DNA synthesis 3- to 4-fold whereas EGF stimulated DNA synthesis 8–10 fold in the Ad-hLHR infected rPLC or rILC. The finding that the proliferative effects of EGF and hCG, measured by cell counting or by [3H]-thymidine incorporation are sensitive to a MEK inhibitor show that the ERK1/2 cascade is a mediator of the proliferative response of Leydig cells. The ERK1/2 cascade is, of course, a prominent mitogenic cascade (57, 58) which is known to be sensitive to LHR activation in Leydig cells (26–28). Up until now, however, the ERK1/2 pathway has been implicated only in the regulation of steroidogenesis in Leydig cells (28, 59). Its potential involvement in Leydig cell multiplication has not been examined.

Although there is abundant evidence for a role of LH/CG and the LHR in the proliferation and differentiation of Leydig cells (see Introduction) the molecular basis of the proliferative effects of LH/CG on Leydig cells are not understood. A common whole animal model used to study Leydig cell proliferation is the regeneration of rat Leydig cells that occurs following their selective destruction with ethane dimethane sulfonate (60). Studies using this model have indeed shown that after EDS ablation, the process of Leydig cell regeneration is regulated by LH (61, 62) but the mechanisms by which LH promotes Leydig cell regeneration have not been studied. Although we are not aware of any reports where the effects of LH/CG on the proliferation of primary cultures of Leydig cells have been examined, there are a number of reports on the effects of LH/CG on DNA replication in these cultures. The effects of LH/CG on [3H]-thymidine incorporation in cultures of rILC or rPLC maintained for 24 hours in the absence of LH are weak and not always significant (38–41). Moreover, maintaining the primary cultures of rPLC or rILC with a low level of partially purified LH for 48 hours (conditions that are known to maintain steroidogenesis, see refs. 32, 34, 35) was shown to induce a small increase in [3H]-thymidine incorporation but had no effect on the subsequent response to a higher concentration of LH/CG (38, 41).

The studies presented here with primary cultures expressing the recombinant hLHR serve to establish a novel experimental paradigm where the effects of LHR activation on Leydig cell proliferation and DNA replication can be readily studied in cell culture. We suggest that the immature rat Leydig cells (instead of the progenitors rat Leydig cells) are the best model to study the proliferative response of Leydig cells to LH/CG for four reasons: (1) the Leydig cell lineage of this cell stage can be more clearly discerned as indicated by their testosterone response to hCG stimulation; (2) the density of recombinant hLHR expressed in these cells is similar to that measured in freshly isolated cells; (3) their proliferative response to hCG is only slightly lower than that of progenitor rat Leydig cells; and (4) they are isolated from the postnatal period that corresponds to development of the adult generation of Leydig cells when the levels of LH and testoterone are both rising (63).

Lastly, although our studies were restricted to expression of the recombinant wild-type hLHR, our data show that adenoviral vectors can be readily used to express recombinant proteins in primary cultures of rat Leydig cells. This method should thus be useful in the study of the actions of naturally occurring mutants of the hLHR or any other aspect of the biology of Leydig cells that is facilitated by the expression of recombinant proteins.

Footnotes

Supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA-40629).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: THE AUTHORS HAVE NOTHING TO DECLARE

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an un-copyedited author manuscript copyrighted by The Endocrine Society. This may not be duplicated or reproduced, other than for personal use or within the rule of “Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials” (section 107, Title 17, U.S. Code) without permission of the copyright owner, The Endocrine Society. From the time of acceptance following peer review, the full text of this manuscript is made freely available by The Endocrine Society at http://www.endojournals.org/. The final copy edited article can be found at http://www.endojournals.org/. The Endocrine Society disclaims any responsibility or liability for errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the National Institutes of Health or other parties. The citation of this article must include the following information: author(s), article title, journal title, year of publication and DOI.”

Commercially available antibodies to the LHR are not better for these assays than antibodies to the myc epitope.

The concentrations of cAMP analogs and inhibitors shown in Figures 5 and 6 are the lowest concentrations that elicit maximal activation (cAMP analogs) or the lowest concentrations that elicit a maximal inhibitory effect (chemical inhibitors). These concentrations were chosen empirically (data not shown).

References

- 1.Christensen AK, Peacock KC. Increase in Leydig cell number in testes of adult rats treated chronically wtih an excess of human chorionic gonadotropin. Biol Reprod. 1980;22:383–391. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/22.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teerds KJ, De Rooji DG, Rommerts FFG, Van den Hurk R, Wensing CJG. Stimulation of the proliferation and differentiation of Leydig cell precursors after the destruction of existing Leyidg cells with ethane dimethyl sulphonate (EDS) can take place in the abscene of LH. J Androl. 1989;10:472–477. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.1989.tb00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teerds KJ, De Rooji DG, Rommerts FFG, Wensing CJG. The regulation of the proliferation and differentiation of rat Leydig cell precursor cells after EDS administration or daily hCG treatments. J Androl. 1988;9:343–351. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.1988.tb01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latronico AC, Segaloff DL. Naturally occurring mutations of the luteinizing-hormone receptor: lessons learned about reproductive physiology and G protein-coupled receptors. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:949–958. doi: 10.1086/302602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Themmen APN, Huhtaniemi IT. Mutations of gonadotropins and gonadotropin receptors: elucidating the physiology and pathophysiology of pituitary-gonadal function. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:551–583. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ascoli M, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor. A 2002 perspective. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:141–174. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.2.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Themmen APN. An update of the pathophysiology of human gonadotrophin subunit and receptor gene mutations and polymorphisms. Reproduction. 2005;130:263–274. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu G, Duranteau L, Carel J-C, Monroe J, Doyle DA, Shenker A. Leydig-cell tumors caused by an activating mutation of the gene encoding the luteinizing hormone receptor. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1731–1736. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter-Unruh A, Wessels HT, Menken U, Bergmann M, Schittmann-Ohters K, Schaper J, Tapeser S, Hauffa BP. Male LH-independent sexual precocity in a 3.5-year-old boy caused by a somatic activating mutation of the LH receptor in a Leydig cell tumor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1052–1056. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canto P, Soderlund D, Ramon G, Nishimura E, Mendez JP. Mutational analysis of the luteinizing hormone receptor gene in two individuals with Leydig cell tumors. Am J Med Genet. 2002;108:148–152. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar TR. What have we learned about gonadotropin function from gonadotropin subunit and receptor knockout mice? Reproduction. 2005;130:293–302. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rulli SB, Huhtaniemi I. What have gonadotrophin overexpressing transgenic mice taught us about gonadal function? Reproduction. 2005;130:283–291. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huhtaniemi IT, Rullin S, Ahtiainen P, Poutanen M. Multiple sites of tumorigenesis in transgenic mice overproducing hCG. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;234:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker PJ, O'Shaughnessy PJ. Role of gonadotropins in regulating numbers of Leydig and Sertoli cells during fetal and postnatal development in mice. Reproduction. 2001;122:227–234. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang F-P, Poutanen M, Wilbertz J, Huhtaniemi I. Normal Prenatal but Arrested Postnatal Sexual Development of Luteinizing Hormone Receptor Knockout (LuRKO) Mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:172–183. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei ZM, Mishra S, Zou W, Xu B, Foltz M, Li X, Rao CV. Targeted Disruption of Luteinizing Hormone/Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Receptor Gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:184–200. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Risma KA, Clay CM, Nett TM, Wagner T, Yun J, Nilson JH. Targeted overexpression of luteinizing hormone in transgenic mice leads to infertility, polycystic ovaries, and ovarian tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1995;92:1322–1326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar TR, Wang Y, Matzuk MM. Gonadotropins are essential modifier factors for gonadal tumor development in inhibin-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4210–4216. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.10.8828479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kananen K, Rillianawati Paukku T, Markkular M, Rainio E-M, Huhtaniemi IT. Suppression of gonadotropins inhibits gonadal tumorogenesis in mice transgenic for the mouse inhibin-a subunit promoter/SV40 T-antigen fusion gene. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3521–3531. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.8.5316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prahalada S, Majka JA, Soper KA, Nett TA, Bagdon WJ, Peter CP, Burek JD, MacDonald JS, van Zwieten MJ. Leydig cell hyperplasia and adenomas in mice treated with finasteride, a 5α-reductase inhibitor: a possible mechanism. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1994;22:211–219. doi: 10.1006/faat.1994.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rilianawati, Paukku T, Kero J, Zhang F-P, Rahman N, Kananen K, Huhtaniemi I. Direct luteinizing hormone action triggers adrenocortical tumorigenesis in castrated mice transgenic for the murine inhibin α-subunit promoter/simian virus 40 T-antigen fusion gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;12:801–809. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.6.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kero J, Poutanen M, Zhang FP, Rahman N, McNicol AM, Nilson JH, Keri RA, Huhtaniemi IT. Elevated luteinizing hormone induces expression of its receptor and promotes steroidogenesis in the adrenal cortex. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:633–641. doi: 10.1172/JCI7716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cameron M, Foster J, Bukovsky A, Wimalasena J. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by gonadotropins and cyclic adenosine 5'-monophosphates in porcine granulosa cells. Biol Reprod. 1996;55:111–119. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salvador LM, Maizels E, Hales DB, Miyamoto E, Yamamoto H, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Acute signaling by the LH receptor is independent of protein kinase C activation. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2986–2994. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.8.8976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seger R, Hanoch T, Rosenberg R, Dantes A, Merz WE, Strauss JF, III, Amsterdam A. The ERK Signaling Cascade Inhibits Gonadotropin-stimulated Steroidogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13957–13964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirakawa T, Ascoli M. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR)-induced phosphorylation of the extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERKs) in Leydig cells is mediated by a protein kinase A-dependent activation of Ras. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2189–2200. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiraishi K, Ascoli M. Activation of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells stimulates tyrosine kinase cascades that activate Ras and the extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERK1/2) Endocrinology. 2006;147:3419–3427. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinelle N, Holst M, Soder O, Svechnikov K. Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases Are Involved in the Acute Activation of Steroidogenesis in Immature Rat Leydig Cells by Human Chorionic Gonadotropin. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4629–4634. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andric N, Ascoli M. A delayed, gonadotropin-dependent and growth-factor mediated activation of the ERK1/2 cascade negatively regulates aromatase expression in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3308–3320. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonald CA, Millena AC, Reddy S, Finlay S, Vizcarra J, Khan SA, Davis JS. FSH-Induced Aromatase in Immature Rat Sertoli Cells Requires an Active Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase Pathway and is Inhibited via the Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Signaling Pathway. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:608–618. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardy MP, Kelce WR, Klinefelter GR, Ewing LL. Differentiation of Leydig cell precursors in vitro: a role for androgen. Endocrinology. 1990;127:488–490. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-1-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen H, Hardy MP, Zirkin BR. Age-related decreases in Leydig cell testosterone production are not restored by exposure to LH in vitro. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1637–1642. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.5.8802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svechnikov KV, Sultana T, Soder O. Age-dependent stimulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis by interleukin-1 isoforms. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;182:193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shan L-X, Hardy MP. Developmental changes in levels of luteinizing hormone receptor and androgen receptor in rat Leydig cells. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1107–1114. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1505454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen H, Liu J, Luo L, Zirkin BR. Dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate restores the ability of aged Leydig cells to produce testosterone at the high levels characteristic of young cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4441–4446. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colon E, Zaman F, Axelsson M, Larsson O, Carlsson-Skwirut C, Svechnikov KV, Soder O. Insulin-like growth factor-I is an important anti-apoptotic factor for rat Leydig cells during postnatal development. Endocrinology. 2007;148:128–139. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carpenter G, Cohen S. Human epidermal growth factor and the proliferation of human fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 1976;88:227–238. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040880212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan S, Teerds K, Dorrington J. Growth factor requirements for DNA synthesis by Leydig cells from the immature rat. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:335–341. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ge R-S, Hardy MP. Decreased cyclin A2 and increased cyclin G1 levels coincide with loss of proliferative capacity in rat Leydig cells during pubertal development. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3719–3726. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan SA, Khan SJ, Dorrington JH. Interleukin-1 stimulates deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in immature rat Leydig cells in vitro. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1853–1857. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.4.1396331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan SA, Teerds K, Dorrington J. Steroidogenesis-inducing protein promotes deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in Leydig cells from immature rats. Endocrinology. 1992;130:599–606. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.2.1733710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirakawa T, Galet C, Ascoli M. MA-10 cells transfected with the human lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (hLHR). A novel experimental paradigm to study the functional properties of the hLHR. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1026–1035. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.3.8702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ascoli M. Characterization of several clonal lines of cultured Leydig tumor cells: gonadotropin receptors and steroidogenic responses. Endocrinology. 1981;108:88–95. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-1-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donadeu FX, Ascoli M. The Differential Effects of the Gonadotropin Receptors on Aromatase Expression in Primary Cultures of Immature Rat Granulosa Cells Are Highly Dependent on the Density of Receptors Expressed and the Activation of the Inositol Phosphate Cascade. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3907–3916. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mizutani T, Shiraishi K, Welsh T, Ascoli M. Activation of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor (LHR) in MA-10 cells leads to the tyrosine phosphorylation of the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) by a pathway that involves Src family kinases. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:619–630. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benton L, Shan L-X, Hardy MP. Differentiation of adult Leydig cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;53:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00022-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chamindrani Mendis-Handagama SML, Siril Ariyaratne HB. Differentiation of the Adult Leydig Cell Population in the Postnatal Testis. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:660–671. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carpenter G, Cohen S. Epidermal growth factor. Annual Reviews of Biochemistry. 1979;48:193–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Enserink JM, Christensen AE, de Rooij J, van Triest M, Schwede F, Genieser HG, Doskeland SO, Blank JL, Bos JL. A novel Epac-specific cAMP analogue demostrates independent regulation of Rap1 and ERK. Nature Cell Bio. 2002;4:901–906. doi: 10.1038/ncb874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christensen AE, Selheim F, de Rooij J, Dremier S, Schwede F, Dao KK, Martinez A, Maenhaut C, Bos JL, Genieser H-G, Doskeland SO. cAMP Analog Mapping of Epac1 and cAMP Kinase: DISCRIMINATING ANALOGS DEMONSTRATE THAT Epac AND cAMP KINASE ACT SYNERGISTICALLY TO PROMOTE PC-12 CELL NEURITE EXTENSION. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35394–35402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bos JL. Epac: a new cAMP target and new avenues in cAMP research. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:733–738. doi: 10.1038/nrm1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown S, Meroueh SO, Fridman R, Mobashery S. Quest for selectivity in inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;4:1227–1238. doi: 10.2174/1568026043387854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gether U. Uncovering molecular mechanisms involved in activation of G protein- coupled receptors. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:90–113. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang G, Hardy MP. Development of Leydig Cells in the Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I (IGF-I) Knockout Mouse: Effects of IGF-I Replacement and Gonadotropic Stimulation. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:632–639. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.022590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park J-Y, Su Y-Q, Ariga M, Law E, Jin SLC, Conti M. EGF-like growth factors as mediators of LH action in the ovulatory follicle. Science. 2004;303:682–684. doi: 10.1126/science.1092463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hsieh M, Lee D, Panigone S, Horner K, Chen R, Theologis A, Lee DC, Threadgill DW, Conti M. Luteinizing Hormone-Dependent Activation of the Epidermal Growth Factor Network Is Essential for Ovulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1914–1924. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01919-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stocco DM, Wang X, Jo Y, Manna PR. Multiple Signaling Pathways Regulating Steroidogenesis and StAR Expression: More Complicated Than We Thought. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2647–2659. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teerds KJ. Regeneration of Leydig cells after depletion by EDS. A model for postnatal Leydig cell renewal. In: Payne AH, Hardy MP, Russell LD, editors. The Leydig cell. Vienna, IL: Cache River Press; 1996. pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tena-Sempere M, Rannikko A, Kero J, Zhang FP, Huhtaniemi IT. Molecular Mechanisms of Reappearance of Luteinizing Hormone Receptor Expression and Function in Rat Testis after Selective Leydig Cell Destruction by Ethylene Dimethane Sulfonate. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3340–3348. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.8.5325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Molenaar R, de Rooij DG, Rommerts FF, van der Molen HJ. Repopulation of Leydig cells in mature rats after selective destruction of the existent Leydig cells with ethylene dimethane sulfonate is dependent on luteinizing hormone and not follicle-stimulating hormone. Endocrinology. 1986;118:2546–2554. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-6-2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee VW, de Kretser DM, Hudson B, Wang C. Variations in serum FSH, LH and testosterone levels in male rats from birth to sexual maturity. J Reprod Fertil. 1975;42:121–126. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0420121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]