Abstract

Soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) is a cytosolic enzyme producing the intracellular messenger cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) on activation with nitric oxide (NO). sGC is an obligatory heterodimer composed of α and β subunits. We investigated human β1 sGC transcriptional regulation in BE2 human neuroblastoma cells. The 5′ upstream region of the β1 sGC gene was isolated and analyzed for promoter activity by using luciferase reporter constructs. The transcriptional start site of the β1 sGC gene in BE2 cells was identified. The functional significance of consensus transcriptional factor binding sites proximal to the transcriptional start site was investigated by site deletions in the 800-bp promoter fragment. The elimination of CCAAT-binding factor (CBF) and growth factor independence 1 (GFI1) binding cores significantly diminished whereas deletion of the NF1 core elevated the transcription. Electrophoretic mobility-shift assay (EMSA) and Western analysis of proteins bound to biotinated EMSA probes confirmed the interaction of GFI1, CBF, and NF1 factors with the β1 sGC promoter. Treatment of BE2 cells with genistein, known to inhibit the CBF binding to DNA, significantly reduced protein levels of β1 sGC by inhibiting transcription. In summary, our study represents an analysis of the human β1 sGC promoter regulation in human neuroblastoma BE2 cells and identifies CBF as a critically important factor in β1 sGC expression.

Nitric oxide (NO)-mediated signaling has been implicated in vasodilatation, inhibition of leukocyte adhesion and platelet aggregation, regulation of endothelial permeability, neural signaling in the peripheral and central nervous system, and other processes (1–4). Soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) constitutes the major receptor for NO in vivo and mediates many of its physiological actions. sGC functions as an obligatory heterodimer (5). Several isoforms of the α and β sGC subunits have been cloned in various species (6). In mammals, two isoforms of each subunit, designated as α1,2 and β1,2, were identified (7). So far, only α1/β1 and α2/β1 heterodimers have been found at the protein level. Human vascular smooth muscle, vascular endothelial cells, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum express predominantly α1 and β1 subunits (8).

Since the discovery of sGC 30 yr ago, the biochemical properties of this enzyme have been relatively well characterized. However, the regulation of sGC gene expression has been poorly explored. Emerging data in the literature indicate that regulation of sGC expression could be an important factor in the modulation of sGC activity. Changes in sGC levels and activity were demonstrated during mouse kidney and pulmonary development and the development of the rat brain (6). Down-regulation of sGC expression was suggested to be an early event in the pathogenesis of hypertension, arterial dysfunction, and salt sensitivity and is associated with impaired vasodilatory potency during aging in rats (9).

Among the sGC subunit isoforms, β1 seems to be the most functionally significant. It was found expressed ubiquitously in all tissues, and so far only sGC heterodimers containing β1 have been shown to have catalytic activity in vivo. The α1/β1 sGC is expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells and is believed to be an important player in blood pressure regulation (10). Decreases in β1 expression were associated with aging, changes in vasodilatory potency, and salt-sensitivity in rats (6). Increases in β1 subunit level were associated with altered vasodilator response in aortic rings from rats after myocardial infraction (11). Expression of the β1 subunit was also shown to be developmentally regulated in fish embryos (12) and rat lung and brain (6, 13).

The promoter regions for the mammalian sGC genes have not been characterized thus far. In the present study, we initiated an analysis of transcriptional regulation of human sGC genes. We isolated and performed a detailed analysis of the β1 sGC gene promoter region and identified CCAAT-binding factor (CBF, NF-Y) as a transcriptional activator obligatory for β1 sGC constitutive expression.

Materials and Methods

Cell Cultures. BE2 human neuroblastoma cell line (American Type Culture Collection) was cultured in 1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12K media (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma), 0.1 mM MEM nonessential amino acids, penicillin-streptomycin mixture (50 units/ml and 50 μg/ml), 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM l-glutamine (all from Gibco) and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Isolation of Genomic Clones for Human β1 sGC Subunit. A bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) high-density membrane CIT Human D (Release II) library was purchased from IncyteGenomics. Hybridization was performed overnight at 46°C as described (41). A full-size human β1 sGC cDNA fragment (AF 020340) labeled with Prime-a-Gene (Promega) kit was used as a probe. Positive BAC clones were identified by using the manufacturer's procedure and purchased from IncyteGenomics. BAC DNA was isolated by using a BAC purification kit (Clontech) and subjected to restriction digest and Southern blot hybridization analysis by using the same hybridization probe to confirm isolation of positive clones. Presence of β1 sGC exons were verified by sequencing.

RACE Analysis and Identification of the Transcription Start Site of β1 sGC Subunit Gene. Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from 80% confluent BE2 cells with an mRNA extraction kit (Dynal, Great Neck, NY). Determination of the 5′ end of β1 sGC mRNA was performed by using the GeneRacer kit from Invitrogen according to the manufacturer's protocol. A nested downstream primer used for amplification of the 5′ end of cDNA (5′-cat ggt gtc tgc acc ggg agc-3′) was positioned at the end of the first exon of the β1 sGC gene. Amplified cDNA ends were subcloned into a pCR4-Topo vector (Invitrogen), and insertions were sequenced by using the M13 primer. All primers were custom synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

Construction of Luciferase Deletion Plasmids. Different 5′-flanking regions of the β1 sGC gene starting upstream of the identified transcription start site (+1) and extending to the noncoding part of the first exon (+41), were subcloned into the NheI–XhoI restriction sites of the pGL3-basic luciferase reporter vector (Promega). Fragments were obtained by PCR by using sGC genomic clone as template and high fidelity Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The PCR primers used to generate fragments can be found in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. Insertions in the pGL3 reporter vector were identified by restriction digest and confirmed by sequencing.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis. The 844-bp promoter region (–788 bp to +56 bp) incorporated into the p 0.8 construct was subjected to single- and double-site-directed mutagenesis by using the QuikChange Site-Directed approach (Stratagene) and high fidelity Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The PCR primers used to introduce small deletions to eliminate cores of putative transcription binding sites in p 1110 construct can be found in Supporting Text. Double deletions were created by running a second round of mutagenesis by using as template plasmids already containing one mutation. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Transient Transfections and Luciferase Assays. BE2 cells were plated in six-well plates 4 days before transfection with 20% confluency. Two days before transfection, cells were washed twice and replaced with serum-free F12K media (containing penicillin-streptomycin) to promote quiescent state. Cells were transfected with 1 μg of plasmid DNA per well by using Lipofectamine Reagent (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested and resuspended in PBS buffer with a proteinase inhibitor mixture (Sigma). Lysates were prepared by sonication on ice (the Model-225R Sonicator, Ultrasonics, Farmingdale, NY; 10 pulses at 4.5 output, three cycles). Luciferase activity was determined by using the luciferase assay (Promega) on the Monolight 2010 (Analytical Luminescence Laboratory, San Diego) luminometer. Protein concentration in lysates was determined by Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad).

EMSAs. Nuclear extracts from BE2 cells were prepared as described (14). Binding was tested in 10 μl of solution by incubating 4 μg of nuclear extract with a [α-32P]dCTP-radiolabeled probe (100,000 cpm) in the presence or absence of competitor or antibodies, as indicated below, in reaction buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 5 mM EDTA, 25% Glycerol, 0.25 μg/ml poly(dI-dC)poly(dI-dC), 1 mM MgCl2] for 20 min on ice and subsequently 20 min at room temperature. The complex was separated on a 4.8% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 1× Tris-Glycine Buffer for 1.5 h at 130 V at room temperature as described (14). Gels were dried and visualized by autoradiography. The double-stranded oligonucleotides used as EMSA probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by filling in the overhangs by using Klenow DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) as described (14). The PCR primers used to generate double-stranded EMSA probes can be found in Supporting Text. For supershift assays, specific antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were added to the EMSA binding reaction 1 h before the addition of probes and incubated on ice. For competition analysis, unlabeled DNA (5 or 10 molar excess of labeled probe) was incubated with nuclear extracts on ice for 10 min before the addition of the labeled probes.

Isolation of Factors Bound to EMSA Probes. To identify proteins bound to EMSA probes, we used the method described (15). DNA probes were generated by using 5′ biotinated reverse primers for EMSA probes (see sequences above). Double-stranded biotinated DNA probes were generated with Klenow polymerase as described above. Double-stranded biotinated polyadenosine probe (polyA, 20 bp) was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. Four hundred micrograms of protein nuclear extract were incubated with 400 pmol of biotinated oligo and 60 μl of 50% streptavidin-agarose slurry (Sigma) in a total volume of 600 μl with mixing for 2 h. Bead complexes were pelleted by centrifugation, washed three times with PBS containing proteinase inhibitors mixture (Sigma), then proteins bound to beads were eluted by 2× Laemmli buffer, separated by 10% SDS/PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and analyzed by Western blotting.

All antibodies, unless otherwise indicated, were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies for CBF and GFI1 were used at 1:100 dilutions and for NF1 at 1:200 dilutions. Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were acquired from Sigma and were used at 1:15,000 (rabbit) and 1:7,000 (goat) dilutions. Protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus, Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences).

Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis. To determine sGC β1 mRNA levels, real-time quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) was used, as described (16). In brief, 100 ng of total RNA extracted from BE2 cells was used in reverse transcriptase reaction by using SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) with specific oligonucleotide primer corresponding to β1 sGC human sequence (5′-aga agg ctg caa ttc cca g-3′). For the PCR, the negative-strand oligo was the same as mentioned above, and the positive strand was 5′-gtg gtc act cag tgt ggc aa-3′. Fluorescent-labeled primer was used as described (16). Detection of the probe was done with an Applied Biosystems Prism 7700 Sequence Detector (Perkin–Elmer). Data were analyzed by using the sequence detector software.

Results

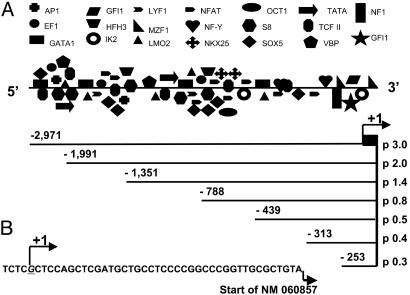

Isolation and Analysis of the 5′-Flanking Region for β1 sGC Gene. Four overlapping BAC clones were isolated for the human β1 sGC gene by screening of a BAC human genomic library with a probe containing the full β1 cDNA fragment. Genomic organization of the β1 sGC gene was predicted by using NCBI data. Genomic organization and topology of sGC human genes can be found in Supporting Text. The identity of the β1 sGC gene was verified by direct sequencing using primers nested in exon regions. We selected one β1 sGC clone containing more than a 4-kb DNA fragment upstream of the first exon. The sequence of the 5′-flanking region of the β1 sGC gene was analyzed by using matinspector V2.2 software for the presence of transcription binding sites (solution parameters: core similarity 1.0; matrix similarity 0.9). The β1 sGC 5′ UTR region revealed a variety of putative transcription binding sites, which seem to be clustered along the length of the 5′ DNA fragment (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

The 5′ UTR of the β1 sGC gene and deletional constructs. (A) Schematic representation of the 5′ UTR with indicated putative transcriptional binding sites. Analysis of 3 kb of the 5′ UTR of the β1 gene was performed by using the matinspector V2.2 software (solution parameters: core similarity 1.0, matrix similarity 0.95). Promoter fragments subcloned into the pGL3 reporter vector are shown. Positions of the 5′ and 3′ ends relative to transcriptional start site for each fragment are indicated. (B) Position of the identified transcriptional start site in the proximal promoter sequence relative to the start site previously reported (NM 060857) is indicated as +1.

Identification of Transcription Start Site. To identify the transcription start site of the β1 sGC gene, we performed 5′ RACE analysis by using mRNA isolated from BE2 cells. The Invitrogen GeneRacer kit was chosen because it offers the selective amplification of full-length transcripts discriminating against truncated messages. A single transcription start site was identified and mapped 40 bp upstream of the 5′ end of the NM 060857 β1 sGC cDNA clone, containing the longest 5′ UTR among other human β1 sGC cDNA sequences deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information library (Fig. 1B).

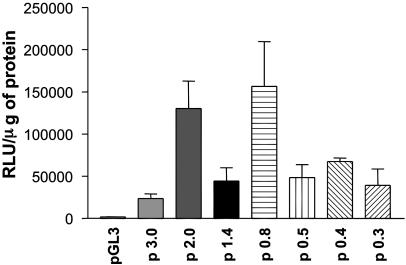

Analysis of Promoter Activity in the 5′-Flanking Region. The human neuroblastoma BE2 cell line was chosen as a cell model to investigate transcriptional activity. This cell line consistently expresses high levels of the α1/β1 sGC heterodimer. Transiently transfected luciferase reporter constructs harboring 0.3–3.0 kb of β1 sGC upstream sequence were analyzed for promoter activity (Figs. 1 A and 2). The p 0.8 construct containing ≈800 bp upstream showed the highest level of activity. The changes in activity among p 0.8, p 1.4, and p 2.0 would indicate the presence of a repressor(s) between –788 and –1351 bp, and an enhancer element(s) located between –1351 and –1991 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site. Extension of the promoter fragment up to 3 kb in length decreased the transcriptional activity of the p 3.0 construct; however, it remained significantly higher than control pGL3. The 350-bp deletion in p 0.8 (construct p 0.5) caused a 3-fold decrease in activity, suggesting that a putative enhancer(s) was located between –788 and –439 bp. Subsequent minimization did not introduce significant changes, with the shortest p 0.3 (0.3 kb) construct possessing ≈25% of the activity of p 0.8, suggesting that the 294-bp fragment contains all crucial elements necessary to support basal transcription of the β1 sGC gene.

Fig. 2.

Promoter activity of β1 sGC deletion constructs in BE2 cells. BE2 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter constructs containing different size promoter fragments. Promoter activity for each construct was measured in relative light units per μg of protein lysate. Results are means ± SD (n = 9).

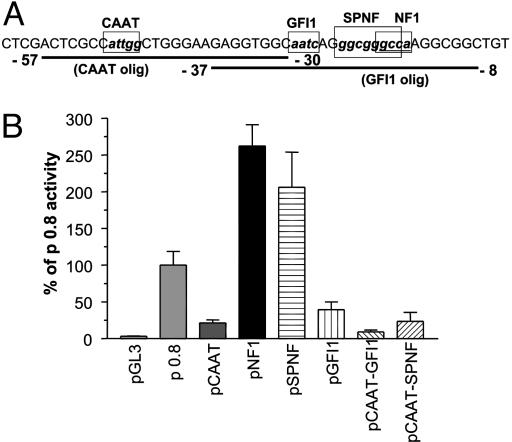

Identification of Critical Transcription Binding Sites. To identify transcription factors crucial for β1 sGC promoter activity, we introduced small deletions in the p 0.8 construct containing the 829-bp fragment (–788 bp to +41 bp). We chose this fragment because it possessed maximal promoter activity. Putative binding sites for CAAT, GFI1, NF1, and SP1 transcription factors located at the optimal regulatory distance from the transcription start site were investigated. The cores of these transcriptional factor binding sites were deleted individually in the p 0.8 construct via site-directed mutagenesis. The deleted nucleotides are denoted by boxes in Fig. 3A. The core deletions did not introduce any new binding sites as confirmed by sequence analysis with matinspector V2.2 software. Transcriptional activity of generated mutant constructs was assessed in BE2 cells (Fig. 3B). The activity of the pCAAT construct containing the CCAAT binding site deletion decreased ≈5-fold in comparison with p 0.8 control. Removal of the GFI1 binding site (pGFI1 construct) diminished the transcriptional activity >2-fold. The construct containing both deletions had <10% of p 0.8 activity, strongly suggesting that CAAT and GFI1 binding sites are the major determinants of the β1 sGC promoter function in BE2 cells.

Fig. 3.

(A) The proximal promoter sequence of the human β1 sGC gene. Circumscribed boxes indicate the cores of binding sites for transcriptional factors CBF, GFI1, Sp1, and NF1 that were deleted in reporter constructs and EMSA oligos. EMSA oligonucleotide probe sequences are underlined, and positions of the 5′ and 3′ ends of each oligonucleotide relative to the transcriptional start site are indicated. (B) Effects of core deletions for CBF, NF1, GFI1, and SP1 factors on activity of the p 0.8 construct. BE2 cells were transfected with the p 0.8 luciferase construct containing singular core deletions of CBF (pCAAT), NF1 (pNF1), and GFI1 (pGFI1) binding sites; double core deletions of CBF and GFI1 (pCAAT-GFI1) binding sites, of SP1 and NF1 (pSPNF) binding sites; and triple core deletion of SP1, NF1 and CBF (pCAAT-SPNF) binding sites. Activity was measured in relative light units per μg of protein lysates and expressed as the percentage of control p 0.8 plasmid activity. Results are means ± SD (n = 9).

In contrast to the CAAT and GFI1 binding sites deletions, the deletion of the NF1 core (pNF1 construct) increased the transcriptional activity >2-fold (Fig. 3B). The double deletion SP1 and NF1 cores (pSPNF construct) did not have a significant effect in comparison with the pNF1 construct (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the NF1 site serves an inhibitory role, and that SP1 does not play a critical role in β1 sGC promoter regulation. We attempted to compensate for the low activity of the pCAAT mutant by introducing a SPNF double core deletion to the same construct. However, this additional mutation did not produce significant augmentation of the activity (<2%, Fig. 3B), confirming that the integrity of the CCAAT site is crucial for the β1 sGC promoter activity, and suggesting that the CCAAT and NF1 sites act independently from each other.

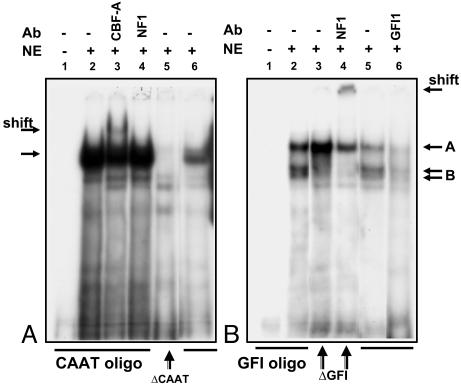

Identification of Transcription Factors Bound to CCAAT, GFI1, and NF1 Elements. To determine proteins bound to the transcriptional sites identified in the promoter analysis, nuclear extracts from BE2 cells were analyzed by EMSA using labeled DNA sequences. One major and three minor complexes were detected by using the oligonucleotide probe containing the –57- to –30-bp region (CAAT oligo) upstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig. 4A, lane 2). The specificity of the major complex was demonstrated by a reduction of the major band intensity in the presence of a 5-fold excess of unlabeled probe (lane 6). Addition of a 10-fold excess of unlabeled probe eliminated the binding completely (data not shown). The deletion of the core of the CCAAT binding site (attgg) abolished formation of the major complex (Fig. 4A, lane 5). Several transcriptional factors are able to bind the CCAAT consensus sequence, among them CBF (NF-Y), NF1, and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) isoforms (CEBP-α, CEBP-β, CEBP-γ, CEBP-δ, and CEBP-ε). To identify the transcriptional factors bound to the CAAT probe, we performed a supershift analysis by using antibodies toward the putative factors. A partial supershift and depletion of major complex were achieved with an antibody against CBF-A, one of the subunits of CBF (Fig. 4A, lane 3), but not against NF-1 (Fig. 4A, lane 4) or any of the C/EBP isoforms (data not shown). These results indicate that CBF is a component of the protein complex bound to the CAAT probe.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of protein complexes formed with oligonucleotides representing the proximal promoter sequence of β1 sGC gene and BE2 nuclear extracts. Presence of nuclear extracts and competing antibodies are as indicated on top. (A) EMSA using the CAAT oligo incubated with BE2 nuclear extracts. Lane 5 indicates incubation of nuclear extracts performed with the CAAT oligo containing a deletion of the CBF binding core. Lane 6 illustrates competition in the presence of a 5-fold excess of unlabeled CAAT oligo. (B) EMSA using GFI1 oligo incubated with BE2 nuclear extracts. In lanes 3 and 4, incubation with nuclear extracts was performed with GFI oligo containing deletion of GFI1 binding core. Lane 5 illustrates competition in the presence of a 5-fold excess of unlabeled GFI oligo.

The interactions within the GFI1-NF1 element encompassing the –37/–8 region (GFI probe) were also evaluated (Fig. 4B). Three major complexes and one minor complex were formed after incubation of the GFI probe with nuclear extracts from BE2 cells (Fig. 4B, lane 2). The intensity of complexes A and B was significantly reduced in the presence of a 5-fold excess of unlabeled –37/–8 oligonucleotide, suggesting that they are specific (Fig. 4B, lane 5). Addition of a 10-fold excess of unlabeled probe abolished the complexes (data not shown). The deletion of the 4-bp (aatc) core for GFI1 factor binding site disrupted the formation of the double band of complex B (Fig. 4B, lane 3), indicating that the aatc motif is necessary for its formation. The remaining complex A was supershifted in the presence of an antibody against NF1 (Fig. 4B, lane 4), but not in the presence of GFI1 or SP1 antibodies (data not shown), indicating that NF1 is the major component of complex A. We attempted the supershift of complex B by incubating the original GFI probe with an antibody against GFI1 (Fig. 4B, lane 6). The presence of GFI1 antibody induced a decrease of band intensity not only in the B complex, but in all formed complexes, suggesting that formation of protein/DNA complexes with the GFI probe could depend on the availability of the GFI1 factor.

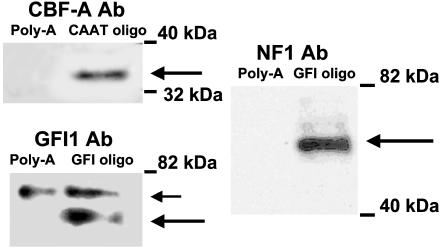

To confirm the identity of transcription factors bound to EMSA DNA probes, we performed Western analysis on the proteins bound to GFI and CAAT oligos employing the method described in ref. 15. Nuclear extract proteins bound to biotinated GFI and CAAT probes were precipitated with streptavidin-agarose, eluted from agarose beads, and analyzed by SDS/PAGE. The data were compared with the control sample containing biotinated polyA probe. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, the presence of CBF-A protein in the eluent from the CAAT probe, and NF1 and GFI1 proteins in the eluent from the GFI probe, were detected. These proteins were not present in the control. These data confirm our observation that CBF-A, NF1, and GFII interact with the proximal β1 sGC promoter region.

Fig. 5.

CBF, GFI1, and NF1 bind to CAAT and GFI oligos according to Western analysis. Proteins bound to biotinated oligonucleotides after incubation with BE2 nuclear extracts were separated by 8% SDS/PAGE and probed with antibodies against CBF-A (CAAT and polyA probes), GFI1, and NF1 (GFI1 and polyA probes). Large arrows indicate the proteins of corresponding size on all panels. In Lower Left, the small arrow indicates a nonspecific protein, bound to both control and GFI oligos and recognized by antibodies against GFI1. The figure is representative of two experiments.

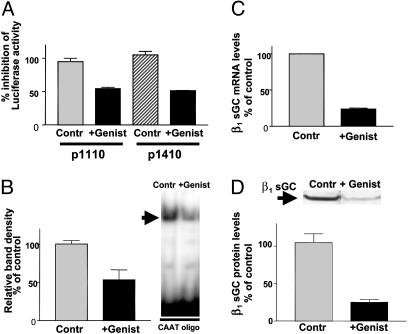

Genistein Decreases the Expression of β1 sGC Protein by Inhibition of Transcription. To investigate the importance of CBF interaction with the promoter on β1 sGC expression, BE2 cells transiently transfected with p 0.8 and p 3.0 constructs, were treated with genistein, a known inhibitor of CBF binding to DNA (17). A 14-h treatment with 140 μM genistein inhibited activity of both constructs by >50% (Fig. 6A), indicating that interaction of CBF with the β1 sGC promoter is important in the context of both fragments (0.8 and 3.0 kb). EMSA with nuclear extracts purified from genistein-treated and untreated BE2 cells confirmed that formation of the major protein complex with the CAAT oligonucleotide probe was significantly decreased with genistein (Fig. 6B). We used real-time Q-PCR analysis to measure the β1 sGC mRNA in BE2 cells treated with genistein (Fig. 6C). We observed a 76% decrease of β1 sGC mRNA in comparison with controls. Lysates from genistein-treated cells demonstrated a reduction in β1 sGC protein content corresponding to the decreased mRNA levels (Fig. 6D), confirming that CBF interaction with the β1 sGC promoter is important for constitutive expression of the protein.

Fig. 6.

Genistein treatment (140 μM for 14 h) inhibits the expression of β1 sGC in BE2 cells via inhibition of transcription. (A) Genistein inhibits activity of p 3.0 and p 0.8 constructs. Protein lysates from BE2 cells transfected with p 0.8 or p 3.0 constructs treated with genistein were assayed for luciferase activity and compared with untreated controls. Data are expressed as percentage of inhibition in comparison with untreated controls. Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 6). (B) Genistein inhibits binding to CAAT oligo. EMSA with CAAT oligonucleotide was performed with nuclear extracts purified from genistein-treated and untreated BE2 cells. EMSA is representative of six experiments with similar results. Densitometry results are shown on a bar graph as mean ± SD (n = 6). (C) Genistein inhibits the transcription of the β1 sGC message. Total RNA was purified from BE2 cells treated with genistein and untreated controls. The β1 sGC mRNA levels were determined by real-time Q-PCR. Mean values ± SEM (n = 3) were normalized to β-actin and are presented as a percentage of control. (D) Genistein decreases the level of β1 sGC protein in BE2 lysates. Equal amounts of protein lysates prepared from genistein-treated and untreated BE2 cells were separated on 8% SDS/PAGE and analyzed by Western analysis with antibodies against human β1 sGC (Sigma). Data are representative of four independent experiments. Densitometry results are shown as mean ± SD (n = 4).

Discussion

Comparison of the genomic organization of α1 and β1 sGC genes between Medaka fish, mouse, and human (species where the sGC genomic organization was resolved) demonstrated several interesting features. The mammalian α1 and β1 sGC genes are further from each other on the chromosome than the Medaka fish genes where they are separated by only 1 kb (18). According to the NCBI database, α1 and β1 sGC genes are separated by 43 kb in human and 60 kb in mouse (see Supporting Text). Although fish genes demonstrate cis-coordinated transcriptional regulation (18), this option is topologically excluded in mammals. This conclusion was supported by the demonstration of independent transcriptional activity of promoters for mouse α1 and β1, and human β1 genes (19). Independent transcription of different sGC subunits existing in mammals could be beneficial in tissue-specific regulation of expression, which was speculated to be one mechanism of regulation of sGC activity (ref. 6 and references therein).

Although in all species examined α1 and β1 sGC colocalize on the same chromosome, mouse and fish genes are positioned sequentially (NCBI database and ref. 18) whereas human genes are facing each other with their 3′ ends (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The orientation of the human α1 and β1 sGC genes on chromosome 4 further increases the distance between promoters of the each subunit, making the possibility of their mutual influence even less likely. However, the transcriptional coordination for their expression could be achieved by using the same transcriptional factors. Interestingly, a comparison of the 5′ UTRs of α1 and β1 sGC genes demonstrate multiple shared putative binding sites (data not shown) that may provide an explanation for synchronized expression of the two subunits.

Analysis of the 5′ UTR of the human β1 sGC gene revealed a multiplicity of putative transcription factor binding sites that seemed to be clustered along the promoter region (see Fig. 1A). The presence of multiple copies of putative binding sites for transcriptional factors involved in hematopoietic development and differentiation, such as GATA1, LMO2, IK2 (20, 21), and factors involved in morphogenesis and development, such as Sox5, Prx2 and Nkx-2.5 (22–24), is noteworthy. The relevance of this observation is substantiated by evidence that sGC activity is important during embryogenesis (12, 13, 25, 26). However, it would require further studies to address the mechanism of β1 sGC transcriptional regulation during development and hematopoiesis.

Functional analysis of constructs containing different size fragments of the 5′-flanking region demonstrated a variable profile of activity, suggesting the presence of several enhancers and repressors functioning at a distance from the regulatory promoter (Fig. 2). The p 0.8 construct demonstrated the highest activity, indicating that the regulatory promoter of the β1 sGC encompasses ≈1 kb preceding the transcriptional start site. In the present report, we focused on characterization of the promoter and identification of the transcriptional factors responsible for the constitutive transcription of β1 sGC in BE2 cells. The β1 sGC gene possesses a TATA-less promoter. Detailed sequence analysis revealed several putative binding sites in the immediate proximity of the start site. Among these sites were CCAAT, GFI1, and overlapping SP1 and NF1 sites (Fig. 3A), all of which have been shown to play an important role in the transcription of a wide variety of eukaryotic genes. One of the CCAAT binding sites is located in reverse orientation 50 bp upstream from the start site. Such placement is considered to be a canonical position for this element and is indicative of its importance in promoter activity (27). Functional analysis with a luciferase reporter construct containing a CCAAT core deletion at this position in the 800-bp promoter fragment demonstrated that the integrity of this site is very important for high levels of transcription (Fig. 3B). Together with EMSA results (Fig. 4A) and Western analysis of the proteins bound to the biotinated EMSA probe (Fig. 5), it strongly suggested that CBF interacts with the β1 sGC promoter and that this interaction is functionally important. To further investigate the extent of CBF regulation on β1 sGC expression, we used the phytoestrogen genistein, which abolishes CBF binding to the CCAAT box by inhibiting tyrosine phosphorylation of the protein (17). Genistein treatment of BE2 had a strong effect on expression of β1 sGC protein by decreasing level of transcription (Fig. 6), indicating that CBF interaction with the β1 sGC promoter is crucial for maintaining a constitutive level of protein expression.

The CBF binding site has been found to be prevalent in the promoters of cell cycle-regulated eukaryotic genes (27) and is known to be essential for cell cycle-dependent activation and repression of several mammalian genes (28–30). The β1 sGC promoter contains a second CCAAT-binding site located 47 bp upstream from the CCAAT site investigated in the present study. Many cell cycle-regulated promoters are known to contain two CBF-binding sites located close to each other, such as the promoters of Cdc2, topoisomerase IIα, Cdc25C, and cyclin B1/B2 (28). The important role CBF plays in β1 sGC transcription and the presence of the two closely situated CBF-binding sites in the immediate promoter suggest that expression of this gene could be regulated during cell cycle.

sGC expression and activity have been associated with neoplastic transformation and growth. NO-mediated increases of cGMP have been shown to promote an antiapoptotic effect in several cell types, including cerebellar granule neurons and SK-N-BE human neuroblastoma cells (31, 32). Elevated levels of sGC expression and high cGMP content were detected in human bladder carcinoma in comparison with normal tissue (33). It has also been recognized that tumors have altered guanylyl cyclase activity and that tumor bearing animals have elevated cGMP urinary excretion (34, 35). Conversely, genistein, has been found to inhibit the growth of carcinogen-induced cancers in rats and human leukemia cells transplanted into mice (36). The inhibition of β1 sGC expression by genistein demonstrated in the present report suggests that one of the anticancer mechanisms of genistein may be related to its ability to reduce the level of β1 sGC expression and consequently NO-dependent generation of cGMP by sGC.

Because the GFI1 and NF1 sites are positioned between the CCAAT site and the transcriptional start site, they are likely to play a role in β1 sGC promoter activity. Both factors influence the activity of the promoter in a different manner according to functional studies with luciferase reporter constructs containing deletions in their respective binding cores (Fig. 4). GFI1 was identified as a protooncogene functioning as a transcriptional repressor and shown to be involved in the inflammatory immune response and the differentiation of myeloid precursors (37, 38). Surprisingly, GFI1 acts as an enhancer in the regulation of the β1 sGC promoter in the BE2 neuroblastoma cell line. It was shown previously that overexpression of GFI1 inhibits cell cycle arrest and differentiation of myeloid cells, which was related to neoplastic transformation (39). The unusual role of GFI1 as an activator for the β1 sGC promoter could be linked to the neoplastic origin of the BE2 cell, but this remains to be proven.

NF1 has been implicated in both activation and repression of promoters through interaction with various coactivator proteins (40). It was demonstrated that competition between NF1 and Sp1 for binding to adjacent sites represses Sp1 activation of the mouse α1(I) collagen promoter, introducing a possible mechanism for tissue specific modulation of expression (41). The NF1 core is adjacent to the Sp1 factor core in the β1 sGC promoter. The deletion of the NF1 core (pNF1 construct), which should facilitate SP1 binding, induced transcriptional activity 2-fold. However, the double deletion of NF1 and SP1 cores (pSPNF) did not have a significant effect in comparison with the pNF1 construct (Fig. 4). Even so, it is possible that NF1 and SP1 competition for adjacent binding sites could play a role in modulation of the transcriptional activity of the β1 sGC promoter in different cell types.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. K. Cieslik for technical advice and A. R. Seminara for careful review of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from J. S. Dunn, the Mathers and Welsh Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Abbreviations: sGC, soluble guanylyl cyclase; CBF, CCAAT-binding factor; BAC, bacterial artificial chromosome; C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility-shift assay; polyA, polyadenosine; GFI1, growth factor independence 1.

References

- 1.Zhuo, M. & Hawkins, R. D. (1995) Rev. Neurosci. 6, 259–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter, U. (1989) Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 113, 41–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapoport, R. M. & Murad, F. (1983) J. Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphor. Res. 9, 281–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moncada, S. & Higgs, E. A. (1995) FASEB J. 9, 1319–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamisaki, Y., Saheki, S., Nakane, M., Palmieri, J. A., Kuno, T., Chang, B. Y., Waldman, S. A. & Murad, F. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 7236–7241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andreopoulos, S. & Papapetropoulos, A. (2000) Gen. Pharmacol. 34, 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zabel, U., Weeger, M., La, M. & Schmidt, H. H. (1998) Biochem. J. 335, 51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hobbs, A. J. (1997) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 18, 484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kloss, S., Bouloumie, A. & Mulsch, A. (2000) Hypertension 35, 43–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothermund, L., Friebe, A., Paul, M., Koesling, D. & Kreutz, R. (2000) Br. J. Pharmacol. 130, 205–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauersachs, J., Bouloumie, A., Fraccarollo, D., Hu, K., Busse, R. & Ertl, G. (1999) Circulation 100, 292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto, T., Yao, Y., Harumi, T. & Suzuki, N. (2003) Zool. Sci. 20, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smigrodzki, R. & Levitt, P. (1996) Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 97, 226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin, E., Nathan, C. & Xie, Q. W. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 180, 977–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu, Y., Saunders, M. A., Yeh, H., Deng, W. G. & Wu, K. K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6923–6928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krumenacker, J. S., Hyder, S. M. & Murad, F. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 717–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou, Y. & Lee, A. S. (1998) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikami, T., Kusakabe, T. & Suzuki, N. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18567–18573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharina, I. G., Krumenacker, J. S., Martin, E. & Murad, F. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 10878–10883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitt, C., Tonnelle, C., Dalloul, A., Chabannon, C., Debre, P. & Rebollo, A. (2002) Apoptosis 7, 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wadman, I. A., Osada, H., Grutz, G. G., Agulnick, A. D., Westphal, H., Forster, A. & Rabbitts, T. H. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 3145–3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smits, P. & Lefebvre, V. (2003) Development 130, 1135–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ten Berge, D., Brouwer, A., Korving, J., Reijnen, M. J., van Raaij, E. J., Verbeek, F., Gaffield, W. & Meijlink, F. (2001) Development 128, 2929–2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jamali, M., Rogerson, P. J., Wilton, S. & Skerjanc, I. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 42252–42258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloch, K. D., Filippov, G., Sanchez, L. S., Nakane, M. & de la Monte, S. M. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 272, L400–L406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harumi, T., Watanabe, T., Yamamoto, T., Tanabe, Y. & Suzuki, N. (2003) Zool. Sci. 20, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantovani, R. (1999) Gene 239, 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salsi, V., Caretti, G., Wasner, M., Reinhard, W., Haugwitz, U., Engeland, K. & Mantovani, R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6642–6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu, Q., Bhattacharya, C. & Maity, S. N. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37191–37200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu, Q. & Maity, S. N. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4435–4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciani, E., Guidi, S., Della Valle, G., Perini, G., Bartesaghi, R. & Contestabile, A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49896–49902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciani, E., Guidi, S., Bartesaghi, R. & Contestabile, A. (2002) J. Neurochem. 82, 1282–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ehsan, A., Sommer, F., Schmidt, A., Klotz, T., Koslowski, J., Niggemann, S., Jacobs, G., Engelmann, U., Addicks, K. & Bloch, W. (2002) Cancer 95, 2293–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murad, F., Kimura, H., Hopkins, H. A., Looney, W. B. & Kovacs, C. J. (1975) Science 190, 58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimura, H. & Murad, F. (1975) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72, 1965–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou, J. R., Mukherjee, P., Gugger, E. T., Tanaka, T., Blackburn, G. L. & Clinton, S. K. (1998) Cancer Res. 58, 5231–5238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karsunky, H., Zeng, H., Schmidt, T., Zevnik, B., Kluge, R., Schmid, K. W., Duhrsen, U. & Moroy, T. (2002) Nat. Genet. 30, 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karsunky, H., Mende, I., Schmidt, T. & Moroy, T. (2002) Oncogene 21, 1571–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tong, B., Grimes, H. L., Yang, T. Y., Bear, S. E., Qin, Z., Du, K., El-Deiry, W. S. & Tsichlis, P. N. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 2462–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gronostajski, R. M. (2000) Gene 249, 31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nehls, M. C., Rippe, R. A., Veloz, L. & Brenner, D. A. (1991) Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 4065–4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.