Abstract

Prostaglandins (PGs) play important roles in mammalian reproductive function through autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine actions. However, they predominate as charged anions and diffuse poorly across the plasma membrane. Recently, a PG transporter (PGT) has been found to mediate PG transport across cell membranes. In ruminants, endometrial PGs are transported by a vascular pathway to the ovary to regress or rescue the corpus luteum. There is no report on the role of PGT in the reproductive functions of any species. We have cloned and characterized the bovine PGT (bPGT) that transports different PGs in the following affinity order: PGE2 = PGF2α ≥ PGD2 much greater than arachidonate. bPGT mRNA and protein are expressed in endometrium, myometrium, and the utero-ovarian plexus (UOP) during the estrous cycle. The level of bPGT expression is higher in endometrium and UOP on the side of corpus luteum between days 13 and 18 of the estrous cycle. bPGT protein is localized in endometrial stroma, luminal epithelial cells, myometrial smooth muscle cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells of uterine vein and artery. In UOP, bPGT is selectively expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells of uterine vein and ovarian artery. Spatio-temporal expression of bPGT in uterine tissues and UOP supports a significant role of bPGT in cellular and compartmental transport of PGs to mediate the endocrine action at the time of luteolysis or establishment of pregnancy in bovine. This study describes and proposes a role of PGT in the regulation of reproductive processes.

Prostaglandins (PGs) are local mediators produced by a variety of tissues and play important roles in many physiological and pathological processes (1). PGs exert their effects primarily through cell surface G protein-coupled receptors and also through nuclear receptors in an autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine manner (2–4). Arachidonic acid (AA), stored in membrane phospholipids, is the primary precursor for PGs. AA is converted into PGH2 by cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2. PGH2 is then converted into different PGs (PGE2, PGF2α, PGD2, PGI2, and TxA2) by specific PG synthases (1).

In female reproduction, PGs play pivotal roles in several processes, such as luteolysis, and return to estrous cycle, ovulation, fertilization, implantation, pregnancy, and parturition. Indeed, improper production and action of PGs lead to multiple reproductive failures (4–8). The roles of PGs in various reproductive events have been particularly well documented in ovine and bovine species. In ruminants, the uterus is the primary site of PGF2α and PGE2 production during the estrous cycle. Endometrial PGF2α is known as the luteolysin (8, 9), whereas PGE2 has been proposed as a temporary luteostatic and immunomodulatory signal (10, 11) at the time of establishment of pregnancy. For more than a decade we have used the bovine model to explore the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in the regulation of endometrial production of PGs and the associated signal transduction. We have found that the PG metabolic enzymes COX-1, COX-2, PGFS, PGES, and PGDH and PG receptors FP, EP2, EP3, and EP4 are expressed and regulated in endometrium during the estrous cycle (12–16). The mechanisms involved in the transport of PGs across cells and tissues are poorly documented, which constitutes a major limitation for the understanding of the endocrine, autocrine, and paracrine actions of PGs in the reproductive system.

Endometrial PGF2α and/or PGE2 enter into the venous circulation and are transported by a vascular pathway from the uterine to ovarian compartment to effect the endocrine action, luteolysis, or luteostasis in most mammalian species (8, 9). In ruminants, a unique structure where the uterine vein comes in close apposition to an ovarian artery called utero-ovarian plexus (UOP) has been identified as the primary site of PG transfer. The anatomical and physiological importance of UOP in ruminants and other species has been well described (17, 18). In ruminants, 65–99% of circulating PGs are metabolized after a single passage through lungs (8). In pigs, the action of endometrial PGF2α is explained by an endocrine and exocrine theory where endometrial PGF2α is released toward the circulation to effect luteolysis or toward the uterine lumen at the time of recognition of pregnancy (19). This theory requires selective transport of PGs that cannot be supported by passive transport. The mechanisms involved in the transport of PGs across cell membranes and compartmental transport of PGs from the uterine vein to the ovarian artery are not known, but were proposed to range from simple diffusion, passive transport, active transport, and counter current exchange (8, 20, 21).

PGs predominate as charged anions and diffuse poorly through plasma membranes despite their lipid nature (20, 21). It has been shown that although anions (PGs) cross the membrane by simple diffusion, the estimated flow rate is too low to maintain a biological function (22). Therefore, a carrier-mediated transport mechanism is needed for organic anions such as PGs to cross the biological membranes. Recently, PG transporter (PGT) has been identified in rat kidney (23), human liver (24), and mouse lung (25). PGT belongs to the super family of 12-transmembrane organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs) (20, 21). It has been proposed that PGT mediates both the efflux of newly synthesized PGs to effect their biological actions through their cell surface receptors and influx of PGs from the extracellular milieu for their inactivation (20) or action through specific nuclear receptors (3). PGT was found to be highly expressed in cells producing more PGs (26). Identification of PGT in lung, liver, and kidney suggests its role in PG transport in metabolic clearance of PGs (20, 21, 26). However, PGT is also expressed in other tissues such as brain, stomach, intestine, prostate, testis, ovary, and uterus (23, 24). The overwhelming evidence of the importance of paracrine or endocrine action of PGs in biological processes indirectly suggests that PGT is not only involved in metabolic clearance of PGs but also in physiological and/or pathological processes, including reproduction.

Given the strategic role of PGs in female reproductive functions, we hypothesized that PGT might mediate cellular and compartmental transport of PGs in reproductive tissues. In this study, we used a bovine model well known to us to investigate the role of PGT in the reproductive system. Our objectives were to (i) clone and characterize the bovine PGT (bPGT), (ii) study the role of PGT primarily in endometrium and myometrium throughout the estrous cycle, and (iii) study the expression of PGT in UOP during the estrous cycle. Our results show that PGT is an important molecule likely to be involved in the cellular transport of PGs in endometrium and myometrium, and in compartmental transport of endometrial PGs in UOP to effect the endocrine action of these mediators in the bovine reproductive system.

Materials and Methods

Details about materials and methods are provided in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. Collection of bovine tissues, uteri, and UOP and preparation of tissues and classification of days of the estrous cycle were done as described (12, 17, 18). DNA, RNA, and protein processing were also performed as described (27, 28). Detailed schematic illustration and description of the PCR cloning strategies and primers used are given in Supporting Text and Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Cloning and characterization of bPGT (13, 15), structural, hydropathic, and sequence analyses (29, 30) were performed as described. Polyclonal anti-bPGT antibody was generated and validated (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, and Supporting Text) (13, 15). Northern, Western, and immunohistochemical analyses were used (12, 13, 15). Transient transfection of bPGT in HeLa cells (15, 31) and influx and efflux experiments in the presence or absence of trans substrate and/or anion transport inhibitors were conducted and validated (32). Expression of bPGT in various bovine tissues and in endometrium, myometrium, and UOP during different days of the estrous cycle was studied. Data were analyzed statistically.

Results

Molecular Characterization of bPGT. The bPGT cDNA (GenBank accession no. AY 134618) ORF consists of 1,935 nt and encodes 644 aa with a calculated molecular mass of ≈70.4 kDa (Fig. 9A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Hydropathy analysis reveals the presence of 12 hydrophobic regions consistent with other members of the OATP super-family. The predicted amino acid sequence of bPGT possesses 90%, 82%, and 81% identity with the human, mouse, and rat homologues (Fig. 9B). The corresponding homology of bPGT to the human OATP-A, mouse OATP-1, and rat OAT-K1 is 30%, 31%, and 30%, respectively. Most of the sequence divergence of bPGT with other members of PGT appears in extracellular loops and cytoplasmic loops, whereas a high degree of sequence homology (≈95%) is found in the putative transmembrane domains.

Expression of bPGT in Various Bovine Tissues. Northern analysis indicates that the bPGT transcript is expressed at ≈4.0 kb in all tissues. The level of expression of bPGT mRNA is higher in lung, kidney, endometrium, and corpus luteum (CL), moderate in brain, heart, liver, adrenals, intestine, and testis, and undetectable in the eye (Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Influx Experiments. bPGT was transiently transfected in HeLa cells (Fig. 11, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The uptake rate of various PGs is significantly (P < 0.01) higher in bPGT-transfected cells compared with control. The affinity order of bPGT for different PGs is as follows: PGE2 (43.4 nM) = PGF2α (45.4 nM) ≥ PGD2 (52.9 nM) much greater than arachidonic acid (990 nM). The pattern of PG uptake is time dependent and biphasic. The influx rate by PGT-transfected cells peaks at 20 min, and then decreases and reaches the basal level at 160 min. The influx rate for PGE2, PGF2α, and PGD2 by bPGT is ≈20-fold higher compared with controls. 4,4′-Diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid and bromcresol green (anion transport inhibitors) inhibit the bPGT-mediated uptake of PGE2 and PGF2α in a dose-dependent manner. The level of inhibition is significantly higher at concentrations from 10–6/10–5 M (P < 0.05) to 10–4/10–3 M (P < 0.01).

Efflux Experiments. The bPGT-mediated efflux rate of PGE2 and PGF2α was studied in the presence and absence of trans substrate lactate (Fig. 12, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). [3H]PGE2 and [3H]PGF2α are rapidly effluxed from the cells during the first 10–20 min, leaving <30% of [3H]PGs loaded inside the cells. The efflux rate of PGE2 and PGF2α is increased ≈3-fold (P < 0.05) in bPGT-transfected cells in the presence of the trans substrate. The efflux rate is significantly (P < 0.05) decreased (≈3 fold) in the presence of 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (500 μM) and bromcresol green (50 μM).

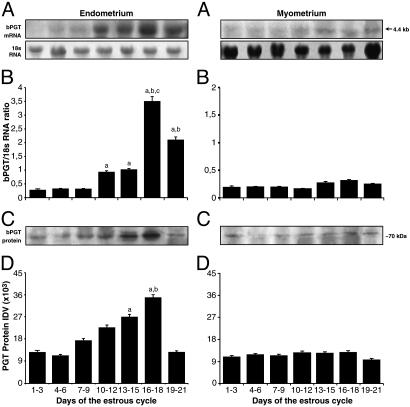

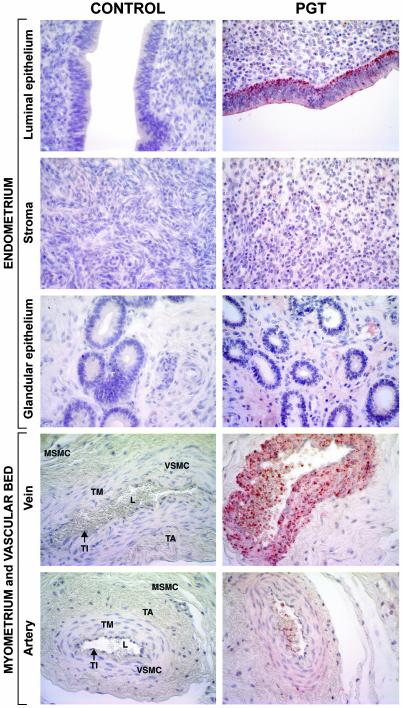

Expression of bPGT in Endometrium and Myometrium During the Estrous Cycle. bPGT mRNA and protein are expressed and modulated in endometrium and myometrium during the estrous cycle (Fig. 1). In endometrium, the level of bPGT mRNA is low between days 1 and 9, moderate between days 10–15 and 19–21 (P < 0.05), and maximum between days 16 and 18 (P < 0.01) of the estrous cycle. The level of bPGT protein expression is significantly (P < 0.05) higher between days 13 and 18 of the estrous cycle. In myometrium, PGT mRNA and protein are expressed uniformly at low levels throughout the estrous cycle. Immunohistochemical localization (Fig. 2) reveals that on day 16 of the estrous cycle, bPGT is strongly expressed in the basal region of the endometrial luminal epithelial cells, fairly expressed in endometrial stromal cells, poorly expressed in myometrial circular and longitudinal smooth muscle cells, and absent in glandular epithelium. In the myometrial vascular bed on day 16 of the estrous cycle, PGT protein is highly expressed in tunica intima and smooth cells of tunica media of uterine vein and diffusely expressed in tunica media of uterine artery. The level of expression is comparatively higher in veins than in arteries.

Fig. 1.

Expression of bPGT in endometrium and myometrium during the bovine estrous cycle. (A) Northern analysis. As an internal standard 18S RNA was used. (B) Densitometry analysis of bPGT mRNA. a, days 10–21 vs. others (P < 0.05); b, days 16–21 vs. others (P < 0.05); c, days 16–18 vs. others (P < 0.01). (C) Western analysis. (D) Densitometry analysis of bPGT protein. a, days 13–18 vs. others (P < 0.05); b, 16–18 vs. others (P < 0.05). Numerical values are presented as the mean ± SEM of three samples.

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical localization of bPGT in bovine uterus on day 16 of the estrous cycle (×400). PGT protein is highly expressed in basal region of luminal (L) epithelium, diffusely expressed in stromal cells, and absent in glandular epithelium of endometrium. PGT protein is diffusely and uniformly expressed in myometrial smooth muscle cells (MSMC). PGT protein is highly expressed in tunica intima (TI) and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) of tunica media (TM) of uterine vein compared with uterine artery and was absent in tunica adventitia (TA). Anti-bPGT (1:1,000) and goat anti-rabbit IgG biotinilated (1:200) were used as the primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. For negative control, preimmune rabbit serum (1:1,000) was used. Immunohistochemistry was performed by using a Vectastain Elite ABC kit (DAKO).

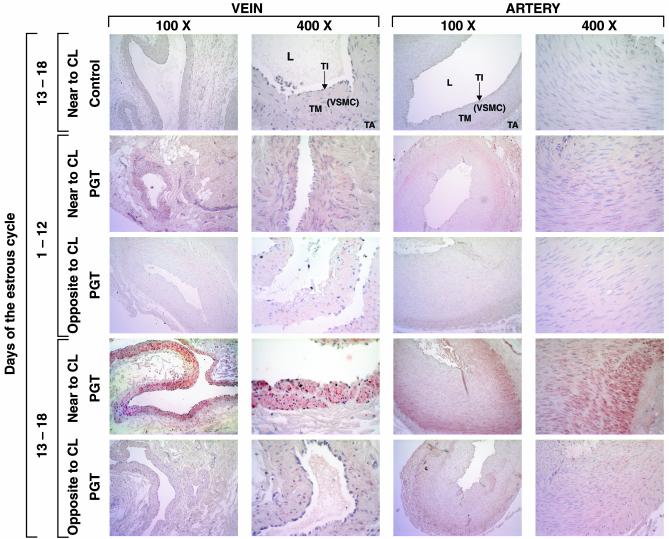

Expression of bPGT in UOP During the Estrous Cycle. Overall, bPGT mRNA and protein are expressed in UOP on both sides of the genital tract throughout the estrous cycle (Fig. 3). However, the level of PGT expression is significantly (P < 0.05) higher in UOP adjacent to the CL between days 13 and 18 of the estrous cycle. Immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4) reveals that PGT protein is expressed in tunica intima and smooth muscle cells of tunica media of uterine vein and in tunica media of ovarian artery but is absent in tunica adventitia, showing that PGT localization is selective and specific. In the uterine vein of UOP, PGT is localized in the entire layer of tunica media, toward as well as outward to the lumen. By contrast in ovarian artery, PGT is localized only in the outer layer of tunica media, not toward the lumen.

Fig. 3.

Expression of bPGT in UOP during the bovine estrous cycle. (A) Northern analysis. As an internal standard 18S RNA was used. (B) Densitometry analysis of bPGT mRNA. a, days 13–18 vs. others (P < 0.05). (C) Western analysis. (D) Densitometry analysis of bPGT protein. a, days 13–18 vs. others (P < 0.05). Numerical values are presented as the mean ± SEM of three samples.

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical localization of bPGT in UOP during the bovine estrous cycle (×400). PGT protein is expressed in tunica intima (TI) and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) of tunica media (TM) of uterine vein and in tunica media of ovarian artery but absent in tunica adventitia (TA). In uterine vein, PGT is localized in the entire layer of tunica media, toward as well as outward of the lumen. In ovarian artery, PGT is localized only in the outer layer of tunica media, not toward the lumen (L). Anti-bPGT (1:1,000) and goat anti-rabbit IgG biotinilated (1:200) were used as the primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. For negative control, preimmune rabbit serum (1:1,000) was used. Immunohistochemistry was performed by using a Vectastain Elite ABC kit.

Discussion

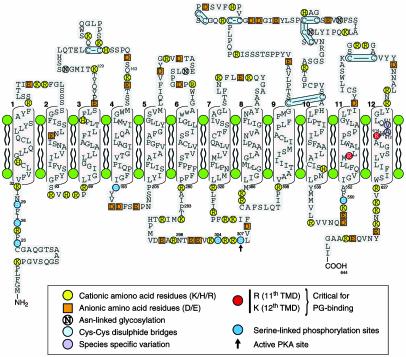

In the present study, we have cloned and characterized the function and expression of the bPGT [in line with the nomenclature already established for rat PGT as rPGT (23), we use bPGT]. bPGT exhibits a high percentage of homology with its human, mouse, and rat counterparts. Hydropathic analysis (29) of the predicted amino acid sequence of bPGT reveals the presence of 12 hydrophobic transmembrane domains characteristic of OATP and PGT molecules described in other species (20, 21). By analogy with previous reports in other species, hydropathic and structural analyses (Fig. 5) of bPGT suggest that Arg-561 and Lys-614 located in the 11th and 12th transmembrane domains, respectively are involved in ligand binding activity. In bPGT, from a total of 644 aa, 31 (4.8%) are negatively charged, 56 (8.6%) are positively charged, and the remaining 557 (86.4%) are neutral. Thus, the predominance of net positive charges makes the molecule cationic. Multiple serine phosphorylation sites for PKC are present in the cytoplasmic loops of bPGT. More details of the structural analyses of bPGT, comparison with other species, and the putative functions are discussed in Supporting Text.

Fig. 5.

Suggested transmembrane model (see Fig. 13, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for an enlarged format) of bPGT based on structural and hydropathic analyses of amino acid sequences. Numbers 1–12 indicate the 12 transmembrane domains. Different amino acid residues associated with structural and functional integrity of bPGT protein are indicated and highlighted by using different colors. Both amino and carboxyl termini are intracellular. Arg-561 and Lys-614 are located in the 11th and 12th transmembrane domains, respectively. Eight Cys-Cys zinc-finger motifs are observed in the extracellular loop. Four N-linked glycosylation sites are present in bPGT. Multiple serine phosphorylation sites for PKC are present in the cytoplasmic loops.

Despite the importance of PGs in the regulation of reproductive function, there is no report on the role of PGT in reproductive system of any species. bPGT is expressed in different tissues, including lungs and kidneys, where it was first reported in other species. Interestingly, bPGT is also expressed at a high level in different reproductive tissues. The role of PGT in PG metabolism and cellular transport has been described in kidney tubules (26), pulmonary epithelial cells (20), and human umbilical vein endothelial HUVEC cells (33). In bovine and ovine ≈65% and 99% of PGs, respectively, are metabolized in the pulmonary vascular bed after a single passage (8). The abundant expression of bPGT in bovine lung supports its role in PG metabolism, but its high expression in endometrium and CL suggests that it may play important roles in the regulation of reproductive function as well.

Before further investigating bPGT expression, we studied its ability to facilitate PG transport in HeLa cells, a model that was used to characterize the rPGT (32). The influx and efflux studies demonstrate that bPGT has a high affinity for PGE2, PGF2α, and PGD2 and extremely low affinity for arachidonic acid. bPGT transports PGE2 and PGF2α with almost similar affinity. In HeLa cells transfected with bPGT, the efflux rate of PGE2 and PGF2α is significantly higher in the presence of the trans substrate, lactate. Bromcresol green and 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid, two potent anion transport inhibitors, interfered with the transport of PGE2 and PGF2α in a dose-dependent manner. Thus, our results suggest that bPGT is a functional PGT and are in agreement with findings on rPGT (20, 21). The key principle behind the transport of PGs through rPGT is an obligatory exchange with lactate as the preferred antiporter (21, 34). It is well known that lactate is the by-product of the glycolytic pathway involved in the generation of ATP. It was found that PG uptake through rPGT varied with intracellular production of ATP (32). Altogether, these observations indicate that lactate acts as an important regulator of PGs transport across the cell membranes (21). It has been well established that in ruminants the utero-placental system produces and uses lactate (35). The human endometrium produces high levels of lactate during the preimplantation window (36). It has been recently reported in human that deficiency in lactate dehydrogenase, an enzyme responsible for the production of lactate, leads to the lack of uterine smooth muscle contraction and parturition failure (37). These studies together with the known effects of PGs in reproductive processes indirectly support a contribution of PGT.

PGT is expressed in bovine endometrium throughout the estrous cycle, but the level of expression is significantly higher between days 16 and 18 both at the mRNA and protein levels. Selective localization PGT at the basal region of the luminal epithelial cells suggests that PGF2α and PGE2 produced in the epithelial cells are transported toward the uterine compartment, but not to the uterine lumen, to effect luteolysis or establish the pregnancy. The diffused expression of PGT in stromal cells supports its role in the transport of endometrial PGs toward the vascular system and ovarian compartment and also suggests its role in autocrine and paracrine action of PGs in endometrial stroma. bPGT is expressed in myometrium uniformly at low levels throughout the estrous cycle and is diffusely localized in both inner circular and outer longitudinal smooth muscle cells. The expression of PGT in myometrial smooth muscle cells may contribute to the transport of PGE2 and PGF2α to bring forth uterine relaxation and/or contraction. In the bovine uterus, the vascular bed is located between the endometrial stroma and myometrial inner circular muscle layers. The vascular wall is composed of an inner tunica intima, a middle tunica media, and an outer tunica adventitia (17, 18). On day 16 of the estrous cycle, the high expression of PGT protein in tunica intima and media of uterine vein compared with artery suggests that PGT contributes to the drainage of PGs from uterine compartments.

Endometrial PGF2α and/or PGE2 are transferred from the uterine to the ovarian compartment through the UOP to bring forth their endocrine action, luteolysis, or luteostasis in ruminants. Anatomical studies of the UOP indicate that the ovarian artery is more convoluted and coiled around the uterine vein at this specialized site of PG transfer. The walls of the uterine vein and ovarian artery are thinner in the area of venous-arterial apposition. Moreover, the connective tissue bundles of the tunica adventitia in the area of apposition of the uterine vein and ovarian artery form a single stratum, thereby the demarcation between the two vessel is largely obliterated (17, 18). Normally, the transfer of PGs takes place in UOP adjacent to the CL to regress or rescue it. It has been proposed since the 1970s that simple diffusion (17) or counter current exchange (8, 9) could be the mechanisms involved in the transport of PGs across the UOP vascular wall. However, the exact underlying mechanism has not been determined until now. Because PGs diffuse poorly through plasma membranes (20, 21) a carrier-mediated transport mechanism is inevitable for the transport of PGs across the biological membranes. The high level of PGT mRNA and protein expression in UOP adjacent to the CL between days 16 and 18 of the estrous cycle coincides with the high production of endometrial PGs and the presence of high levels of PGs in the uterine venous effluent. Selective localization of PGT protein in the entire tunica intima and tunica media layers of uterine vein and in outer smooth muscle layers of tunica media of ovarian artery supports a role for PGT in compartmental transfer of PGs. Moreover, the anatomical structure of UOP and the associated selective expression of PGT further strengthen its role in the compartmental transport of PGs across the vascular wall. Taken together, our findings and available information indicate that PGT-mediated PG transport is the most likely mechanism involved in the compartmental transfer of PGs from uterine vein to ovarian artery in ruminants.

During the bovine estrous cycle, PGF2α production is maximal between days 15 and 17, whereas PGE2 production is higher during mid and late luteal phase of the estrous cycle (5, 8, 38). Days 15–17 are considered as the critical period for either luteolysis initiating a new estrous cycle or establishment of pregnancy. Recently, we have shown that the PG biosynthetic enzymes COX-2, PGES (12), and PGFS (13) and PG receptors EP2, EP3, EP4, and FP (15, 16) are highly expressed in the endometrium during late diestrus and proestrus of the bovine estrous cycle. In myometrium we have found the expression and regulation of relaxant EP2 and contractile FP receptors during the bovine estrous cycle (15, 16). Interestingly, the pattern of expression of PGT closely matches the pattern of expression of PG biosynthetic enzymes and receptors in bovine uterine tissues during the estrous cycle. Present results along with our previous findings and those of others converge to support a significant role of PGT in bovine endometrium and myometrium to effect the cellular transport of PGE2 and PGF2α to mediate autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine action at the time of luteolysis or establishment of pregnancy.

Higher expression of bPGT in both the endometrium and UOP on the same side as the ovary bearing the CL implies that a product of the CL, presumably progesterone, can locally control the expression of bPGT. Future studies are required to understand the dynamic regulation of PGT in the bovine reproductive system.

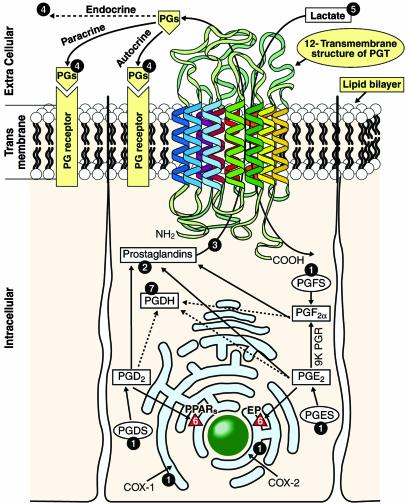

Based on these findings, and the previous data regarding the presence of PG biosynthetic enzymes and receptors in bovine uterus (12–16), and available information about PGT (20, 21), we propose an integrated model for cellular transport (influx and efflux), biosynthesis, and cell signaling in bovine uterus (Fig. 6). PG biosynthetic enzymes are located on the endoplasmic reticulum, nuclear membrane, or in the cytoplasm (39). Newly synthesized PGs cross the plasma membrane by facilitated carrier-mediated transport through bPGT to bring out their biological effects through cell surface receptors. After accomplishing biological functions, PGs are transported into cells for metabolism by cellular oxidation.

Fig. 6.

Proposed hypothetical model of PGT-mediated PGs transport in bovine uterus. 1, Sites of PG-biosynthetic enzymes. 2, Presence of PGs in the cytosol. 3, Transport of PGs across the plasma membrane through PGT. 4, Autocrine or paracrine or endocrine action of PGs on the membrane PG receptors. 5, Obligatory influx of lactate across the plasma membrane through PGT. 6, PG receptors in the nuclear membrane. 7, Cellular oxidation of PGs through catabolic enzyme. PGES, PGE synthase; PGFS, PGF synthase; PGDS, PGD synthase; PGDH, PG dehydrogenase; 9K PGR, 9-keto PG reductase; EP, PGE receptor; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Given the strategic role of PGs in the female reproductive system, improper transport and metabolism of uterine PGs should result in reproductive failures. Even though PG biosynthetic enzymes and receptors are essential for PGs biosynthesis and signaling, the trafficking of PGs across the cell membrane seems to be highly facilitated by PGT. Future studies on the regulatory factors involved in the expression of PGT mRNA and protein and complementary PGT knockout studies may give more information on the role of this novel molecule in mammalian reproductive processes. Collectively, the expression of bPGT in endometrium, myometrium, UOP, and the myometrial vascular bed suggests that PGT might have a significant role in cellular and compartmental transport of PGs in uterine tissues during the estrous cycle and the process of pregnancy recognition. In conclusion, bPGT was cloned and characterized. bPGT is expressed and regulated in endometrium, myometrium, and UOP during the estrous cycle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (to M.A.F.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: PG, prostaglandin; PGT, PG transporter; bPGT, bovine PGT; rPGT, rat PGT; UOP, utero-ovarian plexus; COX, cyclooxygenase; OATP, organic anion transporting polypeptide; CL, corpus luteum.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AY134618).

References

- 1.Smith, W. L., Garavito, R. M. & Dewitt, D. L. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33157–33160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narumiya, S., Sugimoto, Y. & Ushikuhi, F. (1999) Phys. Rev. 79, 1193–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi, T. & Narumiya, S. (2002) Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 68–69, 557–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya, M., Asselin, P., Hardy, P., Guerguerian, A. M., Shichi, H., Hou, X., Varma, D. R., Bouayad, A., Fouron, J. C., Clyman, R. I., et al. (1999) Circulation 100, 1751–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poyser, N. L. (1995) Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Essent. Fatty Acids 53, 147–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim, H., Paria, B. C., Das, S. K., Dinchuk, J. E., Langenbach, R., Askos, T. & Dey S. K. (1997) Cell 91, 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Challis, J. R., Sloboda, D. M., Alfaidy, N., Lye, S. J., Gibb, W., Patel, F. A., Whittle, W. L. & Newnham, J. P. (2002) Reproduction 124, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCracken, J. A., Custer, E. E. & Lamsa, J. C. (1999) Physiol. Rev. 79, 263–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCracken, J. A., Carlson, J. C., Glew, M. E., Goding, J. R., Baird, D. T., Green, K. & Samuelsson, B. (1972) Nat. New Biol. 238, 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pratt, B. R., Butcher, R. L. & Inskeep, E. K. (1979) J. Anim. Sci. 48, 1441–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magness, R. R., Huie, J. M., Hoyer, G. L., Huecksteadt, T. P., Reynolds, L. P., Seperich, G. J., Whysong, G. & Weems, C. W. (1981) Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Med. 6, 389–401. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arosh, J. A., Parent, J., Chapdelaine, P., Sirois, J. & Fortier, M. A. (2002) Biol. Reprod. 67, 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madore, E., Harvey, N., Parent, J., Chapdelaine, P., Arosh, J. A. & Fortier, M. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11205–11212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parent, M., Madore, E., Parent, J., Arosh, J. A., Chapdelaine, P. & Fortier, M. A. (2002) Annu. Proc. Endocr. Soc. 1, P2–407. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arosh, J. A., Banu, S. K., Chapdelaine, P., Emond, V., Kim, J., MacLaren, L. A. & Fortier, M. A. (2003) Endocrinology 144, 3076–3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arosh, J. A., Banu, S. K., Kimmins, S., Chapdelaine, P., MacLaren, L. A. & Fortier, M. A. (2002) Annu. Proc. Soc. Theriogenol. 1, 39. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginther, O. J. (1976) Vet. Scope 20, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ginther, O. J. (1981) Acta Vet. Scand. Suppl. l77, 103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazer, F. W. & Thatcher, W. W. (1977) Prostaglandins 14, 397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuster, V. L. (1998) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 60, 221–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuster, V. L. (2002) Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 68–69, 633–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehninger, A. L. (2000) Principles of Biochemistry (Worth, New York), pp. 389–566.

- 23.Kanai, N., Lu, R., Satriano, J. A., Bao, Y., Wolkoff, A. W. & Schuster, V. L. (1995) Science 268, 866–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu, R., Kanai, N., Bao, Y. & Schuster, V. L. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 98, 1142–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pucci, M. L., Bao, Y., Chan, B., Itoh, S., Lu, R., Copeland, N. G., Gilbert, D. J., Jenkins, N. A. & Schuster, V. L. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277, R734–R741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bao, Y., Pucci, M. L., Chan, B. S., Lu, R., Ito, S. & Schuster, V. L. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. 282, F1103–F1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapdelaine, P., Delahaye, S., Gauthier, E., Tremblay, R. R. & Dube, J. Y. (1993) BioTechniques 14, 163–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapdelaine, P., Vignola, K. & Fortier, M. A. (2001) BioTechniques 31, 478–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyte, J. & Doolittle, R. F. (1982) J. Mol. Biol. 157, 105–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennelly, P. J. & Krebs, E. G. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 15555–15558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chapdelaine, P., Moisset, P. A., Campeau, P., Asselin, I., Vilquin, J. T & Tremblay, J. P. (2000) Protein Eng. 13, 611–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan, B. S., Satriano, J. A., Pucci, M. & Schuster, V. L. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6689–6697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Topper, J, N., Cai, J., Stavrakis, G., Anderson, K. R., Woolf, E, A., Sampson, B. A., Schoen, F. J., Falb, D. & Gimbrone, M. A. (1998) Circulation 98, 2396–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan, B. S., Endo, S., Kanai, N. & Schuster, V. L. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. 282, F1097–F1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owens, J. A, Falconer, J. & Robinson, J. S. (1987) J. Dev. Physiol. 9, 225–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gardner, D, K., Lane, M. & Schoolcraft, W. B. (2002) J. Reprod. Immunol. 55, 85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anai, T., Urata, K., Tanaka, Y. & Miyakawa, L. (2002) J. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 28, 108–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyamoto, Y., Skarzynski, D. J. & Okuda, K. (2000) Biol. Reprod. 62, 1109–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urade, Y., Watanabe, K. & Hayaishi, O. (1995) J. Lipid Mediat. Cell Signal. 12, 257–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.