In 1995, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) established its Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group (PBM-SHG) to provide an integrated, comprehensive, portable, high-quality national drug plan for veterans. In the 12 years since then, PBM-SHG has matured into a pharmacy plan that has garnered national and international attention for maintaining a generous drug benefit at a very low cost. Indeed, the success of the VA’s pharmacy benefit plan has led many to suggest that it be a model for other integrated pharmacy plans, including Medicare Part D. The success of the VA prescription drug program has also been a concern for some, resulting in critical publications in the lay press, at times with misleading information. We describe the VA’s pharmacy benefit and outline some of the strategies that have helped the organization achieve a high-quality benefit while keeping pharmacy costs at a level that is almost certainly the lowest in the United States.

In addition to immunizations and other preventative health care measures, pharmaceuticals offer high value for improving the lives of Americans. In part because of the introduction of new drugs in recent years, the United States has experienced a remarkably steady increase in drug expenditures. From 1994 to 2006, the average annual price increase for prescriptions was 7.5%, compared with an annual average inflation rate of 2.6%. During this time, average retail prescription prices (generic and branded, all quantities) increased from $28.67 to $68.26, and average brand name drug prices increased from $32.23 to $111.02.1 A recent survey by Families USA reported that the average price (offered through Medicare Part D insurers) for the top 15 drugs prescribed to seniors increased by an average of 9.2% from 2006 to 2007.2

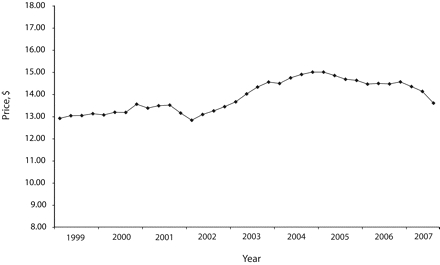

Despite the significant increases in drug expenditures in every other setting in the United States, drug costs in the VA have remained remarkably stable for more than 8 years. The average VA acquisition price for a 30-day supply of medication was $12.79 in October 1998 and $13.57 in May 2007; a total increase of less than 7% over more than 8 years, or less than 1% per year (Figure 1 ▶). Predictably, these trends have garnered the attention of both critics and supporters of the VA’s pharmacy program.

FIGURE 1—

Average 30-day prescription outpatient drug cost: Veterans Health Administration, October 1998–May 2007.

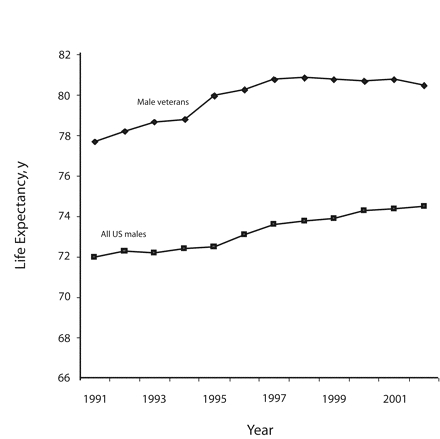

It is not our intention to address all our detractors and supporters, but it is illustrative to comment on a widely quoted and frequently referenced critique of the VA’s pharmacy benefit program to explore the depth of opposition to the VA’s evidence-based formulary process. Lichtenberg3 presents a figure that purports to show that VA patients’ life expectancies have declined since 1997 (the onset of the VA’s national formulary initiatives), whereas those of all US men have increased. The figure uses a different y-axis to depict longevity data for veterans than it does for all US men, dramatically distorting the graphical representation of the data. Figure 2 ▶ presents Lichtenberg’s data on the y-axis and shows a remarkably different picture.

FIGURE 2—

US veterans’ life expectancy versus life expectancy at birth for all US men, 1991–2002.

Source. Adapted from Lichtenberg.3

Lichtenberg’s report contains numerous methodological flaws and errors of fact and analysis, not the least of which is that the comparison cohort was all 23 million living US veterans, regardless of whether they received care from the VA or not, instead of using a cohort of the 6 million living veterans who have been VA patients. Lichtenberg lists drugs approved after 1997 that were not on the 2005 national formulary as evidence that the VA does not offer the newest drugs and, ostensibly, high-quality care. Incredibly, this list includes drugs that had already been voluntarily withdrawn from the US market for safety reasons. A much more detailed rebuttal of Lichtenberg’s paper is available.4

A complete description of the VA’s formulary management is available,5 although the VA has since moved to a unified national formulary; regional formularies no longer exist. The underlying principle serving as the backbone of the VA’s formulary management process is, first and foremost, an ongoing critical review of a medication’s scientific evidence. Contrary to the belief of some, when updating the formulary, the VA only considers drug costs after it has considered clinical efficacy, safety, relevance to the VA’s population, and role in therapy relative to other available medications. This strategy helps determine whether a drug should be added to the formulary, aids in the VA’s decision to identify preferred drugs in a drug class, develops prescribing criteria to ensure access to medically necessary drugs, promotes safe and cost-effective use, and identifies critical drug safety issues. The VA places high value on evidence demonstrating clinically relevant outcomes and much less value on intermediate health outcomes and community standards of care that evidence does not support.

Although at times critics have called this approach too conservative, we believe that it has served veterans well. For example, the VA created criteria for the cyclo-oxygenase selective inhibitor (COX-2) drugs that restricted their use to patients who required anti-inflammatory medications and who were at high risk for adverse gastrointestinal events. As a result, the VA’s use of COX-2 drugs was very different from that of Medicaid cohorts (COX-2 drugs accounted for approximately 5% of all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the VA compared with more than 50% in some Medicaid cohorts) when rofecoxib (Vioxx) was voluntarily withdrawn from the market in 2004 because of safety concerns. Likewise, because of safety concerns, the VA did not place the lipid-lowering drug cerivastatin (Baycol) on its formulary, unlike the Department of Defense, opting for the more expensive simvastatin (Zocor). Cerivastatin was later removed from the market because of problems with rhabdomyolysis.

The VA has several important tools to help manage the pharmacy benefit at the local, regional, and national levels, including the computerized medical record database and the national database of outpatient prescriptions. These tools facilitate the identification of drug safety issues and pharmacy utilization trends and serve as a basis for drug contract negotiations. For example, several years ago the VA identified all of its users of short-acting nifedipine for hypertension and arranged for their prescriptions to be changed to safer medications. More recently, the VA identified all elderly patients with renal insufficiency taking glyburide and is now intervening to change them to non–renally cleared agents.

The VA employs its own clinicians who are more likely than are private physicians to be willing participants in our formulary management programs. Equally important, it is likely that they are familiar with our formulary, particularly if they are employed full-time by the VA, thereby enhancing the probability that preferred formulary agents will be prescribed and national VA formulary policies will be followed. Because there are such significant differences in cost among drugs where national contracts for preferred drugs in a particular drug class exist in the VA, it is important that the VA consistently follow these contracts except in clinical scenarios that dictate otherwise.

The VA uses generic drug substitutions whenever US Food and Drug Administration–approved generic medications are available. Likewise, the VA evaluates drug classes with evidence reviews to determine which pharmaceuticals provide the “best value.” At times these best value drugs may not be the least expensive, but because they are the most efficacious or give a combination of efficacy and safety, they become preferred drugs on the VA formulary. Obviously, the ideal scenario is for a drug to be safe, effective, and inexpensive. Because the VA is able to track medication use and has a closed system, it is able to encourage the use of evidence-based therapies such as thiazide diuretics for uncomplicated hypertension. In this scenario, these preferred drugs offer not only proven efficacy and outcomes but also affordability.

The VA benefits from favorable drug pricing, as do other federal purchasers, through the federal supply schedule. In addition, the VA occasionally achieves deep discounts on individual drugs in selected drug classes through the national standardization contracting process where preferred drugs are added to the VA formulary. It is this area that has been the subject of concern for some in the pharmaceutical industry, the lay press, and politics, despite the fact that the VA has exercised relatively few standardization contracts over the years. In these contracts, the cost differences can be substantial for even just a few drugs because of the volume of drugs dispensed and the size of the discount. For example, Families USA compared the best Medicare Part D price of 40 mg of simvastatin (Zocor; ($1485.96/year) in 2006 to the VA’s price under a national contract ($191.16/year), for a savings of more than 87% ($1294.80/year). It is unclear what the VA’s price would have been without the contract—certainly less than the Medicare price—but given the sheer volume of Zocor prescribed to VA patients (more than 1.7 million patients in 2006), one can get an idea of the magnitude of the expenditures at stake with these negotiations. It should come as no surprise that pundits from all angles of the pharmaceutical access debate have tremendous interest in this single issue.

We believe that the VA can serve as a model for a national drug benefit administered by a federal agency with a commitment to provide a comprehensive, high-quality plan. This program is provided at costs unparalleled by any other federal or nonfederal group in the United States. Although some of the VA’s successful strategies may not be applicable to other agencies, the VA’s pharmacy benefit may offer lessons in the health care debate for expanding the provision of pharmaceutical care for the elderly and underinsured in our nation.

Contributors C. B. Good conceptualized the editorial and wrote the initial drafts. M. Valentino conceptualized the editorial, provided the drug pricing and utilization data, and wrote the initial drafts.

References

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation. Prescription drug trends, May 2007. Available at: http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/upload/3057_06.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2007.

- 2.Families USA. Medicare Part D Prices are Climbing Quickly. Available at: http://www.familiesusa.org/assets/pdfs/medicare-part-d-drug-prices.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2007.

- 3.Lichtenberg FR. Older Drugs, Shorter Lives? An Examination of the Health Effects of the Veterans Health Administration Formulary. New York, NY: Manhattan Institute for Policy Research; 2005. Medical Progress Report No. 2. Available at: http://www.manhattan-in-stitute.org/pdf/mpr_02.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2007.

- 4.Valentino MA. Overview of the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Health Care Group (PBM). Presented at: American Enterprise Institute: Can government price negotiation work for the Medicare drug benefit? January 19, 2007; Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.kaisernetwork.org/health_cast/uploaded_files/Valentino.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2007.

- 5.Sales MM, Cunningham FE, Glassman PA, Valentino MA, Good CB. Pharmacy benefits management in the Veterans Health Administration: 1995 to 2003. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11: 104–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]