Abstract

Mutants in the PRT1 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana are impaired in the degradation of a normally short-lived intracellular protein that contains a destabilizing N-terminal residue. Proteins bearing such residues are the substrates of an ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system called the N-end rule pathway. The chromosomal position of PRT1 was determined, and the PRT1 gene was isolated by map-based cloning. The 45-kDa PRT1 protein contains two RING finger domains and one ZZ domain. No other proteins in databases match these characteristics of PRT1. There is, however, a weak similarity to Rad18p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The RING finger domains have been found in a number of other proteins that are involved in ubiquitin conjugation, consistent with the proposed role of PRT1 in the plant N-end rule pathway.

The N-end rule pathway of protein degradation has been studied in Escherichia coli, yeast, mammalian cells, and plants (1, 2). The name of this pathway emphasizes the importance of the N-terminal amino acid residue for the metabolic stability of a cytoplasmic protein. Specifically, large or charge-carrying N-terminal residues function as degradation signals recognized by the N-end rule pathway. A remarkable aspect of this pathway is that protein features recognized as degradation signals are conserved in evolution, whereas components instrumental in its implementation are much less so. For instance, in eukaryotes the N-end rule is a part of the ubiquitin/proteasome system (3, 4), but prokaryotes, which lack ubiquitin, also have a distinct version of the N-end rule pathway (1).

Some of the components of the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway have been characterized in plants (5). It is therefore reasonable to assume that proteolysis by the N-end rule degradation in plants also is mediated by ubiquitin conjugation to substrate proteins, followed by degradation by the proteasome. We have been studying the N-end rule pathway in the model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana. Mutants were generated with the help of a reporter transgene (2). One locus, PRT1 (proteolysis 1), was found to be essential for the N-end rule pathway, because mutant plants do not degrade the model substrate, a transgenic dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) protein bearing a destabilizing N-terminal residue and other components of the complete degradation signal, called N-degron (1, 6). We have cloned the PRT1 gene through a strategy based on chromosomal mapping and found that it does not resemble any of the components of the well-characterized S. cerevisiae N-end rule pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains, Plant Lines, Material.

E. coli strain DH5α was used for cloning experiments. Agrobacterium strain C58C1 pCV2260 was obtained from D. Staiger (Eidgenōssische Technische Hochschule, Zurich, Switzerland). prt1 mutants are in Columbia (G. Rédei via C. Koncz, Max-Planck-Institut f. Zūchtungsforschung, Cologne, Germany) genetic background. Marker line W7 in the Ler background was obtained from M. Koornneef (via C. Koncz). Transgenic lines used in Fig. 1 (lanes 5–8) have been described (2). Transgenic line of Fig. 1 (lanes 3 and 4) expresses DHFR with an extension bearing an N-terminal phenylalanine residue (F-DHFR) under control of the CaMV 35S promoter, transformed into the plants as an insert in vector pΔHV (7). The line used for Fig. 1 (lanes 1 and 2) contains a transgene identical to that of lanes 3 and 4, except that TTT (Phe), the first codon of mature F-DHFR, is replaced by ATG (Met). A genomic λ library of Col-0 DNA was a gift from C. Koncz. A binary plasmid library of Ler DNA was a gift of E. Grill (Technische Universität, Munich, Germany). The λ gt10 cDNA library has been described (8). Cosmids from the vicinity of ABI3 have been described (9) and were obtained from J. Giraudat and J. Leung (Institut de Sciences Végétales, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Gif-sur-Yvette, France). Yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) clones were obtained from the Cologne stock center and from J. Leung. Contrary to published data (10), YAC clone EW 23C4 does not map to the PRT1/ABI3 region. Other restriction fragment length polymorphism marker clones were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Ohio State University, Columbus). Enzymes were purchased from Amersham, New England Biolabs, or Boehringer Mannheim and used according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. clasto-Lactacystin β-lactone was purchased from Boston Biochem (Cambridge). Analysis of DNA and protein sequences was carried out by using the GCG software package (Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI). Database searches were made by using programs of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (11, 12).

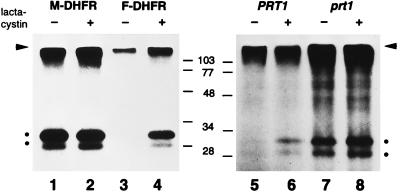

Figure 1.

F-DHFR is an N-end rule substrate that accumulates in prt1 mutant cells. Leaf material of transgenic plants was incubated with radioactive methionine in the presence (even lanes) or the absence (odd lanes) of clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (lactacystin), a specific inhibitor of the proteasome. Proteins were extracted, and DHFR was isolated by immunoprecipitation and detected by SDS/PAGE and fluorography. The level of M-DHFR (DHFR with an extension bearing an N-terminal methionine residue) is not increased by lactacystin (lanes 1 vs. 2), whereas F-DHFR increases considerably (lanes 3 vs. 4). Lanes 5 and 6 are the same as lanes 3 and 4, but transgene is expressed from the weaker nopaline synthase promoter. Lanes 7 and 8 are the same as lanes 5 and 6, but plant has a mutation in the PRT1 gene, which results in metabolic stabilization of F-DHFR. The arrowhead marks the origin of the separation gel, two dots indicate DHFR protein bands, the lower one being either a conformer or a cleavage product. Positions of molecular weight marker bands are indicated in the middle.

Genetic and Molecular Biology Techniques.

Genetic analysis was carried out according to refs. 13 and 14. For calculation of genetic distances, the formulae of Allard (15) were used. Standard procedures were used for chromosome walking, recombinant library screening, and cloning experiments (16–18). Sequencing was carried out by a commercial supplier (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). Both the cDNA and the genomic PRT1 region were sequenced on both strands. To identify mutations in prt1–1 and prt1–4, reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) products derived from the respective mRNAs were sequenced directly by MWG. To confirm the identified mutations, the prt1–4 RT-PCR product was subcloned and the relevant region was sequenced manually (Pharmacia sequencing kit). For prt1–1, PCR primers TCCAAAACAAGATCAATCTG/A, respectively, and TCTCTTGCGATAACAATGGCC, were used for allele-specific PCR (primer annealing temperature 62°C).

Protein Labeling and Detection.

Protein labeling and detection was carried out as described (2), with the following modifications: 200 μCi of 35S-Met were used per lane. During extract preparation, 20 μg/ml of pepstatin and Complete Mini protease inhibitor mix (Boehringer Mannheim; 1 pill per 7-ml buffer) was added. After extraction, soluble proteins were precipitated by addition of trichloroacetic acid to 15% (30 min at 0°C) and subsequent centrifugation, washed three times with acetone, and resolubilized in extraction buffer. To isolate antibody-antigen complexes, Dyna-beads (sheep anti-rabbit IgG; Dynal, Hamburg, Germany) were used. In cases indicated, lactacystin was included at 1 μg/ml during incubation of leaf material. For pulse–chase experiments, leaf pieces were labeled for 2 hr, washed, and further incubated in medium containing 20 mM methionine and 50 mM cycloheximide during the chase period.

Complementation Assays.

Binary cosmid clones spanning the region of interest were transferred into Agrobacterium and used for root transformation essentially as described (19) by using roots from prt1 plants. A part of the callus material was transferred to root-inducing medium [agar medium (2) supplemented with 0.1 mg/liter of benzyl-aminopurine, 1 mg/liter of 1-naphthyl-acetic acid, and 0.5 mg/liter of indole butyric acid] containing 0.1 mg/liter of methotrexate (MTX). Wild-type calli do not make roots and die, whereas prt1 mutant callus material grows and forms roots. Seeds from regenerated plants were germinated on agar medium containing 0.1 mg/liter of MTX to confirm the callus phenotype.

RESULTS

F-DHFR, a Substrate of the N-end Rule Pathway in Arabidopsis, Is Stabilized in the prt1 Mutant.

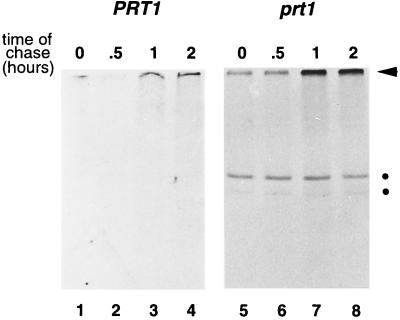

We previously have shown that mutants in the PRT1 gene accumulate F-DHFR, a transgenic DHFR fusion protein carrying the destabilizing N-terminal phenylalanine (F, or Phe) residue and other elements of the N-degron, a degradation signal recognized by the N-end rule pathway (2). In the presence of a specific inhibitor of the proteasome, clasto-lactacystin β-lactone, F-DHFR accumulates in wild-type Arabidopsis cells at least 4-fold over a control incubation lacking the inhibitor (Fig. 1, lane 3 vs. 4). In contrast, M-DHFR, a protein identical to F-DHFR except for the first amino acid (which is Met instead of Phe), does not accumulate to a higher extent in the presence of the inhibitor (Fig. 1, lanes 1 vs. 2). Thus, lactacystin specifically affects the accumulation of F-DHFR. Although we cannot rule out an indirect effect, a straightforward interpretation of the data is that F-DHFR is in planta rapidly degraded by a proteasome-dependent pathway. The degradation of F-DHFR depends on the nature of its N-terminal residue, thus defining the presence of the N-end rule pathway in plants. In contrast, in the prt1 mutant, F-DHFR can easily be detected, and lactacystin does not cause any further enrichment of F-DHFR (Fig. 1, lanes 7 and 8). Pulse–chase experiments were carried out to directly demonstrate that F-DHFR is metabolically stable in prt1 mutants. Fig. 2 shows such an experiment using either wild-type (PRT1) leaf material (lanes 1–4) or mutant (prt1) leaves (lanes 5–8). Although F-DHFR is below the level of detection in the wild type, its presence, as well as its metabolic stability during a 2-hr chase period, are demonstrated in prt1 cells.

Figure 2.

F-DHFR is metabolically stable in prt1 mutant cells. Leaf material was labeled for 2 hr, washed, and further incubated in medium containing nonradioactive methionine and translation inhibitor. Samples were withdrawn at the indicated times and processed as in Fig. 1. Lanes 1–4, leaf material was taken from wild-type plants. Lanes 5–8, leaf material from prt1 mutant plants was used. Dots indicate DHFR bands. The arrowhead indicates the origin of the separation gel.

Positional Cloning of PRT1.

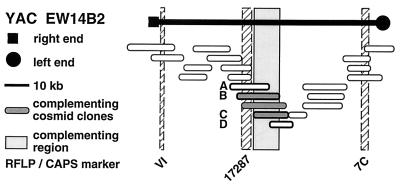

We have mapped the PRT1 gene by crosses to marker lines in the Landsberg background. We found genetic linkage to the gl1, and, more weakly, to the hy2 locus on chromosome III of A. thaliana. A gl1 prt1 double mutant and a hy2 prt1 mutant were crossed to wild-type plants transgenic for the F-DHFR transgene. The results placed PRT1 in proximity to ABI3. A cross of gl1 prt1 plants to abi3 hy2 plants indicated a genetic distance of 0.14 cM between abi3 and prt1 and showed that the order of markers is HY2-ABI3-PRT1-GL1. Table 1 shows the segregation data and the derived genetic distances. Together with previous work on ABI3 in other laboratories, this result defined the direction of a potential genomic walk (9). YAC clones were isolated that potentially span the region of interest. Table 2 summarizes the YAC clones used. To facilitate analysis of crossover points between gl1 and prt1, published and novel markers were converted into cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) markers. Table 3 lists oligonucleotides, fragment size, and enzymes used. Among 60 plants with a recombination event between gl1 and prt1, one was found by CAPS analysis to have a crossover point between markers VI and 17287. These data identified the end point of the walk. Thus, based on genetic data, YAC clone EW 14B2 contains the PRT1 gene. Cosmid clones that span YAC EW 14B2 were isolated from a library of binary vectors. Fig. 3 shows the clones obtained, together with additional information.

Table 1.

Mapping of PRT1

| Parent genotype | Segregant genotype | Number of segregants | Genetic distance, map units |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

27 | |

| 21.5 ± 7 | |||

|

47 | ||

|

|

98 | |

| 40 ± 5 | |||

|

122 | ||

|

|

371 | |

| 0.14 ± 0.14 | |||

|

1 | ||

The abi3/ABI3 genotype of these segregants was determined by analysis of F3 families.

Table 2.

YAC clones that map to the region of PRT1

| Designation | Hybridizing markers | Approximate size, kb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| EW 14B2 | 7C of 4711*; 17287 | 120 | This study |

| CIC XII 6 | 4711; 17287 | 420 | J. Leung; 33 |

| CIC XI 9 | 4711; 17287 | 650 | J. Leung; 33 |

kb, kilobases.

Cosmid clone 4711 contains two restriction fragment length polymorphism markers (9), one of which is contained in EW 14B2.

Table 3.

Cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) markers proximal to PRT1

| Name | Oligo sequences | Fragment size, kb | Enzyme used to cut fragment* |

|---|---|---|---|

| VI | GGGTTTATAGAGGTTGCTTCT ATCTTATTAGCCGCAATGTCC | 0.7 | DraI |

| 17287 | ACTAGTACTAAATTCACATGA GGGAGATGAAGATAATGGAATGA | 1.5 | HindIII |

kb, kilobases.

The restriction enzyme indicated detects a fragment length polymorphism between La-er and Col-0 DNA.

Figure 3.

Isolation of A. thaliana PRT1 by positional cloning. YAC clone EW 14B2 was isolated and shown to contain PRT1 by analysis of recombination points (see Table 1 and text). The left end of EW 14B2 is close to ABI3 of A. thaliana chromosome 3. For restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) markers, see also Table 3. All cosmid clones were tested in a callus assay. Clones A-D also were analyzed in transgenic plants (see Fig. 4).

Complementation of the prt1 Mutation.

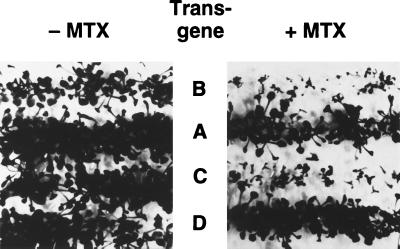

The overlapping cosmid clones that span YAC EW 14B2 were used for transformation of prt1 mutant plants. Three overlapping clones reverted the MTX-resistant state of prt1 mutants to the MTX-sensitive state of the wild type (Fig. 3). Fig. 4 shows complementation of regenerated plants by clones B and C, restoring the sensitivity to MTX observed in wild-type plants. Neighboring clones A and D, on the other hand, did not complement.

Figure 4.

Cosmid clones carrying PRT1 restore the MTX-sensitive phenotype of wild-type plants. prt1 mutant plants were transformed with binary cosmid clones A-D (see Fig. 2). Transgenic seeds were sown in files on plates either containing (Right) or lacking (Left) 0.1 mg/ml of MTX. Like wild-type seedlings (2), prt1 seedlings with transgenes B or C do not grow in presence of MTX.

Sequence Analysis of the PRT1 Gene.

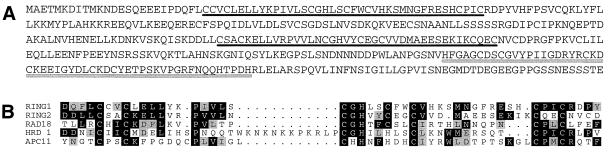

Because the complementing cosmid clones were made from Ler DNA, we isolated λ clones of the complementing region derived from Col-0 DNA. This additional step facilitated subsequent comparison of wild-type and mutant sequences (which were generated in the Col-0 background; see below). An approximate 9-kilobase region was sequenced (GenBank accession no. AJ224306). It contains two distinct ORFs, one of which however, is contained in its entirety in a noncomplementing cosmid clone (clone D of Figs. 3 and 4). The other one therefore was a candidate for PRT1. An apparently full-length cDNA clone to this ORF was isolated and sequenced (GenBank accession no. AJ224307). PRT1 has seven introns and codes for 410 amino acids. DNA gel blot experiments suggest that PRT1 is a single-copy gene in Arabidopsis (data not shown). Fig. 5A shows the conceptual translation product. A search for known amino acid motifs indicates that PRT1 contains three easily identifiable domains. All of them have the potential to bind two Zn2+ ions via Cys and His residues. Two are so-called RING fingers (20), the third is a ZZ domain (21). The simultaneous presence of these domains in one protein is apparently unique.

Figure 5.

(A) Sequence of the PRT1 protein. Underlined in black, two RING finger domains; underlined in gray, ZZ domain. (B) Alignment of RING finger domains of several proteins with potential function in ubiquitin conjugation. RING 1, 2: RING finger domains of PRT1. RAD18, HRD1, APC11: RING finger domains of yeast proteins Rad18p, Hrd1p, and Apc11p, respectively. To optimize alignment, a maximum of three gaps were allowed per sequence (indicated by dots).

Mutant Alleles of PRT1.

To confirm the correct identification of the PRT1 gene, nucleotide changes in prt1 mutants were analyzed. RNA gel blot experiments indicated that all four alleles available did produce an mRNA of normal size and abundance (data not shown). Two alleles, prt1–1 and prt1–4, were chosen for further analysis. Reverse transcription–PCR and sequencing of PCR products indicated that prt1–1 has a C to T transition at position 452 of the cDNA, converting Gln-111 (CAG) into a stop codon. Likewise, a 1-bp deletion in prt1–4 (position 212 of the cDNA) causes a frameshift.

Comparison of PRT1 to Other Proteins.

A blast search (12) for similar sequences yielded several animal and plant cDNA fragments (expressed sequence tag clones; data not shown). Similarity is most pronounced to the RING finger and ZZ domains (Fig. 5A). The most similar protein in the yeast genome is Rad18p, a DNA repair enzyme. This was surprising, because Rad18p is not a component of the N-end rule pathway. It remains to be seen whether this similarity is of functional relevance. Interestingly, Rad18p is capable of forming a complex with the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Rad6p/Ubc2p, which is an essential component of the N-end rule pathway (22, 23). RING finger domains of Rad18p, as well as of Apc11p and Hrd1p, two other proteins potentially involved in ubiquitin conjugation (24, 25), are listed in Fig. 5B. The similarity to PRT1, however, is more limited in these latter two cases. In particular, one of the Cys residues of the RING finger motif is replaced by His, indicating that they belong to a different subclass of RING finger proteins.

DISCUSSION

We have shown previously that mutations in the PRT1 gene of A. thaliana lead to metabolic stabilization of a transgenic protein bearing the N-degron, a degradation signal recognized by the N-end rule pathway (2). In this work, we demonstrate that the transgenic model substrate, F-DHFR, is indeed degraded by the N-end rule pathway of plants (Figs. 1 and 2) and characterize the PRT1 gene after its isolation by map-based cloning (Figs. 3 and 4). prt1 mutants do not show increased sensitivity toward higher temperatures, amino acid analogs, or heavy metals (T.P. and A.B., unpublished data). This finding suggests that mutations in PRT1 do not interfere with the known function of the ubiquitin system in the proteolysis of aberrant proteins. The prt1 mutation therefore may specifically affect the N-end rule pathway. At the same time, PRT1 has no obvious sequence similarity to any component of the well-characterized yeast N-end rule pathway.

The PRT1 protein has two so-called RING fingers (20) and one ZZ domain (21). Both structures are believed to contain Zn2+ ions and probably are involved in protein–protein interactions. The similarity of the RING fingers of PRT1 to each other (Fig. 5B) suggests that they may have arisen by a duplication event. A protein of S. cerevisiae with some similarity to PRT1 is the DNA repair enzyme Rad18p. It may be noteworthy that one part of Rad18p, the CCHC motif (26, 27), which has been implicated in binding of single-strand DNA, is not conserved between Rad18p and PRT1. It is therefore unlikely that PRT1 is a direct functional homolog of the DNA repair component Rad18p. However, Rad18p can form a stable complex with S. cerevisiae Ubc2p (Rad6p), a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that is essential for both DNA repair, and the N-end rule pathway (22, 23, 26). Therefore, experiments currently under way shall determine whether PRT1 protein interacts with one of the Ubc2p homologs of A. thaliana (8, 28). Interestingly, a number of additional proteins with potential or proven roles in ubiquitin conjugation do contain a RING finger domain: Apc11p and Hrd1p of S. cerevisiae (24, 25) and mUBR1, the mouse E3α (Y. T. Kwon and A. Varshavsky, personal communication). Thus, RING finger domains may interact with other subunits of an E3 complex, or they may bind directly to substrate proteins.

Although the available data do not rule out the possibility that PRT1 functions in regulation of the N-end rule pathway, the results are consistent with the hypothesis that PRT1 is a component of a ubiquitin-protein ligase (E3). If this is true, the plant N-end rule pathway uses a ligase that is distinct from its counterparts in yeast (29) and mammalian cells (Y.T. Kwon and A. Varshavsky, personal communication). An E3 function for PRT1 would be consistent with the notion that ubiquitin-protein ligases are the most diverse components of the ubiquitin system. For instance, there is at best limited sequence similarity between four types of the previously characterized E3 enzymes, UBR1, E6AP, Skp1p/Cullin/F-box ubiquitin ligase complex (SCF), and Anaphase-promoting complex (APC) (24, 29–32). Thus, plant PRT1 may be a novel subunit of a known E3 ligase, or it may belong to yet another class of ubiquitin-protein ligases.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. E. Grill (Technische Universität, Munich, Germany) for the binary cosmid library used in this study, to Drs. J. Giraudat and J. Leung (Institut de Sciences Végétales, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Grif-sur-Yvette, France) for YAC and cosmid clones from the vicinity of ABI3 and for abi3 mutant lines, to Drs. A. Varshavsky and Y.T. Kwon (California Institute of Technology) for providing unpublished data, and to Drs. D. Schweizer, C. Grimm and A. Varshavsky for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung (Grants S 6010 and P 11616).

ABBREVIATIONS

- DHFR

dihydrofolate reductase

- F-DHFR

DHFR with an extension bearing an N-terminal phenylalanine residue

- MTX

methotrexate

- YAC

yeast artificial chromosome

Footnotes

References

- 1.Varshavsky A. Genes Cells. 1997;2:13–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1020301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmair A, Becker F, Schell J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:418–421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochstrasser M. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:405–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas A L, Siepman T J. FASEB J. 1997;11:1257–1268. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.14.9409544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vierstra R D. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:275–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00039386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachmair A, Varshavsky A. Cell. 1989;56:1019–1032. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90635-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachmair A, Becker F, Masterson R V, Schell J. EMBO J. 1990;9:4543–4549. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zwirn P, Stary S, Luschnig C, Bachmair A. Curr Genet. 1997;32:309–314. doi: 10.1007/s002940050282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giraudat J, Hauge B M, Valon C, Smalle J, Parcy F, Goodman H. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1251–1261. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang I, Kohchi T, Hauge B M, Goodman H M, Schmidt R, Cnops G, Dean C, Gibson S, Iba K, Lemieux B, et al. Plant J. 1991;1:367–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1991.t01-5-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benson D A, Boguski M S, Lipman D J, Ostell J, Ouellette B F F. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rédei G P, Koncz C. In: Methods in Arabidopsis Research. Koncz C, Chua N-H, Schell J, editors. Singapore: World Scientific; 1992. pp. 16–82. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koornneef M, Stam P. In: Methods in Arabidopsis Research. Koncz C, Chua N-H, Schell J, editors. Singapore: World Scientific; 1992. pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allard R W. Hilgardia. 1956;24:235–278. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R F, Moore D O, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koncz C, Chua N-H, Schell J. Methods in Arabidopsis Research. Singapore: World Scientific; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung J, Giraudat J. In: Arabidopsis Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology. Martinez-Zapater J M, Salinas J, editors. Vol. 82. Totowa, NJ: Humana; 1998. pp. 277–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valvekens D, van Montagu M, van Lijsebettens M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5536–5540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saurin A J, Borden K L B, Boddy M N, Freemont P S. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:208–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponting C P, Blake D J, Davies K E, Kendrick-Jones J, Winder S J. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dohmen R J, Madura K, Bartel B, Varshavsky A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7351–7355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sung P, Berleth E, Pickart C, Prakash S, Prakash L. EMBO J. 1991;10:2187–2193. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zachariae W, Shevchenko A, Andrews P D, Ciosk R, Galova M, Stark M J R, Mann M, Nasmyth K. Science. 1998;279:1216–1219. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hampton R Y, Gardner R G, Rine J. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:2029–2044. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.12.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailly V, Prakash S, Prakash L. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4536–4543. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailly V, Lauder S, Prakash S, Prakash L. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23360–23365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan M L, Carpenter T B, Vierstra R D. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;24:651–661. doi: 10.1007/BF00023561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartel B, Wünning I, Varshavsky A. EMBO J. 1990;9:3179–3189. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07516.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheffner M, Huibregtse J M, Vierstra R D, Howley P M. Cell. 1993;75:495–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feldman R M R, Correll C C, Kaplan K B, Deshaies R J. Cell. 1997;91:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu H, Peters J-M, King R W, Page A M, Hieter P, Kirschner M W. Science. 1998;279:1219–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5354.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Creusot F, Fouilloux E, Dron M, Lafleuriel J, Picard G, Billaut A, Le Paslier D, Cohen D, Chabouté M-E, Durr A, et al. Plant J. 1996;8:763–770. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08050763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]