Abstract

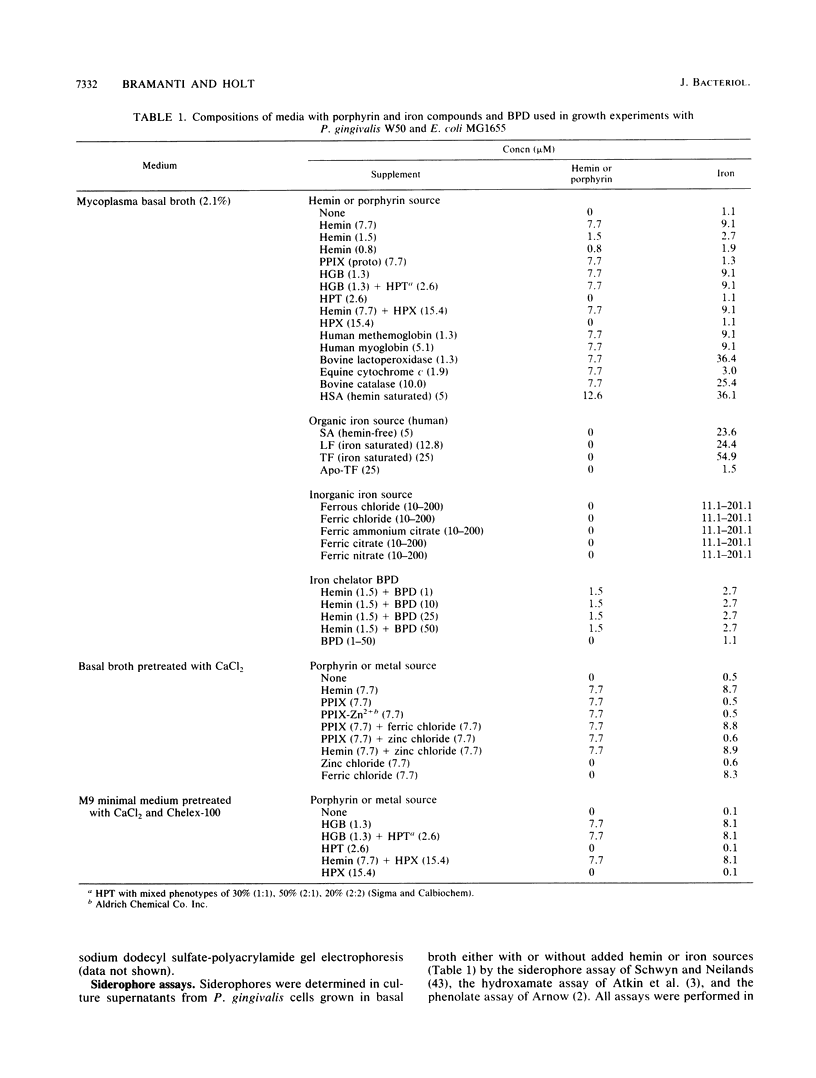

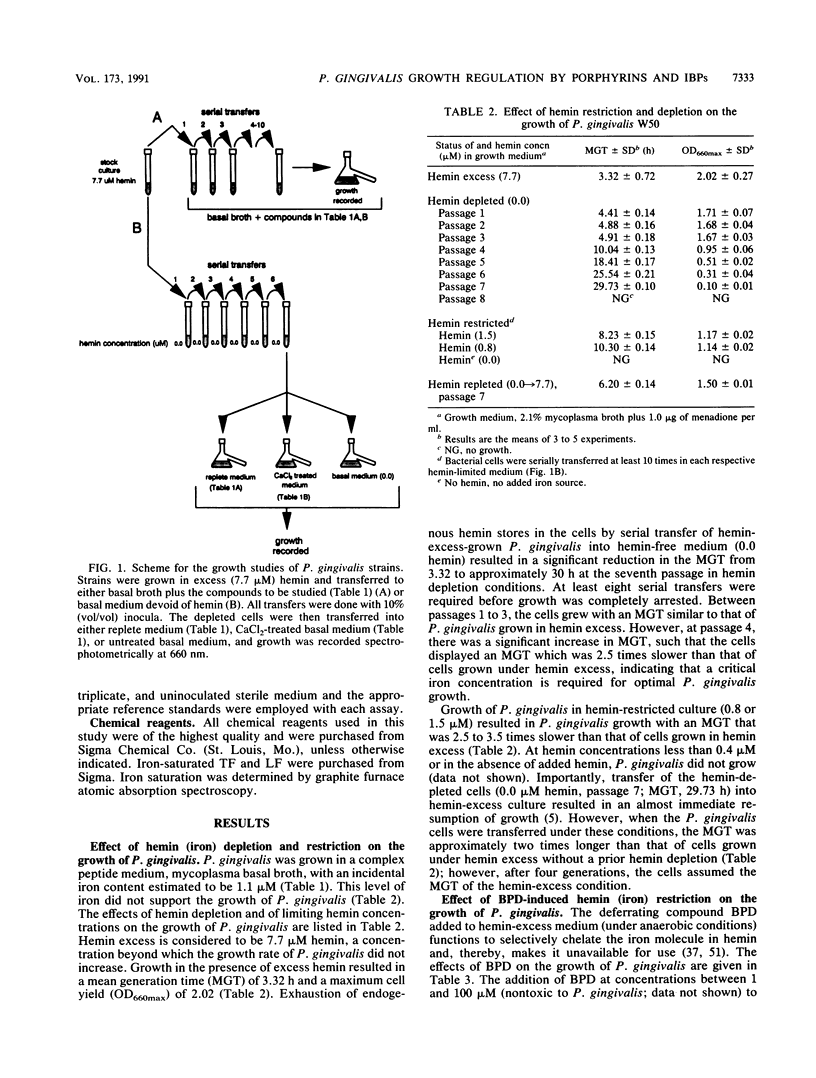

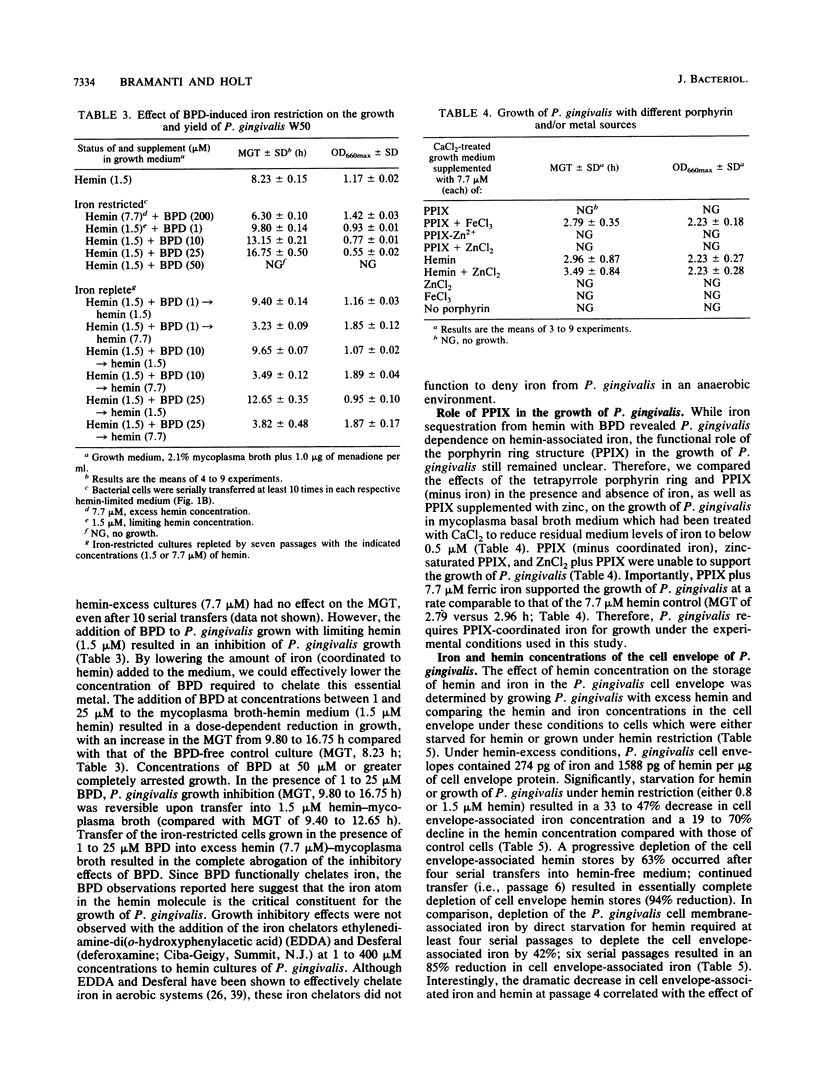

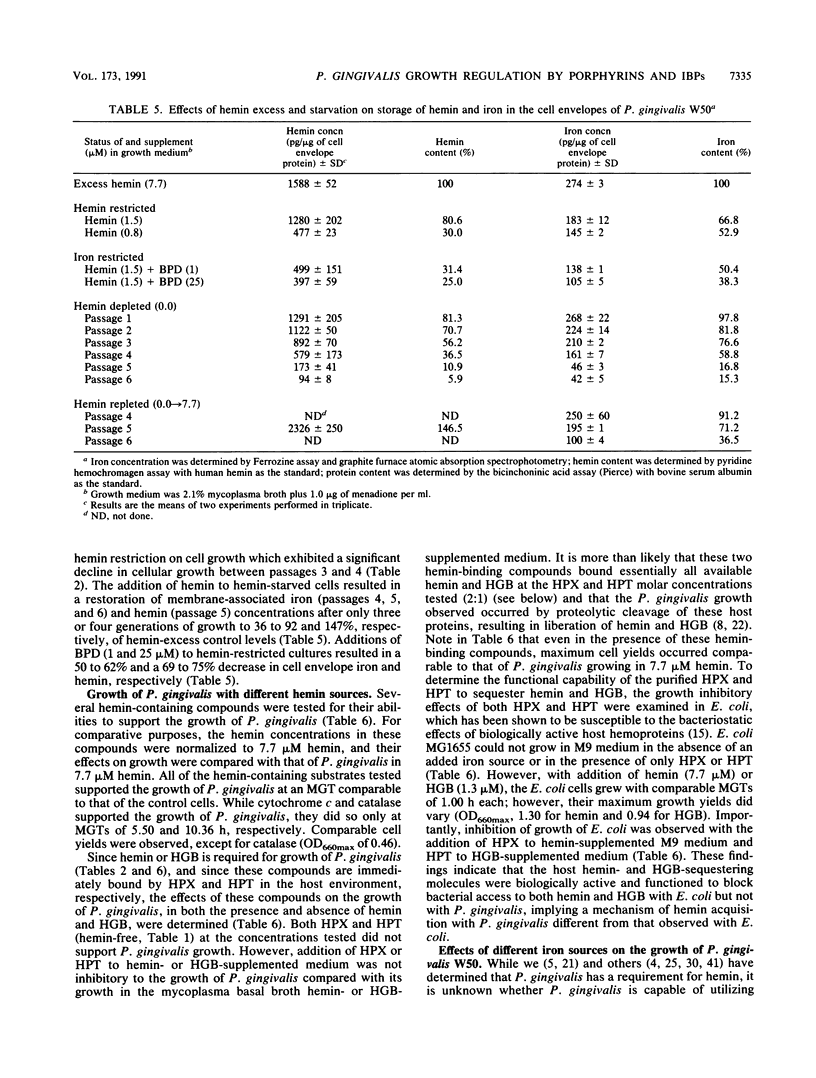

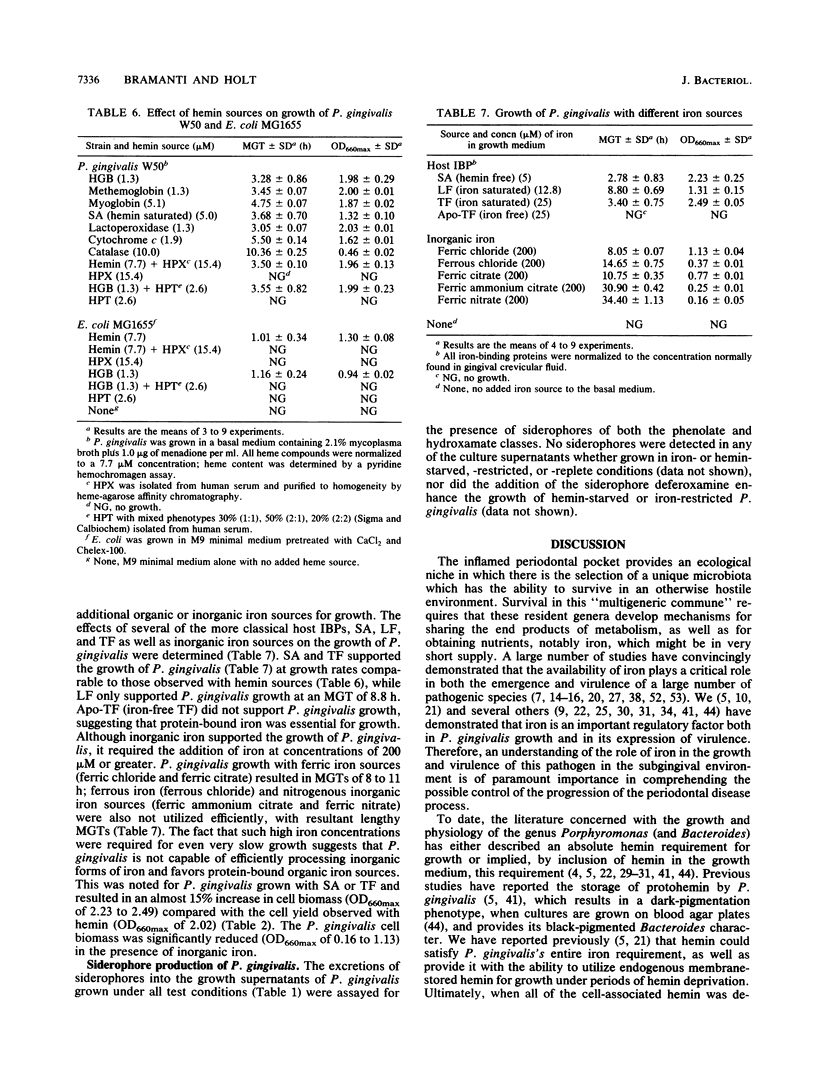

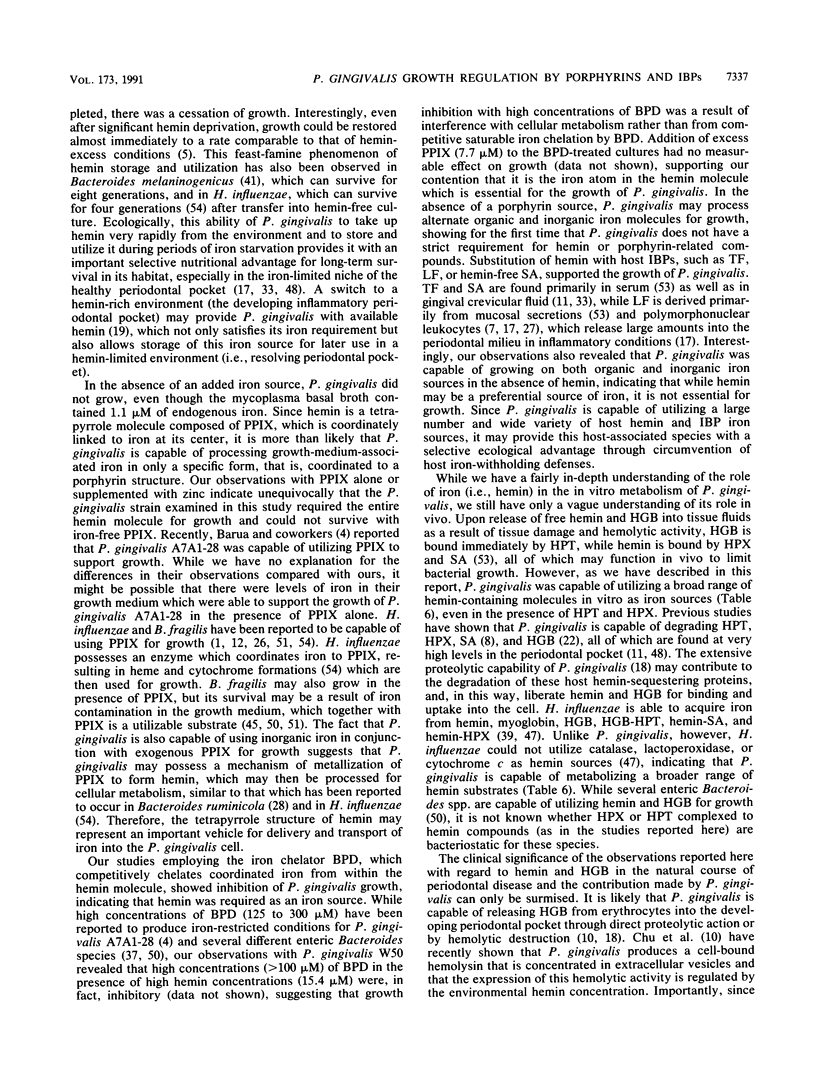

Porphyromonas gingivalis (Bacteroides gingivalis) requires iron in the form of hemin for growth and virulence in vitro, but the contributions of the porphyrin ring structure, porphyrin-associated iron, host hemin-sequestering molecules, and host iron-withholding proteins to its survival are unknown. Therefore, the effects of various porphyrins, host iron transport proteins, and inorganic iron sources on the growth of P. gingivalis W50 were examined to delineate the various types of iron molecules used for cellular metabolism. Cell envelope-associated hemin and iron stores contributed to the growth of P. gingivalis in hemin-free culture, and depletion of these endogenous reserves required eight serial transfers into hemin-free medium for total suppression of growth. Comparable growth of P. gingivalis was observed with 7.7 microM equivalents of hemin as hemoglobin (HGB), methemoglobin, myoglobin, hemin-saturated serum albumin, lactoperoxidase, cytochrome c, and catalase. Unrestricted growth was recorded in the presence of haptoglobin-HGB and hemopexin-hemin complexes, indicating that these host defense proteins do not sequester HGB and hemin from P. gingivalis. The iron chelator 2,2'-bipyridyl functionally chelated hemin-associated iron, resulting in dose-dependent inhibition of growth in hemin-restricted cultures at 1 to 25 microM 2,2'-bipyridyl concentrations. In the absence of an exogenous iron source, protoporphyrin IX did not support P. gingivalis growth. These findings suggest that the iron atom in the hemin molecule is the critical constituent for growth and that the tetrapyrrole porphyrin ring structure may represent an important vehicle for delivery of iron into the P. gingivalis cell. P. gingivalis does not have a strict requirement for porphyrins, since growth occurred with nonhemin iron sources, including high concentrations (200 muM) of ferric, ferrous, and nitrogenous inorganic iron, and P. gingivalis exhibited unrestricted growth in the presence of host transferrin, lactoferrin, and serum albumin. The diversity of iron substrates utilized by P. gingivalis and the observation that growth was not affected by the bacteriostatic effects of host iron-withholding proteins, which it may encounter in the periodontal pocket, may explain why P. gingivalis is such a formidable pathogen in the periodontal disease process.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Atkin C. L., Neilands J. B., Phaff H. J. Rhodotorulic acid from species of Leucosporidium, Rhodosporidium, Rhodotorula, Sporidiobolus, and Sporobolomyces, and a new alanine-containing ferrichrome from Cryptococcus melibiosum. J Bacteriol. 1970 Sep;103(3):722–733. doi: 10.1128/jb.103.3.722-733.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua P. K., Dyer D. W., Neiders M. E. Effect of iron limitation on Bacteroides gingivalis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990 Oct;5(5):263–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramanti T. E., Holt S. C. Iron-regulated outer membrane proteins in the periodontopathic bacterium, Bacteroides gingivalis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990 Feb 14;166(3):1146–1154. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90986-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramanti T. E., Wong G. G., Weintraub S. T., Holt S. C. Chemical characterization and biologic properties of lipopolysaccharide from Bacteroides gingivalis strains W50, W83, and ATCC 33277. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1989 Dec;4(4):183–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1989.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullen J. J. The significance of iron in infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1981 Nov-Dec;3(6):1127–1138. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.6.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson J., Höfling J. F., Sundqvist G. K. Degradation of albumin, haemopexin, haptoglobin and transferrin, by black-pigmented Bacteroides species. J Med Microbiol. 1984 Aug;18(1):39–46. doi: 10.1099/00222615-18-1-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman R. J., Ramakrishnan M. D., Harper F. H. Hemin levels in culture medium of Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis regulate both hemin binding and trypsinlike protease production. Infect Immun. 1990 Dec;58(12):4016–4019. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.4016-4019.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu L., Bramanti T. E., Ebersole J. L., Holt S. C. Hemolytic activity in the periodontopathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis: kinetics of enzyme release and localization. Infect Immun. 1991 Jun;59(6):1932–1940. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.1932-1940.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer D. W., West E. P., Sparling P. F. Effects of serum carrier proteins on the growth of pathogenic neisseriae with heme-bound iron. Infect Immun. 1987 Sep;55(9):2171–2175. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2171-2175.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton J. W., Brandt P., Mahoney J. R., Lee J. T., Jr Haptoglobin: a natural bacteriostat. Science. 1982 Feb 5;215(4533):691–693. doi: 10.1126/science.7036344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R. A., Sciortino C. V., McIntosh M. A. Role of iron in microbe-host interactions. Rev Infect Dis. 1983 Sep-Oct;5 (Suppl 4):S759–S777. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.supplement_4.s759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S. A., Mandel I. D., Herrera M. S. Lysozyme and lactoferrin quantitation in the crevicular fluid. J Periodontol. 1983 Jun;54(6):347–350. doi: 10.1902/jop.1983.54.6.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier D., Chao G., McBride B. C. Characterization of sodium dodecyl sulfate-stable Bacteroides gingivalis proteases by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Infect Immun. 1989 Jan;57(1):95–99. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.95-99.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanioka T., Shizukuishi S., Tsunemitsu A. Hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation of clinically healthy and inflamed gingiva in human subjects. J Periodontal Res. 1990 Mar;25(2):93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1990.tb00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms S. D., Oliver J. D., Travis J. C. Role of heme compounds and haptoglobin in Vibrio vulnificus pathogenicity. Infect Immun. 1984 Aug;45(2):345–349. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.2.345-349.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt S. C., Bramanti T. E. Factors in virulence expression and their role in periodontal disease pathogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1991;2(2):177–281. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay H. M., Birss A. J., Smalley J. W. Haemagglutinating and haemolytic activity of the extracellular vesicles of Bacteroides gingivalis W50. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990 Oct;5(5):269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennell W., Holt S. C. Comparative studies of the outer membranes of Bacteroides gingivalis, strains ATCC 33277, W50, W83, 381. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990 Jun;5(3):121–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskelo P., Muller-Eberhard U. Interaction of porphyrins with proteins. Semin Hematol. 1977 Apr;14(2):221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev M., Keudell K. C., Milford A. F. Succinate as a growth factor for Bacteroides melaninogenicus. J Bacteriol. 1971 Oct;108(1):175–178. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.1.175-178.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIver I., O'Reilly T., Brown M. R. Porphyrin ring source can alter the outer membrane protein profile of non-typable Haemophilus influenzae. J Med Microbiol. 1990 Mar;31(3):163–168. doi: 10.1099/00222615-31-3-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez J. L., Delgado-Iribarren A., Baquero F. Mechanisms of iron acquisition and bacterial virulence. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990 Mar;6(1):45–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall D. R., Caldwell D. R. Tetrapyrrole utilization by Bacteroids ruminocola. J Bacteriol. 1977 Sep;131(3):809–814. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.3.809-814.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermid A. S., McKee A. S., Marsh P. D. Effect of environmental pH on enzyme activity and growth of Bacteroides gingivalis W50. Infect Immun. 1988 May;56(5):1096–1100. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1096-1100.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee A. S., McDermid A. S., Baskerville A., Dowsett A. B., Ellwood D. C., Marsh P. D. Effect of hemin on the physiology and virulence of Bacteroides gingivalis W50. Infect Immun. 1986 May;52(2):349–355. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.349-355.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minhas T., Greenman J. Production of cell-bound and vesicle-associated trypsin-like protease, alkaline phosphatase and N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminidase by Bacteroides gingivalis strain W50. J Gen Microbiol. 1989 Mar;135(3):557–564. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-3-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan W. T. Porphyrin-binding proteins in serum. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1975 Apr 15;244:624–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb41558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S., Murphy R. A., Wawszkiewcz E. J. Effect of hemoglobin and of ferric ammonium citrate on the virulence of periodontopathic bacteria. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1988 Dec;3(4):192–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1988.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S. The role of crevicular fluid iron in periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1985 Nov;56(11 Suppl):22–27. doi: 10.1902/jop.1985.56.11s.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilands J. B. Microbial envelope proteins related to iron. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1982;36:285–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.36.100182.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto B. R., Sparrius M., Verweij-van Vught A. M., MacLaren D. M. Iron-regulated outer membrane protein of Bacteroides fragilis involved in heme uptake. Infect Immun. 1990 Dec;58(12):3954–3958. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.3954-3958.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto B. R., Verweij-van Vught A. M., van Doorn J., Maclaren D. M. Outer membrane proteins of Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides vulgatus in relation to iron uptake and virulence. Microb Pathog. 1988 Apr;4(4):279–287. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne S. M. Iron and virulence in the family Enterobacteriaceae. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1988;16(2):81–111. doi: 10.3109/10408418809104468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidcock K. A., Wooten J. A., Daley B. A., Stull T. L. Iron acquisition by Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1988 Apr;56(4):721–725. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.4.721-725.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizza V., Sinclair P. R., White D. C., Cuorant P. R. Electron transport system of the protoheme-requiring anaerobe Bacteroides melaninogenicus. J Bacteriol. 1968 Sep;96(3):665–671. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.3.665-671.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwyn B., Neilands J. B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem. 1987 Jan;160(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah H. N., Bonnett R., Mateen B., Williams R. A. The porphyrin pigmentation of subspecies of Bacteroides melaninogenicus. Biochem J. 1979 Apr 15;180(1):45–50. doi: 10.1042/bj1800045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry J. F., Appleman M. D., Wilkins T. D. Requirement of heme for growth of Bacteroides fragilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977 Oct;34(4):386–390. doi: 10.1128/aem.34.4.386-390.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull T. L. Protein sources of heme for Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1987 Jan;55(1):148–153. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.148-153.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefsen T., Saltvedt E. Comparative analysis of gingival fluid and plasma by crossed immunoelectrophoresis. J Periodontal Res. 1980 Jan;15(1):96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1980.tb00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui K., Mueller G. C. Affinity chromatography of heme-binding proteins: an improved method for the synthesis of hemin-agarose. Anal Biochem. 1982 Apr;121(2):244–250. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90475-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij-van Vught A. M., Namavar F., Vel W. A., Sparrius M., MacLaren D. M. Pathogenic synergy between Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis or B. vulgatus in experimental infections: a non-specific phenomenon. J Med Microbiol. 1986 Feb;21(1):43–47. doi: 10.1099/00222615-21-1-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE D. C., GRANICK S. HEMIN BIOSYNTHESIS IN HAEMOPHILUS. J Bacteriol. 1963 Apr;85:842–850. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.4.842-850.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg E. D. Iron and infection. Microbiol Rev. 1978 Mar;42(1):45–66. doi: 10.1128/mr.42.1.45-66.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg E. D. Iron withholding: a defense against infection and neoplasia. Physiol Rev. 1984 Jan;64(1):65–102. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1984.64.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]