Abstract

Background

Patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) may be managed with different treatment options. This study compared the effectiveness of three commonly used non‐surgical treatment modalities.

Methods

Subjects with mild to moderate OSA were randomised to one of three treatment groups for 10 weeks: conservative measures (sleep hygiene) only, continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) in addition to conservative measures or an oral appliance in addition to conservative measures. All overweight subjects were referred to a weight‐reduction class. OSA was assessed by polysomnography. Blood pressure was recorded in the morning and evening in the sleep laboratory. Daytime sleepiness was assessed with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Health‐related quality of life (HRQOL) was assessed with the 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐36) and Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI).

Results

101 subjects with a mean (SEM) apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI) of 21.4 (1.1) were randomised to one of the three groups. The severity of sleep‐disordered breathing was decreased in the CPAP and oral appliance groups compared with the conservative measures group, and the CPAP group was significantly better than the oral appliance group. Relief from sleepiness was significantly better in the CPAP group. CPAP was also better than the oral appliance or conservative measures in improving the “bodily pain” domain, and better than conservative measures in improving the “physical function” domain of SF‐36. Both CPAP and the oral appliance were more effective than conservative measures in improving the SAQLI, although no difference was detected between the CPAP and oral appliance groups. CPAP and the oral appliance significantly lowered the morning diastolic blood pressure compared with baseline values, but there was no difference in the changes in blood pressure between the groups. There was also a linear relationship between the changes in AHI and body weight.

Conclusion

CPAP produced the best improvement in terms of physiological, symptomatic and HRQOL measures, while the oral appliance was slightly less effective. Weight loss, if achieved, resulted in an improvement in sleep parameters, but weight control alone was not uniformly effective.

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a common disorder in various communities.1,2 Affected patients have neurocognitive and neurobehavioural impairment,3 and are at risk of developing long‐term vascular consequences.4 Continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) is widely considered as the treatment of choice because of its high and consistent efficacy on various outcome measures.5,6,7 Although it is controversial whether cardiovascular pathogenesis and clinical morbidity is proportional to the severity of OSA reflected by sleep indices, it has been suggested that those with severe sleep‐disordered breathing should be treated irrespective of symptoms, while those with milder disease are treated mainly for functional symptoms. Thus, for subjects with mild or moderate OSA, improvement in functional morbidity is the major goal of treatment. However, adherence to CPAP in these subjects is lower than in those with severe OSA,8 and this may compromise its overall effectiveness. The use of an oral appliance has been shown to reduce the severity of sleep‐disordered breathing and leads to symptomatic improvement, especially in mild to moderate OSA, and patients seem to be more compliant to this treatment than CPAP.9,10 Weight reduction has always been advocated in patients with OSA who are overweight, and may lead to improvement in the severity of OSA.11 In clinical practice, patients may express the desire to adopt weight‐control measures first before device use when they have only mild or moderate OSA. Unfortunately, weight loss is difficult to achieve and maintain.12

There have been several randomised studies on various treatment modalities in mild to moderate OSA. The studies comprised two treatment arms,9,10,13,14,15,16,17 except a recent trial from Australia in which three regimes were compared.18 Treatment outcome measures usually included sleep parameters and daytime sleepiness, while data on the comprehensive evaluation of functional status as reflected by health‐related quality of life (HRQOL) have been limited.14,16,17,18 This study was designed to assess the effectiveness of the three commonly used non‐surgical treatment modalities in mild to moderate OSA, with regard to daytime sleepiness, HRQOL and physiological parameters.

Methods

Subjects and study protocol

Subjects were consecutively recruited from the sleep laboratories of a university hospital and a regional hospital. Inclusion criteria were apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI) ⩾5–40 and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)19 >9 for those with AHI 5–20. Exclusion criteria were the presence of sleepiness which may constitute risk to self or others, unstable medical diseases, coexistence of sleep disorders other than OSA, history of previous surgery to upper airway (except those for nasal problems) and pregnant women. At baseline, all subjects underwent demographic documentation and anthropometric measurements. Blood pressure was recorded both on the night of polysomnography (PSG) and the next morning. Daytime sleepiness was assessed with ESS. HRQOL was assessed with the 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐36)20 and the Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI).21 Subjects were then randomised into three treatment groups: conservative measures only (advice on general sleep hygiene measures were given, and those who were overweight were asked to attend a weight‐control programme in the Dietetics Unit, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China; conservative measures group), conservative measures in addition to CPAP (CPAP group) or conservative measures in addition to an oral appliance (oral appliance group). According to Asian criteria for overweight and obesity, as explored by the World Health Organization, subjects were considered to be overweight if their body mass index was ⩾23 kg/m2.22,23 Those in the CPAP group were prescribed CPAP (ARIA LX, Respironics, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) at a pre‐titrated pressure. Subjects in the oral appliance group were referred to an orthodontist (KS) for a tailor‐made non‐adjustable oral appliance. The oral appliance was made of dental acrylic modified from a functional activator (Harvold type). It held the mandible in a forward direction with some vertical opening to keep the jaw at the most advanced position without causing discomfort.24

At 10 weeks, all subjects were reassessed with the same battery of tests as at the baseline. The CPAP and oral appliance groups underwent PSG using the respective device, and had another PSG without the assigned device after stopping its use for 1 week, in order to assess the effect of conservative measures on sleep parameters in these groups. The conservative measures group underwent PSG without any device.

The study was approved by the respective institutional ethics committee. All subjects gave written informed consent.

Polysomnography

Subjects underwent overnight PSG (Alice 3 or Alice 4 Diagnostics System, Respironics, Atlanta, USA) with documentation of sleep stages by EEG, respiratory movement by impedance plethysmography, air flow by nasal pressure sensor with thermistor back up, arterial oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, snoring by tracheal microphone and sleep position by position sensor. All sleep data and respiratory events were manually scored according to standard criteria.25,26

Blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured with Dinamap (Critikon, Tampa, Florida, USA) in the evening (20:00–21:00) on the day of admission to the sleep study and the next morning on waking (8:00–9:00). The average of three readings taken at 1 min intervals was documented as morning and evening blood pressure readings.

Health‐related quality of life assessment

Short‐Form Health Survey questionnaire (SF‐36)

This is a generic self‐completed questionnaire that measures eight dimensions of health: physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems (role‐physical), bodily pain, general health perceptions, energy/vitality, social functioning, role limitation due to emotional problems (role‐emotional) and mental health.20

Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI)

This is a sleep apnoea‐specific questionnaire consisting of four core domains: daily functioning, social interactions, emotional functioning and symptoms. The SAQLI also includes a domain specific for treatment‐related problems which is useful for comparing the effectiveness of different treatment options.21 The SAQLI was translated from English to Chinese following existing guidelines to preserve equivalence.27

Treatment adherence and treatment‐related side effects

Adherence to the assigned treatment was recorded at 4 weeks and at 10 weeks. Data regarding CPAP use were downloaded from the internal memory of the CPAP device and adherence to use of the oral appliance was assessed through self‐reporting. Body weight was measured. Side effects of treatment were evaluated by self‐reporting using questionnaires in a clinical setting.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was 105 subjects with 35 in each treatment group. The calculation was based on the analysis of variance with a minimum between‐group difference of three units in ESS, a standard deviation of four units,15 80% power, 5% chance of committing a type 1 error and 10% attrition. The randomisation list was generated by the Statistical Analysis System. Baseline comparisons among groups were made by analysis of variance. For the analysis by intention‐to‐treat (ITT), missing values were replaced by the baseline values. Within‐group comparison was examined by paired t test. Post‐treatment changes were analysed based on both the ITT principle with inclusion of all study patients and per‐protocol set which included only patients with observed outcomes. The comparisons were made by regression analysis with the adjustment of baseline values. A closed test procedure was used to account for multiplicity in post hoc comparisons. The association between changes in body weight and changes in AHI was examined by Pearson's correlation after checking for normality. To determine whether this association was independent of treatment exposure, linear regression was performed with change in AHI as the dependent variable. The independent variables included the change in body weight, treatment groups and the interaction between change in body weight and treatment group. Results are given as mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated. All statistical tests were two‐sided using 0.05 as the level of significance. All analyses were made in SPSS V.11.0.

Results

Subjects

In all, 109 subjects were approached and eight refused to join the study. Thus, 101 subjects were recruited with mean (SEM) AHI of 21.4 (1.1), and randomised into one of the three treatment arms (table 1). All subjects were advised on sleep hygiene measures with particular relevance to OSA and weight control. In addition, 84 subjects were referred to the weight‐control programme.

Table 1 Characteristics of study subjects.

| CM (n = 33) | CPAP (n = 34) | OA (n = 34) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 10 weeks | Baseline | 10 weeks | Baseline | 10 weeks | |

| Age (years) | 47 (2) | 45 (1) | 45 (2) | |||

| Male (%) | 26 (79) | 27 (79) | 26 (76) | |||

| Body weight (kg) | 74.8 (2.3) | 74.5 (2.2) | 75.8 (1.7) | 74.6 (1.6)* | 73.3 (1.9) | 72.3 (2.2) |

| Body mass index | 27.3 (0.6) | 27.1 (0.6) | 27.6 (0.6) | 27.2 (0.6)* | 27.3 (0.6) | 26.9 (0.6) |

| Morning sBP (mm Hg) | 125.5 (3.5) | 126.7 (3.7) | 127.9 (2.3) | 123.0 (2.5) | 127.1 (2.6) | 125.9 (3.3) |

| Morning dBP (mm Hg) | 74.2 (2.4) | 71.0 (1.9) | 77.0 (1.8) | 71.8 (2.2)* | 76.2 (2.1) | 73.4 (2.0)* |

| Evening sBP (mm Hg) | 127.2 (3.2) | 128.4 (3.9) | 130.9 (2.4) | 124.9 (3.4) | 131.9 (3.1) | 129.8 (3.7) |

| Evening dBP (mm Hg) | 73.5 (1.9) | 73.1 (1.8) | 78.0 (1.9) | 74.0 (2.1) | 77.8 (2.2) | 75.9 (2.0) |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale†,†† | 12 (1) | 10 (1)* | 12 (1) | 7 (1)** | 12 (1) | 9 (1)** |

| Apnoea–hypopnoea index‡,¶,†† | 19.3 (1.9) | 20.5 (2.5) | 23.8 (1.9) | 2.8 (1.1)** | 20.9 (1.7) | 10.6 (1.7)** |

| Minimum oxygen saturation (%) | 76.1 (2.6) | 77.4 (2.0) | 75.0 (1.4) | 87.2 (2.9)* | 73.8 (1.9) | 81.0 (1.6)* |

| Arousal index† | 23.5 (2.2) | 28.8 (2.5) | 21.6 (1.7) | 16.3 (1.8)* | 24.5 (2.2) | 21.6 (2.5) |

CM, conservative measures; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; dBP, diastolic blood pressure; OA, oral appliance; sBP, systolic blood pressure.

Within‐group comparison between baseline and 10 week reassessment: *p<0.05; **p<0.001.

Data are presented as mean (SEM), unless otherwise stated.

Between‐group comparison in the changes between baseline and 10 week reassessment: †p<0.05, ‡p<0.001 CM vs CPAP;

¶p<0.001 CM vs OA; ††p<0.05, CPAP vs OA.

Subjects randomised to the CPAP and oral appliance groups received the devices as described above; 10 subjects withdrew (one in the CPAP group due to intolerance of the device, four in the oral appliance group due to gum problems and five in the conservative measures group who refused to undergo PSG at 10 weeks). There was no significant difference in baseline demographics and sleep parameters between those who completed the study and those who did not.

Sleep study parameters

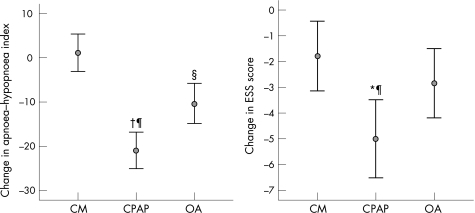

Compared with baseline, both CPAP and the oral appliance significantly improved hypoxaemia and AHI, although an AHI <5 could only be achieved by CPAP, and improvement in arousal index was only significant in the CPAP group (table 1). The conservative measures group showed no significant change in AHI. The difference in the improvement in AHI between the groups was statistically significant (fig 1). Compared with baseline, PSG performed on subjects in the CPAP and oral appliance groups (without using the assigned treatment) showed no significant change in sleep parameters (online supplementary fig R1; see http://thorax.bmj.com/supplemental).

Figure 1 Comparison of changes in apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) between groups between baseline and 10‐week reassessment. *p<0.05, CM vs CPAP, †p<0.001, CM vs CPAP; ‡p<0.05, CM vs OA, §p<0.001 CM vs OA; ¶p<0.001, CM vs OA. CM, conservative measures; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; OA, oral appliance.

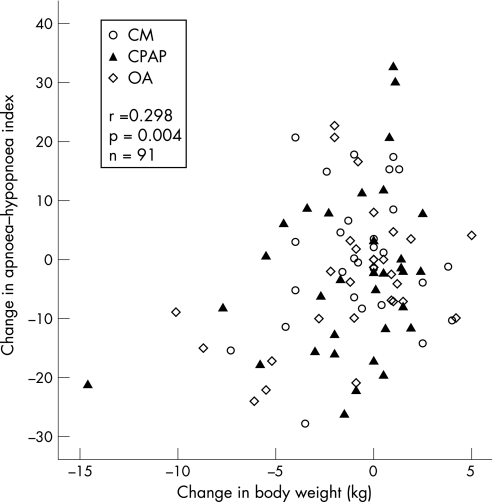

Of the 91 subjects who completed the study and underwent body weight measurement, 45 subjects had a decrease, 35 had an increase and 11 had no change in body weight. Among the 45 subjects (15, 15 and 15 subjects in conservative measures, oral appliance and CPAP groups, respectively) who had a decrease in body weight (from 75.8 (1.6) kg to 72.5 (1.5) kg), AHI decreased from 24.6 (1.7) to 19.1 (2.0). However, among the three groups, only subjects in the CPAP group had significant weight loss compared with their baseline values (table 1). Eight subjects achieved an AHI <5 (baseline AHI 14.6 (3.0)) on reassessment without a device, with an average weight loss of 2.9 (1.0) kg.

There was a linear relationship between the changes in AHI (without device use) and body weight (r = 0.298, p = 0.004; fig 2), which was independent of the treatment used.

Figure 2 Association between change in body weight (kg) and change in apnoea–hypopnoea index. For the CPAP and oral appliance groups, AHI values were taken from the 11 week PSG done without using a device.

Excessive daytime sleepiness

At 10 weeks, ESS scores significantly decreased in all three groups (table 1). The improvement in ESS score was greater with CPAP than with the oral appliance or conservative measures (fig 1).

Health‐related quality of life

36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey

At baseline, the scores of all domains of SF‐36 in subjects with OSA were lower than the norm scores (data not shown) of the local community.28 After treatment, CPAP led to improvement in six of the domains, except social functioning and mental health. Use of an oral appliance led to improvement in three domains: general health perceptions, vitality and role‐emotional. Conservative measures led to no significant change in any domains.

Comparison of the three groups showed that CPAP had significantly greater improvement than the oral appliance or conservative measures in the “bodily pain” domain, and than conservative measures in the “physical functioning” domain (table 2).

Table 2 Quality of life score of study subjects.

| CM (n = 33) | CPAP (n = 34) | OA (n = 34) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 10 weeks | Baseline | 10 weeks | Baseline | 10 weeks | |

| SAQLI | ||||||

| A: Daily functioning†§ | 5.4 (0.2) | 5.4 (0.2) | 5.4 (0.1) | 6.1 (0.2)** | 5.5 (0.2) | 5.9 (0.1)* |

| B: Social interactions | 5.8 (0.1) | 5.8 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.1) | 6.1 (0.1)** | 5.6 (0.2) | 5.9 (0.2) |

| C: Emotional ঠ| 5.5 (0.2) | 5.2 (0.2) | 5.3 (0.1) | 5.9 (0.1)** | 5.2 (0.2) | 5.8 (0.1)* |

| D: Symptoms ঠ| 3.7 (0.2) | 3.7 (0.2) | 3.7 (0.2) | 5.4 (0.2)** | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.9 (0.2)** |

| E: Treatment‐related symptoms†† | 2.6 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | ||||

| (A–D) SAQLI score‡¶†† | 5.1 (0.1) | 5.0 (0.1) | 5.0 (0.1) | 5.9 (0.1)** | 5.0 (0.2) | 5.6 (0.1)** |

| (A–E) SAQLI score†§ | 5.0 (0.1) | 5.5 (0.2)** | 5.5 (0.1)* | |||

| SF‐36 | ||||||

| Physical function† | 82.3 (2.6) | 78.9 (3.6) | 84.7 (2.2) | 88.2 (1.7)* | 84.7 (1.7) | 86.5 (2.0) |

| Role‐physical | 75.0 (5.9) | 68.0 (6.2) | 68.4 (6.9) | 82.4 (5.1)* | 66.9 (6.5) | 72.7 (6.0) |

| Bodily pain†,†† | 68.4 (4.2) | 69.2 (4.6) | 68.0 (4.0) | 80.5 (2.9)* | 72.2 (3.6) | 69.0 (4.2) |

| General health | 51.2 (3.3) | 54.8 (3.0) | 48.3 (3.1) | 58.9 (3.3)* | 50.8 (3.9) | 58.1 (3.7)* |

| Vitality | 52.7 (3.3) | 57.0 (2.8) | 52.6 (2.8) | 62.6 (2.9)* | 48.7 (2.9) | 56.7 (3.4)* |

| Social function | 82.6 (2.9) | 84.4 (3.2) | 79.4 (2.9) | 82.4 (3.5) | 80.5 (3.7) | 84.8 (3.5) |

| Role‐emotional | 67.7 (6.6) | 69.8 (6.3) | 56.9 (7.2) | 78.4 (5.6)* | 57.8 (7.1) | 74.7 (7.1)* |

| Mental health | 65.6 (2.5) | 68.0 (2.5) | 66.8 (2.5) | 71.8 (2.8) | 65.8 (2.9) | 69.8 (3.1) |

CM, conservative measures; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; OA, oral appliance; SAQLI, Calgary Sleep Apnoea Quality Of Life Index; SF‐36, MOS 36‐Item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire.

Data are presented as mean (SEM).

Within‐group comparison between baseline and 10 week reassessment: *p<0.05, **p<0.001.

Between‐group comparison in the changes between baseline and 10 week reassessment:

†p<0.05, ‡p<0.001 CM vs CPAP; §p<0.05, ¶p<0.001 CM vs OA; ††p<0.05 CPAP vs OA.

Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index

Compared with the baseline values, CPAP led to improvement in all four domains, the oral appliance led to improvement in three domains except social interaction, while the conservative measures group showed no significant change.

Among the three treatment groups, both CPAP and the oral appliance produced significantly greater improvement than conservative measures except for the “social interaction” domain (table 2). In terms of improvement in the total scores, CPAP was superior to the oral appliance if domain E was not included (ie, total score A–D), although the difference between the CPAP and the oral appliance groups no longer existed when domain E was included (ie, total score A–E; table 2).

There was essentially no difference in the results in the various outcome measures with ITT or per protocol analysis (data not shown).

Blood pressure

Of the 101 subjects, 19 were hypertensive and were receiving treatment (seven in the CPAP group, four in the oral appliance group and eight in the control group). There was no change in anti‐hypertensive medications during the study period in any subject. At 10 weeks, morning diastolic blood pressure significantly decreased in both the CPAP and the oral appliance groups when compared with their baseline, whereas systolic pressure in the morning and blood pressure in the evening showed no change (table 1). However, no significant difference was detected when comparing the changes in blood pressure between the groups.

Treatment adherence and complications

All subjects in the CPAP group reported some degree of side effects attributed to CPAP use, including dryness of the nose, mouth or throat (n = 16, 47%), feeling of pressure (n = 11, 32%), noise from machine (n = 8, 24%) and facial skin abrasion (n = 7, 21%). The mean (SEM) CPAP use was 4.4 (0.1) nights per week and 4.2 (0.1) h per night. In the oral appliance group, side effects experienced included excessive salivation (n = 19, 56%), temporomandibular joint discomfort (n = 13, 38%), dryness of the throat (n = 11, 33%) and tooth discomfort (n = 11, 33%). All side effects were considered as mild and acceptable. The self‐reported use of the treatment device was 5.2 (0.3) nights per week and 6.4 (0.2) h per night. No particular side effects related to lifestyle modification measures were reported.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of three commonly used treatment modalities for patients with mild to moderate OSA. Our findings showed that CPAP was superior to either an oral appliance or conservative measures in improving daytime sleepiness. Both CPAP and an oral appliance in addition to conservative management were more effective than conservative measures alone in improving sleep parameters and HRQOL. Both CPAP and oral appliance produced significantly greater improvements in sleep parameters than conservative measures, with CPAP superior to an oral appliance. Behavioural modification as a treatment measure alone may be of clinical benefit in some individuals, but as a group, it did not result in any significant change in sleep‐disordered breathing, daytime sleepiness or HRQOL.

Similar to previous reports, we showed that CPAP was superior to either an oral appliance or conservative management alone in improving sleep‐disordered breathing parameters. As the overall effectiveness of treatment intervention in chronic conditions depends heavily on adherence to treatment, the improvement in sleep parameters seen on a one‐night PSG while using a device may not adequately reflect its ultimate effectiveness alleviating the morbidity of OSA. Hence, functional assessment assumes a relatively major role in the evaluation of treatment effectiveness, especially in those with mild to moderate OSA in whom the concern for potential cardiovascular morbidity may be relatively less than in those with severe OSA.

CPAP has been shown to be effective in improving subjective sleepiness in subjects with severe OSA,29 but not consistently so in milder cases.13,14,16 We showed an improvement in subjective sleepiness compared with their baseline values in all three treatment arms, and those treated with CPAP had a greater improvement than either the oral appliance group or conservative measures group. Although we cannot rule out a placebo effect of the various interventions including weight reduction, the beneficial effect of CPAP beyond that of either conservative management alone or with an oral appliance was clearly shown. Despite a significant decrease in AHI in the oral appliance group, no significant difference in relieving daytime sleepiness was shown when compared with the conservative measures group. This could be due to limited sample size or the fact that the conservative measures group also showed some improvement in ESS.

It is well documented that HRQOL in severe OSA is impaired, and CPAP treatment can improve this.29 For subjects with milder disease, the effect of OSA treatment on HRQOL is more controversial, and the information has been mostly derived from studies with CPAP treatment,13,14 and a few recent studies comparing an oral appliance with CPAP.18,30,31 Both generic and sleep apnoea‐specific HRQOL questionnaires have been applied in this trial. The SF‐36 allows subjects to assess their ability in performing everyday activities and subsequent comparisons to be made between different groups of subjects with the same or different diseases, but it may not focus adequately on the area of interest in a particular disease or a specific intervention. The disease‐specific tool, SAQLI, measures different aspects of HRQOL that are important for OSA and compares the effectiveness of different treatment options. In a recent crossover study of CPAP, oral appliance and placebo pill, both CPAP and the oral appliance improved the quality of life (mean SF‐36 score), neuropsychological function and subjective sleepiness, and no differences were found between CPAP and the oral appliance. In our study, CPAP was significantly better than the oral appliance or conservative measures in improving certain domains of SF‐36. However, on using SAQLI, we found that the difference between CPAP and the oral appliance was no longer seen when domain E was included in the total score. Although it has been observed clinically in some patients that side effects associated with CPAP may have an impact on their subjective well‐being, it is probably the first time that it has been shown in a randomised study that the beneficial effects of CPAP on HRQOL may be reduced by treatment‐related side effects. This has significant clinical implications because adherence to any treatment is probably affected by both its efficacy and treatment‐related problems.

There is evidence of a causal role of OSA in hypertension, and several randomised controlled studies have shown that CPAP may decrease blood pressure in both normotensive and hypertensive subjects with severe OSA,5 while one study has also shown a similar beneficial effect of an oral appliance compared with a placebo device in subjects with mild or moderate OSA.32 We were able to show a difference in morning diastolic blood pressure within the CPAP and oral appliance groups, but there was no significant difference in the changes among groups. Our finding was at variance with that of the randomised crossover study which similarly comprised subjects with mild or moderate OSA, where a significant improvement in night diastolic blood pressure was only seen with oral appliance treatment, compared with CPAP or placebo pill.18 The lack of any intergroup difference in our study may be due to the lesser severity of OSA in the study subjects compared with previous randomised trials, a small insignificant effect of conservative measures alone and/or the difference in the method of blood pressure monitoring. Nonetheless, our finding of within‐group differences in both the CPAP and oral appliance groups, but not in the conservative measures group, suggests that a beneficial effect on blood pressure can be achieved if the sleep‐disordered breathing is effectively controlled.

Obesity is one of the major risk factors for OSA. A population‐based longitudinal study showed that a 10% weight gain predicted an increase in AHI of approximately 32%, while a 10% weight loss predicted a 26% decrease in AHI.11 Our results confirmed that weight change correlated with change in AHI. With weight reduction alone, only about 10% of the subjects achieved an AHI <5. This could be related to insufficient weight loss for most subjects. Furthermore, weight loss alone may not necessarily lead to complete resolution of sleep apnoea as craniofacial factors also have a role in the development of OSA, especially in Chinese subjects.33,34 Weight‐control measures are often requested as a first option of management by many patients who are overweight and who have OSA, and who do not like the idea of using a device every night. It is disappointing that, as a group, those on conservative measures alone had no significant decrease in body weight, improvement in sleep parameters or improvement in HRQOL. However, weight control should still be advised as sleep‐disordered breathing is improved in individuals who lose weight. Among the three groups, only the CPAP group showed a significant decrease in body weight. It is possible that these subjects were more motivated or energetic after CPAP treatment to adhere to weight‐control measures, although this hypothesis was not substantiated by a recent study.35

There are several limitations in our study. First, there was no control group without any form of intervention or with a placebo device. However, the differences in the effects between the CPAP group and the oral appliance group would suggest that the beneficial effect of CPAP over conservative measures alone could not be solely attributed to a placebo effect of device use. Second, we used a non‐adjustable oral appliance, and the results may not be generalisable to other oral appliance models. However, the magnitude of improvement in sleep parameters with the oral appliance was similar to that in most other reported series. It is possible that, if an oral appliance could correct sleep‐disordered breathing events to the same extent as CPAP, the improvement in functional and other outcome measures might also be similar to that seen with CPAP treatment.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Agnes Lai for assistance in statistical analysis and preparation of the manuscript, and Ms Audrey Ip and Pui Pui Ku for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

AHI - apnoea–hypopnoea index

CPAP - continuous positive airways pressure

ESS - Epworth Sleepiness Scale

HRQOL - health‐related quality of life

ITT - intention‐to‐treat

OSA - obstructive sleep apnoea

PSG - polysomnography

SAQLI - Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by a grant award from the Health Services Research Committee, Hong Kong

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Young T, Peppard P E, Gottlieb D J. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20021651217–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ip M S M, Lam B, Tang L C H.et al A community study of sleep disordered breathing in middle‐aged Chinese women in Hong Kong—prevalence and gender differences. Chest 2004125127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett L S, Barbour C, Langford B.et al Health status in obstructive sleep apnea: relationship with sleep fragmentation and daytime sleepiness, and effects of continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19991591884–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quan S F, Gersh B J. Cardiovascular consequences of sleep‐disordered breathing: past, present and future: report of a workshop from the National Center on Sleep Disorders Research and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation 2004109951–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giles T L, Lasserson T J, Smith B J.et al Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006(1)CD001106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Engleman H M, Martin S E, Deary I J.et al Effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on daytime function in sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Lancet 1994343572–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepperell J C, Ramdassingh‐Dow S, Crosthwaite N.et al Ambulatory blood pressure after therapeutic and subtherapeutic nasal continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomised parallel trial. Lancet 2002359204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McArdle N, Devereux G, Heidarnejad H.et al Long term use of CPAP therapy for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19991591108–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson K A, Ono T, Lowe A A.et al A randomized crossover study of an oral appliance vs nasal‐continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of mild‐moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 19961091269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randerath W J, Heise M, Hinz R.et al An individually adjustable oral appliance vs continuous positive airway pressure in mild‐to‐moderate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 2002122569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peppard P E, Young T, Palta M.et al Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep‐disordered breathing. JAMA 20002843015–3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sampol G, Munoz x, Sagales M T.et al Long‐term efficacy of dietary weight loss in sleep apnoea/hypopnea syndrome. Eur Respir J 1998121156–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redline S, Adams N, Strauss M E.et al Improvement of mild sleep‐disordered breathing with CPAP compared with conservative therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998157858–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes M, Houston D, Worsnop C J.et al A randomized controlled trial of continuous positive airway pressure in mild obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002165773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monasterio C, Vidal S, Duran J.et al Effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure in mild sleep apnea‐hypopnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001164939–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotsopoulos H, Chen C, Qian J.et al Oral appliance therapy improves symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea: a randomised controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002166743–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engleman H M, Martin S E, Deary I J.et al Effect of CPAP therapy on daytime function in patients with mild sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax 199752114–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes M, McEvoy D, Banks S.et al Efficacy of positive airway pressure and oral appliance in mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004170656–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johns M W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 199114540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McHorney C A, Ware J E, Jr, Raczek A E. The MOS 36‐Item Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 199331247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flemons W W, Reimer M A. Development of a disease‐specific health‐related quality of life questionnaire for sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998158494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Diabetes Institute, World Health Organization The Asia‐Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Melbourne, Australia: Health Communications Australia, 200015–21.

- 23.WHO expert consultation Appropriate body‐mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004363157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sam K, Lam B, Ooi C G.et al Effect of a non‐adjustable oral appliance on upper airway morphology in obstructive sleep apnoea. Respir Med 2006100897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A A. eds. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. NIH publication no. 204. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1968

- 26.American Sleep Disorders Association EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples (ASDA Report). Sleep 199215173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mok W Y, Lam C L, Lam B.et al A Chinese version of the Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index was evaluated for reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Clin Epidemiol 200457470–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam C L, Gandek B, Ren X S.et al Tests of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF‐36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 199851139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montserrat J M, Ferrer M, Hernandez L.et al Effectiveness of CPAP treatment in daytime function in sleep apnea syndrome: a randomized controlled study with an optimised placebo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001164608–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engleman H M, McDonald J P, Graham D.et al Randomized crossover trial of two treatments for sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: continuous positive airway pressure and mandibular repositioning splint. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002166855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan Y K, L'Estrange P R, Luo Y M.et al Mandibular advancement splints and continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomized cross‐over trial. Eur J Orthod 200224239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gotsopoulos H, Kelly J J, Cistulli P A. Oral appliance therapy reduced blood pressure in obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Sleep 200427934–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lam B, Ooi C G C, Peh W C G.et al Computed tomographic evaluation of the role of craniofacial and upper airway morphology in obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) subjects in Chinese. Respir Med 200498301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lam B, Ip M S, Tench E.et al Craniofacial profile in Asian and white subjects with obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 200560504–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kajaste S, Brander P E, Telakivi T.et al A cognitive‐behavioral weight reduction program in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome with or without initial nasal CPAP: a randomized study. Sleep Med 20045125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]