Abstract

With the improving survival of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF), the clinical spectrum of this complex multisystem disease continues to evolve. One of the most important clinical events for patients with CF in the course of this disease is an acute pulmonary exacerbation. Clinical and microbial epidemiology studies of CF pulmonary exacerbations continue to provide important insight into the course, prognosis and complications of the disease. This review provides a summary of the pathophysiology, clinical epidemiology and microbial epidemiology of a CF pulmonary exacerbation.

With the improving survival of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF), the clinical spectrum of this complex multisystem disease continues to evolve. One of the most important clinical events for patients with CF in the course of this disease is an acute pulmonary exacerbation. The primary goal of this review is to provide a summary of the pathophysiology, clinical epidemiology and microbial epidemiology of a CF pulmonary exacerbation. Previous reviews of this subject have been done, but without the focus on both clinical and microbial epidemiology.1

Pathophysiology of CF pulmonary exacerbation

Much of the morbidity and mortality associated with CF is related to the pulmonary system, primarily the upper and lower airways. Extensive basic research has advanced our understanding of the primary defect in CF (mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR)) and the potential pathophysiological implications of this defect. Although no definitive work has fully explained how mutations in CFTR lead to airways disease in CF, the most prominent hypothesis to explain this phenomenon is the “low volume hypothesis”.2,3 Based on in vitro data, the proposed mechanism of CF airways disease is that, because of sodium hyperabsorption and lack of chloride absorption, the volume of the periciliary lining fluid decreases with relative dehydration of the layer. This leads to low volume of fluid, impaired cilary function and slower mucociliary transport allowing bacterial overgrowth. With infection, neutrophils are recruited to the airway with subsequent release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines leading to a vicious cycle of chronic infection and inflammation that ultimately injures the airways. The supportive evidence for this in vitro hypothesis comes from a mouse model of CF lung disease in which epithelial sodium channels are overexpressed4 and clinical trials in patients with CF.5,6 A more recent additional model that may be compatible with this “low volume hypothesis” relates to the evidence suggesting a lack of mucus secretion, potentially due to defective anion‐mediated fluid absorption within the CF airway glands.7,8,9

Despite our detailed understanding of CF at a cellular level, very little is known about the pathophysiology of recurrent episodes of increasing pulmonary symptoms termed exacerbations. Exacerbations of pulmonary disease are very common and present clinically with changes in cough, sputum production, dyspnoea, decreased energy level and appetite, weight loss and decreases in spirometric parameters. These episodes are probably related to a complex relationship between host defence and airway microbiology that impacts on sputum production and airflow obstruction. Viral infections, including respiratory syncytial virus, may play a role in the initiation of these events,10 although data regarding the impact of vaccination against viral infection are limited.11,12 Pulmonary exacerbations have also been associated with the acquisition of new organisms or with a change in the bacterial density of colonising flora.13,14,15,16 Bacterial concentrations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are high during an exacerbation and decrease with treatment; and treatment with antimicrobial agents reduces symptoms and improves lung function.13,14,17 Interestingly, recent data suggest that the majority of exacerbations are not due to acquisition of new strains of Pseudomonas but a clonal expansion of existing strains.18 An inflammatory response in the airway in conjunction with the increase in bacterial concentration and polymorphonucleocytes has been documented with increases in interleukin (IL)8, IL6, IL1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)α, leukotriene B4 and free neutrophil elastase; these inflammatory mediators have been noted to decrease with treatment of the pulmonary exacerbation.19,20,21,22,23,24 Recent controlled clinical trials have shown that mucolytics, inhaled aminoglycosides, oral macrolides and inhaled hypertonic saline all reduce the rate of pulmonary exacerbations in CF.17,25,26,27

Clinical epidemiology of CF pulmonary exacerbation

Definitions/diagnosis

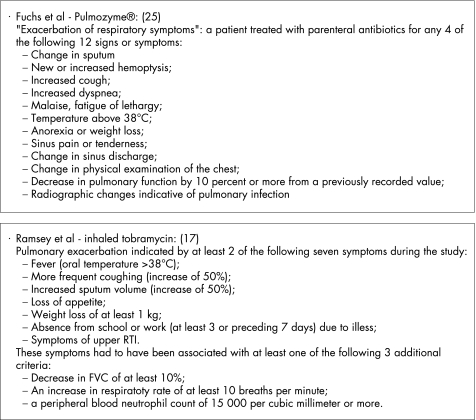

Despite calls for a consensus diagnosis of pulmonary exacerbations by a CF Outcomes Group in 1994 and in a more recent editorial,28,29 no consensus diagnostic criteria exist. Clinical diagnostic criteria commonly used can be found in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation clinical practice guidelines.30 Definitions have been used in major clinical trials evaluating new treatments in CF. These definitions have been based on empirical data, but have not been formally validated (fig 1).17,25,27 They have combined patient symptomotology, laboratory data and clinician evaluation.17,25 These definitions of a pulmonary exacerbation have revolved around the clinician's decision to treat a constellation of symptoms, but a treatment decision‐defined outcome is, by its nature, problematic. Within the US, practice patterns are far from uniform with regard to the treatment decision for a pulmonary exacerbation,31 so using a treatment decision in the definition is a problem.

Figure 1 Diagnostic criteria of a pulmonary exacerbation used by Fuchs et al25 and Ramsey et al.17

Two additional scoring systems were developed to diagnose pulmonary exacerbations and were used in two recent phase 2 CF clinical trials. The first score used was the Acute Respiratory Illness Checklist (ARIC).11,12 It was used as a symptom score to identify patients with lower respiratory tract infections, with the goal of capturing a wider spectrum of CF exacerbations in study participants. The second diagnostic score was the Respiratory and Systemic Symptoms Questionnaire (RSSQ; M W Konstan, personal communication); this score was created to have a uniform approach to identifying CF‐related pulmonary exacerbations including mild events not necessitating intravenous antibiotics. Table 1 compares the signs and symptoms assessed in these four different instruments to diagnose a CF pulmonary exacerbation. Despite this work, no consensus has been reached regarding the diagnostic criteria for a pulmonary exacerbation.

Table 1 Symptom profiles used in various definitions of a pulmonary exacerbation.

| Fuchs | Ramsey | ARIC | RSSQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms (new or increased) | ||||

| Pulmonary signs and symptoms | ||||

| Increased dypsnoea with exertion | × | × | ||

| Decreased exercise tolerance | × | |||

| Increased work of breath | × | |||

| Cough | × | × | × | |

| Day cough | × | |||

| Night cough | × | |||

| Wet or congested cough | × | |||

| Chest congestion | × | × | ||

| Frequency of cough | × | |||

| Cough up mucus | × | |||

| Wheezing | × | |||

| Haemoptysis/coughing up blood | × | × | × | |

| Sputum volume | × | × | × | × |

| Change in sputum appearance | × | × | ||

| Change in sputum colour | × | × | ||

| Change in sputum consistency | × | × | ||

| Increased respiratory rate | × | |||

| Decreased lung function | × | × | ||

| Upper respiratory tract symptoms | ||||

| Sore throat/runny nose | × | × | ||

| Sinus pain/tenderness | × | × | ||

| Change in sinus discharge | × | × | ||

| Constitutional and GI signs and symptoms | ||||

| Malaise/fatigue/lethargy | × | × | ||

| Abdominal pain | ||||

| Fever | × | × | × | |

| Decreased appetite/anorexia | × | × | × | |

| Weight loss | × | × | ||

| Work/school absenteeism | × | × |

ARIC, Acute Respiratory Illness Checklist; RSSQ, Respiratory and Systemic Symptoms Questionnaire (© Boehringer Ingelheim).

Components of these definitions have been examined to see which clinical characteristics best predict a pulmonary exacerbation.32,33,34 Rosenfeld and colleagues, using data from a clinical trial, used a multivariate modelling approach to create an algorithm to identify participants with a pulmonary exacerbation.33 Symptoms rather than physical examination and laboratory values were found to be more predictive of a pulmonary exacerbation. Two additional studies have noted very similar results.32,34 The signs and symptoms that were most predictive of a pulmonary exacerbation in all of these studies were increased cough, change in sputum (volume or consistency), decreased appetite or decreased weight, change in respiratory examination and respiratory rate.1 This work points to the clear need to focus on signs and symptoms in any future consensus diagnostic criteria.

Mild versus severe exacerbations

Mild CF pulmonary exacerbations have received very little attention and no clear definition exists in the literature. There is a spectrum of clinical presentations of exacerbations from clinical events managed as an outpatient to those requiring admission to an intensive care unit (ICU). One could hypothesise that the mild CF pulmonary exacerbation might present as an early precursor of a severe exacerbation, a milder version of a severe exacerbation or an isolated clinical event that does not evolve into a clear lower respiratory tract infection. Detailed natural history data may elucidate which of these patterns predominates and clarify whether particular clinical characteristics predict the outcome of mild events. Evidence in the literature regarding chronic obstructive lung disease suggests that early aggressive treatment of pulmonary exacerbations in that disease improve the longer term clinical outcome;35 this could also be the case in CF. Recent observational data suggest that patients in US CF care centres in the highest quartile of lung function had more courses of intravenous antibiotics than those in the lowest quartile of lung function, suggesting a link between aggressive care and outcome.31 To explore fully this treatment approach in CF, it is necessary to be able to identify mild or early CF pulmonary exacerbations.

More recent data have been published regarding severe pulmonary exacerbations using variable definitions. Ellaffi and colleagues36 have recently presented data on 1 year outcomes for severe CF exacerbations in 69 patients, 29 of whom were admitted to the ICU. Overall 1 year survival in subjects admitted to the ICU was 52%. This figure concurs with other work in which the 1 year survival of CF patients admitted to ICUs at six university hospitals in Paris was 57%; only 14% (6/42 adults) of the cohort died during their first ICU admission.37 Multivariate predictors of mortality included annual decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), simplified acute physiology score II (SAPS II) and the use of invasive mechanical ventilation. Improved outcomes have also recently been noted using non‐invasive oxygen and bi‐level ventilation.38 Given advances in non‐invasive ventilation, these mortality rates are better overall than those reported in the 1990s when ICU mortalities (rather than 1 year mortality) ranged from 32% to 55%.39,40 Evidence regarding invasive mechanical ventilation for patients with severe pulmonary exacerbations is limited but generally points to a poor outcome, particularly in adults.41

Pulmonary exacerbation rates

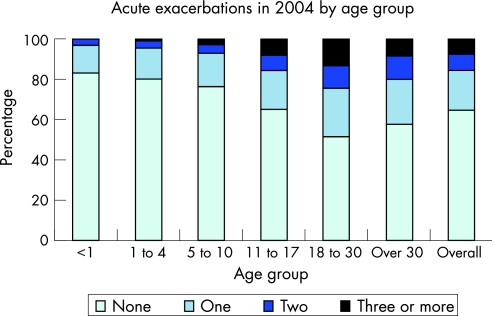

CF pulmonary exacerbation rates increase with age and more severe pulmonary impairment. Annual rates of CF pulmonary exacerbations by age and by FEV1 in the US CF Patient Registry are shown in figs 2, 3A and 3B. The pulmonary exacerbation rate was defined as a CF‐related pulmonary condition requiring admission to hospital or use of home intravenous antibiotics. The percentage of patients with CF experiencing one or more pulmonary exacerbations per year rises when subjects become teenagers and young adults (fig 2). Additional data from the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis noted an increasing annual rate at which patients with CF required intravenous antibiotics for pulmonary exacerbations with increasing age (increasing from 23% in subjects under age 6 years to 63% in those over the age of 18).34 Data from the US CF Patient Registry (fig 3A and B) delineate the relationship between lung function and pulmonary exacerbation rate. For adults the relationship is linear, with increasing exacerbation rates with decreasing lung function, while in children the relationship is non‐linear (more consistent with an exponential fall in the exacerbation rate with higher FEV1). In both cases, better lung function, as measured by FEV1 percentage predicted, is associated with fewer pulmonary exacerbations.

Figure 2 Graph showing the proportion of patients with CF by age group in the US CF Registry population who experienced no exacerbations, one exacerbation, two exacerbations or three or more exacerbations during the year 2004. Data from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry, 2004 Annual Data Report to the Center Directors.83 © Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2005.

Figure 3 Mean annual rate of pulmonary exacerbation per decile of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) percentage of predicted (each decile represents 10% of the total population) in (A) patients with CF <18 years of age and (B) patients ⩾18 years of age. The data represent the mean FEV1 percentage of predicted for 2004 in the US CF Registry in each decile of the population.

CF pulmonary exacerbation as a predictor and outcome variable

The annual rate of CF pulmonary exacerbations has clearly been associated with 2 year and 5 year survival in two separate prediction models evaluating the odds of death during follow‐up.42,43,44,45 CF pulmonary exacerbations requiring intravenous antibiotics have also been associated with later diminished lung function in children aged 1 to 6 years,46 with CF‐related diabetes,47 with sleep disturbances and with health‐related quality of life.48,49 It is an important marker of disease severity and, as such, has been used as an adjustment variable in studies of survival50,51,52 and an important outcome measure when assessing the impact of socioeconomic status and environmental exposure on CF.53,54 The pulmonary exacerbation rate has also been used as an important variable to assess new outcome measures such as high resolution computed tomography of the chest or cough frequency.55,56 It will also be essential for assessing future outcome measures. The pulmonary exacerbation rate is clearly in the causal pathway of pulmonary decline in CF, thus linking an outcome to this rate strengthens its validity.

Microbiological epidemiology of a CF pulmonary exacerbation

Microbiological diagnosis

Chronic bacterial airway infections are characteristically seen in the majority of individuals with CF. These infections are commonly polymicrobial and rarely can be eradicated with antimicrobial treatment. “Polymicrobial” is defined as an individual patient at a particular point of time infected with a number of different organisms. Knowledge of the natural history of colonisation (culture positivity in the airway) and infection (culture positivity with an associated specific host serological response) can be helpful in the management of CF pulmonary exacerbations. However, the epidemiology can only be established with adequate diagnostic microbiology testing.

Culture of respiratory tract specimens from individuals with CF can present challenges to microbiology laboratories unaccustomed to processing them because of problems related to sample viscosity, the polymicrobial nature of infections and slow bacterial growth. In addition, many of the available commercial systems for organism identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing are inaccurate for CF pathogens.57,58,59,60 CF secretions are frequently very viscous, requiring special processing to sample the entire specimen adequately.61 This is probably due to a combination of the primary defect in CFTR, which results in dehydrated airway mucus, and the purulence resulting from airway inflammation. For this reason, CF samples may be treated with dithiothreitol, DNase, or another solubilising agent to decrease viscosity.

Polymicrobial infections are the norm in CF airway infections and can be problematic since the organisms in the specimen may have very different growth requirements. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is often present and, because of its mucoid phenotype, frequently overgrows both Gram‐positive bacteria such as Staphylococcusaureus and more fastidious or slower growing Gram‐negative organisms such as Haemophilus influenzae and Burkholderia cepacia complex. The use of selective media, which inhibit the growth of P aeruginosa, is very useful for the isolation of S aureus and H influenzae and is mandatory for the isolation of B cepacia complex (table 2).61,62,63,64 In addition, multiple subcultures may need to be performed to isolate pure bacterial cultures for identification and susceptibility testing. Slow bacterial growth also requires that culture plates receive prolonged incubation. Laboratories specialising in CF microbiology frequently use incubation times of 48 h for cultures expected to yield P aeruginosa, and up to 96 h before reporting a culture negative for B cepacia complex.63

Table 2 Recommended culture conditions for CF pathogens from respiratory samples.

| Bacteria | Recommended media condition* | Special conditions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus | Mannitol salt agar | |||

| Columbia/colistin‐nalidixic acid agar | ||||

| Haemophilus influenzae | Horse blood or chocolate agar (may be supplemented with 300 μg/ml bacitracin) | Incubate anaerobically | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MacConkey agar | |||

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | BCSA OFPBL agar PC agar | Enhanced detection of slow‐growing colonies by incubation up to 4 days | ||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | MacConkey agar VIA agar | DNase agar used for confirmation | ||

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans | MacConkey agar | |||

*Media listed are commercially available.

Once isolated, organism identification may also be difficult, both because of the presence of a large number of unique bacteria and because of the phenotypic changes that even the more common organisms may undergo. The use of standard biochemical testing rather than commercial systems has been recommended for identification of Gram‐negative non‐fermenting bacteria.57,58 In addition, molecular techniques, especially polymerase chain reaction, have proved useful for bacterial identification, both directly in sputum and for isolated organisms growing in pure culture.65,66,67,68

Microbiological sampling

Sampling of lower airway secretions is considered essential for determining the infectious aetiology of pulmonary exacerbations in CF. This is most readily accomplished using expectorated sputum. However, some individuals with CF are unable to expectorate. This is most common in young children. Bronchoalveolar lavage is an excellent way of sampling the lower airway in non‐expectorating CF individuals, but this is too invasive for routine culturing.

Oropharyngeal swabs have served as a surrogate but may not be representative of lower airway infection.69,70 Rosenfeld and colleagues compared oropharyngeal swab cultures with simultaneous bronchoalveolar lavage cultures in 141 young children.70 For predicting growth of P aeruginosa from the lower airway in subjects aged 18 months or younger, oropharyngeal cultures had a sensitivity of 44% and a specificity of 95%. H influenzae was similar, but the specificity was significantly lower for S aureus. Oropharyngeal swabs obtained after chest physiotherapy were found to have increased sensitivity and specificity for the detection of both P aeruginosa and S aureus compared with swabs obtained before physiotherapy.71

Hypertonic saline induction of sputum has been reported to be a good surrogate for lower airway sampling in CF.72,73 Several studies suggest that induced sputum may be more sensitive in detecting bacteria in the lower airway than expectorated sputum and even bronchoalveolar lavage.73,74,75 Sputum induction has been used to monitor both inflammation and infection after intravenous antibiotic treatment for pulmonary exacerbations in CF.23

Organisms

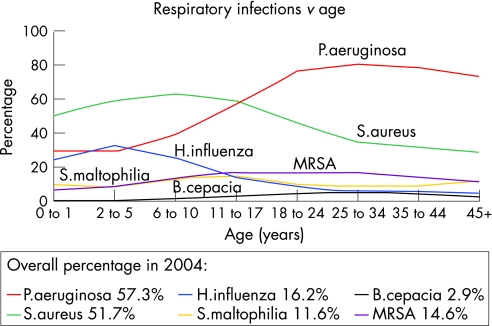

Chronic CF airway infections are commonly caused by one or more of a characteristic set of bacterial pathogens that appear to be acquired in an age‐dependent sequence (fig 4). Of the most frequently identified bacterial organisms causing airway infections in CF, only S aureus is generally considered to be pathogenic in individuals who are not immunocompromised. P aeruginosa, B cepacia complex, non‐typeable H influenzae, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Achromobacter xylosoxidans are often considered opportunistic pathogens. All of these organisms can variably be associated with pulmonary exacerbations in CF. Other chronically infecting organisms seen in CF that are also generally non‐pathogenic in the healthy host include Aspergillus and non‐tuberculous mycobacteria. These organisms are usually not associated with exacerbations in patients with CF.

Figure 4 Prevalence of selected respiratory pathogens in respiratory cultures of CF patients by age. Data from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry, 2004 Annual Data Report to the Center Directors.83 © Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2005.

Early infections in CF airways are most frequently caused by S aureus and H influenzae, organisms that may be seen in other young children with chronic illnesses and in adults with non‐CF bronchiectasis. S aureus is often the first organism cultured from young children with CF.76 However, there continues to be debate about the significance of S aureus in the pathogenesis of CF lung infection.77 Historically, significant improvements in patient longevity have been associated with the advent of anti‐staphylococcal therapy.78 However, several published studies of the efficacy of prophylactic anti‐staphylococcal antibiotics have not demonstrated clinical improvement in the treated populations.79,80

Non‐typeable H influenzae is also isolated from the respiratory tract early in the course of CF. In natural history studies of prospectively followed infants with CF, including those identified by neonatal screening, H influenzae was the most common organism isolated from lower airway cultures in the first year of life.69,81 Although H influenzae is associated with exacerbations in patients with non‐CF bronchiectasis,82 its role in progressive airway infection and inflammation in patients with CF is unclear.

P aeruginosa is by far the most significant pathogen in CF. Up to 80% of patients with CF are eventually infected with P aeruginosa,83 and acquisition of Pseudomonas, particularly organisms producing mucoid exopolysaccharide, is associated with clinical deterioration.46,84,85,86,87P aeruginosa isolates from the lungs of patients with CF are phenotypically quite distinctive. These characteristics—including mucoidy, lipopolysaccharide changes (loss of O‐side chains, distinctive acylation), loss of flagella‐dependent motility, increased auxotrophy, and antibiotic resistance—are not present in isolates causing initial colonisation.88,89,90,91,92 Early isolates look much like environmental isolates in their phenotype. Phenotypic changes appear to be selected within the CF airways and are more frequent when patients have been infected for a prolonged period of time. The ability to form biofilms may also be increased in chronic P aeruginosa isolates from individuals with CF.93

Several studies have demonstrated multiple genotypes of P aeruginosa present in a single sputum sample. Thus, Aaron and colleagues (as noted above) investigated how commonly acquisition of a new genotype of P aeruginosa was associated with a CF exacerbation.18 Among 80 individuals followed for 2 years with quarterly sputum cultures, 40 patients experienced a pulmonary exacerbation. Only 36 had isolates that could be genotyped and, of those, only two subjects demonstrated acquisition during exacerbation of a new clone that had not been present during a period of clinical stability.

Bacterial pathogens that are identified later in the course of CF airways disease include B cepacia complex, S maltophilia, and A xylosoxidans. Of these, B cepacia complex is the most serious because of its association with rapid progression to severe necrotising pneumonia and death.94,95 At least 10 distinctive genomovars of B cepacia have been identified and several have been named as distinct species ( LiPuma, personal communication).96 The genomovars most commonly associated with CF airway infections in Europe, North America and Australia include B cepacia (genomovar I), B multivorans (genomovar II), B cenocepacia (genomovar III), B stabilis (genomovar IV), B vietnamiensis (genomovar V), B dolosa (genomovar VI), and B ambifaria (genomovar VII).97,98,99,100 The vast majority of CF airway infections with B cepacia complex are caused by B multivorans (genomovars II), B cenocepacia (genomovar III) and B vietnamiensis (genomovar V).97 Although there are exceptions, most dramatically B dolosa, most of the severe infections and those associated with epidemic spread have been from B cenocepacia.101,102 Several clonal lineages are distributed widely across Europe and North America.97,101

S maltophilia and A xylosoxidans are seen more commonly than B cepacia complex in CF patients with advanced lung disease, but are generally less virulent. Several epidemiological studies examining their association with morbidity and mortality in CF have not shown a correlation between infection and outcome.50,103

Antibiotic resistance

Susceptibility testing of CF isolates of P aeruginosa is difficult for many of the same reasons that affect organism isolation and identification. Slow growth and mucoidy may affect the usefulness of automated systems for susceptibility testing of P aeruginosa as well as for organism identification.59,60 When compared with broth microdilution, agar diffusion methods including disc diffusion (Kirby‐Bauer) and Etest performed well for most of the antibiotics tested.104

Early infections with P aeruginosa are commonly susceptible to anti‐pseudomonal β‐lactam antibiotics (including ticarcillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, cefoperazone, and the carbopenems), the aminoglycosides and the fluoroquinolones. However, as patients age, antibiotic resistance appears more frequently. At Danish CF centres a significant increase in resistance to β‐lactams was seen over two decades, but no correlation was found between the increase in minimal inhibitory concentration and the number of courses of anti‐pseudomonal treatment.105 Multiple antibiotic resistance, defined as in vitro susceptibility to only a single class of antimicrobial agents, has been reported in up to 11.6% of P aeruginosa isolates from individuals with CF in the USA.64 Data from Italian CF centres found that 17.4% of P aeruginosa isolates were multiply resistant.106 These multiply resistant isolates present an important management problem to clinicians. In order to help identify active antibiotic treatment for patients with multiresistant isolates, non‐standard methods of susceptibility including synergy testing and multiple combination bactericidal testing (MCBT) have been developed to test two and three drug combinations.107,108 These methods are being used by CF clinicians to guide treatment. However, a recent prospective study examining the clinical efficacy of MCBT for directing antibiotic treatment in 132 CF subjects with pulmonary exacerbations did not result in improved clinical or microbiological outcomes.109 Interestingly, even standard susceptibility testing has not been clearly shown to improve patient outcome.110 More recently, evidence of biofilm formation by organisms in the CF airway has prompted the investigation of biofilm susceptibility testing.111,112 Different drugs and drug combinations appear to be efficacious against P aeruginosa growing in biofilms; this may help to explain non‐bactericidal mechanisms of activity of antimicrobial treatment.

While clinical laboratories have not been routinely looking for methicillin resistance in S aureus isolated from patients with CF, a survey of isolates from a number of CF centres in the USA suggested that the rate of resistance in CF is comparable to that in the general population.64 Recent data from the US CF Foundation found that 14.6% of S aureus was methicillin resistant.83 Vancomycin tolerance and resistance have both been described in human isolates of S aureus,113 and it is likely that they will also be seen in individuals with CF as they become more common.

B cepacia complex organisms are often highly antibiotic resistant. All are intrinsically resistant to the aminoglycosides114 and the rate of in vitro resistance to the β‐lactam antibiotics, with the exception of meropenem, is also quite high.115,116 The quinolones have variable activity, but resistance can be readily induced.115 In vitro susceptibility testing suggests that there are combinations of antibiotics that act synergistically against B cepacia complex using either synergy testing or MBCT.116,117 Synergy testing, using two drug combinations, found that no active combination could be identified for 57% of isolates tested.117 The most active combinations were chloramphenicol plus minocycline (49% of isolates) and chloramphenicol plus ceftazidime (26% of isolates). MBCT testing using two or three drug combinations determined that at least one combination could be identified for all isolates tested.108 The majority of active combinations included meropenem. Unfortunately, it was not possible to predict for a given isolate whether a drug combination would be synergistic, additive or antagonistic.

Other antibiotic resistant Gram‐negative CF isolates include S maltophilia and A xylosoxidans. Treatment of these organisms is often complicated by resistance to the aminoglycosides and variable susceptibility to the β‐lactams and quinolones. The most active single drugs in vitro against S maltophilia are ticarcillin/clavulanate and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; the most active combination in synergy studies is ticarcillin/clavulanate plus aztreonam.118 In a study of 106 CF isolates of A xylosoxidans, the most active drugs were imipenem (59% susceptible), piperacillin/tazobactam (55%), meropenem (51%) and minocycline (51%).119 The most active additive or synergistic combinations were chloramphenicol plus minocycline, ciprofloxacin plus imipenem, and ciprofloxacin plus meropenem.

Conclusions

Research regarding pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis continues to evolve, generating new hypotheses regarding the pathophysiology of CF and improving our understanding of the natural history of the disease in patients with CF. Pulmonary exacerbations continue to have a significant impact on the lives of children and adults with CF. Improving our understanding of these events will have implications for basic research and clinical research in CF. Although much has been learned about pulmonary exacerbations in CF, the most problematic areas of research continue to be our limited understanding of the basic pathophysiology of these events and the need for clear consensus diagnostic criteria.

Abbreviations

ARIC - Acute Respiratory Illness Checklist

CF - cystic fibrosis

CFTR - cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator

FEV1 - forced expiratory volume in 1 s

IL - interleukin

MCBT - multiple combination bactericidal testing

RSSQ - Respiratory and Systemic Symptoms Questionnaire

TNFα - tumour necrosis factor α

Footnotes

Support: Leroy Matthew Physician Scientist, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; NIH (NHBLI) 1 K23 HL72017‐01 (CG).

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Ferkol T, Rosenfeld M, Milla C E. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations. J Pediatr 2006148259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boucher R C. New concepts of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur Respir J 200423146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Randell S H, Boucher R C. Effective mucus clearance is essential for respiratory health. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 20063520–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mall M, Grubb B R, Harkema J R.et al Increased airway epithelial Na+ absorption produces cystic fibrosis‐like lung disease in mice. Nat Med 200410487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaldson S H, Bennett W D, Zeman K L.et al Mucus clearance and lung function in cystic fibrosis with hypertonic saline. N Engl J Med 2006354241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elkins M R, Robinson M, Rose B R.et al A controlled trial of long‐term inhaled hypertonic saline in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2006354229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joo N S, Irokawa T, Wu J V.et al Absent secretion to vasoactive intestinal peptide in cystic fibrosis airway glands. J Biol Chem 200227750710–50715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joo N S, Lee D J, Winges K M.et al Regulation of antiprotease and antimicrobial protein secretion by airway submucosal gland serous cells. J Biol Chem 200427938854–38860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joo N S, Irokawa T, Robbins R C.et al Hyposecretion, not hyperabsorption, is the basic defect of cystic fibrosis airway glands. J Biol Chem 20062817392–7398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiatt P W, Grace S C, Kozinetz C A.et al Effects of viral lower respiratory tract infection on lung function in infants with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics 1999103619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piedra P A, Grace S, Jewell A.et al Purified fusion protein vaccine protects against lower respiratory tract illness during respiratory syncytial virus season in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 19961523–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piedra P A, Cron S G, Jewell A.et al Immunogenicity of a new purified fusion protein vaccine to respiratory syncytial virus: a multi‐center trial in children with cystic fibrosis. Vaccine 2003212448–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regelmann W E, Elliott G R, Warwick W J.et al Reduction of sputum Pseudomonas aeruginosa density by antibiotics improves lung function in cystic fibrosis more than do bronchodilators and chest physiotherapy alone. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990141914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith A L, Redding G, Doershuk C.et al Sputum changes associated with therapy for endobronchial exacerbation in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 1988112547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wat D, Doull I. Respiratory virus infections in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev 20034172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Ewijk B E, van der Zalm M M, Wolfs T F.et al Viral respiratory infections in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 20054(Suppl 2)31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsey B W, Pepe M S, Quan J M.et al Intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. Cystic Fibrosis Inhaled Tobramycin Study Group. N Engl J Med 199934023–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aaron S D, Ramotar K, Ferris W.et al Adult cystic fibrosis exacerbations and new strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004169811–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konstan M W, Walenga R W, Hilliard K A.et al Leukotriene B4 markedly elevated in the epithelial lining fluid of patients with cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993148896–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konstan M W, Hilliard K A, Norvell T M.et al Bronchoalveolar lavage findings in cystic fibrosis patients with stable, clinically mild lung disease suggest ongoing infection and inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994150448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonfield T L, Panuska J R, Konstan M W.et al Inflammatory cytokines in cystic fibrosis lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19951522111–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sagel S D, Kapsner R, Osberg I.et al Airway inflammation in children with cystic fibrosis and healthy children assessed by sputum induction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20011641425–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ordonez C L, Henig N R, Mayer‐Hamblett N.et al Inflammatory and microbiologic markers in induced sputum after intravenous antibiotics in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20031681471–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colombo C, Costantini D, Rocchi A.et al Cytokine levels in sputum of cystic fibrosis patients before and after antibiotic therapy. Pediatr Pulmonol 20054015–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuchs H J, Borowitz D S, Christiansen D H.et al Effect of aerosolized recombinant human DNase on exacerbations of respiratory symptoms and on pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis. The Pulmozyme Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994331637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibson R L, Emerson J, McNamara S.et al Significant microbiological effect of inhaled tobramycin in young children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003167841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saiman L, Marshall B C, Mayer‐Hamblett N.et al Azithromycin in patients with cystic fibrosis chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 20032901749–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsey B W, Boat T F. Outcome measures for clinical trials in cystic fibrosis. Summary of a Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus conference. J Pediatr 1994124177–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall B C. Pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis: it's time to be explicit! Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004169781–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Microbiology and infectious disease in cystic fibrosis: V (Section 1). Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 1994

- 31.Johnson C, Butler S M, Konstan M W.et al Factors influencing outcomes in cystic fibrosis: a center‐based analysis. Chest 200312320–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dakin C, Henry R L, Field P.et al Defining an exacerbation of pulmonary disease in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 200131436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenfeld M, Emerson J, Williams‐Warren J.et al Defining a pulmonary exacerbation in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 2001139359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabin H R, Butler S M, Wohl M E.et al Pulmonary exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 200437400–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson T M, Donaldson G C, Hurst J R.et al Early therapy improves outcomes of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20041691298–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellaffi M, Vinsonneau C, Coste J.et al One‐year outcome after severe pulmonary exacerbation in adults with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005171158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Texereau J, Jamal D, Choukroun G.et al Determinants of mortality for adults with cystic fibrosis admitted in Intensive Care Unit: a multicenter study. Respir Res 2006714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobbin C J, Milross M A, Piper A J.et al Sequential use of oxygen and bi‐level ventilation for respiratory failure in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 20043237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sood N, Paradowski L J, Yankaskas J R. Outcomes of intensive care unit care in adults with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001163335–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vedam H, Moriarty C, Torzillo P J.et al Improved outcomes of patients with cystic fibrosis admitted to the intensive care unit. J Cyst Fibros 200438–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slieker M G, van Gestel J P, Heijerman H G.et al Outcome of assisted ventilation for acute respiratory failure in cystic fibrosis. Intensive Care Med 200632754–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liou T G, Adler F R, Fitzsimmons S C.et al Predictive 5‐year survivorship model of cystic fibrosis. Am J Epidemiol 2001153345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liou T G, Adler F R, Cahill B C.et al Survival effect of lung transplantation among patients with cystic fibrosis. JAMA 20012862683–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayer‐Hamblett N, Rosenfeld M, Emerson J.et al Developing cystic fibrosis lung transplant referral criteria using predictors of 2‐year mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20021661550–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liou T G, Adler F R, Huang D. Use of lung transplantation survival models to refine patient selection in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20051711053–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emerson J, Rosenfeld M, McNamara S.et al Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other predictors of mortality and morbidity in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 20023491–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marshall B C, Butler S M, Stoddard M.et al Epidemiology of cystic fibrosis‐related diabetes. J Pediatr 2005146681–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Britto M T, Kotagal U R, Hornung R W.et al Impact of recent pulmonary exacerbations on quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest 200212164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobbin C J, Bartlett D, Melehan K.et al The effect of infective exacerbations on sleep and neurobehavioral function in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200517299–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goss C H, Otto K, Aitken M L.et al Detecting Stenotrophomonas maltophilia does not reduce survival of patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002166356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goss C H, Rubenfeld G D, Otto K.et al The effect of pregnancy on survival in women with cystic fibrosis. Chest 20031241460–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goss C H, Mayer‐Hamblett N, Aitken M L.et al Association between Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and lung function in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 200459955–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schechter M S, Shelton B J, Margolis P A.et al The association of socioeconomic status with outcomes in cystic fibrosis patients in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20011631331–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goss C H, Newsom S A, Schildcrout J S.et al Effect of ambient air pollution on pulmonary exacerbations and lung function in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004169816–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brody A S, Sucharew H, Campbell J D.et al Computed tomography correlates with pulmonary exacerbations in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20051721128–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith J A, Owen E C, Jones A M.et al Objective measurement of cough during pulmonary exacerbations in adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 200661425–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiska D L, Kerr A, Jones M C.et al Accuracy of four commercial systems for identification of Burkholderia cepacia and other gram‐negative nonfermenting bacilli recovered from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 199634886–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shelly D B, Spilker T, Gracely E J.et al Utility of commercial systems for identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex from cystic fibrosis sputum culture. J Clin Microbiol 2000383112–3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saiman L, Burns J L, Larone D.et al Evaluation of MicroScan Autoscan for identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol 200341492–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burns J L, Saiman L, Whittier S.et al Comparison of two commercial systems (Vitek and MicroScan‐WalkAway) for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 200139257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong K, Roberts M C, Owens L.et al Selective media for the quantitation of bacteria in cystic fibrosis sputum. J Med Microbiol 198417113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carson L A, Tablan O C, Cusick L B.et al Comparative evaluation of selective media for isolation of Pseudomonas cepacia from cystic fibrosis patients and environmental sources. J Clin Microbiol 1988262096–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Henry D A, Campbell M E, LiPuma J J.et al Identification of Burkholderia cepacia isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis and use of a simple new selective medium. J Clin Microbiol 199735614–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burns J L, Emerson J, Stapp J R.et al Microbiology of sputum from patients at cystic fibrosis centers in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 199827158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitby P W, Carter K B, Burns J L.et al Identification and detection of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia by rRNA‐ directed PCR. J Clin Microbiol 2000384305–4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu L, Coenye T, Burns J L.et al Ribosomal DNA‐directed PCR for identification of Achromobacter (Alcaligenes) xylosoxidans recovered from sputum samples from cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol 2002401210–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coenye T, Vandamme P, LiPuma J J. Infection by Ralstonia species in cystic fibrosis patients: identification of R pickettii and R mannitolilytica by polymerase chain reaction. Emerg Infect Dis 20028692–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qin X, Emerson J, Stapp J.et al Use of real‐time PCR with multiple targets to identify Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other nonfermenting gram‐negative bacilli from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 2003414312–4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Armstrong D S, Grimwood K, Carlin J B.et al Bronchoalveolar lavage or oropharyngeal cultures to identify lower respiratory pathogens in infants with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 199621267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosenfeld M, Emerson J, Accurso F.et al Diagnostic accuracy of oropharyngeal cultures in infants and young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 199928321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kabra S K, Alok A, Kapil A.et al Can throat swab after physiotherapy replace sputum for identification of microbial pathogens in children with cystic fibrosis? Indian J Pediatr 20047121–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De B K, Alifier M, Vandeputte S. Sputum induction in young cystic fibrosis patients. Eur Respir J 20001691–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Henig N R, Tonelli M R, Pier M V.et al Sputum induction as a research tool for sampling the airways of subjects with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 200156306–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suri R, Marshall L J, Wallis C.et al Safety and use of sputum induction in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 200335309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ho S A, Ball R, Morrison L J.et al Clinical value of obtaining sputum and cough swab samples following inhaled hypertonic saline in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 20043882–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Armstrong D S, Grimwood K, Carlin J B.et al Lower airway inflammation in infants and young children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 19971561197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lyczak J B, Cannon C L, Pier G B. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 200215194–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fitzsimmons S C. The changing epidemiology of cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 19931221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ratjen F, Comes G, Paul K.et al Effect of continuous antistaphylococcal therapy on the rate of P aeruginosa acquisition in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 20013113–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stutman H R, Lieberman J M, Nussbaum E.et al Antibiotic prophylaxis in infants and young children with cystic fibrosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr 2002140299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rosenfeld M, Gibson R L, McNamara S.et al Early pulmonary infection, inflammation, and clinical outcomes in infants with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 200132356–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barker A F. Bronchiectasis. N Engl J Med 20023461383–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry 2004 Annual Data Report. p. 2005.

- 84.Demko C A, Byard P J, Davis P B. Gender differences in cystic fibrosis: Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J Clin Epidemiol 1995481041–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nixon G M, Armstrong D S, Carzino R.et al Clinical outcome after early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr 2001138699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kosorok M R, Zeng L, West S E.et al Acceleration of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis after Pseudomonas aeruginosa acquisition. Pediatr Pulmonol 200132277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li Z, Kosorok M R, Farrell P M.et al Longitudinal development of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and lung disease progression in children with cystic fibrosis. JAMA 2005293581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hancock R E, Mutharia L M, Chan L.et al Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis: a class of serum‐sensitive, nontypable strains deficient in lipopolysaccharide O side chains. Infect Immun 198342170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Luzar M A, Montie T C. Avirulence and altered physiological properties of cystic fibrosis strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun 198550572–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ernst R K, Yi E C, Guo L.et al Specific lipopolysaccharide found in cystic fibrosis airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science 19992861561–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thomas S R, Ray A, Hodson M E.et al Increased sputum amino acid concentrations and auxotrophy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in severe cystic fibrosis lung disease. Thorax 200055795–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burns J L, Gibson R L, McNamara S.et al Longitudinal assessment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in young children with cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis 2001183444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Drenkard E, Ausubel F M. Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature 2002416740–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thomassen M J, Demko C A, Klinger J D.et al Pseudomonas cepacia colonization among patients with cystic fibrosis. A new opportunist. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985131791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Isles A, Maclusky I, Corey M.et al Pseudomonas cepacia infection in cystic fibrosis: an emerging problem. J Pediatr 1984104206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.LiPuma J J. Update on the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Curr Opin Pulm Med 200511528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.LiPuma J J, Spilker T, Gill L H.et al Disproportionate distribution of Burkholderia cepacia complex species and transmissibility markers in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200116492–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Biddick R, Spilker T, Martin A.et al Evidence of transmission of Burkholderia cepacia, Burkholderia multivorans and Burkholderia dolosa among persons with cystic fibrosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 200322857–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kidd T J, Bell S C, Coulter C. Genomovar diversity amongst Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates from an Australian adult cystic fibrosis unit. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 200322434–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cunha M V, Leitao J H, Mahenthiralingam E.et al Molecular analysis of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates from a Portuguese cystic fibrosis center: a 7‐year study. J Clin Microbiol 2003414113–4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mahenthiralingam E, Vandamme P, Campbell M E.et al Infection with Burkholderia cepacia complex genomovars in patients with cystic fibrosis: virulent transmissible strains of genomovar III can replace Burkholderia multivorans. Clin Infect Dis 2001331469–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kalish L A, Waltz D A, Dovey M.et al Impact of Burkholderia dolosa on lung function and survival in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006173421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tan K, Conway S P, Brownlee K G.et al Alcaligenes infection in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 200234101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Burns J L, Saiman L, Whittier S.et al Comparison of agar diffusion methodologies for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol 2000381818–1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ciofu O, Giwercman B, Pedersen S S.et al Development of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa during two decades of antipseudomonal treatment at the Danish CF Center. APMIS 1994102674–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Taccetti G, Campana S, Marianelli L. Multiresistant non‐fermentative gram‐negative bacteria in cystic fibrosis patients: the results of an Italian multicenter study. Italian Group for Cystic Fibrosis microbiology. Eur J Epidemiol 19991585–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Saiman L, Mehar F, Niu W W.et al Antibiotic susceptibility of multiply resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis, including candidates for transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 199623532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lang B J, Aaron S D, Ferris W.et al Multiple combination bactericidal antibiotic testing for patients with cystic fibrosis infected with multiresistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20001622241–2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Aaron S D, Vandemheen K L, Ferris W.et al Combination antibiotic susceptibility testing to treat exacerbations of cystic fibrosis associated with multiresistant bacteria: a randomised, double‐blind, controlled clinical trial. Lancet 2005366463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Smith A L, Fiel S B, Mayer‐Hamblett N.et al Susceptibility testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates and clinical response to parenteral antibiotic administration: lack of association in cystic fibrosis. Chest 20031231495–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Aaron S D, Ferris W, Ramotar K.et al Single and combination antibiotic susceptibilities of planktonic, adherent, and biofilm‐grown Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates cultured from sputa of adults with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 2002404172–4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Moskowitz S M, Foster J M, Emerson J.et al Clinically feasible biofilm susceptibility assay for isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 2004421915–1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Appelbaum P C. The emergence of vancomycin‐intermediate and vancomycin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect 200612(Suppl 1)16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Moore R A, Hancock R E. Involvement of outer membrane of Pseudomonas cepacia in aminoglycoside and polymyxin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 198630923–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lewin C, Doherty C, Govan J. In vitro activities of meropenem, PD 127391, PD 131628, ceftazidime, chloramphenicol, co‐trimoxazole, and ciprofloxacin against Pseudomonas cepacia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 199337123–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Aaron S D, Ferris W, Henry D A.et al Multiple combination bactericidal antibiotic testing for patients with cystic fibrosis infected with Burkholderia cepacia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20001611206–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Burns J L, Saiman L. Burkholderia cepacia infections in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 199918155–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Krueger T S, Clark E A, Nix D E. In vitro susceptibility of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia to various antimicrobial combinations. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 20014171–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Saiman L, Chen Y, Tabibi S.et al Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of Alcaligenes xylosoxidans isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 2001393942–3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]