Abstract

Considered from medical, social or economic perspectives, the cost of musculoskeletal injuries experienced in the workplace is substantial, and there is a need to identify the most efficacious interventions for their effective prevention, management and rehabilitation. Previous reviews have highlighted the limited number of studies that focus on upper extremity intervention programmes. The aim of this study was to evaluate the findings of primary, secondary and/or tertiary intervention studies for neck/upper extremity conditions undertaken between 1999 and 2004 and to compare these results with those of previous reviews. Relevant studies were retrieved through the use of a systematic approach to literature searching and evaluated using a standardised tool. Evidence was then classified according to a “pattern of evidence” approach. Studies were categorised into subgroups depending on the type of intervention: mechanical exposure interventions; production systems/organisational culture interventions and modifier interventions. 31 intervention studies met the inclusion criteria. The findings provided evidence to support the use of some mechanical and modifier interventions as approaches for preventing and managing neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions and fibromyalgia. Evidence to support the benefits of production systems/organisational culture interventions was found to be lacking. This review identified no single‐dimensional or multi‐dimensional strategy for intervention that was considered effective across occupational settings. There is limited information to support the establishment of evidence‐based guidelines applicable to a number of industrial sectors.

One of the major problems facing industrial countries is work‐related musculoskeletal disorders.1 Recent literature suggests that the incidence of such injuries may continue to rise owing to increased exposure to workplace risk factors,2 more segmented and repetitive work, increased mechanisation and shifts in working practices towards the service and information sector.3

There are direct health costs associated with the rehabilitation of workers with musculoskeletal injuries, and also significant economic costs are imposed on the industry as a result of compensation, lost productivity and retraining.4 The magnitude of the problem in financial terms has been estimated in the US to be as much as US$54 billion per year.1

Workers affected by work‐related musculoskeletal disorders are often afflicted by long‐term pain, loss of function and disability. For the effective prevention and management of such disorders, national organisations (eg, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, USA; Health and Safety Executive, UK; Occupational Safety and Health, New Zealand) have often implemented a variety of single‐dimensional and multi‐dimensional programmes involving medical, physical and psychosocial interventions. As intervention approaches within an industrial setting are often complex and evolving, they require evidenced‐based models to be effective.1

Any evaluation of the potential benefits of interventions is difficult. However, the work of Westgaard and Winkel5 provides a model for the classification of interventions, thereby allowing a review of the literature to be undertaken in a structured manner. Westgaard and Winkel5 categorised intervention strategies into three main groups: mechanical exposure, production systems/organisational culture and modifier interventions. Mechanical exposure interventions typically focus on changing the design of tools, such as the computer mouse or keyboard. Production systems interventions, however, generally implement changes to the material production and/or the organisational culture of a company. The latter may involve team building and increased worker participation in the problem‐solving of workplace production (ie, participatory ergonomics). Finally, interventions that incorporate specific training of workers to manage exposure levels to physical and psychosocial stressors are termed modifier interventions. These may involve an exercise programme and/or ergonomic education.

Previous reviews have highlighted a dearth of literature examining the effectiveness of intervention approaches for the prevention and management of neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions.6,7,8,9 Furthermore, many of the experimental studies included in these reviews have been of low quality and few have included randomised controlled trials (RCT). Thus, the opportunity to establish effective evidence‐based management programmes for work‐related musculoskeletal disorders has been restricted. Therefore, there is a need to update our current knowledge using a systematic approach. The aim of this study was to fulfil this need by conducting a systematic review and evaluation of the findings of primary/secondary and/or tertiary intervention studies for neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions undertaken between 1999 and 2004.

Methods

Search strategy

An initial search of the literature integrated a variety of sources including textbooks and conference proceedings, national and international health and safety organisation websites, and a general internet search. From this initial search, an extensive keyword list was developed to incorporate nationally and internationally recognised work‐related musculoskeletal terms and definitions (eg, musculoskeletal disorder, repetitive strain injuries and occupational overuse syndrome), inclusive of diagnostic conditions (eg, thoracic outlet syndrome and cubital tunnel syndrome). Keywords specific to intervention studies were generated, which used a combination of generic labels (eg, musculoskeletal control and ergonomic intervention) and specific intervention approaches (eg, workstation design, job rotation and physical training).

Four researchers (BA, MGB, JC and MS), guided by a library and information manager, carried out the literature search. The keyword list and all combinations of keywords were used uniformly by all four researchers to ensure a standardised approach to the search procedure. An initial check of the keyword list was made against each of the subject headings from 15 electronic databases (CINAHL (including Cochrane Reviews); EBSCO Megafile Premier (including Medline, Health Source: Consumer Edition and Nursing/Academic Edition); Embase; Ergonomics Abstracts; Index NZ; AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine); Annual reviews; Psych INFO (including PsycARTICLES); ProQuest 5000 (including ProQuest Health and Medical Complete); Expanded Academic ASAP; Sports Discus; Science Direct; Blackwell Synergy; Lippincott 100; OSH Reference Collection (including OSHLINE with NIOSHTIC and NIOSHTIC2)). An examination of review articles (unrestricted by date of publication), as well as the personal libraries of the contributing authors, was undertaken to identify further studies. Personal communications with national and international representatives or experts within the field of musculoskeletal conditions were also made. Where appropriate, additional keywords were added and modifications made to the keyword list.

The final search involved the previously mentioned 15 electronic databases and an examination of the bibliographies of recent review papers. To ensure that only high‐quality papers were included within the current literature review, strict inclusion/exclusion criteria were adopted. These criteria were based on previous major reviews in this subject area (Bernard10).

Inclusion criteria

Published within the past 5 years (Jan 1999–Oct 2004).

Participation rate ⩾70%.

Health outcomes defined by symptoms and/or well‐documented questionnaires and/or physical examination.

The body part in question was subjected to an independent exposure assessment—that is, direct observation or actual measurement of exposure.

Musculoskeletal conditions of the neck, shoulder, elbow and hand/wrist (neck/upper extremities).

Duration of subject follow‐up ⩾2 months.

Sufficient documentation of intervention and intervention process.

English language publications.

Exclusion criteria

Back pain and lower extremity injuries.

Laboratory‐based studies.

Clinical treatment of musculoskeletal disorders.

Clinically based modifier interventions such as pharmacological treatment, splinting, acupuncture and physiotherapy or chiropractic treatment.

Quality assessment and grading of studies

The critical appraisal and grading of studies involved the use of the generic appraisal tool for epidemiology (GATE): appraisal modules (effective practice, informatics and quality improvement).11 This tool focused specifically on issues of study validity, quality of the study, the measure of occurrence, effect and precision of the study results and external validity.

After completion of the GATE checklists for intervention studies, papers were graded according to the quality of the study using a modified version of the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Injuries Group scoring system, in conjunction with the GATE tool, to provide an overall score for each study.12 The modified Cochrane Musculoskeletal Injuries Group scoring system comprised 13 separate questions graded between 0 and 2, covering aspects of study design and outcome measures. A final overall score (quality rating), out of a possible 26, was awarded to each intervention paper. Once each study had been assigned a rating score, it was graded according to a three‐point rating scale: low, medium or high. The cut‐off points for each level of grading were based on the overall distribution of scores across the intervention studies: <10 = “low”‐quality study; ⩾10<19 = “medium”‐quality study; ⩾19 = “high”‐quality study.

Six reviewers (BA, MGB, JC, PJL, PJM and MS) were trained in the review and scoring protocols. Two reviewers scored each paper independently, and if any discrepancy was found between their scores a third person reviewed the paper to reach a consensus.

Evidence classification

A “pattern of evidence” approach for classifying the level of evidence attached to intervention studies was adopted.1 The terminology and criteria used to define these levels of evidence were adapted from previous review papers6,7,10,13,14,15 and modified according to the quality assessment procedure adopted by this review (table 1). The overall level of evidence (ie, strong, moderate, some or insufficient) was then based on the number of studies, study design and the quality rating ascribed to that study.

Table 1 Level of evidence for evaluating the importance of intervention studies in the management of neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions.

| Level of evidence | Definition |

|---|---|

| Strong | When provided by generally consistent findings in multiple RCTs of high quality (QR⩾19) |

| Moderate | When provided by generally consistent findings in one RCT of high quality (QR⩾19) and in one or more RCTs of moderate or low quality, or by generally consistent findings in multiple RCTs of moderate quality (QR<19⩾10). |

| Some | When limited evidence, with only one RCT (any quality rating). Some findings of a positive relationship between exposure to the intervention and WRMD in one cohort or case–referent study, or consistent findings in multiple cross‐sectional studies, of which at least one study was of medium quality (QR⩾10<14) |

| Insufficient | All other cases (ie, consistent findings in multiple low‐quality (QR<10) cross‐sectional studies, or inconsistent findings in multiple studies) or findings of only one cross‐sectional study, irrespective of the quality of the study |

QR, quality rating; RCTs, randomised controlled trials; WRMD, work‐related musculoskeletal disorders.

Classification of intervention studies

Using a format similar to Westgaard and Winkel,5 studies in this review were categorised into subgroups depending on the type of intervention: mechanical exposure interventions, production systems/organisational culture interventions and modifier interventions. Interventions were also classified as primary, secondary and/or tertiary according to the definitions of the National Research Council1—that is, primary interventions before members of the population at risk having acquired a condition of concern; secondary interventions after occurrence of the condition within the population of concern and tertiary intervention strategies designed for individuals with chronically disabling conditions.

Results

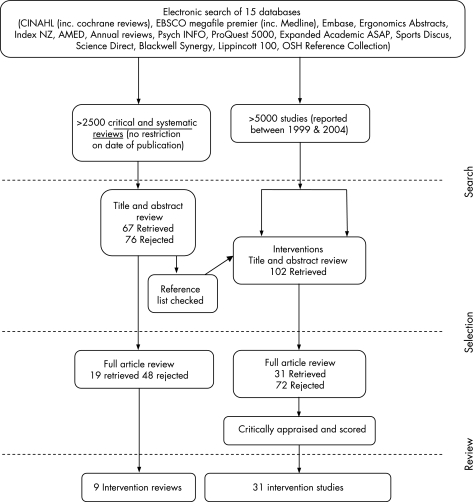

In excess of 5000 articles were identified from the initial search, of which 451 were suitable for abstract review; after a review of the abstracts, 102 intervention studies were considered. In total, 31 intervention studies were considered to have met the inclusion criteria and were suitable for full review (fig 1). Ten were classified as mechanical exposure interventions, two as production systems/organisational culture interventions and 19 as modifier interventions. On the basis of the type of mechanical intervention involved and the group of workers reported upon, it was possible to further classify mechanical interventions into three subgroups: (1) work environment/workstation adjustments and visual display unit (VDU) workers, (2) workstation equipment and VDU workers and (3) ergonomic equipment and manufacturing workers. Although no subgroups of production systems/organisational culture interventions could be identified, it was possible to group studies in the area of modifier interventions under six broad categories: (1) exercise and neck/upper extremity conditions; (2) exercise and fibromyalgia; (3) multiple modifier (including exercise) and neck/upper extremity conditions; (4) multiple modifier (including exercise) and fibromyalgia; (5) multiple modifier (excluding exercise) and neck/upper extremity conditions and (6) multiple modifier (excluding exercise) and fibromyalgia. Table 2 gives the tabulated information pertaining to each paper.

Figure 1 Overview of the literature search and review strategy.

Table 2 Summary of intervention studies.

| Intervention classification | Author | Design | Intervention | Measures | Findings | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design type | Type | Quality score | ||||

| Control group | Primary/secondary/tertiary | Quality rating | ||||

| Subjects | ||||||

| Diagnosis/condition | ||||||

| Mechanical exposure interventions | ||||||

| Work environment/workstation adjustments & VDU workers | Aaras et al (2001)16 | Prospective parallel group study Yes (without intervention) 150 VDU workers Visual discomfort, headache, neck, shoulder & forearm pain | New lighting, new workplaces and optometric corrections (when required) Primary | Pain intensity and duration VAS, Standardised Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire | Reduced shoulder pain No reduction in neck pain Unchanged forearm and hand pain | 11 Medium |

| Nevala‐Puranen et al (2003)17 | Pre‐/post‐cohort with parallel group randomised with respect to instruction No 20 VDU workers Neck, shoulder and upper limb pain | Modifications of office layout and workstation +/− ergonomic advice and upper limb exercises Secondary | VAS pain score Questionnaire: mental strain and physical exercise outside of work | Reduced upper limb VAS scores Improved work posture (shoulder flexion) Altered EMG activity during typing and the use of the mouse No differences between groups in work pace, change in mental strain at work or frequency of physical exercise | 10 Medium | |

| Mekhora et al (2000)18 | Randomised prospective parallel group study Yes (delayed intervention; subjects as own controls) 85 VDU workers Tension neck syndrome | Workstation adjustment using computer software application (IntelAd version 1.2) Secondary | Adapted Visual Analogue Discomfort Scale (VADS) Standardised Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire | Reduced VADS No difference between workload and work duration throughout study and/or between companies | 9 Low | |

| Ketola et al (2002)19 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (without intervention) 109 VDU workers Neck, shoulder and upper limb pain | Workstation adjustment &/or redesign following intensive ergonomic education Secondary | Finnish education system ergonomic rating scale Discomfort diary Modified Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire | Reductions in discomfort ratings at 2 months Improved ergonomic rating, intensive group greater than education or reference group | 12 Medium | |

| Workstation equipment & VDU workers | Aaras et al (2001)20 | Prospective parallel group study Yes (without intervention) 67 VDU workers Neck, shoulder & forearm pain | VDU work utilising the Anir computer mouse (intervention) versus a traditional mouse Secondary | VAS pain score Clinical examination | Reduced number of tender points in the neck and shoulder Reduced neck, shoulder, forearm, wrist and hand pain scores, 6, 12 months Reduced sick leave Reduced pain with flexion and side‐flexion passive ROM in cervical spine | 9 Low |

| Rempel et al (1999)21 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (without intervention; subjects matched) 24 keyboard operators (administrative assistants or technical writer/editors) Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) | Use of keyboard where the keys differed in their force‐displacement characteristics. Keyboard ‘A'–Protouch (Key Tronic Corporation). Keyboard ‘B'–MacPro Plus with 2‐ounce rubber domes (Key Tronic Corporation) Secondary/tertiary(?) | Self‐administered medical history questionnaire Symptom survey (VAS pain score) Questionnaire of hand‐function status Standardised physical examination Nerve conduction test | Difference in pain levels between the keyboard groups, 12 weeks; not at 6 weeks. Reduced pain at 12 weeks using keyboard ‘A' No differences in mean palm‐wrist median sensory latencies between 0 and 12 weeks No differences between groups in hand‐function ratings, 6 and 12 weeks | 20 High | |

| Tittiranonda et al (1999)22 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (placebo intervention; subjects matched) 4 groups, 20 keyboard operators in each Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) and/or tendonitis | 4 computer keyboards: standard (placebo), Apple Adjustable Keyboard (kb1), Comfort Keyboard System (kb2) and Microsoft Natural Keyboard (kb3) Secondary/tertiary(?) | Physical examination Hand/arm discomfort and pain questionnaire VAS of stiffness, numbness or pain Job Content Instrument (JCI) Work Interpersonal Relationships Inventory (WIRI) | Significant reduction in overall pain severity in kb3 at 6 months Significant increase in functional status after 6 months in kb3 group compared to placebo. No significant decrease in prevalence of clinical measures after 6 months | 18 Medium | |

| Ergonomic equipment & manufacturing workers | Herbert et al (2001)23 | Cohort study No N = 56 female Hispanic and Indian spooling workers at sequin manufacturing company Upper extremity Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs) | Ergonomic education and introduction of adjustable chair (including training in correct chair use) Primary/secondary | Symptoms portion of the 1993 NIOSH questionnaire Pre‐/Post video‐analysis of upper extremity postures using the Modified Exposure Assessment Method | Reduced pain scores after introduction of adjustable chairs at most anatomic sites Reduced prevalence of pain in the right shoulder, left elbow, and left forearm after introduction of adjustable chair. Improved upper limb posture following chair intervention | 8 Low |

| Aiba et al (1999)24 | Prospective longitudinal cohort No 383 manufacturing workers using impact wrenches Vibration White Finger (VWF) | Introduction of vibration‐damped wrench Primary | Stockholm Workshop Scale for VWF Questionnaires on work histories, medical histories and subjective symptoms, including VWF Medical doctor confirmed VWF by showing the subject a photograph of typical VWF conditions | Prevalence of VWF eliminated | 3 Low | |

| Jetzer et al (2003)25 | Cohort study No 165 manufacturers & installers of concrete roofing tiles Hand‐Arm Vibration Syndrome (HAVS) or CTS | Introduction of new tools with decreased levels of Hand‐Arm vibration exposure and/or ISO 10 819 gloves Primary | Questionnaire on medical and work history Clinical hand examination by occupational health nurses Vascular tests depending on responses to medical questionnaire and Stockholm Workshop Scale | Trend toward decreasing prevalence of HAVS Workers who used new low‐vibration tools and wore ISO 10 819 gloves showed most improvement and least decrement in symptoms | 6 Low | |

| Production systems/organisation culture interventions | ||||||

| Production systems/organisation culture intervention | Christmansson et al (1999)26 | Pre‐/post‐case‐studies No 17 window and door assembly workers Upper extremity pain disorders | Organisation alterations, control systems and work design (distribution of work tasks) Primary | Structured interviews Video analyses using Hand‐Arm‐Movement‐Analysis (HAMA) Psycho‐social questionnaires Medical examination | No improvement in prevalence of upper extremity MSDs during study period Some psychosocial factors improved (eg “influence on and control of work”), some worsened (eg “relationship with fellow workers”) | 4 Low |

| Fernstrom & Aborg (1999)27 | Cohort No 22 female office workers performing data entry tasks Neck, shoulder, arm and hand pain | Organisation alterations and different work tasks Primary/secondary | Clinical examination by physiotherapist Diagnoses according to a documented screening method Subjects videotaped throughout test days | No improvement in neck, shoulder and/or arm pain No difference in number or duration of rest periods between years Increased non‐computer work from 50 min in 1991 to 93 min in 1992 | 8 Low | |

| Modifier interventions | ||||||

| Exercise and upper extremity conditions | Ludewig and Borstad (2003) 28 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (without intervention and without conditions) 92 male construction workers performing overhead work Shoulder Impingement Syndrome | Stretching and progressive strength training programme Secondary/tertiary(?) | Self‐reported Shoulder Rating Questionnaire (SRQ) Modified Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) Questionnaire | Improvement in self‐reported Shoulder Rating Questionnaire (SRQ) and Shoulder Satisfaction Scores | 16 Medium |

| Hagberg et al (2000)29 | Randomised trial No 69 women industrial workers Cervico‐brachial syndrome ICD‐10 code M53.1 | Isometric shoulder endurance versus strength 16 week training programme Tertiary | VAS pain scores Sick leave & NSAID use Standarised physical examination Strength, range of motion and endurance tests | Reduced pain, no difference by training type No reduction in sick leave Improved arm motion performance test Increased shoulder strength | 14 Medium | |

| Waling et al (2002)30 | Prospective quasi‐randomised trial No 126 female administrative workers Trapezius Myalgia | Group training programmes: a) Strength group b) Endurance group c) Coordination group d) Stress management (non‐training) reference group Tertiary | VAS pain scores Frequency of pain Pressure pain thresholds Degree of worry Use of analgesics Sick leave | Reduced frequency of pain and VAS in all groups over time No change in pressure pain thresholds No differences between training groups and reference group on any variable | 12 Medium | |

| Exercise & Fibromyalgia | Meiworm et al (2000)31 | Experimental trial Yes (without intervention) 39, mostly females Fibromyalgia (FM) | 12 week progressive aerobic endurance exercise programme including walking, jogging, cycling and/or swimming Secondary/tertiary | Body diagram of pain VAS pain score Pressure pain thresholds | Decreased painful body area Reduced mean number of tender points Mean pain threshold unchanged VAS score unchanged No changes in control group | 10 Medium |

| Schachter et al (2003)32 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (without intervention) 143 females FM | Differing exercise duration: a) Long Bout of Exercise (LBE) b) Short Bout of Exercise (SBE) c) No exercise (NE) (control) Tertiary | Body pain diagrams AIMS2 Questionnaire Affect Scale Score Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) VAS pain score CPSS | Reduced disease severity and improved self‐efficacy within SBE group and compared to NE group Improvements in physical function, disease severity, symptoms, self‐efficacy and psychological well‐being in LBE group | 19 High | |

| Valim et al (2003)33 | Randomised trial No 76 females FM | Two exercise modalities: a) Aerobic exercise (AE) walking programme, b) Stretching exercise (SE) Tertiary | Sit and reach (flexibility) test Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) Short Form–36 (SF‐36) Question‐naire Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Trace‐State Anxiety Inventory Pain score from tender points VAS pain score | Improvements in AE group compared to SE group of total FIQ score and role emotional and mental health domains of FIQ, the mental component summary of SF‐36, BDI, VAS score and number of tender points No improvement in SE group in mental health or role emotional domains and the Mental Component Summary of the SF‐36 or BDI | 17 Medium | |

| van Santen et al (2002)34 | Pre‐/post‐test trial Yes (without intervention) 143 Females FM | Two intervention modalities: a) Group supervised fitness programme, (aerobic exercise and isometric strengthening) b) Biofeedback training for muscle relaxation Tertiary | VAS pain score VAS fatigue scale Health status: Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale, Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) Psychological distress: Symptom Checklist‐90‐Revised (SCL‐90) Physical fitness ‐ bicycle ergometer | No significant findings except physical fitness worsened for all groups over the study period. Decrease was less in fitness group compared to control group | 14 Medium | |

| Multiple modifier interventions (including exercise) & upper extremity conditions | de Greef et al (2003)35 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (without intervention) 53 Symphony Orchestra Musicians PRMDs | Specific mobilising, strengthening, and conditioning programme (the Groningen Exercise Therapy for Symphony Orchestra Musicians (GETSOM) programme) Secondary/tertiary(?) | Physical Competence Scale (PCS) World Health Questionnaire for Musicians (WHQM) | Musculoskeletal disorders decreased Perceived physical competence increased | 9 Low |

| Chan et al (2000)36 | Pre‐/post‐test trial No 12 Work‐related lateral epicondylitis of elbow | Education on pathology and ergonomics related to WRMDS, stretching & strengthening exercises to be performed at home and work hardening protocols Secondary/tertiary(?) | VAS pain scores LLUMC (Loma Linda University Medical Centre) Activity Sort Baltimore Therapeutic Equipment (BTE) Primus measures Dexter Evaluation Computer System Satisfaction with Performance Scaled Questionnaire | Reductions in pre/post VAS pain scores maintained at 4 and 12 week follow‐up Increased BTE Primus measures Increases in LLUMC Activity Sort Scores and Satisfaction with Performance Scaled Questionnaire Scores maintained at 4th and 12th weeks of follow‐up | 7 Low | |

| Omer et al (2003/2004)37 | Randomised controlled trial No true control group 50 VDU workers Cumulative Trauma Disorders (CTDs) including Myofascial Pain Syndrome (MPS) and Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) | Ergonomic and health education (‘control' group) versus an exercise programme (flexibility, RoM, relaxation, strengthening and postural exercises involving the neck shoulders and wrists performed 3 days per week at lunchtime) (treatment group) Secondary/tertiary(?) | Pain assessment using Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) Pain Disability Index (PDI) Tiredness Scale (TS) Beck Depression Inventory BDI) Scale | Improved NRS, PDI and BDI scores for treatment group | 9 Low | |

| van den Heuvel et al (2003)38 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (without intervention) 268 VDU workers Work‐related upper limb repetitive strain injuries according to the Health Council of the Netherlands | Microbreaks prompted by computer software and “natural” rest breaks versus microbreaks and natural rest breaks combined with the performance of regular exercises performed at the workstation also prompted by the software Secondary/tertiary(?) | Perceived overall recovery from complaints Frequency of complaints Severity of pain VAS scale Self‐reported sick leave Productivity | Self‐reported recovery higher in intervention group No differences between the groups for sick leave Improved productivity in Group 1 (breaks and no exercises) compared to control group Improved accuracy rate in intervention groups compared to control group | 13 Medium | |

| Multiple modifier interventions (including exercise) & Fibromyalgia | Bailey et al (1999)39 | Prospective pre‐/post‐cohort study No 106 FM | Fibro‐Fit Programme: 12‐week out‐patient exercise and multidisciplinary programme Tertiary | Fibro‐Fit self‐efficacy questionnaire Canadian Standardised Test of Fitness (CSTF) Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scales (F‐COPES) | Improvements in all outcome measures Relationship between smoking and pain. i.e. smokers had less improvement in pain Attendance rate of FM support group related to greater improvement in pain Patients who refused pain or anti‐depressant medications had poorer outcomes | 8 Low |

| Cedraschi et al (2004)40 | Pre‐/post‐test trial Yes (without intervention) 61 FM | Group training programme. Consisted of pool exercise, relaxation, low impact land exercise, activities of daily living and education. Tertiary | Number of tender points and myalgic score Global rating by physician Questionnaires | Improvement in Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) and Psychological General Well‐Being (PGWB) Index No change in objective physician measures | 14 Medium | |

| Gowans et al (1999)41 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (delayed intervention; subjects as own controls) 41 FM | 6‐week exercise and education programme (two exercise and two multidisciplinary educational sessions per week) Tertiary | Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) Arthritis Self‐Efficacy Scale (ASES) Knowledge of FM management Questionnaire 6 min walk test | Improvement in 6 min walk distance, well‐being, self‐efficacy, and FM knowledge Reduced morning fatigue All gains maintained at follow‐up except morning fatigue and subjects' knowledge of FM management which resumed to baseline levels | 11 Medium | |

| Mannerkorpi et al (2000)42 | Pre‐/post‐test trial No true control group used 69 females FM | Two intervention modalities: a) Group pool exercise programme b) Education programme Tertiary | Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) Short Form‐36 Questionnaire (SF‐36) Swedish Multi‐dimensional Pain Inventory (MPI‐S) Arthritis Self‐Efficacy Scale (ASES‐S) Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QOLS) | Improved FIQ score and walk distance compared with education group Improved FIQ physical functioning and anxiety scores in exercise compared with education group Improved Sf‐36 general health score, social functioning, pain severity and affective distress components of MPI‐S in exercise group Improved AIMS depression and QOLS in exercise compared to education group | 14 Medium | |

| Redondo et al (2004)43 | Prospective, longitudinal, quasi‐randomised, parallel trial No 40 females FM | Two intervention modalities: a) Physical Exercise (PE) and cardiovascular fitness programme b) Cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) Tertiary | Fibromyalgia Questionnaire (FIQ) Short Form‐36 (SF‐36) Beck Anxiety Inventory Chronic Pain Self‐Efficacy Scale (CPSS) Chronic Pain Coping Inventory Range of Motion and Pain scale | PE Group: Improvements in most items and total score of FIQ Improvement in the bodily pain domain of SF‐36 At one year follow‐up none of clinical variables were significantly better than the initial assessment CBT Group: Improved items of FIQ (stiffness, total score) at 8 weeks At 6 month and one year changes not maintained, except improved general health domains of SF‐36 EDUC group: symptoms and pain improved 0–6 weeks; returned to baseline 6–32 weeks | 16 Medium | |

| Multiple modifier interventions (excluding exercise) & upper extremity conditions | Faucett et al (2002)44 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (without intervention) 139 engineers and microscopic assembly workers of electronic manufacturing corporation Upper limb Work‐Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WRMSDs) | Muscle Learning Therapy (MLT) or educational group (EDUC) consisting of OHN‐delivered education and Cognitive Behavioural Training (CBT) that addressed symptom and stress management and problem solving Primary | Symptom Diary Data VAS pain measures Surface Electromyography (EMG) | MLT group: 0–6 weeks no change in symptoms and pain; 6–32 weeks worsened Control group: 0–6–32 weeks symptoms and pain steadily worsened Differences at 6 weeks significant, but not over all time periods | 10 Medium |

| Bohr (2000)45 | Randomised controlled trial No, comparison of two intervention groups 102 VDU workers Neck, shoulder and upper limb pain | Traditional ergonomic education versus participatory ergonomic education Primary | Paper and pencil surveys Observational checklists Standardised Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire Work AGPAR score | No difference between two groups for observation data scores for the work area configuration, worker postures, or overall scores No difference between two groups for upper body pain/discomfort or APGAR scores | 9 Low | |

| Multiple modifier interventions (excluding exercise) & Fibromyalgia | Oliver et al (2001)46 | Randomised controlled trial Yes (without intervention) 600 patients FM | Social support versus social support combined with health and self‐help education Tertiary | Health Care Costs Knowledge of FM ‘Guttman‐like' Group Cohesiveness Scale Adapted Arthritis Self‐Efficacy Scale | Reduced helplessness for participants in all groups but more markedly in social support and education group | 12 Medium |

Mechanical exposure interventions

Ten studies were classified as mechanical exposure interventions, and thereafter subdivided into three main groups as described previously. Within the subgroup of work environment/workstation adjustments (eg, modified lighting, new work place, office layout and software application) in VDU workers with neck/upper extremity conditions, four studies16,17,18,19 presented positive outcomes. Three were of medium quality,16,17,19 and included an RCT,19 whereas one study18 was of low quality. On the basis of the levels of evidence identified in table 1, it was concluded that there was some evidence for positive health effects after work environment/workstation adjustments in VDU workers with neck/upper extremity conditions.

Three studies20,21,22 that involved changes to workstation equipment (ie, keyboards and mouse design) in VDU workers with neck/upper extremity conditions reported positive outcomes resulting from these types of interventions. Rempel et al's21 and Tittiranonda et al's22 studies were RCTs of high and medium quality, respectively, while Arras et al's20 study was of low quality. Hence, there was moderate evidence to support this type of intervention.

Three studies23,24,25 that involved the introduction of ergonomic equipment (eg, adjustable chairs and vibration‐proof tools) for workers with neck/upper extremity conditions used in the manufacturing industry found positive health outcomes. However, all were rated as low quality. Thus, it was concluded that there was insufficient evidence for positive health effects resulting from this type of intervention.

Production systems/organisational culture

Two studies26,27 did not find improvements in health outcomes associated with organisational and work‐task design changes in office workers and manufacturing assembly workers; both studies were of low quality. Thus, there was insufficient evidence to support production systems/organisational intervention strategies.

Modifier interventions

Nineteen studies were classified under modifier interventions, and subsequently subclassified as described previously. Positive health outcomes were observed in three medium‐quality studies28,29,30 that examined the effects of exercise (eg, strength training, coordination and flexibility) in workers with neck/upper extremity conditions (excluding fibromyalgia). These studies included an RCT.28 Thus, it was concluded that there was some evidence that exercise has positive effects in workers with neck/upper extremity conditions.

Of the four studies31,32,33,34 that investigated the effects of exercise (ie, aerobic, flexibility and biofeedback for relaxation) in patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia, one study32 was rated as high quality and three31,33,34 as medium quality. Schachter et al32 and van Santen34 found no significant differences across control and experimental groups. Meiworm et al31 and Valim et al33 noted positive findings after the intervention, although a control group was lacking in the latter study. Overall, it was concluded that there was some evidence in support of the use of exercise as an intervention for managing patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

One RCT of medium quality38 and three of low quality35,36,37 provided some evidence that multiple modifier interventions including exercise (ie, rest‐breaks, Getsom programme, education and strengthening) can have positive effects in workers with neck/upper extremity conditions (excluding fibromyalgia). Furthermore, four medium‐quality studies40,41,42,43 that included an RCT,41 and one low‐quality study39, provided some evidence that multiple modifier interventions including exercise (ie, land and pool exercises, relaxation, education and cognitive behavioural therapy) can have positive effects in workers with fibromyalgia.

An RCT of medium quality,44 which examined multiple modifier interventions excluding exercise (ie, cognitive behavioural training and education), showed positive effects for workers with neck/upper extremity conditions (excluding fibromyalgia). By contrast, one low‐quality study45 examining education found no significant effects. Therefore, there was some evidence to support the use of this strategy. With respect to multiple modifier interventions excluding exercise (ie, social support and education) for workers with fibromyalgia, there was insufficient evidence from an RCT in a medium‐quality study46 to support this strategy.

Discussion

This review embodied the principles of a systematic review. Although some authors have suggested that an important facet of a systematic review might be to include a meta‐analysis,47 this was not considered appropriate for this review due to the heterogeneity of study designs, the general poor quality of studies and the diversity of exposure and outcome measures reported.

This review attempted to classify interventions according to whether they were primary, secondary or tertiary. Most studies were considered to involve secondary and/or tertiary interventions, although the type of intervention was often difficult to determine or not clearly stated, particularly for tertiary interventions (ie, studies often failed to define chronically disabling conditions). In most cases, tertiary interventions fell within the group of modifier interventions and, typically, involved subjects with fibromyalgia. Although some studies included both subjects with pain (ie, secondary intervention) and those without pain (ie, primary intervention), those without pain were rarely discussed independently within the results sections of the respective studies. These difficulties, combined with the heterogeneity of outcome measures, prevented direct comparisons between interventions or the evaluation of the efficacy of certain intervention types. Furthermore, where studies failed to make a clear distinction between subjects with and without pain, or to stratify their analysis according to the different participant groups, it is difficult to fully appreciate whether an intervention was benefiting one group of subjects more than another—for example, findings may well have been driven more by the prevention of new disorders than existing cases. The design of future studies should clearly define the purpose and population groups targeted, clearly documenting those participants who benefited most from the intervention.

To group intervention types and facilitate comparisons with previous reviews, the classification system proposed by Westgaard and Winkel5 was adopted. This classified interventions according to whether they were mechanical, production systems/organisation culture or modifier interventions. In some instances, further sub‐grouping of interventions was possible, thereby enabling interventions to be more closely aligned to specific industries, population groups and/or musculoskeletal conditions.

Mechanical interventions

Table 3 provides an overall summary of the effectiveness of mechanical interventions based on the findings of the current review and makes comparisons with those of previous reviews. The finding that there was some evidence for work environment/workstation adjustment for improved health outcomes in VDU workers with neck/upper extremity conditions was consistent with two previous reviews5,48 and similar to that of Verhagen et al.9 With respect to the latter review, it should be noted that different levels for indicating evidence were adopted and, on examination, their level denoted as “limited” can be considered similar to our level “some”.

Table 3 A comparison between the current and previous reviews for the level of evidence in support of mechanical interventions for neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions.

| Intervention condition/industry group | Evidence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Moderate | Some | Insufficient | |

| Mechanical exposure interventions | ||||

| Work environment/work station adjustments and VDU workers with neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions | * † † † | |||

| Work station equipment and VDU workers with neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions | * | † | † | |

| Work station equipment and manufacturing workers with neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions | * | |||

VDU, visual display unit.

*Current review.

†Previous reviews (NB: includes multiple findings from different reviews. As descriptions for ratings of evidence may have varied between review papers, these have been aligned with the current rating system based on the wording used).

In this study, there was moderate evidence that workstation equipment (mouse and keyboard design) can lead to positive health benefits in VDU workers with neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions. However, there was insufficient evidence for equipment interventions among manufacturing workers with neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions. Previous reviews have not delineated according to types of occupation. With respect to the findings for VDU workers, Williams et al8 reported a trend towards positive benefits for several workplace interventions associated with modifications to keyboard designs, while our findings showed stronger support for this intervention strategy. This difference may reflect the more objective approach to grading evidence used in this review. In contrast to our conclusions related to VDU workers were those of Verhagen et al,9 who found limited evidence for the efficacy of some keyboards in people with carpal tunnel syndrome. However, it should be noted that Verhagen et al9 reported that the RCT study by Tittiranonda et al22 provided no evidence to support modifications to keyboard design, a finding in contrast with our appraisal of the paper and also that of Williams et al.8

Production systems interventions

The finding of insufficient evidence for the benefits of production systems/organisation culture interventions was consistent with one previous review.5 Westgaard and Winkel5 identified seven Swedish production systems intervention studies and concluded that “this group of papers provided little evidence to suggest that improved health can be achieved through redesign of the production systems”.

The two production systems/organisation culture interventions26,27 identified in this review were of low quality, showed no improvements in outcome measures and involved non‐RCT. Although RCTs are considered the most powerful study design, ensuring randomisation and control within the workplace, particularly with respect to changes in production systems or the organisational culture within a company, is not always possible or ethical.1,49 This raises the question as to whether these types of interventions should be subjected to the same rigour as those used to evaluate the efficacy of mechanical or modifier interventions, and whether different criteria on which to base evidence classification should be adopted.

Modifier interventions

Table 4 provides an overall summary of the efficacy of modifier interventions based on the findings of the current review and also makes comparisons with the findings of previous reviews. Westgaard and Winkel5 concluded that modifier interventions involving the worker (eg, physical training) often achieve positive benefits. The current study concurred with these conclusions in that it found there was some evidence that exercise alone had positive effects in workers with neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions. This finding was similar to Verhagen et al,9 but in contrast to Williams et al8 who found insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of exercise programmes when managing neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions. With respect to Williams et al,8 only one paper with a low sample size and without a control group formed the basis of their conclusion. However, in this study, evidence was based on the findings from three medium‐quality studies, one of which was an RCT. With regard to fibromyalgia, some evidence for exercise interventions was found, although it should be noted that contrasting findings led to this conclusion. No other reviews have focused upon the effects of exercise and fibromyalgia.

Table 4 A comparison between the current and previous reviews for the level of evidence in support of modifier interventions for neck/upper extremity conditions.

| Intervention condition/industry group | Evidence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Moderate | Some | Insufficient | |

| Modifier interventions | ||||

| Exercise and neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions (excluding fibromyalgia) | * † † | † | ||

| Exercise and fibromyalgia | * | |||

| Multiple modifier interventions (including exercise) and neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions (excluding fibromyalgia) | * | † † | ||

| Multiple modifier interventions (including exercise) and fibromyalgia | * | † | ||

| Multiple modifier interventions (excluding exercise) and neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions (excluding fibromyalgia) | * | † † | ||

| Multiple modifier interventions (excluding exercise) and fibromyalgia | * † | |||

*Current review.

†Previous reviews (NB: includes multiple findings from different reviews. As descriptions for ratings of evidence may have varied between review papers, these have been aligned with the current rating system based on the wording used).

The current review found some evidence for multiple modifier interventions, inclusive and exclusive of exercise, in patients with neck/upper limb conditions. Such programmes included a combination of various types of low‐intensity group exercise training, education, relaxation techniques and/or cognitive behavioural therapy. A review by Karjalainen et al7 focused upon multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation studies and found insufficient evidence to support these programmes in the rehabilitation of adult patients with upper limb repetitive strain injuries. However, only two studies were reported upon in this review and these were published in 1994–5. Similarly, Verhagen et al9 concluded that there was a clear lack of evidence for multidisciplinary treatment. However, this conclusion was based on a single study, whereas the current review identified 12 studies examining multiple modifiers. Some evidence was found to support the use of multidisciplinary rehabilitation inclusive of exercise for fibromyalgia. Multiple modifier interventions exclusive of exercise were not effective in improving musculoskeletal health in patients with fibromyalgia, although there was an indication that some psychological factors, such as feelings of helplessness, may be improved. Similarly, Karjalainen et al14 considered the effects of multidisciplinary rehabilitation exclusive of exercise for fibromyalgia, reviewing seven studies of which four were of low quality, and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support these programmes.

Limitations of the review

Although this review included those studies that used well‐documented questionnaires for pain symptom outcomes, the validity and reliability of these measures could not always be determined. Unpublished studies, conference proceedings, reports and PhD theses were not reviewed. Reviewers were not blinded to authors or affiliations of published articles and, finally, the review was restricted to studies written in English.

Conclusion

This review identified no one single strategy for intervention that was considered effective for all types of industrial settings. The findings provided evidence to support the use of some mechanical and modifier interventions as approaches for the prevention and management of neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions and fibromyalgia. With respect to the latter, there was a distinct lack of well‐designed modifier intervention studies where the intervention was specifically tailored for the work environment and the tasks performed by the workers. Evidence to support the benefits of production systems/organisational culture interventions was lacking. These findings may be a reflection of the difficulty of undertaking studies within the workplace that include interventions focused upon health benefits compared with increased productivity and performance.

Overall, there seemed to be no clearly defined research strategy targeted at the identification of effective interventions specific to high‐risk industrial workers or individual neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions. At present, there are only isolated studies, often of low quality, that provide limited information for the establishment of new evidence‐based guidelines applicable across a number of industrial sectors. Future consideration should be given to a national/international research strategy plan targeted at specific groups (industries) or neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions. In this respect, a series of well‐designed, related projects will improve our understanding of the complexity of issues related to injury and occupational health management. Until then, we will continue to be faced with isolated research projects, the findings of which do not provide sufficient evidence for changing existing injury prevention and management practices.

Main messages

An international systematic review of contemporary literature (within the past 5 years) found 31 ergonomic interventions for the prevention and management of neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions

Findings support the use of some mechanical and modifier interventions for managing upper extremity conditions and fibromyalgia

Although evidence is lacking to support the benefits of production systems/organisational culture interventions, new quality criteria to replace that of blinding and randomisation may be necessary if the efficacy of these interventions is to be properly understood

Future consideration should be given to a national/international research strategy plan targeted at specific high‐risk industry groups and/or neck/upper extremity conditions.

Policy implications

Until such evidence is available, interventions for the prevention and management of neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions should continue to use multifactorial approaches

The use of production systems/organisational culture changes should not be viewed as a single specific intervention that will bring about improved outcomes in those workers with neck/upper extremity musculoskeletal conditions.

Acknowledgements

The financial support of the Accident Compensation Corporation of New Zealand in funding this research project is greatly appreciated. We acknowledge the valuable assistance and guidance of AUT's Information and Education Services, in particular Andrew South.

Abbreviations

GATE - generic appraisal tool for epidemiology

RCT - randomised controlled trials

VDU - visual display unit

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Panel on Musculoskeletal Disorders and the Workplace, Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine Musculoskeletal disorders and the workplace: low back and upper extremities. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 200117–37.

- 2.Buckle P, Devereux J.Work‐related neck and upper limb musculoskeletal disorders. Bilbao, Spain: European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 19997–10.

- 3.Yassi A. Repetitive strain injuries. Lancet 1997349943–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boden L I, Biddle E A, Spieler E A. Social and economic impacts of workplace illness and injury: current and future directions for research. Am J Ind Med 200140398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westgaard R H, Winkel J. Ergonomic intervention research for improved musculoskeletal health: a critical review. Int J Ind Ergon 199720463–500. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, van T M.et al Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for neck and shoulder pain among working age adults: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine 200126174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, van Tulder M.et al Biopsychosocial rehabilitation for upper limb repetitive strain injuries in working age adults (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 20043. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Williams R M, Westmorland M G, Schmuck G.et al Effectiveness of workplace rehabilitation interventions in the treatment of work‐related upper extremity disorders: a systematic review. J Hand Ther 200417267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verhagen A P, Bierma‐Zeinstra S M, Feleus A.et al Ergonomic and physiotherapeutic interventions for treating upper extremity work related disorders in adults (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 20043. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bernard B P.Musculoskeletal disorders and workplace factors: a critical review of epidemiologic evidence for work‐related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, upper extremity, and low back. Cincinnati: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), 19971–14.

- 11.EPIQ Generic Appraisal Tool for Epidemiology (GATE), Appraisal Modules.UoA, 2004. http://www.epiq.co.nz (accessed 2 Feb 2007)

- 12.Thomson L C, Handoll H H G, Cunningham A.et al Physiotherapist‐led programmes and interventions for rehabilitation of anterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament and meniscal injuries of the knee in adults (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 20044. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ariens G A, van Mechelen W, Bongers P M.et al Physical risk factors for neck pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 2000267–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, van Tulder M.et al Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for fibromyalgia and musculoskeletal pain in working age adults (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 20043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.O'Connor D, Marshall S, Massy‐Westropp N. Non‐surgical treatment (other than steroid injection) for carpal tunnel syndrome (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 20043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Aaras A, Horgen G, Bjorset H H.et al Musculoskeletal, visual and psychosocial stress in VDU operators before and after multidisciplinary ergonomic interventions. A 6 years prospective study—part II. Appl Ergon 200132559–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nevala‐Puranen N, Pakarinen K, Louhevaara V. Ergonomic intervention on neck, shoulder and arm symptoms of newspaper employees in work with visual display units. Int J Ind Ergon 2003311–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mekhora K, Liston C B, Nanthavanij S.et al The effect of ergonomic intervention on discomfort in computer users with tension neck syndrome. Int J Ind Ergon 200026367–379. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ketola R, Toivonen R, Hakkanen M.et al Effects of ergonomic intervention in work with video display units. Scand J Work Environ Health 20022818–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aaras A, Dainoff M, Ro O.et al Can a more neutral position of the forearm when operating a computer mouse reduce the pain level for visual display unit operators? A prospective epidemiological intervention study: part II. Int J Hum Comput Interact 20011313–40. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rempel D, Tittiranonda P, Burastero S.et al Effect of keyboard keyswitch design on hand pain. J Occup Environ Med 199941111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tittiranonda P, Rempel D, Armstrong T.et al Effect of four computer keyboards in computer users with upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Am J Ind Med 199935647–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herbert R, Dropkin J, Warren N.et al Impact of a joint labor‐management ergonomics program on upper extremity musculoskeletal symptoms among garment workers. Appl Ergon 200132453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aiba Y, Ohshiba S, Ishizuka H.et al Study on the effects of countermeasures for vibrating tool workers using an impact wrench. Ind Health 199937426–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jetzer T, Haydon P, Reynolds D. Effective intervention with ergonomics, antivibration gloves, and medical surveillance to minimize hand‐arm vibration hazards in the workplace. J Occup Environ Med 2003451312–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christmansson M, Friden J, Sollerman C. Task design, psycho‐social work climate and upper extremity pain disorders—effects of an organisational redesign on manual repetitive assembly jobs. Appl Ergon 199930463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernstrom E A, Aborg C M. Alterations in shoulder muscle activity due to changes in data entry organisation. Int J Ind Ergon 199923231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludewig P M, Borstad J D. Effects of a home exercise programme on shoulder pain and functional status in construction workers. Occup Environ Med 200360841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagberg M, Harms‐Ringdahl K, Nisell R.et al Rehabilitation of neck‐shoulder pain in women industrial workers: a randomized trial comparing isometric shoulder endurance training with isometric shoulder strength training. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000811051–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waling K, Javholm B, Sundelin G. Effects of training on female trapezius myalgia: an intervention study with a 3‐year follow‐up period. Spine 200227789–96 [With commentary by A Malmivaara].. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meiworm L, Jakob E, Walker U.et al Patients with fibromyalgia benefit from aerobic endurance exercise. Clin Rheumatol 200019253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schachter C L, Busch A J, Peloso P M.et al Effects of short versus long bouts of aerobic exercise in sedentary women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 200383340–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valim V, Oliveira L, Suda A.et al Aerobic fitness effects in fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2003301060–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Santen M, Bolwijn P, Verstappen F.et al A randomized clinical trial comparing fitness and biofeedback training versus basic treatment in patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 200229575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Greef M, van Wijck R, Reynders K.et al Impact of the Groningen exercise therapy for symphony orchestra musicians program on perceived physical competence and playing‐related musculoskeletal disorders of professional musicians. Med Probl Perform Art 200318156–160. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan C C H, Li C W P, Hung L.et al A standardized clinical series for work‐related lateral epicondylitis. J Occup Rehabil 200010143–152. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omer S R, Ozcan E, Karan A.et al Musculoskeletal system disorders in computer users: effectiveness of training and exercise programs. J Back Musculoskeletal Rehabil 2003179–13. [Google Scholar]

- 38.van den Heuvel S G, de Looze M P, Hildebrandt V H.et al Effects of software programs stimulating regular breaks and exercises on work‐related neck and upper‐limb disorders. Scand J Work Environ Health 200329106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bailey A, Starr L, Alderson M.et al A comparative evaluation of a fibromyalgia rehabilitation program. Arthritis Care Res 199912336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cedraschi C, Desmeules J, Rapiti E.et al Fibromyalgia: a randomised, controlled trial of a treatment programme based on self management. Ann Rheum Dis 200463290–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gowans S E, deHueck A, Voss S.et al A randomized, controlled trial of exercise and education for individuals with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res 199912120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mannerkorpi K, Nyberg B, Ahlmen M.et al Pool exercise combined with an education program for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. A prospective, randomized study. J Rheumatol 2000272473–2481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Redondo J R, Justo C M, Moraleda F V.et al Long‐term efficacy of therapy in patients with fibromyalgia: a physical exercise‐based program and a cognitive‐behavioral approach. Arthritis Rheum 200451184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faucett J, Garry M, Nadler D.et al A test of two training interventions to prevent work‐related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremity. Appl Ergon 200233337–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bohr P C. Office ergonomics education: a comparison of traditional and participatory methods. Work 200219185–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oliver K, Cronan T A, Walen H R.et al Effects of social support and education on health care costs for patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2001282711–2719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness. CRD guidelines for those carrying out or commissioning reviews. York: University of York, 1996

- 48.Lincoln A E, Vernick J S, Ogaitis S.et al Interventions for the primary prevention of work‐related carpal tunnel syndrome. Am J Prev Med 200018(Suppl 4)37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zwerling C, Daltroy L H, Fine L J.et al Design and conduct of occupational injury intervention studies: a review of evaluation strategies. Am J Ind Med 199732164–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]