Abstract

Background

Previous studies on worksite drinking norms showed individually perceived norms were associated with drinking behaviours.

Objective

To examine whether restrictive drinking social norms shared by workgroup membership are associated with decreased heavy drinking, frequent drinking and drinking at work at the worker level.

Methods

The sample included 5338 workers with complete data nested in 137 supervisory workgroups from 16 American worksites. Multilevel models were fitted to examine the association between workgroup drinking norms and heavy drinking, frequent drinking and drinking at work.

Results

Multivariate adjusted models showed participants working in workgroups in the most discouraging drinking norms quartile were 45% less likely to be heavy drinkers, 54% less likely to be frequent drinkers and 69% less likely to drink at work than their counterparts in the most encouraging quartile.

Conclusions

Strong associations between workgroup level restrictive drinking social norms and drinking outcomes suggest public health efforts at reducing drinking and alcohol‐related injuries, illnesses and diseases should target social interventions at worksites.

Keywords: alcohol, drinking, social norms, worksite, multilevel

Alcohol‐related diseases represent 4% of the global health burden.1 In the United States the economic costs of alcohol abuse were over 184.6 billion dollars in 1998, a 25% increase from 1992.2 Concerns over the role of workplaces as alcohol stimulating environments led to the 1988 Drug‐free Workplace Act reinforcing the importance of employee assistance programmes in managing substance abuse. Although these programmes may be effective for secondary prevention, they are limited for primary prevention.3,4 Additionally, workplace factors such as psychosocial conditions and normative contexts have been proposed as primary prevention targets.3,4,5

Ames and Janes suggested that the workplace normative context is crucial for changing drinking behaviours and preventing abusive drinking.4 Drinking social norms shared by a group define standards of appropriate behaviour, creating social controls that regulate workplace alcohol availability and drinking behaviours. Cross‐sectional studies have reported associations between drinking social norms and drinking.6,7,8 These studies, however, included a limited number of worksites (ranging from 1–3) and analysed individually perceived norms rather than the normative worksite context. To evaluate the influence of normative contexts over an individual's behaviour requires locating people within their reference groups so that simultaneous assessment of group and individual‐level influences can be made. Multilevel analysis is one approach for examining group norm influences on human behaviour and has been widely used in organisational research. Multilevel analysis disentangles sources of variability from different levels of a hierarchically nested structure, such as workers within workgroups.9

The multilevel approach has been echoed by the Institute of Medicine10 and highlighted in the recent STEPS conference aimed at the integration of worksite health promotion programmes with worksite health protection programmes.11 Both recognise that to change behaviour and improve health requires not only a focus on the individual but also on the social environment. Surprisingly, social norms are not discussed and instead norms continue to be approached from the individual (perceived) level in the application of health promotion theories like the sociocognitive theory and the theory of reasoned action.12 As Sorensen et al have stated, research that conceptualises and analyses social norms at a social level hopefully moves public health towards socially based interventions.13

The Work and Alcohol Study was conducted to evaluate the impact of normative worksite contexts on drinking behaviours. Groups of workers reporting to the same supervisor were surveyed on drinking and drinking norms while preserving their nesting within the organisation. Three different drinking behaviours were defined to evaluate the associations with drinking social norms: heavy drinking, frequent drinking and drinking at work. We proposed the hypothesis that restrictive drinking social norms shared by workgroups will be associated with decreases in heavy drinking, frequent drinking and drinking at work at the individual level, after controlling for a range of known covariates.

Methods

Sample

The present work is part of the Worksite Alcohol Study phase II (WAS‐II) conducted in 1994. Sampling procedures have been described elsewhere.14,15 Briefly, a random sample of 16 worksites from six Fortune 500 companies was selected from 114 worksites participant in the WAS‐I. Worksites were selected without replacement to represent equally six strata created by cross‐classifying information obtained from structured interviews with managers on worksite dominant occupations (ie, professionals, service and manufacturing) and worksite management drinking tolerance (ie, liberal/conservative). Measures of worksite management tolerance were based on responses of managers to questions about how tolerant the worksite was about drinking in an earlier survey of the same worksites.16 Supervisory workgroups were established in conjunction with management, identifying groups of workers reporting to the same supervisor in the organisational charts, under the premise that they should represent well‐contained production processes. At smaller worksites (n⩽800), all supervisory workgroups and workers were asked to participate. At larger worksites, supervisory workgroups were randomly selected, and workers within workgroups were asked to participate, to cover a quota of 500 workers from each worksite. Workers' link to supervisory workgroups was preserved. Surveys were mailed to worker homes; 6537 workers linked to 155 supervisory workgroups responded to the survey (71% response rate).

The final analytic sample included 5338 workers and 137 supervisory workgroups after excluding workers with missing data. Comparison of the full sample with the analytic sample showed no differences (table available from corresponding author).

Drinking behaviours

Three distinct drinking behaviours were defined for the analysis. Frequent drinking and heavy drinking were chosen to depict how often and how much a person drinks, following similar categorisations used in other alcohol studies.17,18 Additionally, a third variable indicating whether drinking behaviour occurred in work‐related situations was also measured. Frequency and amount of drinking were measured as ordinal measures, and following other work and drinking researched, collapsed for the analyses into dichotomous indicators of frequent and heavy drinking behaviours. Workers were classified as frequent drinkers if during the past 30 days they had drunk any beer, wine or liquor on 5 or more days in a week. Heavy drinking was defined according to Wechsler and colleagues.19 Men were considered heavy drinkers if they had drunk five or more drinks in one day in the past month, whereas for women the cut‐off point was four or more drinks. Drinking at work was an endorsement of different ways of drinking while at work that was collapsed into a dichotomous indicator. Workers were considered to drink at work if they reported drinking during the workday or if they had drunk alcohol in the past 30 days 2 hours before going to work, during lunch or work break, while working, before driving a vehicle on company business or at a company‐sponsored event. All three drinking measures have been found to be valid and reliable.20,21

Preliminary analyses indicated that each measure of drinking behaviour provided unique information; cross‐classification of the three drinking behaviour showed that only 70 (1.3%) workers had all three behaviours and, overall, between 20% and 30% of the workers had more than one drinking behaviour. Among frequent drinkers, however, 52% were also heavy drinkers, and 41% of those who drank at work were also heavy drinkers. Thus, despite some inter‐relationship, the three drinking measures captured different types of behaviours.

Drinking social norms

The drinking norms scale was originally developed by the research group based on the work of Ajzen and Fishbein22 and the review of the social norms literature. The scale collects information on two components of norms about drinking, one general and another work‐specific. Psychometric analyses indicated these two components constituted a single dimension, named “drinking social norms”. Drinking norms were measured with eight statements: (a) having a drink or two at home after work is a harmless way to relax and unwind; (b) getting together for drinks once in a while after work with coworkers can improve employees' morale; (c) drinking with clients or customers is good for business; (d) supervisors miss key information if they don't socialise with colleagues over a drink; (e) a drink or two a day is good for a person's health; (f) a few beers or drinks at lunch are a reasonable way to deal with a boring or repetitive job; (g) the more frequently people are exposed to alcohol, the more likely they are to develop a drinking problem; and (h) serving alcohol at company social events sets a bad example for employees. Workers reported their agreement from one to four points (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree). All items were rescored so high scores meant drinking was more undesirable or inappropriate. For each participant, the mean score of all eight items was computed (α = 0.79). Individual scores varied from 1.25 to 4 (mean 2.9).

To evaluate the extent that the variability of individual‐level norms could be attributed to effects at the workgroup level, we estimated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Briefly, the ICC is the proportion of the total variance accounted for by the second level variance.9 A two‐level random intercept model with the individual‐level drinking norms variable set as the outcome was fitted and variance components for level one and two were estimated. Level one variance was 0.229 while level two was 0.024, providing an ICC of 0.095. Thus, 9.5% of the variability observed in the individual norms scale can be attributed to the group level, supporting the decision to analyse the data in a multilevel fashion.

To represent workgroup drinking social norms, an aggregate measure was created by averaging individual scores within supervisory workgroups. Workgroup social norms ranged from 2.58 to 3.36 (mean 2.92), larger values implying more discouraging norms towards drinking. The validity of an aggregate measure is based on the assumption that there is high within‐group agreement among the workers in a supervisory group. Homogeneity of agreement within groups was assessed using the rwg(J) index.23 This index is calculated by comparing an observed group variance with an expected random variance. It is independent of the between‐groups variance, so it is particularly useful when group means are restricted in their range. Rather than obtaining a single summary for the entire sample as with the ICC, the rwg(J) index provides an agreement measure for each group. All but one (rwg(J) = 0.64) workgroup had rwg(J) values above 0.70 (median 0.90), indicating strong homogeneity and supporting the validity of aggregating individual‐level data to the workgroup level.

A compositional effects test was conducted to evaluate the predictive power of the aggregate measure beyond what could be explained by its origin individual variable. Compositional effects are the residual association between the aggregate measure and the outcome once the individual‐level variable used to generate the aggregated measure has been taken into account.9,24 Compositional effects differ from contextual effects in that the former are observed upon aggregation of individual data to the group level (eg, the group average of individuals' drinking norms), while the latter represent information directly measured at the group level (eg, written workgroup drinking policies).25 The compositional effects test decomposes observed effects into individual (ie, perceived drinking norms) and workgroup level (ie, drinking social norms) effects. Logistic regression models for each outcome were fitted with the individual and the aggregated drinking social norms measures. Statistically significant compositional effects (workgroup effects) were observed for heavy drinking (p = 0.012), frequent drinking (p = 0.03) and drinking at work (p<0.001). For each outcome, the statistically significant differences between the individual and aggregated coefficients supported the statement that the aggregate measure had predictive power beyond the level that could be explained from the individual variable.

To examine the dose–response in the relationship between drinking social norms and drinking behaviours, the aggregated workgroup drinking social norms measure was divided into four groups based on the quartile distribution (cut‐off points were 2.77, 2.93 and 3.03). Thus, workgroups in the first quartile had the most encouraging drinking norms while those in the fourth quartile had the most discouraging.

Covariates

Covariates selected based on the literature26,27,28,29,30,31 included gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, frequency of attendance at religious services (ie, religiosity), marital status, living with children, family history of alcohol abuse, self‐rated health, smoking status, job category, job seniority, weekly working hours, ambient hazards level, working offsite, working shift, unionisation, salary, job insecurity, alcohol availability at work, psychological job demands, job control and number of workers (in increments of 10 workers) in each supervisory workgroup. Finally, alcohol availability at work captured the ease of bringing alcohol to work, having a drink of alcohol during a break and having a drink of alcohol while working.

A covariate was included in the final model if it: (a) was not highly correlated with another covariate (r⩽0.70); (b) was associated with a drinking outcome in unadjusted regression analysis (p<0.25); and (c) continued to be significantly associated with the drinking outcome (p⩽0.05) in a final multilevel logistic regression model which included all selected covariates. Non‐significant variables in the final multiple regression models were individually re‐entered to reassess statistical significance. Table 1 shows the covariates included in final models, and their categorisation.

Table 1 Distribution of sample characteristics (n = 5338).

| Characteristics | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |

| Gender (female) | 2059 (38.6) |

| Age (years) | |

| ⩽34 | 1451 (27.2) |

| 35–44 | 1769 (33.1) |

| 45–54 | 1534 (28.7) |

| ⩾55 | 584 (10.9) |

| Race | |

| White, non‐Hispanic | 4618 (86.5) |

| Hispanic | 184 (3.4) |

| African‐American | 371 (7.0) |

| Other | 165 (3.1) |

| Education | |

| ⩽High school | 1588 (29.7) |

| Technical school | 599 (11.2) |

| Some college | 983 (18.4) |

| Two year college degree | 466 (8.7) |

| Four year college degree | 1081 (20.3) |

| Graduate degree | 621 (11.6) |

| Religiosity | |

| Once or more a week | 1639 (30.7) |

| At least once a month | 1477 (27.7) |

| Less than twice a year | 2222 (41.6) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 733 (13.7) |

| Married | 3016 (56.5) |

| Separated | 741 (13.9) |

| Remarried | 848 (15.9) |

| Living with children (yes) | 2429 (45.5) |

| Health‐related | |

| Smoker | |

| Never | 2502 (46.9) |

| Ex‐smoker | 1647 (30.9) |

| Smoker | 1189 (22.3) |

| Occupational | |

| Working offsite (yes) | 1275 (23.9) |

| Annual salary ($) | |

| <20K | 400 (7.5) |

| 20–29K | 1335 (25.0) |

| 30–39K | 1203 (22.5) |

| 40–49K | 876 (16.4) |

| 50–59K | 718 (13.5) |

| >60K | 806 (15.1) |

| Availability of alcohol at work (low) | 2157 (40.4) |

| Drinking | |

| Heavy drinking (yes) | 1015 (19.0) |

| Frequent drinking (yes) | 423 (7.9) |

| Drinking at work (yes) | 577 (10.8) |

| Design effects | |

| Worksite dominant occupation | |

| Professional | 1379 (25.8) |

| Service | 1201 (22.5) |

| Manufacturing | 2758 (51.7) |

| Management drinking tolerance (liberal) | 2377 (44.5) |

Statistical analysis

To examine the association between norms and drinking, two‐level random intercept logistic regression models were specified:

Logit(πij) = β0 cons + β1 normsj + β2 covariatesij + β3 designj + uj

Here, πij denotes the probability that the ith worker (level 1) in the jth group (level 2) will exhibit the drinking behaviour being analysed. The group level random error term is uj The term “cons” is equal to 1 so that β0 represents the intercept for the model, “covariates” represents the vector of selected covariates and the “design” vector comprises the two variables (management drinking tolerance and worksite dominant occupation) used to construct the sampling strata. The “norms” term represents workgroup drinking social norms as quartiles, using the lowest quartile as the reference. An additional analysis was done treating workgroup norms as a continuous.

After the model was fitted to the data, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for unit increases were calculated. Given that level 1 residuals are not calculated in logistic regression multilevel models, the evaluation of fit for final models was conducted by assessment of level 2 residuals through examination of plots of normal scores compared with standardised residuals and normal scores histograms. A small departure from normality was observed in the residuals for frequent drinking, but it was not considered to affect adversely the analysis owing to the relatively large number of observations at level 2. All multilevel analyses were conducted using MLwiN 2.02, while covariate selection was completed using STATA 9.1.

Results

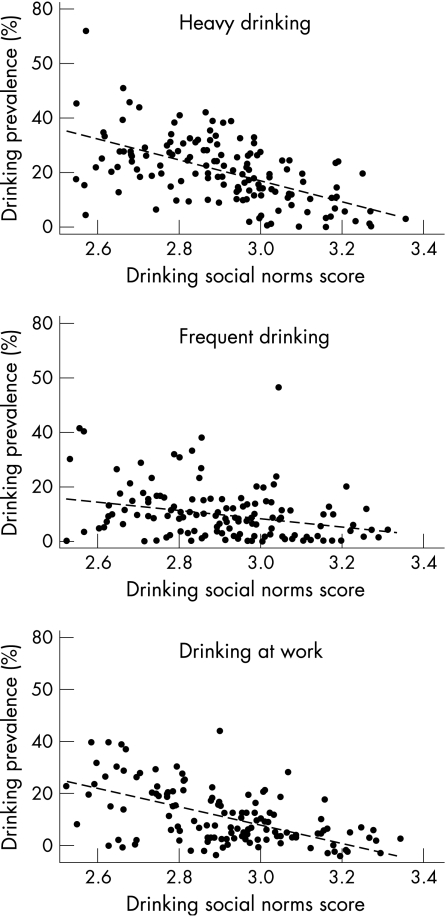

Table 1 shows sample characteristics. Nineteen per cent of the workers (n = 1015) were classified as heavy drinkers, 8% as frequent drinkers (n = 423), and 11% as drinking at work (n = 577). Supervisory workgroup size varied from two to 215 workers (median 26 workers). Figure 1 presents workgroup level scatter plots of the prevalence of drinking behaviours within the 137 workgroups against drinking social norms. The percentages of the various drinking behaviours decrease as social norms increase.

Figure 1 Scatter plot of the prevalence of drinking behaviours and drinking social norms among 137 workgroups.

Multilevel logistic analyses, adjusted for design variables (table 2), showed that discouraging drinking social norms were associated with a protective trend in the odds of heavy drinking, frequent drinking and drinking at work. Participants in the most discouraging quartile were 62% less likely to drink heavily, 64% less likely to drink frequently and 80% less likely to drink at work than their counterparts in the most encouraging quartile. Using workgroup drinking social norms as a continuous variable similar trends were observed, with reductions in heavy drinking (OR = 0.07, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.12), frequent drinking (OR = 0.05, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.11) and drinking at work (OR = 0.02, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.05).

Table 2 Bivariate associations between sample characteristics and heavy drinking, frequent drinking and drinking at work (n = 5338)*.

| Characteristics | Heavy drinking | Frequent drinking | Drinking at work | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR (95% CI) | p Value | % | OR (95% CI) | p Value | % | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Workgroup drinking social norms† | |||||||||

| 1st Quartile | 24.8 | 1 | 10.7 | 1 | 23.7 | 1 | |||

| 2nd Quartile | 23.9 | 0.84 (0.65 to 1.10) | 0.205 | 9.3 | 0.82 (0.55 to 1.22) | 0.327 | 12.4 | 0.57 (0.40 to 0.80) | 0.001 |

| 3rd Quartile | 18.7 | 0.58 (0.44 to 0.78) | <0.001 | 7.2 | 0.59 (0.39 to 0.92) | 0.018 | 7.3 | 0.45 (0.31 to 0.65) | <0.001 |

| 4th Quartile | 10.9 | 0.38 (0.27 to 0.54) | <0.001 | 5.4 | 0.36 (0.22 to 0.60) | <0.001 | 3.4 | 0.20 (0.12 to 0.34) | <0.001 |

| Sociodemographics | |||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 20.2 | 1 | 10.4 | 1 | 13.0 | 1 | |||

| Female | 17.1 | 0.55 (0.47 to 0.65) | <0.001 | 3.9 | 0.37 (0.28 to 0.48) | <0.001 | 7.3 | 0.47 (0.38 to 0.59) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| ⩽34 | 31.7 | 1 | 5.4 | 1 | 10.4 | 1 | |||

| 35–44 | 18.8 | 0.52 (0.44 to 0.62) | <0.001 | 8.5 | 1.47 (1.10 to 1.96) | 0.009 | 11.7 | 1.07 (0.85 to 1.36) | 0.549 |

| 45–54 | 11.9 | 0.32 (0.26 to 0.39) | <0.001 | 9.1 | 1.56 (1.16 to 2.11) | 0.003 | 11.2 | 1.16 (0.91 to 1.49) | 0.228 |

| ⩾55 | 6.7 | 0.17 (0.12 to 0.24) | <0.001 | 9.4 | 1.62 (1.12 to 2.36) | 0.011 | 8.2 | 0.94 (0.65 to 1.34) | 0.724 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White, non–Hispanic | 19.8 | 1 | 7.8 | 1 | 10.9 | 1 | |||

| Hispanic | 20.7 | 1.13 (0.78 to 1.64) | 0.508 | 7.6 | 0.97 (0.55 to 1.69) | 0.911 | 10.3 | 1.17 (0.71 to 1.92) | 0.539 |

| African‐American | 12.4 | 0.53 (0.38 to 0.74) | <0.001 | 10.2 | 1.44 (1.01 to 2.06) | 0.047 | 11.1 | 1.24 (0.87 to 1.75) | 0.236 |

| Other | 10.9 | 0.50 (0.30 to 0.82) | 0.006 | 6.1 | 0.74 (0.38 to 1.41) | 0.359 | 7.3 | 0.58 (0.32 to 1.08) | 0.085 |

| Education | |||||||||

| ⩽High school | 13.7 | 1 | 7.8 | 1 | 4.6 | 1 | |||

| Technical school | 18.5 | 1.49 (1.16 to 1.92) | 0.002 | 7.0 | 0.86 (0.60 to 1.24) | 0.414 | 6.5 | 1.38 (0.92 to 2.06) | 0.121 |

| Some college | 21.0 | 1.44 (1.16 to 1.79) | 0.001 | 7.2 | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.38) | 0.935 | 9.4 | 1.99 (1.44 to 2.76) | <0.001 |

| Two year college degree | 16.1 | 1.05 (0.78 to 1.40) | 0.748 | 4.7 | 0.63 (0.39 to 1.00) | 0.053 | 10.9 | 2.19 (1.49 to 3.21) | <0.001 |

| Four year college degree | 25.9 | 1.86 (1.51 to 2.29) | <0.001 | 8.8 | 1.21 (0.90 to 1.62) | 0.203 | 15.9 | 2.98 (2.21 to 4.03) | <0.001 |

| Graduate degree | 20.1 | 1.37 (1.06 to 1.78) | 0.018 | 11.1 | 1.39 (0.99 to 1.95) | 0.059 | 24.2 | 3.66 (2.65 to 5.06) | <0.001 |

| Religiosity | |||||||||

| Once or more a week | 10.6 | 1 | 4.6 | 1 | 8.1 | 1 | |||

| At least once a month | 19.4 | 1.97 (1.61 to 2.42) | <0.001 | 6.2 | 1.38 (1.01 to 1.90) | 0.042 | 11.4 | 1.38 (1.08 to 1.77) | 0.010 |

| Less than twice a year | 24.9 | 2.73 (2.26 to 3.28) | <0.001 | 11.5 | 2.78 (2.13 to 3.63) | <0.001 | 12.4 | 1.64 (1.31 to 2.06) | <0.001 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Never married | 35.5 | 1 | 5.7 | 1 | 12.8 | 1 | |||

| Married | 15.1 | 0.36 (0.30 to 0.44) | <0.001 | 7.7 | 1.22 (0.87 to 1.73) | 0.250 | 10.6 | 0.82 (0.63 to 1.06) | 0.139 |

| Separated | 21.9 | 0.55 (0.44 to 0.70) | <0.001 | 7.6 | 1.31 (0.86 to 1.99) | 0.205 | 10.5 | 0.95 (0.68 to 1.32) | 0.752 |

| Remarried | 16.4 | 0.43 (0.33 to 0.55) | <0.001 | 11.1 | 1.85 (1.25 to 2.73) | 0.002 | 10.1 | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.31) | 0.727 |

| Living with children | |||||||||

| No | 21.8 | 1 | 8.1 | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 15.7 | 0.68 (0.59 to 0.78) | <0.001 | 7.7 | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.12) | 0.376 | 10.4 | 0.83 (0.69 to 0.99) | 0.039 |

| Health‐related | |||||||||

| Smoker | |||||||||

| Never | 16.1 | 1 | 5.4 | 1 | 10.1 | 1 | |||

| Ex‐smoker | 18.8 | 1.29 (1.10 to 1.53) | 0.002 | 9.0 | 1.72 (1.35 to 2.20) | <0.001 | 12.3 | 1.40 (1.14 to 1.72) | 0.001 |

| Smoker | 25.6 | 1.95 (1.64 to 2.31) | <0.001 | 11.8 | 2.50 (1.94 to 3.22) | <0.001 | 10.3 | 1.39 (1.09 to 1.76) | 0.007 |

| Occupational | |||||||||

| Working offsite | |||||||||

| No | 18.5 | 1 | 7.0 | 1 | 7.7 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 20.8 | 1.14 (0.97 to 1.35) | 0.118 | 10.9 | 1.49 (1.19 to 1.87) | 0.001 | 20.6 | 2.13 (1.76 to 2.59) | <0.001 |

| Annual salary ($) | |||||||||

| <20K | 20.8 | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 4.3 | 1 | |||

| 20–29K | 18.1 | 1.13 (0.84 to 1.51) | 0.413 | 3.7 | 1.15 (0.61 to 2.16) | 0.673 | 5.6 | 1.78 (1.02 to 3.10) | 0.041 |

| 30–39K | 17.5 | 1.31 (0.96 to 1.78) | 0.090 | 7.6 | 2.35 (1.26 to 4.38) | 0.007 | 8.2 | 2.44 (1.38 to 4.30) | 0.002 |

| 40–49K | 20.8 | 1.76 (1.27 to 2.44) | 0.001 | 9.5 | 2.94 (1.56 to 5.56) | 0.001 | 10.1 | 2.95 (1.65 to 5.28) | <0.001 |

| 50–59K | 20.8 | 1.67 (1.19 to 2.34) | 0.003 | 11.0 | 3.64 (1.91 to 6.92) | <0.001 | 13.2 | 3.81 (2.12 to 6.82) | <0.001 |

| >60K | 18.5 | 1.32 (0.94 to 1.85) | 0.112 | 13.4 | 4.51 (2.39 to 8.51) | <0.001 | 25.3 | 6.20 (3.52 to 10.92) | <0.001 |

| Availability of alcohol at work | |||||||||

| High | 17.2 | 1 | 7.9 | 1 | 11.3 | 1 | |||

| Low | 21.7 | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.91) | 0.001 | 8.0 | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.14) | 0.485 | 10.1 | 1.09 (0.90 to 1.31) | 0.365 |

| Workgroup size | |||||||||

| Number of people (increments of 10) | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.98) | <0.001 | |||

| Design effects | |||||||||

| Worksite dominant occupation‡ | |||||||||

| Professional | 21.3 | 1 | 9.6 | 1 | 22.1 | 1 | |||

| Service | 25.8 | 1.30 (1.08 to 1.56) | 0.005 | 4.7 | 0.46 (0.34 to 0.64) | <0.001 | 6.6 | 0.25 (0.20 to 0.33) | <0.001 |

| Manufacturing | 14.9 | 0.67 (0.57 to 0.80) | <0.001 | 8.5 | 0.91 (0.72 to 1.14) | 0.423 | 7.0 | 0.31 (0.25 to 0.37) | <0.001 |

| Management drinking tolerance‡ | |||||||||

| Liberal | 21.3 | 1 | 8.6 | 1 | 15.5 | 1 | |||

| Conservative | 17.2 | 0.85 (0.74 to 0.98) | 0.025 | 7.4 | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.01) | 0.064 | 7.0 | 0.49 (0.40 to 0.58) | <0.001 |

*All bivariate analyses were conducted including design variables (worksite dominant occupation and management drinking tolerance).

†Quartile ranges: 1st 2.58–2.77, 2nd 2.78–2.93, 3rd 2.94–3.03, 4th 3.04–3.36.

‡Worksite dominant occupation adjusting for management drinking tolerance and vice versa.

After multivariate adjustment (table 3), the protective trend for discouraging norms towards drinking remained. Workers in the fourth quartile were 45% less likely to be heavy drinkers, 54% less likely to be frequent drinkers and 69% less likely to drink at work than their counterparts in the first quartile. Models using workgroup drinking social norms as a continuous variable generated similar results with reduced odds for heavy drinking (OR = 0.16, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.33), frequent drinking (OR = 0.10, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.23) and drinking at work (OR = 0.06, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.14).

Table 3 Adjusted models between drinking social norms and heavy drinking, frequent drinking and drinking at work (n = 5338).

| Characteristics | Heavy drinking | Frequent drinking | Drinking at work | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Workgroup Drinking Social Norms* | ||||||

| 1st Quartile | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2nd Quartile | 0.97 (0.76 to 1.24) | 0.807 | 0.90 (0.62 to 1.29) | 0.561 | 0.69 (0.49 to 0.97) | 0.031 |

| 3rd Quartile | 0.71 (0.54 to 0.94) | 0.015 | 0.64 (0.43 to 0.95) | 0.026 | 0.54 (0.37 to 0.78) | 0.001 |

| 4th Quartile | 0.55 (0.39 to 0.78) | <0.001 | 0.46 (0.29 to 0.74) | 0.001 | 0.31 (0.19 to 0.50) | <0.001 |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.57 (0.47 to 0.69) | <0.001 | 0.48 (0.36 to 0.64) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.53 to 0.86) | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ⩽34 | 1 | |||||

| 35–44 | 0.48 (0.39 to 0.59) | <0.001 | ||||

| 45–54 | 0.25 (0.19 to 0.31) | <0.001 | ||||

| ⩾55 | 0.12 (0.08 to 0.18) | <0.001 | ||||

| Race | ||||||

| White, non–Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hispanic | 1.00 (0.67 to 1.50) | 0.988 | 0.95 (0.53 to 1.71) | 0.868 | 1.29 (0.76 to 2.17) | 0.349 |

| African–American | 0.53 (0.38 to 0.75) | <0.001 | 2.17 (1.48 to 3.19) | <0.001 | 1.89 (1.30 to 2.74) | 0.001 |

| Other | 0.41 (0.24 to 0.68) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.32 to 1.22) | 0.167 | 0.44 (0.23 to 0.83) | 0.011 |

| Education | ||||||

| ⩽High school | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Technical school | 1.44 (1.10 to 1.89) | 0.008 | 1.24 (0.82 to 1.88) | 0.315 | ||

| Some college | 1.24 (0.98 to 1.57) | 0.067 | 1.80 (1.29 to 2.52) | 0.001 | ||

| Two year college degree | 0.88 (0.64 to 1.21) | 0.427 | 1.93 (1.29 to 2.88) | 0.001 | ||

| Four year college degree | 1.33 (1.03 to 1.71) | 0.026 | 2.28 (1.63 to 3.21) | <0.001 | ||

| Graduate degree | 1.00 (0.72 to 1.37) | 0.980 | 2.42 (1.65 to 3.56) | <0.001 | ||

| Religiosity | ||||||

| Once or more a week | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| At least once a month | 1.67 (1.35 to 2.08) | <0.001 | 1.29 (0.94 to 1.78) | 0.118 | 1.40 (1.08 to 1.81) | 0.011 |

| Less than twice a year | 2.11 (1.73 to 2.58) | <0.001 | 2.47 (1.88 to 3.26) | <0.001 | 1.74 (1.37 to 2.21) | <0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Never married | 1 | |||||

| Married | 0.53 (0.42 to 0.67) | <0.001 | ||||

| Separated | 1.02 (0.77 to 1.34) | 0.892 | ||||

| Remarried | 0.66 (0.49 to 0.89) | 0.006 | ||||

| Living with children | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.76 (0.64 to 0.90) | 0.002 | 0.78 (0.64 to 0.94) | 0.011 | ||

| Health–related | ||||||

| Smoker | ||||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Ex‐smoker | 1.77 (1.47 to 2.13) | <0.001 | 1.60 (1.24 to 2.06) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.25 to 1.92) | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 2.36 (1.93 to 2.87) | <0.001 | 2.47 (1.26 to 4.88) | 0.009 | 1.78 (1.37 to 2.30) | <0.001 |

| Occupational | ||||||

| Working offsite | ||||||

| No | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 1.43 (1.14 to 1.80) | 0.002 | ||||

| Annual salary ($) | ||||||

| <20K | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 20–29K | 1.11 (0.81 to 1.54) | 0.513 | 0.98 (0.51 to 1.88) | 0.952 | 1.67 (0.98 to 2.82) | 0.057 |

| 30–39K | 1.18 (0.93 to 1.52) | 0.180 | 1.70 (0.88 to 3.28) | 0.112 | 1.88 (1.02 to 3.44) | 0.041 |

| 40–49K | 1.53 (1.16 to 2.02) | 0.003 | 2.07 (1.05 to 4.08) | 0.035 | 1.75 (0.93 to 3.30) | 0.082 |

| 50–59K | 1.71 (1.27 to 2.31) | <0.001 | 2.34 (1.17 to 4.65) | 0.016 | 1.95 (1.02 to 3.72) | 0.043 |

| >60K | 1.74 (1.24 to 2.43) | 0.001 | 3.23 (1.63 to 6.42) | 0.001 | 2.97 (1.56 to 5.67) | 0.001 |

| Availability of alcohol at work | ||||||

| High | 1 | |||||

| Low | 1.28 (1.10 to 1.49) | 0.001 | ||||

| Workgroup size | ||||||

| Number of people (increments of 10) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.99) | 0.002 | ||||

| Design effects | ||||||

| Worksite dominant occupation | ||||||

| Professional | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Service | 1.47 (1.12 to 1.92) | 0.005 | 1.02 (0.65 to 1.59) | 0.930 | 0.58 (0.38 to 0.87) | 0.008 |

| Manufacturing | 0.99 (0.76 to 1.28) | 0.928 | 1.11 (0.79 to 1.55) | 0.563 | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.89) | 0.008 |

| Management drinking tolerance | ||||||

| Liberal | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Conservative | 1.06 (0.87 to 1.28) | 0.520 | 1.20 (0.91 to 1.59) | 0.204 | 0.73 (0.55 to 0.97) | 0.032 |

| Variance terms 2nd level | ||||||

| Empty model† Ω (SE) | 0.138 (0.040) | 0.281 (0.080) | 0.325 (0.082) | |||

| Covariate model‡ Ω (SE) | 0.044 (0.026) | 0.132 (0.058) | 0.181 (0.062) | |||

| Final model§ Ω (SE) | 0.019 (0.021) | 0.087 (0.051) | 0.121 (0.052) | |||

*Quartile ranges: 1st 2.58–2.77, 2nd 2.78–2.93, 3rd 2.94–3.03, 4th 3.04–3.36.

†Intercept + design variables.

‡Intercept + design variables + covariates.

§Intercept + design variables + covariates + group social norms.

Covariates included in multivariate models behaved as expected (table 3). Women, workers frequently attending religious services and people cohabiting were less likely to drink. Also, younger workers and workers who smoked were more likely to drink. Different covariate patterns were observed for each outcome (table 3), providing additional evidence of the independence of the drinking behaviours—that is, each outcome captured a different type of behaviour.

Main messages

This study extends previous research by using a larger range of organisations with different dominant occupations and managerial attitudes towards drinking.

Worksite social context is assessed, rather than individually perceived norms.

Workgroup norms discouraging drinking reduce the likelihood of both non‐work‐ (ie, heavy and frequent drinking) and work‐related (ie, drinking at work) drinking behaviours.

Discussion

Workers belonging to a workgroup with discouraging drinking norms are less likely to drink heavily, frequently or at work after a wide range of potential covariates have been controlled. Notably, while the observed association is stronger for drinking at work, workgroup norms are also strongly associated with decreased odds for drinking behaviours outside the work environment, suggesting the potential long reach of worksite‐based public health campaigns.

This study supports and extends previous research observing associations between workgroup norms and drinking at work. Delaney7 and Ames6 observed associations between drinking norms and workplace drinking in American companies. In Taiwan, Yang et al observed a significant association between encouraging drinking subcultures and increased alcohol consumption.8

Policy implications

The workplace normative context is crucial for changing drinking behaviours and preventing abusive drinking.

Development of alcohol prevention interventions should target group‐based norms instead of individuals' beliefs.

Worksite based social interventions may have the potential to affect health behaviours outside the workplace.

To our knowledge, this is the first study using a multilevel design and analysis with group level social norms measures. To extend the generalisation of previous norms research,30 our study was conducted in a wide range of organisations with different dominant occupations and managerial attitudes towards drinking. Importantly, the level 2 sample of 137 workgroups was large. Our study significantly adds to earlier research6,7,8 restricted to a few worksites and workgroups without measures of norms at the workgroup level. Also, we included measures of two general (frequent and heavy drinking) and one work‐related (drinking at work) drinking behaviour. Contrary to previous research, the drinking social norms scale used in the present study was constructed towards a restrictive (ie, discouraging drinking) rather than unrestrictive (ie, encouraging drinking) direction, supporting a primary prevention model.

Some study limitations must be noted. First, the cross‐sectional design precludes the disentanglement of temporal relations between social norms and drinking. Self‐selection of drinkers to workplaces that encourage drinking might produce clusters of workers with similar drinking beliefs, which in a cross‐sectional design could be interpreted as drinking social norms. Our study shows, however, that workgroup drinking norms remain associated with drinking after controlling for alcohol availability at the workplace and managerial tolerance to alcohol, two main characteristics that drink‐seeking workers may consider when selecting a job.

Second, the time lag from survey implementation to data analysis might limit external validity. However, the major American workplace alcohol control policy, the 1988 Drug‐free Workplace Act, was implemented 6 years before the survey. Since then, no other major modifications to workplace drinking or social drinking regulations have occurred. Therefore, the findings are unlikely to be threatened.

Third, a common criticism of aggregated measures in multilevel analysis is that aggregated measures capture individual and not group characteristics.32 Raudenbush's compositional effects test suggests the presence of an aggregate level exposure (ie, workgroup norms) operating independently of the individual exposure (ie, perceived beliefs). Furthermore, the rwg(J) index supports homogeneity of norms within groups. Together, these findings increase our confidence that the observed effect is at the workgroup level.

Finally, the strong associations found might be attributed to model misspecification.33 To reduce the chance for model misspecification, final model estimates were adjusted for a wide range of known drinking risk factors, such as gender, age, education, salary, alcohol, family history and religious service attendance. An evaluation of workgroup drinking social norms as a categorical and continuous variable was conducted to ensure results were not due to exposure misclassification during the analysis. Both approaches gave similar results. Also, central constructs from other potential workplace pathways associated with drinking were included: workplace alcohol availability, drinking managerial tolerance, and potential sources of stress such as having more than one job, working on a hazardous environment, job insecurity, high job demands or low job control. Therefore, our findings are unlikely to be due to model misspecification.

Further prospective multilevel research is required to demonstrate a causal relationship between drinking social norms and drinking. Observational measures of workgroup drinking social norms should be developed to eliminate threats posed by self‐reported compositional measures. Whereas worksite preventive research has focused on health promotion at the individual level and occupational health research has focused on health protection activities, the current study suggests the importance of worksite‐based social interventions as broad‐based public health campaigns.

Human participants protection

The Harvard School of Public Health Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with support from the Alcohol Beverage Medical Research Foundation (Dr Amick), the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse (Drs Amick and Mangione) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Dr Mangione). Dr Barrientos‐Gutierrez and Dr Gimeno were supported by a Fogarty International Center Training Grant (3 D43 TW00644). We acknowledge the contributions made by other people who have participated in this research: Diana Chapman Walsh, Lois Biener, Gary Gregg, Marianne Lee, Jeff Hansen, Jonathan Howland, Lauren Komp, Nicole Bell and Karen Kuhlthau. We are grateful to Anne L Dybala, who assisted in editing the manuscript.

Abbreviations

ICC - intraclass correlation coefficient

OR - odds ratio

References

- 1.Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet 2005365519–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harwood H J, Fountain D, Fountain G. Economic cost of alcohol and drug abuse in the united states, 1992: a report. Addiction 199994631–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roman P M, Blum T C. The workplace and alcohol problem prevention. Alcohol Res Health 20022649–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ames G M, Janes C. A cultural approach to conceptualizing alcohol and the workplace. (cover story). Alcohol Health & Research World 199216112 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trice H M, Sonnenstuhl W J. On the construction of drinking norms in work organizations. J Stud Alcohol 199051201–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ames G M, Grube J W. Social control and workplace drinking norms: a comparison of two organizational cultures. J Stud Alcohol 200061203–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delaney W P, Ames G. Work team attitudes, drinking norms, and workplace drinking. J Drug Iss 199525275 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang M J, Yang M S, Kawachi I. Work experience and drinking behavior: alienation, occupational status, workplace drinking subculture and problem drinking. Public Health 2001115265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raudenbush S W, Bryk A S.Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. Vol 1. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2002

- 10.Kaplan G, Everson S, Lynch J. The contribution of social and behavioral research to an understanding of the distribution of disease: a multilevel approach. In: Smedley B, Syme L, eds. Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press 200037–80.

- 11.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Steps to a healthier US workforce 2004 symposium. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/worklife/steps/2004/whitepapers.html, accessed 4 April 2007

- 12.Glanz K, Rimer B K, Lewis F M.Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass, 2002

- 13.Sorensen G, Barbeau E, Hunt M K.et al Reducing social disparities in tobacco use: a social‐contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue‐collar workers. Am J Public Health 200494230–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mangione T W, Howland J, Amick B.et al Employee drinking practices and work performance. J Stud Alcohol 199960261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangione L L, Mangione T W. Workgroup context and the experience of abuse: an opportunity for prevention. Work 200116259–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell N S, Mangione T W, Howland J.et al Worksite barriers to the effective management of alcohol problems. J Occup Environ Med 1996381213–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weitzman E R, Folkman A, Folkman M P H.et al The relationship of alcohol outlet density to heavy and frequent drinking and drinking‐related problems among college students at eight universities. Health Place 200391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leino E V, Romelsjö A, Shoemaker C.et al Alcohol consumption and mortality. II. Studies of male populations. Addiction 199893205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wechsler H, Dowdall G W, Davenport A.et al A gender‐specific measure of binge drinking among college students. Am J Public Health 199585982–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stacy A W, Widaman K F, Hays R.et al Validity of self‐reports of alcohol and other drug use: a multitrait‐multimethod assessment. J Pers Soc Psychol 198549219–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams G D, Aitken S S, Malin H. Reliability of self‐reported alcohol consumption in a general population survey. J Stud Alcohol 198546223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ajzen I, Fishbein M.Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. NJ: Prentice‐Hall Englewood Cliffs, 1980

- 23.LeBreton J M, James L R, Lindell M K. Recent issues regarding rWG, r WG, rWG, and r WG(J). Organ Res Methods 20058128–138. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raudenbush S. “Centering predictos” in multilevel analysis: choices and consequences. Multilevel Modelling Newsletter 1989110–12. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diez‐Roux A. A glossary for multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 200256588–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okosun I S, Seale J P, Daniel J B.et al Poor health is associated with episodic heavy alcohol use: evidence from a national survey. Public Health 2005119509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frone M R. Prevalence and distribution of alcohol use and impairment in the workplace: a U.S. national survey. J Stud Alcohol 200667147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holman T B, Jensen L, Capell M.et al Predicting alcohol use among young adults. Addict Behav 19931841–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alati R, Najman J M, Kinner S A.et al Early predictors of adult drinking: a birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 20051621098–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macdonald S, Wells S, Wild T C. Occupational risk factors associated with alcohol and drug problems. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 199925351–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore A A, Gould R, Reuben D B.et al Longitudinal patterns and predictors of alcohol consumption in the united states. Am J Public Health 200595458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diez‐Roux A V. Multilevel analysis in public health research. Annu Rev Public Health 200021171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diez‐Roux A V. Bringing context back into epidemiology: Variables and fallacies in multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health 199888216–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]