Abstract

Background

Reliable, noninvasive approaches to the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are needed. We tested the hypothesis that chest computed tomography-determined extent of pulmonary fibrosis and/or main pulmonary artery diameter can be used to identify the presence of pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Methods

Cross-sectional study of 65 patients with advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with available right-heart catheterization and high-resolution chest computed tomography. An expert radiologist scored ground-glass opacity, lung fibrosis, and honeycombing in the computed tomography images on a scale of 0-4. These scores were also summed into a total profusion score. The main pulmonary artery was measured at its widest dimension on the supine full chest sequence. At this same level, the widest aorta diameter was measured.

Results

Chest computed tomography-determined fibrosis score, ground-glass opacity score, honeycombing score, total profusion score, diameter of the main pulmonary artery, and the ratio of the pulmonary artery to aorta diameter did not differ between those with and without pulmonary hypertension. There was no significant correlation between mean pulmonary artery pressure and any of the chest computed tomography-determined measures.

Conclusions

High-resolution chest computed tomography-determined extent of pulmonary fibrosis and/or main pulmonary artery diameter cannot be used to screen for pulmonary hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients.

Keywords: pressure, pulmonary artery; hypertension, pulmonary; pulmonary fibrosis; high-resolution chest computed tomography; diagnosis

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a specific form of chronic fibrosing interstitial pneumonia associated with the histological appearance of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) 1. Pulmonary hypertension (PH) commonly complicates advanced IPF and is associated with worse prognosis 2-6.

Right heart catheterization (RHC) is the “gold standard” test to diagnose PH in IPF. However, RHC is invasive, costly and associated with complications. Although echocardiography is the most commonly used test to screen for PH in patients with ILD, it is not a reliable screening test 5,7. Reliable, noninvasive approaches to the diagnosis of PH in IPF would improve patient safety and reduce cost.

Previous studies in patients with pulmonary vascular disease and diverse lung conditions suggested that chest computed tomography (CT)-determined pulmonary artery diameters can be used to predict PH 8-12. However, this has not been tested in a homogeneous sample of patients with well-characterized IPF. Mechanistically, the severity of lung fibrosis should correlate with the prevalence and degree of PH. However, the relationships between CT assessments of lung fibrosis and pulmonary artery pressure have not been studied in patients with IPF. Therefore, in this study, we examined whether the CT-determined extent and severity of pulmonary fibrosis and diameter of the main pulmonary artery could be used to diagnose PH in advanced IPF patients.

Methods and Materials

Study sample

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all patients with IPF who were seen at our institution between July 1999 and June 2006. During their initial visit, all patients prospectively provided written informed consent (approved by the UCLA IRB) to use their clinical and demographic information for research purposes. All patients met accepted diagnostic criteria for IPF and the majority (74%) had histopathologic evidence of usual interstitial pneumonia 1. Three hundred and twenty two patients with well-documented IPF were seen at the center during this period and were candidates for inclusion in this study. To be included in the study, participants had to have had a high-resolution chest computed tomography (HRCT) within one month of the RHC. RHC were performed as part of the lung transplant evaluation (74%) or for participation in a clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00352482). Sixty-five patients met this entry criterion. Twenty-seven of them had PH.

Measurements

RHC data included measurements of pulmonary arterial pressures with the patient at rest. We defined PH as resting MPAP of > 25 mm Hg 13.

After at least five minutes of rest, pulse oximetry (SpO2) was measured on room air. Standard methodology was used for obtaining pulmonary function tests (PFT) and six-minute walk distance (6MWD) 14-17.

High-resolution Chest Computed Tomography (HRCT) Scoring System

All HRCTs were performed in the prone position acquiring 1.0- or 1.5-mm-thick sections at 1-cm throughout the entire thorax and then in the supine position. Full volume CT scans reconstructed every 3mm were acquired at suspended inspiration. HRCTs were reconstructed with a sharp kernel (Siemens, B50) and field of view (FOV) of widest outer rib to outer rib dimension. All studies were scored by one expert thoracic radiologist (JG) blinded to the patient's clinical and hemodynamic information, using a Likert scale (0 = absent, 1 = 1-25%, 2 = 26-50%, 3 = 51-75% and 4 = 76-100%) for extent of parenchymal abnormality in three categories: ground-glass opacity, lung fibrosis, and honeycombing. These scores were also summed into a total CT profusion score. This scoring system is based on that reported by Kazerooni et al 18. The following radiographic definitions were employed: ground-glass opacity: hazy parenchymal opacity in the absence of reticular opacity or architectural distortion; lung fibrosis: reticular opacification, traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis; honeycombing: clustered air-filled cysts with dense walls. Each lung lobe was scored separately (upper: lung apex to aortic arch, middle: aortic arch to inferior pulmonary veins, and lower: inferior pulmonary veins to diaphragm) and the mean score over all five lobes was computed for each category of parenchymal abnormality: fibrosis (CT-fib), ground glass opacity (CT-alv), honeycombing (CT-hc) and total profusion (CT-tot = CT-fib + CT-alv + CT-hc). Lobe scores were also weighted by typical relative size (right upper lobe: 0.0935; right middle lobe: 0.0935; right lower lobe: 0.363; left upper lobe: 0.155; and left lower lobe: 0.297) and summed to create weighted scores for fibrosis (wCT-fib), ground-glass (wCT-alv), honeycombing (wCT-hc) and total profusion (wCT-tot). We also created a maximum fibrosis score (mCT-fib) based on the most affected lobe.

The main pulmonary artery diameter (MPAD) was measured at its widest dimension on the supine full chest sequence. At this same level, the widest aorta diameter (AD) was measured and the MPAD/AD ratio was calculated. MPAD was also normalized by body surface area (BSA, m2) which was calculated according to the following equation: BSA = 0.00718 × W0.425 × H0.725, where W is body weight (kg), and H is body height (cm) 19.

Statistical Analysis

We compared mean values of all putative predictors of PH in patients with and without PH, using the Student t test. We also examined the Pearson correlation coefficient between MPAP and each of the putative predictors of PH. We then regressed MPAP on CT-fib, wCT-alv, wCT-hc and MPAD/AD in a multivariable linear regression model. The CT-derived scores chosen for the model were the ones with the highest correlation with MPAP in each category (fibrosis, ground glass opacity, honeycombing, and PA size).

All tests were two-tailed, and p values of < 0.05 were required for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C., USA).

Power Calculations

Our study was designed to have 80% power to detect 0.75σ or larger differences in putative predictors between the PH and no PH groups (where σ is the common standard deviation in the 2 groups) and to detect correlations of 0.34 or larger between MPAP and putative predictors.

Results

The study sample (n=65) had more advanced pulmonary disease (with lower FVC, DLCO, and room air SpO2) than the rest of the cohort (n=257), but was representative of the cohort with respect to age, gender, and race (Table 1). Mean MPAP in the study sample was similar to the mean MPAP in the 56 patients with RHC data who were excluded from the study because their RHC was more than one month distant from their HRCT.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for major characteristics

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or %* | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study sample (n=65) | Excluded (n=257) | ||

| Age (years) | 66.7 (8.2) | 66.9 (9.6) | 0.886 |

| Males (%) | 60.0 | 63.4 | 0.610 |

| Race (%) | 0.663 | ||

| Caucasian | 78.5 | 76.1 | |

| Hispanic | 16.9 | 15.7 | |

| Other** | 4.6 | 8.2 | |

| FVC (L) | 2.0 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.9) | 0.0008 |

| FVC % predicted | 54.3 (16.7) | 64.5 (18.8) | 0.0002 |

| DLco (mL/mm Hg/min) | 7.5 (3.5) | 9.7 (4.3) | <0.0001 |

| DLco % predicted | 31.1 (13.4) | 42.1 (18.7) | <0.0001 |

| Room air SpO2 (%) | 90.8 (4.7) | 92.8 (4.9) | 0.007 |

| MPAP (mm Hg) | 26.1 (8.9) | 27.5 (10.8)§ | 0.44 |

Age and gender available in all 322 patients; race available in 320 of 322; forced vital capacity (FVC, absolute and % predicted) available in 304 of 322; diffusing capacity (DLco, absolute and % predicted) available in 293 of 322; Resting room air pulse oximetry (SpO2 %) available in 266 of 322; mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP) available in 121 of 322; SD = standard deviation.

These 56 patients had RHC data but were excluded because their RHC were not performed within one month of the HRCT.

Includes Asian and African-American.

Comparisons of Patients With and Without Pulmonary Hypertension

Patients with and without PH did not differ with respect to age, gender, race and BSA (Table 2). As expected, those with PH had significantly lower DLco, FVC/DLco, 6MWD and resting room air SpO2 and significantly higher MPAP than those without PH, but they did not perform significantly worse on FVC or DLco/VA and had similar CT-derived scores for extent and severity of parenchymal disease and CT-derived MPAD, MPAD/AD and MPAD/BSA. Similarly, CT scores weighted by relative lobar size and the maximum CT-derived fibrosis score over all lobes did not differ between those with or without PH.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics Based on the Presence or Absence of PH by RHC

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPAP ≤ 25 (n=38) | MPAP > 25 (n=27) | ||

| Age (years) | 65.8 (7.3) | 67.9 (9.1) | 0.31 |

| Males (%) | 60 | 40 | 1.00 |

| Race (%) | 1.00 | ||

| Caucasian | 79 | 78 | |

| Hispanic | 16 | 18 | |

| Other** | 5 | 4 | |

| BSA | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.3) | 0.60 |

| CT-fib | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.7) | 0.80 |

| mCT-fib | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.8) | 0.81 |

| wCT-fib | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.7) | 0.94 |

| CT-alv | 1.7 (0.9) | 1.9 (1.0) | 0.60 |

| wCT-alv | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.0) | 0.50 |

| CT-hc | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) | 0.80 |

| wCT-hc | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.70 |

| CT-tot | 5.2 (1.6) | 5.5 (1.6) | 0.31 |

| wCT-tot | 5.5 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.5) | 0.37 |

| AD (mm) | 32.0 (2.6) | 32.1 (2.4) | 0.71 |

| MPAD (mm) | 31.3 (3.7) | 33.1 (2.4) | 0.19 |

| MPAD/AD | 0.98 (0.1) | 1.03 (0.1) | 0.10 |

| MPAD/BSA | 16.8 (2.6) | 17.5 (2.7) | 0.40 |

| FVC (L) | 1.9 (0.6) | 2.0 (0.8) | 0.81 |

| FVC % predicted | 52.3 (14.4) | 57.1 (19.7) | 0.61 |

| DLco (mL/mm Hg/min) | 8.0 (3.4) | 6.5 (3.6) | 0.06 |

| DLco % predicted | 33.5 (13.9) | 27.0 (11.7) | 0.04 |

| FVC%/DLco% | 1.8 (0.8) | 2.5 (1.6) | 0.04 |

| DLco/VA % predicted | 59.4 | 48.8 | 0.10 |

| SpO2 (%) | 93.3 (2.9) | 87.4 (4.6) | <.0001 |

| 6MWD (m) | 229 (163) | 61 (30) | 0.04 |

| MPAP (mm Hg) | 20.5 (3.1) | 33.9 (8.6) | <.0001 |

AD = CT-measured ascending aorta diameter, BSA = body surface area, CT-fib = CT-determined fibrosis score, CT-alv = CT-determined ground-glass score, CT-hc = CT-determined honeycomb score, CT-tot = total profusion score (CT-fib + CT-alv + CT-hc), FVC = forced vital capacity, DLco = diffusing capacity, MPAD = CT-measured main pulmonary artery diameter, mCT-fib = maximum CT-derived fibrosis score over all lobes, MPAP = mean pulmonary artery pressure, SpO2 = resting room air pulse oximetry, wCT-fib = weighted CT-determined fibrosis score, wCT-alv = weighted CT-determined ground-glass score, wCT-hc = weighted CT-determined honeycomb score, wCT-tot = weighted total profusion score, VA = alveolar volume, 6MWD = six-minute walk distance while breathing room air.

Includes Asian and African-American. SD = standard deviation.

Correlation Between Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure and Putative PH Predictors

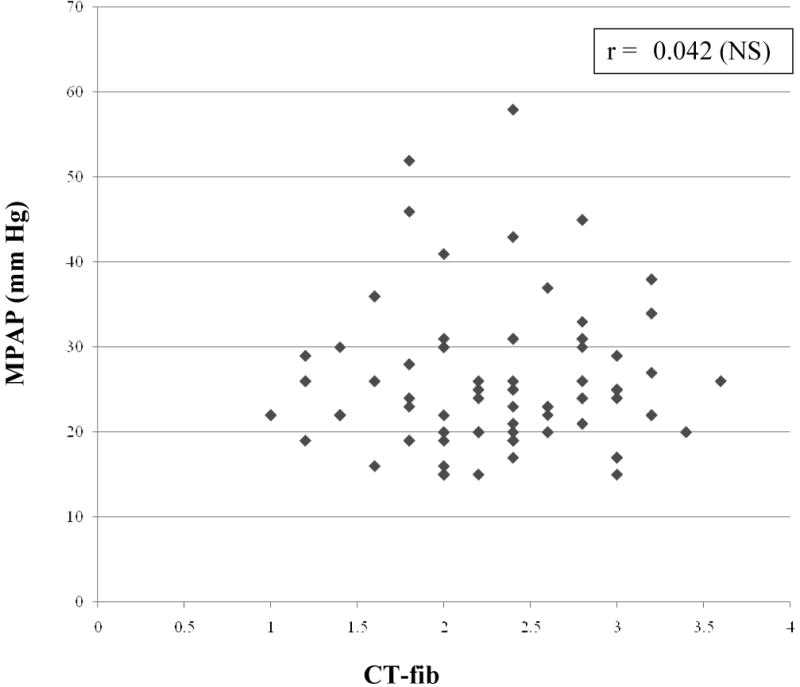

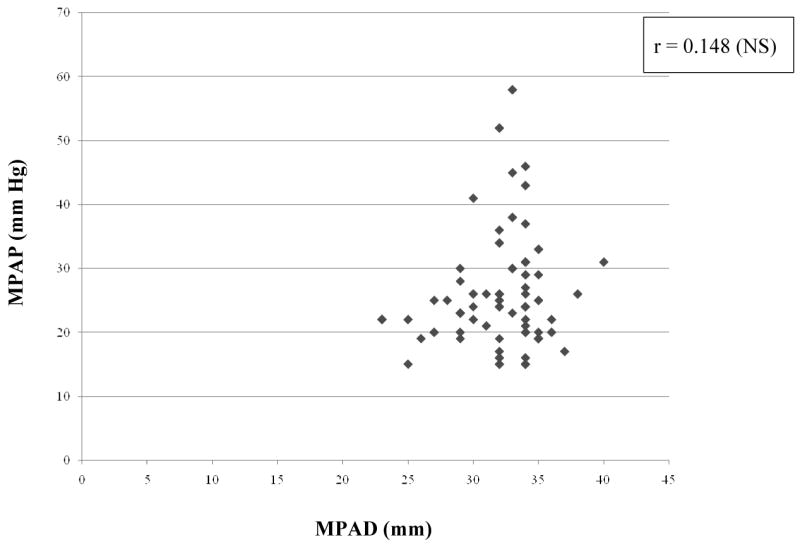

As shown in table 3, there were strong and statistically significant correlations in the expected directions between MPAP and both 6MWD and resting room air SpO2. We observed a modest and significant correlation between MPAP and DLco, DLco/VA% and FVC%/DLco%. However, there was no correlation between MPAP and FVC, CT-fib, CT-alv, CT-hc, CT-tot, MPAD, AD, MPAD/AD or the MPAD/BSA ratio (Figures 1 and 2). Similarly, there was no correlation between MPAP and CT scores weighted by relative lobar size or the CT-derived maximum fibrosis score. Furthermore, we found no correlation between other RHC-derived measurements (right atrial pressure, pulmonary vascular resistance, cardiac output, cardiac index) and any of the chest computed tomography-determined measures (data not shown).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients between the mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP) and putative predictors of pulmonary hypertension (PH)

| Variable | n | r | P-value** |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT-fib | 65 | 0.042 | 0.74 |

| wCT-fib | 65 | 0.022 | 0.86 |

| mCT-fib | 54 | 0.004 | 0.97 |

| CT-alv | 65 | 0.153 | 0.22 |

| wCT-alv | 65 | 0.171 | 0.17 |

| CT-hc | 65 | 0.009 | 0.94 |

| wCT-hc | 65 | 0.025 | 0.84 |

| CT-tot | 65 | 0.009 | 0.38 |

| wCT-tot | 65 | 0.119 | 0.34 |

| MPAD (mm) | 65 | 0.148 | 0.24 |

| MPAD/AD | 65 | 0.203 | 0.10 |

| MPAD/BSA | 63 | 0.136 | 0.29 |

| FVC (L) | 64 | 0.150 | 0.23 |

| FVC % predicted | 64 | 0.235 | 0.10 |

| DLco (mL/mm Hg/min) | 59 | -0.295 | 0.02 |

| DLco % predicted | 59 | -0.307 | 0.02 |

| DLco/VA % predicted | 52 | -0.408 | 0.003 |

| FVC%/DLco% | 59 | 0.435 | 0.0006 |

| SpO2 (%) | 59 | -0.527 | <0.0001 |

| 6MWD (m) | 17 | -0.569 | 0.002 |

AD = CT-measured ascending aorta diameter, BSA = body surface area, CT-fib = CT-determined fibrosis score, CT-alv = CT-determined ground-glass score, CT-hc = CT-determined honeycomb score, CT-tot = total profusion score (CT-fib + CT-alv + CT-hc), FVC = forced vital capacity, DLco = diffusing capacity, mCT-fib = maximum CT-derived fibrosis score over all lobes, MPAD = CT-measured main pulmonary artery diameter, MPAP = mean pulmonary artery pressure, SpO2 = resting room air pulse oximetry, wCT-fib = weighted CT-determined fibrosis score, wCT-alv = weighted CT-determined ground-glass score, wCT-hc = weighted CT-determined honeycomb score, wCT-tot = weighted CT-determined total profusion score, VA = alveolar volume, 6MWD = six-minute walk distance while breathing room air.

p value for test of zero correlation

Figure 1. Relationship between CT-determined fibrosis score (CT-fib) and measured mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP).

MPAP = mean pulmonary artery pressure, CT-fib = CT-determined fibrosis score

Figure 2. Relationship between CT-determined main pulmonary artery diameter (MPAD) and measured mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP).

MPAP = mean pulmonary artery pressure, MPAD = CT-determined main pulmonary artery diameter

Multivariable Linear Regression of MPAP on CT-derived Predictors

We regressed the MPAP on the CT scores (one from each category) with the highest correlation with MPAP (namely, CT-fib, wCT-alv, wCT-hc and MPAD/AD) in a multivariable linear regression model. The model adjusted R-square was 0.008 (p=0.35).

Discussion

Pulmonary hypertension is common in patients with advanced IPF and its presence has a significant adverse impact on survival 2,3. Noninvasive approaches to the diagnosis of PH in IPF are needed. In this study, we found that the CT-determined extent and severity of pulmonary fibrosis and main pulmonary artery diameter do not help in identifying PH in advanced IPF patients.

Intuitively, the severity of lung fibrosis should correlate with the prevalence and degree of PH. It seems logical that as the patient's IPF progresses and their lungs become more fibrotic, the cross-sectional area of the pulmonary vascular bed is reduced, the pulmonary vascular resistance rises, and pulmonary hypertension ensues; however, in this study, MPAP did not correlate with CT-based measurements of lung fibrosis and these variables did not differ between those with and without PH. Previously, we and others have shown that MPAP does not correlate with the degree of restrictive physiology (FVC, TLC) in IPF 2-5,20. PH is also disproportionate to the degree of restrictive ventilatory impairment (FVC) in patients with sarcoidosis and pulmonary Langerhan's cell histiocytosis 21,22. This study provides the first radiographic confirmation of the notion that the loss of pulmonary vascular conductance in IPF is not proportional to the extent of fibrosis. Vascular remodeling in IPF has been the subject of intense investigation over the last few years 23-27. There is evidence of regional heterogeneity with some areas demonstrating increased vascularity and other areas demonstrating decreased vascularity 23-27. While fibroblastic foci are notable for the absence of blood vessels, they are surrounded by a rich network of vessels 28. That is probably why there is little correlation between extent of fibrosis and MPAP. Although a higher extent of lung fibrosis on CT has been associated with worse outcome in IPF patients 29-31, our findings suggest that it is unlikely that a higher CT-fibrosis portends poor prognosis in connection with PH in IPF patients. By contrast, hypoxemia is an independent predictor of mortality in IPF 32-34 and it is also strongly linked to PH. This study and previous studies by us and others have consistently observed a strong association between high MPAP and low SpO2, suggesting that vasoconstriction in response to hypoxia is an important factor in the development of PH in IPF 2-5. Although initially reversible, the pathologic changes induced by hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction ultimately result in irreversible vascular remodeling 35,36

Previous studies of the association between pulmonary artery size and pulmonary artery pressure have been inconsistent, with some investigators finding correlations in the expected direction 9,11,37-39, and others reporting no correlation 40-42. Our results support the previous studies that have found no correlation between pulmonary arterial diameter and pulmonary artery pressure 40-42. It should be emphasized that our study population consisted of a homogeneous group of well-characterized IPF patients, whereas other investigators have focused on a wide spectrum of cardiopulmonary diseases 9,12,40,42, with a large proportion of patients with pulmonary vascular disease (PVD) such as idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolism 10,11,39,41,42. Although we cannot explain these disparate findings with certainty, it is quite possible that pulmonary artery size and pressure are correlated only in PVD and not in IPF. It is also possible that PH in our patients was not severe enough to cause increase in MPAD. In previous studies that have found associations between pulmonary artery size and PH, the PH cases were predominantly composed of patients with PVD with greater pulmonary artery pressures than our IPF patients with PH 8,11. Haimovici et al observed that when the severe PH cases were omitted by excluding patients with IPAH and patients with Eisenmenger's syndrome, the correlation between CT-measured pulmonary artery size and MPAP dropped 9. In a separate study, inclusion of PVD patients increased the MPAP of the PH group from 35.1 to 45.3 mm Hg. In that study, MPAD increased from 33 to 35 mm when PVD patients were included in the PH group 42, and the sensitivity and specificity of MPAD in predicting PH was lower in the subgroup of patients with parenchymal lung disease when compared to patients with PVD 42. Our study is consistent with these findings and together they suggest that PH due to IPF may not increase MPAD. It is also conceivable that the restrictive lung physiology in IPF may result in a traction effect on the mediastinal vascular structures, distending the pulmonary artery independent of the underlying pulmonary artery pressure; this effect may dampen the influence of the pulmonary artery pressure on the MPAD in patients with IPF. Ng et al showed in multivariable analysis that TLC, a marker of traction on mediastinal structures, independently contributed to MPAD 12. Consistent with this hypothesis, the pulmonary artery diameter in our control group (IPF patients without PH) was greater (31.3 ± 4 mm) than the values reported by others in their controls without cardiopulmonary disease (e.g., 24.2 ± 2 mm 11; 27.2 ± 3 mm 8).

Certain limitations of our study need to be acknowledged. This was a retrospective review of patients evaluated at a single center. Most of our patients underwent evaluation for lung transplantation, reflecting the presence of patients with more advanced IPF; hence, our results may not apply to the general population of IPF patients. However, we and others have shown that PH is more prevalent in patients with severe IPF (defined by reduced DLco and/or SpO2) 2-6; hence, this population is the one in whom identification of PH is more critical. Similar to other studies on this topic 37,39-41, CT scores were read by a single radiologist; however, since interobserver accuracy in measuring MPAD and extent of pulmonary fibrosis has been shown to be good 8,12,18, we do not believe that lack of additional readings by more than one expert radiologist biased our findings. Ours is a cross-sectional study of the association between CT-derived measures and PH in IPF patients. Hence, we cannot conclude that PH secondary to IPF is causally unrelated to changes in CT. That would require a longitudinal study. However, we can say that CT-derived measures of parenchymal disease and MPAD cannot be used to screen for PH in advanced IPF patients. Finally, our sample size may have limited our ability to find a real underlying association between CT-derived measures and PH. Since our study was powered to find correlations of 0.34 or larger, we can infer only that if there are undetected correlations between MPAP and one or more of the CT-derived measures, they are likely to be smaller than 0.34. Since this and previous studies 4,5 have found correlations between MPAP and simple measurements (such as 6MWD, SpO2, and PaO2) of the order of 0.5 and 0.7, we can conclude that HRCT-derived measures cannot distinguish between PH and no PH as well as simple clinical measurements such as oxygenation and the distance walked in six minutes.

In summary, HRCT-determined severity and extent of pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary artery size cannot be used to screen for PH in advanced IPF patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the NIH (5U10HL080411 and 5P50HL67665 to DAZ; HL080206 and HL086491 to JAB; AR055075 to MPK).

Abbreviations

- AD

CT-measured diameter of the ascending aorta

- BSA

body surface area

- CT-alv

CT-determined ground-glass score

- CT-fib

CT-determined fibrosis score

- CT-hc

CT-determined honeycomb score

- CT-tot

CT-determined total profusion score

- DLco

diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide

- FOV

field of view

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- ILD

interstitial lung disease

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- IRB

institutional review board

- mCT-fib

maximum CT-derived fibrosis score over all lobes

- MPAD

CT-measured main pulmonary artery diameter

- MPAP

mean pulmonary artery pressure

- PaO2

arterial blood oxygen tension

- PFT

pulmonary function tests

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- RHC

right-heart catheterization

- SpO2

resting room air pulse oximetry

- wCT-alv

weighted CT-determined ground-glass score

- wCT-fib

weighted CT-determined fibrosis score

- wCT-hc

weighted CT-determined honeycomb score

- wCT-tot

weighted CT-determined total profusion score

- VA

alveolar volume

- 6MWD

six-minute walk distance

Footnotes

All the work was performed at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Author Disclosure Information: David A. Zisman received research grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals and Cotherix Pharmaceuticals to do multi-center studies. Dr. Zisman is funded by the National Institutes of Health IPF Clinical Research Network, which includes participation in a pulmonary hypertension study with sildenafil.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:646–664. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.ats3-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lettieri CJ, Nathan SD, Barnett SD, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension in advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2006;129:746–752. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nadrous HF, Pellikka PA, Krowka MJ, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2005;128:2393–2399. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weitzenblum E, Ehrhart M, Rasaholinjanahary J, et al. Pulmonary hemodynamics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and other interstitial pulmonary diseases. Respiration. 1983;44:118–127. doi: 10.1159/000194537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zisman DA, Karlamangla AS, Belperio JA, et al. Prediction of Pulmonary Hypertension in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. ATS abstract 2007; 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamada K, Nagai S, Tanaka S, et al. Significance of pulmonary arterial pressure and diffusion capacity of the lung as prognosticator in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007;131:650–656. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arcasoy SM, Christie JD, Ferrari VA, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:735–740. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1130OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards PD, Bull RK, Coulden R. CT measurement of main pulmonary artery diameter. Br J Radiol. 1998;71:1018–1020. doi: 10.1259/bjr.71.850.10211060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haimovici JB, Trotman-Dickenson B, Halpern EF, et al. Relationship between pulmonary artery diameter at computed tomography and pulmonary artery pressures at right-sided heart catheterization. Massachusetts General Hospital Lung Transplantation Program. Acad Radiol. 1997;4:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(97)80111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinrich M, Uder M, Tscholl D, et al. CT scan findings in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: predictors of hemodynamic improvement after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Chest. 2005;127:1606–1613. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuriyama K, Gamsu G, Stern RG, et al. CT-determined pulmonary artery diameters in predicting pulmonary hypertension. Invest Radiol. 1984;19:16–22. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng CS, Wells AU, Padley SP. A CT sign of chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension: the ratio of main pulmonary artery to aortic diameter. J Thorac Imaging. 1999;14:270–278. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rich S, Dantzker DR, Ayres SM, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension. A national prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:216–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crapo RO, Morris AH, Gardner RM. Reference spirometric values using techniques and equipment that meet ATS recommendations. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123:659–664. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1981.123.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller A, Thornton JC, Warshaw R, et al. Single breath diffusing capacity in a representative sample of the population of Michigan, a large industrial state. Predicted values, lower limits of normal, and frequencies of abnormality by smoking history. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:270–277. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:720–735. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazerooni EA, Martinez FJ, Flint A, et al. Thin-section CT obtained at 10-mm increments versus limited three-level thin-section CT for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: correlation with pathologic scoring. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:977–983. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gannong W. Review of Medical Physiology. 17. London: Prentice Hall International; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nathan SD, Shlobin OA, Ahmad S, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary function testing in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007;131:657–663. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fartoukh M, Humbert M, Capron F, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension in histiocytosis X. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:216–223. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9807024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shorr AF, Helman DL, Davies DB, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in advanced sarcoidosis: epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:783–788. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00083404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keane MP, Arenberg DA, Lynch JP, 3rd, et al. The CXC chemokines, IL-8 and IP-10, regulate angiogenic activity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 1997;159:1437–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keane MP. Angiogenesis and pulmonary fibrosis: feast or famine? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:207–209. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2405007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cosgrove GP, Brown KK, Schiemann WP, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a role in aberrant angiogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:242–251. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1151OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebina M, Shimizukawa M, Shibata N, et al. Heterogeneous increase in CD34-positive alveolar capillaries in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1203–1208. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1111OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renzoni EA, Walsh DA, Salmon M, et al. Interstitial vascularity in fibrosing alveolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:438–443. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200202-135OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cool CD, Groshong SD, Rai PR, et al. Fibroblast foci are not discrete sites of lung injury or repair: the fibroblast reticulum. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:654–658. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-205OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gay SE, Kazerooni EA, Toews GB, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: predicting response to therapy and survival. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1063–1072. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9703022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zisman DA, Lynch JP, 3rd, Toews GB, et al. Cyclophosphamide in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a prospective study in patients who failed to respond to corticosteroids. Chest. 2000;117:1619–1626. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lynch DA, David Godwin J, Safrin S, et al. High-resolution computed tomography in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and prognosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:488–493. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1756OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hallstrand TS, Boitano LJ, Johnson WC, et al. The timed walk test as a measure of severity and survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:96–103. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00137203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lama VN, Flaherty KR, Toews GB, et al. Prognostic value of desaturation during a 6-minute walk test in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1084–1090. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200302-219OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timmer SJ, Karamzadeh AM, Yung GL, et al. Predicting survival of lung transplantation candidates with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: does PaO(2) predict survival? Chest. 2002;122:779–784. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.3.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tozzi CA, Poiani GJ, Harangozo AM, et al. Pressure-induced connective tissue synthesis in pulmonary artery segments is dependent on intact endothelium. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1005–1012. doi: 10.1172/JCI114221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vender RL. Chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Cell biology to pathophysiology. Chest. 1994;106:236–243. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.1.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bouchard A, Higgins C, Byrd BI, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in pulmonary arterial hypertension. American Journal of Cardiology. 1985;56:938–942. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90408-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frank H, Globits S, Glogar D, et al. Detection and quantification of pulmonary artery hypertension with MR imaging: results in 23 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:27–31. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.1.8517315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt H, Kauczor H, Schild H. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with chronic pulmonary thromboembolism: chest radiograph and CT evaluation before and after surgery. Euro Radiol. 1996;6:817–825. doi: 10.1007/BF00240678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore N, Scott J, Flower C, et al. The relationship between pulmonary artery pressure and pulmonary artery diameter in pulmonary hypertension. Clin Radiol. 1988;39:486–489. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(88)80205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murray T, Boxt L, Katz J, et al. Estimation of pulmonary artery pressure in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension by quantitative analysis of magnetic resonance images. J Thorac Imaging. 1994;9:198–204. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199422000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan RT, Kuzo R, Goodman LR, et al. Utility of CT scan evaluation for predicting pulmonary hypertension in patients with parenchymal lung disease. Medical College of Wisconsin Lung Transplant Group. Chest. 1998;113:1250–1256. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.5.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]