Summary

GRP94, an essential endoplasmic reticulum chaperone, is required for the conformational maturation of proteins destined for cell surface display or export. The extent to which GRP94 and its cytosolic paralog, Hsp90, share a common mechanism remains controversial. GRP94 has not been shown conclusively to hydrolyze ATP or bind co-chaperones, and both activities, by contrast, result in conformational changes and N-terminal dimerization in Hsp90 that are critical for its function. Here, we report the 2.4 Å crystal structure of mammalian GRP94 in complex with AMPPNP and ADP. The chaperone is conformationally insensitive to the identity of the bound nucleotide, adopting a “Twisted V” conformation that precludes N-terminal domain dimerization. We also present conclusive evidence that GRP94 possesses ATPase activity. Our observations provide a structural explanation for GRP94’s observed rate of ATP hydrolysis and suggest a model for the role of ATP binding and hydrolysis in the GRP94 chaperone cycle.

Introduction

GRP94, also known as gp96, is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) paralog of the hsp90 family. The hsp90 chaperones are a ubiquitous and highly conserved family of proteins required for the maturation of numerous cellular client polypeptides. The functions of these clients range from signal transduction to immune response (Pratt and Toft, 2003; Pearl and Prodromou, 2006), and inhibitors of hsp90s offer promise for novel therapies for cancers and other diseases (Chiosis, 2006; Sharp and Workman, 2006). GRP94 is implicated in the conformational maturation of proteins destined for cell surface display or export. Although numerous proteins have been linked to GRP94 in the cell, the list of confirmed GRP94 clients includes IgGs, some integrins, and all of the Toll-like receptors (Melnick et al., 1994; Randow and Seed, 2001; Yang et al., 2007), which suggests that GRP94 is required for the proper functioning of both the adaptive and innate immune systems. GRP94 knockout mouse embryos die in early gestation (Stoilova et al., 2000), and GRP94 is up-regulated in transformed cells, suggesting an expanded role for the chaperone beyond the maturation of immune response proteins. Therapies that target GRP94 may thus play a role in the treatment of diseases such as sepsis, heart disease, and cancer.

Hsp90 chaperones exist as obligate homodimers, with each protomer consisting of an N-terminal regulatory domain, a non-conserved and dispensible charged region, a middle domain, and a C-terminal dimerization domain. Hsp90s belongs to the GHKL family of proteins, whose members include DNA gyrase, Histidine kinase, and MutL. GHKL proteins are dimeric, bind ATP in their N-terminal domains using a “Bergerat fold”, and are ATPases (Dutta and Inouye, 2000). Tertiary and quaternary rearrangements serve to regulate ATP hydrolysis. By analogy to DNA gyrase and MutL, two well-studied GHKL family members (Wigley et al., 1991; Ban et al., 1999), it has been proposed that hsp90 chaperone activity is linked to an ATP-driven conformational change within the N-terminal domain, leading to the closure of a mobile “lid” over the ATP binding pocket. Lid closure allows transient N-terminal dimerization that aligns the catalytic residues from the N- and middle domains of the protein, and results in ATP hydrolysis. For cytosolic hsp90s, this process also involves the recruitment of several co-chaperone proteins, including p23, Aha1, and p50cdc37, that stabilize and regulate the activity of different conformational states. C-terminal dimerization is also required for efficient ATP hydrolysis in Hsp90 (Obermann et al., 1998; Chadli et al., 2000; Johnson et al., 2000; Wegele et al., 2003). Recent 3.5 Å and 3.4 Å crystal structures of yeast Hsp82 (Ali et al., 2006) and bacterial HtpG (Shiau et al., 2006) support the outlines of the proposed mechanism, and also revealed large conformational changes associated with adenosine nucleotide binding (Shiau et al., 2006).

Despite a high degree of sequence conservation among all hsp90 chaperones, many of the details of the cytoplasmic hsp90 mechanism are not recapitulated in, or remain undetermined, for GRP94. Notably, the question of whether GRP94 possesses a bona fide ATPase activity has been controversial (Li and Srivastava, 1993; Wearsch and Nicchitta, 1997; Nicchitta, 1998; Rosser and Nicchitta, 2000). A role for ATP hydrolysis in client protein maturation was suggested by experiments showing that Toll-like receptor surface expression was eliminated if the key ATP-binding (Asp149) or putative catalytic (Glu103) residues in GRP94 were mutated (Randow and Seed, 2001), but the same study also showed that some integrins were still produced by the putative catalytically defective mutant. Co-chaperones that might modulate GRP94 activity have not been identified, and GRP94 lacks the C-terminal MEEVD tetratricopeptide (TPR) motif. Finally, domains of Hsp90 do not functionally substitute in vivo for those of GRP94 (Randow and Seed, 2001). This suggests that, in addition to a possible mechanistic divergence, Hsp90 and GRP94 have evolved to specifically mature their own set of client proteins.

A key question in the study of the ER chaperone GRP94 is the role of adenosine nucleotides and the extent to which GRP94 mechanistically mimics cytoplasmic hsp90s and other members of the GHKL family. To address these issues, we have determined the experimentally phased structure of near full-length canine GRP94 in complex with the non-hydrolysable ATP analog, AMPPNP, at 2.40 Å resolution, and with ADP at 2.45 Å resolution. These structures are the first of any three-domain mammalian hsp90 and the first to be determined at high resolution. Surprisingly, these structures reveal that, despite the presence of the bound nucleotide, the chaperone adopts a catalytically silent conformation, which suggests that, contrary to models of hsp90 action, nucleotide binding does not drive the major conformational rearrangements in the chaperone. We also present kinetic data, however, that conclusively demonstrates that GRP94 possesses ATP hydrolysis activity, but exhibits a rate that is 5–25 fold slower than that of yeast Hsp82. These experiments have also revealed a regulatory role for the GRP94-specific pre-N terminal domain. Finally, guided by our structural data, we constructed a set of Hsp90/GRP94 chimeras that clearly show that the catalytic differences between Hsp90 and GRP94 lie entirely with their N-terminal domains. Together these observations provide a structural explanation for GRP94’s observed rate of ATP hydrolysis and suggest a new model for the role of ATP binding and hydrolysis in the GRP94 chaperone cycle.

Results

GRP94 adopts a previously unseen conformation for the hsp90 family

Four separate crystal structures of canine GRP94, which is 98.5% identical with human GRP94, were solved in the course of these experiments. Structures of GRP94 containing combinations of the N-terminal domain (N), middle domain (M), and C-terminal domain (C) were determined. The charged linker (residues 287–327), which forms an internal loop in GRP94 (Soldano et al., 2003) and is not conserved among the hsp90 family, was deleted in the NM and NMC constructs and replaced by four glycine residues. The signal sequence (residues 1–21) and the proteolytically sensitive pre-N terminal domain (residues 22–72) were also omitted in these constructs. The high resolution co-crystal structures of the near-full length GRP94-NMC (residues 73–754Δ287–327) in complex with AMPPNP and with ADP were solved using multiwavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) phases and refined to R/Rfree values of 0.243/0.289 and 0.248/0.299, respectively, against complete native data sets collected to 2.4 Å and 2.45 Å, respectively. Residues 73–84, 166–196, and 396–407 are disordered in these structures. The structure of unliganded GRP94-NM (residues 73–594Δ287–327) was solved by molecular replacement and refined to R/Rfree values of 0.314/0.332 against data collected to a resolution of 3.4 Å. The structure of GRP94-MC (residues 337–765) was solved using MAD phases to 4.0 Å and refined to R/Rfree values of 0.285/0.294 against native data to 3.2 Å. Data collection and refinement data are presented in Tables S1 and S2.

GRP94-NMC is arranged as a parallel homodimer (Figure 1A). Each protomer extends from its C-terminal dimerization domain with a moderate left-handed helical twist about the central axis of the dimer to form a “Twisted V” shape (Figure 1B). Because of the “Twisted V” shape of the GRP94 dimer, the two N domains, in both the ADP- or AMPPNP-bound complexes, do not engage their dimeric counterparts (Figure 1A, 1B). In fact, the two copies of helix N1, elements from each protomer that contribute to the N domain dimer interface of other GHKL family members (Ban et al., 1999; Ali et al., 2006), are over 70 Å apart and on opposite sides of the GRP94-NMC structure (Figure 1A). This conformation appears to be preferred for GRP94. Both copies of the two GRP94-NMC monomers that make up the crystallographic asymmetric unit adopt the same twisted shape. Furthermore, the structures of GRP94-NM and GRP94-MC, which crystallized in different space groups and under different conditions, and which together supply an additional 15 crystallographically independent views of the GRP94 polypeptide, recapitulate the inter-domain orientations seen in the full-length chaperone (Figure 1C, 1D).

Figure 1.

Overview of GRP94-NMC and comparison with GRP94-NM and GRP94-MC. The two protomers are shown in blue and cyan. A) Ribbon drawing of side and top views. The AMPPNP is shown as a stick model. In the top view, the positions of helix N1, which mediate N-domain dimer interactions, are indicated. B) Stereo surface view of the GRP94-NMC dimer. The N-domains do not contact each other. C) Comparison of GRP94-NMC, GRP94-NM, and GRP94-MC structures. Domain boundaries are indicated by dashed lines. The same relative orientation is shown for each structure. Only a single protomer from the GRP94-NMC and GRP94-MC dimers is shown. D) Overlay of the 3 structures. Colors are as in panel C.

Alignment of the 2.40 Å structure of GRP94-NMC with that of the 3.5 Å yeast Hsp82-NMC+SbaI/p23 structure (Ali et al., 2006) and the 3.4 Å HtpG-NMC structure (Shiau et al., 2006) reveals profound conformational differences among the 3 chaperones. Although the core elements of the individual domains of each chaperone overlap with each other well, with an average pair-wise RMSD of 1.03 Å for Cα atoms, the overall conformation of the 3 chaperones is very different (Figure 2). The yeast Hsp82-Sba1-AMPPNP ternary complex is in the “closed-dimer” conformation, which is characterized by the formation of a second dimer interface between the opposing N domains. Unliganded HtpG, on the other hand, adopts an “open dimer” conformation (Figure 2A) where the centers of the two N domains are over 100 Å apart and the two C-terminally dimerized protomers form an extended “V” shape. By contrast, GRP94 adopts a “Twisted V” shape. In this conformation, the GRP94 N domains are not dimerized and instead point in directions that are diametrically opposed to that required for dimerization. The GRP94 structure thus reveals a new conformation for the hsp90 family.

Figure 2.

Comparison of GRP94-NMC with yeast Hsp82 and HtpG. A) Ribbon diagrams of each structure. Hsp82 coordinates are from PDB code 2CG9, and HtpG coordinates are from PDB code 2IOQ. GRP94-NMC is AMPPNP-bound. Hsp82 is AMPPNP bound and co-chaperone Sba1 has been removed for clarity. HtpG is unliganded. B) Comparison of N- and M domain orientations in GRP94-NMC and Hsp82. GRP94 (blue) and Hsp82 (green) were superimposed using the middle and C-terminal domains for alignment. Alpha helices are shown as cylinders, and the AMPPNP is shown as sticks. The helix 4/5 lid of Hsp82 is colored pink. C) The N-middle interaction dictates the positioning of the catalytic residues. Views of the N-middle interaction in Hsp82 (green) and GRP94 (blue) with the N domains aligned. The catalytic E33 and R380 in Hsp82, and the equivalent E103 and R448 are indicated.

Particularly revealing from the comparison of these three hsp90 chaperone structures is the relative orientation of the N and M domains of each chaperone. This arrangement determines the alignment of the catalytic residues contributed from the two domains and is critically important for productive ATP hydrolysis. In AMPPNP-bound yeast Hsp82, the N and M domains are twisted like a “pepper mill” around the N-M domain junction so that the catalytic residues Glu33 and Arg380 are aligned. This conformation is stabilized by the N domain dimer, the bridging effect of the bound ATP, the use of a point mutant that destabilizes the open-lid conformation (Prodromou et al., 2000), and the bound co-chaperone SbaI. In contrast, the N and M domains of the AMPPNP-bound GRP94 are found in a relaxed conformation, where the N and M domains have rotated by almost 90 degrees relative to each other about the inter-domain junction (Figure 2B,C). This places the putative catalytic residue from the M domain, Arg448, over 21 Å away from the γ-phosphate of the bound nucleotide, a distance far too great to stabilize the leaving group for catalysis.

The relaxed N-M orientation seen in GRP94 is reminiscent of the N-M orientation first seen in the structures of un-liganded or ADP-bound HtpG-NM (Huai et al., 2005). Because the structure of AMPPNP-bound GRP94 exhibits no N-domain dimerization and adopts the relaxed N-M orientation that places Arg448 far away from the nucleotide phosphate, this conformation is likely to represent a catalytically incompetent state. This suggests that, unlike other members of the GHKL family, ATP binding alone does not drive GRP94 into a hydrolytically productive conformation.

GRP94 Domain Structures

The structure of the N domain of GRP94-NMC aligns well with that of the isolated N-domain solved previously (Soldano et al., 2003; Immormino et al., 2004; Dollins et al., 2005) (Figure 3). Nucleotide binding to GRP94-NMC is accompanied by a large (Δφ/Δψ of +144/−160 degree) rotation of the Gly198 hinge to accommodate the incoming nucleotide phosphates, the dissociation of strand N1 from the β-sheet core of the N-domain, and the rotational displacement of helix N1 by ~15 °. Contrary to the expected behavior of GHKL family members, however, and despite the presence of bound AMPPNP, the helix N4/N5 “lid” does not appear to be closed over the ATP binding pocket in the GRP94-NMC structure. While the lid is disordered beyond the first few residues, preventing direct observation of its position, insight into its position can be gained by comparing the trajectory of the GRP94-NMC lid termini (residues 163–165 and 197–199) to the termini of the corresponding lids in structures of the isolated GRP94 N domain, which were fully ordered. From this analysis, the positions of helix N1 and the lid termini in GRP94-NMC (Figure 3D, E) are consistent with the “extended-open” lid conformation (Figure 3B), and not with the “normal-open” (Figure 3A) or closed lid (Figure 3F) conformations seen in inhibitor-bound GRP94 or ATP-bound Hsp82, respectively. The “extended-open” conformation, whereby the lid is peeled back to fully expose the nucleotide binding pocket, is unique to GRP94 and was observed only in the adenosine nucleotide-bound complex (Immormino et al., 2004; Dollins et al., 2005). In addition, modeling the closed lid observed in the structure of yeast Hsp82-Sba1-AMPPNP onto the structure of GRP94-NMC results in a lid position that would deeply interpenetrate the GRP94 M domain. An Hsp82-like closed lid is thus sterically incompatible with the observed conformation of GRP94-NMC (Figure 3F). While significant rearrangements of the modeled Hsp82 lid can be proposed that would relieve the predicted clashes, the result would be a lid conformation for which there is as yet no evidence, and which in any case may not adequately cover the ATP binding pocket. Thus, the more likely interpretation of the structural data is that, despite the presence of bound AMPPNP, the GRP94 lid is not closed over the nucleotide binding pocket.

Figure 3.

GRP94 N domain conformations. A,B) Structures of the isolated N domain determined in the absence (A) or presence (B) of bound adenosine nucleotide. The core of the domain is colored gray, and the lid components, helices N1, N4, and N5, along with strand 1 are colored magenta or yellow. C) N domain as found in the AMPPNP-bound GRP94-NMC structure. The orientation of the molecule is the same as in panels A and B. The likely trajectory of the disordered portion of the helix N4/N5 lid is shown in dashed lines. D) Details of the backbones of the 3 N domains in the vicinity of the nucleotide binding pocket. Only the alpha carbons are shown. Colors are as in A, B, and C. The ball denotes the position of the Gly197 alpha carbon, and shows the backbone transition observed in the N domain when adenosine nucleotides bind. E) Close-up overlay as in D) showing the movement of helix N1 upon nucleotide binding. F) Superposition of yeast Hsp82-NMC (PDB code 2CG9) with GRP94-NMC. Hsp82 is in green, and GRP94 is in blue. The N domains from each structure were the basis for the alignment. The helix N4/N5 lid from Hsp82 is shown in pink. The molecular surface of the GRP94 M domain is shown.

The charged region at the end of strand N8 (residues 287–327) in the N domain is replaced in GRP94-NMC by 4 glycine residues. This region forms an internal loop that is anchored at each end by interactions between the anti-parallel β-strands N8 and N9 and is further stabilized by rare a “tryptophan zipper” motif (Cochran et al., 2001). Because of this arrangement, the charged region is not a flexible linker connecting the N- and M domains but instead is part of the N domain, as was predicted previously (Soldano et al., 2003).

In the C-terminal domain of GRP94, residues 755–765 form a sixth helix that significantly extends the dimer interface compared to Hsp82 and HtpG (Figure 4A). As seen in the GRP94-MC structure, helix C6 from each protomer contacts the loop region between helix C3 and strand C3 of the opposite protomer in the GRP94 dimer, effectively “strapping” together each chain of the C-terminal domain (Figure 4B), and extending the solvent excluded surface of the dimer interface from ~1220 Å2 without the straps to ~1825 Å2 with the straps. Like the N domain Trp zipper, this structured addition to the dimerization domain appears to be unique to GRP94. The C-terminus of prokaryotic chaperone HtpG lacks the “strap” residues, and in yeast Hsp82, the residues that might form the equivalent helix C6 are disordered (Ali et al., 2006). This disorder may reflect the fact that the C-terminus of cytoplasmic hsp90s must be free to interact with TPR-domain containing co-chaperones. GRP94 lacks a TPR region and likely does not interact with equivalent co-chaperones, and may require the extra C-terminal straps to impart more stability to the chaperone dimer.

Figure 4.

C-terminal domain of GRP94 has additional dimer interactions. A) The C-terminal domain. Helices comprising the strap residues are shown in gold. B) A potential client binding surface composed of Met-Met pairs and hydrophobic residues.

Along with the dimerization interface, the C domain of GRP94 also contains a potential protein binding surface that may be used for client or co-chaperone interactions. Alpha helix C2, which is not part of the four-helix dimerization bundle, projects out from the dimerization domain toward the empty space between the two protomers of the GRP94-NMC dimer. This helix contains a putative protein-protein binding interface (Figure 4C) composed of the central Met-Met pair (residues 658 and 662), four exposed aromatic residues (Tyr652, Trp654, Tyr677, and Tyr678) and one aromatic residue contributed from the M domain (Tyr574). The conserved Met-Met motif serves as a protein-protein interface in other systems (Headd et al., 2007) and was recently shown to mediate interactions between yeast Hsp82 and the glucocorticoid receptor (Fang et al., 2006).

Conformational changes in GRP94 occur in the transition from the apo- to the adenosine nucleotide bound state

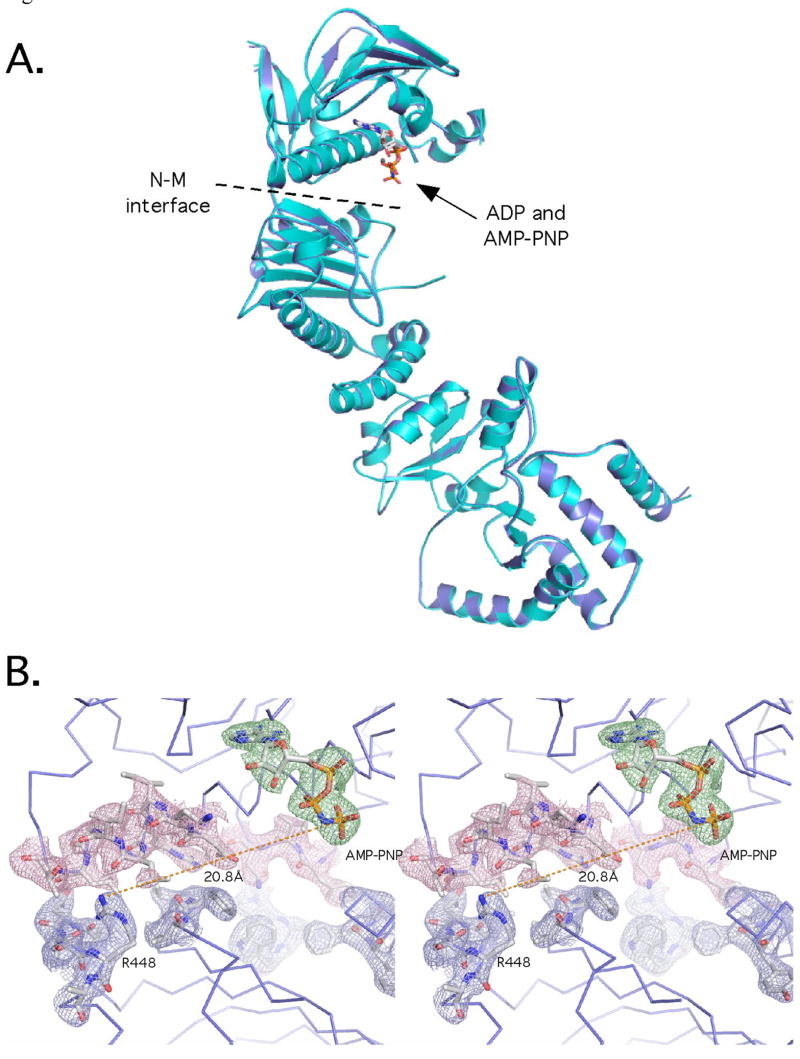

Models of hsp90 action and recent structural evidence suggest that hsp90 chaperones adopt dramatically different conformations depending on whether they are bound to ATP or ADP (Pearl and Prodromou, 2006; Shiau et al., 2006). If the conformational plasticity of bacterial and lower eukaryotic hsp90 chaperones is related to the chaperone cycle it is important to ask if these changes are common to GRP94 and the mammalian hsp90 homologs. To address this question we determined the co-crystal structures of GRP94-NMC bound to ADP and to the non-hydrolysable ATP analog, AMPPNP (Figure 5A). In both cases the chaperone-nucleotide complex was formed in solution prior to crystallization. As seen in Figure 5B, the high resolution of these structures allows for the clear identification of both nucleotides and the local environment in which they are bound. Remarkably, the identity of the bound nucleotide does not alter the conformation of GRP94-NMC. Indeed, both in overall conformation as well as in the details of their ligand binding pockets, the structures of the AMPPNP and ADP complexes are essentially identical. When combined with earlier structural studies of the isolated GRP94 N domain which showed that adenosine nucleotide binding altered the lid configuration (Immormino et al., 2004; Dollins et al., 2005), these observations suggest that ligand driven conformational changes in GRP94 are limited to the N domain and occur in the transition from the unliganded state to the adenosine nucleotide bound state, rather than from the ATP to the ADP state.

Figure 5.

ADP and AMPPNP-bound GRP94 have identical conformations. A) Overlay of the two nucleotide bound complexes. The AMPPNP complex is in blue, and the ADP complex is in cyan. Only one protomer of the GRP94 dimer is shown. B) Stereo view of the bound AMPPNP. SA omit electron density contoured at 1.3σ is shown with a 2 Å carve radius. The density for the nucleotide is shown in green, for the residues of the N domain in pink, and the M domain in blue. The position of Arg448 is indicated, and the distance to the gamma phosphate of the AMPPNP is shown with a dashed line.

The AMPPNP- and ADP-bound structures can explain why the nucleotide binding properties of GRP94 differ from that of other hsp90s. GRP94 binds ATP and ADP with Kd’s around 5 μM (Ge et al., 2006) and shows little discrimination between the two nucleotides. By contrast, other hsp90s bind ATP with Kd’s that are 10–100 fold weaker and, furthermore, exhibit a 5–10 fold higher affinity for ADP compared to ATP (Prodromou et al., 1997a; McLaughlin et al., 2004; Ge et al., 2006). These values can be explained by the observation here that the γ-phosphate of bound AMPPNP makes no direct or water mediated contacts to any portion of GRP94 (Figure 5B). Moreover, the remainder of the bound ligand makes no direct or water-mediated contacts with any elements outside of the GRP94 N domain, which can therefore contribute only marginally to the binding energy. In contrast, the β-phosphate of ADP bound to HtpG (Huai et al., 2005) and the γ-phosphate of AMPPNP bound to yeast Hsp82 (Ali et al., 2006) make direct hydrogen bonds with the M domains of those chaperones. These contacts are associated with large conformational changes in the protein and may incur significant entropic penalties that are reflected in the binding constants. Together these observations suggest that the ability of the bound adenosine nucleotide to drive GRP94 into alternate conformations differs significantly from the action of these nucleotides on HtpG and Hsp82.

GRP94 is an ATPase

While the central role of ATP hydrolysis in Hsp90 function is now established, the notion that GRP94 has a true ATPase activity has been controversial. Arguing for a role for ATP hydrolysis in GRP94 function is the fact that the putative catalytic residues (Glu103 and Arg448) are strictly conserved among all members of the hsp90 family. A weak ATPase activity has been reported in GRP94 purified from tissues (Li and Srivastava, 1993), but was not fully suppressed by repeated antibody depletion of the GRP94. Other groups subsequently failed to detect ATP hydrolysis above background (Wearsch and Nicchitta, 1997; Rosser and Nicchitta, 2000), leaving open the possibility that the weak hydrolysis detected initially might have arisen from one of the many contaminating enzymatic activities that co-purify with tissue-derived GRP94 (Wearsch and Nicchitta, 1997; Reed et al., 2002). Moreover, the misalignment of the putative catalytic residues in the GRP94-NMC structure described above supports the notion that GRP94 is not an ATPase. To address this issue, we tested purified, recombinant GRP94-NMC for ATPase activity.

The kinetic parameters of GRP94-NMC indicate that it has a significant ATPase activity, with a Kcat and Km of 0.02 ± 0.001 min−1 and 10 μM, respectively, at 37 °C (Figure 6). This rate of catalysis is only 20% of that of the yeast Hsp82 (Kcat 0.097±0.002, Km 47 μM), and is similar to rates reported for human Hsp90β in the absence of the co-chaperone AhaI or client protein (McLaughlin et al., 2002). The lower ATP Km for GRP94 means that the catalytic efficiency (Kcat/Km) of GRP94 is equal to that of yeast Hsp82 (2.0 × 10−3 min−1μM−1 vs. 2.1 × 10−3 min−1μM−1). We have established that this activity can only be ascribed to GRP94, since, as seen in Figure 6B, the GRP94 hydrolysis activity is completely abolished by the addition of the hsp90-specific inhibitor Radicicol. The presence or absence of the charged linker had no effect upon the kinetics of hydrolysis (not shown).

Figure 6.

GRP94 ATPase assays. Activity was monitored by the detection of free phosphate and represents the average of at least 3 independent measurements. A) GRP94 (white) and Hsp82 (shaded) constructs and chimeras used in these assays. S1 refers to strand N1, and H1 to helix N1. The GRP94 charged region segment is indicated by horizontal lines and that of Hsp82 by vertical lines. B,C,D) Specific activity of GRP94 and selected GRP94 mutants. Constructs used in each assay are indicated next to each reaction curve. E) Comparison of yeast Hsp82, GRP94-NMC, and Hsp82/GRP94 chimera ATPase rates. F) Summary of relative ATPase rates for GRP94 and Hsp82. Activity is given as a percentage of the Hsp82 rate.

The GRP94 ATPase activity requires the residues and domains that are essential for catalysis in cytoplasmic Hsp90. As seen in Figure 6D, when the conserved catalytic residues Glu103 from the N domain or Arg448 from the M domain were mutated to Alanines, hydrolysis was either abolished or reduced by more than 85%, respectively. GRP94 hydrolysis activity also depends on the dimerization of the C-terminal domain. As seen in Figure 6C, GRP94-NM (residues 73–594), which lacks the C-terminal dimerization domain, exhibits less than 15% of wild-type hydrolysis activity. Finally, consistent with a model where N dimerization is required, mutants of GRP94 lacking strand N1, or strand N1 and helix N1, were also defective in ATP hydrolysis (Figure 6C). Since all of these residues, secondary structural elements, and domains are required for ATP hydrolysis in cytoplasmic Hsp90, these results suggest that the mechanism of ATP hydrolysis in GRP94 follows that of the other GHKL proteins.

Structural studies have shown that the isolated N domain of GRP94 undergoes a conformational shift in response to nucleotide binding while the isolated N domain of Hsp82 does not (Immormino et al., 2004; Dollins et al., 2005). We thus asked whether the lower catalytic rate for GRP94, compared to yeast Hsp82, could be ascribed to differences in the two N domains. To address this, we expressed chimeric GRP94 molecules where the N domain of yeast Hsp82 (residues 1–273) was fused to the middle and C-terminal domains of GRP94 (residues 340–754; Hsp82N/GRP94-MC) or the N domain + partial M domain of yeast Hsp82 (residues 1–444) was fused to the complementary middle + C-terminal domains of GRP94 (residues 512–754; Hsp82NM1/GRP94-M2C). In the first chimera, HspN/GRP-MC, the catalytic Arg448 and the junction between the N and M domains are taken from GRP94. The second chimera contains those elements from Hsp82. As seen in Figure 6E, both Hsp82/GRP94 chimeras exhibit near wild-type Hsp82 rates of hydrolysis activity. Conversely, replacing the N domain of yeast Hsp82 with that of GRP94 reduced ATPase activity to only 30% of wild-type GRP94 activity. Together, these results show that the difference between the ATPase rates for GRP94 and cytoplasmic Hsp90 can be ascribed to the N domains of these chaperones.

In addition to a signal sequence (residues 1–21), that is cleaved upon entry into the ER, GRP94s from all species possess a ~50 amino acid pre-N terminal domain that is not found in the cytoplasmic hsp90 homologs. This domain, which encompasses residues 22–68 of canine and human GRP94s, contains a high proportion of charged amino acids and is proteolytically sensitive (D.E.D. and D.T.G., unpublished). In order to determine if this unique domain plays any other role in GRP94 function, we tested GRP94 molecules containing all or part of the pre-N domain (GRP94-pNMC) for ATPase activity. As seen in Figure 6B, both GRP94-pNMC constructs (22–754 287–327 and 28–754) exhibit severely reduced ATPase activity, with hydrolysis rates only 20% of the GRP94-NMC construct (73–754), and just 5% of that of yeast Hsp82. Although this domain is thought to play a role in ER calcium storage (Koch et al., 1986; Van et al., 1989), the addition of calcium (2–10 mM) did not result in increased hydrolysis (data not shown). The pre-N terminal domain of GRP94 thus appears to serve a regulatory role by suppressing ATP hydrolysis rates.

Discussion

The structures of GRP94 in complex with AMPPNP and ADP reported here represent the first picture of the full-length ER hsp90 paralog, the first structure of a mammalian hsp90, and the highest resolution structures of any member of the hsp90 family. GRP94 in complex with either AMPPNP or ADP adopts a previously unseen “Twisted V” conformation. This conformation precludes dimerization interactions between the two N domains of the chaperone, and also prevents the alignment of the residues from the N and M domains that are necessary for ATP hydrolysis. Despite this unexpected conformation in the crystal structure, we have shown that GRP94-NMC does indeed possess an intrinsic ATPase activity, with a catalytic efficiency of that is on par with that of yeast Hsp82, and greater than that reported for human Hsp90. Our kinetic results resolve a longstanding uncertainty regarding the extent to which GRP94 belongs mechanistically to the hsp90 and GHKL families. Equally important, the structural data indicate that binding of adenosine nucleotides alone is not sufficient to drive GRP94 into a conformation that is compatible with efficient ATP hydrolysis, and presumably, client maturation. Conformational changes recently proposed for HtpG and all hsp90s that rely on nucleotide identity (Shiau et al., 2006) may thus, in the case of GRP94, require the assistance of client proteins or other cellular factors.

Reconciling the structural observations with the enzymatic and evolutionary data suggests that GRP94 must undergo a series of significant structural reorganizations in order to effect ATP hydrolysis. In this model (Figure 7), which is supported by our data from structures of the isolated GRP94 N domain, the apo GRP94-NM structure, and the GRP94-NMC structures in complex with AMPPNP and ADP, ATP binding elicits conformational changes to the N domain of the protein as the helix N4/N5 lid and strand N1 are forced into the “extended-open” conformation, thereby priming the lid for either cross-protomer contacts or chaperone-client interactions. Rotations around the two N-M junctions then bring the faces of the N-domains containing helix N1 into opposition with one another. Dimerization interactions between the two N domains via swaps of strands N1 and helices N1 stabilize the relative orientation of the N- and M domains, thereby productively aligning the catalytic residues and the terminal phosphate of the nucleotide, leading to hydrolysis.

Figure 7.

Model of GRP94 ATP hydrolysis mechanism. The apo N domains of the “Twisted V” dimer (cartoon diagram in blue and cyan, helices represented as cylinders), undergo local conformational changes in the N mobile domain elements strand N1 and helix N1 (orange), and the Helix N4/N5 lid (green) upon binding nucleotide (shown as sticks). Each protomer of ATP bound “Twisted V” dimer, undergoes an ~90° rotation around the N/M interface aligning the nucleotide with the catalytic residues of the M domain and transiently dimerizing the N domains. The ATP bound “catalytically competent” closed dimer form is stabilized by cross-protomer interactions between strand N1 and helix N1 (orange) from the opposing chain, those elements previously rearranged upon nucleotide binding, as well a bridging effect between the terminal phosphate of the nucleotide and the catalytic residue of the M domain. The helix N4/N5 lid is closed over the nucleotide, trapping it in preparation for hydrolysis. After hydrolysis, there is a concomitant disassembly of the transient N dimer, rotation around the N/M interface, and re-structuring of the mobile domain elements of the N domain.

ATP hydrolysis is closely associated with the function of all members of the GHKL family, and current models of hsp90 action propose that ATP binding alone drives the chaperone into a hydrolytically productive conformation (Pearl and Prodromou, 2006). The results presented here suggest that, at least for GRP94, this is not the case. While ATP binding perturbs the GRP94 N domain, leading to the “extended-open” lid conformation, we suggest that the Twisted V, catalytically incompetent conformation of the chaperone likely represents the lower energy, ground state conformation, regardless of the nucleotide identity, and is thus much more frequently populated. Evidence supporting this proposition comes from the independently determined GRP94-NM and GRP94-MC structures, and the apo- and ADP-bound HtpG-NM structures (Huai et al., 2005), all of which exactly recapitulate the “relaxed” inter-domain arrangements seen in the full-length GRP94-NMC crystal structure. Further support for this proposal comes from the comparison of the catalytic rates of GRP94 and cytoplasmic yeast Hsp82. If the catalytic rate reflects, in part, the frequency with which the chaperone samples the hydrolytically productive “closed” conformation, then the lower rate observed for GRP94 suggests that GRP94 samples this conformation significantly less often than the yeast cytoplasmic paralog. Interestingly, human Hsp90β also exhibits unusually low intrinsic ATP hydrolysis rates (McLaughlin et al., 2002; Panaretou et al., 2002). By analogy to data presented here for GRP94, this raises the possibility that, unlike yeast Hsp82, mammalian Hsp90 homologs also adopt a variant of the catalytically incompetent ground state conformation and may not be driven efficiently into the closed conformation by ATP binding alone.

Differences in the N domains of GRP94 and Hsp82 account for the disparity in catalytic rates between the two paralogs, as shown by the kinetic analysis of the Hsp82/GRP94 chimeras we have constructed. In particular, for GRP94 to adopt a catalytically productive conformation, it must overcome at least two rate-limiting steps. These involve 1) escaping the Twisted V conformation by rotating about the N-M and M-C junctions, and 2) forming stable N domain dimers. In the structures of other GHKL members as well as that of yeast Hsp82, the N domain dimer is formed by cross-protomer interactions between opposing strands N1 and helices N1. Interestingly, these are precisely the elements that respond differently in GRP94 and Hsp82 when ATP binds to the two chaperones. Previously, we showed that strand N1, helix N1, and the lid of GRP94 move into an “extended-open” conformation upon ATP, ADP, or AMP binding (Immormino et al., 2004; Dollins et al., 2005). The isolated N domains of yeast Hsp82 or human Hsp90, in contrast, exhibit almost no conformational changes upon ATP binding (Prodromou et al., 1997a; Prodromou et al., 1997b). This suggests that, rather than representing an intermediate structure along the pathway to N domain dimerization, the “extended-open” conformation of the nucleotide-bound GRP94 N domain represents a primed state, which may serve as a platform for the binding of client proteins or other regulatory factors.

Although GRP94 and human Hsp90 exhibit differences in their catalytic rates compared to those reported for yeast Hsp82 or the prokaryotic HtpG, the fact remains that all of the observed rates of hydrolysis are remarkably slow compared to many other ATPases, with turnover times on the order of 10 minutes for Hsp82 and 45–250 minutes for GRP94. It would thus appear that while the catalytic machinery common to all GHKL proteins is present in GRP94 and Hsp90, it is remarkably inactive. Why might this be? One possibility is that the low intrinsic hydrolysis rate serves to limit ATP consumption within the highly abundant hsp90 chaperone population, which has been estimated to constitute up to 2% of the cellular polypeptide mass. Alternatively, the low intrinsic hydrolysis rate may indicate that further activation steps are required before hydrolysis and progression through the chaperone cycle can occur. For cytoplasmic hsp90s, confirmed activators include the co-chaperone Aha1, which has been shown to stimulate human and yeast Hsp90 ATPase rates by a factor of 100 or more (Panaretou et al., 2002). Similarly, at least one client protein of human Hsp90, the glucocorticoid receptor, has been shown to stimulate hydrolysis activity in this homolog (McLaughlin et al., 2002).

To date, co-chaperones for GRP94 have not been identified. Key co-chaperone binding regions, such as the TPR motif at the extreme C-terminal end of Hsp90, are absent in GRP94, and residues in Hsp90 that are implicated in binding the known cytoplasmic co-chaperones are not conserved between Hsp90 and GRP94. This suggests that ER-resident co-chaperones, if they exist, will not be simple homologs of their cytoplasmic cousins. Alternatively, extrapolating from the observation that some clients stimulate Hsp90 hydrolysis activity in vitro, and, given that the smaller client pool for GRP94 is likely to be structurally less diverse, it is conceivable that client proteins themselves may act as stimulatory co-chaperones for GRP94.

Cycles of ATP binding and hydrolysis are integral elements of the client protein maturation cycle, but considerably less is known about the conformational changes in hsp90s that are associated with client binding, maturation, and release. Given the overall diversity of the client pool for all hsp90s, it is possible that more than one surface of the chaperone is used to interact with different clients. Thus, while it has been proposed that clients interact in the cleft of the “open V” conformation in HtpG (Shiau et al., 2006), similar conformations for other hsp90s have not been observed, and a client protein has recently been shown to interact with a different surface of Hsp82 (Vaughan et al., 2006). For GRP94, the relatively compact, “Twisted V” conformation hides much of the surfaces that are exposed in the HtpG “open V”, suggesting that these are not significant client binding surfaces for the ER paralog. Similarly, extended and compact conformations of HtpG in complex with ADP have been observed crystallographically or by electron microscopy. While it is unclear why the HtpG conformation would differ so dramatically depending on the structure determination technique, it was proposed that these two forms represent different stages in the chaperone cycle. We have determined the structure of ADP-bound GRP94, and a direct comparison between HtpG-ADP and GRP94-ADP shows that the two conformations are dramatically different. While the data available prevents us from being able to reconcile these differences, we do note that the electron micrograph images of ADP-bound HtpG (Shiau et al., 2006) are also compatible with slightly foreshortened projections of the Twisted V GRP94 conformation. More data will be needed to reconcile these potential differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic hsp90 chaperone cycles.

In summary, we have shown conclusively that GRP94 possess an ATPase activity and that the structure of full length GRP94 reveals a new conformation for the hsp90 family that likely represents the principal conformation for the chaperone in the absence of client proteins or accessory factors. The structure explains the remarkably low rate of ATPase activity determined for GRP94, and may also reflect an intrinsic conformation of all hsp90s, which as a family exhibit dramatically lower ATP hydrolysis rates compared to other cellular chaperones and enzymes that hydrolyze ATP. This catalytically incompetent, yet ATP-bound conformation may explain how the large cohort of hsp90 chaperones in the cell is tolerated without becoming an energetic burden, and suggests that, like other cellular processes, substrates, co-factors, or accessory proteins are required for effective chaperone activation. The data presented here places GRP94 firmly within the hsp90 family, but highlights mechanistic differences that may distinguish mammalian hsp90s from their lower eukaryotic and bacterial homologs. Further work is now needed to explore how client proteins and accessory factors interact with these chaperones and contribute to their regulation.

Experimental Procedures

Protein Production and Crystallization

Constructs of canine GRP94 pET15b(73–594 287–327), GRP94 pET28b(337–765), and GRP94 pET15b(73–754 287–327) were expressed as His-tagged fusion proteins in E. coli. For those constructs containing the N domain, a charged region (287–327) was replaced by a four-glycine insertion. Proteins were purified by sequential passage over Nickle, anion exchange, and gel filtration columns. Crystals of GRP94-NMC and GRP94-MC were grown by hanging drop vapor diffusion. Crystals of GRP94-NM were grown using the microbatch method. Details of protein expression and purification and crystallization are presented in the Supplementary materials section.

Data collection and Structure Solution

Crystals were equilibrated into a cryo-protection solution before flash cooling in LN2. X-ray data was collected using tunable synchrotron radiation. The GRP94-MC and GRP94-NMC structures were solved with experimental MAD phases and improved by manual placement of homology model domains. The GRP94-NM structure was solved by molecular replacement using a starting model derived from the GRP94-NMC structure. Details of the data collection, structure solution and phasing are presented as Supplementary Materials.

ATP hydrolysis assay

ATP hydrolysis assays were performed using the PiPer Phosphate Assay kit (Invitrogen). Purified protein at 5 μM (GRP94 constructs) or 2.5 μM (Hsp82 and Hsp82/GRP94 chimeras) was incubated with 0–1600 μM ATP in the presence or absence of Radicicol (25μM) at 37°C for 90 or 120 min. Fluorescence was measured at 544 nm/590 nm (excitation/emission) on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax Gemini XS plate reader and corrected by the following equation: enzyme activity = full reaction (all components) - no enzyme control (either ATP or ATP+Rdc background) – no substrate control (enzyme only) + no enzyme/no substrate control (buffer background). Fluorescence was converted to free phosphate using a phosphate standard curve. Data were analyzed using the program Prism. Enzyme activities are averages of at least three independent measurements.

Supplementary Material

- Purification, Crystallization, Structure Solution, and ATPase assay methods

- Figure S1: Initial M.A.D. electron density maps for the GRP94-NMC-AMPPNP complex and the GRP94-MC structure.

- Figure S2: Representative electron density and crystallographic data quality for the GRP94-NMC-ADP/AMPPNP complexes.

- Figure S3: Representative electron density and crystallographic data quality for the apo GRP94-NM and GRP94-MC structures.

- Table S1: Data collection and refinement statistics, GRP94-NMC

- Table S2: Data collection and refinement statistics, GRP94-NM, GRP94-MC

- Table S3: Summary of Kinetic data

- Sequence alignments

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. R. Hegde, C. Nicchitta, and N. Que for critical reading of the manuscript, the Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute for high-throughput crystal screening, Dr. J. York for advice and the gracious use of lab space, and Dr. J. Buchner for inspiring the ATP hydrolysis experiments. X-ray diffraction data was collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL), beamline 11-1, the Advanced Light Source (ALS), beamline 8.2.1, and the Advanced Photon Source (APS), beamline 22-ID. This work was supported by the NIH grant CA095130 to D.T.G. and from a grant from the John R. Oishei Foundation of Buffalo.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali MM, Roe SM, Vaughan CK, Meyer P, Panaretou B, Piper PW, Prodromou C, Pearl LH. Crystal structure of an Hsp90-nucleotide-p23/Sba1 closed chaperone complex. Nature. 2006;440:1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/nature04716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban C, Junop M, Yang W. Transformation of MutL by ATP binding and hydrolysis: a switch in DNA mismatch repair. Cell. 1999;97:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadli A, Bouhouche I, Sullivan W, Stensgard B, McMahon N, Catelli MG, Toft DO. Dimerization and N-terminal domain proximity underlie the function of the molecular chaperone heat shock protein 90. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12524–12529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220430297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiosis G. Targeting chaperones in transformed systems--a focus on Hsp90 and cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2006;10:37–50. doi: 10.1517/14728222.10.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran AG, Skelton NJ, Starovasnik MA. Tryptophan zippers: stable, monomeric beta -hairpins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5578–5583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091100898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollins DE, Immormino RM, Gewirth DT. Structure of Unliganded GRP94, the Endoplasmic Reticulum Hsp90: Basis for Nucleotide-Induced Conformational Change. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30438–30447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503761200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta R, Inouye M. GHKL, an emergent ATPase/kinase superfamily. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:24–28. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Ricketson D, Getubig L, Darimont B. Unliganded and hormone-bound glucocorticoid receptors interact with distinct hydrophobic sites in the Hsp90 C-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18487–18492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609163103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge J, Normant E, Porter JR, Ali JA, Dembski MS, Gao Y, Georges AT, Grenier L, Pak RH, Patterson J, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of hydroquinone derivatives of 17-amino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin as potent, water-soluble inhibitors of Hsp90. J Med Chem. 2006;49:4606–4615. doi: 10.1021/jm0603116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headd JJ, Ban YE, Brown P, Edelsbrunner H, Vaidya M, Rudolph J. Protein-protein interfaces: properties, preferences, and projections. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2576–2586. doi: 10.1021/pr070018+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huai Q, Wang H, Liu Y, Kim HY, Toft D, Ke H. Structures of the N-terminal and middle domains of E. coli Hsp90 and conformation changes upon ADP binding. Structure. 2005;13:579–590. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immormino RM, Dollins DE, Shaffer PL, Soldano KL, Walker MA, Gewirth DT. Ligand-induced conformational shift in the N-terminal domain of GRP94, an Hsp90 chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46162–46171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BD, Chadli A, Felts SJ, Bouhouche I, Catelli MG, Toft DO. Hsp90 chaperone activity requires the full-length protein and interaction among its multiple domains. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32499–32507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G, Smith M, Macer D, Webster P, Mortara R. Endoplasmic reticulum contains a common, abundant calcium-binding glycoprotein, endoplasmin. J Cell Sci. 1986;86:217–232. doi: 10.1242/jcs.86.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Srivastava PK. Tumor rejection antigen gp96/grp94 is an ATPase: implications for protein folding and antigen presentation. Embo J. 1993;12:3143–3151. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin SH, Smith HW, Jackson SE. Stimulation of the weak ATPase activity of human hsp90 by a client protein. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:787–798. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin SH, Ventouras LA, Lobbezoo B, Jackson SE. Independent ATPase activity of Hsp90 subunits creates a flexible assembly platform. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:813–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick J, Dul JL, Argon Y. Sequential interaction of the chaperones BiP and GRP94 with immunoglobulin chains in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature. 1994;370:373–375. doi: 10.1038/370373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicchitta CV. Biochemical, cell biological and immunological issues surrounding the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone GRP94/gp96. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermann WM, Sondermann H, Russo AA, Pavletich NP, Hartl FU. In vivo function of Hsp90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:901–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaretou B, Siligardi G, Meyer P, Maloney A, Sullivan JK, Singh S, Millson SH, Clarke PA, Naaby-Hansen S, Stein R, et al. Activation of the ATPase activity of hsp90 by the stress-regulated cochaperone aha1. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1307–1318. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00785-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl LH, Prodromou C. Structure and mechanism of the hsp90 molecular chaperone machinery. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:271–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt WB, Toft DO. Regulation of signaling protein function and trafficking by the hsp90/hsp70-based chaperone machinery. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:111–133. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C, Panaretou B, Chohan S, Siligardi G, O’Brien R, Ladbury JE, Roe SM, Piper PW, Pearl LH. The ATPase cycle of Hsp90 drives a molecular ‘clamp’ via transient dimerization of the N-terminal domains. Embo J. 2000;19:4383–4392. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C, Roe SM, O’Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH. Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell. 1997a;90:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodromou C, Roe SM, Piper PW, Pearl LH. A molecular clamp in the crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of the yeast Hsp90 chaperone. Nat Struct Biol. 1997b;4:477–482. doi: 10.1038/nsb0697-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randow F, Seed B. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone gp96 is required for innate immunity but not cell viability. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:891–896. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed RC, Zheng T, Nicchitta CV. GRP94-associated enzymatic activities. Resolution by chromatographic fractionation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25082–25089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser MF, Nicchitta CV. Ligand interactions in the adenosine nucleotide-binding domain of the Hsp90 chaperone, GRP94. I. Evidence for allosteric regulation of ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22798–22805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001477200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp S, Workman P. Inhibitors of the HSP90 molecular chaperone: current status. Adv Cancer Res. 2006;95:323–348. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)95009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau AK, Harris SF, Southworth DR, Agard DA. Structural Analysis of E. coli hsp90 reveals dramatic nucleotide-dependent conformational rearrangements. Cell. 2006;127:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldano KL, Jivan A, Nicchitta CV, Gewirth DT. Structure of the N-terminal domain of GRP94. Basis for ligand specificity and regulation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48330–48338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoilova D, Dai J, de Crom R, van Haperen R, Li Z. Haplosufficiency or functional redundancy of a heat shock protein gp96 gene in the adaptive immune response. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2000;5:395. [Google Scholar]

- Van PN, Peter F, Soling HD. Four intracisternal calcium-binding glycoproteins from rat liver microsomes with high affinity for calcium. No indication for calsequestrin-like proteins in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive calcium sequestering rat liver vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17494–17501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CK, Gohlke U, Sobott F, Good VM, Ali MM, Prodromou C, Robinson CV, Saibil HR, Pearl LH. Structure of an hsp90-cdc37-cdk4 complex. Mol Cell. 2006;23:697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wearsch PA, Nicchitta CV. Interaction of endoplasmic reticulum chaperone GRP94 with peptide substrates is adenine nucleotide-independent. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5152–5156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.5152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegele H, Muschler P, Bunck M, Reinstein J, Buchner J. Dissection of the contribution of individual domains to the ATPase mechanism of Hsp90. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39303–39310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigley DB, Davies GJ, Dodson EJ, Maxwell A, Dodson G. Crystal structure of an N-terminal fragment of the DNA gyrase B protein. Nature. 1991;351:624–629. doi: 10.1038/351624a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Liu B, Dai J, Srivastava PK, Zammit DJ, Lefrancois L, Li Z. Heat shock protein gp96 is a master chaperone for toll-like receptors and is important in the innate function of macrophages. Immunity. 2007;26:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- Purification, Crystallization, Structure Solution, and ATPase assay methods

- Figure S1: Initial M.A.D. electron density maps for the GRP94-NMC-AMPPNP complex and the GRP94-MC structure.

- Figure S2: Representative electron density and crystallographic data quality for the GRP94-NMC-ADP/AMPPNP complexes.

- Figure S3: Representative electron density and crystallographic data quality for the apo GRP94-NM and GRP94-MC structures.

- Table S1: Data collection and refinement statistics, GRP94-NMC

- Table S2: Data collection and refinement statistics, GRP94-NM, GRP94-MC

- Table S3: Summary of Kinetic data

- Sequence alignments