Abstract

In developing countries, hepatitis E (HEV) and hepatitis A (HAV) are the major causes of acute viral hepatitis with similar fecooral modes of transmission. In contrast to the high seroprevalence of hepatitis A infection, a low seroprevalence of HEV among children in endemic areas has been reported. These data suggest the possibility that silent HEV infection is undiagnosed by the current available methods. Many of the serological tests used for HEV diagnosis have poor specificity and are unable to differentiate among different genotypes of HEV. Moreover, the RT-PCR used for HEV isolation is only valid for a brief period during the acute stage of infection. Cell-mediated immune (CMI) responses are highly sensitive, and long lasting after sub-clinical infections as shown in HCV and HIV. Our objective was to develop a quantitative assay for cell-mediated immune (CMI) responses in HEV infection as a surrogate marker for HEV exposure in silent infection. Quantitative assessment of the CMI responses in HEV will also help us to evaluate the role of CMI in HEV morbidity. In this study, an HEV-specific interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) ELISPOT assay was optimized to analyze HEV-specific CMI responses. We used peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and sera from experimentally infected chimpanzees and from seroconverted and control human subjects to validate the assay. The HEV-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT responses correlated strongly and significantly with anti-HEV ELISA positive/negative results (rho=0.73, p=0.02). Moreover, fine specificities of HEV-specific T cell responses could be identified using overlapping HEV ORF2 peptides.

Keywords: HEV, ELISPOT, Immunity, Hepatitis E, Cell-mediated, Diagnosis

1. Introduction

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is a common cause of acute symptomatic viral hepatitis (AVH) in developing countries (Skidmore et al., 1992). It is transmitted by the fecal-oral route, and water-borne outbreaks have been reported frequently. HEV does not cause chronic hepatitis and full recovery is common; however, mortality rates of 0.5-4% in the general population and up to 20% among pregnant women have been reported (Emerson and Purcell, 2003). The mechanisms for this high HEV morbidity in pregnant women are largely unknown. HEV infection was believed to be limited in the US to travelers; however, zoonotic reservoirs and the potential for transmission are present (Halbur et al., 2001). The prevalence of antibodies to HEV (anti-HEV) is as high as 20% among blood donors in certain areas in the US (Meng et al., 2002). However, HEV-caused AVH is very rare in the US. A similar situation exists in Egypt where up to 80% of the inhabitants of rural villages have anti-HEV with very little or no evidence that the infection causes acute hepatitis in the subjects in these community-based studies (Fix et al., 2000; Meky et al., 2006; Stoszek et al., 2006), although, just as in the US, sporadic cases of acute hepatitis E infections are reported (Zakaria et al., 2007). The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear.

Markers for either prior exposure, or current infection with HEV include enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing for anti-HEV IgG and IgM, and RT-PCR detection of HEV-RNA. In AVH cases caused by HEV, anti-HEV IgM is usually positive for a few weeks. Additionally, HEV-RNA may be detected in the blood or stool from up to 50% of anti-HEV IgM positive cases (El-Sayed Zaki et al., 2006). However, these tests have not been as reliable as similar tests for hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) (Bryan et al., 1994; Dawson et al., 1992; Favorov et al., 1992; Goldsmith et al., 1992). Until recently, commercial tests for anti-HEV IgG have demonstrated inconsistent sensitivity and specificity. The in-house NIH assay used in this study has higher sensitivity when compared with commercial assays (Engle et al., 2002; Fix et al., 2000; Ghabrah et al., 1998; Mast et al., 1998). In fact, community-based surveys in 6000 subjects demonstrated that different lots of a commercial anti-HEV IgG ELISA varied considerably (for example, a second lot increased community-wide prevalence by 25% from 60-to-85%) (Fix et al., 2000). This may be attributed to the fact that the NIH assay uses a recombinant ORF2-derived capture antigen that has a higher sensitivity for both genotypes 1 and 3 (Engle et al., 2002). The commercial assays may detect acute and recent infections, but are not able to detect more remote infections with high sensitivity, as is often needed in epidemiological studies (Mast et al., 1998).

In addition to the challenges of assessing anti-HEV IgG, there has not been a reliable test for detecting anti-HEV IgM in the past. However, a recently available commercial assay for anti-HEV IgM (HEV-IgM ELISA 3.0, MP Diagnostics, formerly Genelabs Diagnostic, Singapore) appears promising for detecting acute HEV infections (Chen et al., 2005). Anti-IgM peaks up to four weeks after onset of AVH and is no longer detectable in half of the cases after three months (Arankalle et al., 1994; Bryan et al., 1994; Dawson et al., 1992). Additionally, it is not known how long anti-IgG persists because of differences in sensitivity of the EIA. Therefore, humoral immune responses used for the diagnosis of acute infection or to identify prior exposure to HEV have poor sensitivity and specificity. Additionally, serological assays are not useful for differentiating among HEV genotypes. Sequencing of HEV-RNA is required to separate genotypes but its sensitivity depends upon a proper match between the HEV strain and the PCR primers.(Schlauder et al., 1999) The primers used, usually ORF1, ORF2, and an ORF2/3 combination, in the RT-PCR are critical since they may be genotype-specific in their sensitivity.

CMI responses to sub-clinical infection without seroconversion have been reported in HCV (Al-Sherbiny et al., 2005; Freeman et al., 2004; Post et al., 2004; Semmo et al., 2005; Shata et al., 2003b), and HIV (Alimonti et al., 2006; Clerici and Shearer, 1996; Dittmer et al., 1996; Fowke et al., 1996; Kaul et al., 2004) infections. Memory CMI responses are also long lasting and could be detected up to 20-30 years after exposure despite the decrease of humoral immune responses.(Takaki et al., 2000) To determine whether CMI immune response to HEV could be used as a surrogate marker for exposure, and to study the CMI roles in HEV morbidity, we developed a highly sensitive assay to measure CMI responses in HEV infections. We optimized an HEV-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as a marker for exposure to HEV, using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from chimpanzees experimentally infected with HEV, as well as samples from our human subjects in Egypt, and the US. In this study, we also identified the fine specificity of ORF-2-specific T cell memory responses from an HEV-infected asymptomatic human subject.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Samples

2.1.1. Chimpanzees

12 juvenile chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) derived from a hepatitis virus-free colony were used in the study. The animals were housed at Bioqual Inc. (Rockville, Maryland, USA), and maintained according to American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) guidelines. Six of the animals had been experimentally infected with HEV, and cleared the infection, three to four years prior to collection of lymphocytes for the present study. All six were positive for IgG anti-HEV. The studies performed with these animals had been approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of Bioqual Inc. and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Bethesda, Maryland, USA). All of the animals had been infected with the SAR-55 strain of HEV, a genotype 1 virus recovered from an epidemic of hepatitis E in Pakistan. The other six chimpanzees were naïve and negative for anti-HEV and were used as controls.

2.1.2. Human subjects

15-20 ml of blood and 2 ml of sera from 19 seronegative control subjects and 12 anti-HEV IgG positive subjects were collected after obtaining informed consent.

2.2. Antigens

2.2.1. HEV ORF2 protein

ORF2 protein was expressed in insect cells from a recombinant baculovirus vector (Robinson et al., 1998), and used for ELISA and ELISPOT assay as described below.

2.2.2. HEV ORF2 overlapping peptides

A total of 68 16-mer peptides, overlapping by 8 amino acids, representing aa 111-660 of ORF2 from the SAR-55 strain of HEV (PSSM-ID: 42949) were synthesized and used in the assay at a concentration of 1-10 μg/ml. Pooled peptide stocks were used at a concentration equivalent to 1 μg/ml of the individual peptides in the pool.

2.2.3. Phytohemagglutinin-L (PHA-L)

Phytohemagglutinin-L (PHA-L) (Sigma, MO) was used as a positive control at a concentration of 1-5 μg/ml.

2.3. Enzyme linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assay

We used a modification of the ELISA assay as previously described (Engle et al., 2002). Polystyrene microwell plates (catalog no. 76-381-04; ICN, Costa Mesa, CA.) were incubated with ORF2 antigen diluted in a carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) for 18 h at room temperature. The antigen concentration was 0.05 μg/well. The wells were washed twice in an automated plate washer with a commercially available wash solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Lab., Gaithersburg, MD.) containing 0.02% Tween 20 in 0.002 M imidazole-buffered saline. The wells were blocked with bovine serum albumin-gelatin at 37 °C. After 1 h, the blocking buffer was removed and the plates were washed twice with wash buffer. Ten microliters of each test and control sample was diluted at a ratio of 1:10. The sample was further diluted at a ratio of 1:10 into an antigen-coated test plate (final test dilution, 1:100) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Wells were washed five times, and 100 μl of 1.0 μg/ml of horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-human IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry Lab., Gaithersburg, MD.) was added to each well. Following a 30-minute incubation at 37 °C, unbound conjugate was removed by washing five times. 2,2′-azino-di-[3-ethyl-benzthiazoline sulfate] (ABTS) substrate was added for color development, and absorbance (405 nm) was read after 30 min. The cutoff for the assay was established for each test from internal controls. Previously tested anti-HEV negative blood bank samples, and dilution buffer served as negative controls.

2.4. Isolation and propagation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC)

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) drawn from chimpanzees convalescent from experimental HEV infection and from control chimpanzees as well as from human volunteers were purified by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation and either used fresh or cryopreserved at -70 °C in 90% serum and 10% DMSO. Before performing any assay, cryopreserved PBMC were thawed, washed three times, and counted. To control for the effects of freezing and thawing, freshly isolated and freeze/thawed PBMC were tested in parallel. The tested antigens induced a comparable number of spots in ELISPOT assays with frozen and fresh PBMC (data not shown). Additionally, to eliminate samples with poor viability, those having PHA responses <1000 ISC/106 cells were excluded from analysis. The average numbers of IFN-γ-secreting cells (ISC)/106 cells in six chimpanzees, and 31 human subjects after PHA stimulation, was 2275 ± 750 ISC/106 cells.

2.5. Interferon-γ ELISPOT assay

ELISPOT assay was performed with the γ-IFN ELISPOT Kit (MABTECH Cat No M34201-A, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 96-well nitrocellulose bottomed plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA) were coated with murine anti-human IFN-γ mAb at a concentration of 15 μg/ml in PBS, and incubated at 4 °C. After 24 h, the plates were washed and blocked with 10% human AB+ serum (1 h at 37 °C). To estimate the number of HEV-specific interferon-γ secreting cells (ISC), PBMC were added at different concentrations (104-105 cells/well) in a 100 μl volume of complete medium (RPMI-1640 containing 10% AB+ serum). For stimulation, PBMC were pulsed with the test peptides or HEV ORF2 protein at 1-5 μg/ml as described (Shata et al., 2002, 2003b). After an 18-hour incubation at 37 °C, the plates were washed 5 times with washing buffer (PBS containing 0.5% (v/v) Tween 20; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Biotinylated anti-human IFN-γ mAb (clone 4S.B3) at a concentration of 1 μg/ml in dilution buffer (PBS containing 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Plates were then washed again 5 times, and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:1000) in dilution buffer was added and incubated at room temperature for 2 h, followed by washing five times with washing buffer and the addition of the substrate 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (AEC) reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). After developing the spots for 10-15 min, the plates were washed with distilled water and air-dried. The number of spots was enumerated using an automated ELISPOT 3B analyzer (CTL, Cleveland, OH) designed to detect spots with predetermined criteria based on size, shape and colorimetric density, and expressed per 106 cells. Results were calculated from the equation:

HEV-specific ISC was plotted after subtracting the number of ISC induced by control peptides or no stimulation. The cutoff level of ISC was calculated as the average number of ISC in the presence of medium + 2SD.

2.6. Propagation of HEV-specific T cell lines

An HEV-specific T cell line was propagated from PBMC isolated from an asymptomatic human subject (donor 1) who was positive for anti-HEV of the IgG but not IgM class. PBMC were stimulated with pooled HEV ORF2 peptides at a concentration equivalent to 1 μg/ml for each peptide and HEV ORF2 protein at a concentration of 2 μg/ml to stimulate both CD4 and CD8-HEV specific T cells. After 2 weeks, the cells were rested for a week, and restimulated with Recombinant Human IL-2 (Cell Sciences, MA), IL-7 and IL-15 (Endogen, MA) at a concentration of 50, 1, and 1 IU/ml respectively. The addition of IL-7 and IL-15 increases the sensitivity of the assay to detect memory T cells (Jennes et al., 2002). The cycle of stimulation was repeated 3 times using irradiated autologous PBMC as antigen presenting cells. After 8 weeks, a 1-2 log enrichment of the frequency of HEV ORF2-specific T cells was observed by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The analysis of ELISPOT data was performed using Fisher’s Exact test or Pearson’s chi-square test as appropriate. The relationship between optical densities and ELISPOT results was examined in human subjects via Spearman rank correlation. A nonparametric receiver-operator characteristic curve (ROC) was used to determine the capacity of optical densities to predict ELISA results. Statistical analyses were conducted in Stata version 8.2 (Stata Corp., College Station,TX). In all cases, two-tailed p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Development of Ag-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assay to measure CMI responses in chimpanzees experimentally infected with HEV

PBMC from 6 chimpanzees convalescent from HEV infection and PBMC from 6 control chimpanzees were used to establish and standardize an HEV-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assay.

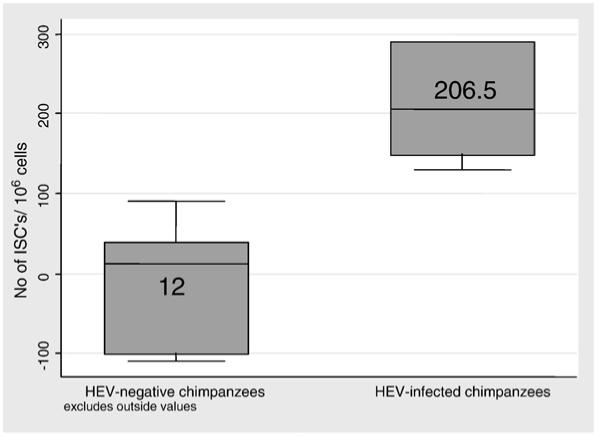

As seen in Fig. 1, the numbers of HEV specific T cell responses in the HEV-infected chimpanzees in the presence of IL-7 and IL-15 were significantly higher (p<0.001) than that of the uninfected chimpanzees (mean ± standard deviation (SD)=764.2 ± 1210, and 0 ± 80.2 ISC/106 cells, and median=206.5 and 12 ISC/106 cells; respectively).

Fig. 1.

Box and Whisker plot of responses of HEV infected and uninfected chimpanzees to HEV. PBMC from HEV-convalescent chimpanzees (n=6) or control chimpanzees (n=6) were examined by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay in the presence of IL-7 and IL-15 as described in the Methods section using HEV ORF2 protein at a concentration of 5 μg/ml, or pooled HEV ORF2 peptides at a concentration equivalent to 1 μg/ml of individual peptide. PHA stimulation was used as a positive control. Data are presented as the number of ISC with HEV stimulation after subtraction of the background (no stimulus). Boxes represent the 25%-75% interquartile (IQR) range of data. Whiskers represent the next adjacent values to the IQR. The middle line in the box is the median value. The differences between the two groups are significant (p<0.001).

3.2. Characterization of humoral and cellular immune responses in HEV-infected and control subjects

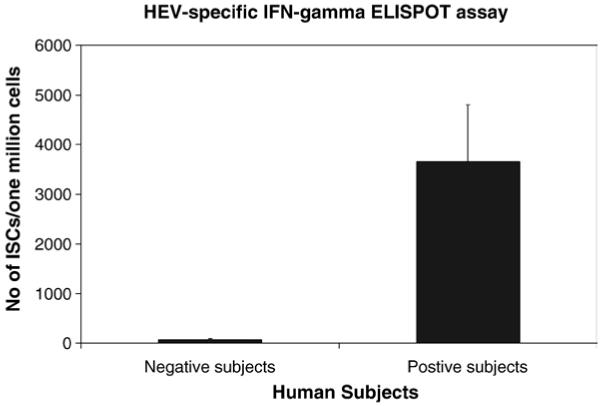

To evaluate the utility of the HEV-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assay in the diagnosis of HEV infection in humans, sera and PBMC from 22 volunteers from the US, and 9 anti-HEV IgG positive subjects from an HEV-endemic area (Egypt), were tested with ELISA and ELISPOT assay. Three volunteers from the US tested positive for anti-HEV IgG, but not IgM. One of them (donor 1) had a history of traveling to Egypt. All other volunteers were negative for anti-HEV. The PBMC of these 31 subjects were tested for HEV-specific IFN-γ T cell responses using ELISPOT assay. As shown in Fig. 2, anti-HEV positive subjects by ELISA showed strong IFN-γ responses upon stimulation with pooled HEV ORF2 peptides in comparison to the anti-HEV ELISA negative donors (mean ± SD=628.2 ± 982.5 and 9.7 ± 18.8 ISC/106 cells, and median=1 and 373 ISC/106 cells; respectively). This difference was statistically significant (p=0.001).

Fig. 2.

Anti-HEV positive subjects show strong IFN-γ responses upon stimulation with pooled HEV ORF2 peptides. PBMC withdrawn from 19 seronegative and 12 seropositive HEV subjects were examined by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as described in the Methods section using pooled HEV ORF2 peptides at a concentration equivalent to 1 μg/ml of individual peptide. PHA stimulation was used as a positive control (not shown). Data are presented as the increase in the number of ISC in the presence of HEV ORF2 peptides after subtraction of the background (no stimulus). The differences between the two groups are significant (p=0.001).

The relationship between HEV-specific interferon-γ ELISPOT responses and ELISA results was strong and statistically significant (Spearman’s rho=0.73, p=0.02). To determine the capacity of ELISPOT responses to predict when binary (positive/negative) ELISA results, the area under the ROC curve (AUROC) was assessed. ELISPOT responses >67.5 were perfectly predictive of positive results (area under the ROC curve (AUROC))=1.00. One human subject had an indeterminate ELISA result; when this was interpreted as a negative result, the AUROC was 0.92 (standard error 0.09). This relationship was observed for subgroups of humans and chimpanzees.

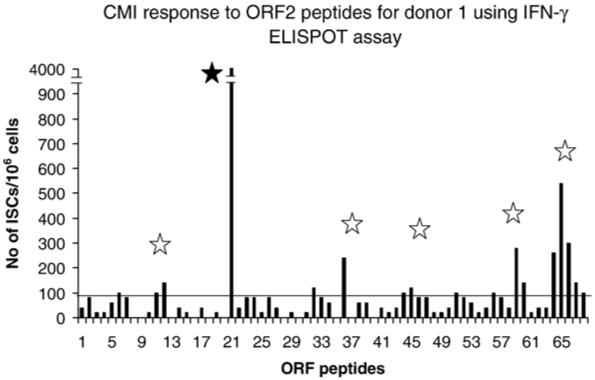

3.3. Epitope mapping of HEV-specific immune responses using IFN-γ ELISPOT assay

Fine HEV specificity of the PBMC from donor 1 was evaluated using individual HEV ORF2 16-mer peptides. Dominant [peptide 21, (ATSGLVMLCIHGSPVN)], and subdominant epitopes [peptide 12 (PNAVGGYAISISFWPQ), peptide 37 (RPVVSANGEPTVKLYT), peptide 45 (SVLRANDVLWLSLTAA), peptide 60 (TYTTSLGAGPVSISAV), and peptide 66 (RPLGLQGCAFQSTVAE)] were identified as shown in Fig. 3. Predicted binding of the ORF2 sequence of genotype 1 to HLA DRB1_0402 (the HLA type of donor 1) was examined using the web site http://www.imtech.res.in., and is in agreement with our data.

Fig. 3.

Dominant and subdominant epitopes in HEV ORF 2 protein. PBMC from donor 1 were examined by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay using 16-mer overlapping HEV ORF2 peptides at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. Data are presented as the number of ISC in the presence of individual ORF2 HEV peptides. One dominant (P21), closed star, and 5 subdominant (P12, P37, P45, P60, and P66), open stars, epitopes were identified.

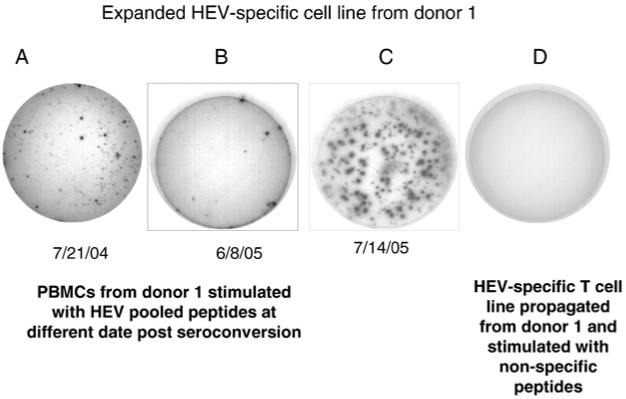

3.4. Detection of HEV-specific memory responses with IFN-γ ELISPOT assay

PBMC from donor 1, obtained 14 months (on 6/05) after traveling to Egypt, were examined for HEV-specific memory responses using IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. As shown in Fig. 4, a low level of HEV-specific T cell responses could still be demonstrated in the presence of IL-7 and IL-15 cytokines in comparison to the earlier responses (on 7/21/04) (420, and 1295 ISC/106 cells, respectively). An HEV-specific cell line was propagated from PBMC (drawn on 6/8/05) and repeatedly stimulated with HEV ORF2 protein and pooled peptides. As shown in Fig. 4, 8 weeks after 3 cycles of stimulation, the frequency of HEV-specific T cells had increased approximately 20 fold (7637.5 ISC/106 cells).

Fig. 4.

HEV-specific memory responses. PBMC drawn at different times from donor 1 were examined by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as described in the Methods section. Data are presented as the IFN-γ ELISPOT responses in the wells. Well A is ex-vivo HEV IFN-γ response of donor 1 (PBMC obtained 3 months after returning from endemic area). Well B is ex-vivo HEV IFN-γ response for donor 1 (PBMC obtained 14 months after returning from endemic area). Well C is IFN-γ ELISPOT response for HEV specific T cell line originating from cells used in well B, and propagated by in vitro stimulation with HEV peptides and proteins for 6 weeks. Well D is the ELISPOT response of HEV specific T cell line to non-specific peptides.

4. Discussion

HEV accounts for 30-60% of sporadic hepatitis in the Indian subcontinent. HEV is not only a problem in developing countries but has also become a concern of developed countries (Christensen et al., 2002; Clemente-Casares et al., 2003; Fukuda et al., 2004). The high seroprevalence despite the rarity of disease morbidity in the developed countries is still unexplained (Meng et al., 2002). Different theories have been suggested to explain this discrepancy including exposure to avirulent strains, infection with zoonotic strains of HEV with low virulence, the presence of protective cross-reactive immune responses to virulent HEV strains or low specificity of the serological tests. However, there are limited data to support any of these hypotheses.

A recent report has suggested that CMI responses and Th1/Th2 cytokine profiles in pregnant women are highly involved in HEV morbidity (Pal et al., 2005). To address the role of the CMI response in HEV infection, a quantitative assay for measuring HEV-specific CMI responses is needed. Prior reports examined T cell proliferation (Aggarwal et al., 2007; Naik et al., 2002; Pal et al., 2005; Srivastava et al., 2007) or flow cytometry (Srivastava et al., 2007) as a surrogate marker for CMI responses to HEV, however, the sensitivity and specificity of these assays were low. During the last ten years, highly sensitive IFN-γ ELISPOT assays have been used successfully for measuring the CMI responses in different diseases (Dheda et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2003). ELISPOT assays detect Ag-specific T cells at frequencies as low as 1:100,000 (Lalvani et al., 1997; McCutcheon et al., 1997). Our laboratory has optimized and standardized IFN-γ ELISPOT assays to measure CMI in viral hepatitis caused by HCV and HBV, both in humans and in chimpanzees (Al-Sherbiny et al., 2005; Farid et al., 2005; Shata et al., 2002, 2006, 2003a). In the current study, we evaluated the usage of IFN-γ ELISPOT assay in measuring CMI responses in HEV infections.

The chimpanzee is a suitable animal model for understanding HEV pathogenesis (Meng et al., 1998; Purcell and Emerson, 2001; Yu et al., 2003). Our access to PBMC from experimentally HEV-infected and control chimpanzees helped us to develop and standardize an HEV-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as a measurement for cell-mediated immune response. Our data suggest that the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay may be used to quantitatively evaluate CMI responses in HEV infection. We noticed that CMI responses to HEV in the convalescent chimpanzees were still detectable 3-4 years after infection despite the absence of chronicity in HEV infection. Previous reports support the presence of long-lived CMI responses after viral infection (Deliyannis et al., 2002; Effros, 2000; Van Epps et al., 2002) and vaccination (Hammarlund et al., 2003). Addition of IL-7 and IL-15, cytokines which specifically stimulate memory responses (Guimond et al., 2005; Jennes et al., 2002), significantly increased the frequency of Ag-specific T cells in these convalescent chimpanzees.

To evaluate the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay in the diagnosis of HEV infection in humans, PBMC from HEV-infected, and control human subjects were examined. PBMC from 12 seropositive and from 19 seronegative subjects were stimulated with pooled HEV ORF2 peptides. Seropositive subjects had strong IFN-γ ELISPOT responses to the HEV ORF2 peptides in comparison to the anti-HEV negative control subjects. However, one of the subjects from the US (donor 1) showed a strong HEV-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT response and a strong IgG, but not IgM, anti-HEV response in ELISA assays. Donor 1 had traveled to Egypt two months prior to participation in the study. He had no history of jaundice or fever, suggesting asymptomatic infection. It is not clear if donor 1 had been exposed to HEV during his recent visit to Egypt, or previously, since he had lived in Egypt for 40 years before moving to the US 10 years ago. PBMC and sera from donor 1 have been tested frequently (every 3-6 months) for CMI and humoral responses to HEV for two years following his most recent visit to Egypt. The levels of anti-HEV IgG in sera of donor 1 have persisted with little or no change (data not shown) during those intervals. Although there were decreases in the magnitude of CMI responses during those intervals as measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay, the sensitivity of the assay could be partially restored with the addition of IL-7 and IL-15 cytokines. These data suggest that the strong HEV-specific ELISPOT response shown on 7/21/04 (Fig. 4) was a consequence of re-exposure or new infection to HEV and not a result of a previous infection during childhood.

Dominant and subdominant epitopes of ORF2 protein have been identified in donor 1. Analysis of the predictive binding capacity of the HLA revealed strong agreement between the predictive binding capacity of ORF2 peptides to the DRB1_0402 (the HLA of donor 1), and the ORF2 dominant and subdominant epitopes recognized by donor 1. Phenotypic and functional analysis of the HEV-specific T cell line revealed that it is CD3+ CD4+ with the ability to secrete IFN-γ upon stimulation with HEV pooled peptides (data not shown). Additionally, we were unable to identify HEV-specific CD8+ T cells, probably due to the usage of 16-mer peptides and HEV protein in the propagation of the HEV-specific T cell line. Long peptides (>15 mer), and protein antigens preferentially stimulate CD4+ T cells (Appella et al., 1995).

The anti-HEV IgG ELISA assay used in this study is highly sensitive for diagnosing HEV infections. It is also highly efficient for detecting old infections, both in humans and chimpanzees. One of the challenges with current anti-HEV IgG ELISA assays is their failure to distinguish between infection with different genotypes of HEV (Zhou et al., 2004). Theoretically, the ELISPOT assay may be able to distinguish the genotypes of the infecting strains of HEV depending on the unique epitopes recognized by T cells, especially if peptides from a highly variable protein like ORF3 are used instead of the more conserved ORF2 protein. Additionally, with ELISPOT assay, we will have the tool to study the role of CMI in HEV infection during pregnancy and in AVH patients.

Our laboratory is currently applying the methodology to large numbers of HEV-exposed and infected individuals in Egypt to evaluate the specificity and the sensitivity of the assay in highly endemic areas. Additionally, the role of cross-reactive responses in protection against virulent strains of HEV in areas of high HEV morbidity (India), and in areas of low HEV morbidity despite medium to high seroprevalence (the US and Egypt,, respectively) will be examined.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the NIH grant R21AI067868 (Shata), K24DK070528 (Sherman), the Wellcome Trust-Burroughs Wellcome Fund grants 059113/z/99/a and 059113/z/99/z, and by the NIH International Collaborations in Infectious Disease Research (ICIDR) grant number U01AI058372 (Strickland), and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID (Purcell).

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the 12th International Symposium on Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease in Paris, July 2006, Abstract No P312.

References

- Aggarwal R, Shukla R, Jameel S, Agrawal S, Puri P, Gupta VK, Patil AP, Naik S. T-cell epitope mapping of ORF2 and ORF3 proteins of human hepatitis E virus. J. Viral Hepatitis. 2007;14(4):283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alimonti JB, Kimani J, Matu L, Wachihi C, Kaul R, Plummer FA, Fowke KR. Characterization of CD8 T-cell responses in HIV-1-exposed seronegative commercial sex workers from Nairobi, Kenya. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2006;84(5):482. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2006.01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sherbiny M, Osman A, Mohamed N, Shata MT, Abdel-Aziz F, Abdel-Hamid M, Abdelwahab SF, Mikhail N, Stoszek S, Ruggeri L, Folgori A, Nicosia A, Prince AM, Strickland GT. Exposure to hepatitis C virus induces cellular immune responses without detectable viremia or seroconversion. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005;73(1):44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appella E, Padlan EA, Hunt DF. Analysis of the structure of naturally processed peptides bound by class I and class II major histocompatibility complex molecules. Exs. 1995;73:105. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9061-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arankalle VA, Goverdhan MK, Banerjee K. Antibodies against hepatitis E virus in Old World monkeys. J. Viral Hepatitis. 1994;1(2):125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.1994.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan JP, Tsarev SA, Iqbal M, Ticehurst J, Emerson S, Ahmed A, Duncan J, Rafiqui AR, Malik IA, Purcell RH, et al. Epidemic hepatitis E in Pakistan: patterns of serologic response and evidence that antibody to hepatitis E virus protects against disease. J. Infect. Dis. 1994;170(3):517. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HY, Lu Y, Howard T, Anderson D, Fong PY, Hu WP, Chia CP, Guan M. Comparison of a new immunochromatographic test to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for rapid detection of immunoglobulin m antibodies to hepatitis e virus in human sera. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2005;12(5):593. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.5.593-598.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen PB, Engle RE, Jacobsen SE, Krarup HB, Georgsen J, Purcell RH. High prevalence of hepatitis E antibodies among Danish prisoners and drug users. J. Med. Virol. 2002;66(1):49. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Casares P, Pina S, Buti M, Jardi R, MartIn M, Bofill-Mas S, Girones R. Hepatitis E virus epidemiology in industrialized countries. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2003;9(4):448. doi: 10.3201/eid0904.020351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici M, Shearer GM. Correlates of protection in HIV infection and the progression of HIV infection to AIDS. Immunol. Lett. 1996;51(1-2):69. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02557-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson GJ, Chau KH, Cabal CM, Yarbough PO, Reyes GR, Mushahwar IK. Solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for hepatitis E virus IgG and IgM antibodies utilizing recombinant antigens and synthetic peptides. J. Virol. Methods. 1992;38(1):175. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(92)90180-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliyannis G, Jackson DC, Ede NJ, Zeng W, Hourdakis I, Sakabetis E, Brown LE. Induction of long-term memory CD8(+) T cells for recall of viral clearing responses against influenza virus. J. Virol. 2002;76(9):4212. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4212-4221.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dheda K, Lalvani A, Miller RF, Scott G, Booth H, Johnson MA, Zumla A, Rook GA. Performance of a T-cell-based diagnostic test for tuberculosis infection in HIV-infected individuals is independent of CD4 cell count. Aids. 2005;19(17):2038. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191923.08938.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer U, Spring M, Petry H, Nisslein T, Rieckmann P, Luke W, Stahl-Hennig C, Hunsmann G, Bodemer W. Cell-mediated immune response of macaques immunized with low doses of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) J. Biotechnol. 1996;44(1-3):105. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(95)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effros RB. Long-term immunological memory against viruses. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2000;121(1-3):161. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed Zaki M, El-Deen Zaghloul MH, El Sayed O. Acute sporadic hepatitis E in children: diagnostic relevance of specific immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G compared with nested reverse transcriptase PCR. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2006;48(1):16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E virus. Rev. Med. Virol. 2003;13(3):145. doi: 10.1002/rmv.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle RE, Yu C, Emerson SU, Meng XJ, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E virus (HEV) capsid antigens derived from viruses of human and swine origin are equally efficient for detecting anti-HEV by enzyme immunoassay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40(12):4576. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4576-4580.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farid A, Al-Sherbiny M, Osman A, Mohamed N, Saad A, Shata MT, Lee DH, Prince AM, Strickland GT. Schistosoma infection inhibits cellular immune responses to core HCV peptides. Parasite Immunol. 2005;27(5):189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2005.00762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favorov MO, Fields HA, Purdy MA, Yashina TL, Aleksandrov AG, Alter MJ, Yarasheva DM, Bradley DW, Margolis HS. Serologic identification of hepatitis E virus infections in epidemic and endemic settings. J. Med. Virol. 1992;36(4):246. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fix AD, Abdel-Hamid M, Purcell RH, Shehata MH, Abdel-Aziz F, Mikhail N, el Sebai H, Nafeh M, Habib M, Arthur RR, Emerson SU, Strickland GT. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E in two rural Egyptian communities. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000;62(4):519. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowke KR, Nagelkerke NJ, Kimani J, Simonsen JN, Anzala AO, Bwayo JJ, MacDonald KS, Ngugi EN, Plummer FA. Resistance to HIV-1 infection among persistently seronegative prostitutes in Nairobi, Kenya. Lancet. 1996;348(9038):1347. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)12269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman AJ, Ffrench RA, Post JJ, Harvey CE, Gilmour SJ, White PA, Marinos G, Van Beek I, Rawlinson WD, Lloyd AR. Prevalence of production of virus-specific interferon-gamma among seronegative hepatitis C-resistant subjects reporting injection drug use. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;190(6):1093. doi: 10.1086/422605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S, Sunaga J, Saito N, Fujimura K, Itoh Y, Sasaki M, Tsuda F, Takahashi M, Nishizawa T, Okamoto H. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E virus among Japanese blood donors: identification of three blood donors infected with a genotype 3 hepatitis E virus. J. Med. Virol. 2004;73(4):554. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghabrah TM, Tsarev S, Yarbough PO, Emerson SU, Strickland GT, Purcell RH. Comparison of tests for antibody to hepatitis E virus. J. Med. Virol. 1998;55(2):134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith R, Yarbough PO, Reyes GR, Fry KE, Gabor KA, Kamel M, Zakaria S, Amer S, Gaffar Y. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for diagnosis of acute sporadic hepatitis E in Egyptian children. Lancet. 1992;339(8789):328. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91647-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimond M, Fry TJ, Mackall CL. Cytokine signals in T-cell homeostasis. J. Immunother. 2005;28(4):289. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000165356.03924.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbur PG, Kasorndorkbua C, Gilbert C, Guenette D, Potters MB, Purcell RH, Emerson SU, Toth TE, Meng XJ. Comparative pathogenesis of infection of pigs with hepatitis E viruses recovered from a pig and a human. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001;39(3):918. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.918-923.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarlund E, Lewis MW, Hansen SG, Strelow LI, Nelson JA, Sexton GJ, Hanifin JM, Slifka MK. Duration of antiviral immunity after smallpox vaccination. Nat. Med. 2003;9(9):1131. doi: 10.1038/nm917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennes W, Kestens L, Nixon DF, Shacklett BL. Enhanced ELISPOT detection of antigen-specific T cell responses from cryopreserved specimens with addition of both IL-7 and IL-15—the Amplispot assay. J. Immunol. Methods. 2002;270(1):99. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul R, Rutherford J, Rowland-Jones SL, Kimani J, Onyango JI, Fowke K, MacDonald K, Bwayo JJ, McMichael AJ, Plummer FA. HIV-1 Env-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in exposed, uninfected Kenyan sex workers: a prospective analysis. Aids. 2004;18(15):2087. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalvani A, Brookes R, Hambleton S, Britton WJ, Hill AV, McMichael AJ. Rapid effector function in CD8+ memory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186(6):859. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Singh DK, Sheffer D, Smith MS, Dhillon S, Chebloune Y, Hegde R, Buch S, Narayan O. Immunoprophylaxis against AIDS in macaques with a lentiviral DNA vaccine. Virology. 2006;351(2):444. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast EE, Alter MJ, Holland PV, Purcell RH. Evaluation of assays for antibody to hepatitis E virus by a serum panel. Hepatitis E virus antibody serum panel evaluation group. Hepatology. 1998;27(3):857. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon M, Wehner N, Wensky A, Kushner M, Doan S, Hsiao L, Calabresi P, Ha T, Tran TV, Tate KM, Winkelhake J, Spack EG. A sensitive ELISPOT assay to detect low-frequency human T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. Methods. 1997;210(2):149. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meky FA, Stoszek SK, Abdel-Hamid M, Selim S, Abdel-Wahab A, Mikhail N, El-Kafrawy S, El-Daly M, Abdel-Aziz F, Sharaf S, Mohamed MK, Engle RE, Emerson SU, Purcell RH, Fix AD, Strickland GT. Active surveillance for acute viral hepatitis in rural villages in the Nile Delta. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;42(5):628. doi: 10.1086/500133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng XJ, Halbur PG, Shapiro MS, Govindarajan S, Bruna JD, Mushahwar IK, Purcell RH, Emerson SU. Genetic and experimental evidence for cross-species infection by swine hepatitis E virus. J. Virol. 1998;72(12):9714. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9714-9721.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng XJ, Wiseman B, Elvinger F, Guenette DK, Toth TE, Engle RE, Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis E virus in veterinarians working with swine and in normal blood donors in the United States and other countries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40(1):117. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.1.117-122.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik S, Aggarwal R, Naik SR, Dwivedi S, Talwar S, Tyagi SK, Duhan SD, Coursaget P. Evidence for activation of cellular immune responses in patients with acute hepatitis E. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2002;21(4):149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal R, Aggarwal R, Naik SR, Das V, Das S, Naik S. Immunological alterations in pregnant women with acute hepatitis E. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;20(7):1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post JJ, Pan Y, Freeman AJ, Harvey CE, White PA, Palladinetti P, Haber PS, Marinos G, Levy MH, Kaldor JM, Dolan KA, Ffrench RA, Lloyd AR, Rawlinson WD. Clearance of hepatitis C viremia associated with cellular immunity in the absence of seroconversion in the hepatitis C incidence and transmission in prisons study cohort. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189(10):1846. doi: 10.1086/383279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell RH, Emerson SU. Animal models of hepatitis A and E. ILAR J. 2001;42(2):161. doi: 10.1093/ilar.42.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RA, Burgess WH, Emerson SU, Leibowitz RS, Sosnovtseva SA, Tsarev S, Purcell RH. Structural characterization of recombinant hepatitis E virus ORF2 proteins in baculovirus-infected insect cells. Protein Expr. Purif. 1998;12(1):75. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlauder GG, Desai SM, Zanetti AR, Tassopoulos NC, Mushahwar IK. Novel hepatitis E virus (HEV) isolates from Europe: evidence for additional genotypes of HEV. J. Med. Virol. 1999;57(3):243. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199903)57:3<243::aid-jmv6>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semmo N, Barnes E, Taylor C, Kurtz J, Harcourt G, Smith N, Klenerman P. T-cell responses and previous exposure to hepatitis C virus in indeterminate blood donors. Lancet. 2005;365(9456):327. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shata MT, Anthony DD, Carlson NL, Andrus L, Brotman B, Tricoche N, McCormack P, Prince A. Characterization of the immune response against hepatitis C infection in recovered, and chronically infected chimpanzees. J. Viral Hepatitis. 2002;9(6):400. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shata MT, Shan MM, Tricoche N, Talal A, Perkus M, Prince A. Optimization of recombinant vaccinia-based ELISPOT assay. J. Immunol. Methods. 2003a;283(1-2):281. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shata MT, Tricoche N, Perkus M, Tom D, Brotman B, McCormack P, Pfahler W, Lee DH, Tobler LH, Busch M, Prince AM. Exposure to low infective doses of HCV induces cellular immune responses without consistently detectable viremia or seroconversion in chimpanzees. Virology. 2003b;314(2):601. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00461-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shata MT, Pfahler W, Brotman B, Lee DH, Tricoche N, Murthy K, Prince AM. Attempted therapeutic immunization in a chimpanzee chronic HBV carrier with a high viral load. J. Med. Primatol. 2006;35(3):165. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2006.00152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore SJ, Yarbough PO, Gabor KA, Reyes GR. Hepatitis E virus: the cause of a waterbourne hepatitis outbreak. J. Med. Virol. 1992;37(1):58. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890370110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R, Aggarwal R, Jameel S, Puri P, Gupta VK, Ramesh VS, Bhatia S, Naik S. Cellular immune responses in acute hepatitis e virus infection to the viral open reading frame 2 protein. Viral Immunol. 2007;20(1):56. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoszek S, Engle R, Abdel-Hamid M, Mikhail N, Abdel-Aziz F, Medhat A, Fix AD, Emerson S, Purcell R, Strickland GT. Hepatitis E antibody seroconversion without disease in highly endemic rural Egyptian communities. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;100(2):89. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Iglesias E, Samri A, Kamkamidze G, Decoville T, Carcelain G, Autran B. A systematic comparison of methods to measure HIV-1 specific CD8 Tcells. J. Immunol. Methods. 2003;272(1-2):23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki A, Wiese M, Maertens G, Depla E, Seifert U, Liebetrau A, Miller JL, Manns MP, Rehermann B. Cellular immune responses persist and humoral responses decrease two decades after recovery from a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Nat. Med. 2000;6(5):578. doi: 10.1038/75063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Epps HL, Terajima M, Mustonen J, Arstila TP, Corey EA, Vaheri A, Ennis FA. Long-lived memory T lymphocyte responses after hantavirus infection. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196(5):579. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Engle RE, Bryan JP, Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Detection of immunoglobulin M antibodies to hepatitis E virus by class capture enzyme immunoassay. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2003;10(4):579. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.4.579-586.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria S, Fouad R, Shaker O, Zaki S, Hashem A, El-Kamary SS, Esmat G, Zakaria S. Changing patterns of acute viral hepatitis at a major urban referral center in Egypt. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;44(4):e30. doi: 10.1086/511074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YH, Purcell RH, Emerson SU. An ELISA for putative neutralizing antibodies to hepatitis E virus detects antibodies to genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4. Vaccine. 2004;22(20):2578. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]