Abstract

Information on the influence of poor maternal nutrition on the regulation of responses to pregnancy, placental and fetal growth and development is critical to a better understanding of pregnancy physiology and pathophysiology. We determined normal changes and effects of controlled and monitored moderate nutrient restriction (NR) (global nutrient intake reduced to 70% of food consumed by mothers feeding ad libitum from 0.16 to 0.5 of gestation) in the baboon, on important hematological, biochemical, and hormonal indices of fetal growth and placental function. Serum IGF-I:IGFBP-3 ratio was lower in pregnant than control non-pregnant baboons feeding ad libitum. Serum concentrations of total and free IGF-I were decreased in NR mothers compared with controls (p < 0.05). The decrease in fetal IGF-I did not reach significance (p = 0.057). Serum IGF-I: IGFBP-3 ratio was decreased by NR in both mothers and fetuses. Maternal serum IGF-II was unchanged by NR. Placental IGF-I mRNA and protein abundance were similarly reduced whereas IGF-II mRNA increased in placental tissue of NR compared to control mothers. Systemic (maternal) and local (placental) IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-3 mRNA and protein abundance were unchanged by NR. Type 1 IGF receptor protein in the syncytiotrophoblast increased in NR. Type 2 IGF receptor protein was present in the stem villi core, and decreased after NR. We conclude that moderate NR in this important non-human primate model significantly disrupts the maternal and placental IGF-IGFBP axis and influences placental expression of this key system at the gene and protein level. Changes observed appear to be directed toward preserving placental growth.

Keywords: Placenta, IGF system, Maternal nutrient restriction, Baboon

1. Introduction

Placental nutrient transport from mother to fetus is essential for placental and fetal growth [1]. The fetus regulates placental function through signals it sends to the placenta. Insulin-like growth factors (IGFs: IGF-I and -II), high affinity IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs), and related IGF receptors (IGF-1R and IGF-2R) comprise part of the complex communication network between mother, placenta, and fetus [2]. IGFs influence autocrine and paracrine regulation of cell proliferation, migration, and survival. The placental IGF-IGFBP-receptor axis is a major influence on placental function and fetal growth [3].

Most circulating IGF arises from hepatocytic synthesis, which is regulated by nutrient availability. Changes in maternal or fetal nutritional status (such as hypoxia or nutrient deprivation) impact both systemic and placental IGF actions (reviewed in ref. [4]). The placental IGF axis has been extensively studied in rats, sheep, horses, guinea pigs and non-human primates [5,6]. However, the placenta differs across species in its structure, conductive and exchange capacities, the mechanisms employed in nutrient exchange (reviewed in ref. [7]), and IGF expression and regulation [8]. Studies conducted in non-human primates improve our understanding of the mechanisms underlying human placental function. Diverse models of maternal nutrient restriction have been reported in a wide range of animals: protein restriction (33–60%) in rats, pigs [9], and rhesus monkeys [10]; micronutrient restriction in rats [11]; and global nutrient restriction (30–100%) in rats, sheep, and guinea pigs. Surprisingly, no data has been reported from non-human primates regarding effects of maternal nutrient restriction on placental IGF and systemic IGF changes. Such data are essential for understanding the mechanisms that promote abnormal fetal growth and maturation in the setting of decreased nutrient availability to the fetus.

The goal of this study was to determine the effects of carefully controlled and monitored restriction of maternal nutrition on the IGF-IGFBP-receptor axis of the pregnant baboon (Papio sp.). Nutrient-restricted mothers were fed 70% of the weight matched food intake consumed by a matched ad libitum fed control group.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

2.1.1. Animal care and maintenance

The pregnant baboons (Papio species)studied belonged to a colony numbering approximately 3800 and maintained by the Southwest National Primate Research Center (SNPRC) at the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research (SFBR, San Antonio, TX). All animals were housed in outdoor metal and concrete gang cages, each containing 10–16 females and 1 male. Details of housing and environmental enrichment have been published elsewhere [12]. All procedures were approved by the SFBR Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.1.2. System for controlling and recording individual feeding

The feeding system used has been described in detail elsewhere [12]. Briefly, once a day prior to feeding, all baboons were run into individual feeding cages. Baboons passed along a chute, over a scale, and into an individual feeding cage. The weight of each baboon was obtained as it crossed an electronic scale system (GSE 665; GSE Scale Systems, MI). The weight recorded was the mean of 50 individual measurements over 3 s. If the standard deviation of the weight measurement was greater than 1% of the mean weight, the weight was automatically discarded, and the weighing procedure was repeated.

Once housed in an individual cage, each animal was fed between either 07:00–09:00 h or 11:00–13:00 h. Water was continuously available in the individual feeding cage and the group cages through individual and group lixits. Animals were fed Purina Monkey Diet 5038 (Purina, St. Louis, MO), described by the vendor as ‘‘a complete life-cycle diet for all Old World Primates.’’ The biscuit contains stabilized vitamin C as well as all other required vitamins. Its basic composition is crude protein not less than 15%, crude fat not less than 5%, crude fiber not more than 6%, ash not more than 5%, and added minerals not more than 3%. At the start of the feeding period, each baboon was given 60 biscuits in the feeding tray of the individual cage. At the end of the 2-h feeding period, the baboons were returned to the group cage. Biscuits remaining in the tray, on the floor of the cage, and in the pan beneath the cage were counted. Food consumption of animals, weights, and health status were recorded each day. The amount of calories, protein, fat and carbohydrates received by the control group in non-pregnant stage and during period of 30–90 days of gestation was 77.4 ± 2.3 kcal/kg per day and 64.3 ± 4.6 kcal/kg per day, 46.2 ± 1.6 g/day and 37.2 ± 2.3 g/day, 33.6 ± 1.1 g/day and 27.1 ± 1.6 g/day, 181.0 ± 6.1 g/day and 145.7 ± 8.8 g/ day respectively. The food consumption of NR group for the non-pregnant and pregnant stages (30–90 days of gestation) were 78.0 ± 3.0 kcal/kg per day and 45.7 ± 1.0 kcal/kg per day, 44.2 ± 2.0 g/day and 24.6 ± 0.8 g/day, 32.2 ± 1.5 g/day and 17.9 ± 0.6 g/day, 173.4 ± 7.8 g/day and 96.6 ± 3.1 g/ day, respectively.

2.1.3. Study design

Fertile female baboons were selected to participate in this study on the basis of their reproductive age (8–15 years old), body weight (10–15 kg), and absence of genital and extragenital pathological signs. Initially, animals were placed into two group cages with a vasectomized male to establish a stable social group [12]. Assignment to the each group was random. At the end of the acclimation period to the group and to feeding in the individual nutritional cages (30 days), a fertile male was introduced into each breeding cage. All baboons were observed twice daily for well-being and three times per week for turgescence (swelling), color of sex skin, and signs of vaginal bleeding to enable timing of ovulation and subsequent conception.

Pregnancy was dated initially by timing of ovulation and changes in sex skin color and confirmed at 30 days gestational age (dG) (full term in this species is 180 dG) by ultrasonography. The first cohort of pregnant baboons (n = 8) were assigned to the control group and established the food consumption per kilogram of body weight on a daily basis from 30 to 90 dG.

Subsequently, the nutrient restriction (NR) group consisted of six pregnant animals who received 70% of the average daily amount of feed eaten (on a weight adjusted basis) by the eight animals fed ad libitum at the same gestational age.

2.1.4. Morphometry

The techniques used for general morphometric measurements prior to entry into the study are described elsewhere [13]. Fetal morphometric measurements were undertaken immediately after cesarean section at necropsy. Biparietal diameter, length of the dorsal-ventral abdominal axis at the level of umbilicus, and ano-genital distance were assessed with the Lange skin fold caliper (Beta Technology Inc., Cambridge, MD). Fetal length was measured from the crown to the heel of the right foot.

2.1.5. Blood sampling

Following tranquilization with ketamine HCl (10 mg/kg, i.m.), a fasting femoral venous blood sample was drawn from the non-pregnant female baboons at the time of the pre-pregnancy morphometric measurement. The inguinal site was clipped and prepared using 70% alcohol. A Precision Glide Vacutainer System (20–22 gauge needle, holder and blood tubes from Becton Dickinson Vacutainer Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was used, allowing multiple samples to be taken. One sample was drawn into a 3-mL potassium-EDTA tube (BD Vacutainer) for hematology, and another sample into a clot tube (BD Vacutainer without additives or gel separator) for assessment of serum chemistries and endocrinology. The total volume of blood taken from each animal did not exceed 15 mL. Serum and plasma were separated by centrifugation at 10,000 × g over 10 min at 4 °C, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

2.1.6. Cesarean sections

Cesarean sections were performed at 90 dG (n = 14) using standard techniques that have been previously described in detail [14]. Briefly, mothers were given ketamine HCl (10 mg/kg, i.m.) as described above. After intubation under isoflurane (4%, 2 L/min) administered by face mask, isoflurane (2%, 2 L/min) was used to maintain a surgical plane of anesthesia throughout surgery and umbilical cord blood sampling. Following hysterotomy, the umbilical cord was identified and elevated to the surgical opening for blood sampling. The fetus was euthanized by exsanguination while still under general anesthesia. The placenta was removed from the uterus and immediately submitted, together with fetus, for measurements, complete pathologic evaluation, and sampling. The uterus and abdominal wall were closed in layers. Post-operative analgesia was provided for 3 days (buprenorphine HCl, 0.015 mg/kg per day; Buprenex® Injectable, Reckitt Benckiser Health Care Ltd., Hull, UK). Ampicillin (25 mg/kg, i.m., BID) was given postoperatively for 7 days. Post-surgical management has been described in detail [14]. Animals recovered in an individual cage and were usually sitting in less than 2 h. They were observed daily until recovery by an experienced technician. Animals were released to gang cages if incisions were well healed after 2 weeks. For at least 3 months after cesarean section, females were housed with a vasectomized male to ensure that the incision was fully healed occurs before the animal became pregnant again.

2.2. Measurements of total IGF-I, total IGF-II, total IGFBP-3, free IGF-I, total IGFBP-1, growth hormone (GH), prolactin (PRL), estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4)

Growth factor and hormone levels (IGF-I, IGFBP-3, GH, PRL, E2 and P4) in baboon serum were measured on an Immulite 2000 instrument using human kits (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA), after validating their applicability for baboon serum by demonstration of parallelism. In addition, five pooled serum samples from this study were measured in at least triplicate, both within the same assay [to give intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) of less than 8.5%] and in separate assays [to provide inter-assay CV less than 11.7%] for all assays. When levels were out of range, samples were diluted with the assay buffer provided with the kits and measured again. Total IGF-II, total IGFBP-1, and free IGF-I concentrations in maternal serum and amniotic fluid were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Inc., Webster, TX). This free IGF-I assay uses ethanol extraction to eliminate the IGF bound to IGFBPs. All kits were based on human protein. The cross-reactivities between the IGF-I and IGF-II assays and among the spe-cific IGFBP ELISAs were less than 3%. Samples were measured in duplicate. Intra-assay CV was below 7%, and inter-assay CV was below 7.9%.

2.3. Hematology

Hematological data were obtained from a Coulter MAXM autoloader instrument (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA) as previously described [15]. EDTA blood smears were prepared and stained with a modified Wright stain (Accustain, Sigma Diagnostics, St. Louis, MO) and reviewed manually. The following parameters were measured automatically: white blood cell (WBC) and red blood cell (RBC) counts, hemoglobin concentration, hemato-crit, mean cell volume (MCV), mean cell hemoglobin (MCH), mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), RBC distribution width (RDW), platelet count, mean platelet volume (MPV), and differential counts of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils. Samples were stored at 22 °C and analyzed within 1 h of collection. When necessary, data for WBC counts were reviewed manually to correct for nucleated red blood cells (NRBC).

2.4. Blood chemistry

We assessed circulating levels of glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, total protein, albumin, globulin, albumin/globulin ratio (A/G ratio), cholesterol, serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT), alkaline phosphatase, sodium, potassium, chloride, carbon dioxide, and anion gap. Blood for serum analysis was collected without anticoagulant. Clotted blood was centrifuged within 1 h of collection and the serum removed. Hemolyzed samples were not evaluated. Blood biochemistry was performed using a Beckman Synchron CX5CE (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA) [15].

2.5. In situ hybridization of IGF-I, IGF-II, IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-3

Placental paraffin sections (5 μm thick) from control and maternal NR groups were analyzed for IGF-I, IGF-II, IGFBP-1, and IGFBP-3 mRNA expression by in situ hybridization using 35S-labelled antisense riboprobes as described elsewhere [16]. Briefly, tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and treated with proteinase-K. Following prehybridization, tissue sections were hybridized overnight at 42 °C–45 °C with 35S-labelled anti-sense riboprobes specific for each probe. Excess probe was washed and the tissue sections were treated with RNAse to cleave unhybridized probe. Tissue sections then underwent washes in decreasing salt buffers (1.0× SSC to 0.1× SSC) at specific temperatures for each probe. Following dehydration, slides were exposed to X-ray film overnight at −80 °C to determine the signal intensity that provided guidance for the length of exposure of the nuclear track emulsion. Slides were then coated with nuclear track emulsion and exposed at 4 °C under dessicating conditions. Slides were developed, fixed, counter-stained with hematoxylin and eosin and cover-slipped under Permount® (Fisher Scientific). Tissue sections were viewed under both dark and bright fields, and appropriate photomicrographs were obtained at 20× and 40× mag-nifications using ImagePro Plus 4.5 software. Quantification was performed on one randomly chosen slide from each animal and we took six pictures at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 o’clock on the slide. Each picture covered 2,586,000 square microns. The percentage of positive staining was recorded relative to the total area interrogated. Appropriate sense control was used for each anti-sense probe.

2.6. Immunohistochemistry for IGF-I, IGF-II, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-3, IGF-1R and IGF-2R

Paraffin tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in descending grades of alcohol (100%, 70%, and 45% in water), immersed in citrate buffer (0.01 M citrate buffer, pH 6.0), and heated to boiling for 10– 15 min. After cooling for 15 min, sections were rinsed serially (7 times, 6 min each) in potassium phosphate-buffered saline (KPBS: 0.04 M K2HPO4, 0.01 M KH2PO4, 0.154 M NaCl, pH 7.4), then washed for 10 min in a solution of 1.5% H2O2/methanol and for 5 min in KPBS. Sections were placed in diluted (10%) normal serum for 20 min and covered with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. After overnight incubation, sections were rinsed in KPBS and incubated for 1 h at 22 °C with secondary antibody (1/1000 dilution)— biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (IGF-I and IGFBP-3) or anti-goat (IGF-II, IGF-2R and IGFBP-1) for polyclonal antibodies and anti-mouse IgG for monoclonal antibodies. The antibodies for IGF-2R (goat polyclonal, dilution 1:50), IGFBP-1 (goat polyclonal, dilution 1:100), and IGFBP-3 (rabbit polyclonal, dilution 1:250) were from Santa Cruz, IGF-II was from R&D (goat polyclonal, dilution 1:500), IGF-1R (mouse monoclonal, dilution 1:50) and IGF-I (rabbit polyclonal, dilution 1:50) from Lab Vision. Preabsorbed negative control was performed with each antibody.

The sections were then handled as described by the manufacturer: 0.3% solution A (avidin) with 0.3% solution B (biotin) (Vectastain ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) incubate 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride)/nickel substrate in 0.175 M sodium acetate buffer for 10–20 min and counterstained with 0.2% methyl green. After serial dehydration in 50%, 70%, 95%, and 100% ethanol and Histoclear (3 times, 2–5 min each), sections were mounted in Histomount (National Diagnostics, USA). Images were acquired digitally and analyzed with a 5.1 mega-pixel SPOT (Diagnostics Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI) color cooled CCD camera (2650 × 1920 pixels) and ImagePro Plus 4.5 software. Quantification was performed on one randomly chosen slide from each animal, and we took three pictures at 3, 6, and 9 o’clock on the slide. Each picture covered 64,900 square microns. The percentage of positive staining was recorded relative to the total area interrogated.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Hormone values were log-transformed before statistical analysis. All parameters compared between control and maternal NR treatment groups were evaluated using Student’s two-way unpaired t-test. Variables measured in non-pregnant, control-fed and maternal NR animals at 90 dG were compared using ANOVA and Dunnett’s test. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Sig-nificance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Morphometry

3.1.1. Maternal body weight during pregnancy in NR and control groups

Control mothers (n = 8) weighed 13.7 ± 0.5 kg 30 days before introducing the fertile male, 13.4 ± 0.6 kg at 30 dG, and 13.7 ± 0.4 kg at 90 dG. NR mothers (n = 6) weighed 13.0 ± 0.2 kg and 13.0 ± 0.3 and 12.2 ± 0.3 kg at the same gestational stages, respectively. The fall in maternal weight in NR mothers at 90 dG represented a 9.1% weight loss (p < 0.05).

Fetal weight in the NR group at 90 dG was 95.4 ± 3.3 g (n = 6) compared to 100.9 ± 3.4 g (n = 8) for fetuses of control mothers. This reduction in fetal weight of approximately 5% was not statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Morphometric characteristics of fetuses of mothers fed ad libitum (CTR) or fed 70% of CTR diet (NR) at 90 dGA (mean ± SEM)

| CTR n = 8 | NR n = 6 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | 100.9 ± 3.37 | 95.4 ± 3.27 | 0.276 |

| Length (cm) | 17.9 ± 0.31 | 17.5 ± 0.44 | 0.505 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 3.1 ± 0.09 | 3.1 ± 0.12 | 0.782 |

| Biparietal distance (mm) | 33.5 ± 0.48 | 34.2 ± 0.70 | 0.437 |

| Dorsal-ventral abdominal distance (mm) | 25.9 ± 3.22 | 29.2 ± 1.62 | 0.426 |

| Femur length (mm) | 35.3 ± 1.13 | 32.5 ± 1.12 | 0.117 |

| Chest circumference (mm) | 88.8 ± 2.27 | 87.9 ± 2.27 | 0.804 |

| Waist circumference (mm) | 75.5 ± 2.48 | 75.8 ± 2.71 | 0.930 |

| Hip circumference (mm) | 73.4 ± 1.70 | 68.3 ± 1.67 | 0.058 |

| Sterno-pubis distance (mm) | 67.2 ± 4.16 | 70.8 ± 0.83 | 0.471 |

| Placenta (g) | 70.4 ± 5.09 | 62.9 ± 1.48 | 0.245 |

| Fetal membranes (g) | 11.0 ± 3.06 | 7.5 ± 1.04 | 0.356 |

| Placenta diameter (cm) | 7.9 ± 0.30 | 7.3 ± 0.32 | 0.147 |

| Umbilical cord length (cm) | 14.1 ± 0.80 | 11.8 ± 0.90 | 0.089 |

| Placental efficiency | 1.5 ± 0.07 | 1.5 ± 0.06 | 0.615 |

| Brain (g) | 32.6 ± 1.75 | 30.1 ± 0.52 | 0.252 |

| Liver (g) | 3.3 ± 0.15 | 3.2 ± 0.20 | 0.687 |

| Spleen (g) | 0.6 ± 0.19 | 0.3 ± 0.04 | 0.233 |

| Kidneys (g) | 1.0 ± 0.15 | 0.8 ± 0.13 | 0.567 |

| Lung (g) | 3.5 ± 0.11 | 3.4 ± 0.14 | 0.435 |

| Heart (g) | 0.9 ± 0.27 | 0.6 ± 0.06 | 0.326 |

| Adrenals (g) | 0.4 ± 0.12 | 0.3 ± 0.10 | 0.700 |

3.2. Circulating hormone profiles in non-pregnant and pregnant baboons and effect of maternal NR

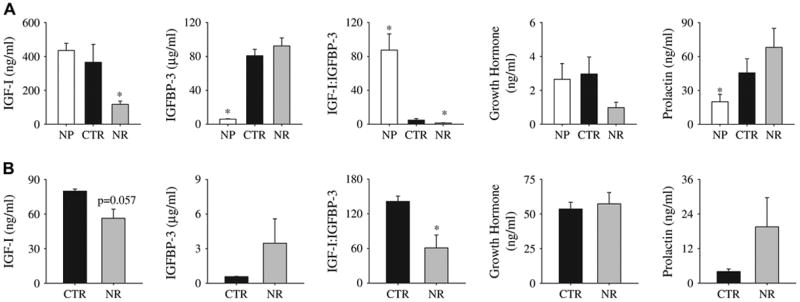

Total maternal serum IGFBP-3 level was higher in pregnant control than in non-pregnant baboons (p < 0.05), while total circulating IGF-I level was unchanged (Fig. 1A). As a result, the IGF-I:IGFBP-3 ratio was lower in pregnant than non-pregnant baboons (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A, Serum measurements in adult female baboons when non-parous (NP, n = 12), fed ad libitum (control, n = 5) at 90 dG, and when fed 70% of control (from 30 to 90 days gestation (dG)) and at 90 dG (NR, n = 6). B, Fetal serum measurements at 90 days gestation (dG) in baboons fed ad libitum (control, n = 5) and 70% of control (NR) at 90 dG from 30 to 90 dG (NR, n = 6) animals. Values are mean ± SE; SE is too small to show for the IGF-I/IGFBP-3 ratio (A). *p < 0.05 vs. control (unpaired t-test).

Maternal serum prolactin concentrations rose (p < 0.05), while serum growth hormone concentration was unchanged (Fig. 1B). Levels of fetal serum total IGF-I and total IGFBP-3 were lower than maternal levels in the control group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1B). Compared to maternal values, circulating fetal growth hormone level was higher, whereas circulating fetal prolactin level was lower (p < 0.05).

Maternal total IGF-I serum levels were lower at 90 dG after NR (p < 0.05 compared to control) (Fig. 1A). Fetal total IGF-I level was not significantly lower after NR (Fig. 1B; p = 0.06). Circulating total IGFBP-3 levels were unchanged by NR in both mother and fetus. The IGF-I:IGFBP-3 ratio was lower in serum of NR mothers and their fetuses (p < 0.05) than controls (Fig. 1). Maternal and fetal GH and prolactin levels (Fig. 1) and total IGF-II concentration in maternal serum did not differ between control and NR groups (18.7 ± 0.38 and 18.4 ± 0.62 μg/mL, respectively). Total IGF-II concentration in amniotic fluid at 90 dG was not different in NR (390.7 ± 20.61 ng/mL) and control animals (329.9 ± 31.0 ng/mL). Maternal serum IGFBP-1 concentration did not differ at 90 dG between control (130.3 ± 3.4 ng/mL) and NR groups (133.2 ± 2.8 ng/mL). The concentration of free IGF-I in maternal serum was significantly lower in NR than control animals (0.11 ± 0.01 ng/mL vs. 0.18 ± 0.02 ng/mL, p < 0.05). The maternal estradiol and progesterone concentrations in control animals (7128.75 ± 1921.47 pg/ml and 25.57 ± 4.94 ng/ml, respectively were essentially the same as in NR group (6649.67 ± 2805.2 pg/ml and 36.34 ± 18.5 ng/ml subsequently).

3.3. Circulating metabolic and hematologic variables in pregnant baboons after NR

The only change observed in basic hematologic variables was a small but significant rise in fetal mean cell hemoglobin concentration resulting from NR (Table 2). There was no change in maternal or fetal glucose, and the fetal:maternal glucose ratio was similar (0.66 ± 0.07 in NR pregnancies vs. 0.47 ± 0.07 in CTR pregnancies; p = 0.06). In NR mothers and their fetuses, serum BUN decreased (p < 0.01 vs. control). NR lowered the ratio of BUN to creatinine and lowered the concentration of alkaline phosphatase in fetal serum (p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hematologic and clinical chemistry values in control vs. maternal nutrient restricted (NR) baboons at 90 dG (values are mean± SEM)

| Fetus

|

Mother

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 5–7) | NR (= 3–6) | Control (n = 8) | NR (n = 6) | |

| Hematology | ||||

| WBC (×109/L) | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 11.0 ± 1.1 | 9.1 ± 0.7 |

| RBC (×1012/L) | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.1 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.1 ± 0.2 | 11.8 ± 0.1 | 12.6 ± 0.3 | 12.9 ± 0.4 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 34.6 ± 0.6 | 36.3 ± 0.6 | 37.9 ± 1.3 | 38.6 ± 1.1 |

| MCV (fL) | 128.2 ± 1.4 | 132.6 ± 1.4 | 78.7 ± 1.0 | 77.9 ± 0.6 |

| MCH (pg) | 41.0 ± 0.3 | 42.8 ± 0.7a | 26.2 ± 0.3 | 26.0 ± 0.4 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 32.0 ± 0.2 | 32.3 ± 0.3 | 33.3 ± 0.3 | 33.4 ± 0.4 |

| RDW (%) | 17.0 ± 0.3 | 17.6 ± 0.5 | 11.5 ± 0.2 | 11.1 ± 0.2 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 381.0 ± 19.7 | 387.3 ± 19.6 | 231.8 ± 22.0 | 257.7 ± 31.3 |

| MPV (fL) | 8.3 ± 0.4 | 8.6 ± 0.4 | 9.5 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.4 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 9.0 ± 4.1 | 4.7 ± 2.7 | 58.1 ± 3.9 | 56.2 ± 6.1 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 89.8 ± 4.2 | 94.7 ± 2.4 | 36.5 ± 3.2 | 37.3 ± 8.0 |

| Monocyte (%) | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.6 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

| Basophil (%) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| Clinical Chemistry | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 47.1 ± 4.4 | 39.0 ± 7.4 | 74.4 ± 9.6 | 85.8 ± 10.6 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 11.0 ± 0.6 | 8.0 ± 0.5a | 10.3 ± 0.7 | 7.5 ± 0.4a |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.0 | 6.7 ± 0.2 | 6.7 ± 0.2 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.8 ± 0.0 | 1.9 3 0.0 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.1 |

| Globulin (calc) (g/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.1 |

| A/G ratio (calc) | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.0 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 65.6 ± 4.1 | 58.5 ± 3.4 | 51.6 ± 5.6 | 42.2 ± 1.7 |

| Triglycerides(mg/dL) | 36.4 ± 4.9 | 28.8 ± 5.5 | 28.9 ± 3.4 | 30.0 ± 6.1 |

| Alkaline phosphatase(mg/dL) | 116.8 ± 4.4 | 126.5 ± 11.6 | 460.3 ± 37.2 | 346.5 ± 33.3a |

p < 0.05 vs. control by two-sided test.

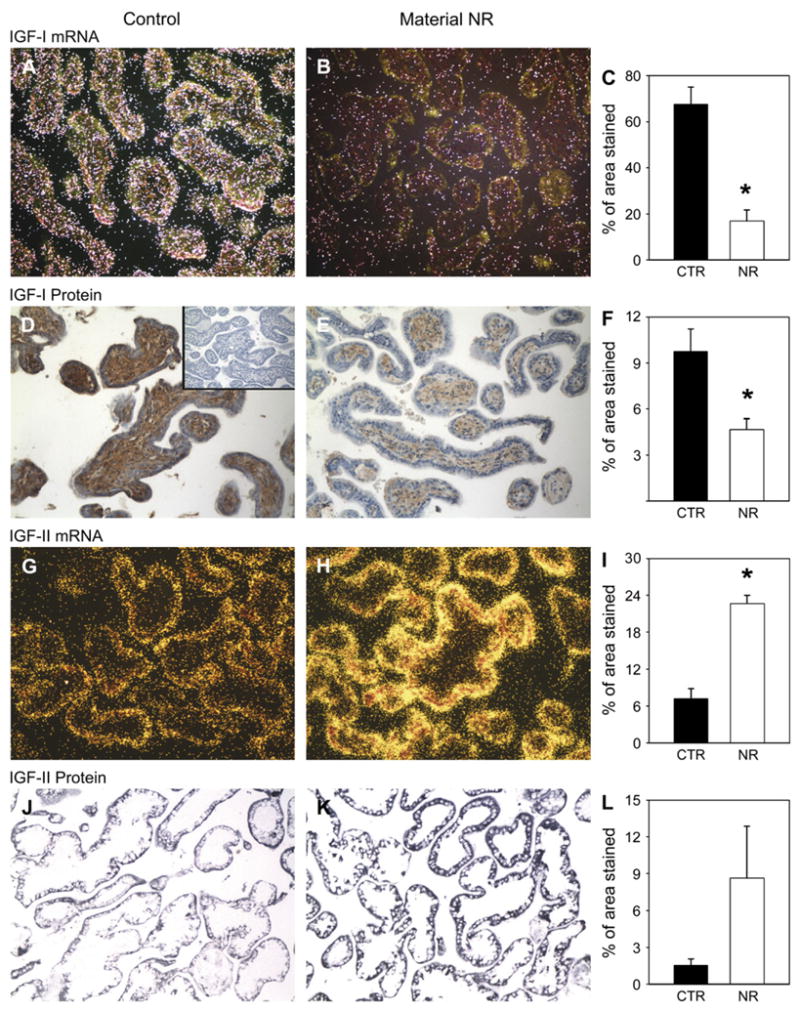

3.4. IGF-I and IGF-II gene and protein localization and abundance in the placenta by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

IGF-I mRNA was expressed in both the syncytiotrophoblast and villous core (Figs. 2A,B), while protein expression was observed mostly in the villous core (Figs. 2D,E). Both mRNA expression and protein abundance were reduced to a similar extent in placental tissue of NR animals (Figs. 2C,F). Both IGF-II protein and mRNA expression were localized in the syncytiotrophoblast (Figs. 2G,H,J,K). The level of mRNA was increased by NR (p < 0.05) (Figs. 2I,L).

Fig. 2.

IGF-I gene (in situ hybridization, first row) and protein (immunohistochemistry, second row) expression in placentae from control (A and D; n = 6) and 30% maternal NR (B and E; n = 6) groups at 90 dG. Inset (D), Negative control. Quantification for all animals (C and F). IGF-II expression (in situ hybridization, third row) and protein location (immunohistochemistry, fourth row) in placentae from control (G and J; n = 6) and 30% maternal NR (H and K; n = 6) groups at 90 dG. Quantification for all animals (I and L). *p < 0.05 vs. control. Magnification 20×.

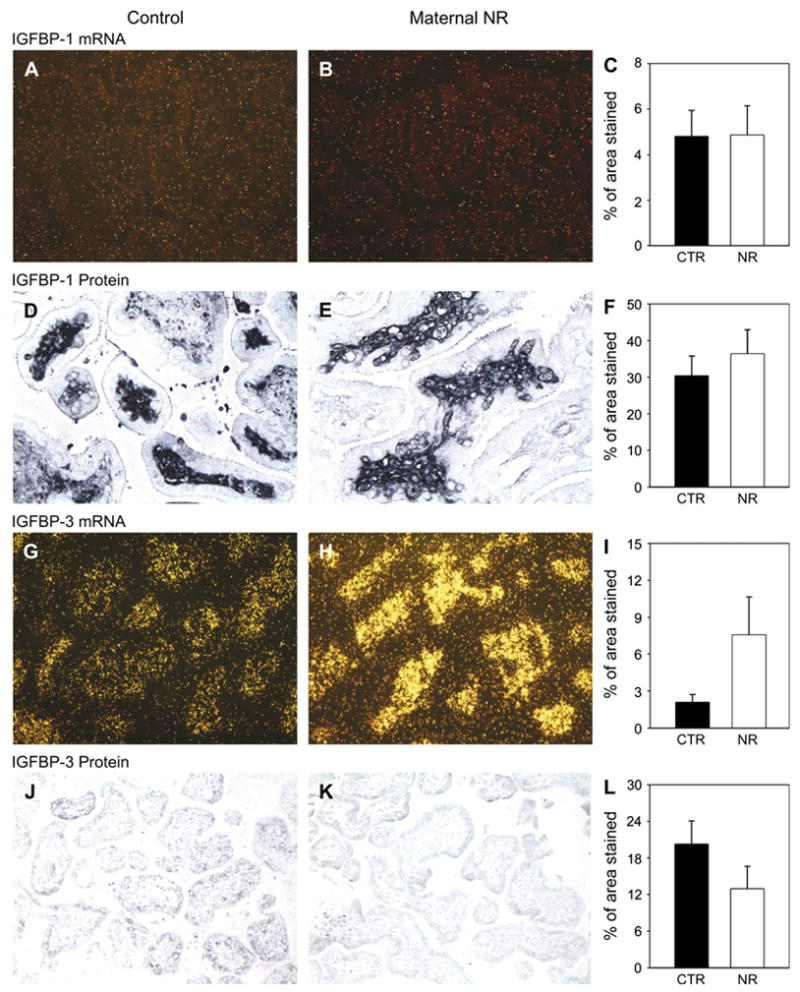

3.5. IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-3 gene and protein localization and abundance the placenta by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

IGFBP-1mRNAwaslocalizedinvillouscorewithalowlevelof expression, whichwas not changedby maternal NR (Figs.3A–C). Protein expression of IGFBP-1 was detected in the villous core of both control and maternal NR placentas (Figs. 3D,E). IGFBP-3 mRNA was expressed in the villous core, and IGFBP-3 protein was observed in the syncytiotrophoblast (Figs. 3G,H) but did not increase significantly with NR (Figs. 3I,L).

Fig. 3.

IGFBP-1 expression (in situ hybridization, first row) and protein location (immunohistochemistry, second row) in placentae from control (A and D; n = 6) and 30% maternal NR (B and E; n = 6) groups at 90 dG. Quantification for all animals (C and F). IGFBP-3 expression (in situ hybridization, third row) and protein location (immunohistochemistry, fourth row) in placentae from control (G and J; n = 6) and 30% maternal NR (H and K; n = 6) groups at 90 dG. Quantification for all animals (I and L). *p < 0.05 vs. control. Magnification 20× (A, B, G, H, J, K) and 40×(D and E).

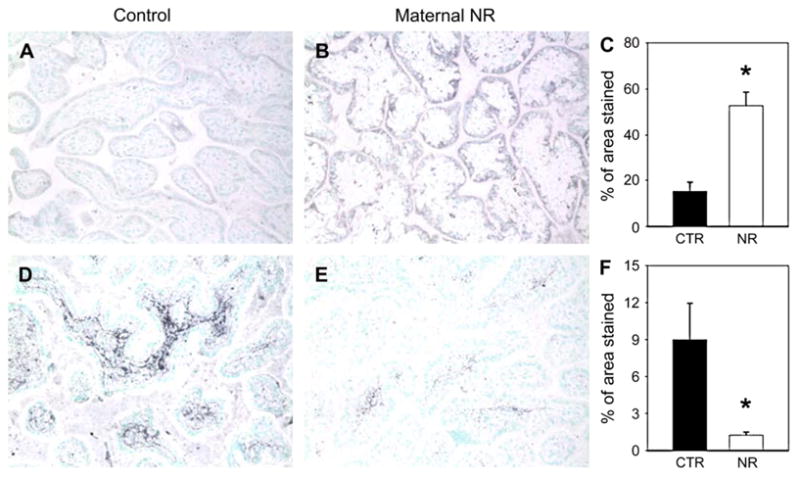

3.6. Placental IGF receptors by immunohistochemistry

IGF-1R protein abundance was observed in syncytiotropho-blasts and increased in the placentae of the NR group (Figs. 4A–C). IGF-2R was expressed in the core of stem villi, and its abundance decreased in placentae from the NR group (Figs. 4D–F).

Fig. 4.

IGF1R (first row) and IGF2R (second row) immunohistochemistry in placentae from control (n = 6) and 30% maternal NR (n = 6) groups at 90 dG. Quan-tification for all animals (C and F). *p < 0.05 vs. control. Magnification 20×.

4. Discussion

Endocrine and metabolic regulation of fetal growth and development differs greatly from postnatal regulation (reviewed in ref. [7]). Global NR during pregnancy at levels similar to that in our study [17,18], and even more extreme restriction [19], has been extensively studied in sheep, pigs, and rats [17–20]. The IGF system within the placenta and several fetal organs has been shown to respond to both global and other forms of NR during pregnancy. However, to our knowledge this is the first report of data on the IGF system in the placenta in response to maternal NR of any form in a non-human primate.

4.1. Systemic changes in IGF system

4.1.1. Changes between the non-pregnant and pregnant state

We observed no change in circulating maternal total IGF-I level comparing non-parous females with females at the end of the first half of pregnancy, which is consistent with other reports in non-human primates [21] and women [22]. Circulating total IGF-I concentration has been shown to peak after week 35 of gestation in pregnant women [22]. Confirming published data for human gestation [23], serum GH levels did not differ between non-pregnant and pregnant baboons by mid-gestation in our study. During late gestation, maternal serum concentrations of total IGF-II are 3- to 10-fold higher than IGF-I in all species studied to date, including monkey [24]. Our study confirmed these observations.

4.1.2. Maternal and fetal growth

Maternal weight gain during the first trimester in pregnant women strongly predicts subsequent fetal growth [25]. By 90 dG, NR maternal baboons had lost 9.1% total body weight. However there was no significant difference in fetal weights between control and maternal NR groups. Various NR protocols in other animal species have yielded variable outcomes for fetal organ and total body weights. In sheep, mild and moderate maternal NR (30–50%) during early gestation (the period of maximal placental growth and the time comparable to the maternal NR period in our study) induced no decrease in fetal body weight, consistent with our findings [26]. As in our study, Osgerby et al. [27] detected no differences in placental weight when ewes were exposed to 30% maternal NR during the first half of gestation. Overall, fetal growth is a very poor measure of altered fetal organ development and it is now clear that considerable functional and structural changes can take place in the placenta and fetal organs in the absence of any gross weight change. We have shown that this degree of MNR significantly affects fetal renal [28] (e.g., mTOR related gene expression) and placental (placental villous tree) development [29] at 90 dG in the absence of an overall change in fetal kidney or placental weights.

We observed a fall in fetal:maternal glucose ratio that almost reached significance and may reflect decreased placental glucose transfer. BUN and BUN:creatinine ratio were decreased, consistent with decreased protein turnover and growth. Lower alkaline phosphatase levels in fetal blood after maternal NR would be expected to reflect decreased fetal osteoblast function, a problem that could eventually lead to in-trauterine growth restriction. We would anticipate greater differences if the maternal NR were carried forward into the later phases of gestation when greater fetal growth occurs.

4.1.3. Normal profiles of circulating components of the baboon IGF-IGFBP axis

The IGF-IGFBP axis is a major regulator of fetal growth and metabolic activity. For example, exogenous IGF-I administered to the pregnant guinea pigs increases fetal and placental weights [30]. Maternal serum total IGF-I levels at 90 dG (the middle of the normal 180-day gestation) in our pregnant baboons were comparable to data reported by Putney et al. [21] for pregnant baboons at 100 dG and for pregnant humans before 35 weeks of gestation [22]. During late gestation, maternal serum concentrations of total IGF-II are 3- to 10-fold higher than IGF-I in all species studied to date: monkey, rats, cattle, pigs, guinea pigs, and sheep. Our study confirmed these observations.

4.1.4. Effects of maternal NR on the maternal and fetal IGF-IGFBP axes

The effects on circulating total IGF-I levels from diverse maternal NR paradigms have been reported for several animal models. The observed decreases in circulating total IGF-I level and IGF-I:IGFBP-3 ratio for both mother and fetus in the presence of moderate maternal NR are consistent with other mammalian studies. In response to 60% global diet restriction in sheep pregnancy, Bispham et al. [17] observed lower maternal total and free IGF-I levels and normal maternal glucose, consistent with our findings in the baboon. IGFBPs stabilize the IGF-I level across the 24-h period. This stability and the exquisite responsiveness of total IGF-I release to nutrient delivery make the free IGF-I level in serum a sensitive marker of nutritional status [31]. Dietary restriction can decrease hepatic IGFBP secretion into the peripheral circulation, thereby increasing the clearance and degradation of circulating IGFs. The change in IGF-I:IGFBP-3 ratio we observed in both fetus and mother likely reflects decreased bioavailability of free IGF-I to fetal and maternal tissues. Shown here for the first time in a non-human primate model, these disturbances are accompanied by evidence of decreased protein metabolism. Although growth hormone is a powerful regulator of prenatal IGF synthesis, fetal IGF-I production is primarily regulated by glucose (nutrient) availability to the fetus [32]. In sheep, maternal NR has also been shown to reduce fetal growth hormone production [33].

Putney et al. [21] suggested the baboon placenta does not contribute significantly to the circulating maternal IGF-I pool during pregnancy. The liver is the major site of IGF-I synthesis in mammalian adults [34,35], and hepatic production of IGF-I is sufficient to maintain the relatively large amount of IGF-I in the peripheral circulation (at least 50% of total body content) [35]. We observed that 30% maternal NR (fed 70% of food consumed by control animals) was associated with decreased free IGF-I and lower total IGF-I:IGFBP-3 ratio in the fetal circulation. We have also noted a marked fall in hepatic IGF-I mRNA and protein in this model (unpublished observations).

4.2. Changes in the placental IGF system

4.2.1. IGF-I and IGF-II

Maternal IGF-I promotes fetal growth by stimulating nutrient transport in the placenta, influencing placental blood flow and placental function. Maternal IGF-I in its bound form does not cross the placental barrier in rats; however, the placenta transports free IGF [36]. IGF-I gene expression is high in the human placenta at term, but the corresponding protein is undetectable [37,38]. In agreement with data published by Carter and Han, IGF-I mRNA expression in our study was detected in syncytiotrophoblast [5]. However, the greatest protein expression was observed in the villous core. This interesting discrepancy may reflect transport of the protein from its site of synthesis. While mRNA localization mirrors IGF-I synthesis, protein distribution reflects both synthesis and transport to active sites. The presence of IGF-I in the villous core might mirror the involvement of this molecule in the process of vascularization and angiogenesis.

One of the major roles of IGF-II is placental formation and remodeling. IGF-II is produced by the invasive extravil-lous trophoblast (EVT) in baboons and humans [39–41] and by decidua and trophoblast in guinea pigs [42]. In our study, both IGF-II mRNA and protein expression were detected in syncytiotrophoblast and cytotrophoblast with increased expression in placentae of the NR group. Our data are in agreement with observation of Zollers et al., who found IGF-II mRNA expression in baboon syncytiotrophoblast [6]. Increased placental expression of IGF-II has been detected with IUGR [43]. It is important to note that the placenta discriminates between IGF-II produced within the organ and that produced by the fetus [44]. In our study, the increase in IGF-II mRNA expression clearly indicates increased IGF-II synthesis. Unchanged total IGF-II in the maternal circulation under NR conditions has also been reported in sheep and may indicate that IGF-II abundance is less regulated by nutritional changes in pregnancy than IGF-I.

4.3. IGFBP-1 and IGFBP-3

IGFBP-1 in humans is produced mostly by the decidua at least in early pregnancy, and is thought to play a role in regulating trophoblast invasion [45,46]. Regulation and function of placental IGFBP-1 differs from species to species. For example, guinea pig and murine decidua do not normally express IGFBP-1 [47,48], and sheep have non-deciduate placentae in which IGFBP-3 exerts paracrine-autocrine regulation [49]. These differences have overt consequences. IUGR in humans (but not in guinea pigs, sheep, and rats) is associated with elevated placental IGFBP-1 level. Mice over-expressing placental IGFBP-1 via the AFP promotor demonstrate increased placental weight (150% of wild-type) at e16.5 [50].

IGFBP-3 proteolysis is one of the major regulators of IGF availability in pregnancy serum. IGF-I-independent mechanisms of action of IGFBP-3 are complex, predominantly intra-cellular, and result in apoptosis or insulin resistance. In the human placenta, IGFBP-3 localizes immunohistochemically in the syncytium and is considered to be involved in the apo-ptotic process of pre-eclampsia [51]. We observed a similar location of IGFBP-3 protein in the present study.

4.4. IGF receptors

Our observation of IGF-1R location in the syncytiotropho-blast of placenta parallels data from human pregnancies [52]. Increased IGF-1R protein expression in our study contradicts data published for human IUGR [53]. Our data do agree with findings of Abu-Amero et al. [43] who reported that with IUGR the term placentae displayed higher levels of IGF2 and IGF1R expression compared with the normal term placentae. These changes would increase the local activity of IGF-I and IGF-II, which may be compensating to maintain placental growth in the presence of decreased nutrient availability.

In conclusion, our data indicate that even moderate global dietary restriction—that is, food consumption of 70% of that consumed by ad libitum fed animals—significantly disrupts the circulating maternal and fetal IGF-IGFBP axis and influ-ences placental expression of components of this key system at the gene and protein levels. Normal placental function is critical to fetal maturation. Changes in the IGF-IGFBP system in this non-human primate model appear to be directed toward promoting the local growth of the placenta, which is critical to fetal growth and development.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NIH grant K08 DK02876 (to R.F.), the SPC Russell H. Nahvi Memorial Fund for Pediatric Research at UTHSCSA, and NIH-NCRR grant P51 RR013986 to the Southwest National Primate Research Center. The opinions herein are solely those of the authors and do not represent an official position of The State of Texas, the United States Army, or their subordinate agencies. The authors thank Mrs. Xiaojing Xu for her assistance with IGF-II, free IGF-I and IGFBP-1 ELISAs, Mrs. Karen Nygard for her excellent work on in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry and Mrs. Myrna Miller for performance of estradiol and progesterone assays.

References

- 1.Bajoria R, Sooranna SR, Ward S, Hancock M. Placenta as a link between amino acids, insulin-IGF axis, and low birth weight: evidence from twin studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:308–15. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.1.8184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding JE, Liu L, Evans PC, Gluckman PD. Insulin-like growth factor 1 alters feto-placental protein and carbohydrate metabolism in fetal sheep. Endocrinology. 1994;134:1509–14. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.3.8119193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller AG, Aplin JD, Westwood M. Adenovirally mediated expression of insulin-like growth factors enhances the function of first trimester placental fibroblasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:379–85. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jansson T, Powell TL. Award in Placentology Lecture. Human placental transport in altered fetal growth: does the placenta function as a nutrient sensor? Placenta. 2006;27(Suppl A):S91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.11.010. Epub 2006 Jan 25 IFPA 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han VK, Carter AM. Spatial and temporal patterns of expression of messenger RNA for insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in the placenta of man and laboratory animals. Placenta. 2000;21:289–305. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zollers WG, Babischkin JS, Pepe GJ, Albrecht ED. Developmental regulation of placental insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-II and IGF-binding protein-1 and -2 messenger RNA expression during primate pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:1208–14. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.4.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroder HJ. Comparative aspects of placental exchange functions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;63:81–90. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02206-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nayak NR, Giudice LC. Comparative biology of the IGF system in endometrium, decidua, and placenta, and clinical implications for foetal growth and implantation disorders. Placenta. 2003;24:281–96. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoknecht PA, Pond WG, Mersmann HJ, Maurer RR. Protein restriction during pregnancy affects postnatal growth in swine progeny. J Nutr. 1993;123:1818–25. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riopelle AJ, Hill CW, Li SC, Wolf RH, Seibold HR, Smith JL. Protein deficiency in primates. IV. Pregnant rhesus monkey. Am J Clin Nutr. 1975;28:20–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/28.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis RM, Petry CJ, Ozanne SE, Hales CN. Effects of maternal iron restriction in the rat on blood pressure, glucose tolerance, and serum lipids in the 3-month-old offspring. Metabolism. 2001;50:562–7. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.22516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Howell K, Rice K, Glover JE, Nevill HC, Jenkins SL, et al. Development of a system for individual feeding of baboons maintained in an outdoor group social environment. J Med Prima-tol. 2004;33:117–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Dudley CJ, Gomez JJ, Nevill CH, Smith BK, Jenkins SL, et al. Metabolic adjustments to moderate maternal nutrient restriction. Br J Nutr. 2007 Mar 29;:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507700727. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, Dammann MJ, Jenkins SL, Frost PA, McDonald TJ, et al. Normal concentrations of essential and toxic elements in pregnant baboons and fetuses (Papio species) J Med Primatol. 2004;33:152–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, Jenkins SL, Martin HC, Snider CS, Frost PA, et al. Ontogeny of hematological cell and biochemical profiles in the maternal and fetal baboon (Papio species) J Med Pri-matol. 2005;34:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2005.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han VKM, Bassett N, Walton J, Challis JRG. The expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and IGF binding protein (IGFBP) genes in the human placenta and membranes: evidence for IGF-IGFBP interactions at the feto-maternal interface. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1996;81:2680–93. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.7.8675597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bispham J, Gopalakrishnan GS, Dandrea J, Wilson V, Budge H, Keisler DH, et al. Maternal endocrine adaptation throughout pregnancy to nutritional manipulation: consequences for maternal plasma leptin and cortisol and the programming of fetal adipose tissue development. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3575–85. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozaki T, Nishina H, Hanson MA, Poston L. Dietary restriction in pregnant rats causes gender-related hypertension and vascular dysfunction in offspring. J Physiol. 2001;530:141–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0141m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu MJ, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Du M. Effect of maternal nutrient restriction in sheep on the development of fetal skeletal muscle. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:1968–73. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.034561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rehfeldt C, Nissen PM, Kuhn G, Vestergaard M, Ender K, Oksbjerg N. Effects of maternal nutrition and porcine growth hormone (pGH) treatment during gestation on endocrine and metabolic factors in sows, fetuses and pigs, skeletal muscle development, and postnatal growth. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2004;27:267–85. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Putney DJ, Pepe GJ, Albrecht ED. Influence of the fetus and estrogen on serum concentrations and placental formation of insulin-like growth factor I during baboon pregnancy. Endocrinology. 1990;127:2400–7. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-5-2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chellakooty M, Vangsgaard K, Larsen T, Scheike T, Falck-Larsen J, Legarth J, et al. A longitudinal study of intrauterine growth and the placental growth hormone (GH)-insulin-like growth factor I axis in maternal circulation: association between placental GH and fetal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:384–91. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alsat E, Guibourdenche J, Couturier A, Evain-Brion D. Physiological role of human placental growth hormone. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;140:121–7. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarantal AF, Gargosky SE. Characterization of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) axis in the serum of maternal and fetal macaques (Macaca mulatta and Macaca fascicularis) Growth Regul. 1995;5:190–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown JE, Murtaugh MA, Jacobs DR, Jr, Margellos HC. Variation in newborn size according to pregnancy weight change by trimester. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:205–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heasman L, Clarke L, Stephenson TJ, Symonds ME. The influence of maternal nutrient restriction in early to mid-pregnancy on placental and fetal development in sheep. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58:283–8. doi: 10.1017/s0029665199000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osgerby JC, Wathes DC, Howard D, Gadd TS. The effect of maternal undernutrition on the placental growth trajectory and the uterine insulin-like growth factor axis in the pregnant ewe. J Endocrinol. 2004;182:89–103. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1820089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox LA, Nijland MJ, Gilbert JS, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, McDonald TJ, et al. Effect of 30 per cent maternal nutrient restriction from 0.16 to 0.5 gestation on fetal baboon kidney gene expression. J Physiol. 2006;572(Pt 1):67–85. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, Ballesteros B, Dudley C, Jenkins S, Hubbard G, Burton GJ, et al. Moderate maternal nutrient restriction, but not glucocorticoid administration, leads to placental morphological changes in the baboon (Papio sp.) Placenta. 2007 Mar 22; doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.11.012. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sohlstrom A, Fernberg P, Owens JA, Owens PC. Maternal nutrition affects the ability of treatment with IGF-I and IGF-II to increase growth of the placenta and fetus, in guinea pigs. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2001;11:392–8. doi: 10.1054/ghir.2001.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harding JE. Nutrition and growth before birth. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2003;12(Suppl):S28. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gluckman PD, Harding JE. The physiology and pathophysiology of in-trauterine growth retardation. Horm Res. 1997;48(Suppl 1):11–6. doi: 10.1159/000191257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bauer MK, Breier BH, Harding JE, Veldhuis JD, Gluckman PD. The fetal somatotropic axis during long term maternal undernutrition in sheep: evidence for nutritional regulation in utero. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1250–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.3.7867579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Ercole AJ, Stiles AD, Underwood LE. Tissue concentrations of so-matomedin C: further evidence for multiple sites of synthesis and para-crine or autocrine mechanisms of action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:935–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwander JC, Hauri C, Zapf J, Froesch ER. Synthesis and secretion of insulin-like growth factor and its binding protein by the perfused rat liver: dependence on growth hormone status. Endocrinology. 1983;113:297–305. doi: 10.1210/endo-113-1-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davenport ML, Pucilowska J, Clemmons DR, Lundblad R, Spencer JA, Underwood LE. Tissue-specific expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 protease activity during rat pregnancy. Endocrinology. 1992;130:2505–12. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.5.1374007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laviola L, Perrini S, Belsanti G, Natalicchio A, Montrone C, Leonardini A, et al. Intrauterine growth restriction in humans is associated with abnormalities in placental insulin-like growth factor signaling. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1498–505. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Street ME, Seghini P, Fieni S, Ziveri MA, Volta C, Martorana D, et al. Changes in interleukin-6 and IGF system and their relationships in placenta and cord blood in newborns with fetal growth restriction compared with controls. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:567–74. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohlsson R, Holmgren L, Glaser A, Szpecht A, Pfeifer-Ohlsson S. Insulin-like growth factor 2 and short-range stimulatory loops in control of human placental growth. EMBO J. 1989;8:1993–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jasinska A, Han V, Fazleabas AT, Kim JJ. Induction of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 expression in baboon endometrial stromal cells by cells of trophoblast origin. Reprod Sci. 2004;11:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamilton GS, Lysiak JJ, Han VK, Lala PK. Autocrine-paracrine regulation of human trophoblast invasiveness by insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-II and IGF-binding protein (IGFBP)-1. Exp Cell Res. 1998;244:147–56. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han VK, Carter AM, Chandarana S, Tanswell B, Thompson K. Ontogeny of expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and IGF binding protein mRNAs in the guinea-pig placenta and uterus. Placenta. 1999;20:361–77. doi: 10.1053/plac.1998.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abu-Amero SN, Ali Z, Bennett P, Vaughan JI, Moore GE. Expression of the insulin-like growth factors and their receptors in term placentas: a comparison between normal and IUGR births. Mol Reprod Dev. 1998;49:229–35. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199803)49:3<229::AID-MRD2>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Constância M, Angiolini E, Sandovici I, Smith P, Smith R, Kelsey G, et al. Adaptation of nutrient supply to fetal demand in the mouse involves interaction between the Igf2 gene and placental transporter systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:19219–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504468103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hustin J, Philippe E, Teisner B, Grudzinskas JG. Immunohistochemical localization of two endometrial proteins in the early days of human pregnancy. Placenta. 1994;15:701–8. doi: 10.1016/0143-4004(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han VK, Bassett N, Walton J, Challis JR. The expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and IGF-binding protein (IGFBP) genes in the human placenta and membranes: evidence for IGF-IGFBP interactions at the feto-maternal interface. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2680–93. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.7.8675597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giudice LC. Maternal-fetal conflict-lesions from a transgene. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:307–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI16389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carter AM, Kingston MJ, Han KK, Mazzuca DM, Nygard K, Han VK. Altered expression of IGFs and IGF-binding proteins during intrauterine growth restriction in guinea pigs. J Endocrinol. 2005;184:179–89. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wathes DC, Reynolds TS, Robinson RS, Stevenson KR. Role of the insulin-like growth factor system in uterine function and placental development in ruminants. J Dairy Sci. 1998;81:1778–89. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75747-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watson CS, Bialek P, Anzo M, Khosravi J, Yee SP, Han VK. Elevated circulating insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 is sufficient to cause fetal growth restriction. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1175–86. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han JY, Kim YS, Cho GJ, Roh GS, Kim HJ, Choi WJ, et al. Altered gene expression of caspase-10, death receptor-3 and IGFBP-3 in preeclamptic placentas. Mol Cells. 2006;22:168–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fang J, Furesz TC, Lurent RS, Smith CH, Fant ME. Spatial polarization of insulin-like growth factor receptors on the human syncytiotrophoblast. Pediatr Res. 1997;41:258–65. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199702000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holmes R, Porter H, Newcomb P, Holly JMP, Soothill P. An immuno-histochemical study of type I insulin-like growth factor receptors in the placentae of pregnancies with appropriately grown or growth restricted fetuses. Placenta. 1999;20:325–30. doi: 10.1053/plac.1998.0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]