Abstract

Background

Phenotypically, the aortic valve interstitial cell (AVIC) is a dynamic myofibroblast, appearing contractile and activated in times of development, disease, and remodeling. The precise mechanism of phenotypic modulation is unclear, but it is speculated that both biomechanical and biochemical factors are influential. Therefore, we hypothesized that isolated and combined treatments of cyclic tension and TGF-β1 would alter the phenotype and subsequent collagen biosynthesis of AVICs in situ.

Methods and Results

Porcine aortic valve leaflets received 7 and 14 day treatments of 15% cyclic stretch (Tension), 0.5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (TGF), 15% cyclic stretch and 0.5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (Tension+TGF), or neither mechanical nor cytokine stimuli (Null). Tissues were homogenized and assayed for AVIC phenotype (smooth muscle α-actin (SMA)) and collagen biosynthesis (via heat shock protein 47 (Hsp47) which was further verified with type I collagen C-terminal propeptide (CICP)). At both 7 and 14 days, SMA, Hsp47, and CICP quantities were significantly greater (p<0.001) in the Tension+TGF group compared to all other groups. Additionally, Tension alone appeared to maintain SMA and Hsp47 levels that were measured at day 0, while TGF alone elicited an increase in SMA and Hsp47 compared to day 0 levels. Null treatment revealed diminished proteins at both time points.

Conclusions

Elevated TGF-β1 levels, in the presence of cyclic mechanical tension, resulted in synergistic increases in the contractile and biosynthetic proteins in AVICs. Since cyclic mechanical stimuli can never be relieved in vivo, the presence of TGF-β1 (possibly from infiltrating macrophages) may result in overly biosynthetic AVICs, leading to altered ECM architecture, compromised valve function, and ultimately degenerative valvular disease.

Keywords: Aortic valve interstitial cells, degenerative valve disease, TGF-β1, heart valve remodeling, myofibroblasts

INTRODUCTION

Aortic valve leaflets (AVLs) are unique tissues that are both supple and strong, allowing them to perform their primary function of unidirectional blood flow. Their suppleness is required for efficient opening and closing, while their compliance and strength permit apposition to withstand blood-imposed transvalvular pressure when the valve is closed. The ability to perform these passive responses is severely compromised by degenerative disease conditions wherein the leaflets become either calcified and/or fibrotic. Both conditions result in stiffening of the leaflets which simultaneously decreases their opening and closing efficacy, and may shorten the leaflets leading to insufficiency [1].

The mechanisms by which AVLs maintain their structural and functional homeostasis is presently unclear, and although the role of the aortic valve interstitial cells (AVICs) is believed to be crucial, it is not known if their biosynthetic response is driven primarily by mechanical, biochemical, or a synergistic combination of both mechanisms. Valve interstitial cells (VICs) have been recognized for many years as a heterogeneous population of fibroblasts, secretory and contractile smooth muscle cells, and myofibroblasts, aptly named due to expression of both fibroblast and smooth muscle cell markers, primarily smooth muscle α-actin (SMA) [2-6]. Using micropipette aspiration, we have recently shown that isolated ovine VICs from the left side of the heart were significantly stiffer than the right side VICs [7]. Moreover, the mitral and aortic VICs were not only stiffer but also produced significantly more type I collagen, as determined by the surrogate, heat shock protein 47 (Hsp47). Hsp47 levels correlated well with cellular SMA among all VIC populations, which revealed a first-order approximation of their mechano-dependent biosynthesis. This finding implies that VICs are phenotypically and functionally tuned to actively remodel the ECM due to the synthetic demands necessary for normal tissue homeostasis.

The modulating environmental factors controlling AVIC contractility are uncertain. Additionally, it is unclear how mechanotransduction from the global and multi-modal stresses (i.e. planar tension, flexure, and shear stress) on AVLs translate to the cell and sub-cellular levels. Infiltration of neutral lipid and inflammatory cells is thought to initiate AVL calcification [8], and it is interesting to note that inflammatory cells (macrophages) are an excellent source of many growth factors and cytokines, notably transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1) [9]. This is of importance as TGF-β1 has been demonstrated to effectively alter the AVIC phenotype from a quiescent fibroblast to an activated and contractile myofibroblast in vitro [10, 11]. In vivo, this phenotypic shift is apparent when comparing VICs from normal, healthy valves with those from developing, diseased, and remodeling valves [6, 12, 13].

Therefore, we hypothesize that both cyclic, circumferential tension and TGF-β1 are modulating factors for the in situ AVIC phenotype and resulting biosynthetic state; hence, each were examined independently and in concert to determine their resulting isolated and synergistic effects. This was accomplished by exposing circumferential AVL tissue strips to extended tissue cultures under the following four scenarios and afterwards assaying AVIC contractile and synthetic proteins, bioactive TGF-β1, and performing standard histology for ECM composition:

Cyclic tension (Tension)

No loading with exogenously added TGF-β1 (TGF)

Neither loading nor exogenously added TGF-β1 (Null)

Cyclic tension with exogenously added TGF-β1 (Tension+TGF)

METHODS

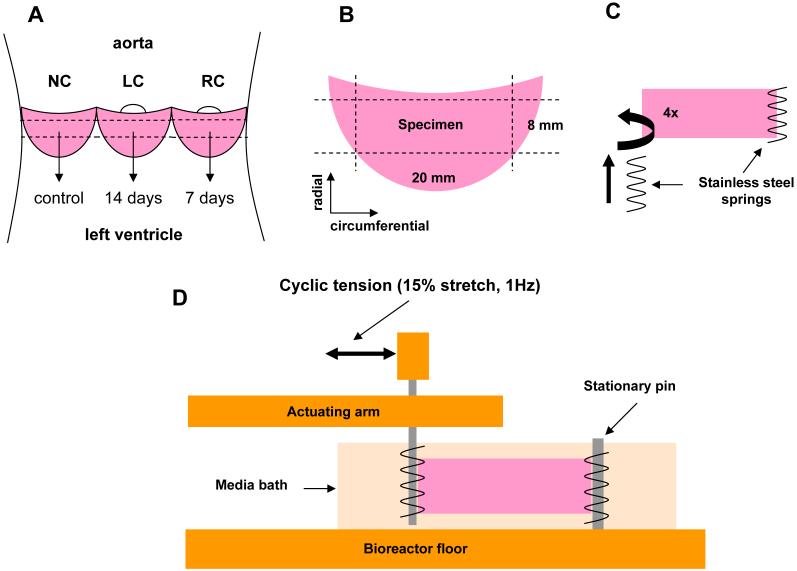

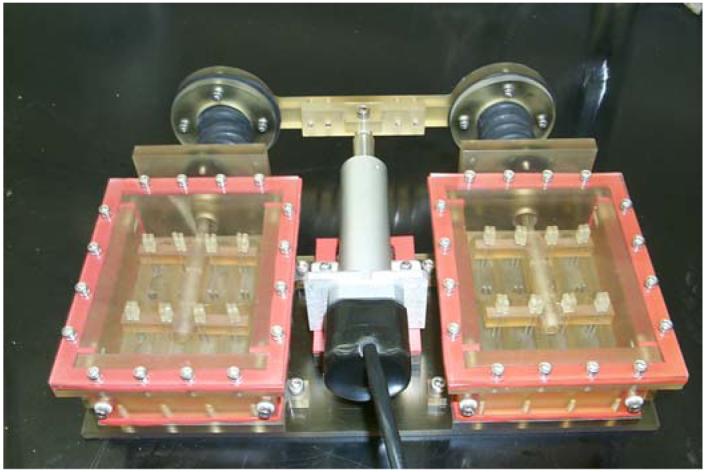

Bioreactor design

The tension bioreactor (Fig. 1) used in this study is similar to the previously described flexure bioreactor used for flexural stimulation of engineered valvular tissue [14, 15]. Cyclic stretch is applied to the samples by an environmentally sealed linear actuator (UltraMotion, Mattitick, NY) which is rigidly coupled to the base of the system and the cross-arm of the bioreactor. The cross-arm is coupled to the actuating arms penetrating each chamber via a hole that is protected with an accordion-style rubber bellow. Each actuating arm has two orthogonal crossbars with exiting holes into which stainless steel pins are inserted. These pins align directly across from the stationary pins to apply uni-directional tension to the specimen. Applied strain and strain rate are controlled with programmable Si Programmer software (Applied Motion Products, Watsonville, CA). The entire device, including lids, pins, and screws can be cold gas sterilized with ethylene oxide.

Figure 1.

Tension bioreactor used to house and mechanically train AVL strips. Each chamber has 8 wells, which allows 16 samples to receive the same mechanical stimulation simultaneously.

Tissue preparation

Porcine hearts were excised from young hogs (∼10mos., ∼250 lbs.) at a local USDA approved abattoir (Thoma Meat Mkt., Saxonburg, PA); for each treatment group four hearts were used. Intact aortic valves were excised on site and placed in preservation media (HypoThermosol HTS-FRS, BioLife Solutions, Binghamton, NY) at 4°C to assure maximal cell survival during transport [16]. Individual AVLs were excised in the lab and separated into left (LC), right (RC), and non coronary (NC) groups (Fig. 2A). Each AVL was then trimmed such that a tissue strip was formed measuring 20 mm circumferentially and 8 mm radially (Fig. 2B). An attempt was made to keep the endothelial cells viable by limited handling.

Figure 2.

Schematic of AVL strip preparation. A, Opened aortic root with leaflets shown. Each leaflet (NC, RC, and LC) was designated for specific treatment durations for all groups. B, Sample preparation from dissected leaflet to attain a circumferential AVL strip measuring (20 × 8 mm). C, Threading of stainless steel springs into both tissue ends; at least four puncture sites in the tissue were used to achieve a uniform stress distribution across the width of the sample. D, Side view of an AVL strip in the tension bioreactor. The actuating arm is coupled to the linear actuator of the system to apply 15% stretch to the sample.

Treatment configuration

Tissue strips from the LC and RC groups were prepared to be inserted into the tension bioreactor. In order to couple the tissue strips and the posts of the bioreactor, the tissue was threaded on both 8 mm ends with stainless steel springs (1 cm long × 2 mm diameter × 5 turns/cm, Fig. 2C) as reported previously for development of engineered heart valve tissues [17]. Each end of the tissue was penetrated at least four times by the spring, allowing a good stress distribution along the short axis of the tissue during loading. Tissue strips were then inserted into the tension bioreactor by sliding the springs onto the pins inserted into the floor of the culture well and the actuating arm of the bioreactor (Fig. 2D). To each well, 7mL of complete media was added (DMEM, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.5% fungizone, all from Gibco) and was subsequently changed every 24 hours.

For groups receiving biologically active TGF-β1 (0.5 ng/mL, T5050, Sigma) [11] media was prepared as 10× stock (5 mL aliquots), frozen (-20°C), and thawed for use daily to ensure that the growth factor remained active over the subsequent 24 hours. For groups receiving cyclic tension, the linear actuator was programmed to apply ∼15% stretch to the tissue at 1Hz. Groups receiving no cyclic tension were mounted into the bioreactor with the motor inactive and 0% stretch applied (tissues were slightly slack). Immediately after the LC and RC groups were loaded into the bioreactor, the NC samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen (-196°C) and stored at -80°C to serve as day 0 controls of AVIC function and tissue morphology. RC strips were exposed to protocols listed previously for 7 days and LC strips for 14 days (Fig. 2A). After each treatment, tissues were removed from the bioreactor and frozen as with the day 0 samples.

Cell and tissue analysis

Samples were thawed and the center 2 mm of the tissue, along the radial axis, was removed and fixed in 10% buffered formalin for standard histology. Sections were then paraffin-embedded, sectioned at 10μm, and stained with Movat’s pentachrome stain for ECM composition and distribution analysis. The average thickness of each leaflet was digitally calculated from the histology slides (SigmaScan, SYSTAT) to determine if there was any appreciable compression of the specimens during treatment. The remaining tissue was homogenized and the intra-AVIC proteins analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for SMA and Hsp47 as reported previously [7]. Hsp47, a molecular chaperone located in the endoplasmic reticulum, has been shown to facilitate proper secretion of type I collagen in multiple cell types [18-20], and has also been found to nearly eliminate proper collagen production in Hsp47-/- cells [21, 22]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that selectively transfecting smooth muscle cells with a retrovirus containing Hsp47 cDNA resulted in increases of both intra- and extracellular steady state type I collagen production, while Northern blots of total RNA showed a tandem increase in both Hsp47 and procollagen [18]. Hence, Hsp47 was deemed a suitable surrogate for type I collagen in this study; however, to validate the accuracy of Hsp47, all samples were additionally assayed by an ELISA for type I collagen C-terminal propeptide (CICP, Metra CICP EIA Kit, Quidel Corp.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Similarly, biologically active TGF-β1 was assayed with the TGF-β1 Emax® Immuno-Assay System (Promega Corp.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions [11].

As it is not possible to demarcate the cell type variability within the tissue, we assumed that the AVIC population is on a continuum which ranges from fibroblasts to myofibroblasts to smooth muscle cells. Therefore, all assays herein are lumped quantifications of the cell population. Based on previous work [6, 12, 13, 23, 24], there is strong support that the myofibroblast is highly responsible for active valvular tissue remodeling and is very prevalent in many valvular pathologies.

Statistics

ELISA values, thickness measurements, and bioactive TGF-β1 values are reported as mean ± standard error (SEM). For statistical comparison, all ELISAs and bioactive TGF-β1 were analyzed with a repeated measures two-way ANOVA for day and treatment group. Post testing was performed with the Tukey test. Thickness measurements were compared with ANOVA within each treatment group. All differences were deemed statistically significant for p<0.05.

RESULTS

All biochemical assay results are found in Table 1 (mean ± SEM). It was found that for all assays (Hsp47, SMA, CICP, and Bioactive TGF-β1) there was a significant difference (p<0.001) for time, treatment, and their interaction. Statistical comparisons that follow were preformed with the Tukey test.

Table 1.

Raw values (mean ± SEM) for each assay

| mean ± SEM n=4 | Day | SMA (ng/ml) | Hsp47 (ng/ml) | CICP (ng/ml) | Bioactive TGF-β1 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Null | 0 | 1.65 ± 0.04 | 1.34 ± 0.03 | 2.74 ± 0.07 | 46.78 ± 1.67 |

| 7 | 1.53 ± 0.03 | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 2.54 ± 0.07 | 52.43 ± 2.09 | |

| 14 | 1.15 ± 0.02 | 0.96 ± 0.02 | 2.12 ± 0.02 | 47.20 ± 1.64 | |

| Tension | 0 | 1.62 ± 0.05 | 1.16 ± 0.01 | 2.29 ± 0.10 | 52.20 ± 1.28 |

| 7 | 1.57 ± 0.03 | 1.51 ± 0.02 | 2.95 ± 0.23 | 66.86 ± 3.16 | |

| 14 | 1.82 ± 0.04 | 1.52 ± 0.04 | 2.98 ± 0.09 | 63.30 ± 1.09 | |

| TGF | 0 | 1.65 ± 0.02 | 1.41 ± 0.02 | 3.04 ± 0.13 | 50.23 ± 2.33 |

| 7 | 1.81 ± 0.02 | 1.73 ± 0.03 | 3.50 ± 0.15 | 117.50 ± 5.56 | |

| 14 | 1.96 ± 0.03 | 2.03 ± 0.04 | 4.23 ± 0.04 | 95.25 ± 1.70 | |

| Tension+TGF | 0 | 1.58 ± 0.02 | 1.30 ± 0.06 | 3.14 ± 0.12 | 55.43 ± 1.88 |

| 7 | 3.02 ± 0.05 | 3.42 ± 0.12 | 7.29 ± 0.19 | 621.25 ± 8.69 | |

| 14 | 3.87 ± 0.04 | 4.30 ± 0.07 | 8.72 ± 0.28 | 647.00 ± 8.13 | |

SMA and Hsp47 quantification

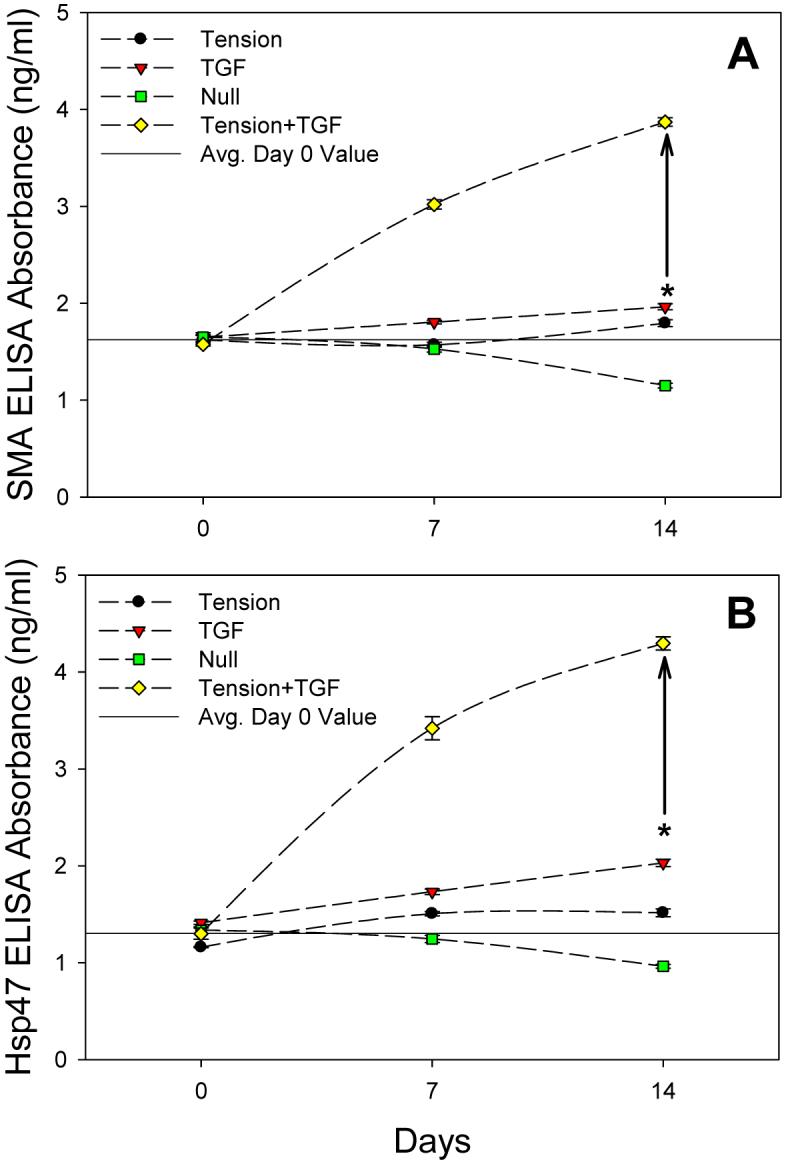

ELISA absorbance values for SMA (Fig. 3A) and Hsp47 (Fig. 3B) reveal very similar trends for each treatment over the duration of the experiment. All SMA data points are significantly different (p<0.05) except the following: no difference between any groups at day 0; no difference between Null and Tension at day 7; and no difference between day 0 and 7 for the Tension group (Fig. 3A). The Tension+TGF group was significantly greater (p<0.001) than all other groups at both days 7 and 14. All Hsp47 data points are significantly different (p<0.05) except the following: no difference between any groups at day 0 except between TGF and Tension (p=0.006); no difference between day 7 and 14 for the Tension group (Fig. 3B). The Tension+TGF group was significantly greater (p<0.001) than all other groups at both days 7 and 14.

Figure 3.

A, SMA ELISA results (mean ± SEM). Tension+TGF group significantly greater (p<0.001) than all other groups at 7 and 14 days. B, Hsp47 ELISA results (mean ± SEM). Tension+TGF group significantly greater (p<0.001) than all other groups at 7 and 14 days. Drawn asterisk (*) shows sum of Tension and TGF results individually at 14 days and drawn vertical line represents the difference between this sum and the Tension+TGF group. As a reference, the drawn horizontal line represents the average day 0 value of all groups.

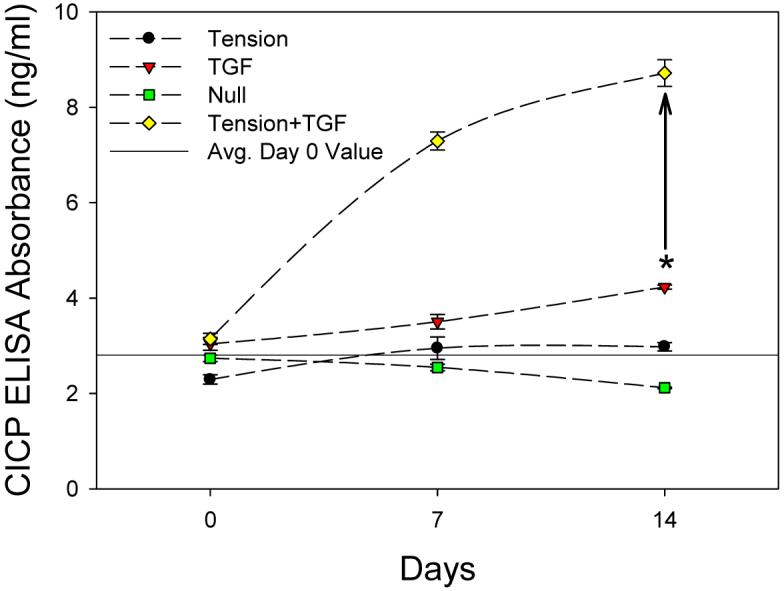

CICP quantification

While Hsp47 expression has been shown to be highly correlated with type I collagen biosynthesis [18-22], it was confirmed here by the use of a CICP ELISA (Fig. 4). All CICP data points are significantly different (p<0.05) except the following: no difference between Tension and Null groups or TGF and Null groups on day 0; no difference between day 0 and day 7 or day 7 and day 14 for the Null group; no difference between day 7 and 14 for the Tension group; and no difference between day 0 and 7 for the TGF group. As with Hsp47 (Fig. 3B), CICP values were significantly greater (p<0.001) for the Tension+TGF group at both 7 and 14 days, compared to all other groups (Fig. 4). Therefore, throughout the remainder of this manuscript, only Hsp47 will be discussed when referring to collagen biosynthesis, as the present result validates that increases in Hsp47 expression suitably represent increased type I collagen synthesis for AVICs. The drawn asterisk (*) on each graph in Figures 3 and 4 represents the cumulative effects of Tension and TGF at day 14 with the vertical arrow representing the difference between this value and the Tension+TGF group, which is considered the synergistic response of the two stimuli.

Figure 4.

CICP ELISA results (mean ± SEM). Tension+TGF group significantly greater (p<0.001) than all other groups at 7 and 14 days. The CICP results demonstrate that Hsp47 is suitable surrogate for type I collagen synthesis as their trends are nearly identical. Drawn asterisk (*) shows sum of Tension and TGF results individually at 14 days and drawn vertical line represents the difference between this sum and the Tension+TGF group. As a reference, the drawn horizontal line represents the average day 0 value of all groups.

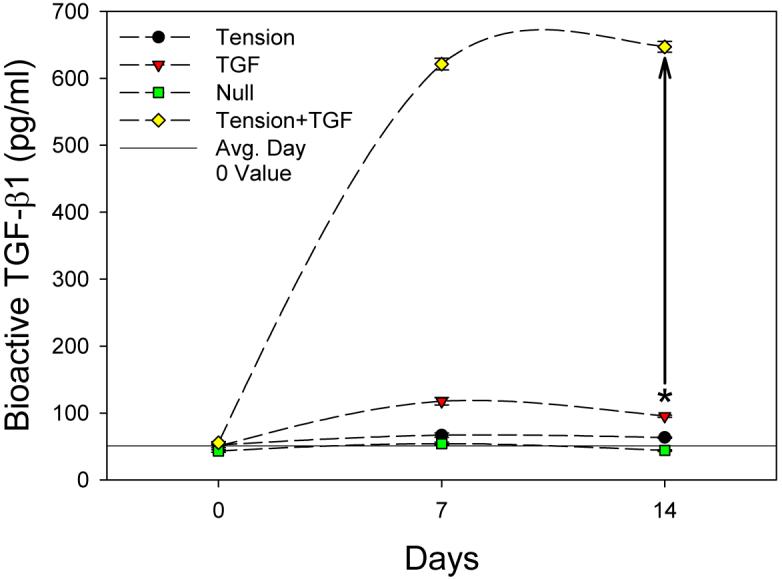

Bioactive TGF-β1 quantification

All bioactive TGF-β1 data points are significantly different (p<0.05) except the following: no difference between any groups on day 0; no difference between Tension and Null groups on day 7; no difference between day 0, 7, or 14 for Null group; and no difference between day 0, 7, or 14 for Tension group (Fig. 5). The Tension+TGF group was significantly greater (p<0.001) than all other groups at both days 7 and 14.

Figure 5.

Bioactive TGF (mean ± SEM) was statistically greater (p<0.001) for the Tension+TGF group compared to all other groups at 7 and 14 days. Drawn asterisk (*) shows sum of Tension and TGF results individually at 14 days and drawn vertical line represents the difference between this sum and the Tension+TGF group. As a reference, the drawn horizontal line represents the average day 0 value of all groups.

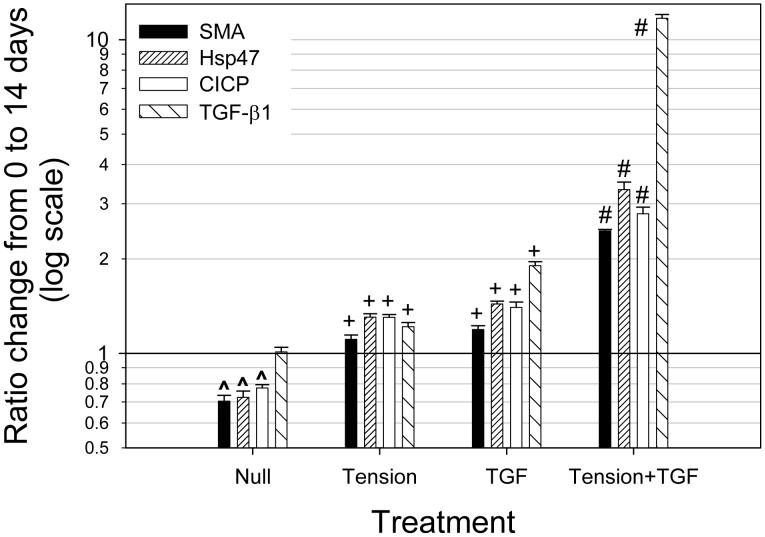

Ratio change due to 14 day treatment

Normalized results at day 14 (ratio of day 14/day 0) revealed a dramatic response for the Tension+TGF group; SMA, Hsp47, CICP, and bioactive TGF-β1 (Fig. 6) were significant greater (p<0.001, shown as # on Fig. 6) compared to all other groups. For the Null group, SMA, Hsp47, and CICP were all significantly less (p<0.05, shown as ^) at day 14 compared to day 0 (drawn line at unity represents day 0 values). For both Tension and TGF groups, SMA, Hsp47, CICP, and bioactive TGF-b1 were significantly greater (p<0.05, shown as +) at day 14 compared to day 0.

Figure 6.

Ratio change from 0 to 14 days (i.e. day 14/day 0) (mean ± SEM). Drawn line at unity represents day 0 values; ^ denotes significantly less (p<0.05) than unity, + denotes significantly greater (p>0.05) than unity, and # denotes significantly greater (p<0.001) than all other groups. NOTE: LOG SCALE.

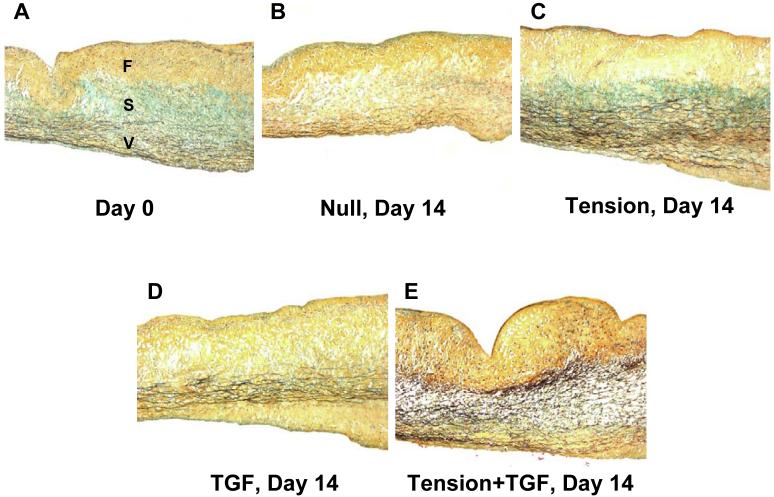

Histology of AVL strips

With Movat’s pentachrome stain (Fig. 7), ECM components are distinguished as proteoglycans (bluish-green), collagen (yellow), and elastin (dark violet); AVIC nuclei are dark red. All day 0 samples were similar with a distinct tri-layered architecture (fibrosa (F), composed of collagen; spongiosa (S), composed of proteoglycans; ventricularis (V), composed of elastin; Fig. 7A). Only 14 day samples are shown (Fig. 7B-E) as changes in the 7 day samples were not as distinctive.

Figure 7.

Movat’s pentachrome staining of the middle portion of treatment strips at day 0 and 14 days. A, Healthy porcine AVL (day 0). Note the distinct tri-layered structure (fibrosa (F): collagen (yellow, top); spongiosa (S): proteoglycans (bluish green, middle); ventricularis (V): elastin (dark violet fibers, bottom)). B, Null group at 14 days with no apparent proteoglycans and diminshed elastin fibers. C, Tension group at 14 days with similar ECM composition to day 0 (A), but more intense elastin fibers. D, TGF group at 14 days with no apparent proteoglycans and slightly diminished elastin fibers. E, Tension+TGF group at 14 days with no apparent protoeglycans, but intense elastin fibers in the central portion of the leaflet.

Null samples (Fig. 7B) appeared to have little or no proteoglycans in the spongiosa layer. Moreover, elastin fibers in the ventricularis layer were less pronounced than at day 0. Tension samples (Fig. 7C) showed the tri-layered structure seen at day 0.TGF samples (Fig. 7D) appeared to be similar to Null samples with few proteoglycans evident in the spongiosa layer. However, unlike the Null samples, TGF samples did have a clear ventricularis layer with numerous elastin fibers. Finally, Tension+TGF samples (Fig. 7E) did not have an apparent spongiosa layer, but had elastin fibers making up nearly half of the thickness of the leaflets. In all samples, AVIC nuclei were present and evenly dispersed throughout the thickness of the tissue. Thickness changes between groups at any time point were not statistically different (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

AVIC physiology: SMA and Hsp47 correlates

The overarching goal of this study was to determine the effects of cyclic tension and TGF-β1 on the in situ AVIC phenotype and biosynthetic function. To accomplish this, circumferential AVL strips were exposed to isolated and combined biomechanical and biochemical treatments for up to 14 days in vitro. Effective changes were determined by quantifying the contractile (SMA) and collagen biosynthetic (Hsp47, confirmed with CICP) proteins of the AVIC population and examining histology of the AVLs.

As we previously found that SMA and Hsp47 were well correlated between isolated ovine VICs of the four different heart valve leaflets [7], we were interested if this remained the case with in situ AVICs under different stimuli. Indeed, the results from this study further support the observation that VICs are highly sensitive to their environment, as SMA and Hsp47 trends were very similar for each treatment group (Figs. 3A and B). The mechanobiological consequence of this is that VICs are not only well tuned to their mechanical and biochemical environment, but are capable of adaptive cytoskeletal remodeling and resulting biosynthetic response, which likely serves to retain homeostasis within the tissue.

AVIC mediated-pathology: synergistic effects of Tension+TGF

It is our opinion that the most interesting finding from this study was the profound, synergistic effect of Tension+TGF on SMA (Fig. 3A) and Hsp47 (Fig. 3B) levels of the AVICs. While changes resulted from other treatments, their effects were not as substantial as those seen in the combined group. The effect of TGF-β1, in the presence of applied cyclic tension, to dramatically increase the intracellular SMA and Hsp47 levels reveals an important finding. Here, we demonstrate the ability to effectuate an altered AVIC state in the presence of TGF-β1, which would be analogous to TGF-β1-producing, infiltrating macrophages under quasi-normal AVL biomechanical function in vivo.

The effectiveness of added bioactive TGF-β1 was apparent in the TGF group (Fig. 5). However, the mechanism behind the substantial increase in bioactive TGF-β1 for the Tension+TGF group is not clear, as Tension alone revealed minimal differences in bioactive TGF-β1 at 7 or 14 days. While this sensitivity to TGF-β1 has been shown previously for AVICs in culture [10, 11, 25], it has yet, until now, to be demonstrated with AVICs in situ. After two weeks of the Tension+TGF treatment, the AVIC population was nearly 2.5-fold more contractile (by SMA quantification) and was producing ∼3-times as much type I collage (by Hsp47 and CICP quantification) compared to day 0 (Fig. 5).

The ramifications of this finding serve to directly implicate the AVIC as a contributor to AVL degenerative pathologies. Since cyclic tension can never be relieved in AVLs in-vivo, the introduction of TGF-β1 (e.g. by macrophage infiltration) would likely lead to a similar response in vivo that was observed here. The chronic effects of hyper-contractile and hyper-collagen producing AVICs are not entirely clear at the present time as this study was only conducted over a two week period; however, if TGF-β1 levels such as these are achieved in vivo over a period of months or years, the resulting state of the AVL architecture would likely no longer resemble that of healthy tissue. Additionally, while Tension alone had little effect on the ECM architecture compared to day 0 controls (Fig. 7A, C), TGF was similar to Null with a loss of the spongiosa; however, there was still an apparent layer of elastin. The combination of Tension+TGF (Fig. 7E) resulted in loss of the spongiosa layer with a substantial increase in elastin. Therefore, while elastin was not directly quantified in this study, it appears to be macroscopically conserved by the AVICs in the presence of TGF-β1 and further examination of this will be necessary in the future.

AVIC homeostasis: sensitivity to TGF-β1 and the role of cyclic tension

The general myofibroblast phenotype found elsewhere in the body is normally identified by the presence of SMA, which has been shown to be upregulated in the presence of TGF-β1 [26]. The efficacy of TGF-β1 is dependent on the co-localization of fibronectin (FN) splice variant ED-A-FN in the surrounding ECM [9]. However, it has been shown that the presence of both TGF-β1 and ED-A-FN were not sufficient to maintain the contractile phenotype of rat dermal myofibroblasts when mechanical tension was released from the tissue [27]. Hence, we speculated from the outset of this work that Tension alone would be able to maintain the in vivo AVIC protein levels, and that TGF alone would not be effective in this maintenance. This turned out not to be the case as TGF alone actually resulted in comparable or greater SMA and Hsp47 levels than Tension alone. The consequence of this finding reveals the sensitivity of the AVIC to surrounding levels of cytokines in the absence of applied mechanical stimuli. Though an interesting finding, this situation does not occur in vivo for AVLs.

During normal in vivo function, AVLs are exposed to cyclic flexure (during opening and closing), tension (when closed), and shear from passing blood (when opened), with tension dominating 60% of the cardiac cycle. Therefore, the effects of cyclic tension were thought to be a major contributor in AVIC mechanobiological function. Previously, static pressure [28] and constant shear [29] of AVLs has been unable to maintain the SMA+ AVIC phenotype; hence, we sought to examine the cellular response due to circumferential cyclic tension in the physiologic range. As expected, SMA and Hsp47 levels of the Tension group at day 14 most resembled those of day 0 compared to the other treatment groups. Moreover, the histological results (Fig. 7) reveal that the Tension group at 14 days was most similar to the day 0 controls with respect to ECM composition and architecture. This finding implies that under normal physiologic conditions, mechanical stimulation (particularly planar tension during diastole) is a key contributor to AVIC phenotypic modulation and resulting biosynthesis. Additionally, loss of proteoglycans in the spongiosa region of groups not receiving mechanical stimulation was not expected, as tension was believed to likely compress this region; however, it appears from the histology that these proteoglycans either dissociated on their own, the non-stimulated AVICs enzymatically digested them, or the AVICs were not able to actively synthesize new proteoglycans in the absence of applied tension.

The Null treatment resulted in concomitant decreases in all proteins assayed (Fig. 3 and 4) and loss of the tri-layered ECM architecture (Fig. 7B). This indicates that AVICs require mechanical stimulation or cytokines to remain biosynthetically active and normal. Though data points were only obtained up to two weeks, there is reason to believe that further decreases in both protein levels would occur at longer times. This finding is believed to be a directive of pre-implant mechanical conditioning that will likely be needed for a tissue engineered heart valve. As this was an exemplary tissue, with proper ECM architecture, cell-ECM connectivity, and cell-cell communication, the loss of in vivo-like qualities of the AVICs in the absence of mechanical stimulation further supports the need for proper conditioning of an engineered tissue prior to implantation.

Study rationale and limitations

In the present study, AV leaflets used for each treatment group at 0, 7, and 14 days came from the same valves. Chiefly, we assumed that the range of SMA and Hsp47 levels between the leaflets of the same aortic valve were small compared to the changes measured in this study due to applied treatments. This was based on results from our previous study where we quantified these proteins from each leaflet of two aortic valves [7] and found the range of protein levels to be fairly small (Hsp47=1.163 ± 0.047 ng/ml; SMA=1.638 ± 0.024 ng/ml; n=6). Thus, this experimental design allowed us to use a single leaflet from each valve (NC leaflet) essentially as its own control, so that changes at 7 and 14 days in the RC and LC leaflets resulted from the applied treatments.

The small differences between the means of any day 0 groups are believed to be a result of collecting specimens on different days from the abattoir. Indeed, consistent with this assumption was the observation in the current study that variation in the Hsp47 and SMA values for all day 0 means (Fig. 3) was very small. Because it was necessary to use slaughterhouse animals for this type of study, it was not possible to control variables such as diet, weight, and overall health of the animals (nor, screen these protein levels a priori); therefore, day 0 differences are believed to be due to valve-to-valve variability of the animals collected on different days. Moreover, due to the destructive nature of the assays, it was not possible to do repeated measures analysis with these samples. Therefore, with the above considerations, the experimental design and statistical comparison were deemed appropriate for the goals of the present study. Finally, changes resulting from each applied treatments over time was the focus of this work and differences for the Tension+TGF group, due to synergism, were far more substantial compared to all other groups, including those at day 0.

The results and interpretation presented here are predicated on the circumferential cyclic tension applied to the samples, and 15% stretch is within the normal physiologic range [30]. We have recently shown that AVICs undergo profound nuclear deformations during diastolic loading [31] and implicitly assumed that the main effect of tissue strain on AVICs is to induce cellular deformations to elicit key biological responses. In this previous study [31], we demonstrated that these cellular deformations occur at peak diastolic loading, where the circumferential strains are approximately 10% to 20% strain [32]. Thus, application of 15% strains to circumferentially oriented strips was a suitable approximation to the in vivo mechanical milieu. Moreover, the method of attachment of the tissue to the bioreactor actually is considered strip biaxial and not uniaxial [33], which is more physiologic because the strain in the radial direction is held at ∼0%. While the strain level used in this study was within the physiologic range, the strain rate used to achieve this level is far below that found in vivo. Currently, we have begun to examine high strain rate, tissue-level mechanics of heart valve leaflets [34], and plan on examining these effects on AVIC function in the near future, while also incorporating load measurement due to applied strain for more advanced biomechanical analyses.

Although AVIC survival was not directly quantified in this study, it has been previously demonstrated that extended static cultures of heart valve tissues contained predominantly viable VICs throughout the leaflet well past 30 days [35]. Additionally, an attempt was made to maintain an intact endothelium on the AVL strips with limited handling; however, examination of endothelial cells was not the focus of this study and their state was not assayed at any point. While the interaction between the AVICs and endothelial cells likely plays a key role in valve physiology and resulting pathologies, their interaction was beyond the scope of this study. Well controlled experiments are currently being planned to address this important topic.

Conclusions

This study was the first to examine the combined effects of cyclic tension and TGF-β1 on the AVIC contractile phenotype and resulting collagen biosynthesis. As in previous studies, TGF-β1 had an impact on AVICs in the absence of mechanical stimulation; however, this was the first examination of in situ AVIC response. Moreover, we demonstrated the ability to elicit an activated AVIC phenotype in the combined presence of Tension+TGF, which is extremely relevant for the genesis and possible perpetuation of AVL degenerative pathologies such as calcification and fibrosis. It is believed that results from this study aid in understanding the means by which AVICs maintain homeostasis, the etiology of certain degenerative AVL pathologies, and the development of protocols used to condition engineered valvular tissues.

Table 2.

AVL thickness (mean ± SEM)

| mean ± SEM n=4 | Day | Thickness (μm) |

|---|---|---|

| Null | 0 | 405 ± 38 |

| 7 | 365 ± 49 | |

| 14 | 377 ± 33 | |

| Tension | 0 | 417 ± 17 |

| 7 | 342 ± 48 | |

| 14 | 365 ± 14 | |

| TGF | 0 | 407 ± 38 |

| 7 | 352 ± 36 | |

| 14 | 403 ± 64 | |

| Tension+TGF | 0 | 385 ± 33 |

| 7 | 357 ± 36 | |

| 14 | 390 ± 45 | |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH: HL-68816 (MSS). WDM and GCE were supported by Pre-doctoral Fellowships from the American Heart Association (0515416U and 0415406U, respectively). The Children’s Heart Foundation supports the heart valve research of RAH. The authors would like to thank Dr. Frederick J. Schoen for his comments in the preparation of this manuscript.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the NIH: HL-68816 (MSS). WDM and GCE were supported by Pre-doctoral Fellowships from the American Heart Association (0515416U and 0415406U, respectively). The Children’s Heart Foundation supports the heart valve research of RAH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Otto CM, et al. Characterization of the early lesion of ‘degenerative’ valvular aortic stenosis. Histological and immunohistochemical studies. Circulation. 1994;90(2):844–53. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Messier RH, Jr., et al. Dual structural and functional phenotypes of the porcine aortic valve interstitial population: characteristics of the leaflet myofibroblast. Journal of Surgical Research. 1994;57(1):1–21. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1994.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor PM, et al. The cardiac valve interstitial cell. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2003;35(2):113–8. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filip DA, Radu A, Simionescu M. Interstitial cells of the heart valve possess characteristics similar to smooth muscle cells. Circulation Research. 1986;59(3):310–320. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulholland DL, Gotlieb AI. Cell biology of valvular interstitial cells. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 1996;12(3):231–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabkin-Aikawa E, et al. Dynamic and reversible changes of interstitial cell phenotype during remodeling of cardiac valves. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13(5):841–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merryman WD, et al. Correlation between heart valve interstitial cell stiffness and transvalvular pressure: implications for collagen biosynthesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290(1):H224–31. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00521.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards JE. Calcific aortic stenosis: pathologic features. Mayo Clin Proc. 1961;36:444–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters T, et al. Wound-healing defect of CD18(-/-) mice due to a decrease in TGF-beta1 and myofibroblast differentiation. Embo J. 2005;24(19):3400–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker GA, et al. Valvular myofibroblast activation by transforming growth factor-beta: implications for pathological extracellular matrix remodeling in heart valve disease. Circ Res. 2004;95(3):253–60. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000136520.07995.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cushing MC, Liao JT, Anseth KS. Activation of valvular interstitial cells is mediated by transforming growth factor-beta1 interactions with matrix molecules. Matrix Biol. 2005;24(6):428–37. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabkin E, et al. Activated interstitial myofibroblasts express catabolic enzymes and mediate matrix remodeling in myxomatous heart valves. Circulation. 2001;104(21):2525–32. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aikawa E, et al. Human semilunar cardiac valve remodeling by activated cells from fetus to adult: implications for postnatal adaptation, pathology, and tissue engineering. Circulation. 2006;113(10):1344–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelmayr GC, Jr., et al. The independent role of cyclic flexure in the early in vitro development of an engineered heart valve tissue. Biomaterials. 2005;26(2):175–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelmayr GC, Jr., et al. A novel bioreactor for the dynamic flexural stimulation of tissue engineered heart valve biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2003;24(14):2523–32. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merryman WD, et al. The effects of cellular contraction on aortic valve leaflet flexural stiffness. J Biomech. 2006;39(1):88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelmayr GC, Jr., et al. Cyclic flexure and laminar flow synergistically accelerate mesenchymal stem cell-mediated engineered tissue formation: Implications for engineered heart valve tissues. Biomaterials. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocnik EF, et al. Functional linkage between the endoplasmic reticulum protein Hsp47 and procollagen expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(41):38571–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tasab M, Batten MR, Bulleid NJ. Hsp47: a molecular chaperone that interacts with and stabilizes correctly-folded procollagen. Embo J. 2000;19(10):2204–11. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sauk JJ, Nikitakis N, Siavash H. Hsp47 a novel collagen binding serpin chaperone, autoantigen and therapeutic target. Front Biosci. 2005;10:107–18. doi: 10.2741/1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishida Y, et al. Type I Collagen in Hsp47-null Cells Is Aggregated in ER and Deficient in N-Propeptide Processing and Fibrillogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2006 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagai N, et al. Embryonic lethality of molecular chaperone hsp47 knockout mice is associated with defects in collagen biosynthesis. J Cell Biol. 2000;150(6):1499–506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabkin E, et al. Evolution of cell phenotype and extracellular matrix in tissue-engineered heart valves during in-vitro maturation and in-vivo remodeling Journal of Heart Valve Disease 2002113308–14. discussion 314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabkin-Aikawa E, et al. Clinical pulmonary autograft valves: pathologic evidence of adaptive remodeling in the aortic site. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128(4):552–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohler ER, 3rd, et al. Identification and characterization of calcifying valve cells from human and canine aortic valves. J Heart Valve Dis. 1999;8(3):254–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desmouliere A, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122(1):103–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinz B, et al. Mechanical tension controls granulation tissue contractile activity and myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(3):1009–20. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61776-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xing Y, et al. Effects of constant static pressure on the biological properties of porcine aortic valve leaflets. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2004;32(4):555–562. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000019175.12013.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weston MW, Yoganathan AP. Biosynthetic activity in heart valve leaflets in response to in vitro flow environments. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2001;29(9):752–63. doi: 10.1114/1.1397794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billiar KL, Sacks MS. Biaxial mechanical properties of the natural and glutaraldehyde treated aortic valve cusp--Part I: Experimental results. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2000a;122(1):23–30. doi: 10.1115/1.429624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang H-YS, Liao J, Sacks MS.Effects of transvalvular pressure on aortic valve interstitial cell nuclear aspect ratio Annals of Biomedical Engineering Submitted [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adamczyk MM, Vesely I. Characteristics of compressive strains in porcine aortic valves cusps. J Heart Valve Dis. 2002;11(1):75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stella J, Sacks MS.On the biaxial mechanical properties of the layers of the aortic valve leaflet Journal of Biomechanial Engineering in-press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grashow JS, Yoganathan AP, Sacks MS. Biaixal Stress-Stretch Behavior of the Mitral Valve Anterior Leaflet at Physiologic Strain Rates. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-9027-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allison DD, et al. Cell viability mapping within long-term heart valve organ cultures. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13(2):290–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]