Abstract

Aging is associated with increased vulnerability to neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease and greater neuronal deficits after stroke and epilepsy. Emerging studies have implicated increased levels of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) for the neuronal loss associated with aging related disorders. Recent evidence demonstrates increased expression of voltage gated Ca2+ channel proteins and associated Ca2+ currents with aging. However, a direct comparison of [Ca2+]i levels and Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms in hippocampal neurons acutely isolated from young and mid-age adult animals has not been performed. In this study, Fura-2 was used to determine [Ca2+]i levels in CA1 hippocampal neurons acutely isolated from young (4–5 months) and mid-age (12–16 months) Sprague-Dawley rats. Our data provide the first direct demonstration that mid-age neurons in comparison to young neurons manifest significant elevations in basal [Ca2+]i levels. Upon glutamate stimulation and a subsequent [Ca2+]i load, mid-age neurons took longer to remove the excess [Ca2+]i in comparison to young neurons, providing direct evidence that altered Ca2+ homeostasis may be present in animals at significantly younger ages than those that are commonly considered aged (≥ 24 months). These alterations in Ca2+ dynamics may render aging neurons more vulnerable to neuronal death following stroke, seizures or head trauma. Elucidating the functionality of Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms may offer an understanding of the increased neuronal loss that occurs with aging, and allow for the development of novel therapeutic agents targeted towards decreasing [Ca2+]i levels thereby restoring the systems that maintain normal Ca2+ homeostasis in aged neurons.

Keywords: Aging, Fura-2, Acute dissociation of neurons, Calcium

There may be very few topics that have more interest for scientists and common man alike than slowing aging and aging related deficits and extending life expectancy. Biomedical breakthroughs against infectious diseases coupled with decreased fertility and increased life expectancy is resulting in a growing aging population worldwide [24]. Over the next 25 years, worldwide, the number of people 65 years and older is projected to increase approximately from 550 million to 973 million [12]. This anticipated increase in the number of older persons would have dramatic consequences on public health care systems, informal care giving, and even the pension systems [8]. Thus, aging is not only an important biological issue but also a crucial socioeconomic factor affecting an ever-increasing aging population.

One aspect of aging research that has come to the forefront is the age related control of the ion messenger, calcium (Ca2+). Calcium is a ubiquitous intracellular second messenger that plays a key role in variety of cellular functions including growth, survival and death [1]. Calcium levels are tightly regulated within the neurons via complex homeostatic mechanisms. It has been suggested that altered Ca2+ sensitivity or abnormal Ca2+ regulation in neurons are involved in the aging process, and contribute to the gradual loss of neurons in Alzheimer’s Disease and their increased vulnerability to cell death after seizure or stroke [2, 5, 14, 15, 19]. Thus, a better understanding of how neurons handle Ca2+ with advancing age would allow us to ascertain their increased vulnerability to various insults which lead to the development and progression of aging related deficits.

It is difficult to conduct Ca2+ studies on intact animal models of aging, since very few experimental assays are suited to evaluating intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) dynamics in the whole animal. Alternatively, neurons in culture allowed to grow old (days in vitro >20), the so-called “aging in a dish” model, have been used for aging related studies [28]. We have utilized a novel method to evaluate [Ca2+]i levels and Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms in neurons acutely isolated from intact animals [17, 18]. Using this technique we tested the hypothesis that aging is associated with elevated [Ca2+]i levels and altered Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms in hippocampal neurons. The majority of studies on aging have utilized animals at 3–4 months (young) or 24–26 months (old) age. Here we used mid-age adult animals (12–16 months) to study age-dependent alterations in Ca2+ dynamics. Our studies provide the first measurement of increased basal [Ca2+]i. levels and altered Ca2+ homeostasis in neurons acutely isolated from mid-age versus young rats. Given the critical relationship between prolonged Ca2+ elevations and activation of neurotoxic signaling cascades, it is plausible that this difference could possibly contribute to the increased vulnerability of senile neurons to cell death after brain injury.

Hippocampal CA1 neurons were acutely isolated by a modification of the methods described previously [17, 18]. The brains from young and mid-age animals were rapidly dissected and placed in a 4°C chilled oxygenated (95% O2-5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid solution (aCSF) composed of (in mM) 201 sucrose, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaHPO4, 6 MgCl2, 0.2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, MK-801 (1 μM) and 10 glucose (solution A). Hippocampal slices of 450 μm were cut on a 12° agar ramp with a vibratome sectioning system (Series 2000, Technical Products International, St. Louis, MO) and incubated for 10 min in an oxygenated medium at 34°C containing (in mM) 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 6 MgCl2, 0.2 CaCl2, 25 glucose, and 20 PIPES, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH (solution B). Slices were then treated with 8 mg/ml of Protease XXIII (Sigma Chemical Co.) in solution B for 6–8 min and then thoroughly rinsed with solution B. The CA1 region was visualized in a dark background with the help of a dissecting microscope and tissue chunks were excised. These tissue preparations were then triturated in solution B with a series of Pasteur pipettes of decreasing diameter at 4°C in the presence of acetoxymethyl (AM) form of high affinity Ca2+ indicator Fura-2AM (1 μM) in order to load the cells prior to [Ca2+]i measurements. The resulting cell suspension was then placed in the center of poly-L-lysine coated Lab-Tek® two-well cover glass chambers (Nalge-Nunc International, Naperville, IL) and immediately placed in a humidified oxygenated dark chamber at 37°C for 1 h. Fura-2 was washed off with solution B and the loaded cells were allowed to equilibrate for 15 min allowing the cellular esterases to cleave the dyes from their AM forms. The dish was then constantly perfused with solution B via a gravity feed perfusion system at a rate of approximately 2–3 ml/min. For generation of the [Ca2+]i decay curves, a [Ca2+]i load was invoked by application of glutamate (50 μM) + glycine (10 μM) in solution B for 1 min using a rapid perfusion system.

Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester was loaded in the neurons and then transferred to a heated stage (37°C) of an Olympus IX-70 inverted microscope coupled to an ultra-high-speed fluorescence imaging system (Olympus/Perkin-Elmer). Ratio images were acquired by using alternating excitation wavelengths (340/380 nm) with a filter wheel (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and fura filter cube at 510/540 nm emissions with a dichroic mirror at 400 nm. Image pairs were captured and digitized every 15s, and the images at each wavelength were averaged over four frames and corrected for background fluorescence by imaging a non-indicator loaded field.

An in situ Ca2+ calibration curve was employed to convert fluorescent ratios to Ca2+ concentrations [18]. Baseline ratios of Fura-2-loaded hippocampal neurons were measured for ~5 min in recording solution. The solution was changed to a calibration buffer (100 mM KCl, 10 mM Ca- EGTA, 1 mM free Mg2+, 10 mM MOPS, pH=7.2 (Molecular Probes) supplemented with the ionophore, 5 μM bromo-A23187 (Molecular Probes). This high Ca2+, calibration buffer (≈39 μM Ca2+) was used to measure the maximum ratio value, Rmax. The bath solution was then changed to a low Ca2+ calibration buffer (≈0 μM Ca2+) (100 mM KCl, 10 mM Free-EGTA, 1 mM free Mg2+, 10 mM MOPS, pH=7.2) supplemented with 5-μM bromo-A23187 to determine the minimum ratio value, Rmin. These ratio values, after background correction, were used to calculate [Ca2+]i using the equation: [Ca2+]i = (KdSf2/Sb2)(R−Rmin)/(Rmax−R) where R is the 340/380 ratio at any time; Sf2 is the absolute value of the corrected 380 nm signal at R min; S b2 is the absolute value of the corrected 380 nm signal at R max; and the Kd is 224 nM. [Ca2+]i data was collected using Merlin software and statistically analyzed and plotted using Sigmaplot® (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Repeat measure analysis of variance of Ca2+ data was performed on every second data point sampled (every other minute). The significance of data was tested by Student’s paired or unpaired t-test wherever appropriate.

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed to determine membrane potential and input resistance using Axopatch 200A amplifier and Pclamp9 software (Axon Instruments). Fire polished borosilicate glass pipettes had a resistance of 7–10 mΩ when filled with internal solution containing: (in mM) 140 K+ gluconate, 10 HEPES and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.2, 290 ± 10 mosM). Extracellular solution contained (in mM) 145 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 2 CaCl2 and 1 MgCl2 (pH 7.3, 290 ± 10 mosM). The input resistance was determined by short hyperpolarizing voltage steps from a −60 mV holding potential. The Student’s t-test was employed to determine statistical differences in membrane potential or input resistance. The α value was set at p < 0.05.

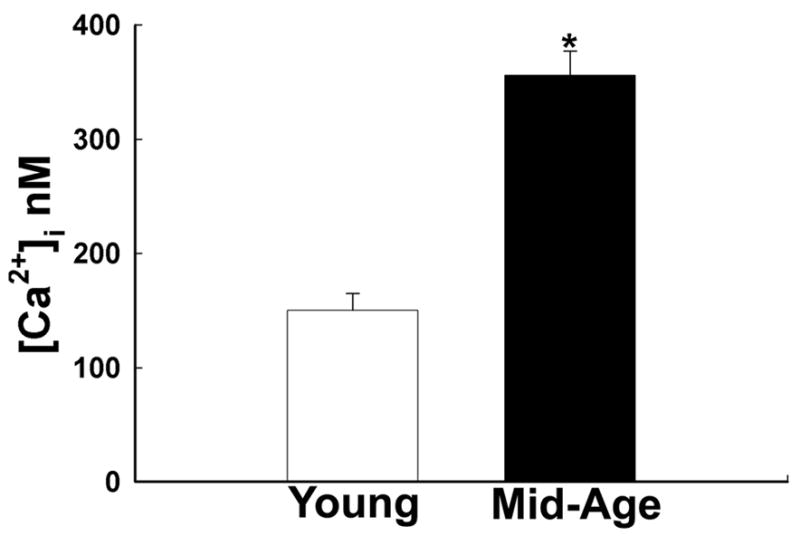

Using fluorescent microscopy techniques we measured [Ca2+]i in hippocampal neurons acutely isolated from both young (4–5 months) and mid-age (12–16 months) Sprague Dawley rats. Young neurons (n=122) exhibited mean basal [Ca2+]i values of 150.24 ± 15.32 nM. Neurons (n=141) isolated from mid-age animals exhibited significantly higher basal [Ca2+]i levels of 356.12 ± 21.14 nM (p<0.005) as illustrated in Fig. 1. To our knowledge this finding represents the first direct measurement of [Ca2+]i levels in acutely isolated hippocampal neurons from young and mid-age rats. Although our previous studies have not demonstrated major changes in [Ca2+]i due to acute isolation techniques [18], it is possible that the procedure of acute isolation could selectively injure mid-age neurons resulting in elevated basal [Ca2+]i levels. One way to assess the viability of the studied neurons would be to compare basic electrophysiological properties such as membrane potential and input resistance. Young and mid-age neurons had mean membrane potential of −64.2 ± 4.8 mV and −61.6 ± 3.4 mV and mean input resistance of 760 ± 108 MΩ and 810 ± 120 MΩ, respectively. These values were not different from each other (n=18, p=0.79 and p=0.23 respectively).

Figure 1.

Aging is associated with increased basal [Ca2+]i levels. Absolute [Ca2+]i levels in young and mid-age neurons were obtained after using a calibration curve for the Fura-2 Ca2+ indicator. Neurons from mid-age animals (12–16 months) exhibited a statistically significant increase when compared to the neurons isolated young animals (4–5 months) (* p<0.005).

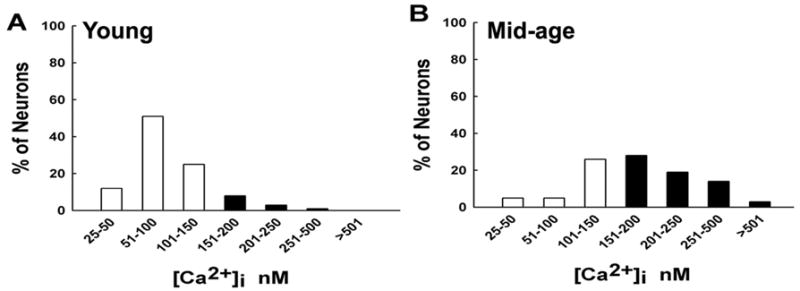

The distribution of [Ca2+]i levels for young and mid-age neurons is shown in Fig. 2. Approximately 60% of young neurons had basal [Ca2+]i values between 51–100 nM. Conversely, over 50% of the mid-age neurons had [Ca2+]i levels higher than 150 nM. This demonstrates that the shift to the higher [Ca2+]i levels exhibited by mid-age neurons was a result of consistently higher basal [Ca2+]i levels in a larger proportion of the mid-age neurons. These studies indicate that mid-age neurons have a defect in the ability to maintain a normal [Ca2+]i level and they function at higher basal [Ca2+]i levels.

Figure 2.

Distribution of [Ca2+]i levels for young vs. mid-age CA1 neurons. Both young and mid-age neurons displayed a normal distribution of [Ca2+]i levels. Approximately 60% of young neurons had basal [Ca2+]i values between 51–100 nM. Conversely, over 50% of the mid-age neurons had [Ca2+]i levels higher than 150 nM. Thus there was a shift towards higher [Ca2+]i levels in mid-age neurons compared to young neurons.

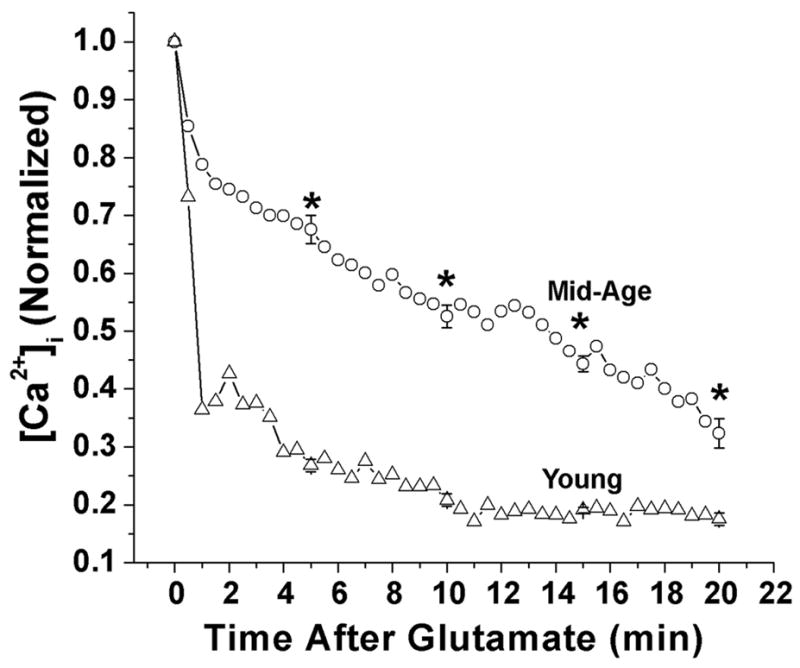

Glutamate treatment has been shown to effectively elicit an increase in [Ca2+]i, producing a [Ca2+]i load in neurons [15, 17, 18]. In order to investigate effects of aging on alterations in Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms, the ability of young and mid-age neurons to handle a given load of Ca2+ was assessed by challenging the neurons with glutamate. The quantitated values for the glutamate recovery curves for young and mid-age neurons are shown in Fig. 3. The decay curves were generated by calculating the mean [Ca2+]i levels at 15-s intervals and then normalizing these mean [Ca2+]i levels to a maximum value of 1. The resultant [Ca2+]i decay curves from the highest point after the glutamate exposure are displayed. Peak glutamate induced Ca2+ levels were not different between young and mid-age neurons (data not shown). When challenged with 50 μM glutamate treatment for 1 min, the young neurons (n = 15) were able to attain pre-glutamate [Ca2+]i values in 13.42 ± 4.38 min while the [Ca2+]i levels in the mid-age neurons (n = 20) did not reach basal values even after 40 min post-glutamate exposure. The time of the complete restoration of [Ca2+]i to the basal pre-glutamate level was at least 4–5-times longer in mid-age neurons. Thus, mid-age neurons had a significant delayed recovery in comparison to young neurons (p<0.005). The results demonstrate that while aging did not affect the peak level of [Ca2+]i in response to a glutamate stimulation, it significantly altered the ability of mid-age neurons to restore elevated [Ca2+]i to basal levels. Thus, aging neurons demonstrated chronically higher basal [Ca2+]i levels and prolonged elevations of [Ca2+]i following excitatory stimulation.

Figure 3.

[Ca2+]i decay curves for the young and mid-age neurons after a high [Ca2+]i load (50 μM glutamate for 1-min). Mid-age neurons demonstrated a delayed recovery that was statistically significant than the young neurons (*p<0.005, n=15 for young neurons and n=19 for mid-age neurons). Thus neurons from mid-age rats had a diminished ability to handle Ca2+ loads compared to neurons from young rats.

Cytosolic Ca2+ is maintained at a low level (50–200 nM) in resting cells against an extracellular concentration of ~ 2 mM. Neuronal [Ca2+]i is tightly regulated by complex regulatory mechanisms that balance extracellular Ca2+ entry or intracellular release with buffering, sequestration, and extrusion of the ion. While brief elevations in [Ca2+]i are required for controlling membrane excitability and modulating essential processes such as learning, memory, gene transcription and other major cellular functions, chronic elevations in [Ca2+]i trigger neurotoxic signaling cascades that lead to cell death [1, 5]. The present study shows that mid-age neurons not only demonstrate higher basal [Ca2+]i levels, but also manifest a significant shift towards higher [Ca2+]i levels compared to young neurons and a diminished ability to handle Ca2+ loads. The differences observed in relative [Ca2+]i levels and metabolic clearance between dissociated neurons from young and mid-age rats could have significant consequences for neurological disease such as epilepsy, stroke and brain injury. Using a similar approach, we have demonstrated that neurons isolated from one-year-old epileptic animals have higher basal [Ca2+]i levels and alterations in Ca2+ dynamics compared to neurons isolated from age-matched control animals [18]. Further investigations on aging related changes in Ca2+ dynamics from epileptic or hypoxic animals may advance our knowledge on the vulnerability of older neurons to injury.

Several studies have been performed employing preparations of synaptosomes, isolated mitochondria, dissociated neurons, neuronal cultures, and brain slices to study alterations in Ca2+ dynamics associated with aging [26]. While these studies demonstrate variability regarding elevated resting [Ca2+]i in aged neurons, a more consistent theme has been that the older neurons manifest a decreased Ca2+ buffering capacity and they demonstrate a delayed recovery towards restoring basal [Ca2+]i following stimulation [26]. Recently a major study by Thibault et al., evaluated [Ca2+]i in hippocampal neurons in brain slices from Fisher 344 rats at 3–5 months (young) and 24–27 months (old) age using Indo-1[20]. This bench mark study did not find significant differences in resting [Ca2+]i between young and old neurons in slices; however, [Ca2+]i was elevated in aged versus young rats during comparable degrees of synaptic and voltage-dependent activation. In contrast, a more recent study by Tonkikh et al., [22] showed that [Ca2+]i was increased in hippocampal slices from aged Fisher 344 rats compared to young rats. Thus there is disagreement as to the resting [Ca2+]i in young and old neurons even in brain slices which is considered to be more physiologically relevant preparation to study aging. Our studies demonstrate that aging process affects both [Ca2+]i levels and Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms. These findings highlight the importance of rigorously investigating the role of altered [Ca2+]i regulating systems in the aging process. Several factors could account for the discrepancy found in the aging literature regarding resting levels of [Ca2+]i, including differences in the tissue preparations, fluorescent indicator, strain of the animals or the duration for which slices/neurons are kept in vitro before [Ca2+]i determination [28]. In addition, although the methods of estimating [Ca2+]i using ratiometric indicators have been widely used by numerous investigators, it is important to acknowledge that these measurements represent the best approximations that we have of [Ca2+]i levels. Tissue preparation, incomplete indicator hydrolysis, dye loss, quenching, and shifts in the absorption and emission spectra may cause difficulties in using ratiometric indicators for estimating cytosolic free Ca2+. Emphasis should be placed on maintaining appropriate internal controls and on evaluating confounding factors such as inter-species and inter-strain variations and methods of tissue or neuronal isolation. Thus, while the search for better experimental techniques for [Ca2+]i imaging and aging models continues, the data obtained from currently available methods provide the best estimate of changes in [Ca2+]i.

There is growing body of evidence indicating an increase in expression and function of L-type Ca2+ channel protein with aging. Thus, there are reports of increased Ca2+ currents, subunit expression, and single-channel densities with aging [3, 4, 10, 16, 21, 25]. However, this may not necessarily translate into an increase in the absolute number of Ca2+ channels. It could simply mean an increase in the number of available functional channels. Indeed, a reduction in the binding affinity and sensitivity of [3H] nitrendipine to Ca2+ has been observed in aged rats [9] and autoradiographic studies have shown no age-related increases in the distribution and density of L-type and N-type Ca2+ channels [11]. However, decreases in the levels of Ca2+ binding proteins such as calbindin, calretinin and parvalbumin have been reported in older mammalian brain [7, 13, 27]. Further, a decreased Ca2+ buffering capacity of sarcoplasmic endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase has been found in aging sympathetic neurons [23] and myocardium [30]. There is also mounting evidence that Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from ryanodine receptors on the endoplasmic reticulum may be altered in some models of aging and Alzheimer’s Disease [6]. In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction as a result of age-dependent alterations in [Ca2+]i homeostasis has also been observed in cerebellar granule neurons in brain slices [29]. It will be interesting to evaluate the functionality of Ca2+ homeostatic mechanisms in future studies. Thus, these aging related changes not only increase the Ca2+ entry into the neurons but also decrease the capacity of neurons to buffer [Ca2+]i resulting in a higher basal [Ca2+]i. We have estimated basal [Ca2+]i levels in the acutely isolated hippocampal neurons at an earlier age in the rat that represents late middle age in humans. It is not known whether changes in [Ca2+]i dynamics begin in the early stages of neuronal senescence. Our data provide the first evidence that altered Ca2+ homeostasis occurs in animals at significantly younger ages than those that are commonly considered aged (≥ 24 months). This finding has important implications, since it would suggest that therapies for aging related changes in Ca2+ homeostatic systems could be initiated during middle age. Further research into the molecular mechanisms mediating these critical changes in Ca2+ homeostatic systems could help better understand the pathophysiology of aging.

Acknowledgments

NINDS Grants RO1NS051505, RO1NS052529 and UO1 NS058213, the Milton L. Markel Alzheimer’s Disease Research Fund and the Sophie and Nathan Gumenick Neuroscience Research Fund to RJD supported this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mohsin Raza, Department of Physiology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298.

Laxmikant S. Deshpande, Department of Neurology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298.

Robert E. Blair, Department of Neurology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298

Dawn S. Carter, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298

Sompong Sombati, Department of Neurology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298.

Robert J. DeLorenzo, Departments of Neurology, Pharmacology and Toxicology, and Biochemistry, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA 23298

References

- 1.Arundine M, Tymianski M. Molecular mechanisms of calcium-dependent neurodegeneration in excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. 2003;34:325–37. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brzyska M, Elbaum D. Dysregulation of calcium in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2003;63:171–83. doi: 10.55782/ane-2003-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell LW, Hao SY, Thibault O, Blalock EM, Landfield PW. Aging changes in voltage-gated calcium currents in hippocampal CA1 neurons. JNeurosci. 1996;16:6286–6295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06286.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen KC, Blalock EM, Thibault O, Kaminker P, Landfield PW. Expression of alpha 1D subunit mRNA is correlated with L-type Ca2+ channel activity in single neurons of hippocampal “zipper” slices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4357–4362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070056097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delorenzo RJ, Sun DA, Deshpande LS. Cellular mechanisms underlying acquired epilepsy: the calcium hypothesis of the induction and maintainance of epilepsy. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105:229–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gant JC, Sama MM, Landfield PW, Thibault O. Early and Simultaneous Emergence of Multiple Hippocampal Biomarkers of Aging Is Mediated by Ca2+-Induced Ca2+ Release. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3482–3490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4171-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geula C, Bu J, Nagykery N, Scinto LF, Chan J, Joseph J, Parker R, Wu CK. Loss of calbindin-D28k from aging human cholinergic basal forebrain: relation to neuronal loss. J Comp Neurol. 2003;455:249–59. doi: 10.1002/cne.10475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goulding MR, Rogers ME, Smith SM. Public Health and Aging: Trends in Aging - United States and Worldwide. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003 Feb 14;:101–4. 106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Govoni S, Rius RA, Battaini F, Bianchi A, Trabucchi M. Age-related reduced affinity in [3H]nitrendipine labeling of brain voltage-dependent calcium channels. Brain Res. 1985;333:374–377. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herman JP, Chen KC, Booze R, Landfield PW. Up-regulation of α1D Ca2+ channel subunit mRNA expression in the hippocampus of aged F344 rats. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:581–7. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly KM, Kume A, Albin RL, Macdonald RL. Autoradiography of L-type and N-type calcium channels in aged rat hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and neocortex. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00178-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinsella K, Velkoff V. An Aging World: 2001, U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2001. series P95/01-1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krzywkowski P, De Bilbao F, Senut MC, Lamour Y. Age-related changes in parvalbumin- and GABA-immunoreactive cells in the rat septum. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:29–40. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)80005-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Limbrick DD, Jr, Churn SB, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Inability to restore resting intracellular calcium levels as an early indicator of delayed neuronal cell death. Brain Res. 1995;690:145–156. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limbrick DD, Jr, Pal S, DeLorenzo RJ. Hippocampal neurons exhibit both persistent Ca2+ influx and impairment of Ca2+ sequestration/extrusion mechanisms following excitotoxic glutamate exposure. Brain Res. 2001;894:56–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porter NM, Thibault O, Thibault V, Chen KC, Landfield PW. Calcium channel density and hippocampal cell death with age in long-term culture. JNeurosci. 1997;17:5629–5639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05629.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raza M, Blair RE, Sombati S, Carter DS, Deshpande LS, DeLorenzo RJ. Evidence that injury-induced changes in hippocampal neuronal calcium dynamics during epileptogenesis cause acquired epilepsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17522–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408155101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raza M, Pal S, Rafiq A, DeLorenzo RJ. Long-term alteration of calcium homeostatic mechanisms in the pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res. 2001;903:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun DA, Sombati S, Blair RE, DeLorenzo RJ. Long-lasting alterations in neuronal calcium homeostasis in an in vitro model of stroke-induced epilepsy. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thibault O, Hadley R, Landfield PW. Elevated postsynaptic [Ca2+]i and L-type calcium channel activity in aged hippocampal neurons: relationship to impaired synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9744–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09744.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thibault O, Landfield PW. Increase in single L-type calcium channels in hippocampal neurons during aging. Science. 1996;272:1017–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tonkikh A, Janus C, El-Beheiry H, Pennefather PS, Samoilova M, McDonald P, Ouanounou A, Carlen PL. Calcium chelation improves spatial learning and synaptic plasticity in aged rats. ExpNeurol. 2006;197:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai H, Pottorf WJ, Buchholz JN, Duckles SP. Adrenergic Nerve Smooth Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Buffering Declines with Age. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UnitedNations, Report of the Second World Assembly on Aging; Madrid, Spain, United Nations. April 8–12, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veng LM, Browning MD. Regionally selective alterations in expression of the [alpha]1D subunit (Cav1.3) of L-type calcium channels in the hippocampus of aged rats. Mol Brain Res. 2002;107:120–127. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verkhratsky A, Toescu EC. Calcium and neuronal ageing. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:2–7. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villa A, Podini P, Panzeri MC, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Cytosolic Ca2+ binding proteins during rat brain ageing: loss of calbindin and calretinin in the hippocampus, with no change in the cerebellum. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:1491–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiong J, Camello PJ, Verkhratsky A, Toescu EC. Mitochondrial polarisation status and [Ca2+]i signalling in rat cerebellar granule neurones aged in vitro. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:349–359. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiong J, Verkhratsky A, Toescu EC. Changes in Mitochondrial Status Associated with Altered Ca2+ Homeostasis in Aged Cerebellar Granule Neurons in Brain Slices. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10761–10771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10761.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu A, Narayanan N. Effects of aging on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-cycling proteins and their phosphorylation in rat myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H2087–2094. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.6.H2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]