Abstract

Background

There is mixed evidence regarding the possible association between a history of stressful or traumatic life events and more rapid breast cancer progression.

Method

Retrospective reports of past experiences of traumatic life events were assessed among ninety-four women with metastatic or recurrent breast cancer. A traumatic event assessment was conducted using the event-screening question from the posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) module of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-TR (SCID; 2002). Each reported event was judged by two independent raters to determine whether it met DSM-IV-TR PTSD A1 criteria for a traumatic event. Those events that did not meet such criteria were designated “stressful events.”

Results

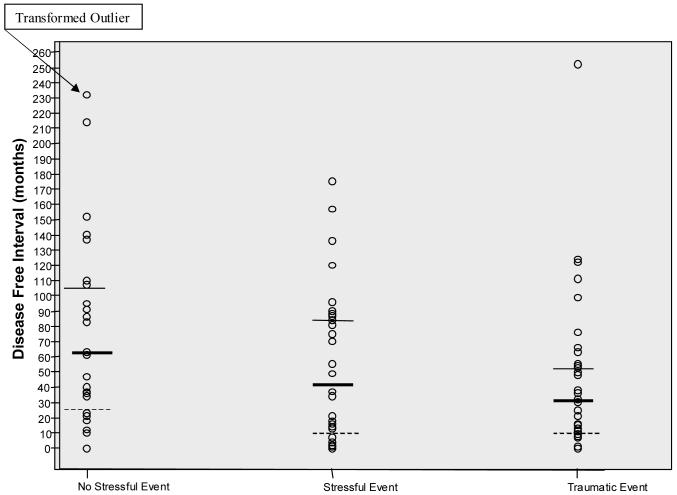

Nearly forty two percent of the women in the sample were judged to have experienced one or more traumatic events; 28.7% reported only stressful events. A Kruskal-Wallis test found significant differences in disease-free interval among the three groups χ2 (2, N = 94) = 6.09, p <.05. Planned comparisons revealed a significantly longer disease-free interval among women who had reported no traumatic or stressful life events (Median = 62 months) compared to those who had experienced one or more stressful or traumatic life events (Combined Median = 31 months).

Conclusions

A history of stressful or traumatic life events may reduce host resistance to tumor growth. These findings are consistent with a possible long-lasting effect of previous life stress on stress response systems such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

Keywords: traumatic events, stressful events, disease-free interval, metastatic breast cancer, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

Despite widespread public belief that stress can influence the incidence or progression of breast cancer, research findings have been inconsistent. Overall, tumor biology seems to dominate host resistance factors, stress-mediated or not. However, increasing evidence indicates adverse health effects of cumulative stressors and the body’s failure to adapt to them 1. Any prolonged exposure to stress produces an endocrine activation through the HPA axis which results in an increased production of cortisol. Increased production of cortisol diverts the body from its long-term needs (e.g. fighting infection) to focus on response to the threat via increased blood glucose. Indeed cortisol is powerfully immunosuppressive. The connection between trauma history and stress reactivity (measured as increased production of cortisol) was demonstrated by Heim and colleagues who found that an interaction between childhood abuse and adult trauma was the most powerful predictor of HPA responsiveness to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation (ACTH causes the adrenal cortex to release cortisol) and the Trier social stress task 2, 3. This neuroendocrine stress reactivity is exacerbated by additional trauma in adulthood.4 Dysregluation of HPA response has been shown to be related to breast cancer progression 5, 6.

Animal studies have shown that stress-induced elevations in cortisol caused by crowding are associated with far more rapid growth of implanted tumors, especially in older animals7, 8. There is also evidence that in humans changes in psychological state induced by stress can have an adverse effect on breast cancer incidence 9, 10 and relapse 11-13, although not all studies support this conclusion (e.g. 14, 15). Depression can be thought of as a state of maladaptive stress response and hypercortisolemia 16. A recent review found that 19 of 24 studies showed that depression, was associated with more rapid breast cancer progression 17.

Several studies have examined the relationship between the stressful life events and cancer progression. Graham and colleagues 18 found no relationship between stressful life events in the prior year and initial diagnosis, and stressful life events were weakly associated with a lower risk of relapse prospectively in 170 women with primary breast cancer. Stress was defined by the severity of the event, rather than by the individual’s reaction to that event. Similarly, Maunsell 19 found no relationship between reports, obtained three to six months after diagnosis, of stressful life events (weighted for emotional impact of the stressor) in the five years prior to diagnosis of breast cancer and subsequent mortality in a population of 673 patients.

In a study by Geyer9, 97 women with a breast lump who presented for a diagnosis were asked retrospectively about stressful life events they had experienced. Reported stressors were rated for severity using the Life Events and Difficulties Scale (LEDS; 20). The investigators found that reported severe life events were significantly more common among those who turned out to have a malignancy. These investigators replicated this finding in a second study that compared retrospectively reported life events among 33 women with cancer, 59 with a benign tumor, and 20 with gallstones. In the malignant group the rate of occurrence of the most severe stressful life events was four times higher than in the controls 10.

Lillberg and colleagues addressed the limitations of the previous two studies by conducting a much larger prospective Finnish cohort study (N = 10,808) and found no relationship between self-reported stress in a five-year period and subsequent diagnosis of breast cancer 21. However, these investigators found that major life events in the preceding five years were associated with elevated breast cancer risk, with a hazard ratio of 1.35 (95% CI: 1.09, 1.67)21. Indeed, divorce or separation was associated with a breast cancer incidence hazard ratio of 2.26 (95% CI: 1.25, 4.07), and death of a husband was associated with a similarly increased risk of breast cancer diagnosis (HR = 2.00, 95% CI: 1.03, 3.88). These findings remained significant even when controlling for age.

Intervention studies by Fawzy and Andersen in stress reduction and coping skills training provide further evidence for a stress-mediated impact on the immune system and potentially for cancer progression. Stress among women with breast cancer is related to the number and function of their natural killer cells 22, 23, 24. Fawzy et al observed that a brief intervention consisting of coping skills training was associated with improved survival 25. In the Fawzy study, participants in the active coping group had significantly great alpha interferon-augmented natural killer cell activity (NKCA) at six month follow-up than did controls, as hypothesized. However, this increase in NKCA was not associated with the longer survival observed in the treatment arm of this randomized prospective study. These studies provide further evidence linking stress and its treatment to endocrine and immune markers that affect cancer progression.

Although this literature is divided, it suggests that major stressors may be associated with an elevated risk of breast cancer incidence or relapse, indicating a role for stress response systems in somatic resistance to tumor progression 26, 27. In the present study we sought to test the hypothesis that retrospective reports of a history of highly stressful and/or traumatic life events would be associated with more rapid disease progression among women who have developed metastatic or recurrent breast cancer.

Method

Sample and Recruitment

Referrals for a study of stress and breast cancer were received from oncologists at Stanford University School of Medicine and around the San Francisco Bay Area, responses to newspaper advertisements, and word of mouth from study volunteers. Inclusion criteria included documented metastatic or recurrent breast cancer, a Karnofsky rating of at least 70%, residence within the Greater San Francisco Bay Area, and proficiency in English sufficient to enable answering questionnaires. Exclusion criteria included other active cancers within the past 10 years excepting basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas of the skin or in situ cancer of the cervix, positive supraclavicular lymph nodes as the only metastatic lesion at the time of initial diagnosis, a concurrent medical condition likely to influence short term survival, utilization of a corticosteroid within the preceding month, and a history of major psychiatric illness for which the patient was hospitalized or medicated, with the exception of depression or anxiety.

From a pool of 221 referrals, 21 failed to meet eligibility criteria, 83 were not interested in participating, and two died before they were able to enroll. After enrollment, four additional subjects were disqualified (one had two primaries, one had diabetes, another had two types of breast cancer but no recurrence, and the fourth was psychologically inappropriate). Of the remaining 111 participants, five were too busy to participate, one declined participation, one felt too ill, one had an accident, and three were excluded after reporting steroid medications in their baseline medication logs. Of the remaining one-hundred subjects, ninety-four had disease-free interval information and were used for the final analyses of the data. The demographic characteristics and medical status of the sample are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 99 Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer

| No Stress or Trauma History N=28 | Stressful Event History N=27 | Traumatic Event History N=39 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean± SD (range) | 56.43±11.19 (39-80) | 55.70±9.51 (41-74) | 52.97±8.71 (36-78) |

| Education, No. (%) | |||

| Trade or High School | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.7%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| Some College | 8 (28.6%) | 8 (29.6%) | 15 (38.5%) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 5 (17.9%) | 5 (18.5%) | 9 (23.1%) |

| Some Graduate School | 4 (14.3%) | 2 (7.4%) | 3 (7.3%) |

| Advanced Degree | 11 (39.2%) | 11 (40.7%) | 9 (23.0%) |

| Race, No. (%) | |||

| Asian | 4 (14.3%) | 2 (7.4%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| Black | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| American Indian | 1 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| White | 23 (82.1%) | 23 (85.2%) | 34 (87.2%) |

| Other/Unknown | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Ethnicity, No (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 2 (7.1%) | 2 (7.4%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| Marital Status, No (%) | |||

| Married | 22 (78.6%) | 16 (59.3%) | 27 (69.2%) |

| Never married | 3 (10.7%) | 1 (3.7%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| Divorced | 1 (3.6%) | 8 (29.66%) | 7 (17.9%) |

| Widowed | 2 (7.1%) | 2 (7.4%) | 2 (5.1%) |

| Household Income, No (%), $ | |||

| < 20,000 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (15.0%) |

| 20,000-39,999 | 7 (24.1%) | 6 (22.2%) | 4 (10.0%) |

| 40,000-59,999 | 2 (6.9%) | 4 (14.8%) | 5 (15.0%) |

| 60,000-79,999 | 4 (13.8%) | 3 (11.1%) | 10 (25.0%) |

| 80,000-99,999 | 3 (10.3%) | 5 (18.5%) | 3 (7.5%) |

| ≥ 100,000 | 10 (34.5%) | 7 (25.9%) | 9 (22.5%) |

| Don’t know/not reported | 4 (14.3%) | 2 (7.4%) | 2 (5.0%) |

Table 2.

Medical Variables

| No Stress Trauma History (N=28) | Stressful Event History (N=27) | Traumatic Event History (N=39) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at initial diagnosis, mean ± SD (range), years | 47.25 ±9.77 (29-75) | 49.11±10.10 (30-71) | 46.64±8.70 (32-73) |

| Estrogen receptor negative, No. (%) | 8 (28.6%) | 8 (29.6%) | 11 (28.9%) |

| Progesterone receptor negative, No. (%) | 11 (39.3%) | 8 (30.8%) | 9 (25.0%) |

| Dominant site of metastasis at study entry, No. (%) | |||

| Bone | 8 (28.6%) | 4 (14.8%) | 10 (25.6%) |

| Chest | 8 (28.6%) | 8 (29.6%) | 17 (43.6%) |

| Viscera | 12 (42.9%) | 15 (55.6%) | 12 (30.8%) |

| Diurnal cortisol log slope, mean ± SD (range) | -.16±.06 (-.28 to -.04) | -.16±.07 (-.31 to -.01) | -.15±.07 (-.29 to .07) |

| Cortisol AM, mean± SD (range) | .59±.33 (.20 to 1.85) | .58± .26 (.04 to 1.18) | .54±.21 (.04 to 1.06) |

| Cortisol AM+30 min., mean± SD (range) | .12±.34 (-.40 to .91) | .36±.33 (-.05 to 1.25) | .23±.38 (-.67 to 1.05) |

Measures

Assessment of Demographic and Medical Status Variables

Estrogen/progesterone receptor status, degree and type of metastatic spread—to soft tissue, lymph nodes, bone, or viscera (liver, brain, pleura, lung, or other organs)—and age at disease diagnosis were abstracted from patients’ medical records. Information on participants’ age, race, income, education, and marital status was collected through self-report questionnaires. Patients’ disease-free interval was calculated as time from initial diagnosis to date of diagnosis of recurrence or metastasis. Depression symptoms were assessed by using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II 28).

Cortisol Assessment

Salivary cortisol has been found to be a reliable measure of HPA activity 29. The participants collected salivary samples over the course of two days five times day at their homes (at waking, 30 minutes later, at noon, 5pm, and 9pm). This protocol has been used in other studies 29, 30. The collection of waking and 30 minutes post waking cortisol was added to examine normal morning HPA activation 29.

Assessment of Traumatic Life Events

Traumatic event history was assessed for each study participant using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR 31. The SCID is a semi-structured clinical interview that yields reliable DSM psychiatric diagnoses 10, 32. As part of the baseline assessment, trained interviewers administered a modified version of the SCID (the modules for mood episodes and disorders, substance-use disorders, the psychotic screen, and the posttraumatic stress disorder screen were administered) to participants in order to examine exclusion criteria with respect to psychiatric history. This assessment included the traumatic event screening query from the PTSD module that seeks to determine whether respondents have experienced events that may qualify for the PTSD A1 event exposure criterion. The query asks respondents whether they have ever experienced “extremely upsetting” events such as an accident, fire, assault, rape, seeing another person killed or badly injured, or hearing that something horrible happened to a loved one. Interviewers recorded a brief description of each event that was reported and the date and age at which it happened.

Coding Stressful and Traumatic Events

To determine whether the reported events met DSM-IV-TR PTSD A1 objective traumatic event exposure criteria, each reported event was judged by two independent raters with expertise in traumatic stress (DS and LDB), with no access to disease status information. Judge determinations of whether the event is stressful or traumatic were made based on the DSM-IV-TR (2000) PTSD A1 traumatic event exposure criterion that requires that the “person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others” (p.427). Criterion A1 only includes events that are deemed traumatic according to the DSM-IV-TR and would not include recreational activities (unless there was an accident). The category to which the event was assigned was based on the description of the experience provided by the subject (and recorded on the SCID), rather than simply the type of event involved. These descriptions sometimes included information about the level of personal exposure and life threat that indicated the seriousness of the event.

Events were coded separately and participants were given an overall life event code that reflected the highest level of event exposure they had reported across events. Overall life event coding designations included “none,” where participants did not report any experiences in response to the prompt; “stressful,” when participants reported only events that were judged not to meet DSM-IV-TR A1 criteria for PTSD; or “traumatic,” when one or more reported events was judged to qualify as a PTSD A1 traumatic event.

Examples of events that were judged “traumatic” included a history of childhood sexual abuse, rape, “mother’s throat cut open falling on bottle”, “sexual experiences that felt like rape”, “sexually abused by priest - fondled”, “sexual assault during marriage”, “daughter assaulted”, and “father suicide”. Examples of events that were coded “stressful” included “father died of cancer”, “adoption”, “family member in jail”, “father leaving family”, “grandson walked out of house as a child”, “earthquake”, and “immigrating to the US”, “living with mother-in-law for several years”, “parents divorcing.”

Interrater Coding Reliability

Agreement between coders was calculated based on both coders’ ratings of participants’ reported experiences of highly stressful or traumatic life events, using the kappa statistic to correct for chance. Overall, coders reliably identified women who reported no stressful or traumatic event (kappa = 1.00), women who reported one or more stressful life events but no traumatic life events (kappa = .67), and those who had experienced at least one traumatic event (kappa = .71). After ratings were made independently, the coders met with the third coder (OP) and resolved the coding discrepancies. Final decisions about coding disagreements were made by the third coder (OP) during discussion with the other two coders.

Data Analysis

Because the distribution of the disease progression variable was positively skewed, an omnibus Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized with three levels of life experiences (no stressful or traumatic life event, stressful but not traumatic life events, and traumatic life events). Mann-Whitney tests were conducted for planned comparisons. For each such test, effect sizes are presented to facilitate interpretation of the clinical significance of the result. Consistent with the non-parameteric tests, we present Area Under the Curve (AUC), which estimates the probability that a patient in one of two groups being compared has an event-free interval longer than in the other 33-37. In turn, NNT (Number Needed to Take), an effect size favored in Evidence Based Medicine, 36, 38-40 equals 1/(2AUC-1). NNT is the number of subjects one would need to take from the better outcome group to have one more “success” than if the same number had been taken from the poorer outcome group. Ideally, we want AUC to be as near to 100% as possible, and NNT to be as near to 1 as possible. In this case NNT represents the number of subjects in Chi-square analysis and one-way analysis of variance who were used to examine differences between the three life event groups on demographic and medical variables to determine whether differences associated with the life event variable should be controlled for in analysis.

Results

Experience of Stressful and Traumatic Events

About a third of the women (29.8%) in the sample reported no stressful or traumatic life events exclusive of their experiences with breast cancer. Of the remaining 70.2%, 19% reported having experienced rape, assault, or childhood abuse; 16% had survived a life-threatening accident (car, boat, or drowning); 4 % had experienced a natural disaster; 9% reported witnessing traumatic events (murder, injury or crime) or death due to illness; 26% reported the death of loved ones due to injury or illness; 3% reported the death of their child; and 14% reported a life threat to one or more loved ones due to injury or illness. These events were coded as either stressful or traumatic events; 28.7% of the sample reported only stressful life events, and 41.5 % of the sample reported one or more traumatic life events that met the DSM-IV-TR A1 diagnostic criterion for PTSD.

Disease-Free Interval

Past experience of stressful or traumatic life events was associated with the length of the disease-free interval in women with metastatic breast cancer. A Kruskal-Wallis test found significant differences among the three groups χ2 (2, N = 94) =6.09, p = .047. As seen in Figure 1, women who reported a history of traumatic life events had the shortest disease-free interval (Median = 30 months, Range 0-252 months), followed by women with a history of stressful life events (Median = 37, Range 0-175 months), followed by women with no such histories (Median = 62, Range 0-471 months). In Figure 1, it should be noted that one severe outlier in the “no stress” group (DFI = 471 months) was transformed and included in the graph.

Figure 1.

Disease-Free Interval by Type of Event (Median, 25th and 75th Percentiles)

Planned Comparisons

Planned comparisons did not yield a statistically significant difference in disease-free interval between those who had experienced traumatic life events and those who had experienced only stressful life events (z = -.76, ns; AUC =55 %; NNT = 10). However, the pooled group including those who reported either or both traumatic and stressful life events showed a significantly shorter disease-free interval when compared to the group who had not experienced any such events (z = -2.35, p = .02; AUC =65 %; NNT = 3.33 ). Nonparametric tests and statistics were used for the analyses because the distributions violated parametric assumptions. When we excluded participants whose traumatic and stressful events occurred after their initial diagnosis of cancer, we again found significant differences among groups χ2 (2, N =83) = 7.01, p = .03.

Tables 1 and 2 show the descriptive statistics for each of the three groups. No significant differences among groups were found on current age, age at time of diagnosis, estrogen or progesterone receptor status, medical history, site of metastasis, diurnal cortisol or waking cortisol, or relationship status. There was no significant relationship between depression symptoms and disease-free interval (r = .02, ns)

Discussion

This study provides further evidence that a history of stressful or traumatic life events is associated with a shorter disease-free interval, indicating a potential effect of these experiences on host resistance to tumor growth. One possible mechanism linking a history of stressful or traumatic experiences and more rapid breast cancer progression is the effect of such stress on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function. The long-term effects of stress on HPA axis function have been convincingly demonstrated in rodents in relation to maternal licking and grooming behavior in response to handling 41. In humans, Heim and colleagues 42-44 have shown HPA hyperactivation in response to stress among women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. The salience of such long-term HPA hypersensitivity to cancer is indicated by evidence that dysregulation of the diurnal pattern of cortisol predicts significantly earlier mortality among women with metastatic breast cancer 5.

However, in our study we found no statistically significant differences between cortisol levels and stress/trauma history. One potential explanation for this finding was proposed by Abercrombie and colleagues 45 and Spiegel and colleagues 46. Both studies found that women with metastatic breast cancer had “flattened” or lower cortisol levels than healthy controls, suggesting the that the physiology of metastatic breast cancer might have incremented any potential variability in cortisol itself that is usually present in healthy people and even in people with less severe cancer disease (e.g. primary breast cancer). These findings support the disrupted feedback inhibition model of response to stress rather than hypersensitivity as previously believed.

Limitations of the present study include the modest sample size and the retrospective nature of patients’ reports of life experiences. It is possible that women with more serious disease, evidenced by more rapid disease progression, were biased in their reports of previous adverse life events in the direction of being more or less likely to remember and/or report such events. However, we found no relationship between reporting depressive symptoms and disease-free interval in this sample. Also, the sample was drawn from women interested in a study on stress and breast cancer, which could have introduced bias into the overall sample toward those with a more stressful life history, although this would not have influenced within-group relationships between stress history and disease progression. All of the women in the study had metastatic disease or recurrent cancer, and therefore none was free of anxiety about disease progression and eventual mortality.

It should be noted that we studied reports of stressful and traumatic events themselves, rather than the degree of subjective reaction to the stressors or participants’ means of coping with them. Another limitation of this research is the low inter-rater reliability between trauma experts in coding stressful and traumatic events. Although we attempted to resolve these inconsistencies by employing a third coder, this lack of agreement between trauma experts on definition of “stressful” vs.” highly stressful” and “traumatic” is a definite limitation of this and of other similar type of research. In spite of somewhat lower inter-rater agreement, we were still able to find evidence that there is a significant positive association between experiencing and reporting a stressful or traumatic event and disease-free interval in women with metastatic breast cancer. Random error would limit our ability to detect other associations, but the pattern of results suggested a continuum between non-stressful events, stressful events, and traumatic stressors.

Indeed, we found in a related study of this population that patients classified by clinicians as depressed either by SCID interview or a medical prescription for antidepressant medication had a shorter disease-free interval than those without depression 47. This methodology as well as that used in the current study involves reports of events or an external evaluation of patient status rather than subjective report of mood status, which may explain the lack of relationship between scores on the BDI and disease-free interval. In future studies it would be important to separately analyze the severity of stressful or traumatic events and patients’ subjective experiences such as presence or absence of fear. Modern theories of PTSD emphasize the importance of “criterion A trauma,” meaning fear, horror, and hopelessness during the traumatic experience. It would be important for future research to examine subjective markers of distress in combination with severity and perhaps make distinction between fear-inducing trauma versus trauma that is upsetting and/or anger-producing, but not fear-inducing.

This study contributes to the literature suggesting that the experience of stressful or traumatic life events may contribute to the progression of breast cancer. It may be fruitful for future research to examine prospectively larger numbers of women with breast cancer and assess, in addition to stressful and traumatic life events, other indices of the HPA and other endocrine, immune, and autonomic nervous system responses to stress. This body of research may lead to a new understanding of psychosocial risk factors for disease progression and may result in novel interventions designed to buffer the adverse effects of earlier stressful or traumatic life events on the hyperactivation of the HPA axis and potentially ameliorate the impact of previous trauma and subsequent development and progression of cancer.

Acknowledgements

We thank Helena C. Kraemer for consultation on data analyses, Eric Neri and Mark Rothkopf for data management, and Bita Nouriani and Manijeh Parineh for data collection.

Supported by Program Project Grant P1AG18784 to David Spiegel, MD from the National Institute on Aging and the National Cancer Institute

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338(3):171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heim C, Newport DJ, Graham YP, et al. Pituitary-Adrenal and Autonomic Responses to Stress in Women After Sexual and Physical Abuse in Childhood. JAMA. 2000;284:592–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heim C, Newport DJ, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. Long-term neuroendocrine effects of childhood maltreatment. JAMA. 2000 Nov 8;284(18):2321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heim C, Newport DJ, Wagner D, Wilcox MM, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. The role of early adverse experience and adulthood stress in the prediction of neuroendocrine stress reactivity in women: A multiple regression analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2002;15(3):117–125. doi: 10.1002/da.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Diurnal Cortisol Rhythm as a Predictor of Breast Cancer Survival. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:994–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sephton S, Spiegel D. Circadian Disruption in Cancer: A neuroendocrine-immune pathway from stress to disease? Brain, Behavior and Immunity. 2003;17(5):321–328. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(03)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riley V. Psychoneuroendocrine influences on immunocompetence and neoplasia. Science. 1981;212(4499):1100–1109. doi: 10.1126/science.7233204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sapolsky RM, Donnelly TM. Vulnerability to stress-induced tumor growth increases with age in rats: role of glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 1985;117(2):662–666. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-2-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geyer S. Life events prior to manifestation of breast cancer: a limited prospective study covering eight years before diagnosis. J Psychosom Res. 1991;35(23):355–363. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(91)90090-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geyer S. Life events, chronic difficulties and vulnerability factors preceding breast cancer [see comments] Soc Sci Med. 1993;37(12):1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90189-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramirez AJ, Craig TK, Watson JP, Fentiman IS, North WR, Rubens RD. Stress and relapse of breast cancer [see comments] British Medical Journal. 1989;298(6669):291–293. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6669.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forsen A. Psychosocial stress as a risk for breast cancer. Psychotherapy Psychosomatics. 1991;55(24):176–185. doi: 10.1159/000288427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsen A. Stress and personality as risk factors in breast cancer (editorial) Duodecim. 1990;106(16):1129–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barraclough J, Pinder P, Cruddas M, Osmond C, Taylor I, Perry M. Life events and breast cancer prognosis [see comments] British Medical Journal. 1992;304(6834):1078–1081. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6834.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barraclough J, Osmond C, Taylor I, Perry M, Collins P. Life events and breast cancer prognosis [letter; comment] British Medical Journal. 1993;307(6899):325. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6899.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold PW, Goodwin FK, Chrousos GP. Clinical and biochemical manifestations of depression. Relation to the neurobiology of stress (2) N Engl J Med. 1988;319(7):413–420. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198808183190706. [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 1988 Nov 24;319(21):1428] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J. Depression and Cancer: Mechanisms and Disease Progression. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):269–282. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham J, Ramirez A, Love SB, Richards M, Burgess C. Stressful life experiences and risk of relapse of breast cancer: Observational cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2002;324(14201422) doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maunsell E, Brisson J, Mondor M, Verreault R, Deschcnes L. Stressful life events and survival after breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 2001 Mar-Apr;63(2):306–315. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown G, Harris T. The Bedford College Life-Events and Difficulty. Bedford College, University of London; London, England: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lillberg K, Verkasalo PK, Kaprio J, Teppo L, Helenius H, Koskenvuo M. Stressful life events and risk of breast cancer in 10,808 women: a cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 Mar;157(5):415–423. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz D, et al. Stress and immune responses after surgical treatment for regional breast cancer [see comments] J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(1):30–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen BL, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. A biobehavioral model of cancer stress and disease course. Am Psychol. 1994;49(5):389–404. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.5.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fawzy FI, Kemeny ME, Fawzy NW, et al. A structured psychiatric intervention for cancer patients. II. Changes over time in immunological measures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(8):729–735. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810200037005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fawzy FI, Canada AL, Fawzy NW. Malignant melanoma: effects of a brief, structured psychiatric intervention on survival and recurrence at 10-year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 Jan;60(1):100–103. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Early mortality in metastatic breast cancer patients with absent or abnormal diurnal cortisol rhythms. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(12):994–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heim C, Ehlert U, Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck AT. Depression Inventory. Center for Cognitive Therapy; Philadelphia: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer D. Salivary cortisol in psychobiological research: An overview. Neuropsychobiology. 1989;22(3):150–169. doi: 10.1159/000118611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sephton SE, Dhabhar FS, Classen C, Spiegel D. The diurnal cortisol slope as a predictor of immune reactivity to interpersonal stress. Brain, Behavior & Immunity. 2000;14(2):128. [Google Scholar]

- 31.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zanarini M, Skodol AE, Bender DS, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, Morey LC, Grilo CM, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of Axis I and II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraemer HC, Morgan G, Leech NL, Gliner JA, Vaske JJ, Harmon RJ. Measures of clinical significance. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003 doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grissom R. Probability of the superior outcome of one treatment over another. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1994;79(3):14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(11):990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGraw KO, Wong SP. A common language effect size statistics. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111(361):361–365. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altman DG, Andersen PK. Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1492–1495. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: A clinically useful measure of treatment effect. British Medical Journal. 1995;310:452–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grissom R, Kim JJ. Effect Sizes for Research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, New Jersey: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fish EW, Shahrokh D, Bagot R, et al. Epigenetic programming of stress responses through variations in maternal care. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1036:167–180. doi: 10.1196/annals.1330.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penza K, Heim C, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiological effects of childhood abuse: implications for the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety. Arch Women Mental Health. 2003;6(1):15–22. doi: 10.1007/s00737-002-0159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, Bonsall R, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA. 2000;2(284):592–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heim C, Ehlert U, Hanker J, Hellhammer DH. Abuse-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Alterations of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in Women With Chronic Pelvic Pain. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60(3):309–318. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abercrombie HC, Giese-Davis J, Sephton S, Epel ES, Turner-Cobb JM, Spiegel D. Flattened Cortisol Rhythms in Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1082–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J, Taylor CB, Kraemer H. Stress sensitivity in metastatic breast cancer: Analysis of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(10):1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giese-Davis J, Wilhelm F, Conrad A, et al. Depression and Stress Reactivity in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:675–683. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000238216.88515.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]