Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To provide a rapid and efficient means of collecting descriptive epidemiological data on occurrences of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) in Canada.

DESIGN AND METHODS:

Passive reporting of data on individual or cluster occurrences of VRE using a one-page surveillance form.

SETTING:

The surveillance form was periodically distributed to all Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee members, Community and Hospital Infection Control Association members, L'Association des professionnels pour la prevention des infections members and provincial laboratories, representing 650 health care facilities across Canada.

PATIENTS:

Patients colonized or infected with VRE within Canadian health care facilities.

RESULTS:

Until the end of 1998, 263 reports of VRE were received from 113 health care facilities in 10 provinces, comprising a total of 1315 cases of VRE, with 1246 cases colonized (94.7%), 61 infected (4.6%)and eight of unknown status. (0.6%). VRE occurrences were reported in 56% of acute care teaching facilities and 38% of acute care community facilities. All facilities of more than 800 beds reported VRE occurences compared with only 10% of facilities with less than 200 beds (r2=0.86). Medical and surgical wards accounted for 51.4% of the reported VRE occurences. Sixty-five (24.7%) reports indicated an index case was from a foreign country, with 85.2% from the United States and 14.8% from other countries. Some type of screening was conducted in 50% of the sites.

CONCLUSIONS:

A VRE passive reporting network provided a rapid and efficient means of providing data on the evolving epidemiology of VRE in Canada.

Key Words: Epidemiology, Surveillance, Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus

Originally classified as Lancefield group D streptococcus, enterococcus was appropriately classified into its own genus in the 1980s, based on DNA-DNA hybridization studies (1). For many years enterococci were viewed as organisms of low virulence, with little potential for human infection. In recent years, enterococci and notably vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE) have been recognized as increasingly important nosocomial pathogens, and enterococci are now the second most commonly isolated nosocomial pathogens and the third most common pathogen associated with nosocomial bacteremia in the United States (2-4). The National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance (NNIS) System in the United States reported a 20-fold increase in the percentage of nosocomial enterococcal isolates resistant to vancomycin between 1989 and 1993 (3). Between 1989 and 1997, the percentage of enterococci isolated from nosocomial infections in intensive care unit (ICU) patients that were resistant to vancomycin rose from 0.4% to 23.2% and in non-ICU patients from 0.3% to 15.4% (5). From January to December 1999, VRE accounted for 25.2% of enterococci associated with nosocomial infections in ICU patients participating in the NNIS, a 43% increase in resistance over the previous five years (6). Initially found in large hospitals, VRE now can be found in America hospitals of all sizes (5). The demonstration of conjugative transfer of high-level vancomycin resistance from Enterococcus faecalis to Staphylococcus aureus (7) and the appearance of S aureus with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides (glycopeptide intermediate S aureus) in the United States and Japan (8,9) have heightened concerns over VRE.

The first isolate of VRE in Canada was reported in Edmonton in 1993 (10) and the first published outbreak of VRE in Canada occurred in Toronto in 1995 (11). Since then, additional outbreaks and occurrences of VRE have been identified in Canada in both acute and long term care facilities (12-20). In response to the need for more data describing the epidemiology of VRE in Canada, the VRE Working Group of the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP), a collaborative effort of the Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee (CHEC), a subcommittee of the Canadian Infectious Disease Society, and the Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, Population and Public Health Branch, Health Canada (formerly the Laboratory Centre for Disease Control) undertook several initiatives, including two point-revalence surveys (15, unpublished data) and the establishment of a Passive Reporting Network (PRN) for VRE occurrences in Canada.

BACKGROUND

Two surveys conducted by CNISP in 1996 and 1997 identified VRE in several CHEC affiliated hospitals (15, unpublished data). The 21 participating health care facilities included both paediatric and adult tertiary care teaching hospitals and represented over 80% of the medical school affiliated institutions in Canada. The first survey included 26 Canadian hospitals participating in the CNISP 1996 VRE point prevalence survey (15). A total of 3773 patients were enrolled, and stool or rectal swabs were collected from 'high-risk' patients, including patients receiving dialysis, and inpatients on hematology-oncology wards, solid organ transplant wards, bone marrow transplant units and ICUs. VRE was isolated from 26 patients (25 colonized and one infected), of whom one was from Alberta and 25 were from Ontario. One Ontario hospital had 25 of the 26 VRE positive patients identified, but this institution had an outbreak within its renal dialysis population three months before this survey (10). The prevalence rate was 0.1% for high risk patients in a nonoutbreak hospital, 3.7% for high risk patients in an outbreak hospital and 5.3% in the outbreak patient group (dialysis) within the outbreak hospital.

The second survey, conducted in 1997 (unpublished data), included 19 CHEC affiliated hospitals with 2264 'high risk' patients screened. Four cases (0.18%) of VRE colonization were identified. Two cases were from Ontario and two from Alberta, with two cases in dialysis patients and two cases in hematology-oncology patients. Given this background and the results of the two CNISP VRE point prevalence surveys, a 'VRE Occurrence Report' form was developed by the VRE Working Group to facilitate rapid data collection using a passive reporting system.

DATA AND METHODS

The VRE occurrence report form was designed to collect information on the frequency and location of VRE occurrences, services and screening patterns of health care facilities that identified VRE cases. Because the form captured all VRE occurrences and not just those in 'high risk' patients, more comprehensive reporting would be achieved. The form was sent to all CHEC members, Community and Hospital Infection Control Association (CHICA) members, l'Association des Professionnels pour la Prevention des Infections (APPI) members and provincial laboratories. Only one form was to be completed per health care facility. The form was completed for individual or clusters of VRE cases and returned to the Division of Nosocomial and Occupational Infections, Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control by mail or by fax for purposes of collation and analysis. Clusters were defined as follows: more than one case occurring within the same patient group (eg, dialysis, bone marrow transplant patients), or same unit or ward (eg, neonatal ICU, medical ICU, haematology-oncology ward) where each additional case was identified no more than one month after the previous case; the strain of VRE had been linked via molecular-typing methods to another case within the same hospital (time was not a factor); a new case was identified and known to have had contact with another previously identified case. A single occurrence report form could have one or multiple VRE cases.

The VRE occurrence report form collected information on the following major themes:

setting - type and location of health care facility and service

investigation - date, laboratory methods, case finding, number of cases, colonization and/or infection status and screening status; and

modes of transmission (based on best judgement) - patient-to-patient, staff and environmental

Data up until the end of 1998 were checked for duplicate reporting, entered and analyzed using Epi Info (version 6.04, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA). In the latter part of 1998, a prospective surveillance program for VRE was established within CHEC participating facilities supplanting the VRE PRN. Total numbers of enterococci isolated in the clinical laboratory were available for each of the CHEC site hospitals between 1995 and 1998 (15). Linear regression was used on dependent variables as appropriate.

RESULTS

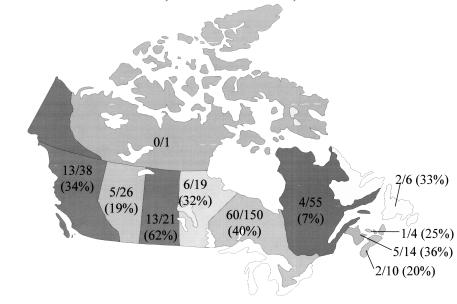

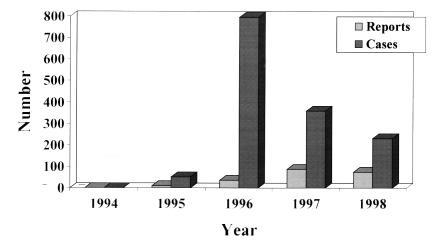

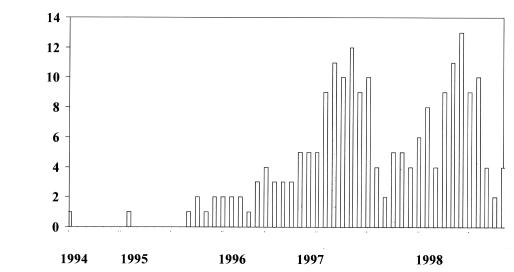

The distribution system for the PRN represented approximately 650 health care facilities (63% of all health care facilities in Canada), and responses indicating the presence of VRE were reported by 53% of those facilities. Until the end of 1998, 263 reports of VRE were received from 113 health care facilities in 10 provinces (Figure 1), comprising 1315 cases of VRE with 1246 cases colonized (94.7%), 61 infected (4.6%) and eight (0.6%) either unknown or not recorded. The number of reports (with the initial date of investigation as the date indicator) increased from one in 1994 to 103 in 1998 (Figure 2), but remained relatively constant during 1997 and 1998 (Figure 3). The number of cases, however, peaked in 1996 due to an outbreak in one centre, which identified 450 cases.

Figure 1.

Number of participating Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci Passive Reporting Network health care facilities reporting occurrences of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus across Canada, June 1, 1994 to December 31, 1998

Figure 2.

Number of reports and cases of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus per year from June 1994 to December 1998, Canadian Nosocomial Infections Surveillance Program Vancomycin-resistant Passive Reporting Network

Figure 3.

Number of reports of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus by date of initial investigation, June 1994 to December 1998, Canadian Nosocomial Infections Surveillance Program Vancomycin-resistant Passive Reporting Network

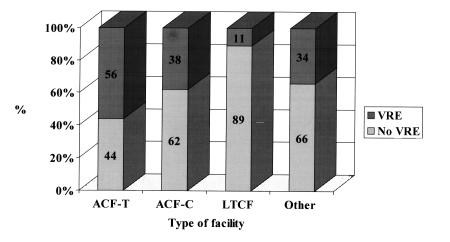

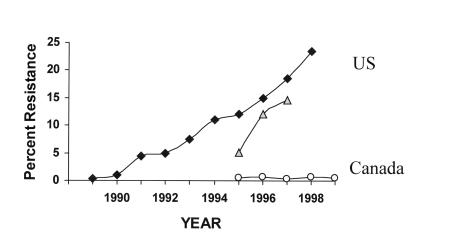

Acute care facilities, both teaching and community, accounted for the majority of the total number of reports received, with VRE reported in 56% of acute care teaching facilities and in 38% of acute care community facilities (Figure 4). The greater the number of beds within a facility, the greater the percentage of VRE reports, with all facilities of more than 800 beds reporting VRE compared with only 10% of facilities with less than 200 beds (r2=0.86). The types of service and relative frequencies at which VRE was reported included the following: medical wards (37.2%), surgical wards (14.2%), ICUs (13.2%), chronic care wards (7.4%), dialysis units (4.8%) ,and other (21.2%). Of the total reports, 66% identified only one VRE case. Extracting data on enterococci with resistance to vancomycin from the CHEC sites within the VRE PRN and using annual denominator data on the total number of enterococcal laboratory isolates from these sites provided annual rates of VRE among all enterococcal isolates that allowed comparison with similar data from the NNIS and other surveillance systems (5,21,22) in the United States (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Frequency (%) of reports of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus by type of facility, the Canadian Nosocomial Infections Surveillance Program Vancomycin-resistant Passive Reporting Network. ACF-T Acute care facility - Teaching; ACF-C Acute care facility - Community; LTCF Long term care facility; Other Paediatric or psychiatric facility

Figure 5.

Vancomycin resistance among enterococci in Canada versus the United States. ▪ 1995 to 1999 Percentage vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in all enterococcal isolates in Canada. ♦ 1989 to 1998 Percentage VRE in all enterococcal isolates in United States. ▴ 1995 to 1997 Percentage VRE in all enterococcal isolates in the United States. Data adapted from references 5, 21 and 36, the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program VRE Passive Reporting Network (Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee sites only) and VRE incidence Surveillance Program data (Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee sites only), 1994 to 1998 and 1999, respectively

The 113 health care facilities screened 25,276 patients, with a mean of 97 patients (median of 10; range of 0 to 1000) per facility. Sixty-one per cent of the health care facilities reporting a case of VRE screened at least one person, and 39% did not perform any screening. Of those facilities participating in the survey, 50% reported performing some form of admission screening. In facilities that screened after a patient was identified, 687 colonized and 12 infected VRE cases (these included 10 with urine cultures positive for VRE) were identified. Of those facilities that had VRE cases and performed screening, 46% found an additional case. Six health care facilities screened 217 staff members, and no VRE carriage was detected among this group. Sixty-five (24.7%) reports stated the index case was from a foreign country, with 85.2% from the United States and 14.8% from other countries. The identification of the first case or the first case within a cluster was primarily found through admission screening (72.4%), followed by 17.2% clinical indication and 10.4% other means (Clostridium difficile stool or urine screening).

Culture of the enviromnent and equipment within the facilities was recorded in 43.6% of the reports, with 28% finding positive cultures. Cultures positive for VRE were reported from shared equipment, mattresses, call bells, narcotic cupboard keys, walls, housekeeping carts, commodes, intravenous pumps, toilets, soap dispensers, floors, bed rails, chair seats, medication charts, bedside tables, telephones, television screens, stethoscopes, keyboards and a door knob.

DISCUSSION

The results of the CNISP VRE-PRN revealed that the burden of VRE in Canadian health care facilities was greater and more widespread than suspected, based on the previous point-prevalence surveys (15, unpublished data). VRE was occurring not only in high risk populations (22) but also on general medical and surgical wards, in paediatric facilities and in long term care centres. The VRE PRN provided valuable information on the geographical distribution and chronological events surrounding the introduction and dissemination of VRE within Canada. It also identified the first report of a cluster of VRE patients occurring as early as 1994 rather than in 1995 as the first published VRE outbreak reported (11). Similar to the experience in the United States, the majority of reports of VRE cases in Canada occurred in acute care facilities (5). There was a high correlation between the number of beds within a facility and the likelihood of identifying VRE.

The VRE PRN illustrated the extensive screening occurring throughout Canadian health care facilities, explaining the large number of colonized patients (94.7%) identified. The ratio of colonized to infected patients did not significantly change from year to year, which suggests that no large increases in the rates of VRE infected cases were occurring over time. The actual number of infected patients (n=61) over the five years of surveillance may be even lower given the difficulty in interpreting whether patients with indwelling urinary bladder catheters have asymptomatic bacteriuria or invasive bladder infections. Approximately 25% of the index cases for each cluster originated from a foreign country, usually the United States, suggesting that VRE may be an imported microorganism. The latter is an important observation for Canadian centres that are designing screening programs for early detection of VRE. Of the VRE cases reported in the PRN, 41% were identified through admission screening. The observation that VRE carriage was not detected in 217 exposed health care workers proved to be quite valuable because many centres were uncertain of the likelihood of transmission to health care workers in the setting of a VRE cluster.

Although almost 95% of all VRE cases found in the PRN in Canada represented colonization, the finding of VRE infections in 4.6% of the cases is not without concern (23). In the American NNIS system, 25% of all enterococcal infections have become resistant to vancomycin over a 10-year period (3,5,21), and during 1996 and 1997, in the project Intensive Care Antimicrobial Resistance Epidemiology (ICARE), 10% of all enterococci isolated from participating hospitals were resistant to vancomycin. It will be interesting to see whether the percentage of VRE (taken as a proportion of all enterococcal infections) increases over time in Canada as it has in the United States. In addition to the usual high-risk patient groups, such as dialysis, oncology, transplantation and critical care patients (22), VRE cases have been increasingly reported in other groups of patients in the United States, including those in or using long term care, outpatient clinics, outpatient dialysis centres and neonatal units (24-27). Dialysis patients, however, remain a group with increased rates of VRE colonization, with prevalence rates ranging from 9.2% to 23% within several dialysis centres in the United States (26,27). These latter patient groups were not noted in the PRN.

In Europe, colonization rates in hospitalized patients range from 1.8% to 5% (28)(32), and as high as 15% among dialysis patients (31) and 16.3% in ICU patients (32). In contrast to the relatively low rates of VRE colonization in European inpatients, higher rates (0.9% to 12%) are found in outpatients and community-based volunteers (5,28,32). These latter findings differ from the United States where no VRE was found within community-based individuals (33,34). It has been suggested that the frequent occurrence of VRE in the stools of nonhospitalized community patients in several European countries may be due to its acquisition via the food chain (5,28). Enterococcus faecium resistance has been associated with the use of the glycopeptide avoparcin used as a growth promoter and the presence of VRE in fecal samples collected from flocks (34). The difference between Europe and the United States in the frequency of VRE as a cause of nosocomial enterococcal infections is dramatic (28). Data on the frequency of nosocomial enterococcal infections were not collected in the PRN. However, in the CHEC sites within the PRN, between three and 12 clinical isolates of VRE were identified per year between 1995 and 1998, with no evidence for any yearly increase in absolute numbers or rates. The annual rate of VRE occurrence described within the CHEC sites also did not change, remaining consistently less than 1% of all enterococci during the study period. In addition, the CNISP VRE Incidence Surveillance Program, which began in the last quarter of 1998 and included only the sentinel CHEC health care facilities, reported 95 isolates (eight from clinical specimens) of VRE to the end of 1999, representing a rate of 0.19/1000 patient admissions and 0.55% of all enterococcal isolates from the participating facilities (36), which corroborates the observations in the PRN.

The information gained through the CNISP VRE surveillance projects suggests that the epidemiology of VRE in Canada is similar to that of Europe and differs considerably from that of the United States. Although caution must be exercised in the interpretation of the data, it seems apparent that the rate and increase of nosocomial VRE infections is quite different from the American experience. However in contradistinction to the European experience, our community population would not have been exposed to poultry that had been contaminated with VRE because avoparcin and other glycopeptide agents have not been used as growth promoters in the agrifood sector in Canada. In addition to differences in the rates of VRE colonization and infection between Europe, Canada and the United States, there are differences in the relative frequency of E faecalis and E faecium as causes of enterococcal infection. While E faecium infections have become increasingly more common in the United States, they remain relatively infrequent in Canada and Europe (20,29,30).

Despite the close physical proximity of Canada to the United States, VRE has not attained the same colonization rate and are rarely encountered as a cause of infection in Canada. The reasons for this are complex and likely related to multiple factors including the frequency of usage of antimicrobial agents, differences in the use of broad spectrum agents, differences in infection control practices, the presence of reservoirs of VRE in the population and differences in health care delivery systems.

Although valuable information was gained from the VRE PRN, there are several limitations in the use and interpretation of the data collected. Because this was a passive reporting system, all cases or clusters of VRE may not have been reported. However, the group to which the forms were distributed are very dedicated professionals who were, therefore, likely to reporta VRE occurrences. The VRE occurrence report form did not have strict definitions for the information collected, and differences in interpretation may have occurred by those completing the form. The data collected also had the potential for duplicate reporting, although efforts were made to eliminate this. A single report of VRE in the PRN could include one or a multiple number of cases spanning a long period of time. These reports may or may not have been clusters but were reported as such, and the number of reports received and the dates may not accurately portray the data.

Nonetheless, the CNISP VRE PRN provided a rapid and efficient means to provide data on the evolving epidemiology of VRE in Canada. Together with the point-prevalence surveys and the recently established incidence surveillance for VRE, a composite portrait of the emerging epidemiology of VRE in Canada can be established.

Acknowledgments

The Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program acknowledges all of the work performed by the Community and Hospital Infection Control Association, L'Association des professionnels pour la prevention des infections, Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee and the provincial laboratories in collecting information that was voluntarily provided to the Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, Population and Public Health Branch (formerly the Laboratory Centre for Disease Control), Health Canada.

References

- 1.Murray BE. The life and times of the enterococcus.Clin Microbiol Rev 1990;3:46-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Addressing emerging infectious disease threats: A prevention strategy for the United States. Executive Summary.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1994;43:1-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Nosocomial enterococci resistant to vancomycin - United States, 1989-1993.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1993;42:597-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaberg DR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Major trends in the microbial etiology of nosocomial infections.JAMA 1991;91:72S-5S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martone WJ. Spread of vancomycin-resistant enterococci: why did it happen in the United States?Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1998;19:539-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System. Semiannual Report: Aggregated Data from the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December 1999. <www.cdc.gov/ncidod/hip/surveill/NNIS.htm> (Version current at November 2001)

- 7.Noble WC, Virani Z Cree RG. Co-transfer of vancomycin and other resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis NCTC 12201 to Staphylococcus aureus.FEMS Microbiol Lett 1992;72:195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiramatsu K, Hanaki H, Ino T, Yabuta K, Oguri T, Tenover FC. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility.J Antimicrob Chemother 1997;40:135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin - United States.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1997;46:765-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kibsey PC, Willey B, Low DE, et al. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium: first Canadian isolate. 61st Conjoint Meeting of Infectious Diseases.Canadian Association for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Vancouver, November 8 to 10,1993. (Abst) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lior L, Litt M, Hockin J, et al. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci on a renal ward in an Ontario hospital.Can Commun Dis Rep 1996;22:125-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson S, McKenzie M, Unger A, Osei W. VRE in Saskatchewan - the provincial picture.Can J Infect Control 1997;12:31 (Abst) [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Halewyn MA, Vigeant P, Leblanc G, et al. First outbreak of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus colonization in a Quebec hospital.Can J Infect Control 1997;12:31 (Abst) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kagan E, Portnoy D, Allan R, Desjardins D. Hospital-acquired vancomycin-resistant enterococcus: implications for the community.Can J Infect Control 1997;12:31 (Abst) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ofner-Agostini ME, Conly J, Paton S, et al. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in Canada: Results of the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP) 1996 VRE point prevalence surveillance project.Can J Infect Dis 1997;8:73-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conly J, Ofner-Agostini ME, Paton S, et al. The emerging epidemiology of vancomycin resistant enterococci in Canada: Results of the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program Passive Reporting Network. 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.Toronto, September 28 to October 1, 1997. (Abst E- I 29B) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conly J, Shafran S. Emerging epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in Canada.Can J Infect Dis 1997;8:182-5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong-Evans M, Litt M, McArthur MA, et al. Control of transmission of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium in a long-term care facility.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999;20:312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenway CA, Miller MA. Lack of transmission of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in three long-tenn care facilities.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999;20:341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlowsky JA, Zhanel GG, Hoban DJ. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) colonization of high-risk patients in tertiary care Canadian hospitals. Canadian VRE Surveillance Group.Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 1999;35:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huycke MM, Sahm D, Gilmore M. Multiple-drug resistant enterococci: the nature of the problem and an agenda for the future.Emerg Infect Dis 1998;4:239-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyce JM. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. Detection, epidemiology, and control measures.Infect Dis Clin North Am 1997;11:367-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston BL, Conly JM. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci in Canada revisited.Can J Infect Dis 2000;11:127-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tokars JI, Gehr T, Parrish J, Qaiyumi S, Light P. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci colonization at selected outpatient hemodialysis centres. 4th Decennial International Conference on Nosocomial and Healthcare-associated Infections.Atlanta, March 5 to 9, 2000. (Abst P-T2-56) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinberg JP, Howard R, Ho T, Maher M, Hackman B, Jemigan J. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcus in dialysis patients: evidence of hospital acquisition. 4th Decennial International Conference on Nosocomial and Healthcare-associated Infections.Atlanta, March 5 to 9,2000. (Abst P-T2-57) [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Santis LJ, Sturm LK, Thirumoorthi MC, Baran J, Dietrich S. Investigation and control of vancomycin resistant enterococcus in a level III neonatal intensive care unit. 4th Decennial International Conference on Nosocomial and Healthcare-associated Infections.Atlanta, March 5 to 9,2000. (Abst P-T2-58) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai KK, Fontecchio SA, Kelley AL, Melvin ZS. The changing epidemiology of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. 4th Decennial International Conference on Nosocomial and Healthcare-associated Infections.Atlanta, March 5 to 9,2000. (Abst P-T2-62). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goossens H. Spread of vancomycin-resistant enterococci: differences between the United States and Europe.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1998;19:546-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinert RR, Conrads G, Schlaeger JJ, et al. Survey of antibiotic resistance among enterococci in North-Rhine - Westphalia, Germany.J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:1638-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jordens JZ, Bates J, Griffiths DT. Faecal carriage and nosocomial spread of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium.J Antimicrob Chemother 1994;34:515-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ieven M, Vercautem E, Descheemaeker P, Van Laer F, Goossens H. Comparison of direct plating and broth enrichment culture for detection of intestinal colonization by glycopeptide-resistant enterococci among hospitalized patients.J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:1436-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wendt C, Krause C, Xander LV, Loffler D, Floss H. Prevalence of colonization with vancomycin-resistant enterococci in various population groups in Berlin, Germany.J Hosp Infect 1999;42:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coque TM, Tomayko JF, Ricke SC, Okhyusen PC, Murray BE. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci from nosocomial community and animal sources in the United States.Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1996;40:2605-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverrnan J, Thal LA, Perri MB, Bostic G, Zervos MJ. Epidemiologic evaluation of antimicrobial resistance in community-acquired enterococci.J Clin Microbiol 1998;36:830-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wegener HC, Aarestrup FM, Hensen LB, Hammerum AM, Bager F. Use of antimicrobial growth promoters in food animals and Enterococcus faecium resistance to therapeutic antimicrobial drugs in Europe.Emerg Infect Dis 1999;5:329-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnston L, Squires S, Conly J, Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee, et al. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci in Canadian health care facilities: the first year of prospective surveillance.Can J Infect Control 2000;15:2-3.(Abstracts) [Google Scholar]