Abstract

Three paediatric cases of blastomycosis, apparently acquired in or near Toronto, Ontario, a region not known to be endemic for this disease, are described. Blastomycosis was not suspected clinically in any of the three cases, and the diagnosis was established only when the diagnostic net was broadened to include fungal and mycobacterial cultures. All three patients were diagnosed after significant delays, which is consistent with the rarity of the disease in children and its acquisition outside previously accepted geographical boundaries. Pulmonary involvement was present in all three children, while one also had multifocal osteomyelitis. Drug therapy was successful in all three cases, either with amphotericin B followed by itraconazole, or itraconazole alone. Blastomycosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of a patient from the Toronto area who presents with a compatible history despite a negative travel history to known endemic zones.

Key Words: Blastomyces dermatitidis, Itraconazole, Musculoskeletal blastomycosis, Paediatric blastomycosis

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Patient 1

A previously healthy 17-year-old Iraqi girl was admitted to hospital in late 1997 with a three-month history of a swollen, painful left ankle associated with a 4.5 kg weight loss. She had no history of fever, trauma or sexual activity. She had immigrated to Canada six years earlier and had not travelled outside of Toronto, Ontario since her arrival. One month before admission, because of progressive pain, erythema and an inability to bear weight, she was referred to an orthopedic surgeon, who found that she had arthritis of the left ankle joint, pain over the mid-foot, and a tender papule over the talus. A bone scan revealed significant uptake in the left lower tibia and tarsal area, which was compatible with the diagnosis of arthritis. The papule was incised, leaving a sharply demarcated 2 cm ulceration at the incision site. Gram stain and bacterial culture of the purulent fluid were negative. Despite intravenous antibiotics, her symptoms did not improve, and one week later she developed right-sided chest pain. A chest x-ray revealed a small right pleural effusion and infiltrate at the right base.

At The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, an x-ray of the left ankle showed a 1 cm lytic lesion in the talus with no periosteal reaction, as well as a joint effusion in the left ankle (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging revealed extensive osteomyelitis of the talus, navicular and tibia. A sinus tract extended into the skin from the lesion in the talus (Figure 2). Synovial fluid and biopsies of the bone and synovium were negative by Gram, acid fast and calcofluor stains, but on culture they yielded a white, fluffy filamentous fungus identified as Blastomyces dermatitidis. The patient recalled having had a painful, firm swelling at the left temple with associated hair loss a few months before admission. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed a lytic lesion in the lateral aspect of the left orbital roof without intracranial extension (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Radiograph of the left foot and ankle showing a sclerotic lesion in the anterior talus (arrow)

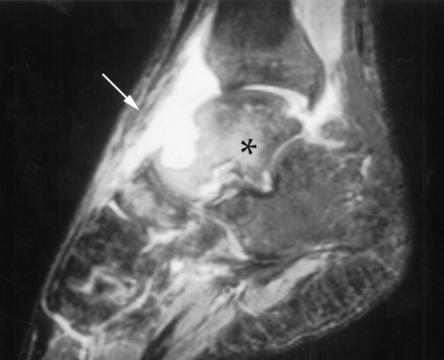

Figure 2.

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the left ankle showing high signal intensity compatible with septic arthritis and osteomyelitis of the talus (asterisk), with a sinus tract draining to the skin (arrow)

Figure 3.

Coronal computed tomography scan showing a lytic lesion in the lateral aspect of the left supraorbital region (arrow)

The patient was treated with alternate day conventional intravenous amphotericin B (1 mg/kg/day) for six days, and was then switched to alternate day amphotericin B lipid complex (5 mg/kg/day) because of renal toxicity and hypokalemia. She completed one month of amphotericin B therapy, and was then switched to oral itraconazole (200 mg/day, 4.7 mg/kg/day) for 10 months. Two months after beginning therapy, a chest x-ray showed resolution of the infiltrate in the right lower lung, and an x-ray of the skull showed a reduction in the size of the lytic lesion. Three months after the start of therapy, a CT scan of the foot showed improvement, with sclerosis and re-establishment of cortical integrity, although a lytic lesion persisted. Three years after completing treatment, she remained well, with a normal ankle x-ray.

Patient 2

An 11-year-old healthy Ethiopian boy presented in 1997 with right maxillary swelling and severe dental caries. He had been in Toronto, Ontario exclusively since his arrival in Canada five years earlier. There was no history of weight loss, night sweats or cough. Two molars and the surrounding necrotic soft tissue were removed surgically, at which time extensive vascular granulation tissue and osteomyelitis of the maxilla were noted. The gingival tissue contained multiple granulomata, with acid fast bacilli, sulfur granules and filaments, which is consistent with both mycobacterial and actinomycotic infections. The Gomori methenamine silver stain was negative for fungi. The tissue was not sent for culture. An HIV test was negative. A tuberculin skin test was newly positive, with 10 mm of induration. A chest x-ray was normal. The patient was diagnosed with mixed actinomycotic and tuberculous osteomyelitis of the maxilla with necrotizing gingivitis. Antimicrobial therapy with amoxicillin, isoniazid, rifampin and ethambutol was initiated.

Over the next two months, the facial swelling resolved, but the granulation tissue in the wound persisted. The patient was only partially compliant with the prescribed medications. Shortly before the completion of his twelve-month antituberculous therapeutic regimen, he experienced new weight loss, fever, anorexia and cough. A chest x-ray showed a new right upper lobe infiltrate and right hilar adenopathy. A CT scan of the maxilla showed improvement of the osteomyelitis and soft tissue changes. To exclude an infection with drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. The calcofluor stain was negative and the culture grew B dermatitidis. Culture and/or stains for mycobacteria, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella species, Actinomyces species and Pneumocystis carinii were negative. Oral itraconazole (100 mg/day, 4 mg/kg/day) was instituted. Within one month, the patient was asymptomatic. After six months of therapy, the oral lesion healed and the pulmonary infiltrate and lymphadenopathy resolved. He remained clinically well four years after completion of therapy.

Patient 3

An 11-year-old previously healthy Canadian girl from Oakville, Ontario presented in 1999 with a one-month history of fever, cough and left-sided chest pain. A chest x-ray revealed blunting of the left costophrenic angle and an infiltrate in the left lower lobe. Despite three courses of antibiotics, her symptoms did not improve. A BAL was performed, and the culture grew B dermatitidis. The patient had no history of travel to a Blastomyces-endemic area. Investigations, including bone scan, revealed no evidence of disseminated disease. She was started on intravenous amphotericin B (1 mg/kg/day). She improved clinically after two weeks and was switched to oral itraconazole (400 mg/day, 7 mg/kg/day) and completed six months of therapy. At the end of therapy, she was entirely well. Her chest x-ray showed mild fibrotic changes that had improved markedly when last seen in March, 2001 - one-and-a-half years after completion of therapy.

The B dermatitidis isolates from patients 1 and 2 were recovered from both brain-heart infusion agar with 5% sheep blood, gentamicin sulfate 5 mg/L and chloramphenicol 16 mg/L (Becton Dickinson, USA) and inhibitory mould agar with ciprofloxacin 5 mg/L (Becton Dickinson, USA), after four to six days of incubation at 30°C. Isolates were identified by the micromorphological characteristics of the yeast in tissue and of the mould state in culture, as well as conversion in vitro on blasto D medium (1).

DISCUSSION

Clinical manifestations

Blastomycosis is rare in all children, except during outbreaks, and is even less common in urban children (2). Additionally, it may be difficult to diagnose because it can mimic other processes such as bacterial or mycobacterial infection or malignancy (2). Primary pulmonary infection, although usually symptomatic, may go unrecognized and may lead to chronic pneumonia and, in many cases, extrapulmonary infection. This was the case with patient 1.

In patients 2 and 3, culture of the BAL fluid confirmed the diagnosis. This was reported to be an effective method of diagnosing pulmonary blastomycosis in children (3,4). In contrast, Schutze et al (5) noted four patients with pulmonary blastomycosis in whom the BAL was negative, which necessitated an open-lung biopsy to make a definitive diagnosis.

Joint disease in blastomycosis (6,7) develops secondary to direct extension from juxta-articular osteomyelitis, or by direct hematogenous seeding (7). As was observed in patient 1, musculoskeletal involvement may precede or occur in the absence of pulmonary symptoms and is usually monoarticular, most commonly affecting the knee, ankle, elbow or wrist. Although direct stains of the purulent synovial fluid may be positive, fungal culture of the fluid or synovial tissue is usually required to diagnose blastomycotic arthritis, as in the case of patient 1 (7).

Therapy

Although pulmonary blastomycosis may occasionally resolve spontaneously without antifungal therapy, treatment is indicated for all diagnosed infections because of its chronicity and tendency to metastasize to distant sites. Amphotericin B has been the gold standard against which treatments have been compared, with a relapse rate of less than 5% in most populations. It is the drug of first choice for life-threatening or central nervous system infections, although its success is tempered by its toxicity and the requirement for intravenous administration. Studies in adults suggest that itraconazole is the oral azole of choice for less serious infections, due to its excellent efficacy and tolerability profile (8), although there have been no randomized trials comparing it directly to amphotericin B. The experience with azoles in children is limited, but a recent review of 10 cases of blastomycosis in children suggested that oral azoles are less successful in children than in adults (9). The validity of this conclusion is called into question by the small number of patients that were described, the lack of comparative prospective data, the doses that were used in some cases, the compliance in other cases, the use of ketoconazole instead of itraconazole, and that the majority of cases were complicated, extrapulmonary and chronic. This report (9) recommended that osteomyelitis in children be treated with a full course of amphotericin B.

Recent evidence-based treatment guidelines for blastomycosis in adults have recommended either primary therapy with itraconazole alone for at least six months, or short-course amphotericin B therapy until clinical stabilization, followed by at least six months of itraconazole, for nonlife-threatening, non-CNS infections (including osteomyelitis) (9). The above strategies were used successfully in patients 2 and 3, and in patient 1, respectively. It should be noted that the short course amphotericin B/itraconazole regimen was successful in the paediatric case of osteomyelitis (patient 1). All treatment regimens require close clinical and radiological monitoring for disease progression or relapse, especially if an azole-containing regimen is used for osteomyelitis (5). Careful follow-up for the first year following cessation of therapy is important to detect relapses.

Epidemiology

Blastomycosis is more common in men who have significant recreational or occupational exposure to outdoor areas (2). Women and children, however, often lack this exposure history and are generally diagnosed very late in the course of the disease. Blastomycosis was delisted as a reportable disease in Ontario in the 1970s, and does not commonly have this status elsewhere in North America. Its prevalence is, therefore, roughly estimated at only 0.5 to 8.3 cases/100,000 persons (5). In some hyperendemic areas (eg, Vilas County, Wisconsin), the prevalence may exceed 40 cases/100,000 persons (10). Most cases of blastomycosis are sporadic, but there have been nine well-described outbreaks reported in the literature (2).

Until 1964, blastomycosis was thought to be geographically restricted to North America. Since then, cases (autochthonous) that were verified to have originated in Africa (11,12), Central America, South America, the Middle East and Asia have been reported. Major endemic areas in North America are scattered mainly in the eastern half of the continent. They include regions around the Mississippi, Ohio and lower Saint Lawrence rivers (1,13,14) as well as Lake Michigan, the mountainous areas of Kentucky, the Carolinas, Virginia, West Virginia, and a continuous band extending from Wisconsin around the north shore of Lake Superior and across much of the boreal Canadian Shield area of northern Ontario and contiguous eastern Manitoba (1,10,15,16). Blastomycosis is seldom acquired west of the 100th meridian of longitude in North America, although there have been a small number of autochthonous cases reported from Saskatchewan, Alberta and New Mexico, mostly in dogs (17).

Most published maps showing the distribution of blastomycosis in North America - eg, Rippon's map (18), which was reprinted by Al-Doory and DiSalvo (17) and modified by Kwon-Chung and Bennett (19) - incorrectly omit the northern Ontario portion of the endemic region. It is included in a world distribution map by Al-Doory and DiSalvo (17). The same map, however, also shows blastomycosis in many regions from which it has not been documented - eg, the extensive tundra regions of the Canadian Northwest Territories. Such maps also invariably record a zone of endemicity for much of southern Ontario contiguous to the north shores of Lakes Erie and Ontario; in fact, no such endemicity has been documented. In the past, however, most cases derived from the northern Ontario endemic zone were diagnosed or treated at southern Ontario institutions, and it is likely that some of these were misinterpreted as having originated in that area. The cases in the present report support the recently described occurrence of autochthonous blastomycosis in the intensely populated, industrial area of southern Ontario, which is concentrated on the north shore of Lake Ontario (20). The closest case that was previously well documented as autochthonous was that of a patient who lived near Sarnia, nearly 300 km west of Toronto, in an area interconnecting with the known northern Ontario endemic zone east of Lake Huron (15).

CONCLUSIONS

The three paediatric patients described in the present report were infected with B dermatitidis, yet they lacked a travel history to previously verified endemic areas, which suggested that the disease was acquired in Toronto. This is important because the diagnosis is already a diagnostic challenge due to its nonspecific clinical presentation, the requirement for special fungal cultures and the rarity of the disease in children. Including Toronto in the list of endemic regions may facilitate making this unusual diagnosis in children and adults. In addition, the cases in the present report support the use of itraconazole in the treatment of paediatric blastomycosis involving the lungs and bones.

References

- 1.St-Germain G, Summerbell RC. Identifying Filamentous Fungi. A Clinical Laboratory Handbook. Belmont: Star Publishers, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradsher RW. Blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis 1992;14(Suppl 1):S82-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rock MJ. The diagnostic utility of bronchoalveolar lavage in immunocompetent children with unexplained infiltrates on chest radiograph. Pediatrics 1995;95:373-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkrinawi S, Reed M. Clinical and radiologic features of pulmonary blastomycosis in children. Am Respir Crit Care J 1995;151:A94. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schutze GE, Hickerson SL, Fortin EM, et al. Blastomycosis in children. Clin Infect Dis 1996;22:496-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald PB, Black GB, MacKenzie R. Orthopaedic manifestations of blastomycosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990;72:860-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George AL Jr, Hays JT, Graham BS. Blastomycosis presenting as monoarticular arthritis: The role of synovial fluid cytology. Arthritis Rheum 1985;28:516-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dismukes WE, Bradsher RW Jr, Cloud GC, Pappas PG, Kauffman CA. Itraconazole therapy for blastomycosis and histoplasmosis. Am J Med 1992;93:489-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman SW, Bradsher RW Jr, Campbell GD Jr, Pappas P, Kauffman CA. Practice guidelines for the management of patients with blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:679-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumgardner DJ, Buggy BP, Mattson BJ, Burdick JS, Ludwig D. Epidemiology of blastomycosis in a region of high endemicity in north central Wisconsin. Clin Infect Dis 1992;15:629-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen LM, Golitz LE, Wilson ML. Widespread papules and nodules in a Ugandan man with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: African blastomycosis. Arch Dermat 1996;132:821-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frean JA, Carman WF, Crewe-Brown HH, Culligan GA, Young CN. Blastomyces dermatitidis infections in RSA. South African Med J 1989;76:13-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med 1986;314:529-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.St-Germain G, Murray G, Duperval R. Blastomycosis in Quebec (1981-90): Report of 23 cases and review of published cases from Quebec. Can J Infect Dis 1993;4:89-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakerspigel A, Kane J, Schaus D. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis from an earthen floor in southwestern Ontario, Canada. J Clin Microbiol 1986;24:890-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kane J, Righter J, Krajden S, Lester RS. Blastomycosis: A new endemic focus in Canada. CMAJ 1983;129:728-31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Doory Y, DiSalvo AF. Blastomycosis. New York: Plenum Medical Books, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rippon JW. Medical Mycology. The Pathogenic Fungi and the Pathogenic Actinomycetes, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennett JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lester RS, DeKoven JG, Kane J, Simor AE, Krajden S, Summerbell RC. Novel cases of blastomycosis acquired in Toronto, Ontario. CMAJ 2000;163:1309-12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]