Abstract

The application of cytogenetic and molecular genetic analyses to paediatric sarcomas has identified a number of characteristic changes associated with types and subtypes of sarcomas. This has led to increased understanding of the underlying molecular biology of some sarcomas and provided an important adjunct to standard morphological and immunohistochemical diagnoses. Characteristic genetic abnormalities, particularly specific chromosome translocations and associated fusion genes, have diagnostic and in some cases prognostic value. There is also the potential to detect micrometastastic disease. Fusion genes are most readily detected by fluorescence in situ hybridisation and reverse transcription‐PCR technologies. The expression profiles of tumours with specific fusion genes are characteristically similar and the molecular signatures of sarcomas are also proving to be of diagnostic and prognostic value. Furthermore, fusion genes and other emerging molecular events associated with sarcomas represent potential targets for novel therapeutic approaches which are desperately required to improve the outcome of children with certain categories of sarcoma, including rhabdomyosarcomas and the Ewing's family of tumours. Increased understanding of the molecular biology of sarcomas is leading towards more effective treatments which may complement or be less toxic than conventional radiotherapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy. Here we review paediatric sarcomas that have associated molecular genetic changes which can increase diagnostic and prognostic accuracy and impact on clinical management.

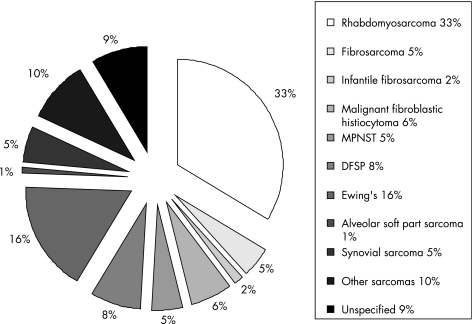

Sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of tumours that are generally classified according to the type of tissue that they resemble, such as rhabdomyosarcoma which resembles developing skeletal muscle. However, the cell type(s) that gives rise to particular sarcomas is not clear. Sarcomas represent a higher proportion of cancers in children compared to adults, with 11% of all childhood cancers being sarcomas compared with 1% in the adult population. Therefore, although relatively rare, they comprise a significant proportion of paediatric oncology practice, with an incidence of 11.0 per million in children under the age of 20 (fig 1).1 In high‐risk categories of sarcoma the overall outcome has not significantly improved in several decades, despite many clinical trials in different continents.2

Figure 1 Distribution of childhood sarcomas.1 MPNST, malignant peripheral nerve sheet tumour; DFSP, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

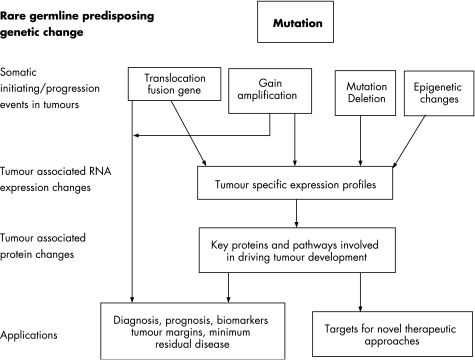

Sarcomas can pose particular challenges in terms of their differential diagnosis, and accurate diagnosis is important in optimising the clinical management of patients. A number of types and subtypes of sarcomas possess characteristic genetic abnormalities, including specific chromosome translocation and associated fusion genes, which have diagnostic or in some cases prognostic value. These genetic abnormalities and other emerging molecular events associated with sarcomas represent potential targets for novel therapeutic approaches which are desperately required to improve outcome in certain categories of sarcomas. Novel treatments that are less toxic than conventional radiotherapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy could reduce long‐term damage and the risk of secondary malignancies as well as improve the rate of survival. Here we review paediatric sarcomas that have associated molecular genetic changes which can be used to aid diagnosis and the clinical management of patients (table 1). We also discuss the potential for future therapeutic options for children with specific sarcomas based on our increasing understanding of the aberrant signalling pathways driving sarcoma development and the identification of key molecular targets in tumour cells (fig 2).

Table 1 Chromosomal rearrangements in childhood sarcoma.

| Tumour type | Chromosomal rearrangement | Genes involved | Prevalence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma | t(2;13)(q35:q14) | PAX3‐FOXO1a | ∼70% | 3 |

| t(1;13)(p36;q14) | PAX7‐FOXO1a | ∼10% | 4 | |

| Alveolar soft part sarcoma | t(X;17)(p11;q25) | ASPL‐TFE3 | ∼100% | 5 |

| Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma | t(12;16)(q13,p11) | FUS‐ATF1 | NA | 6 |

| Clear cell sarcoma/malignant melanoma of the soft parts | t(12;22)(q13;q12) | EWS‐AFT1 | NA | 7 |

| Congenital fibrosarcoma/mesoblastic nephroma | t(12;15)(p13,q25) | ETV‐NTRK3 | ∼100% | 8 |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans | Ring chromosome with sequences from chromosome 17 and 22 t(17;22)(q22;q13) | COL1A1‐PDGFB | 92% | 9 |

| Desmoplastic small round cell tumour | t(11;22)(p13;q12) | EWS‐WT1 | 93% | 10 |

| Ewing's sarcoma family of tumours | t(11;22)(q24:q12) | EWS‐FLI1 | 85% | 11 |

| t(21;22)(q22:q12) | EWS‐ERG | 10% | 11 | |

| t(7;22)(p22;q12) | EWS‐ETV1 | ∼1% | ||

| t(7;22)(q21;q12) | EWS‐E1AF | ∼1% | ||

| t(2;22)(q33;q12) | FUS‐ERG | ∼1% | ||

| EWS‐FEV | ∼1% | |||

| Giant cell fibroblastoma (juvenile form of DFSP) | t(17;22)(q22,q13) | COL1A1‐PDGFB | 100% | 9 |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour | t(2;19)(p23;q13) | TPM4‐ALK | NA | 12 |

| t(1:2)(q22:p23) | TPM3‐ALK | 12 | ||

| t(2;17)(p23:q23) | CLTC‐ALK | 13 | ||

| t(2;2)(p23:q13) | RANBP2‐ALK | 14 | ||

| Rhabdoid tumour | t(1;22)(p36:q11.2) | SNFS/INI1 | NA | 15 |

| Synovial sarcoma | t(X:18)(p11.2;q11.2) | SSX1/SYT | 63% | 16 |

| SSX2/SYT | 37% | 16 | ||

| SSX4/SYT | rare | 17 |

NA, not available.

Figure 2 Application of molecular genetics to tumour development, diagnosis and treatment.

Predisposition to sarcomas

Germ‐line genetic abnormalities are known to predispose to the development of sarcomas, in many cases through increasing susceptibility to DNA damage (table 2). Germ‐line mutations of the p53 tumour suppressor gene are associated with Li–Fraumeni syndrome and an increased risk of tumours including sarcomas. Ten per cent of children with rhabdomyosarcoma have been identified with p53 mutations.18,19 Germ‐line mutation and subsequent inactivation of a second copy of the RB1 gene result in retinoblastoma through the classic two‐hit mechanism. This genetic change is also associated with an increased frequency of osteosarcomas and rhabdomyosarcomas. Additionally, predisposition to osteosarcoma is also found in Rothmund–Thomson and Werner syndromes that are associated with mutations in the RECQL4 and RECQL2 genes, respectively, which are involved in genomic instability.20 Costello syndrome is caused by mutation of the HRAS gene at 11p15.5, a locus of frequent allelic imbalances in sporadic embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas. Children with Costello syndrome have a high incidence of rhabdomyosarcoma,21 but significantly sporadic embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas show uniparental disomy at the same locus, which is not driven by HRAS mutation.22 Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome also involves the 11p15.5 locus although the gene involved is not yet clear. This syndrome is associated with overgrowth, malformations and predisposition to embryonic tumours including rhabdomyosarcomas23

Table 2 Syndromes which predispose to paediatric sarcoma.

| Cancer syndrome | Locus | Gene | Characteristic malignancy | Sarcoma type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome | 11p15.5 | Unknown | Wilms' tumour, hepatoblastoma, adrenocortical carcinoma | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 23 |

| Bloom syndrome | 15q26.1 | RECQL3/BLM | All common malignancies with increased frequency | 24 | |

| Costello syndrome | 11p15.5 | HRAS | Rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, transitional cell carcinoma | 21 | |

| Li–Fraumeni syndrome | 17p13.1 | TP53 | Breast carcinoma, CNS tumours | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 25, 26 |

| Osteosarcoma | |||||

| Hereditary retinoblastoma | 13q14 | RB1 | Retinoblastoma | Osteosarcoma | 27 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | |||||

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | 17q11.1 | NF1 | Glioma, neurofibroma | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 28 |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheet tumour | |||||

| Noonan syndrome | 12q14.13 | PTPN11 | Juvenile myelomonocytic leukaemia, neuroblastoma | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 29 |

| Gorlin syndrome | 9q22 | PTCH | Basal cell carcinoma, medulloblastoma | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 30 |

| Rapadilino and Rothmud–Thomson syndrome | 8q24.3 | RECQL4 | Osteosarcoma | 20 | |

| Werner syndrome | 8p11.2 | RECQL2/WERN | Osteosarcoma | 20 | |

| Mosaic variegated aneuploidy | 15q15 | BUB1B | Wilms' tumour, leukaemia | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 31, 32 |

Approaches to the diagnosis and prognosis of paediatric sarcomas

Accurate diagnosis of paediatric sarcomas involves rational integration of clinical parameters, morphological features and investigation of tumour samples by appropriate immunohistochemistry and genetic analyses (table 1). Standard cytogenetic analysis can be used to identify chromosome translocations but it requires fresh material. Preparation and analysis of chromosomes can be both technically difficult and time consuming. The advantage of karyotype analysis is that it gives a global view of chromosome aberrations and can be combined with chromosome painting or fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) approaches to aid definition of changes. The most convenient and widely used approaches for inferring the presence of specific fusion genes are reverse transcription PCR (RT‐PCR) and interphase FISH. Using these methods fusion genes can be detected in fresh, snap frozen and formalin fixed paraffin embedded tumour material, including fine needle biopsy samples. RT‐PCR and FISH detect specific fusion gene transcripts and disruption or juxtaposing of specific DNA segments associated with a translocation, respectively. The list of variant translocations has grown over the years and therefore a negative result for a particular gene fusion may not exclude a particular diagnosis. Also, although the specificity of particular gene fusions is high it is not exclusive. For example, the TMP3‐ALK and CTLC‐ALK gene fusions can be associated with both myofibroblastic tumours and anaplastic large cell lymphomas.12,13,33,34 Translocations involving the EWS gene are associated with several tumour types and therefore identification of disruption of the EWS gene using FISH analysis is not specific, although useful when variation in fusion partners occurs (table 1). The exons which fuse in, for example, the EWS‐FLI1 fusion genes associated with Ewing's sarcomas vary and therefore RT‐PCRs need to be designed in order to detect these. The sensitivity of RT‐PCR allows the detection of micrometastases; this has been demonstrated in a number of sarcomas although the clinical significance of this is not yet clear. Quantification of RT‐PCR products through real time RT‐PCR analyses may ultimately become useful in clinical management.35

Different fusion gene products are associated with the same sarcoma type, involving either different genes or different exons of the same genes (table 1). This may affect the molecular biology of the tumour cells and the clinical behaviour of the tumour. These different fusion proteins and other aberrantly expressed proteins associated with tumours may have profound effects on the overall RNA expression profile associated with a tumour. Both the fusion gene types and the expression profiles of tumours are emerging as having prognostic significance in sarcomas and are included in the discussion below on individual sarcoma types.

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcomas (RMS) are the most common soft tissue sarcomas in children and are thought to be derived from a primitive mesenchymal cell committed to the skeletal lineage but arrested in the processes of differentiation.36 The main histological subtypes are alveolar (ARMS) (20%) and embryonal (ERMS) (60%); survival rates vary from <25% to >95% respectively for these subtypes.37 Molecular genetics has increased diagnostic accuracy of these tumours and is anticipated to increasingly impact on the management of patients.

Seventy per cent of ARMS harbour the translocation t(2;13)(q35:q14) which fuses the 5′ end of PAX3 with the 3′ end of the FOXO1a gene.3 A further 10% of ARMS are associated with fusion of PAX7 to the FOXO1a gene.3 The remaining 20% of ARMS do not have these fusion genes detectable by routine RT‐PCR and comprise cases with a very low expression of a fusion gene, a rare variant fusion, or are true fusion negative cases.4 In addition to being of diagnostic relevance, the fusion status correlates with clinical outcome in RMS.

Evaluating clinical features in 34 patients with RMS, Kelly et al found significantly longer overall and event free survival in patients with tumours harbouring PAX7‐FOXO1a fusion gene in comparison with the PAX3‐FOXO1a group of patients.38 In univariate analysis of 80 patients with localised disease, comparing patients with PAX3‐FOXO1a and PAX7‐FOXO1a, the presence of the PAX3‐FOXO1a fusion gene was an adverse prognostic factor, implying that these patients might benefit from treatment intensification.39 Sorensen et al evaluated 78 ARMS tumours, reporting an overall survival rate of 8% for patients with metastatic disease and PAX3‐FOXO1a, whereas survival was 75% for patients with PAX7‐FOXO1a tumours.40 Therefore the presence of a PAX3‐FOXO1a fusion gene is an indicator of adverse outcome in RMS, but independence of alveolar histology has not been tested in any clinical trials.

The fusion genes encode chimeric transcription factors with the DNA binding domain from PAX3/PAX7 fused to the potent transactivation domain of FOXO1a. Wild type PAX3 and PAX7 are transcription factors required for primary myoblast migration and specification of muscle satellite cells, respectively.41 The fusion proteins are 10 to 100‐fold more potent as transcription factors than the wild type PAX3 or PAX7 gene products.42 Although the fusion protein can transform NIH3T3 cells in vitro,43 this rarely results in tumours in vivo,44 without additional changes such as disruption to the INK4a/ARF and TP53 pathways.45

Wild type FOXO1a regulates myoblast differentiation and cell fusion. Loss of a complete copy of the FOXO1a gene as a result of the translocation event in RMS results in reduced FOXO1a expression.41 Artificial restoration of FOXO1a expression has been shown to induce G2/M cell cycle arrest, morphological changes resembling muscle cell differentiation and apoptosis through increased transcription of caspase 3.41 Restoration of FOXO1a function may represent a potential pathway for therapeutic intervention. Trp53/Fos double knockout mice develop highly proliferative and invasive ERMS of face and neck with 90% penetrance providing an excellent model for RMS development in humans.46

A number of downstream targets of the fusion gene have been shown through expression analyses, such as EN2, BVES, FLT1 Itam2A and MET.47,48MET encodes the HGF/SF receptor (hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor); silencing MET expression in both ERMS and ARMS cell lines impaired cell replication, survival, invasiveness and anchorage independent growth.49 Furthermore, RMS were induced in mice at a high frequency and with short latency through simultaneous loss of INK4a/ARF function and disruption of MET.50 MET represents a possible therapeutic target in RMS and in gastric tumours, which overexpress MET through amplification events, a MET inhibitor has recently been shown to be effective.51

Recurrent translocations have not been reported in ERMS. However, ERMS and ARMS in addition to the presence of translocations have characteristic chromosomal imbalances including amplification events. Furthermore, ARMS and the rare anaplastic variant of ERMS both exhibit a high frequency of amplification events involving similar genomic regions, which may contribute to their similar adverse clinical outcome.36,52,53 Amplification of MYCN is used in the stratification of neuroblastoma and has been described in RMS.54,55 Significantly, amplification and overexpression of MYCN in ARMS has been associated with adverse clinical outcome in ARMS, but not ERMS, and MYCN also represents a possible molecular therapeutic target.56 The hallmark of ERMS tumours is recurrent loss of heterozygosity, loss of imprinting or paternal disomy at the 11p15 locus which leads to overexpression of the IGFII gene.57,58 Coupled with a report of amplification of the 15q25–26 region encompassing the IGFR1 locus in an ERMS case,53 this suggest a role for the IGF pathway in ERMS development.

Expression profiling at the chromosomal level has shown discriminating patterns of expression in ARMS and ERMS.59 Higher resolution expression analysis has also demonstrated distinctive expression profiles in fusion gene positive and negative tumours. A subset of genes were able to identify three ARMS risk groups with very different overall survival rates (7%, 48% and 95% overall survival).60 Further discriminatory patterns and key genes are likely to emerge from this and similar data.

Ewing's sarcoma family of tumours

The Ewing's family of tumours (ESFTs) encompasses Ewing's sarcoma, peripheral neuroectodermal tumour, Askin tumour and neuroepithelioma. For Ewing's sarcoma, 5‐year survival with combination treatment of surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy is 55–60% in localised disease, while patients with metastatic disease have a 5‐year survival of only 30%. The ESFTs share genetic alterations consisting of a number of translocations, most frequently (80–85%) the translocation t(11;22)(q24;q12) which results in the fusion of the 5′ end of the EWS gene to the 3′ end of FLI1.61,62 A further 5–10% of these tumours are associated with the t(21;22)(q22;q21) and EWS‐ERG fusion gene.7,63 In addition there are rare variant translocations in which EWS is fused to other members of the ETS family genes (table 1). Depending on genomic breakpoints and the exons fused, there are two types of EWS‐FLI1 transcripts: EWS exon 7 is most frequently fused to either FLI1 exon 6 (type‐1 transcript (60%)) or FLI1 exon 5 (type‐2 transcript (25%)).64,65 Patients with a type‐1 EWS‐FLI1 fusion transcript have been reported to have a better disease‐free survival compared with those with other fusion transcripts types.66 The type‐1 fusion encodes a less active chimeric transcription factor67 and is associated with a lower proliferative index.64 However, other authors report a lack of evidence for the EWS‐FLI1 type 1 fusion impacting on disease‐free or overall survival, but in comparison with EWS‐ERG tumours.68

EWS belongs to a family of genes that encode proteins involved in RNA processing, while FLI1 is part of the ETS family of DNA‐binding transcription factors. EWS‐FLI1 is a more potent transcriptional activator than FLI1.62 Furthermore, EWS‐FLI1 promotes transforming and tumourigenic activities,69,70 which are abrogated when either EWS or FLI1 are mutated. The fusion protein affects the cell cycle, disrupts signal transduction pathways, affects cell differentiation and changes the status of p53 tumour suppressor.3 Mutation of p53 and homozygous deletion of p16/p14ARF have been found in 25% of 60 patients with Ewing's sarcoma. This subgroup is defined by highly aggressive tumours which have poor response to chemotherapy.71

Gene expression profiling reveals an association of the EWS‐FLI1 fusion gene with overexpressed genes encoding cell cycle regulators, genes associated with invasion and metastasis and down‐regulated genes including tumour suppressor genes and inducers of apoptosis.72

Modulation of the tumourigenic properties of EWS‐FLI1 may also take place through the basic fibroblast growth factor pathway.73 EWS‐FLI1 suppresses TGF‐type II receptor transcription and histone deacetylase inhibitors can reverse this effect. Restoring TGF signalling in this way has been shown to suppress the growth of Ewing's cells.74 Another promising agent that down‐regulates EWS‐FLI1 protein and restores TGF‐receptor II expression is rapamycin which acts by inhibiting the intracellular protein kinase mTOR.75 IGF1 is also a downstream target of the EWS‐FLI1 protein.76 IGF1 and IGF1R trigger growth, proliferation and antiapoptotic signals in tumour cells. The insulin‐like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP3) is expressed at low levels in ESFTs and influences regulation of IGF1. Silencing EWS‐FL1 with siRNA is associated with increased levels of IGFBP3 and apoptosis, and exogenous IGFBP3 significantly inhibits the growth of Ewing's cell lines in culture. Recombinant IGFBP3 could therefore have therapeutic potential in ESFTs.77,78

Desmoplastic small round cell tumour

The desmoplastic small round cell tumour (DSRCT) is a rare, poorly understood neoplasm primarily affecting adolescents and young adult males. It presents with widespread intra‐abdominal serosal involvement not related to a particular organ system.79 DSRCT is usually a disseminated tumour at diagnosis and most patients die within 2 years despite aggressive treatment. In children the 3 and 5 year survival is 44% and 15%, respectively.80

DSRCTs harbour a specific translocation t(11;22)(p13;q12) which juxtaposes the 5′ end of the EWS gene to the 3′ WT1 (Wilms' tumour) tumour suppressor gene, resulting in formation of EWS‐WT1 fusion protein.81 As in the ESFT, the EWS‐WT1 fusion gene includes up to exon 7 or more rarely exons 8–10 of the EWS gene.82,83 The fusion includes exons 8–10 of the WT1 gene. EWS fusion products have been shown to be potent transcriptional activators and can transform NIH3T3 cells. The amino‐terminal domain of EWS is required for both of these activities. The EWS‐WT1 chimeric protein probably functions as an inappropriately expressed transactivator, whereas native WT1 is primarily a repressor.

The downstream targets for EWS‐WT1 include exocytosis regulator BAIAP3, TALLA 1 (T‐cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia associated antigen), IL‐2R, MLF1 and LRRC15. LRRC15 probably contributes to the invasive phenotype of DSRCT.84 EWS‐WT1 induces expression of platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) growth factor, which has weak transforming capacity but is a potent mitogen and chemo‐attractant for fibroblasts and endothelial cells. PDGF contributes to the characteristic reactive fibrosis associated with DSRCT.85 A phase I clinical trial using the PDGF inhibitor SU 101 (leflunomide) has been conducted with encouraging results.86

Giant cell fibroblastoma

Giant cell fibroblastoma (GCF) represents the juvenile form of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP),87,88 occurring exclusively in the first two decades.9 Although histologically different these two diseases share a number of similarities: clinical localisation and course, CD34 positivity, and most importantly, genetic background. Genetic changes in both diseases result in the COL1A1‐PDGFB fusion protein. COL1A1 is located at 17q22 encoding α1 chain of type 1 collagen, while the PDGFB gene located at 22q13 encodes the β chain of the PDGF ligand. The mechanism of genetic alteration is different and appears to be age related: in GCF this is mostly an unbalanced translocation t(17;22), while in DFSP it appears as supernumerary ring chromosome. In both disorders the fusion transcript is under the control of the regulatory sequences of the COL1A1 gene, which leads to continuous activation of PDGFR receptor tyrosine kinase that promotes tumour growth. Imatinib mesylate is a small molecule inhibitor of tyrosine kinases including PDGFR, and the clinical response in adults has been dramatic.89 However, there has not been a specific clinical trail for imatinib in children with GCF.90 The use of other PDGFR inhibitors, such as sunitinib and sorafenib, has recently commenced in patients with metastatic DFSP.91

Synovial sarcoma

Synovial sarcoma is the second most common soft tissue sarcoma in children and adolescents. It arises in the para‐articular structures of the limbs, though it might occur in other locations. This is a spindle cell tumour which presents as two major histological subtypes, biphasic or monophasic, defined by the presence or absence of areas of glandular epithelial differentiation, respectively. Treatment is multimodal and 5 and 10 year survival rates are 60% and 50% respectively.92

The main molecular event is a reciprocal translocation t(X:18)(p11;q11) present in more than 90% of synovial sarcomas.93 The translocation results in fusion of the SYT gene at 18q11 to either the SSX1 gene (Xp11.23) or the SSX2gene (Xp11.21),94 or in very rare case to the SSX4 gene.95 Seventy‐five per cent of synovial sarcomas involve the SSX1 fusion type which is associated with biphasic histology, while 12% of tumours involve SSX2 fusions in association with monophasic histology. Several studies have shown that the type of fusion has prognostic implications.16,96,97SYT‐SSX1 is associated with higher proliferation rate and has shorter progression‐free survival.96SYT‐SSX status has been demonstrated as the single most significant prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with localised disease at diagnosis in a multi‐institutional study of 243 patients.16 In patients with metastatic disease, the tumour spread seems to outweigh any influence of the fusion protein.98 However, a European study of 141 patients challenged these findings.99

Identification of the fusion gene is a useful tool in difficult diagnostic cases, and may be valid for stratification. Blocking the fusion gene with antisense oligonucleotides results in decreased expression of the DNA repair gene XRCCR4 and cyclin D1.100 The fusion protein may serve as target for tumour specific cytotoxic lymphocytes T,101 which a phase I pilot trial has confirmed.102 Alterations affecting cell cycle regulators involved in the G1 checkpoint are also frequent events in synovial sarcomas and could be associated with poor outcome.103 Bcl‐2 is overexpressed in 79–94% of biphasic SS and likely to be related to protecting cells from apoptosis, which could contribute to their resistance to conventional chemotherapy.104 Overexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is found in 55.3% of tumours by immunohistochemistry105; a phase II trial of the EGFR inhibitors in patients with both localised and metastatic synovial sarcomas that overexpress EGFR has commenced in Europe.106 Quantitative RT‐PCR analysis of ErbB2 has shown that it is expressed in 73.3% of patients with synovial sarcoma.105 cDNA microarray analysis indicates that, in contrast to other soft tissue sarcomas, ErbB2 expression is found in synovial sarcoma.107 A phase II clinical trial of trastuzumab, which targets ErbB2, in recurrent or metastatic synovial sarcoma is underway in adult patients.108

Conclusions

In childhood sarcomas specific fusion genes have provided a sensitive and accurate approach to assist with diagnosis, treatment stratification and in some cases prognostication. However, inconsistencies have emerged from different studies supporting prognostic factors.16,38,39,40,64,65,68,99 Possible reasons for these discrepancies include different study designs and treatment protocols, confounding variables associated with retrospective analyses and use of diverse molecular methods. In order to resolve these issues, prognostic factors should be validated using uniform and multiple methods in both retrospective investigations and prospective multinational multicentre studies.109 The Euro Ewing's 99 Clinical Trial (in accrual at the moment) plans to prospectively study the prognostic significance of EWS‐FLI1 transcripts as well as the value of detecting minimal residual disease.110

The advent of the human genome map and techniques to interrogate abnormalities in multiple genes has seen the identification of genes and pathways associated with the development sarcomas, both with and without fusion genes. Patterns of gene expression provide a new approach to classifying tumours and predicting clinical behaviour. In addition, understanding of the underlying molecular biology in paediatric sarcomas is leading to the identification of targets for novel therapeutic approaches. Targeted agents have already been used in some sarcoma patients, enabling treatment with improved efficacy and reduced toxicity and long‐term side effects, which is of utmost importance in this young group of cancer patients.

Take‐home messages

Molecular genetic analyses of childhood sarcomas have identified characteristic genetic aberrations associated with tumour types.

Chromosome translocations and their resultant gene fusion products are of particular diagnostic and prognostic value.

These can be identified by cytogenetic analysis, interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation and reverse transcription PCR.

Genetic changes can also predispose to sarcoma development, frequently through increasing the probability of changes occurring to DNA.

Increasing understanding of the molecular consequences of the genetic changes that are involved in the development of paediatric sarcomas is leading to identifying further clinically useful markers and targets for novel therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Kathy Pritchard‐Jones for her critical comments in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Gurney J G Y J, Roffers S D, Smith M A.et alSoft tissue sarcomas. SEER Pediatric Monograph. National Cancer Institute 1995

- 2.Carli M, Colombatti R, Oberlin O.et al European intergroup studies (MMT4‐89 and MMT4‐91) on childhood metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol 2004224787–4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xia S J, Barr F G. Chromosome translocations in sarcomas and the emergence of oncogenic transcription factors. Eur J Cancer 2005412513–2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr F G, Qualman S J, Macris M H.et al Genetic heterogeneity in the alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma subset without typical gene fusions. Cancer Res 2002624704–4710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladanyi M, Lui M Y, Antonescu C R.et al The der(17)t(X;17)(p11;q25) of human alveolar soft part sarcoma fuses the TFE3 transcription factor gene to ASPL, a novel gene at 17q25. Oncogene 20012048–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters B L, Panagopoulos I, Allen E F. Genetic characterization of angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma identifies fusion of the FUS and ATF‐1 genes induced by a chromosomal translocation involving bands 12q13 and 16p11. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2000121109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zucman J, Melot T, Desmaze C.et al Combinatorial generation of variable fusion proteins in the Ewing family of tumours. Embo J 1993124481–4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourgeois J M, Knezevich S R, Mathers J A.et al Molecular detection of the ETV6‐NTRK3 gene fusion differentiates congenital fibrosarcoma from other childhood spindle cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 200024937–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sirvent N, Maire G, Pedeutour F. Genetics of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans family of tumors: from ring chromosomes to tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2003371–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerald W L, Ladanyi M, de Alava E.et al Clinical, pathologic, and molecular spectrum of tumors associated with t(11;22)(p13;q12): desmoplastic small round‐cell tumor and its variants. J Clin Oncol 1998163028–3036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burchill S A. Ewing's sarcoma: diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications of molecular abnormalities. J Clin Pathol 20035696–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawrence B, Perez‐Atayde A, Hibbard M K.et al TPM3‐ALK and TPM4‐ALK oncogenes in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Am J Pathol 2000157377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bridge J A, Kanamori M, Ma Z.et al Fusion of the ALK gene to the clathrin heavy chain gene, CLTC, in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Am J Pathol 2001159411–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma Z, Hill D A, Collins M H.et al Fusion of ALK to the Ran‐binding protein 2 (RANBP2) gene in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 20033798–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huret J L, Dessen P, Bernheim A. Atlas of genetics and cytogenetics in oncology and haematology, updated. Nucleic Acids Res 200129303–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladanyi M, Antonescu C R, Leung D H.et al Impact of SYT‐SSX fusion type on the clinical behavior of synovial sarcoma: a multi‐institutional retrospective study of 243 patients. Cancer Res 200262135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skytting B, Nilsson G, Brodin B.et al A novel fusion gene, SYT‐SSX4, in synovial sarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 199991974–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diller L, Sexsmith E, Gottlieb A.et al Germline p53 mutations are frequently detected in young children with rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Invest 1995951606–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moutou C, Le Bihan C, Chompret A.et al Genetic transmission of susceptibility to cancer in families of children with soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer 1996781483–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin J, Kwon Y T, Varshavsky A.et al RECQL4, mutated in the Rothmund‐Thomson and RAPADILINO syndromes, interacts with ubiquitin ligases UBR1 and UBR2 of the N‐end rule pathway. Hum Mol Genet 2004132421–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerr B, Delrue M A, Sigaudy S.et al Genotype‐phenotype correlation in Costello syndrome: HRAS mutation analysis in 43 cases. J Med Genet 200643401–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kratz C P, Steinemann D, Niemeyer C M.et al Uniparental disomy at chromosome 11p15.5 followed by HRAS mutations in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma: lessons from Costello syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 200716374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steenman M, Westerveld A, Mannens M. Genetics of Beckwith‐Wiedemann syndrome‐associated tumors: common genetic pathways. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2000281–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amor‐Gueret M. Bloom syndrome, genomic instability and cancer: the SOS‐like hypothesis. Cancer Lett 20062361–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malkin D. p53 and the Li‐Fraumeni syndrome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 19936683–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srivastava S, Zou Z Q, Pirollo K.et al Germ‐line transmission of a mutated p53 gene in a cancer‐prone family with Li‐Fraumeni syndrome. Nature 1990348747–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wunder J S, Czitrom A A, Kandel R.et al Analysis of alterations in the retinoblastoma gene and tumor grade in bone and soft‐tissue sarcomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 199183194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsui I, Tanimura M, Kobayashi N.et al Neurofibromatosis type 1 and childhood cancer. Cancer 1993722746–2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y, Takita J, Hiwatari M.et al Mutations of the PTPN11 and RAS genes in rhabdomyosarcoma and pediatric hematological malignancies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 200645583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorlin R J. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med 20046530–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanks S, Coleman K, Reid S.et al Constitutional aneuploidy and cancer predisposition caused by biallelic mutations in BUB1B. Nat Genet 2004361159–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanks S, Coleman K, Summersgill B.et al Comparative genomic hybridization and BUB1B mutation analyses in childhood cancers associated with mosaic variegated aneuploidy syndrome. Cancer Lett 2006239234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Touriol C, Greenland C, Lamant L.et al Further demonstration of the diversity of chromosomal changes involving 2p23 in ALK‐positive lymphoma: 2 cases expressing ALK kinase fused to CLTCL (clathrin chain polypeptide‐like). Blood 2000953204–3207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamant L, Dastugue N, Pulford K.et al A new fusion gene TPM3‐ALK in anaplastic large cell lymphoma created by a (1;2)(q25;p23) translocation. Blood 1999933088–3095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDowell H P, Donfrancesco A, Milano G M.et al Detection and clinical significance of disseminated tumour cells at diagnosis in bone marrow of children with localised rhabdomyosarcoma. Eur J Cancer 2005412288–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson J, Gordon A, Pritchard‐Jones K.et al Genes, chromosomes, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 199926275–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breneman J C, Lyden E, Pappo A S.et al Prognostic factors and clinical outcomes in children and adolescents with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma—a report from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV. J Clin Oncol 20032178–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelly K M, Womer R B, Sorensen P H.et al Common and variant gene fusions predict distinct clinical phenotypes in rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol 1997151831–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson J, Gordon T, McManus A.et al Detection of the PAX3‐FKHR fusion gene in paediatric rhabdomyosarcoma: a reproducible predictor of outcome? Br J Cancer 200185831–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sorensen P H, Lynch J C, Qualman S J.et al PAX3‐FKHR and PAX7‐FKHR gene fusions are prognostic indicators in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol 2002202672–2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bois P R, Izeradjene K, Houghton P J.et al FOXO1a acts as a selective tumor suppressor in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. J Cell Biol 2005170903–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Bennicelli J L, Fredericks W J, Wilson R B.et al Wild type PAX3 protein and the PAX3‐FKHR fusion protein of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma contain potent, structurally distinct transcriptional activation domains. Oncogene 199511119–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheidler S, Fredericks W J, Rauscher F J., 3rdet al The hybrid PAX3‐FKHR fusion protein of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma transforms fibroblasts in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996939805–9809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lagutina I, Conway S J, Sublett J.et al Pax3‐FKHR knock‐in mice show developmental aberrations but do not develop tumors. Mol Cell Biol 2002227204–7216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keller C, Arenkiel B R, Coffin C M.et al Alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas in conditional Pax3:Fkhr mice: cooperativity of Ink4a/ARF and Trp53 loss of function. Genes Dev 2004182614–2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fleischmann A, Jochum W, Eferl R.et al Rhabdomyosarcoma development in mice lacking Trp53 and Fos: tumor suppression by the Fos protooncogene. Cancer Cell 20034477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barber T D, Barber M C, Tomescu O.et al Identification of target genes regulated by PAX3 and PAX3‐FKHR in embryogenesis and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Genomics 200279278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ginsberg J P, Davis R J, Bennicelli J L.et al Up‐regulation of MET but not neural cell adhesion molecule expression by the PAX3‐FKHR fusion protein in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res 1998583542–3546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taulli R, Scuoppo C, Bersani F.et al Validation of met as a therapeutic target in alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res 2006664742–4749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharp R, Recio J A, Jhappan C.et al Synergism between INK4a/ARF inactivation and aberrant HGF/SF signaling in rhabdomyosarcomagenesis. Nat Med 200281276–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smolen G A, Sordella R, Muir B.et al Amplification of MET may identify a subset of cancers with extreme sensitivity to the selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor PHA‐665752. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 20061032316–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weber‐Hall S, Anderson J, McManus A.et al Gains, losses, and amplification of genomic material in rhabdomyosarcoma analyzed by comparative genomic hybridization. Cancer Res 1996563220–3224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bridge J A, Liu J, Qualman S J.et al Genomic gains and losses are similar in genetic and histologic subsets of rhabdomyosarcoma, whereas amplification predominates in embryonal with anaplasia and alveolar subtypes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 200233310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Driman D, Thorner P S, Greenberg M L.et al MYCN gene amplification in rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer 1994732231–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williamson D, Lu Y J, Gordon T.et al Relationship between MYCN copy number and expression in rhabdomyosarcomas and correlation with adverse prognosis in the alveolar subtype. J Clin Oncol 200523880–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morgenstern D A, Anderson J. MYCN deregulation as a potential target for novel therapies in rhabdomyosarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 20066217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scrable H J, Witte D P, Lampkin B C.et al Chromosomal localization of the human rhabdomyosarcoma locus by mitotic recombination mapping. Nature 1987329645–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feinberg A P. Genomic imprinting and gene activation in cancer. Nat Genet 19934110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu Y J, Williamson D, Wang R.et al Expression profiling targeting chromosomes for tumor classification and prediction of clinical behavior. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 200338207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davicioni E, Finckenstein F G, Shahbazian V.et al Identification of a PAX‐FKHR gene expression signature that defines molecular classes and determines the prognosis of alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas. Cancer Res 2006666936–6946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Delattre O, Zucman J, Melot T.et al The Ewing family of tumors—a subgroup of small‐round‐cell tumors defined by specific chimeric transcripts. N Engl J Med 1994331294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bailly R A, Bosselut R, Zucman J.et al DNA‐binding and transcriptional activation properties of the EWS‐FLI‐1 fusion protein resulting from the t(11;22) translocation in Ewing sarcoma. Mol Cell Biol 1994143230–3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sorensen P H, Lessnick S L, Lopez‐Terrada D.et al A second Ewing's sarcoma translocation, t(21;22), fuses the EWS gene to another ETS‐family transcription factor, ERG. Nat Genet 19946146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Alava E, Panizo A, Antonescu C R.et al Association of EWS‐FLI1 type 1 fusion with lower proliferative rate in Ewing's sarcoma. Am J Pathol 2000156849–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zoubek A, Dockhorn‐Dworniczak B, Delattre O.et al Does expression of different EWS chimeric transcripts define clinically distinct risk groups of Ewing tumor patients? J Clin Oncol 1996141245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riley R D, Burchill S A, Abrams K R.et al A systematic review of molecular and biological markers in tumours of the Ewing's sarcoma family. Eur J Cancer 20033919–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin P P, Brody R I, Hamelin A C.et al Differential transactivation by alternative EWS‐FLI1 fusion proteins correlates with clinical heterogeneity in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Res 1999591428–1432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ginsberg J P, de Alava E, Ladanyi M.et al EWS‐FLI1 and EWS‐ERG gene fusions are associated with similar clinical phenotypes in Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 1999171809–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.May W A, Gishizky M L, Lessnick S L.et al Ewing sarcoma 11;22 translocation produces a chimeric transcription factor that requires the DNA‐binding domain encoded by FLI1 for transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993905752–5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chan D, Wilson T J, Xu D.et al Transformation induced by Ewing's sarcoma associated EWS/FLI‐1 is suppressed by KRAB/FLI‐1. Br J Cancer 200388137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang H Y, Illei P B, Zhao Z.et al Ewing sarcomas with p53 mutation or p16/p14ARF homozygous deletion: a highly lethal subset associated with poor chemoresponse. J Clin Oncol 200523548–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ohali A, Avigad S, Zaizov R.et al Prediction of high risk Ewing's sarcoma by gene expression profiling. Oncogene 2004238997–9006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Girnita L, Girnita A, Wang M.et al A link between basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and EWS/FLI‐1 in Ewing's sarcoma cells. Oncogene 2000194298–4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jaboin J, Wild J, Hamidi H.et al MS‐27‐275, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase, has marked in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against pediatric solid tumors. Cancer Res 2002626108–6115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hidalgo M, Rowinsky E K. The rapamycin‐sensitive signal transduction pathway as a target for cancer therapy. Oncogene 2000196680–6686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prieur A, Tirode F, Cohen P.et al EWS/FLI‐1 silencing and gene profiling of Ewing cells reveal downstream oncogenic pathways and a crucial role for repression of insulin‐like growth factor binding protein 3. Mol Cell Biol 2004247275–7283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Benini S, Zuntini M, Manara M C.et al Insulin‐like growth factor binding protein 3 as an anticancer molecule in Ewing's sarcoma. Int J Cancer 20061191039–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toretsky J A, Steinberg S M, Thakar M.et al Insulin‐like growth factor type 1 (IGF‐1) and IGF binding protein‐3 in patients with Ewing sarcoma family of tumors. Cancer 2001922941–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gerald W L, Haber D A. The EWS‐WT1 gene fusion in desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Semin Cancer Biol 200515197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lal D R, Su W T, Wolden S L.et al Results of multimodal treatment for desmoplastic small round cell tumors. J Pediatr Surg 200540251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Werner H, Idelman G, Rubinstein M.et al A novel EWS‐WT1 gene fusion product in desmoplastic small round cell tumor is a potent transactivator of the insulin‐like growth factor‐I receptor (IGF‐IR) gene. Cancer Lett 200724784–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Antonescu C R, Gerald W L, Magid M S.et al Molecular variants of the EWS‐WT1 gene fusion in desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Diagn Mol Pathol 1998724–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shimizu Y, Mitsui T, Kawakami T.et al Novel breakpoints of the EWS gene and the WT1 gene in a desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 1998106156–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reynolds P A, Smolen G A, Palmer R E.et al Identification of a DNA‐binding site and transcriptional target for the EWS‐WT1(+KTS) oncoprotein. Genes Dev 2003172094–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee S B, Kolquist K A, Nichols K.et al The EWS‐WT1 translocation product induces PDGFA in desmoplastic small round‐cell tumour. Nat Genet 199717309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Adamson P C, Blaney S M, Widemann B C.et al Pediatric phase I trial and pharmacokinetic study of the platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor pathway inhibitor SU101. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 200453482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chung E B. Pitfalls in diagnosing benign soft tissue tumors in infancy and childhood. Pathol Annu. 1985;20(Pt 2)323–386. [PubMed]

- 88.Shmookler B M, Enzinger F M, Weiss S W. Giant cell fibroblastoma. A juvenile form of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cancer 1989642154–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McArthur G A, Demetri G D, van Oosterom A.et al Molecular and clinical analysis of locally advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans treated with imatinib: Imatinib Target Exploration Consortium Study B2225. J Clin Oncol 200523866–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Price V E, Fletcher J A, Zielenska M.et al Imatinib mesylate: an attractive alternative in young children with large, surgically challenging dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Pediatr Blood Cancer 200544511–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McArthur G A. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: a surgical disease with a molecular savior. Curr Opin Oncol 200618341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bergh P, Meis‐Kindblom J M, Gherlinzoni F.et al Synovial sarcoma: identification of low and high risk groups. Cancer 1999852596–2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Turc‐Carel C, Dal Cin P, Limon J.et al Involvement of chromosome X in primary cytogenetic change in human neoplasia: nonrandom translocation in synovial sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987841981–1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Crew A J, Clark J, Fisher C.et al Fusion of SYT to two genes, SSX1 and SSX2, encoding proteins with homology to the Kruppel‐associated box in human synovial sarcoma. Embo J 1995142333–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Agus V, Tamborini E, Mezzelani A.et al Re: A novel fusion gene, SYT‐SSX4, in synovial sarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001931347–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nilsson G, Skytting B, Xie Y.et al The SYT‐SSX1 variant of synovial sarcoma is associated with a high rate of tumor cell proliferation and poor clinical outcome. Cancer Res 1999593180–3184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kawai A, Woodruff J, Healey J H.et al SYT‐SSX gene fusion as a determinant of morphology and prognosis in synovial sarcoma. N Engl J Med 1998338153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Albritton K H, Randall R L. Prospects for targeted therapy of synovial sarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 200527219–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Guillou L, Benhattar J, Bonichon F.et al Histologic grade, but not SYT‐SSX fusion type, is an important prognostic factor in patients with synovial sarcoma: a multicenter, retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol 2004224040–4050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xie Y, Tornkvist M, Aalto Y.et al Gene expression profile by blocking the SYT‐SSX fusion gene in synovial sarcoma cells. Identification of XRCC4 as a putative SYT‐SSX target gene. Oncogene 2003227628–7631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sato Y, Nabeta Y, Tsukahara T.et al Detection and induction of CTLs specific for SYT‐SSX‐derived peptides in HLA‐A24(+) patients with synovial sarcoma. J Immunol 20021691611–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kawaguchi S, Wada T, Ida K.et al Phase I vaccination trial of SYT‐SSX junction peptide in patients with disseminated synovial sarcoma. J Transl Med 200531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Antonescu C R, Leung D H, Dudas M.et al Alterations of cell cycle regulators in localized synovial sarcoma: a multifactorial study with prognostic implications. Am J Pathol 2000156977–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mancuso T, Mezzelani A, Riva C.et al Analysis of SYT‐SSX fusion transcripts and bcl‐2 expression and phosphorylation status in synovial sarcoma. Lab Invest 200080805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thomas D G, Giordano T J, Sanders D.et al Expression of receptor tyrosine kinases epidermal growth factor receptor and HER‐2/neu in synovial sarcoma. Cancer 2005103830–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Blay J Y, Ray‐Coquard I, Alberti L.et al Targeting other abnormal signaling pathways in sarcoma: EGFR in synovial sarcomas, PPAR‐gamma in liposarcomas. Cancer Treat Res 2004120151–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Allander S V, Illei P B, Chen Y.et al Expression profiling of synovial sarcoma by cDNA microarrays: association of ERBB2, IGFBP2, and ELF3 with epithelial differentiation. Am J Pathol 20021611587–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. www.clinicaltrials.gov

- 109.Hall P A, Going J J. Predicting the future: a critical appraisal of cancer prognosis studies. Histopathology 199935489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. http://www.weichteilsarkome‐itz.de/Einzelstudien/Studie_EURO_EWING99.htm