Abstract

Aim

To study the correlation between integrity of the photoreceptor layer after resolution of macular oedema (MO) associated with branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) and final visual acuity (VA), and to determine prognostic factors for visual outcome.

Methods

We retrospectively studied 46 eyes from 46 patients with resolved MO secondary to BRVO, the foveal thickness of which was less than 250 µm at final observation. We assessed the status of the third high reflectance band (HRB) in the fovea using optical coherence tomography (OCT) at final observation, and studied OCT images taken at the initial visit in the hope of identifying a factor that would be prognostic of visual outcome.

Results

No differences were found in initial VA or in foveal thickness between eyes with or without complete third HRB at final observation. However, final VA in eyes without a complete HRB was significantly poorer (p<0.002). Additionally, initial status of the third HRB in the parafoveal area of unaffected retina was associated with final VA; lack of visualisation of the third HRB at 500 µm (p = 0.0104) or 1000 µm (p = 0.0167) from the fovea on initial OCT images was associated with poor visual recovery after resolution of the MO.

Conclusion

Integrity of the photoreceptor layer in the fovea is associated with VA in resolved MO, and status of the third HRB before treatment might be predictive of visual outcome.

Macular oedema (MO) is the major cause of visual disturbance associated with branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO).1,2 To date, various treatments have been reported to be effective in reducing MO associated with BRVO, such as grid laser photocoagulation,1,3,4,5 pars plana vitrectomy combined with internal limiting membrane peeling6 or arteriovenous sheathotomy,7 and intravitreal injections of triamcinolone acetonide8,9,10,11 or bevacizumab.12 After successful treatment, resolution of MO often leads to substantial improvement in visual acuity (VA).1,3,4,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 Some patients, however, have a poor visual outcome despite complete resolution of the MO.13

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is now used widely to measure quantitatively the retinal thickness in order to monitor the effectiveness of therapy and to confirm resolution of MO.14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 With high resolution and contrast, OCT allows us to evaluate also the status of the third high reflectance band (HRB), which has been reported to show reflection derived from the junction between inner and outer segments of the photoreceptors.15,16,17 Because several investigators have reported that the status of the third HRB in the fovea is related closely to VA in eyes with retinitis pigmentosa17 or resolved central serous chorioretinopathy,18,19 it is attracting a great deal of attention as a possible marker of the integrity of the photoreceptor layer.

Investigators from our laboratory recently reported that, in eyes with BRVO, the integrity of the third HRB is associated with final VA after resolution of MO brought about by treatment with an intravitreal injection of tissue plasminogen activator.14 To achieve good visual recovery, restoration of the structure of the photoreceptors to a more physiologic condition would be needed, and not merely reduction of the foveal thickness. In our previous report, however, we did not provide information on the status of the third HRB before treatment. In the current work, we studied the correlation between status of the third HRB and VA in eyes with resolved MO secondary to BRVO. In addition, we studied the status of the third HRB in the foveal region before treatment and assessed the prognostic factors related to vision after resolution of MO.

Patients and methods

For this retrospective study, we reviewed the medical records of 46 eyes from 46 patients who had resolved MO associated with BRVO in which the foveal thickness was less than 250 µm at final observation. All patients previously had a visual disturbance due to MO associated with BRVO, and had follow‐up of more than 6 months. The ages of the 46 patients (19 men and 27 women) ranged from 55 to 82 years (mean (SD) 69.7 (7.4) years). In these 46 eyes, treatments to resolve the MO were as follows: 30 eyes were treated with grid laser photocoagulation, 15 eyes underwent pars plana vitrectomy and 9 eyes received intravitreal or posterior sub‐Tenon injections of triamcinolone acetonide. In 19 eyes, a combination of two or more treatments was performed. Eyes treated with tissue plasminogen activator were not included in the current study. For this retrospective study, Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee approval was not required.

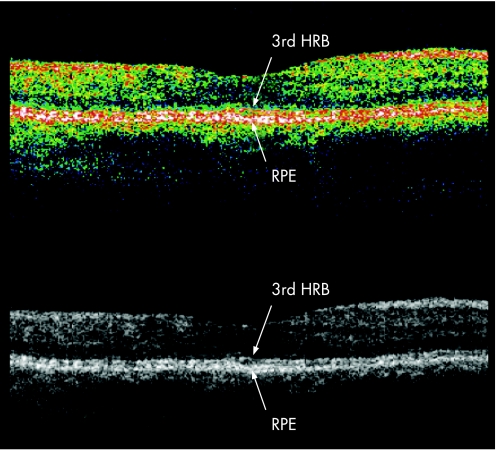

In all patients, OCT examination at final observation was performed with a third‐generation OCT (OCT3; Stratus model 3000, Carl Zeiss, Dublin, California, USA). In most eyes, vertical cross‐section OCT scans (5 mm in length) centred on the fovea were used. Integrity of the photoreceptor layer after resolution of MO was examined by evaluating the status of the third HRB.15,16,17 On OCT imaging, the third HRB was identified as a distinct band just above the high reflectance layer of the retinal pigment epithelium‐choriocapillaris complex, and in greyscale mode could be detected more readily (fig 1).14 Accordingly, we evaluated the status of the third HRB using the greyscale raw image obtained with the OCT3. In the current study, the evaluation was performed in an unmasked fashion.

Figure 1 Sectional retinal images of vertical scan of fovea obtained with optical coherence tomography (OCT3; Stratus model 3000) after resolution of macular oedema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). (A) Pseudocolour OCT image. (B) Monochromatic OCT image. Retina affected by BRVO is shown on the left side of the images. The third high reflectance band (HRB) can be identified more clearly in the monochromatic (greyscale) OCT image. RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

At the initial visit, 29 of the 46 eyes were imaged with the OCT3; the other 17 patients were examined with an older version OCT. In the 29 eyes examined with the OCT3, and using greyscale raw images, we examined whether or not the third HRB was detected in the fovea at the initial observation visit. Unfortunately, it was often difficult to determine the status of the foveal third HRB at the initial visit due to retinal thickening and fresh retinal haemorrhage. We also evaluated the status of the third HRB at points 500, 1000 and 1500 µm vertically from the fovea, toward the unaffected side of the retina. We investigated the correlation between integrity of the third HRB at the initial visit and the final status of the third HRB in the fovea or visual outcome.

All best‐corrected VA measurements were converted to logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) equivalents. All values are presented as mean (SD). VA and the foveal thickness of eyes with and without the third HRB were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test and the Wilcoxon signed‐rank test. We studied the correlation between the third HRB status at the initial visit and the final VA using the X2 test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

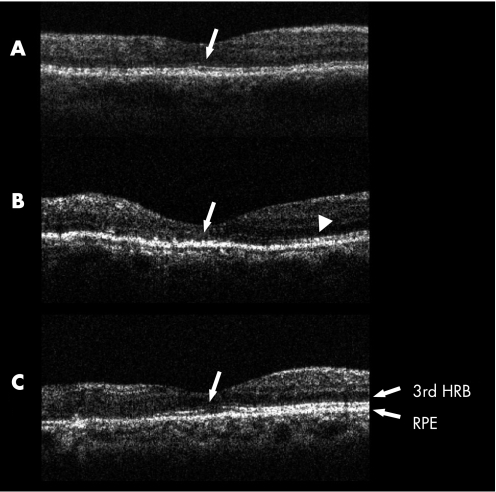

At the final observation visit, 21 eyes (46%) showed a complete third HRB in the fovea (HRB(+) group), while 25 eyes (54%) showed a lack of or an incomplete third HRB in the fovea (HRB(−) group); 16 of the latter 25 (64%) had no third HRB in the fovea, and 9 of the 25 (36%) had a discontinuous third HRB (fig 2).

Figure 2 Optical coherence tomography (OCT) images of vertical retinal sections of the fovea obtained at the final visit. Macular oedema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) is resolved completely in all images. The retina affected by BRVO is shown on the left in all images. Status of the third high reflectance band (HRB) was evaluated with monochromatic (greyscale) OCT images. (A) The third HRB is well preserved in the fovea (arrow). (B) The third HRB is well preserved in the unaffected retina (arrowhead), but is deteriorated in the fovea (arrow) and affected retina. (C) The third HRB is discontinuous in the fovea (arrow), while it is clearly detected in unaffected retina. RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the two groups. At the initial visit, no statistically significant differences were found in age or in foveal thickness. Mean VA at the initial visit was somewhat poorer in the HRB(−) group than in the HRB(+) group, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.092). At the final visit, mean foveal thickness in both groups had decreased significantly, but there was no statistically significant difference in final foveal thickness between the two groups. In accordance with the reduction of retinal thickness, the mean final VA in both groups improved significantly (p<0.001 in each group). Final VA in the HRB(+) group, however, was significantly better than that in the HRB(−) group (p<0.001).

Table 1 Patient characteristics by integrity of the third HRB at the final visit.

| HRB(+) n = 21 | HRB(−) n = 25 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.9 (7.8) | 69.6 (7.1) | 0.733 |

| Gender (men/women) | 12/9 | 7/18 | 0.046 |

| Systemic hypertension | 12 | 13 | 0.897 |

| LogMAR VA at initial visit | 0.40 (0.34) | 0.55 (0.35) | 0.092 |

| Foveal thickness at initial visit (μm) | 466 (129) | 516 (165) | 0.453 |

| Duration of symptoms before first treatment (months) | 3.0 (1.7) | 4.4 (3.6) | 0.309 |

| LogMAR VA at final visit | 0.05 (0.13) | 0.32 (0.29) | <0.001 |

| Foveal thickness at final visit (μm) | 198 (32) | 182 (32) | 0.082 |

| Duration of follow‐up (months) | 25.9 (19.7) | 20.8 (14.8) | 0.326 |

| Duration of persistent MO (months) | 10.4 (5.5) | 15.0 (11.9) | 0.078 |

HRB, high reflectance band; HRB(+), eyes with third HRB in the fovea; HRB(−), eyes without third HRB; logMAR, logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; VA, visual acuity; MO, macular oedema.

In the study described herein, 29 eyes from 29 patients with MO secondary to BRVO were examined with the OCT3 at the initial visit. We next studied the initial status of the foveal third HRB in these eyes. The third HRB could only be detected completely in the fovea in 4 (14%) of the 29 eyes at the initial visit. In the other 25 eyes that did not show a complete third HRB in the fovea at the initial examination, 9 (36%) showed a complete third HRB at the final visit (table 2), and 14 (56%) had a final VA of at least 20/32 (table 3). Initial status of the third HRB in the fovea was not prognostic of either the final status of the foveal third HRB or of visual outcome.

Table 2 Correlation between status of third HRB at initial visit examined at 500, 1000 and 1500 µm from fovea and final status of third HRB.

| Third HRB status at initial visit | Third HRB status at final visit | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRB(+) | HRB(−) | ||

| In fovea: | |||

| Present | 3 | 1 | |

| Absent | 9 | 16 | 0.141 |

| At 500 µm from fovea: | |||

| Present | 10 | 2 | |

| Absent | 2 | 15 | <0.001 |

| At 1000 µm from fovea: | |||

| Present | 11 | 9 | |

| Absent | 1 | 8 | 0.0033 |

| At 1500 µm from fovea: | |||

| Present | 12 | 15 | |

| Absent | 0 | 2 | 0.218 |

HRB(+), eyes with third high reflectance band (HRB) in the fovea; HRB(−), eyes without third HRB in the fovea.

Table 3 Correlation between status of third HRB at initial visit examined at 500, 1000 and 1500 µm from fovea and final VA.

| Third HRB status at initial visit | VA at final visit | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ⩾20/32 | <20/32 | ||

| In the fovea: | |||

| Present | 2 | 2 | |

| Absent | 14 | 11 | 0.823 |

| At 500 µm from fovea: | |||

| Present | 10 | 2 | |

| Absent | 6 | 11 | 0.0104 |

| At 1000 µm from fovea: | |||

| Present | 14 | 6 | |

| Absent | 2 | 7 | 0.0167 |

| At 1500 µm from fovea: | |||

| Present | 16 | 11 | |

| Absent | 0 | 2 | 0.104 |

VA, visual acuity; HRB(+), eyes with third high reflectance band (HRB) in the fovea; HRB(−), eyes without third HRB in the fovea.

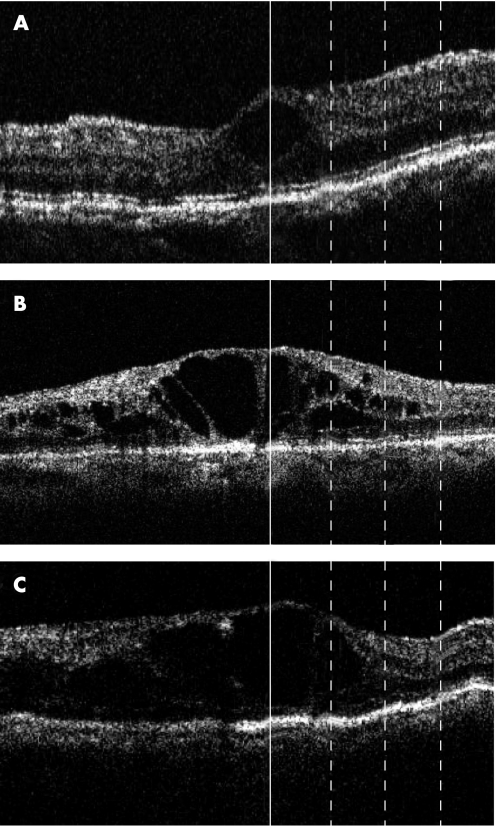

In eyes that had OCT3 images taken at the initial visit, we further evaluated the status of the third HRB at points 500, 1000 and 1500 µm vertically from the fovea, toward the unaffected side of the retina (fig 3), with the hope of predicting final status of the third HRB in the fovea and final VA. At a point 500 µm from the fovea, initial OCT3 images showed a complete third HRB in 12/29 eyes (41%) and an incomplete third HRB in 17/29 (59%) eyes (fig 4). Of the 12 eyes with a complete third HRB at the initial visit, 10 (83%) had a complete third HRB in the fovea at the last examination. In the 17 eyes with incomplete or no third HRB at the initial visit, 15 (88%) never showed a complete third HRB (p<0.001). In the same 12 eyes with a complete third HRB at the first visit, 10 (83%) had vision of 20/32 at the final visit, while of the 17 eyes with an incomplete third HRB at the first visit, only 6 (35%) had a final VA of 20/32 (p = 0.0104).

Figure 3 Monochromatic (greyscale) images of optical coherence tomography (OCT) obtained at the initial visit. All images show macular oedema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). The retina affected by BRVO is on the left in all images. The vertical line at the centre of each image represents the location of the fovea. The three dotted lines represent points at 500, 1000 and 1500 µm from the fovea, from the left, respectively. (A) The third high reflectance band (HRB) is clearly visible at all points. (B) The third HRB is not detected beneath the fovea or at 500 µm from the fovea, but does appear at the 1000 µm and 1500 µm points. (C) The third HRB can be detected only at 1500 µm from the fovea.

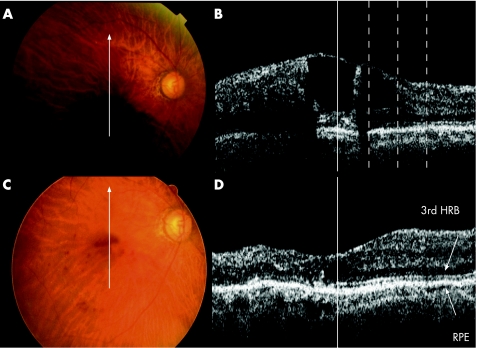

Figure 4 An 82‐year‐old woman with branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) accompanied by macular oedema (MO) with a 1‐month history of decreased visual acuity in the right eye, which was 20/50 at the initial visit. (A) Fundus photograph shows extensive retinal haemorrhage associated with BRVO. (B) Monochromatic optical coherence tomography (OCT) image of the fovea was made at the initial visit. The vertical solid line represents the location of the fovea. The three dotted lines represent points 500, 1000 and 1500 µm from the fovea, from the left, respectively. MO was prominent with large cystoid spaces and a foveal thickness of 464 µm. The third HRB cannot be detected in the fovea but is well visualised at other measurement points. The patient was treated with grid laser photocoagulation in the right eye. (C) Fundus photograph at the final visit shows minimal retinal haemorrhage. (D) OCT image at the final visit shows the MO to be completely resolved. Foveal thickness is now 165 µm. The third HRB is well preserved in the fovea and visual acuity was 20/25. The vertical solid line represents the location of the fovea.

Similarly, at a point 1000 µm from fovea, initial OCT3 images showed a complete third HRB in 20/29 (69%) eyes and an incomplete third HRB in 9/29 (31%) eyes. Initial status of the HRB at a point 1000 µm from the fovea correlated significantly with the final HRB status at the fovea (p = 0.0033) and with visual outcome (p = 0.0167). However, at a point 1500 µm from fovea, the third HRB was detected completely in 27 (93%) of 29 eyes. This detection was not correlated with final HRB status in the fovea or with visual outcome (p = 0.218 and p = 0.104).

Discussion

MO associated with BRVO appears as a thickening of the sensory retina due to leakage from the affected retinal capillaries. To date, various treatments have been reported to successfully reduce the retinal thickening and restore foveal function.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 It is generally believed that the decrease in foveal thickness is what leads to improvement in VA.1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 In a clinical setting, however, some patients achieve only poor or limited improvement in VA despite complete resolution of the MO.14 Although foveal thickness in all eyes in the current study was less than 250 µm, final VA after resolution of the MO ranged from 20/200 to 20/16. The reasons for this marked variance in final VA is controversial, but integrity of the foveal photoreceptor layer might explain the difference in final VA after resolution of MO.

OCT has recently become a part of routine clinical examination of patients with macular disease, and allows us to evaluate the morphologic changes that take place in MO.14,17,20,21,22,23,24,25 In a recent report, Costa et al15 suggested the significance of two highly reflective layers at the level of the outer retina in OCT images. They suggested that the inner layer, which is identical to the third HRB reported in the current study, could not be detected in damaged outer retina. Similarly, Sandberg et al17 reported that decreased VA in eyes with retinitis pigmentosa is associated with declining visualisation of the third HRB in the fovea. In eyes with central serous chorioretinopathy, Eandi et al18 and Piccolino et al19 reported that changes within the foveal photoreceptor layer were associated with decreased vision. Based on previous reports and on our findings,14,15,17,18,19 integrity of the foveal retinal photoreceptor layer is associated with good VA, while incomplete visualisation of the third HRB in the fovea could suggest deterioration or disorganisation of photoreceptor cells.

In the current study, status of the third HRB of the 46 eyes was assessed after resolution of MO. While all eyes showed a reduction in foveal thickness (to less than 250 µm) at the final visit, VA in eyes with an incomplete or no third HRB remained poor. Recently, we reported a similar correlation between status of the third HRB and VA in BRVO‐induced MO treated with an intravitreal injection of tissue plasminogen activator.14 The reasons why the final status of the third HRB varies from eye to eye remain unclear. It is possible that more severe ischaemia in the foveal photoreceptor cells during the acute or chronic phase of BRVO might lead to significant photoreceptor cell death, resulting in the lack of the third HRB. It is also possible that more severe swelling in the foveal photoreceptor layer during the acute phase of BRVO might result in significant disarrangement of photoreceptor cells even after resolution of the MO. In such a disarranged photoreceptor layer, the third HRB might not be detected as a reflective line.

It would be of great value to be able to predict, before treatment, final integrity of the photoreceptor layer and visual outcome. In the current study, we evaluated the status of the third HRB before treatment, and in only 4 of 29 eyes could the third HRB be detected in the foveal region at the initial patient visit. It is possible that the severe retinal haemorrhage and thickened neurosensory retina due to the leakage from BRVO weakened the signal intensity of the outer retinal layers, making it impossible to detect reflection from the junction of inner and outer segments. It is also possible that the photoreceptor layer is swollen due to leakage from the affected capillaries, so the improper alignment of inner/outer segments could not be detected as a reflective line. Histologic reports seem to support the second explanation, as cystoid spaces in MO associated with BRVO have reportedly been seen often in the outer nuclear and plexiform layers, and extensive MO often affects the photoreceptor layer in the fovea, with resultant photoreceptor dysfunction and cell loss.26 We could not make this determination, however, due to the limitations of OCT3 imaging.

MO due to BRVO extends often to unaffected retina beyond the fovea as the leakage from the affected capillaries becomes severe. While the fovea is often blocked with fresh retinal haemorrhage, only limited haemorrhage extends to the unaffected retina. Accordingly, in an attempt to predict the final status of the foveal photoreceptor layer and visual outcome, we examined the initial status of the third HRB at points 500, 1000 and 1500 µm vertically from the fovea and progressing toward the unaffected portion of retina. When leakage from the capillaries in the affected area was severe, retinal swelling often extended to some of the evaluation points in unaffected portions of the retina. Based upon evaluation of many OCT images, this extension of retinal swelling is seen primarily in the outer retina. The photoreceptor layer is swollen due to leakage from the affected capillaries, so the improper alignment of inner/outer segments could not be detected as a reflective line. In such cases, the foveal photoreceptor layer might be affected severely at the initial visit, resulting in an incomplete third HRB even after resolution of MO—and poor visual outcome.

Limitations of the current study are its retrospective nature and small sample size. Our findings suggest, however, that OCT images could provide information on the foveal photoreceptor layer and visual prognosis in eyes with resolved MO associated with BRVO by use of the third HRB as a landmark. Although the initial status of the third HRB in the fovea could not be evaluated due to retinal haemorrhage, we can assume the final status of the third HRB in the fovea from the initial status of the parafoveal third HRB. The current study showed that resolution of MO leads in many cases to significant improvement in VA. However, when the third HRB in the parafoveal region is incomplete at the initial visit, visual recovery, even after successful treatment of the MO, could still be limited. Further prospective studies, especially with the use of high resolution images of Fourier‐domain OCT, are necessary to elucidate which eyes with MO associated with BRVO can be expected to have marked improvement in VA after resolution of the MO.

Abbreviations

BRVO - branch retinal vein occlusion

HRB - high reflectance band

MO - macular oedema

OCT - optical coherence tomography

RPE - retinal pigment epithelium

VA - visual acuity

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.The Branch Vein Occlusion Study Group Argon laser photocoagulation for macular edema in branch vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 198498271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glacet‐Bernard A, Coscas G, Chabanel A.et al Prognostic factors for retinal vein occlusion: prospective study of 175 cases. Ophthalmology 1996103551–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esrick E, Subramanian M L, Heier J S.et al Multiple laser treatments for macular edema attributable to branch retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2005139653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohashi H, Oh H, Nishiwaki H.et al Delayed absorption of macular edema accompanying serous retinal detachment after grid laser treatment in patients with branch retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 20041112050–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnarsson A, Stefansson E. Laser treatment and the mechanism of edema reduction in branch retinal vein occlusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200041877–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandelcorn M S, Nrusimhadevara R K. Internal limiting membrane peeling for decompression of macular edema in retinal vein occlusion: a report of 14 cases. Retina 200424348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horio N, Horiguchi M. Effect of arteriovenous sheathotomy on retinal blood flow and macular edema in patients with branch retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2005139739–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsujikawa A, Fujihara M, Iwawaki T.et al Triamcinolone acetonide with vitrectomy for treatment of macular edema associated with branch retinal vein occlusion. Retina 200525861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karacorlu M, Ozdemir H, Karacorlu S A. Resolution of serous macular detachment after intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide treatment of patients with branch retinal vein occlusion. Retina 200525856–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cekic O, Chang S, Tseng J J.et al Intravitreal triamcinolone injection for treatment of macular edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion. Retina 200525851–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen S D, Sundaram V, Lochhead J.et al Intravitreal triamcinolone for the treatment of ischemic macular edema associated with branch retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2006141876–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iturralde D, Spaide R F, Meyerle C B.et al Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment of macular edema in central retinal vein occlusion: a short‐term study. Retina 200626279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murakami T, Takagi H, Kita M.et al Intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator to treat macular edema associated with branch retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2006142318–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murakami T, Tsujikawa A, Ohta M.et al Photoreceptor status after resolved macular edema in branch retinal vein occlusion treated with tissue plasminogen activator. Am J Ophthalmol 2007143171–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa R A, Calucci D, Skaf M.et al Optical coherence tomography 3: automatic delineation of the outer neural retinal boundary and its influence on retinal thickness measurements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004452399–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen T C, Cense B, Miller J W.et al Histologic correlation of in vivo optical coherence tomography images of the human retina. Am J Ophthalmol 20061411165–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandberg M A, Brockhurst R J, Gaudio A R.et al The association between visual acuity and central retinal thickness in retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005463349–3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eandi C M, Chung J E, Cardillo‐Piccolino F.et al Optical coherence tomography in unilateral resolved central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina 200525417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piccolino F C, de la Longrais R R, Ravera G.et al The foveal photoreceptor layer and visual acuity loss in central serous chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 200513987–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spaide R F, Lee J K, Klancnik J K., Jret al Optical coherence tomography of branch retinal vein occlusion. Retina 200323343–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lerche R C, Schaudig U, Scholz F.et al Structural changes of the retina in retinal vein occlusion – imaging and quantification with optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 200132272–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozdek S C, Erdinc M A, Gurelik G.et al Optical coherence tomographic assessment of diabetic macular edema: comparison with fluorescein angiographic and clinical findings. Ophthalmologica 200521986–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antcliff R J, Stanford M R, Chauhan D S.et al Comparison between optical coherence tomography and fundus fluorescein angiography for the detection of cystoid macular edema in patients with uveitis. Ophthalmology 2000107593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markomichelakis N N, Halkiadakis I, Pantelia E.et al Patterns of macular edema in patients with uveitis: qualitative and quantitative assessment using optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 2004111946–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voo I, Mavrofrides E C, Puliafito C A. Clinical applications of optical coherence tomography for the diagnosis and management of macular diseases. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 20041721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tso M O M. Pathology of cystoid macular edema. Ophthalmology 198289902–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]