Abstract

Objective

To calculate the best possible estimates for age specific life expectancy (LE) and anticipated age at the time of death (AAD) in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) compared with the general population in the UK. These may be of greater value to patients than standardised mortality ratios (SMRs), which are usually reported in studies on mortality in PD.

Methods

A literature review identified articles with data on age stratified life expectancy or SMRs to calculate estimations of LE using the Gompertz function and data on mortality and LE in the UK from the Office of National Statistics and Actuarial Department for the year 2003.

Results

Two UK studies and four from Western Europe were used to estimate LE and AAD for patients with PD from SMRs. The mean LEs of patients with PD compared with the general population were: 38 (SD 5) years for onset between 25 and 39 years compared with 49 (SD 5) years; 21 (SD 5) years for onset between 40 and 64 years compared with 31 (SD 7) years; and 5 (SD 4) years for onset age ⩾65 years compared with 9 (SD 5) years. The average AAD of patients with PD with onset between 25 and 39 years was 71 (SD 3) years and considerably lower than that of the general population (82 (SD 2) years). The difference between average AAD for older individuals with PD (onset ⩾65 years) and the general population was smaller, with an AAD of approximately 88 (SD 7) years compared with 91 (SD 5) years.

Conclusions

The calculations showed that LE and AAD in PD are reduced for all onset ages but this reduction is greatest in individuals with a young onset. While the results are average estimates, these can provide useful indications of LE and AAD.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with an average onset of approximately 60 years, but some patients have a much earlier onset. PD is associated with increased mortality compared with the general population, with an ongoing debate on the influence of dopaminergic treatment on mortality rates.1,2,3,4,5

Although some papers reported survival time,6 comparison of mortality rates between patients with PD and the general population is usually presented using the standardised mortality ratio (SMR). The SMR allows for comparison between population groups with different demographics and life expectancies. This ratio is however of limited value in advising patients and their families on their prognosis. In addition, limited information is available on the comparative general survival and life expectancy in young versus older onset PD.

We therefore undertook an analysis of published data on mortality in PD to calculate estimates of life expectancy (LE; anticipated mean remaining time to live) based on SMRs and the most recent UK actuary data, and to compare LE in patients with PD by age group.

Methods

Searches and data extraction

A PubMed search was conducted in April 2006 for articles published in English using the following search terms: (“Parkinson Disease”[MeSH] OR “Parkinsonian Disorders”[MeSH] OR parkinson*) AND (“Vital Statistics”[MeSH] OR mortality OR survival) NOT “Wolff‐Parkinson‐White Syndrome” [MeSH].

Of the retrieved articles, 54 containing original LE, mortality or survival data were selected for further review. Articles were excluded if they did not provide LE or SMR estimates, or did not use PD diagnosis as the outcome. Studies beginning after 1984 were preferred so that the use of levodopa medication was widespread, as it is now. All articles were evaluated by one of the authors (LI) and data on SMRs, stratified by age or sex, collected. For the analysis of LE compared with the 2003 actuary data, only articles from the UK and, as the number of UK studies reporting age specific data was limited, Western Europe were included.

Statistics

The SMRs from eligible UK and Western European studies were averaged for each age group to provide a single value for Gompertz calculations in each age category (eg, Schrag et al6 and Ben‐Shlomo and Marmot7 had SMRs of 2.1 and 3.9 for ages 25–39 years, and therefore an average SMR of 3 was used for calculations in this age range).

Estimated LE can be calculated from the SMR using a modified Gompertz function.8,9,10,11 The Gompertz equation is based on the observation that mortality rate tends to increase exponentially with age.

Equation 1: μx = B × ekx

is the mortality rate at age x; log (B) (y intercept) and k (slope) are constants from the plot of natural log μx against x.

Equation 2: SMR = 1μx/0μx and 1μx = SMR × B × ekx

where 1μx is the age specific mortality rate for the study population; 0μx is the age specific mortality rate for the standard population.

Equation 3: ex = [ln (1+k/μx) –0.5 (1+μx/k)−2]/k

where ex is the total remaining LE. The constants, B and k were calculated from the age and sex specific mortality rates for England and Wales in 2003 from the Office of National Statistics.

The inverse log of y intercepts log (B) (males = 0.0000320; females = 0.0000142) and slopes k (males = 0.095; females = 0.103) were calculated from the graph of the natural log of the mortality rate against age. The assumption is that the 2003 mortality rates in England and Wales are similar to the present mortality rates. The 2004 mortality rates are still considered provisional, so mortality rates from 2003 are the most recent available. Remaining LEs for men and women were calculated separately using equation 2 and substituting the calculated mortality rate into equation 3.

Using the Gompertz function with an SMR of 1 produces the calculated age specific remaining LEs of the general population, which are similar to the remaining LEs reported by the UK Actuarial Office (eg, for SMR = 1, the LE for men aged 25–29 years is calculated as an average of 54.0 years compared with 52.1 years reported by actuarial data). Using the average SMR per age group from the PD studies produced the calculated LE of patients with PD (eg, with an SMR of 3 the average LE for men aged 25–29 years is 42.6 years). The change in LE for patients with PD was calculated by subtracting the calculated LE in patients with PD from the calculated age specific standard LE (eg, for men aged 25–29 years, 54.0–42.6 = 11.4). These changes were then subtracted from the average LEs that were provided by the Actuarial Office (eg, for men aged 25–29 years, 52.1–11.4 = 40.7 years). The anticipated average age at the time of death (AAD) was calculated by summing the average current age (eg, 27.5 for the range 25–29 years) and the average LE for the age category (eg, for men aged 25–29 years in the general population the average AAD was 27.5+52.1 = 79.6 years, and for those with PD an AAD of 27.5+40.7 = 68.2 years).

Two studies from the UK6,7 and four studies from other European countries12,13,14,15 were eligible for inclusion in the analysis of LE compared with UK population mortality data. A UK case control (CC) study included patients with PD recruited by general practitioners, and their age, sex and practice matched controls. Another UK study6 reported survival and SMRs in young onset patients with PD. The European studies were from Italy,14 Norway,15 France12 and a collaboration of studies from France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and Italy.13 An additional study from Italy was not included as the age groups were too broad.16

As age categories varied between studies and the UK actuary data, the SMRs from each study age group were applied to all relevant 5 year actuarial age groups to calculate changes in LE (eg, a study with age 60–69 years would be used for actuarial age groups 60–64 and 65–69). The same SMRs were used for men and women in the Gompertz equations. Only two of the studies reported mortality rates by age at diagnosis,6,15 and the remaining studies measured mortality rates from the start of the study.

For ages 25–40 years, SMRs from the two UK studies6,7 were used to estimate LE (mean 3.0). The SMR (3.9) from one study7 was used for ages 40–50 years. For ages 50–54 years, the mean SMR (2.5) was calculated from three studies.7,14,15 The SMR (2.3) for ages 55–59 years was estimated from four studies.7,13,14,15 Four studies were used to estimate the mean SMRs for ages 60–64 years (2.2) and 65–74 years (2.0).7,13,14,15 The most extreme SMR (10.0) was disregarded because it was not consistent with the four other values.12 The SMR (3.0) for ages 75–84 years was estimated from five studies,7,12,13,14,15 and for ages 85–89 (3.1) from four studies,7,12,13,14 The SMR for ages 90–99 years was calculated from three of four eligible studies,7,12,13 because one did not specify the SMR for ages over 89 years. Patients over 89 years were infrequent and therefore the estimates were not as robust as for younger age categories. At ages less than 70 years, the UK CC study7 reported the highest SMRs among the studies used for calculations, but above 70 years, the SMR in this study was comparable with other studies. The lowest SMRs were from the Norwegian study.15

Results

Reported standardised mortality ratios from 1935 to 2001

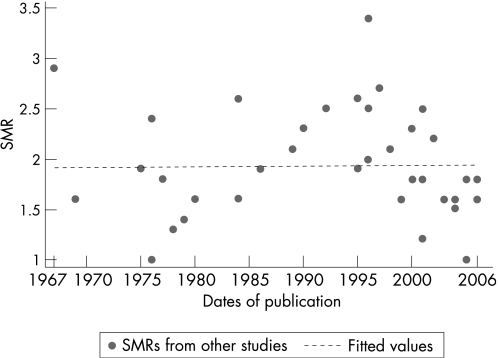

The SMRs or mortality ratios comparing PD cases and controls from 39 studies from 1935 to 2006 are reported in table 1. The SMRs ranged from 1, indicating no differences compared with the general population, to 3.4, indicating more than threefold higher mortality in PD. The time trend of estimates is inconsistent, although there appears to be a decrease in the 1970s, corresponding to the introduction of levodopa trials during that time period (fig 1). A geographical trend is not apparent, as the SMRs within each geographical region are as variable as between regions (table 1).

Table 1 Summary of studies that have reported a standardised mortality ratio, comparing Parkinson's disease patients with a general population.

| Reference/date | No of participants | Location | Study recruitment dates | Overall SMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoehn17 1967 | 241* | USA | 1949–64 | 2.9 |

| Nobrega18 1969 | 203 | USA | 1935–66 | 1.6 |

| Sweet19 1975 | 100† | USA | 1968 | 1.9 |

| Barbeau20 1976 | 80† | Canada | 1968 | 2.4 |

| Diamond1 1976 | 1087 | USA | 1968–69 | 1.0 |

| Zumstein21 1976 | 1155† | NA | 1969–71 | 1.0 |

| Marttila22 1977 | 349† | Finland | 1969–75 | 1.9 |

| Joseph23 1978 | 1625† | USA | 1969 | 1.3 |

| Diamond,24 1979 | 327† | USA | 1972 | 1.4 |

| Rinne25 1980 | 349† | Finland | 1969 | 1.6 |

| Curtis26 1984 | 176† | UK | 1969–72 | 2.6 |

| Rajput27 1984 | 138/276‡ | USA | 1967–79 | 1.6 |

| Cedarbaum28 1987 | 100† | USA | 1968 | 1.9 |

| Diamond29 1989 | 359 | USA | 1968–70 | 2.1 |

| Ebmeier30 1990 | 243 | UK | 1984 | 2.3 |

| Kuroda31 1992 | 438 | Japan | 1978 | 2.5 |

| Ben‐Shlomo 7 1995 | 220/421‡ | UK | 1970–72 | 2.6 |

| Wermuth32 1995 | 458 | Denmark | 1973–91 | 1.9 |

| Bennett33 1996 | 159 | USA | 1982–84 | 2.0 |

| Morens34 1996 | 8006§ | USA | 1965 | 2.5 |

| Tison12 1996 | 24/2768¶ | France | 1988 | 3.4 |

| Louis35 1997 | 154/1254‡ ** | USA | 1988 | 2.7 |

| Schrag6 1998 | 132†† | UK | 1981–98 | 2.1 |

| Hely36 1999 | 149 | Australia | 1984–87 | 1.6 |

| Berger13 2000 | 139/11694‡‡ | Europe | 1987–92 | 2.3 |

| Donnan37 2000 | 97/902† | UK | 1989–95 | 1.8 |

| Morgante14 2000 | 59/118 | Italy | 1987 | 2.3 |

| Guttman38 2001 | 15304/30608‡ §§ | Canada | 1993–94 | 2.5 |

| Lees4 2001 | 782† | UK | 1985–90 | 1.8 |

| Montastruc39 2001 | 58† | France | 1982–89 | 1.2 |

| Parashos40 2002 | 89/89‡ | USA | 1979–88 | 2.2 |

| Elbaz41 2003 | 196/185‡ | USA | 1976–95 | 1.6 |

| Fall42 2003 | 170/510‡ | Sweden | 1989 | 1.6¶¶ |

| Herlofson15 2004 | 245 | Norway | 1993 | 1.5*** |

| Hughes43 2004 | 90/50‡ | UK | 1985–86 | 1.6 |

| de Lau44 2005 | 166/6803‡‡ | Netherlands | 1990–93 | 1.8 |

| Marras5 2005 | 800† | USA and Canada (DATATOP) | 1987–88 | 1.0 |

| D'Amelio16 2006 | 58/116‡ | Italy | 1987 | 1.8 |

| Chen45 2006 | 288/51300§ ‡‡ | USA | 1986–2000 | 1.6 |

NA, not available; PD, Parkinson's disease.

*672 patients with primary parkinsonism with a mean age of 55.3 years, but only 241 were used for mortality calculations.

†Data from a drug clinical trial.

‡Case control study number of cases/number of controls.

§Men only.

¶Population based cohort (n = 2792) with 16 deaths in patients with PD and 605 non‐PD.

**Non‐demented patients with PD compared with controls.

††132 of 139 young onset PD cases (onset aged 21–39 years) had mortality data.

‡‡Cohort study number of cases/total cohort.

§§This study used parkinsonism from records of physician diagnoses or PD drugs as the outcome of interest.

¶¶Cumulative mortality incidence ratio; Cox proportional hazards ratio was 2.4.

***SMR was 1.5 in all 245 identified PD cases, but the SMR was 1.35 in definite PD, 1.42 in definite and probable PD, and 1.99 in possible PD.

Figure 1 Standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) for Parkinson's disease from 39 studies by publication date.

Mean life expectancy in patients with PD compared with the general population

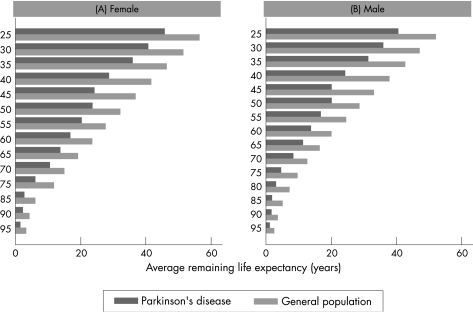

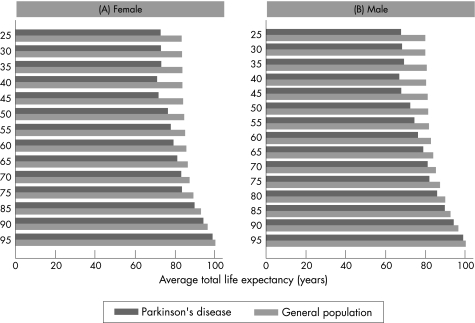

The estimated changes in LE compared with the general population for a range of possible SMR values, stratified by age and sex, using the Gompertz function and the 2003 UK mortality rates, are presented in table 2. Calculated LEs (fig 2) and AAD (fig 3) were compared between patients with PD and the UK general population. The graphical comparisons show that LE and AAD are considerably shorter or earlier in patients with age at onset before 50 years compared with the general UK population. This difference decreases with increasing age in females and males. The mean LE of patients with PD with onset between 25 and 39 years was 38 (SD5) years, corresponding to an AAD of 71 (SD 3) years compared with an LE of 49 (SD 5) and AAD of 82 (SD 2) years in the general population. The mean LE of patients with PD with onset between 40 and 64 years was 21 (SD 5) years, resulting in an AAD of 73 (SD 4) years compared with an LE of 31 (SD7) and an AAD of 83 (SD 2) years in the general population. The mean LE for older individuals with PD (onset ⩾65 years) was 5 (SD 4) years, resulting in an AAD of 88 (SD 7) years compared with an LE of 9 (SD 5) years and an AAD of 91 (SD 5) years in the general population. The SMR calculations were the same for both sexes, and therefore changes in LE were the same, but the actual LE and AAD estimates were higher in women because they live longer, on average, than males in the general population.

Table 2 Estimated changes in life expectancy compared with the general population in years, stratified by age and sex, calculated from specified standardised mortality ratios using the Gompertz function and 2003 UK mortality rates.

| Age (y) | Sex | SMR | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 4.0 | ||

| 20 | Male | 7.3 | 0.0 | −4.2 | −7.2 | −9.6 | −11.5 | −13.1 | −14.5 |

| Female | 6.7 | 0.0 | −3.9 | −6.7 | −8.9 | −10.6 | −12.1 | −13.4 | |

| 30 | Male | 7.2 | 0.0 | −4.2 | −7.2 | −9.5 | −11.3 | −12.9 | −14.2 |

| Female | 6.7 | 0.0 | −3.9 | −6.7 | −8.8 | −10.5 | −12.0 | −13.3 | |

| 40 | Male | 7.1 | 0.0 | −4.1 | −7.0 | −9.2 | −11.0 | −12.4 | −13.7 |

| Female | 6.6 | 0.0 | −3.9 | −6.6 | −8.7 | −10.3 | −11.8 | −13.0 | |

| 50 | Male | 6.9 | 0.0 | −3.9 | −6.6 | −8.6 | −10.1 | −11.3 | −12.5 |

| Female | 6.5 | 0.0 | −3.7 | −6.3 | −8.3 | −9.8 | −11.1 | −12.2 | |

| 60 | Male | 6.4 | 0.0 | −3.4 | −5.7 | −7.3 | −8.6 | −9.6 | −10.4 |

| Female | 6.1 | 0.0 | −3.4 | −5.7 | −7.3 | −8.6 | −9.7 | −10.6 | |

| 70 | Male | 5.3 | 0.0 | −2.6 | −4.3 | −5.4 | −6.3 | −6.9 | −7.5 |

| Female | 5.3 | 0.0 | −2.7 | −4.4 | −5.7 | −6.6 | −7.3 | −7.9 | |

| 80 | Male | 3.9 | 0.0 | −1.8 | −2.8 | −3.5 | −4.0 | −4.4 | −4.8 |

| Female | 3.9 | 0.0 | −1.8 | −2.9 | −3.7 | −4.2 | −4.7 | −5.0 | |

| 90 | Male | 2.5 | 0.0 | −1.1 | −1.7 | −2.1 | −2.4 | −2.6 | −2.7 |

| Female | 2.5 | 0.0 | −1.1 | −1.7 | −2.1 | −2.4 | −2.7 | −2.8 | |

SMR, standardised mortality ratio.

Figure 2 Average remaining life expectancies by age for patients with Parkinson's disease and the 2003 UK population in females and males.

Figure 3 Average anticipated age at death for patients with Parkinson's disease and the 2003 UK population in females and males.

Discussion

The estimates of LE for patients with PD in the UK show that they have a decreased LE compared with the general population within all age groups, but LE is most severely decreased with young age at onset. In patients with onset between 25 and 40 years, SMR estimated average LE was reduced from a mean of 49 to 38 years; in those with onset between 40 and 65 years, average LE was reduced from 31 to 21 years; and in those with an onset at or above 65 years, average LE was reduced from 9 to 5 years. The median time period between onset and death reported in UK young onset cases was 27 years for patients with onset between 36 and 39 years, and 35 years for those with onset between 22 and 35 years.6 These survival estimates are slightly lower than the calculated LE for ages 25–40 years (38 years). However, the median survival times were based only on the 23 deceased of overall 132 patients. The 23 deceased patients may have been biased towards individuals with a worse prognosis, and therefore shorter survival times.

Previous studies have similarly reported increased mortality and greater reduction of LE in patients with younger onset. A US based study41 reported an increasing trend of relative risk according to age of onset with higher mortality in the younger onset cases. Australian,36 French,12 Norwegian15 and UK7 studies had similar findings. In addition, a study of pathologically proven cases of PD reported that, although those with young onset (<40 years) had a 12 years longer mean disease duration to death, mean age at death was 30 years earlier than in those with older onset (>70 years).46 Diamond et al29 found that mortality in young onset (<50 years) patients was non‐significantly greater than in older onset (>59 years) patients. In contrast with these studies were two Italian studies, one which was not used for calculations because age categories were too broad and reported odds ratios of 1.7 in patients with age at onset below 68 years, and 2.0 in those with onset at or above 68 years.14,16

Results from the SMR based calculations were confirmed by comparison with reported survival rates in the analysed studies, and also in other studies. A CC study in the USA41 reported that median survival was 10 years in incident cases compared with 13 years in age matched controls with a median age of 72 years, over a 7–8 year period. The study also reported that median survival in PD individuals with onset from 41 to 66 years was 17 years,41 which is comparable with our calculated mean remaining LE of 21 years. The median survival for patients with PD with onset between 67 and 76 years was 10 years, and for ages 77–97 years, median survival was 6 years.41 In a Dutch study,44 median survival after PD diagnosis at 71 years or older was 9 years, and in a Swedish community study,42 patients with mean onset age of 66 years had mean duration before death of 13 (range 1−47) years. These data are similar to those calculated in our study, although age specific values could not be calculated. The wide range of survival times within and between studies highlights that survival and LE estimates are based on average values, and the actual survival time depends on multiple factors.5,42,43,45,47 Thus the US based DATATOP study5 found similar mortality in patients with PD and controls, and it has been hypothesised that this finding was a result of the selection bias as well as optimised medical care inherent to treatment trials.48 Swedish,42 Norwegian15 and Italian14,16 studies each found a 1 year difference in mean age at death for PD cases compared with age and sex matched controls. These studies consisted mostly of older onset cases, which would be expected to have less difference in LE than young onset patients, compared with the general population in the same age groups. The UK CC study, which included some young onset patients, found that survival from the start of the study was 6.5 years (men) and 6.6 years (women) less in patients with PD than matched controls.7 It is uncertain whether the similar survival between PD cases and controls in some studies was a result of shorter follow‐up time, earlier disease stage, onset age or geographical differences in survival.5,42,43,45,47

While we have no information from our analysis on the causes of the shorter LE in patients with younger onset, it is likely that this is mainly attributable to the longer disease duration in those who develop the first symptoms relatively early in life. It may also be speculated that after a long disease duration, despite slower disease progression in young onset disease, a greater proportion eventually becomes significantly disabled and prone to medical complications. In addition, it is recognised that the underlying aetiology in young onset parkinsonism is more frequently due to genetic and rarer symptomatic causes, than in older onset cases.49 These are often associated with a worse prognosis. In the older onset group, on the other hand, cases of late onset dystonic tremor (diagnosed as “benign tremulous PD”) or of neuroleptic induced parkinsonism, which are likely to carry a better prognosis, may have been erroneously included.

This study has some limitations.

The use of the Gompertz function can only be made if comparing with the same population. Therefore, the UK LE calculations were made using available UK and Western European data. The data are not necessarily transferable to other populations, but this calculation could be repeated for other countries.

Only two6,15 studies that were used for Gompertz calculations provided data on mortality since diagnosis. The majority of studies assessed mortality rates from the start of the study, which may have introduced a bias. SMRs from studies that measured mortality from the start of the study could overestimate mortality in patients with PD, and would most certainly predict shorter LEs than if onset age were used as the starting point.

For the younger age groups from 20 to 54 years, only one or two studies per age group were used to estimate the LE.6,7 The SMR increased in the 75–89 year age group, and was inflated by one figure from the Italian study.14 It would have been desirable to have a larger number of studies reporting SMRs for all age groups to obtain more robust estimates, but additional data were unavailable.

One UK CC study was included even though it began before the specified time period of 1984, because there were no other UK studies in older patients with PD.7

Clinic based studies have the potential for selection bias, as patients selected from tertiary clinics or specialists are likely to be more severe than the average PD patient causing SMR overestimation. On the other hand, controls selected from hospitals are more likely to be ill, with higher mortality than the general population, so the SMR for patients with PD would be underestimated.

The preferred information for LE calculations would be the prospective survival time of newly diagnosed patients with PD, by age group (at onset) and sex. It would also be useful to know whether patients were medicated and to report stratified results to examine whether medication affects survival time. This information is currently limited, and can only be addressed in large prospective studies with long follow‐up, such as the Rotterdam Study,50 European Prospective Investigation of Cancer,51 Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging52 or the Nurses Health Study/Health Professionals Follow‐up study.53 In the future, robust estimates could be provided by these or similar studies.

Finally, the results are average estimates, and while they can provide useful indications of LE, it must be emphasised that survival can vary between patients as a result of other factors.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals.

Web resources

Abbreviations

AAD - anticipated age at the time of death

CC - case control

LE - life expectancy

SMR - standardised mortality ratio

PD - Parkinson's disease

Footnotes

Competing interests: GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals paid for the research for the manuscript. LI's PhD studentship was sponsored by GSK and she is now an employee at GSK. AC is an employee of GSK.

References

- 1.Diamond S G, Markham C H. Present morality in Parkinson's disease: the ratio of observed to expected deaths with a method to calculate expected deaths. J Neural Transm 197638259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lees A J. Comparison of therapeutic effects and mortality data of levodopa and levodopa combined with selegiline in patients with early, mild Parkinson's disease. Parkinson's Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom. BMJ 19953111602–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiRocco A, Molinari S P, Kollmeier B.et al Parkinson's disease: progression and mortality in the L‐DOPA era. Adv Neurol 1996693–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lees A J, Katzenschlager R, Head J.et al Ten‐year follow‐up of three different initial treatments in de‐novo PD: a randomized trial. Neurology 2001571687–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marras C, McDermott M P, Rochon P A.et al Survival in Parkinson disease: thirteen‐year follow‐up of the DATATOP cohort. Neurology 20056487–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrag A, Ben‐Shlomo Y, Brown R.et al Young‐onset Parkinson's disease revisited‐clinical features, natural history, and mortality. Mov Disord 199813885–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben‐Shlomo Y, Marmot M G. Survival and cause of death in a cohort of patients with parkinsonism: possible clues to aetiology? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 199558293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haybittle J L. The use of the Gompertz function to relate changes in life expectancy to the standardized mortality ratio. Int J Epidemiol 199827885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai S P, Hardy R J, Wen C P. The standardized mortality ratio and life expectancy. Am J Epidemiol 1992135824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai D, Hardy R J, Tsai S P. Statistical analysis of the standardized mortality ratio and life expectancy. Am J Epidemiol 1996143832–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollard J H. Fun with Gompertz. Genus 1991471–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tison F, Letenneur L, Djossou F.et al Further evidence of increased risk of mortality of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 199660592–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger K, Breteler M M, Helmer C.et al Prognosis with Parkinson's disease in europe: A collaborative study of population‐based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology 200054S24–S27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgante L, Salemi G, Meneghini F.et al Parkinson disease survival: a population‐based study. Arch Neurol 200057507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herlofson K, Lie S A, Arsland D.et al Mortality and Parkinson disease: A community based study. Neurology 200462937–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Amelio M, Ragonese P, Morgante L.et al Long‐term survival of Parkinson's disease. A population‐based study. J Neurol 200625333–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoehn M M, Yahr M D. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 196717427–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nobrega F T, Glattre E, Kurland L T.et al Comments on the epidemiology of parkinsonism including prevalence and incidence statistics for Rochester, Minnesota, 1935−1966. In: Barbeau A, Brunette JS, eds. Progress in neurogenetics. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica, 1969474–485.

- 19.Sweet R D, McDowell F H. Five years' treatment of Parkinson's disease with levodopa. Therapeutic results and survival of 100 patients. Ann Intern Med 197583456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbeau A. Six years of high‐level levodopa therapy in severely akinetic parkinsonian patients. Arch Neurol 197633333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zumstein H, Siegfried J. Mortality among Parkinson patients treated with L‐dopa combined with a decarboxylase inhibitor. Eur Neurol 197614321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marttila R J, Rinne U K, Siirtola T.et al Mortality of patients with Parkinson's disease treated with levodopa. J Neurol 1977216147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joseph C, Chassan J B, Koch M L. Levodopa in Parkinson disease: a long‐term appraisal of mortality. Ann Neurol 19783116–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamond S G, Markham C H. Mortality of parkinson patients treated with Sinemet. In: Poirier LJ, Sourkes TL, Bedard PJ, eds. Advances in neurology. New York: Raven Press, 1979489–497.

- 25.Rinne U K, Sonninen V, Siirtola T.et al Long‐term responses of Parkinson's disease to levodopa therapy. J Neural Transm Suppl 1980149–156. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Curtis L, Lees A J, Stern G M.et al Effect of L‐dopa on course of Parkinson's disease. Lancet 19842211–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajput A H, Offord K P, Beard C M.et al Epidemiology of parkinsonism: incidence, classification, and mortality. Ann Neurol 198416278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cedarbaum J M, McDowell F H. Sixteen‐year follow‐up of 100 patients begun on levodopa in 1968: emerging problems. Adv Neurol 198745469–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diamond S G, Markham C H, Hoehn M M.et al Effect of age at onset on progression and mortality in Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1989391187–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebmeier K P, Calder S A, Crawford J R.et al Parkinson's disease in Aberdeen: survival after 3.5 years. Acta Neurol Scand 199081294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuroda K, Tatara K, Takatorige T.et al Effect of physical exercise on mortality in patients with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 19928655–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wermuth L, Stenager E N, Stenager E.et al Mortality in patients with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand 19959255–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett D A, Beckett L A, Murray A M.et al Prevalence of parkinsonian signs and associated mortality in a community population of older people. N Engl J Med 199633471–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morens D M, Davis J W, Grandinetti A.et al Epidemiologic observations on Parkinson's disease: incidence and mortality in a prospective study of middle‐aged men. Neurology 1996461044–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Louis E D, Marder K, Cote L.et al Mortality from Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 199754260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hely M A, Morris J G, Traficante R.et al The sydney multicentre study of Parkinson's disease: progression and mortality at 10 years. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 199967300–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Donnan P T, Steinke D T, Stubbings C.et al Selegiline and mortality in subjects with Parkinson's disease: a longitudinal community study. Neurology 2000551785–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guttman M, Slaughter P M, Theriault M E.et al Parkinsonism in Ontario: increased mortality compared with controls in a large cohort study. Neurology 2001572278–2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montastruc J L, Desboeuf K, Lapeyre‐Mestre M.et al Long‐term mortality results of the randomized controlled study comparing bromocriptine to which levodopa was later added with levodopa alone in previously untreated patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 200116511–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parashos S A, Maraganore D M, O'Brien P C.et al Medical services utilization and prognosis in Parkinson disease: a population‐based study. Mayo Clin Proc 200277918–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elbaz A, Bower J H, Peterson B J.et al Survival study of Parkinson disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Arch Neurol 20036091–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fall P A, Saleh A, Fredrickson M.et al Survival time, mortality, and cause of death in elderly patients with Parkinson's disease: a 9‐year follow‐up. Mov Disord 2003181312–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes T A, Ross H F, Mindham R H.et al Mortality in Parkinson's disease and its association with dementia and depression. Acta Neurol Scand 2004110118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Lau L M, Schipper C M, Hofman A.et al Prognosis of Parkinson disease: risk of dementia and mortality: the Rotterdam Study. Arch Neurol 2005621265–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H, Zhang S M, Schwarzschild M A.et al Survival of Parkinson's disease patients in a large prospective cohort of male health professionals. Mov Disord 2006211002–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gibb W R, Lees A J. A comparison of clinical and pathological features of young‐ and old‐onset Parkinson's disease. Neurology 1988381402–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jellinger K A, Seppi K, Wenning G K.et al Impact of coexistent Alzheimer pathology on the natural history of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm 2002109329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ 19963121215–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schrag A, Schott J M. Epidemiological, clinical, and genetic characteristics of early‐onset parkinsonism. Lancet Neurol 20065355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breteler M M, van den Ouweland F A, Grobbee D E.et al A community‐based study of dementia: the Rotterdam Elderly Study. Neuroepidemiology 199211(Suppl 1)23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riboli E. Nutrition and cancer: background and rationale of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Ann Oncol 19923783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maggi S, Zucchetto M, Grigoletto F.et al The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA): design and methods. Aging (Milano) 19946464–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ascherio A, Zhang S M, Hernan M A.et al Prospective study of caffeine consumption and risk of Parkinson's disease in men and women. Ann Neurol 20015056–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]