Abstract

Background and aims

A number of antibodies against microbial epitopes or self‐antigens have been associated with Crohn's disease. The development of antibodies reflects a loss of tolerance to intestinal bacteria that underlies Crohn's disease, resulting in an exaggerated adaptive immune response to these bacteria. It was hypothesised that the development of antimicrobial antibodies is influenced by the presence of genetic variants in pattern recognition receptor genes. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the influence of mutations in these innate immune receptor genes (nucleotide oligomerisation domain (NOD) 2/caspase recruitment domain (CARD) 15, NOD1/CARD4, TUCAN/CARDINAL/CARD8, Toll‐like receptor (TLR) 4, TLR2, TLR1 and TLR6) on the development of antimicrobial and antiglycan antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Materials and methods

A cohort of 1163 unrelated patients with IBD (874 Crohn's disease, 259 ulcerative colitis, 30 indeterminate colitis) and 312 controls were analysed for anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (gASCA) IgG, anti‐laminaribioside antibodies (ALCA) IgG, anti‐chitobioside antibodies (ACCA) IgA, anti‐mannobioside antibodies (AMCA) IgG and outer membrane porin (Omp) IgA and were genotyped for variants in NOD2/CARD15, TUCAN/CARDINAL/CARD8, NOD1/CARD4, TLR4, TLR1, TLR2 and TLR6.

Results

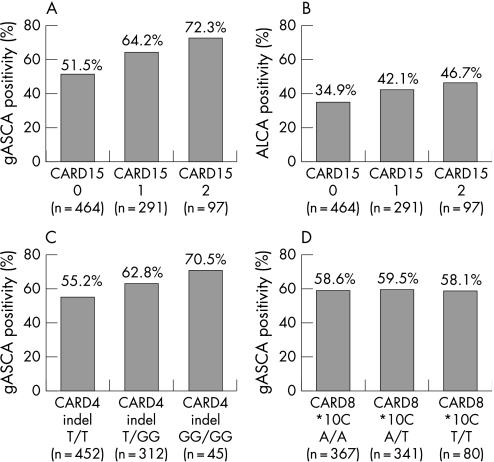

When compared with Crohn's disease patients without CARD15 mutations, the presence of at least one CARD15 variant in Crohn's disease patients more frequently led to gASCA positivity (66.1% versus 51.5%, p < 0.0001) and ALCA positivity (43.3% versus 34.9%, p = 0.018) and higher gASCA titers (85.7 versus 51.8 ELISA units, p < 0.0001), independent of ileal involvement. A gene dosage effect, with increasing gASCA and ALCA positivity for patients carrying none, one and two CARD15 variants, respectively, was seen for both markers. Similarly, Crohn's disease patients carrying NOD1/CARD4 indel had a higher prevalence of gASCA antibodies than wild‐type patients (63.8% versus 55.2%, p = 0.014), also with a gene dosage effect. An opposite effect was observed for the TLR4 D299G and TLR2 P631H variants, with a lower prevalence of ACCA antibodies (23.4% versus 35%, p = 0.013) and Omp antibodies (20.5% versus 34.6%, p = 0.009), respectively.

Conclusion

Variants in innate immune receptor genes were found to influence antibody formation against microbial epitopes. In this respect, it is intriguing that an opposite effect of CARD15 and TLR4 variants was observed. These findings may contribute to an understanding of the aetiology of the seroreactivity observed in IBD.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel diseases, CARD15, serology, intracellular signaling peptides and proteins, toll‐like receptors

The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are similar but distinct chronic diseases of the gut, characterized by diarrhoea and abdominal pain. The aetiology of IBD remains unknown, but a dysfunctional innate immune response against microbial factors in a genetically susceptible host seems important.

The caspase recruitment domain (CARD) 15 gene, coding for the nucleotide oligomerisation domain (NOD) 2 receptor, has been the first susceptibility gene identified for Crohn's disease.1,2 Three common variants this gene (R702W, G908R and L1007fsinsC) are present in 35–45%3,4,5,6,7,8,9 of European Crohn's disease patients, but explain only 20% of the genetic predisposition to Crohn's disease. NOD2/CARD15 is an intracytoplasmic receptor that binds bacterial peptidoglycan‐derived muramyl dipeptide through its leucin‐rich repeat (LRR) region.10,11 The Crohn's disease‐associated CARD15 mutations lead to defective recognition of muramyl dipeptide and a reduced clearance of intestinal bacteria. The NOD2 protein seems to be expressed in various cell types, including intestinal epithelial cells12 and Paneth cells,13 where it plays a role in regulation of the expression of bactericidal peptides,14,15 and where it can act as a direct antibacterial factor.12 Since the discovery of NOD2/CARD15, other genes coding for pattern recognition receptors of the innate immune system have been associated with IBD susceptibility or phenotypes: these include NOD1/CARD4,16 TUCAN/CARDINAL/CARD8,17 Toll‐like receptor (TLR) 4,18 TLR1, TLR2, TLR619 and TLR9.20

For many years, antibodies against microbial epitopes or against self‐antigens have been reported in patients with IBD.21 Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) have been studied most, and are found in 60–70% of patients with Crohn's disease.22,23,24,25 ASCA IgA or IgG antibodies are very specific for Crohn's disease and have mainly been associated with small bowel stricturing disease.26,27,28,29 They have also been reported in healthy relatives of Crohn's disease patients22,23,30 and in Crohn's disease patients before the onset of disease.31 Other antibodies identified in Crohn's disease include antibodies against the outer membrane porin (Omp) of bacteria,32 anti‐I2 (antibodies directed against Pseudomonas fluorescens),32 pancreatic auto‐antibodies,33 and anti‐CBir1 (anti‐flagellin antibodies34). Novel sugar antibodies directed against specific glycans localised at the surface of cells have recently been associated with Crohn's disease: anti‐chitobioside antibodies (ACCA) and anti‐laminaribioside antibodies (ALCA).35 The development of antibodies reflects a loss of tolerance to intestinal bacteria that underlies Crohn's disease, resulting in an elevated adaptive immune response to these bacteria. We hypothesised that this seroreactivity is dependent on the presence of genetic variants in genes of the innate immune system, and that the presence of more genetic variants would lead to increased seroreactivity. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the influence of mutations in innate immune receptors of importance for the gut (NOD2/CARD15, NOD1/CARD4, TUCAN/CARDINAL/CARD8, TLR4, TLR2, TLR1 and TLR6) on the development of antimicrobial and antiglycan antibodies in IBD.

Materials and methods

Patients and controls

Serum and DNA were obtained from 1163 unrelated patients with IBD (874 Crohn's disease, 259 ulcerative colitis, 30 indeterminate colitis) followed at the University Hospital Gasthuisberg, Leuven, a tertiary care referral centre. The control population consisted of 312 individuals, of whom 199 were unrelated healthy controls without familial history of IBD or known immune‐mediated disorders, and 113 were non‐IBD inflammatory controls including patients with diverticulitis, infectious colitis or ischaemic colitis; 99% of patients and controls were of western European/Caucasian origin. Ethical approval was given by the ethics board of the University of Leuven. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Samples and data were stored in a coded, anonymised database. Phenotypical information in Crohn's disease patients was recorded according to the Vienna classification for disease location and disease behaviour.36 All patients with upper gastrointestinal or anal involvement were classified in a non‐exclusive category, to avoid loss of information on their other involvement. Ulcerative colitis patients were classified using the Montreal classification37 according to the extent of the disease, as proctitis, left‐sided colitis or extensive colitis.

The clinical characteristics of the IBD patients are summarized in table 1. The control population (199 non‐inflammatory/113 inflammatory controls) consisted of 312 subjects (45% men), with a median age of 39 years (interquartile range 30–57).

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Crohn's disease patients (n = 874) | Ulcerative colitis patients (n = 259) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male n (%) | 362 (41%) | 136 (52%) |

| Median age at diagnosis (IQR) | 24 (18–31) | 26 (21–36) |

| Median follow‐up in years after diagnosis (IQR) | 15 (9–22) | 13 (9–19) |

| Disease location (n and %) (Vienna) | ||

| Ileal disease: L1 | 233/860 (27%) | – |

| Colonic disease: L2 | 153/860 (17%) | – |

| Ileocolonic disease: L3 | 471/860 (54%) | – |

| Upper gastrointestinal involvement | 95/860 (11%) | |

| Anal involvement | 314/855 (37%) | |

| Disease behaviour (n and %) (Vienna) | ||

| Inflammatory (B1) | 349/845 (41%) | – |

| Stricturing (B2) | 141/845 (16%) | – |

| Penetrating (B3) | 355/845 (40%) | – |

| Disease extent | ||

| Proctitis | – | 49/250 (19%) |

| Left‐sided colitis | – | 98/250 (38%) |

| Extensive colitis | – | 103/250 (40%) |

| Need for IBD surgery | 477/855 (55%) | 44/254 (17%) |

| History of smoking | 309/733 (42%) | 61/219 (23%) |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 117/435 (27%) | 16/90 (6%) |

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Serological analyses

All serum samples were analysed for gASCA IgG, ALCA IgG, ACCA IgA, AMCA IgG (Glycominds Ltd, Israel) and Omp IgA (Inova Diagnostics, San Diego, California, USA), using commercially available ELISA. Antibody levels and antibody positivity were determined according to the manufacturer's guidelines, and are expressed in ELISA units (EU). Antibody quartile sum scores were calculated for controls, Crohn's disease patients and ulcerative colitis patients, as previously described.32,38

DNA extraction and genotyping

DNA was extracted from whole venous blood by a salting‐out procedure39 and stored at −80°C. All subjects were genotyped for the main variants in CARD15 (R702W, G908R, L1007fsinsC), the stop codon mutation in CARD8 (*10C),17 three previously described polymorphisms in CARD4 (+27606, +32656, +45343),16 TLR4 D299G),18 and selected variants in TLR1 (R80T, S602I), TLR2 (R753G, P631H) and TLR6 (S249P).19 All studied genes are known to play a role in the recognition of bacterial products; polymorphisms were selected because of their previously described implication in IBD and only when they had a frequency of more than 1% for the rare allele in our cohort.1,16,17,18,19 Characterization of genotypes was performed by PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism.18,19 Genotyping for the CARD4 +32656 was performed using a custom‐made Taqman assay, manufactured and optimised by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, California, USA).

Statistics

Data were analysed using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and Statview 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) statistical software packages; linkage disequilibrium was calculated using Haploview software.40 A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Normality for continuous variables was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test, and in case of not normally distributed variables, a Mann–Whitney test was used to compare these variables between groups. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was verified for genotypes in all groups. Genotype and allele frequencies were compared using χ2 statistics. After univariate analysis for the different genotypes, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to correct for those factors that were found to be significant in univariate analysis.

We decided to focus our analyses on the comparison of groups of patients according to the presence or absence and the number of the genetic variants studied (not on the number of positive antibodies), because the hypothesised causal relationship between genetics and serological response, if present, would find its origin in the genetics.

Results

Distribution of genotypes and alleles in the studied subgroups

Genotype frequencies for the studied genes and polymorphisms are provided in supplementary table 1 (supplementary table 1 can be viewed on the Gut website at http://gut.bmj.com/supplemental).

All single nucleotide polymorphisms except for NOD1 +45343 were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in the control population. CARD15 variants were significantly more frequent in the Crohn's disease population (46%) when compared with ulcerative colitis patients (22%) and healthy controls (22%; both p < 0.0001). The frequency of the TLR4 299G variant was significantly higher in both Crohn's disease patients (9%) and ulcerative colitis patients (9%) when compared with healthy controls (5%; p = 0.007 and p = 0.02, respectively). For the other studied polymorphisms, the genotype and allele frequencies were similar for IBD patients (Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis) and healthy controls. The three studied NOD1 variants were in strong linkage disequilibrium in our population (D′ 0.89 for +27606 and +32656, 0.97 for +32656 and +45343 and 0.72 for +27606 and +45343).

Distribution of antibodies in the study subgroups

The distribution of the different antibodies in the study population is summarized in table 2. Cut‐off values for the different serological markers were defined according to receiver operating characteristic curves and according to manufacturer's recommendations.

Table 2 Distribution of the different serological markers in the studied subgroups.

| % gASCA + | % ALCA + | % AMCA + | % ACCA + | % Omp + | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBD patients | 529/1163 (45%) | 339/1163 (29%) | 503/1163 (43%) | 331/1163 (28%) | 311/1163 (27%) |

| Crohn's disease | 499/874 (57%) | 304/874 (35%) | 403/874 (46%) | 263/874 (30%) | 251/874 (29%) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 25/259 (10%) | 31/259 (12%) | 85/259 (33%) | 63/259 (24%) | 51/259 (20%) |

| Indeterminate colitis | 5/30 (17%) | 4/30 (13%) | 15/30 (50%) | 5/30 (17%) | 9/30 (30%) |

| Controls | 4/312 (1%) | 10/312 (3%) | 64/312 (20%) | 82/312 (26%) | 41/312 (13%) |

| Inflammatory controls | 2/113 (2%) | 1/113 (1%) | 30/113 (27%) | 39/113 (35%) | 28/113 (25%) |

| Non‐inflammatory controls | 2/199 (1%) | 9/199 (5%) | 34/199 (17%) | 43/199 (22%) | 13/199 (7%) |

ACCA, Anti‐chitobioside antibodies; ALCA, anti‐laminaribioside antibodies; AMCA, anti‐mannobioside antibodies; gASCA, anti‐S. cerevisiae antibodies; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; Omp, outer membrane porin.

NOD2/CARD15 and NOD1/CARD4 but not TUCAN/CARD8 variants increase serological response in Crohn's disease patients

Crohn's disease patients carrying at least one CARD15 variant were more frequently gASCA positive (66.1% versus 51.5%, p < 0.0001) and ALCA positive (43.3% versus 34.9%, p = 0.018) when compared with Crohn's disease patients without CARD15 mutations, and had a higher median gASCA titer (85.7 versus 51.8 EU, p < 0.0001). A gene dosage effect, with increasing gASCA and ALCA positivity for patients carrying no, one and two CARD15 variants, respectively, was seen for both markers (see fig 1A and B). No effect of CARD15 variants was observed on the prevalence of the other studied antibodies (data not shown).

Figure 1 Antibody positivity in Crohn's disease patients, according to their CARD15, CARD4 and CARD8 status. (A) Anti‐S. cerevisiae antibodies (gASCA) and caspase recruitment domain (CARD) 15, overall p value less than 0.0001. (B) anti‐laminaribioside antibodies (ALCA) and CARD15, overall p value 0.04. (C) gASCA and CARD4 indel, overall p value 0.03. (D) gASCA and CARD8, overall p value 0.3.

When adding up the number of positive antibodies (gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp), the mean number of positive antibodies increased from 1.84 ± 1.35 to 2.07 ± 1.36 and 2.36 ± 1.38 for Crohn's disease patients carrying no, one and two CARD15 variants, respectively (p = 0.001); the mean quartile sum score (calculated as previously described32,38) increased from 12.16 ± 3.44 to 12.85 ± 3.55 and 13.39 ± 3.48 for Crohn's disease patients carrying no, one and two CARD15 variants, respectively (p = 0.001).

Crohn's disease patients carrying at least one GG‐indel allele in NOD1/CARD4 had a higher prevalence of gASCA antibodies than patients carrying the wild‐type allele (63.8% versus 55.2%, p = 0.014). Here also, a gene dosage effect was observed for an increasing number of indel alleles (fig 1C). There was a trend towards higher gASCA titers in patients with at least one indel allele (73.3 versus 65.0 EU), but this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09). No effect was observed of the CARD4 indel variant on the prevalence of the other studied antibodies (data not shown).

CARD8 *10C (A > T) variants were not associated with a specific phenotype (data not shown) or with the presence of circulating antibodies in Crohn's disease patients (fig 1D).

TLR receptor variants modulate serological response in Crohn's disease patients

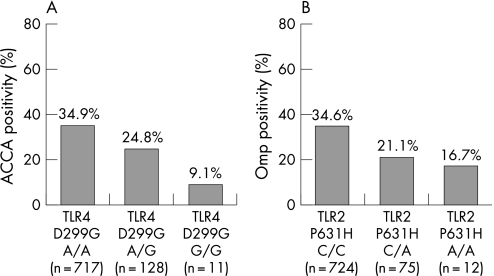

Crohn's disease patients with at least one mutation of TLR4 D299G (A > G) had a lower prevalence of ACCA antibodies when compared with wild‐type patients (23.4% versus 35%, p = 0.013), and a lower median ACCA titer (39 versus 49 EU, p = 0.05). A gene dosage effect was observed: ACCA antibody positivity in 34.9%, 24.8% and 9.1% of the patients for no, one and two variants, respectively (p = 0.026; fig 2A).

Figure 2 Antibody positivity in Crohn's disease patients, according to their TLR4 and TLR2 status. (A) Anti‐chitobioside antibodies (ACCA) and Toll‐like receptor (TLR) 4 D299G, overall p value less than 0.026. (B) Outer membrane porin (Omp) and TLR2 P631H, overall p value 0.035.

When adding up the number of positive antibodies (gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp), the mean number of positive antibodies decreased from 2.03 ± 1.39 to 1.67 ± 1.23 for Crohn's disease patients carrying no versus at least one TLR4 variant, respectively (p = 0.005); the mean quartile sum score decreased from 12.63 ± 3.58 to 11.90 ± 3.08 for Crohn's disease patients carrying no versus at least one TLR4 D299G variant, respectively (p = 0.024).

For the TLR2 P631H (C > A) variant, a decreasing prevalence of Omp antibodies was seen with an increasing number of variant alleles (34.6%, 21.1% and 16.7% for no, one and two A‐alleles respectively, p = 0.035; fig 2B). Patients carrying the variant A‐allele were less frequently Omp positive than the patients not carrying an A allele (20.5% versus 34.6%, p = 0.009), and had a lower median Omp titer (14.5 versus 16.7 EU, p = 0.012).

No effect was observed of the other TLR variants on the prevalence of the studied antibodies (data not shown).

Multivariate genotype–phenotype–serotype associations in Crohn's disease patients

As ASCA antibodies have been associated mainly with complicated small bowel disease,22,29,38,41 we tested whether the genotype–serotype associations found were independent of these phenotypes. In multivariate analysis, only gASCA positivity, ileal involvement and the absence of perianal disease were independently associated with CARD15 status (table 3). Similarly, only gASCA positivity and colonic involvement were independently associated with CARD4 indel variants.

Table 3 Multivariate analysis for CARD15 and CARD4 variants (logistic regression).

| gASCA positivity | Ileal involvement | Colonic involvement | Anal involvement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARD15 | 0.005 | 0.008 | NS | 0.029 |

| > 1 variant | OR 1.58 | OR 1.77 | OR 0.69 | |

| 95% CI 1.15 to 2.18 | 95% CI 1.16 to 2.70 | 95% CI 0.50 to 0.96 | ||

| CARD4 indel | 0.009 | NS | 0.007 | NS |

| > 1 variant | OR 1.48 | OR 1.57 | ||

| 95% CI 1.10 to 1.98 | 95% CI 1.13 to 2.18 |

CARD, Caspase recruitment domain; gASCA, anti‐S. cerevisiae antibodies. P value, OR and 95% CI are indicated.

The presence of at least one CARD15 variant (p = 0.0005, OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.28–2.41), ileal involvement (p = 0.021, OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.07–2.41), uncomplicated disease behaviour (p < 0.0001, OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.36–0.68) and smoking (p = 0.006, OR 0.645, 95% CI 0.47–0.88) were all independently associated with gASCA positivity.

For the TLR4 D299G variant, the only independent associations in multivariate analysis were the presence of anal disease, and an inverse association with the presence of ACCA antibodies and ileal involvement (table 4).

Table 4 Multivariate analysis for TLR4 variants (logistic regression).

| Anal involvement | Ileal involvement | ACCA positivity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR4 D299G | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.02 |

| > 1 variant | OR 1.54 | OR 0.56 | OR 0.58 |

| 95% CI 1.04 to 2.29 | 95% CI 0.36 to 0.89 | 95% CI 0.37 to 0.91 |

ACCA, Anti‐chitobioside antibodies; TLR, Toll‐like receptor. P value, OR and 95% CI are indicated.

NOD1/CARD4 and TLR4 variants influence serological response in ulcerative colitis patients

Ulcerative colitis patients carrying at least one CARD4 indel mutation were less frequently Omp positive (11% versus 28.8%, p = 0.004) when compared with patients wild type for the CARD4 indel allele, with a clear gene dosage effect (28.8%, 13% and 0% for no, one and two variant alleles respectively, p = 0.009). Also the two other studied NOD1/CARD4 variants were associated with a lower prevalence of Omp positivity (13.7% versus 27.4% for at least one +27606 variant, p = 0.26 and 10.8% versus 26.3% for at least one +45343 variant, p = 0.012). In multivariate analysis, both Omp positivity (p = 0.04, OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.21–0.96) and extensive colitis (p = 0.023, OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.27–0.90) were independently associated with the CARD4 +27606 variant.

Similarly, the TLR4 D299G variant was associated with a lower prevalence of Omp antibodies (5.3% versus 25.9%, p = 0.005), also with a gene dosage effect (26%, 5.7% and 0% for no, one, and two variant alleles, respectively, p = 0.02). Median Omp titers were lower in the group carrying at least one TLR4 variant (12.8 versus 16.6 EU, p = 0.009).

No effect was observed of the other genetic variants on the prevalence of the studied antibodies (data not shown) in ulcerative colitis patients.

Discussion

In this study, we found a significant association between variants in pattern recognition receptor genes and the development of antibodies against microbial epitopes, in a large and well‐characterized cohort of 874 Crohn's disease patients and 259 ulcerative colitis patients. Various antibodies directed against microbial epitopes or against endogenous antigens have previously been associated with IBD.21 The development of these antibodies reflects the loss of tolerance to intestinal bacteria that underlies IBD, resulting in an adaptive immune response to these bacteria. Antibodies against a mannan of S. cerevisiae (ASCA) have been studied most, and have been associated with the presence of Crohn's‐associated CARD15 mutations,41,42 although this could not be confirmed in all studies.26,43 Other genes that have been investigated for their association with antibody response include the tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) gene,44 in which an effect on ASCA development was found in CARD15‐negative patients, and the mannan‐binding lectin (MBL) gene,45 in which no association with ASCA antibodies was found.

First, we confirm the previously described association between NOD2/CARD15 variants and the presence of ASCA antibodies,41,42,46 independent of the associations with ileal involvement and complicated disease behaviour that have been described for CARD15 variants and ASCA antibodies, respectively. Moreover, patients carrying CARD15 variants had a higher number of positive serological antibodies, and a higher quartile sum score when compared with patients not carrying CARD15 variants, indicating increased and rather non‐specific seroreactivity. The three variants in the CARD15 gene we studied (R702W, G908R and L1007fsinsC) lead to defective recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide,14,47 reduced activation of nuclear factor kappa B,48 abnormal intestinal permeability49 and reduced expression of antimicrobial peptides such as defensins.14,15 All these factors may contribute to increased bacterial translocation and the subsequent development of antibodies to bacterial components. So far, it remains unclear whether the antibodies themselves play an additional role in the pathophysiology of Crohn's disease. The fact that we only observed an effect of NOD2/CARD15 mutations in patients with Crohn's disease (and not in ulcerative colitis patients or healthy controls) supports recent evidence that the presence of these mutations only modulates the impaired immune system in Crohn's disease patients.50

The studied NOD1/CARD4 variants were not associated with Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis in our population, but they also mediated serological response, both in Crohn's disease patients and in ulcerative colitis patients, although in the opposite way for both diseases. The cytosolic NOD1 receptor shares its structure with NOD2, and it activates nuclear factor kappa B after recognition of the diaminopimelic acid component of peptidoglycan, present in Gram‐negative bacilli and particular Gram‐positive bacteria.51 Similar to NOD2/CARD15 variants, variants in the NOD1/CARD4 gene were also associated with more frequent gASCA positivity in Crohn's disease patients (but without the all over seroreactivity seen with NOD2/CARD15 variants), and they were independently associated with colonic involvement. In ulcerative colitis patients, an inverse association between NOD1/CARD4 variants and both Omp positivity and extensive colitis was seen. These associations were independent of each other, so the antibody response in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients according to NOD1/CARD4 status cannot be explained solely by the extent of the disease in the colon, and other factors must contribute.

In contrast, TUCAN/CARDINAL/CARD8 variants were not associated with antibody response in IBD patients. This suggests that the LRR domain might be important for the modulation of seroreactivity as, unlike both CARD15 and CARD4, CARD8 does not have a LRR region for the recognition of microbial epitopes.52

Remarkably, for the TLRs, TLR4 and TLR2, an opposite effect on the development of antibodies was observed. For the TLR4 D299G variant, a lower prevalence of ACCA antibodies, lower total number of positive antibodies, and a lower mean quartile sum score were seen in Crohn's disease patients, and a lower prevalence of Omp antibodies in ulcerative colitis. For the TLR2 P631H variant, a lower prevalence of Omp antibodies was seen with an increasing number of variants. The TLR4 gene encodes the TLR4 receptor, a transmembrane receptor binding the lipopolysaccharide component of Gram‐negative bacteria through an extracellular domain consisting of an LRR region similar to that of CARD15 and CARD4. The intracellular domain of TLR4 resembles that of the IL‐1 receptor, as in all other TLRs. TLR4 is expressed in a variety of cell types, including intestinal epithelial cells, macrophages and dendritic cells of the gut.53 The D299G polymorphism within the LRR domain of TLR4 has been associated with hyporesponsiveness to lipopolysaccharide54 and several endogenous ligands,55 and an association with both Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis has been described;18 the molecular mechanisms of the reduced response to lipopolysaccharide are unknown. Our findings indicate that this polymorphism not only leads to lipopolysaccharide hyporesponsiveness, but to all over hyporesponsiveness to bacterial components and a subsequently reduced production of serological antibodies in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis patients. It is noteworthy that both Omp, to which serological response in ulcerative colitis patients with the TLR4 variant was decreased, and lipopolysaccharide, sensed by TLR4, are components of the outer membrane of Gram‐negative bacteria, which might indicate that in ulcerative colitis patients, a reduced response to Gram‐negative bacteria is more important than in Crohn's disease patients. In a recent study,42 no association was found between the TLR4 D299G variant and seroreactivity. It is possible that the antibody response to glycans is not influenced by the same genetic variants as the antibody response to I2 and CBir1 studied by Devlin et al.,42 and this may contribute to the apparently conflicting results.

Why mutations in the LRR containing CARDs and TLRs have an opposite effect on the development of antibody formation is unclear. It is possible that the difference in cellular position (at the cell surface for the TLRs and intracellular for the CARDs) is important and partly responsible for this difference. Another hypothesis is that interactions through the CARD or NOD domain play a role, or finally, that different downstream signalling pathways and feedback loops account for the difference.56

In conclusion, our findings suggest a main role for the LRR region in seroreactivity to microbial antibodies in Crohn's disease. We found significant associations between variants in genes for LRR‐containing innate immune receptors and antibodies against certain microbial epitopes. Interestingly, an opposite effect of CARD15 and TLR4 variants was observed with respect to the antibody response. This merits further exploration, and may contribute to our understanding of the seroreactivity in IBD patients and may help further to unravel the function of the IBD‐associated genetic polymorphisms and their influence on disease susceptibility.

Supplementary table 1 can be viewed on the Gut website at http://gut.bmj.com/supplemental.

Copyright © 2007 BMJ Publishing Group & British Society of Gastroenterology

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

L. Henckaerts and M. Pierik are doctoral fellows and S. Vermeire is a postdoctoral fellow of the Fund for Scientific Research (FWO), Brussels, Belgium.

The authors would like to thank Nir Dotan and Rom T. Altstock (Glycominds Ltd., Lod, Israel) and Gary Norman, Benjamin Schooler and Zakera Shums (Inova Diagnostics Inc., San Diego, California, USA) for supplying the ELISA antibody test kits for this study.

Abbreviations

ACCA - anti‐chitobioside antibodies

ALCA - anti‐laminaribioside antibodies

AMCA - anti‐mannobioside antibodies

ASCA - anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies

CARD - caspase recruitment domain

EU - ELISA units

IBD - inflammatory bowel disease

LRR - leucin‐rich repeat

NOD - nucleotide oligomerisation domain

Omp - outer membrane porin

TLR - Toll‐like receptor

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Supplementary table 1 can be viewed on the Gut website at http://gut.bmj.com/supplemental.

References

- 1.Hugot J P, Chamaillard M, Zouali H.et al Association of NOD2 leucine‐rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 2001411599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogura Y, Bonen D K, Inohara N.et al A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 2001411603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hampe J, Cuthbert A, Croucher P J P.et al Association between insertion mutation in NOD2 gene and Crohn's disease in German and British populations. Lancet 20013571925–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermeire S, Wild G, Kocher K.et al CARD15 genetic variation in a Quebec population: prevalence, genotype‐phenotype relationship, and haplotype structure. Am J Hum Genet 20027174–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croucher P J P, Mascheretti S, Hampe J.et al Haplotype structure and association to Crohn's disease of CARD15 mutations in two ethnically divergent populations. Eur J Hum Genet 2003116–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavanaugh J A, Adams K E, Quak E J.et al CARD15/NOD2 risk alleles in the development of Crohn's disease in the Australian population. Ann Hum Genet 20036735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roussomoustakaki M, Koutroubakis I, Vardas E M.et al NOD2 insertion mutation in a Cretan Crohn's disease population. Gastroenterology 2003124272–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendoza J L, Murillo L, Fernandez L.et al Prevalence of mutations of the NOD2/CARD15 gene and relation to phenotype in Spanish patients with Crohn disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003381235–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esters N, Pierik M, Van Steen K.et al Transmission of CARD15 (NOD2) variants within families of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 200499299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A.et al Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2. J Biol Chem 20032785509–5512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inohara N, Nunez G. The NOD: a signaling module that regulates apoptosis and host defense against pathogens. Oncogene 2001206473–6481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hisamatsu T, Suzuki M, Reinecker H C.et al CARD15/NOD2 functions as an antibacterial factor in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 2003124993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lala S, Ogura Y, Osborne C.et al Crohn's disease and the NOD2 gene: a role for paneth cells. Gastroenterology 200612547–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi K S, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y.et al Nod2‐dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science 2005307731–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wehkamp J, Harder J, Weichenthal M.et al NOD2 (CARD15) mutations in Crohn's disease are associated with diminished mucosal alpha‐defensin expression. Gut 2004531558–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGovern D P, Hysi P, Ahmad T.et al Association between a complex insertion/deletion polymorphism in NOD1 (CARD4) and susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease. Hum Mol Genet 2005141245–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGovern D P B, Butler H, Ahmad T.et al TUCAN (CARD8) genetic variants and inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 20061311190–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franchimont D, Vermeire S, El Housni H.et al Deficient host‐bacteria interactions in inflammatory bowel disease? The toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐4 Asp299gly polymorphism is associated with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Gut 200453987–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierik M, Joossens S, Van Steen K.et al Toll‐like receptor‐1,‐2, and‐6 polymorphisms influence disease extension in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torok H P, Glas J, Tonenchi L.et al Crohn's disease is associated with a toll‐like receptor‐9 polymorphism. Gastroenterology 2004127365–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bossuyt X. Serologic markers in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Chem 200652171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermeire S, Peeters M, Vlietinck R.et al Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA), phenotypes of IBD, and intestinal permeability: a study in IBD families. Inflamm Bowel Dis 200178–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sendid B, Quinton J F, Charrier G.et al Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies in familial Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1998931306–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peeters M, Joossens S, Vermeire S.et al Diagnostic value of anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 200196730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koutroubakis I E, Petinaki E, Mouzas I A.et al Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in Greek patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 200196449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnott I D R, Landers C J, Nimmo E J.et al Sero‐reactivity to microbial components in Crohn's disease is associated with disease severity and progression, but not NOD2/CARD15 genotype. Am J Gastroenterol 2004992376–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Annese V, Lombardi G, Perri F.et al Variants of CARD 15 are associated with an aggressive clinical course of Crohn's disease – an IG‐IBD study. Am J Gastroenterol 200510084–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helio T, Halme L, Lappalainen M.et al CARD15/NOD2 gene variants are associated with familially occurring and complicated forms of Crohn's disease. Gut 200352558–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vasiliauskas E A, Kam L Y, Karp L C.et al Marker antibody expression stratifies Crohn's disease into immunologically homogeneous subgroups with distinct clinical characteristics. Gut 200047487–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutton C L, Yang H, Li Z.et al Familial expression of anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies in affected and unaffected relatives of patients with Crohn's disease. Gut 20004658–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Israeli E, Grotto I, Gilburd B.et al Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies as predictors of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2005541232–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landers C J, Cohavy O, Misra R.et al Selected loss of tolerance evidenced by Crohn's disease‐associated immune responses to auto‐ and microbial antigens. Gastroenterology 2002123689–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joossens S, Vermeire S, Van Steen K.et al Pancreatic autoantibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 200410771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Targan S R, Landers C J, Yang H.et al Antibodies to CBir1 flagellin define a unique response that is associated independently with complicated Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 20051282020–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dotan I, Fishman S, Dgani Y.et al Antibodies against laminaribioside and chitobioside are novel serologic markers in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2006131366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J.et al A simple classification of Crohn's disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis 200068–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silverberg M S, Satsangi J, Ahmad T.et al Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 200519(Suppl A)5–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mow W S, Vasiliauskas E A, Lin Y C.et al Association of antibody responses to microbial antigens and complications of small bowel Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2004126414–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller S A, Dykes D D, Polesky H F. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucl Acids Res 1988161215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett J C, Fry B, Maller J.et al Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 200521263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vander Cruyssen B, Peeters H, Hoffman I E A.et al CARD15 polymorphisms are associated with anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies in caucasian Crohn's disease patients. Clin Exp Immunol 2005140354–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devlin S M, Yang H, Ippoliti A.et al NOD2 variants and antibody response to microbial antigens in Crohn's disease patients and their unaffected relatives. Gastroenterology 2007132576–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker L J, Aldhous M C, Drummond H E.et al Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) in Crohn's disease are associated with disease severity but not NOD2/CARD15 mutations. Clin Exp Immunol 2004135490–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castro‐Santos P, Mozo L, Gutierrez C.et al TNF[alpha] genotype influences development of IgA‐ASCA antibodies in Crohn's disease patients with CARD15 wild type. Clin Immunol 2006121305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joossens S B, Rector A, Vermeire S.et al Mannan‐binding lectin gene polymorphisms are not associated with anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2005128A443 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papp M, Altorjay I, Norman G L.et al Seroreactivity to microbial components in Crohn's disease is associated with ileal involvement, noninflammatory disease behavior and NOD2/CARD15 genotype, but not with risk for surgery in a Hungarian cohort of IBD patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 200713984–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnich N, Aguirre J E, Reinecker H C.et al Membrane recruitment of NOD2 in intestinal epithelial cells is essential for nuclear factor‐{kappa}B activation in muramyl dipeptide recognition. J Cell Biol 200617021–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Girardin S E, Boneca I G, Viala J.et al Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J Biol Chem 20032788869–8872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D'Inca R, Annese V, di Leo V.et al Increased intestinal permeability and NOD2 variants in familial and sporadic Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut 2006231455–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marks D J, Harbord M W, MacAllister R.et al Defective acute inflammation in Crohn's disease: a clinical investigation. Lancet 2006367668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chamaillard M, Hashimoto M, Horie Y.et al An essential role for NOD1 in host recognition of bacterial peptidoglycan containing diaminopimelic acid. Nature Immunol 20034702–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fritz J H, Ferrero R L, Philpott D J.et al Nod‐like proteins in immunity, inflammation and disease. Nat Immunol 200671250–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hausmann M, Kiessling S, Mestermann S.et al Toll‐like receptors 2 and 4 are up‐regulated during intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology 20021221987–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arbour N C, Lorenz E, Schutte B C.et al TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nat Genet 200625187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsan M F, Gao B. Endogenous ligands of Toll‐like receptors. J Leukoc Biol 200476514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strober W, Murray P J, Kitani A.et al Signalling pathways and molecular interactions of NOD1 and NOD2. Nat Rev Immunol 200669–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.