Abstract

Objective

To determine the effect of insulin for the management of hyperglycaemia in non‐diabetic patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.

Methods

An observational study from the MINAP (National Audit of Myocardial Infarction Project) database during 2003–5 in 201 hospitals in England and Wales. Patients were those with a final diagnosis of troponin‐positive acute coronary syndrome who were not previously known to have diabetes mellitus and whose blood glucose on admission was ⩾11 mmol/l. The main outcome measure was death at 7 and 30 days.

Results

Of 38 864 patients who were not previously known to be diabetic, 3835 (9.9%) had an admission glucose ⩾11 mmol/l. Of patients having a clear treatment strategy, 36% received diabetic treatment (31% with insulin). Mortality at 7 and 30 days was 11.6% and 15.8%, respectively, for those receiving insulin, and 16.5% and 22.1%, respectively, for those who did not. Compared with those who received insulin, after adjustment for age, gender, co‐morbidities and admission blood glucose concentration, patients who were not treated with insulin had a relative increased risk of death of 56% at 7 days and 51% at 30 days (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.0, p<0.001 at 7 days; HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.86, p<0.001 at 30 days).

Conclusion

In non‐diabetic patients with acute coronary syndrome and hyperglycaemia, treatment with insulin was associated with a reduction in the relative risk of death, evident within 7 days of admission, which persists at 30 days.

It is recognised that hyperglycaemia is a strong independent risk factor for patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes, and is a common finding in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction.1,2,3 Effective glycaemic control is recommended for patients with existing diabetes who have an acute coronary syndrome, although the additional benefit of a glucose/insulin infusion over other therapy has not been confirmed.4,5 However, appropriate management of non‐diabetic patients with hyperglycaemia remains uncertain, and the immediate benefit of insulin therapy is unproven.

We used observational data from the National Audit of Myocardial Infarction Project (MINAP) to examine the association of treatment with insulin with outcome in patients who were not previously known to be diabetic and who presented to hospital with an acute coronary syndrome and an admission blood glucose of ⩾11.0 mmol/l.

Methods

Details of MINAP have previously been published.6,7 The project uses a data set that allows examination of prehospital and in‐hospital care of acute coronary syndromes. The project is based on the technological platform developed by the Central Cardiac Audit Database group.8 The primary purpose of the project is to provide hospitals with contemporary online analyses of their individual performance and comparisons with national aggregate data against a limited number of audit standards. The data set includes a field for random blood glucose recorded on admission and two fields to record the type of treatment (insulin/oral/diet) used in hospital and on discharge. These fields were not part of the original data set, nor was their completion mandatory, and for this reason not all hospitals recorded these data. Two hundred and one of 229 hospitals in England and Wales recorded data on treatment of hyperglycaemia; median number 135 cases per hospital, interquartile range 59–247. Details of dosing schedules, types of insulin, duration of infusions of insulin and effects on glycaemic control are not recorded.

We analysed records of patients having a final diagnosis of troponin‐positive acute coronary syndrome (both ST elevation and non‐ST elevation infarctions) between January 2003 and March 2006 for whom an admission blood sugar was available. In order to prevent distortion of outcome analyses by multiple admissions, only the first admission during the study period was analysed.

We compared mortality at 7 and 30 days in the group treated with insulin (by any regime) with those who received no diabetic treatment in hospital and those in whom no treatment strategy was recorded. In the absence of follow‐up data to confirm adherence to a discharge regime, or the quality of glycaemic control, analyses of outcomes are based on an assumption that medication prescribed at discharge was continued after discharge. Vital status was obtained by linkage with the Office of National Statistics using the National Health Service (NHS) number unique to each patient.

Statistics

Percentages were used to compare categorical data, and differences in percentages were expressed with the 95% CI. Continuous data were expressed using medians with interquartile ranges. Relative risk of death is presented as a percentage of deaths for patients not receiving insulin divided by the percentage of deaths for those receiving insulin. Cox regression analysis was used to calculate the relative risk of death with 95% CI after adjustment for co‐morbidity and other confounding factors.

Results

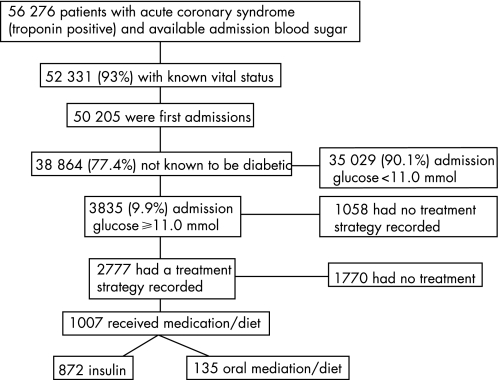

Between January 2003 and March 2006, 190 033 cases of troponin‐positive acute coronary syndrome were recorded in 201 collaborating hospitals; admission blood glucose was available in 56 276 (29.6%). There were no significant differences in age (median age 71.3 vs 71.7 years), gender (65.4% vs 64.7% males) or type of acute coronary syndrome (38.9% vs 38.8% ST elevation infarction) between those with and those without a record of blood glucose on admission. Of the 56 276, 52 331 (93%) had a valid NHS number with which to establish vital status. For 38 864 patients not previously diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, this was the first admission during the study period (fig 1). Of these, 3835 (9.9%) had an admission blood glucose ⩾11 mmol/l, and form the cohort for these analyses.

Figure 1 Patient cohort.

Patient characteristics and co‐morbidity

Patient admission characteristics are shown in table 1 and co‐morbidities at admission in table 2. Patients receiving insulin were younger, and were more likely to present with ST elevation. Admission blood sugar was higher for patients who received insulin compared with both those not given any treatment and those for whom no treatment strategy was known. Pulse and blood pressure at admission were similar. Patients treated with insulin tended to have lower rates of co‐morbidity. Patients for whom no treatment strategy was recorded had co‐morbidities intermediate between those treated with insulin and those receiving no treatment.

Table 1 Patient characteristics.

| Any insulin treatment in hospital n = 872 | No treatment n = 1770 | Treatment strategy not recorded n = 1058 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 72 | 60–80 | 76 | 66–83 | 73 | 62–82 |

| Male gender % | 60.2 | 524/871 | 55.6 | 982/1766 | 60 | 634/1056 |

| ST elevation infarction % | 58.4 | 509/872 | 42.8 | 758/1770 | 46.5 | 492/1058 |

| Length of stay, days. | 6.5 | 4.2–10.6 | 6.2 | 3.7–11.4 | 6.8 | 4.0–12.0 |

| Admission glucose, mmol/l* | 14.8 | 12.3–18.6 | 12.9 | 11.7–14.9 | 13.0 | 12.0–16.0 |

| Admission total cholesterol, mmol/l | 5.3 | 4.4–6.3 | 5.0 | 4.1–6.0 | 5.2 | 4.2–6.3 |

| Heart rate at admission, beats/min | 88 | 70–109 | 90 | 74–112 | 88 | 70–109 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 140 | 119–164 | 140 | 117–164 | 140 | 118–163 |

| Current smoking habit % | 33.1 | 275/832 | 25.2 | 401/1593 | 31 | 305/954 |

Unless stated in the table, data represent median values with interquartile ranges. Patients having oral medication or diet were excluded.

*Lower limit 11.0 mmol/l.

Table 2 Co‐morbidities at admission for patients having admission glucose ⩾11 mmol/l (n = 3700).

| Any insulin treatment in hospital n = 872 | No treatment n = 1770 | Treatment strategy not recorded n = 1058 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Previous angina | 24.8 | 213/858 | 32.1 | 561/1747 | 27.9 | 290/1038 |

| Previous AMI | 18.4 | 158/858 | 25.3 | 446/1761 | 24.5 | 255/1041 |

| Treated heart failure | 6.6 | 56/851 | 10.1 | 176/1747 | 9.1 | 93/1022 |

| Hypertension | 41.8 | 358/857 | 43.2 | 755/1746 | 45.7 | 471/1030 |

| Treated hyperlipidaemia | 19.5 | 161/825 | 20 | 341/1703 | 28.3 | 280/991 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 7.1 | 60/847 | 10.4 | 182/1747 | 9.2 | 94/1025 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3.6 | 31/851 | 4.3 | 76/1749 | 4.3 | 44/1023 |

| Chronic renal failure | 3.1 | 26/850 | 2.8 | 49/1752 | 3.4 | 35/1026 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 13.4 | 114/853 | 16.4 | 288/1751 | 17.4 | 152/874 |

Patients having oral medication or diet were excluded.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

Inpatient treatment

A treatment strategy provided was recorded for 2777/3835 (72%), of whom 1007 (36%) received some form of diabetic treatment and 1770 (64%) received none (fig 1). The majority of those receiving insulin were given the DIGAMI (Diabetes and Insulin‐Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction) insulin/glucose regime—607/872 (69.6%)—or an insulin pump—225/872 (25.8%).4 The remaining 40 (4.6%) insulin‐treated patients received single‐dose insulin regimes. In view of the relatively small numbers involved, patients given insulin by any regime were analysed jointly. Details of the oral diabetic medication used in hospital by 135 patients were not recorded, and further analysis of this group of patients was not performed.

Reperfusion treatment

Of those patients for whom a treatment strategy was recorded, 1267/2777 (45.6%) patients had a final diagnosis of ST elevation infarction. Those treated with insulin were more likely to receive some form of reperfusion treatment; 434/509 (85.3%) against 574/758 (75.7%) who received no diabetic treatment; difference 9.5%, 95% CI 5.2 to 13.9. Thrombolytic treatment was most commonly used, and primary angioplasty was used in only 25/1267 (2%) patients.

Treatment after discharge

Of 872 patients receiving insulin as an inpatient, 117 died in hospital and 128 were transferred to another hospital for further investigation. Another 12 had incomplete data on discharge treatment. For 615 who had received insulin in hospital for whom medication at discharge was specified, 254 (41.3%) were prescribed insulin and 146 (23.7%) oral diabetic medication, while 215 (35%) received no treatment.

Use of secondary prevention medication

For 1592 patients for whom details of secondary prevention medication were available, treatment use was analysed on the basis of failure to prescribe any one of the following: beta‐blockers, ACE inhibitors (or angiotensin receptor blockers), aspirin or other antiplatelet drug, or a statin. For patients given insulin in hospital, 388/596 (65.1%) were given all four drugs, while for patients not given insulin 610/996 (61.2%) were given all four drugs; difference 3.9%, 95% CI −1.0 to +12.0.

Outcome

The interval to death was available for 2629/2642 (99.5%) records for patients where an in‐hospital treatment strategy was recorded. The death rate at 7 and 30 days was 11.6% and 15.8%, respectively, in those receiving insulin, compared with 16.5% and 22.1%, respectively, in those not receiveing insulin (table 3) The crude mortality of the group for whom no treatment strategy was recorded was intermediate between those treated and those not treated, 128/1058, 12.1% at 7 days, and 195/1058, 18.4% at 30 days.

Table 3 Mortality, crude and adjusted relative risk of death at 7 and 30 days for all patients, and after exclusion of deaths occurring on the day of admission.

| All deaths | No treatment | Any insulin regime | Relative risk* | Adjusted relative risk | 95% CI | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| 7 days | 290/1761 | 16.5 | 101/868 | 11.6 | 1.42 | 1.56 | 1.22 to 2.0 | <0.001 |

| 30 days | 389/1761 | 22.1 | 137/868 | 15.8 | 1.40 | 1.51 | 1.22 to 1.86 | <0.001 |

| Deaths on day of admission excluded | ||||||||

| 1–7 days | 228/1682 | 13.6 | 80/841 | 9.5 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.09 to 1.89 | 0.011 |

| 1–30 days | 327/1682 | 19.4 | 116/841 | 13.8 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 1.11 to 1.78 | 0.004 |

*Relative risk; percentage dying in the untreated group divided by percentage dying in insulin‐treated group.

Cox regression analysis was used to compare the risk of death after adjustment for age (by age bands; 20–54, 55–64, 65–74, ⩾75 years), gender, pre‐existing heart failure, pre‐existing renal failure (creatinine >200 mmol), admission blood glucose, presence of ST elevation infarction, and history of previous angina or myocardial infarction. Compared with those who received insulin, patients who were not treated with insulin had an adjusted relative increased risk of death of 56% at 7 days and 51% at 30 days (hazard ratio (HR) 1.56, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.0, p<0.001 at 7 days; HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.86, p<0.001 at 30 days) (table 3).

In order to negate any bias resulting from deaths occurring prior to treatment or before any potential treatment effect of insulin had occurred, regression analyses were performed after excluding 79 deaths occurring on the day of admission (median interval 12 h). The adjusted relative risk of death was slightly reduced, but remained statistically significant (table 3).

The effect of insulin treatment on risk of death was examined separately for ST segment and non‐ST segment elevation infarction. The crude mortality was greater in both groups for patients who did not receive insulin, but the mortality difference between insulin‐treated patients and those without treatment was more marked for patients with ST segment elevation infarction (table 4). The adjusted relative risk of death was analysed separately for ST elevation and non‐ST segment elevation infarctions, using the covariates described. This was greater for untreated patients with ST elevation infarction than for those with non‐ST segment elevation infarction and was statistically significant. The adjusted relative risk for those with non‐ST segment elevation infarction who did not receive insulin was also greater, but this did not achieve statistical significance (table 4).

Table 4 Seven‐ and 30‐day mortality, relative risk and adjusted relative risk for patients with ST segment and non‐ST segment elevation infarction.

| No insulin treatment | Insulin treatment | Relative risk* | Adjusted relative risk | 95% CI | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||||

| ST elevation infarction | 7 days | 164/755 | 21.7 | 67/509 | 13.2 | 1.64 | 1.62 | 1.18 to 2.22 | 0.003 |

| 30 days | 193/755 | 25.6 | 80/509 | 15.7 | 1.63 | 1.58 | 1.19 to 2.10 | 0.002 | |

| Non‐ST elevation infarction | 7 days | 126/1006 | 12.5 | 34/359 | 9.5 | 1.32 | 1.30 | 0.86 to 1.96 | 0.211 |

| 30 days | 196/1006 | 19.5 | 57/359 | 15.9 | 1.23 | 1.25 | 0.90 to 1.74 | 0.188 | |

As patients with ST segment elevation infarction who received insulin were more likely to receive any reperfusion treatment, the use of reperfusion treatment was added to the covariates in an analysis limited to patients with ST elevation infarction. With this adjustment, the relative increased risk of death for untreated patients was 62% at 7 days and 58% at 30 days (HR 1.62, 95% CI 1.18 to 2.22, p = 0.003 at 7 days; and HR1.58, 95% CI 1.19 to 2.1, p = 0.002 at 30 days).

Discussion

Hyperglycaemia is very common in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes, and admission blood glucose is recognised as an independent predictor of mortality during short‐term follow‐up (28 days) after myocardial infarction after adjustment for glycated haemoglobin (HbAlc), age, gender and heart failure prior to the event.9 In a recent survey of European patients not known to be diabetic who presented with acute coronary syndromes, 36% had impaired glucose tolerance and 22% were classified as newly diagnosed diabetics after a glucose tolerance test.10 In the present study, almost 10% of patients without a previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus had an admission blood glucose ⩾11.0 mmol/l. It should be stressed that an admission blood sugar of 11 mmol/l is not diagnostic of diabetes in the context of an acute coronary event, and some may have normal glucose tolerance, although the majority will be diabetic or have impaired glucose tolerance.11,12

We found that after adjustment for age, gender, admission blood glucose and co‐morbidity, treatment with insulin was associated with a significantly lower relative risk of death by 7 and 30 days. This persisted after excluding deaths occurring on the day of admission. We did not collect information on left ventricular ejection fraction or Killip class, but there was no significant difference between groups with respect to either admission blood pressure or heart rate, and heart failure on admission is unlikely to be a confounder.

The majority of patients given insulin received infusions as described in the first DIGAMI study—consistent with recommendations current at the time.4 Although the second DIGAMI study did not confirm the benefits of insulin treatment, it recognised that control of blood glucose should be an integral part of the management of known type 2 diabetics with acute coronary events.5 As hyperglycaemic patients who were not known to be diabetic at enrolment were a minority (12.5%) in the first DIGAMI trial, the utility of insulin treatment in this group remains unproven by randomised trials. While we did not record blood glucose during treatment, we speculate that the differences in mortality outcome demonstrated in this study reflect an improvement in glycaemic control in those who received insulin. The difference was most marked in patients with ST elevation infarction, and although those with non‐ST elevation infarction had a reduction in crude mortality, and an adjusted relative risk suggesting treatment benefit, this did not achieve statistical significance.

A substantial number (28%) of hyperglycaemic patients had no treatment strategy recorded, which may reflect a lack of appreciation either of the significance of hyperglycaemia or of the possibility that the patient was an undiagnosed diabetic. These patients had characteristics, co‐morbidities and outcomes intermediate between those treated with insulin and those who were known not to have been offered treatment. We considered that an inability to allocate these patients was unlikely to be a source of bias.

This study has obvious limitations in relation to care provided after discharge, as we have details neither of compliance with treatment after discharge nor the degree of glycaemic control. For patients transferred to another hospital, the details of continuing treatment were also unavailable. Of those discharged from the admitting hospital, 41% continued insulin, about 24% were transferred to oral medication or diet, and for 35% diabetic medication was withdrawn. Withdrawal of treatment may have been based on formal assessment of glycometabolic state with an oral glucose tolerance test or simply on the basis of a return of normoglycaemia. While withdrawal of medication after discharge should have little impact on the 7‐day mortality presented here, as the median length of stay was 6.5 days, withdrawal of treatment after discharge or failure of compliance would tend to dilute any treatment effect for those in whom continuing treatment was appropriate. The adjusted relative risk of death at 30 days was very close to that at 7 days, indicating that there was, at least, no diminution of treatment effect between 7 and 30 days.

The small difference in use of secondary prevention medication in favour of the insulin‐treated group was statistically insignificant and, although data were incomplete, as details on use of secondary prevention medication were not available for some patients transferred to other hospitals, it is unlikely that this difference had any impact on 30‐day mortality.

Treatment offered to patients in the study was inconsistent. We found that the majority (64%) of hyperglycaemic patients were not given treatment to lower blood glucose. The upper quartile of untreated patients had an admission blood sugar ⩾14.9 mmol/l, suggesting that any clinical risk associated with hyperglycaemia, or the possibility that the patient had diabetes, was not recognised. Guidelines from national cardiology societies do not contain specific advice on treatment of hyperglycaemia, and some clinicians may retain a view that hyperglycaemia is simply an epiphenomenon—a marker of larger infarcts and poorer left ventricular function—resulting from catecholamine‐induced changes in glucose metabolism, rather than a reflection of insulin resistance.13 Although there is evidence from a randomised trial within the intensive care environment of the benefits of insulin treatment for hyperglycaemia, clinicians have not extrapolated this evidence to the care of acute coronary disease.14

There is now clear evidence that glucose itself may be toxic at higher plasma concentrations during acute coronary events. Laboratory and clinical investigations have identified a variety of mechanisms through which the adverse effects of glucose might be mediated. These include promotion of oxidative stress with impairment of endothelial function, promotion of thrombosis, inflammation and immunosuppresssion, and impairment of ischaemic preconditioning and the effectiveness of collateral blood supply into ischaemic zones.15,16,17,18 After multivariate analysis, hyperglycaemia (>11 mmol/l) is associated with increased in‐hospital mortality following primary angioplasty, whereas treated diabetes without admission hyperglycemia is not.19 Evidence of coronary microvascular dysfunction is supported by the higher frequency of the “no‐reflow phenomenon” following primary percutaneous coronary intervention in hyperglycaemic patients, an increase which is seen neither in treated diabetic patients with normoglycaemia nor in individuals with elevated HbAlc.20,21 The persistence of hyperglycaemia (blood glucose ⩾8.9 mmol/l from admission to at least 24 h after symptom onset) has been shown to be associated both with reduced myocardial perfusion despite patency of the infarct‐related artery and with predischarge left ventricular impairment.22 These findings suggest that both acute and persisting elevation of blood glucose, rather than an underlying “diabetic state”, promote an acute microvascular dysfunction that contributes to poorer short‐term outcome. These findings may also indicate why randomised trials of insulin treatment that included patients without major elevation of glucose or which failed to achieve a reduction in glucose level or a substantial difference in glucose level between the intervention and control groups failed to demonstrate any treatment benefit.5,23

The findings in this study are consistent with a meta‐analysis that compared the impact of admission glucose on outcome for hyperglycaemic non‐diabetic and treated diabetic patients.24 In that analysis, the adverse relationship between admission blood sugar and in‐hospital death was significantly worse for non‐diabetics that for treated diabetic patients, and we speculate that this difference reflects the greater degree of glycaemic control achieved in diabetic patients compared with non‐diabetics in whom little or no control of hyperglycaemia was achieved.

Conclusion—implications for clinical care

These observational data show for the first time that non‐diabetic patients presenting with hyperglycaemia in association with an acute coronary syndrome have a better short‐term prognosis when they are treated with insulin. These findings require confirmation with a randomised controlled trial. However, they support a pragmatic clinical approach of immediate treatment with insulin for patients presenting with a blood glucose ⩾11 mmol/l, followed by a formal assessment of glucose tolerance when practicable. We do not suggest that a level of 11 mmol/l is the optimum point for introduction of treatment, as others have shown a steadily increasing mortality in relation to increasing glucose levels throughout the range of blood sugars encountered.25 This suggests that a lower threshold for treatment may ultimately be considered appropriate.

Abbreviations

DIGAMI - Diabetes and Insulin‐Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction

HR - hazard ratio

Footnotes

Funding: The National Audit of Myocardial Infarction is funded by the Healthcare Commission.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Stranders I, Diamant M, van Gelder R E.et al Admission blood glucose level as risk indicator of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 2004164982–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norhammar A, Tenerz A, Nilsson G.et al Glucose metabolism in patients with acute myocardial infarction and no previous diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Lancet 20023592140–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norhammar A M, Ryden L, Malmberg K. Admission plasma glucose. Independent risk factor for long‐term prognosis after myocardial infarction even in non diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1999221827–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malmberg K, Norhammar A, Wedal H.et al Glycometabolic state at admission: important risk marker of mortality in conventionally treated patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction: long term results from the Diabetes and Insulin‐Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction (DIGAMI) trial. Circulation 1999992626–2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malmberg K, Ryden L, Wedel H.et al Intense metabolic control by means of insulin in patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI 2); effects on mortality and morbidity. Eur Heart J 200526650–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birkhead J S, Pearson M, Norris R M.et al The national audit of myocardial infarction: a new development in the audit process. J Clin Excellence 20024379–385. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkhead J S, Walker L, Pearson M.et al Improving care for patients with acute coronary syndromes: initial results from the national audit of myocardial infarction project (MINAP). Heart 2004901004–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rickards A, Cunningham D. From quantity to quality: the central cardiac audit database project. Heart 20008218–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadjadj S, Coisne D, Mauco G.et al Prognostic value of admission plasma glucose and HbA1c in acute myocardial infarction. Diabet Med 200422509–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartnik M, Lyden L, Ferrari R.et al The prevalence of abnormal glucose regulation in patients with coronary artery disease across Europe. The Euro Heart Survey on diabetes and the heart. Eur Heart J 2004251880–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishihara M, Inoue I, Kawagoe T.et al Is admission hyperglycaemia in non‐diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction a surrogate for previously undiagnosed glucose intolerance? Eur Heart J 2006272413–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tenerz A, Lonnberg I, Berne C.et al Myocardial infarction and prevalence of diabetes mellitus. Is increased casual blood glucose at admission a reliable criterion for the diagnosis of diabetes? Eur Heart J 2001221102–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oswald G A, Smith C C T, Betteridge D J.et al Determinants and importance of stress hyperglycaemia in non‐diabetic patients with myocardial infarction. BMJ 1986293917–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van den Berghe G, Woukers P, Weekers F.et al Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 20013451359–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaap A J, Shore A C, Tooke J E. Relationship of insulin resistance to microvascular dysfunction in subjects with fasting hyperglycaemia. Diabetologia 199740238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shechter M, Merz M B, Paul‐Labrador M J.et al Blood glucose and platelet dependent thrombosis in patients with coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 200035300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kersten J R, Toller W G, Gross E R.et al Diabetes abolishes ischemic preconditioning: role of glucose, insulin and osmolality. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2000278H1218–H1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kersten J R, Toller W G, Tessmer J P.et al Hyperglycemia reduces coronary collateral blood flow through a nitric oxide‐mediated mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001281H2097–H2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosuge M, Kimura K, Kojima S.et al Effects of glucose abnormalities on in‐hospital outcome after coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Circ J 200569375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwakura K, Ito H, Ikushima M.et al Association between hyperglycemia and the no‐reflow phenomenon in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am CoIl Cardiol 2003411–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishihara M, Kojima S, Sakamoto T.et al Acute hyperglycemia is associated with adverse outcome after acute myocardial infarction in the coronary intervention era. Am Heart J 2005150814–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosuge M, Komura K, Ishikawa T.et al Persistent hyperglycemia is associated with left ventricular dysfunction in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ J 20056923–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung N W, Wong V W, McLean M. The hyperglycemia: Intensive Insulin Infusion In Infarction (HI‐5) study. Diabetes Care 200629765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capes S, Hunt D, Malmberg K.et al Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet 2000355773–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosiborod M, Rathore S S, Inzucchi S E.et al Admission glucose and mortality in elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: implications for patients with and without recognized diabetes. Circulation 20051113078–3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]