Abstract

Previous research in the dorsal CA1 and dorsal CA3 subregions of the hippocampus has been shown to play an important role in mediating temporal order memory for spatial location information. What is not known is whether the dorsal CA3 and dorsal CA1 subregions of the hippocampus are also involved in temporal order for visual object information. Rats with dorsal CA1, dorsal CA3 or control lesions were tested in a temporal order task for visual objects using an exploratory paradigm. The results indicated that the controls and the dorsal CA3 lesioned rats preferred the first rather then the last object they had explored previously, indicating good memory for temporal order of object presentation. In contrast, rats with dorsal CA1 lesions displayed a profound deficit in remembering the order of the visual object presentations in that they preferred the last object rather than the first. All three groups of rats preferred a novel object compared to a previously explored object suggesting normal detection of visual object novelty. The results suggest that only the dorsal CA1, but not dorsal CA3, region is critical for processing temporal information for visual objects without affecting the detection of new visual objects.

Keywords: hippocampus, CA1, CA3, temporal order, object information

Introduction

The hippocampus has been shown to play an important role in processing of temporal information (Kesner, 1998; Levy, 1996; Lisman, 1999; Rolls and Kesner, 2006). More specifically the hippocampus supports processing of temporal order, recency discrimination or temporal pattern separation for spatial location and odor information in that a lesion of the hippocampus produces temporal order memory deficits (Chiba, Reynolds and Kesner, 1994; Fortin, Agster and Eichenbaum, 2002; Gilbert, Kesner and DeCoteau, 1998; Kesner, Gilbert and Barua, 2002). Similar results were obtained for temporal order memory for spatial locations in hypoxic subjects with hippocampal damage (Hopkins, Kesner and Goldstein, 1955a; Hopkins, Kesner and Goldstein, 1955b). It should be noted that patients with prefrontal lobe damage or rats with medial prefrontal cortex lesions also have difficulty in temporal order memory for spatial location information (for a review see Kesner, 1998). There are likely to be important interactions between the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. With respect to a subregional locus for processing temporal order for spatial locations, it has been reported that the dorsal CA1, but not dorsal dentate gyrus, is of critical importance in that dorsal CA1, but not dorsal dentate gyrus, lesions disrupt performance on a temporal order for spatial location information task (Gilbert, Kesner, and Lee, 2001). Based on unpublished data it appears that the dorsal CA3 also produces a deficit in processing temporal order for spatial information (Kesner and Gilbert, unpublished observations).

It would be of interest to extend the above mentioned finding to temporal order memory for visual object information. A modified paradigm was used based on previous research described by Mitchell and Lacona (1998) and Hanneson, Howland and Phillips (2004). They showed that rats when exposed to two or three different sets of objects select on a subsequent preference or recency discrimination test between the first or second and the third of the previously experienced objects the earlier of the two objects. As a control, normal rats when given a test between the first or the second and a novel object select the novel object. They show that rats with medial prefrontal or perirhinal cortex lesions disrupt recency discrimination or temporal order for visual objects without altering their preference for the novel object or recognition memory for the visual objects. The purpose of the present study was to use this new paradigm to examine temporal order memory for visual object information to examine whether both the dorsal CA1 and CA3 regions are critical for processing of temporal information for objects or whether the dorsal CA3 region only processes temporal information for space, but not for objects, in which case there would not be a deficit for dorsal CA3. Alternatively dorsal CA1 may mediate temporal processing for both spatial and nonspatial information and thus, there might be a deficit for visual object information

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Twenty-nine Long-Evans hooded rats, weighing 300–375 gm at the beginning of the study, were used as subjects. Food and water were available ad libitum throughout the experiment. Rats were maintained in standard plastic rodent cages throughout the experiment. All experimental procedures were performed during the light portion of the 12 hr light/dark cycle.

Surgery

Rats were handled 15 min daily for 1 week prior to surgery. They were then randomly divided into three separate groups that received dorsal CA1 (n=7), dorsal CA3 (n=9) or sham (n=13) lesions. Each animal was deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and then injected with atropine sulfate (0.2 mg/kg, i.p.). The animal was placed in a stereotaxic instrument (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA), and an incision was made along the midline of the scalp. The skull was exposed, and the instrument was adjusted to ensure a flat skull surface. Small burr holes were drilled through the skull and injections of neurotoxins were made through these holes for the following lesions: Dorsal CA1 lesion—3.6 mm posterior to bregma, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 mm lateral to midline, and 1.9 mm ventral from dura and dorsal CA3 lesion—(a) 2.5 mm posterior to bregma, 2.6 mm lateral to midline, and 3.2 mm ventral from dura, (b) 3.3 mm posterior to bregma, 3.3 mm lateral to midline, and 3.2 mm ventral from dura, and (c) 4.2 mm posterior to bregma, 4.2 mm lateral to midline, and 3.1 mm ventral from dura.

Axon-sparing, subregion-specific lesions of the dorsal CA1 and CA3 were made with ibotenic acid. For dCA1 lesions, ibotenic acid (6 mg/ml, 0.1 – 0.15 μl/site, 6.0 μl/hr) was slowly injected into the three sites per hemisphere. For dCA3 lesions, ibotenic acid (6 mg/ml, 0.1 – 0.2 μl/site, 6.0 μl/hr) was slowly injected into the three sites per hemisphere. Half of the control animals received CA1 vehicle injections and the other half received CA3 vehicle injections (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]). All injections were made with a 10- μl Hamilton (Reno, NV) syringe with a microinjection pump (Cole Parmer Instrument Company, Vernon Hill, IL).

Particular care was taken to prevent clogging of the injection needle by lowering the needle into the brain, raising the needle out from the brain, and running the injection pump to assure that the injection needle was not clogged with tissue. Once it was apparent that the needle was clear of any debris, it was again lowered to the specified coordinate, and the actual injection was made. Following surgery, the incisions were sutured and the rats were allowed to recover for one week before experimentation. They also received Children’s Tylenol in water as an analgesic. All protocols conformed to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Utah.

Apparatus

The test apparatus consisted of a rectangular red box with the following dimensions: 34 cm across × 92 cm length × 36 cm depth. The apparatus was kept in a well-lit room with no windows; one door, one chair, on small table. Multiple visual objects of various shapes, heights and colors were used in the temporal order for objects and object novelty detection tasks (see Figures 1 and 2)

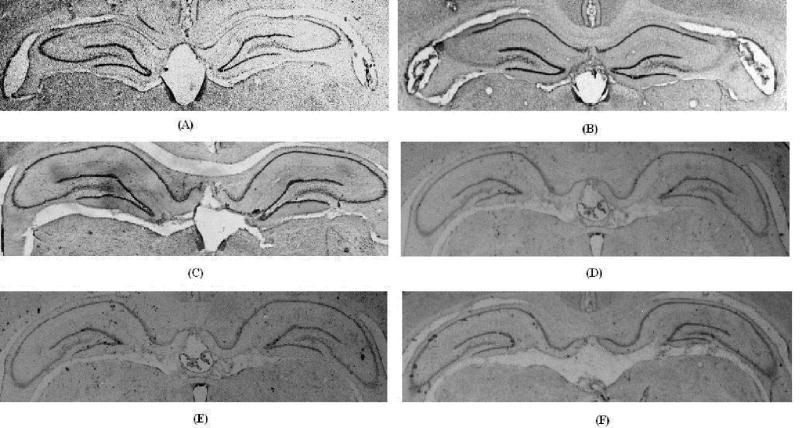

Figure 1.

Photographs of objects (A, B, and C) used in the temporal order task for objects.

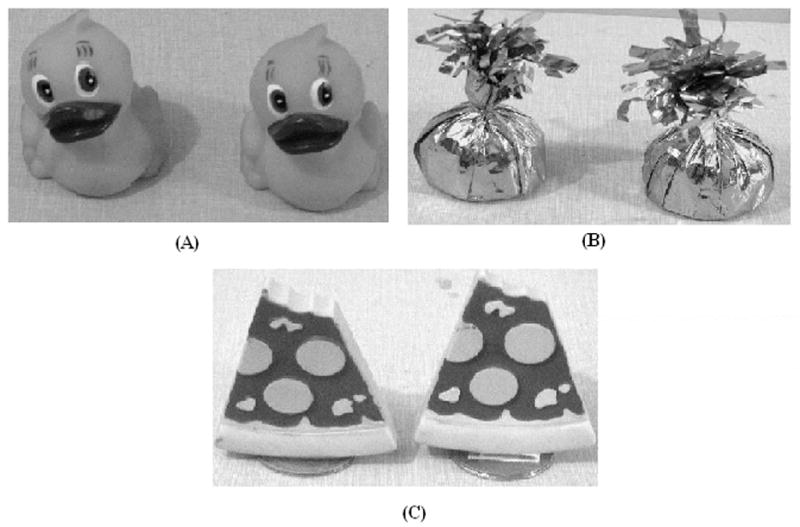

Figure 2.

Photographs of objects (A, B, C and D) used in the object novelty detection task.

Behavioral Testing

Rats were placed inside the box to explore each set of three objects (referred to as A-A, B-B, and C-C) for 5-minutes with a 3 minute inter-session interval. Objects were placed so that the distance was far apart so that there was no ambiguity as to which object the rat was exploring. After the third set of objects, the rats were given a three-minute time-out after which one of the two A objects and one of the two C objects were placed in opposite ends of the box. The rats were then returned to the box to measure preference for object A vs. object C for a 5 minute period. On a subsequent day with new objects, they were tested for detection of a novel object as a control using the same procedure previously described with the exception that one of the two A objects and one new object D are placed in opposite ends of the box to measure preference for object A vs. object D for a 5 minute period. All rats are tested once in the A-C preference test (temporal order) and on the A-D preference test (detection of object novelty) for a total of 2 days of testing. For each session, the rats were placed inside the box facing towards a wall at the apparatus’ midpoint in length. The dependent variable on all the tasks is exploration time with the objects. The criteria used for exploration time was measured in the number of seconds the rats spent touching and sniffing the objects. The experimenter was blind to the study.

For the temporal order test, the object sets consisted of a rubber ducky measuring 6.98 cm length × 8.25 cm height for object A, paper weight measuring 5.71 cm length × 12.7 cm height for object B, and rubber pizza slice measuring 8.89 cm length × 10.16 cm height for object C. For the detection of novel object test, the object set consisted of a cup with a straw measuring 5.08 cm diameter × 11.43 cm height for object A, a child’s party hat measuring 10.79 cm diameter × 14.60 cm height for object B, a character keychain measuring 7.62 cm length × 8.89 cm height for object C and a bird figurine measuring 6.98 cm diameter × 13.63 cm height for object D.

Histology

At the end of the experiments, each rat was given a lethal interperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital. The rat was perfused intracardially with 10% (wt/vol) Formalin in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. The brain was then removed and stored in 30% (vol/vol) sucrose-Formalin for 1 week. Transverse sections (24μm) were cut with a cryostat through the lesioned area and stained with cresyl violet. A program, ImageJ 1.31 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland), was used to quantify the extent of the lesion.

Results

Histology

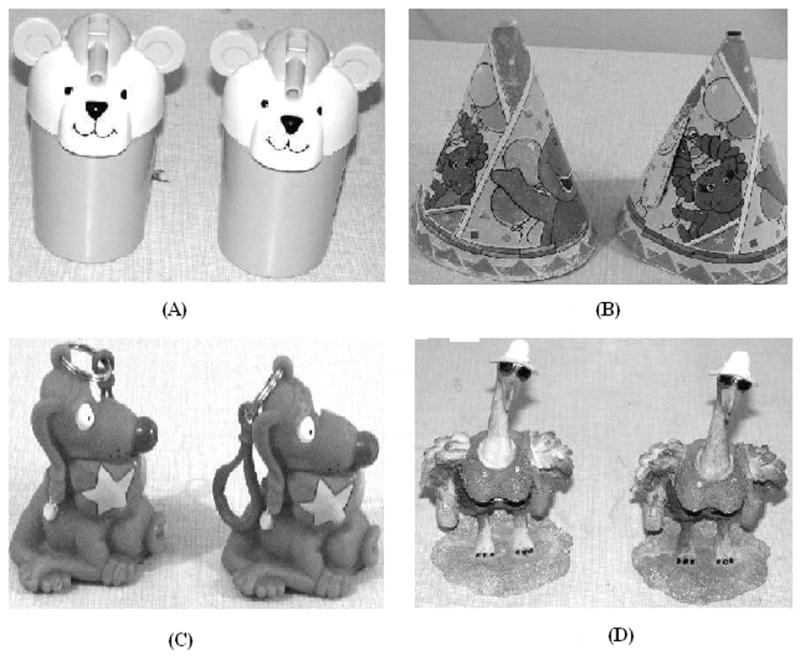

Since neither a CA1 nor CA3-unique neurotoxin is available, we have developed injection parameters suitable to induce subregion-specific lesions with ibotenic acid, which produce selective damage to either CA1 (Gilbert et al., 2001) or CA3 (Gilbert & Kesner, 2003; Jerman, Kesner, Lee, & Berman, 2005; Lee & Kesner, 2004) pyramidal cells. Although it is difficult to define the boundary between the dorsal and ventral portions of the hippocampus, the dorsal region was defined as the anterior 50% of the hippocampus (Moser & Moser, 1998). A quantitative analysis revealed that CA1 lesions resulted in 76 +/− 9.2% damage to the dorsal CA1 pyramidal cell layer with 9.1 +/− 8.8% damage to CA3 pyramids and 6.6 +/− 4.4% damage to DG granule cells, whereas CA3 lesions resulted in 85.4 +/− 2.3% damage to CA3 with 4.4 +/− .77% damage to CA1 and 1.2 +/− .72% damage to DG. As shown in Figure 3A, ibotenic acid injections into CA1 produced extensive degeneration of the pyramidal cells in CA1; Figure 3B shows the result of a representative CA3 lesion; Figure 3C shows a control animal that had received a saline injection. Figures 3 D, E, F show the results of more representative posterior hippocampus sections for the CA1, CA3 and control rats, respectively. There were no observable hippocampal lesions in these more posterior sections and furthermore there was no extra-hippocampal cortical damage in any of the animals.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs (10 X) of representative brain sections of A. CA1 ibotenic acid lesion, B. CA3 ibotenic acid lesion, and C. vehicle control, D. CA1 ibotenic acid lesion more posterior section, E. CA3 ibotenic acid lesion more posterior section, and F. vehicle control more posterior section. Notice no lesion damage in the more posterior sections.

Behavioral Analysis

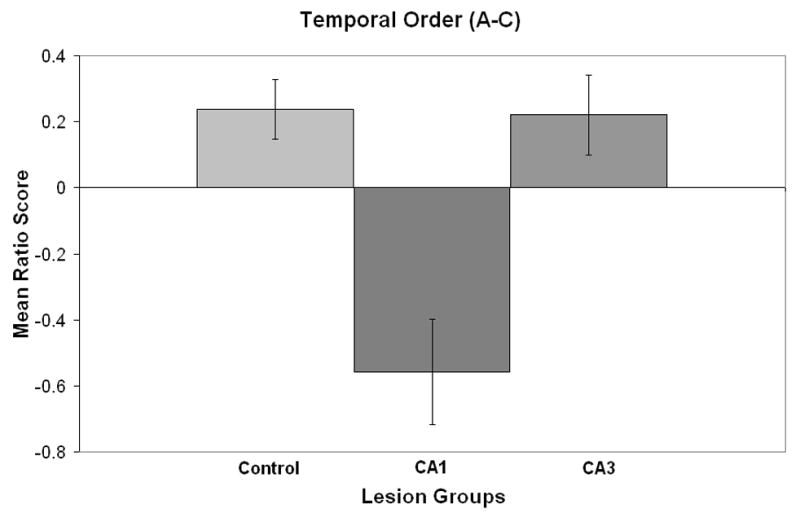

For the temporal order task the mean (± standard error) exploration of the objects A-A, objects B-B and objects C-C are shown in Table 1. A repeated measure ANOVA with groups as the between variable and objects as the within variable revealed that there was only a significant objects effect (F 4, 52 = 1.9, p<.0007), but there was no significant interaction between groups and objects (F 2, 52 = 8.4, p=.12). Thus, all groups showed a reduction of exploration across the three object exposures. The mean exploration (± standard error) of object A and object C are shown in Table 2. A repeated measure ANOVA with groups as the between variable and objects A vs C as the within variable revealed that there was only a significant group by objects effect (F 2, 26 = 1.9, p<.0011). The interaction is clearly due to the observation that there was an increased preference for A compared to C for the control and CA3 lesioned groups, but an increased preference for C compared to A for the CA1 lesioned group. In order to take into account the overall activity level of each rat for the temporal order task the following preference ratio of object A minus object C divided by object A plus object B was calculated. A zero score would reflect no preference for objects A or C. The effects of CA1, CA3 or control lesions are shown in Figure 4 and indicate that the CA1 lesioned rats preferred object C, whereas controls and CA3 lesioned rats preferred object A. A one-way ANOVA revealed that there was a significant difference among the groups (F 2, 25, = 13.5, p<.001). A subsequent Newman-Keuls test indicated that the CA1 lesioned group was significantly different from the control or CA3 lesioned groups (p<.01), whereas the control and CA3 lesioned groups did not differ from each other.

Table 1.

Mean (± standard error) exploration of Objects A-A, Objects B-B, and Objects C-C in the temporal odor task for Control, CA1 and CA3 lesioned groups.

| Objects A-A | Objects B-B | Objects C-C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE |

| Control | 35.8 | 6.2 | 26.9 | 3.8 | 20.5 | 3.3 |

| CA1 | 20.9 | 2.8 | 21.9 | 4.3 | 10.6 | 2.1 |

| CA3 | 24.1 | 5.1 | 24.8 | 5.7 | 21.5 | 6.6 |

Table 2.

Mean (± standard error) exploration of Object A and Object C in the temporal order task for Control, CA1 and CA3 lesioned groups.

| Object A | Object C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Mean | SE | Mean | SE |

| Control | 9.8 | 1.6 | 6.9 | 1.5 |

| CA1 | 2.6 | .6 | 12.0 | 3.9 |

| CA3 | 10.2 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 1.2 |

Figure 4.

Mean ratio score (± standard error) for the temporal order test for control, CA1, and CA3 lesions.

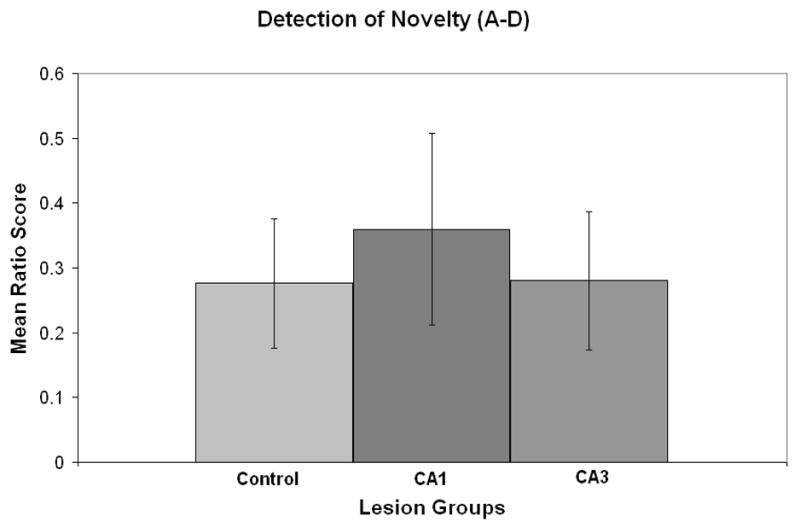

For the recognition or novelty detection task the mean (± standard error) exploration of the objects A-A, objects B-B and objects C-C are shown in Table 3. A repeated measure ANOVA with groups as the between variable and objects as the within variable revealed that there were no significant differences among the groups and objects. Thus, all groups continued to show exploration levels that did not differ across the three object exposures. The mean exploration (± standard error) of object A and object D are shown in Table 4. A repeated measure ANOVA with groups as the between variable and objects A vs. D as the within variable revealed that there was only a significant object preference effect (F 1, 26 = 8.9, p<.006). Thus, all groups showed a preference for the novel object. In order to take into account overall activity level of each rat for the novelty detection task the following preference ratio of object D minus object A divided by object D plus object A was calculated. A zero score would reflect no preference for objects A or D. The effects of CA1, CA3 or control lesions are shown in Figure 5 and indicate that all groups had a preference for object D, i.e. the novel object. A one-way ANOVA revealed that there were no significant differences among the groups (F 2, 25, = .10, p=.9).

Table 3.

Mean (± standard error) exploration of Objects A-A, Objects B-B, and Objects C-C in the novelty detection task for Control, CA1 and CA3 lesioned groups.

| Objects A-A | Objects B-B | Objects C-C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE |

| Control | 30.5 | 5.4 | 24.6 | 3.2 | 26.7 | 4.0 |

| CA1 | 21.6 | 4.3 | 21.7 | 3.3 | 31.6 | 7.8 |

| CA3 | 23.5 | 3.6 | 23.7 | 4.0 | 23.3 | 3.6 |

Table 4.

Mean (± standard error) exploration of Object A and Object D in the object novelty detection task for Control, CA1 and CA3 lesioned groups.

| Object A | Object D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Mean | SE | Mean | SE |

| Control | 11.3 | 2.1 | 20.3 | 3.5 |

| CA1 | 4.6 | .9 | 11.6 | 2.9 |

| CA3 | 8.9 | 2.8 | 15.5 | 6.1 |

Figure 5.

Mean ratio score (± standard error) for the novelty test for control, CA1, and CA3 lesions.

Discussion

The results indicate that for the temporal order task, control rats prefer object A in comparison with object C. In order to explain this preference for object A, it is assumed that rats prefer object A, because the rat has had more time for consolidation of object A in comparison with object C and thus has greater memory strength for object A. The results also indicate that rats with CA3 lesions have the same preference for object A as observed for control subjects. In contrast, results indicate that CA1 lesioned rats prefer object C in comparison with object A, suggesting an impairment for CA1 in temporal order memory for visual objects. A possible explanation for the observation that CA1 lesioned rats prefer object C rather than object A is based on the assumption that the trace of object A has not been consolidated properly and thus may be difficult to retrieve, but object C may still be processed by a short-term memory system mediated by CA3 and thus the rat prefers object C because of a short-term recency effect. This would also explain the lack of deficit observed following a lesion of CA3.

It is possible that a reduction in trace strength for object A would influence the preference test of object A vs. object D by enhancing the novelty effect. There does appear to be a somewhat greater novelty effect for CA1 compared to control and CA3, but this enhancement was not significant. Thus, neither CA1 nor CA3 lesions impair the ability to detect object novelty. These results support the idea that temporal processing of visual object information is a function of dorsal CA1 and parallels the findings of similar temporal order deficits for spatial information. The data also suggest that the dorsal CA3 only contributes to temporal order memory when spatial, but not visual object, information needs to be remembered. Furthermore, there appears to be a dissociation between the dorsal CA3 and dorsal CA1 in terms of subserving temporal order for visual objects, perhaps based on the idea that dorsal CA3 mediates short-term memory and dorsal CA1 mediates intermediate memory with the promotion of subsequent consolidation. In support of this idea, it has been shown that rats with CA3, but not CA1 lesions were impaired in the acquisition of a delayed non-match to place task (in an 8 arm maze) with a 10 sec delay. Also, when transferred to a new maze in a different room and using a 10 sec delay, there was a deficit for CA3, but not CA1, lesioned rats. Deficits for CA1 emerged when rats are transferred to a 5 min delay. Comparable deficits at a 5 min delay were also found for CA3 lesioned rats (Lee & Kesner, 2003). It should be noted that similar results as described for the lesion data were obtained following AP5 injections, which impaired transfer to the new environment when made into CA3 but not CA1. At 5 min delays AP5 injections into CA1 produced a sustained deficit in performance, whereas AP5 injections to CA3 did not produce a sustained deficit (Lee & Kesner, 2002).

One implication is that the CA3 contribution to this task can be implemented partly independently of CA1. Consistent with this, lesions of the fimbria impair the acquisition of the delayed match to place task at a 10 s delay (Hunsaker & Kesner, 2005). With longer delays, the task may no longer be implemented by CA3, but may involve LTP to set up an episodic-like memory which appears in this case to depend especially on CA1. Thus, this evidence suggests two types of short term memory implementations in the hippocampus. One is a very short term (10 s) memory (typically involving space) that may be implemented in CA3. The other is an intermediate term (5 min) memory that appears to be a more episodic-like memory involving LTP in CA1. Also, it is likely that the direct entorhinal to CA1 connections may be of importance in that the CA1 lesion effect on the delayed non-match to place task at 5 min delays can also be produced by injections of apomorphine into CA1 which influence the entorhinal to CA1 connections (Vago & Kesner, 2003).

Further evidence for some dissociation of an intermediate-term from a short-term memory in the hippocampus is that in the Hebb-Williams maze, learning/encoding measured within a day is impaired by CA3 and DG, but not by CA1 lesions. In contrast, retention/retrieval measured between days is impaired by CA1 but not by CA3 lesions. Thus, there may be an acquisition vs. retention dissociation with CA3 vs. CA1 lesions. Interestingly, the CA1 lesion effect on this task can also be produced by injections of apomorphine into CA1 which influence the entorhinal to CA1 connections, suggesting that on the following day when retrieval is at premium, the direct entorhinal to CA1 connections may play an important role (Vago & Kesner, 2005).

In addition to the processing of temporal information, the CA1 subregion appears to have cellular processes that match it to longer term types of memory than CA3. To test the idea that the CA1 region might be involved in retrieval after long (e.g. 5 min, 24 h) time delays, rats with CA1 lesions were tested in a modified Hebb-Williams maze. The results indicate that CA1 lesioned rats are impaired in retrieval with a 24 h delay (across-day tests), but have no difficulty in encoding new information (i.e. within-day tests) ((Vago & Kesner, 2005). Using a spatial contextual fear conditioning paradigm, rats with dorsal CA1 lesions are relative to controls impaired in retention (intermediate-term memory) of conditioning when tested 24 hours following acquisition (Lee & Kesner, 2004). In another study injections of propranolol into CA1 to block beta adrenergic receptors 5 min after contextual fear conditioning disrupted subsequent retention, whereas the same injections had no effect when administered 6 h later (Ji, Wang, & Li, 2003). In addition, it has been shown in a water maze study that post-training lesions of the CA1 24 hours after learning disrupted subsequent recall, whereas the same lesion made 3 weeks later did not produce a disruptive effect (Remondes & Schuman, 2004).

Thus, it appears that dorsal CA3 does not impair temporal order memory for visual objects based on the importance of recency (short-term memory) effects in determining the preference for object A vs. object C. Also, it appears that dorsal CA1 lesioned rats preferred object C rather than object A, because of difficulty in retrieving visual object information from intermediate –term memory and subsequent consolidation. Finally, the data indicating that there is a dissociation between dorsal CA3 and dorsal CA1 in temporal processing of visual object information support other observations suggesting that the dissociation between dorsal CA3 and dorsal CA1 is supported by a distinction between short-term and intermediate term memory.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NSF IBN-0135273 and NIH R01MH065314 awarded to R. P. K.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Chiba AA, Kesner RP, Reynolds AM. Memory for spatial location as a function of temporal lag in rats: role of hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1994;61:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin NJ, Agster KL, Eichenbaum HB. Critical role of the hippocampus in memory for sequences of events. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5:458–462. doi: 10.1038/nn834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP. Localization of function within the dorsal hippocampus: The role of the CA3 subregion in paired-associate learning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;117:1385–1394. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP, DeCoteau WE. Memory for spatial location: role of the hippocampus in mediating spatial pattern separation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:804–810. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00804.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP, Lee I. Dissociating hippocampal subregions: double dissociation between dentate gyrus and CA1. Hippocampus. 2001;11:626–636. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannesson DK, Howland GJ, Phillips AG. Interaction between perirhinal and medial prefrontal cortex is required for temporal order but not recognition memory for objects in rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;2(4):4596–4604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5517-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins RO, Kesner RP, Goldstein M. Item and order recognition memory in subjects with hypoxic brain injury. Brain and Cognition. 1995a;27:180–201. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1995.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins RO, Kesner RP, Goldstein M. Memory for novel and familiar temporal spatial and linguistic temporal distance information in hypoxic subjects. International Journal of Neuropsychology. 1995b;1:454–468. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerman TS, Kesner RP, Lee I, Berman RF. Patterns of hippocampal cell loss based on subregional lesions of the hippocampus. Brain Research. 2005;1065:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji JZ, Wang XM, Li BM. Deficit in long-term contextual fear memory induced by blockade of beta-adrenoceptors in hippocampal CA1 region. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;17:1947–1952. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP. Neural mediation of memory for time: role of hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex. Psychological Bulletin Reviews. 1998;5:585–596. [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Gilbert PE, Barua LA. The role of the hippocampus in memory for the temporal order of a sequence of odors. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;116:286–290. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Lee I, Gilbert PE. A behavioral assessment of hippocampal function based on a subregional analysis. Reviews in Neurosciences. 2004;15:333–351. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2004.15.5.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Gilbert PE. The role of CA3 in processing temporal order for spatial information (unpublished observations) [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Kesner RP. Differential contribution of NMDA receptors in hippocampal subregions to spatial working memory. Nature Neuroscience. 2002;5:162–168. doi: 10.1038/nn790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Kesner RP. Differential roles of dorsal hippocampal subregions in spatial working memory with short versus intermediate delay. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;117:1044–1053. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.5.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Kesner RP. Differential contributions of dorsal hippocampal subregions to memory acquisition and retrieval in contextual fear-conditioning. Hippocampus. 2004;14:301–310. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy WB. A sequence predicting CA3 is a flexible associator that learns and uses context to solve hippocampal-like tasks. Hippocampus. 1996;6:579–590. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:6<579::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE. Relating hippocampal circuitry to function: recall of memory sequences by reciprocal dentate-CA3 interactions. Neuron. 1999;22:233–242. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JB, Laiacona J. The medial frontal cortex and temporal memory: tests using spontaneous exploratory behaviour in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 1998;97:107–113. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser MB, Moser EI. Functional differentiation in the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1998;8:608–619. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:6<608::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remondes M, Schuman EM. Role for a cortical input to hippocampal area CA1 in the consolidation of a long-term memory. Nature. 2004;431:699–703. doi: 10.1038/nature02965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Kesner RP. A computational theory of hippocampal function, and empirical tests of the theory. Progress in Neurobiology. 2006;79:1–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vago D, Kesner RP. An electrophysiological and behavioral characterization of the temporoammonic pathway: Disruption produces deficits in retrieval and spatial mismatch. Society for Neuroscience 35th Annual Meeting; Washington, DC. 2005. [Google Scholar]