Abstract

The goal of the present experiments was to use a disconnection paradigm to test the interactions between the hippocampus and parietal cortex (PC) during an object-place paired associate learning task, dry-land water maze task, and a reaction-to-change task. Previous research indicates that these tasks are sensitive to hippocampal or PC disruption. Unilateral lesions were made to the dorsal hippocampus or posterior PC in contralateral hemispheres or ipsilateral hemispheres. It was hypothesized that if the hippocampus and PC interact, then contralateral lesioned animals should be markedly impaired compared to ipsilateral lesions. The results indicate that contralateral lesioned animals were significantly more impaired than animals with ipsilateral lesions during object-place paired-associate learning; however, both groups readily learned single discriminations (i.e., objects or places). Furthermore, contralateral lesioned animals traveled further to find the reward during acquisition of the dry-land water maze task and spent less time in the rewarded quadrant during the probe trial. Conversely, contralateral lesioned animals’ performance matched ipsilateral lesioned animals during the reaction-to-change paradigm. Thus, the hippocampus and PC interact during some tasks, presumably when tasks require multiple trials across days, but not during the detection of novelty within a single day.

INTRODUCTION

In the rat, the hippocampus and PC are not directly connected (Burwell, 2000; Lavenex and Amaral, 2000; Witter et al., 2000); however, data suggest that the hippocampus and PC could interact during spatial information processing. Recently, Save and colleagues (2005) found that bilateral PC lesions affected hippocampal place cell firing during a pellet-chasing task. In addition, bilateral lesions of the hippocampus result in impaired learning of many spatial navigation tasks. Lesions of the PC also result in similar deficits. For example, bilateral lesions of the hippocampus or PC disrupt learning of paired-associates (Long et al., 1998; Gilbert and Kesner, 2002), although it should be noted that a disruption only occurs when one component of the paired-associate is a spatial location. Primates, both human and nonhuman, as well as rats exhibit similar lesion-induced deficits (see Gilbert and Kesner, 2002). DiMattia and Kesner (1988) demonstrated that bilateral lesions of either the hippocampus or PC disrupt both acquisition and retention in the water maze. Kesner et al. (1992) demonstrated that bilateral lesions of the hippocampus or PC also disrupted both acquisition and retention of a cheese board spatial task (dry-land water maze task). Save and colleagues (1992a) reported that during a reaction-to-change task, bilateral lesions to either the hippocampus or PC result in decreased reaction to a spatial change, but intact exploration for a non-spatial change, such as changing of a visual cue. Using a multiple-object scene discrimination, DeCoteau and Kesner (1998) showed that bilateral lesions of the hippocampus or PC disrupted both space and space-object discriminations, whereas both lesions left object discriminations unimpaired. Finally, Rogers and Kesner (2006) found that post-training bilateral lesions of either the hippocampus or PC disrupted rats’ retention of two maze paradigms; although it should be noted that hippocampal lesions produced a slight, transient impairment, whereas PC lesioned animals were markedly more impaired. Based on the findings that bilateral lesions to either the hippocampus or PC result in similar behavioral impairments, it stands to reason that these two regions could interact during those behavioral tasks.

The hippocampus and PC connect through a variety of intermediate regions. Such regions include: retrosplenial cortex, subicular complex (comprised of the pre- and para-subiculum) and entorhinal cortex) (see Burwell, 2000). Bilateral lesions of any one of these regions also disrupt spatial information processing (Kesner and Giles 1998; Steffenach, Witter, Moser, and Moser,2005; van Groen, Kadish,and Wys, 2004). In the present study, the means by which interactions were tested was with the use of a disconnection paradigm. Using a disconnection experiment, one “can determine the extent to which a set of structures forms an integrated system with a common function” (Olton, 1983, pg. 348). In this procedure, unilateral lesions were made to both hippocampus and PC. In one group, lesions were made in ipsilateral hemispheres (i.e., left hippocampus, left PC or right hippocampus, right PC), whereas, in a second group lesions were made in contralateral hemispheres (i.e., left hippocampus, right PC or right hippocampus, left PC). An assumption made is that the right and left hemispheres operate in parallel. Ipsilateral lesions, therefore, should produce no deficit due to the intact function of the other hemisphere. By contrast, crossed lesions (i.e., unilateral lesions in contralateral hemispheres) should disrupt communication within each of the two hemispheres, thus disconnecting the two brain regions. Previously, a disconnection paradigm has shown the interaction of the hippocampus and EC (Parron, Poucet, & Save, 2006) and the hippocampus and anterior thalamic nuclei (Warburton et al., 2001). It was hypothesized that if the hippocampus and parietal cortex interact, then lesions placed in contralateral hemispheres should be impaired in the acquisition of an object-place paired associate task, acquisition of a spatial navigation task in a dry land version of the water maze, and detection of spatial and object novelty compared with lesions placed in ipsilateral hemispheres. It should be noted that the present work builds upon previous data (Long et al., 1998; Gilbert and Kesner, 2002; Kesner et al., 1992; Save et al., 1992a; Rogers and Kesner, unpublished observations); therefore, bilateral lesions were not included in the present experiments.

EXPERIMENT 1: OBJECT-PLACE PAIRED ASSOCIATE LEARNING

METHODS

Animals

Twelve male, Long-Evans rats (Simonsen Laboratories, Inc., Gilroy, CA, USA) approximately 4 months of age at the start of the experiment, weighing ~350 gm, served as subjects. The rats were housed individually in plastic tubs located in a colony with a 12-hr light-dark cycle. All rats had free access to water, with food restricted for the duration of testing to maintain each rat at approximately 85%–90% of its free-feeding weight. All testing was conducted during the light portion of the light-dark cycle.

Surgery

Surgical procedures were consistent across all experiments. Rats were randomly assigned to a surgery group. To determine whether the hippocampus and PC function in an interactive manner, animals received unilateral lesions of the hippocampus and the PC. For one group (n = 6), unilateral lesions were made in contralateral hemispheres, such as left hippocampus, right PC or right hippocampus, left PC (Contra). In another group (n = 6), lesions were made in the same hemisphere, such as left hippocampus, left PC or right hippocampus, right PC (Ipsi). If the two regions interact with each other, then the animals with contralateral lesions should be impaired relative to ipsilateral lesioned rats. Disconnection procedures were similar to those used by Warburton et al. (2001). Rats were anesthetized and maintained with a combination of isoflurane (2%) and medical air and given atropine sulfate (0.54 mg/kg i.m.) as a prophylactic. Each rat was placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments) with its head level. The scalp was incised and retracted to expose bregma and lambda in the same horizontal plane. Hippocampal lesions were made using ibotenic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, 6 mg/ml), infused using a micro infusion pump (Cole-Parmer; Vernon Hills, IL) and a 10 μL Hamilton syringe (Hamilton; Reno, NV) at a rate of 0.1μL/min and a volume of 0.2 μL per site into three sites within the dorsal hippocampus (2.8 mm posterior to bregma, 1.6 mm lateral to the midline, 3.0 mm ventral to dura; 3.3 mm posterior to bregma, 1.8 mm lateral to the midline, 2.8 mm ventral to dura; 4.1 mm posterior to bregma, 2.6 mm lateral to the midline, 2.8 mm ventral to dura). After infusion, the cannula remained in each site for two minutes to allow proper diffusion of the excitotoxin. Moser et al. (1993) reported spatial impairments after dorsal, but not ventral, hippocampal lesions; therefore, only dorsal lesions were made. Parietal cortex lesions were made via aspiration. The intended lesions extended from 1 mm to 4.5 mm posterior to bregma, 2 mm lateral to midline to approximately 1 mm above the rhinal sulcus in the medial-lateral plane, and 2 mm ventral to the dural surface. Following surgery, the incision was sutured and the rats were allowed to recover on a heating pad before returning to their home cage. In addition, rats received acetaminophen (children’s Tylenol; 200 mg/100 ml of water) as an analgesic and mashed food for three days following surgery.

Histology

After all behavioral testing was completed, rats were anaesthetized with a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/mL i.p.) and perfused intracardially with 0.9% phosphate buffered saline (pH 6.0) for 2 minutes followed by 10% buffered formalin (pH 7) for another 5 minutes. The brains were then extracted and stored in 30% sucrose formalin for three days, frozen, and sliced coronally into 40-μm sections with a freezing-stage microtome. All lesioned brains were cut along the coronal plane; every third section was stained with cresyl violet for verification of the lesions.

Apparatus

A round cheeseboard maze served as the test apparatus for this experiment. The surface of the apparatus stood 65 cm above the floor, was painted white, being 119 cm in diameter and 3.5 cm in thickness. One hundred seventy-seven food wells (2.5 cm in diameter and 1.5 cm deep) were drilled into the surface of the maze in evenly spaced parallel rows and columns 2 cm apart. A start box (24 cm long x 15 cm wide x 17 cm high) was placed on the maze surface, centered so that the door to the start box opened facing the center of the maze, with the posterior wall of the box placed along the edge of the maze. The box was equipped with a red Plexi-glass hinged top and a guillotine door that could be raised and lowered by the experimenter. The apparatus was kept in a well-lit room with no windows: one door, a chair, a small table, and posters hanging on the walls served as spatial cues.

Training

During the first week of training, each animal explored the test apparatus for 0.25 h. During the exploration period, ten pieces of Froot Loop cereal (Kellogg’s brand) were randomly spread across the surface of the apparatus. The guillotine door to the start box remained open to allow each animal access to the interior of the box. Beginning the second week of training, a single, neutral object was introduced in the testing apparatus. An object was used so that each animal could familiarize itself with displacing objects to receive a food reward. The object was a 2-cm wide X 5-cm tall wood block that was painted gray. The object was placed in the center-most food well of the maze. On each shaping trial, a piece of cereal was placed in front of the object on the maze surface. The animal was placed into the start box with the door closed. Once the door was opened, the animal was allowed to exit the box, retrieve the cereal, and return to the start box. The animal was allowed 45 sec to consume the cereal while the experimenter replaced the cereal reward. This procedure was followed for twelve days. Once the animal retrieved the food reward consistently, the food reward was placed in the food well previously covered by the object and the object was placed on the side of the food well opposite the start box and the animal. On each ensuing trial, the object was positioned to cover a larger portion of the food well until the base of the object covered the baited food well completely. Once an animal consistently displaced the object to receive a food reward, the animal began the testing phase of the object-place paired associate learning task.

Testing

Two paired-associates were reinforced which consisted of one particular object (A) in one particular location (1) and a different object (B) in a different location (2). Mispairs that were not reinforced included object (A) in location (2) and object (B) in location (1). The two locations were equidistant from the centermost food-well and were located along a row of food-wells perpendicular to the start box, 67.5 cm from the posterior of the start box. Each object consisted of a small toy (approx. 6–8 cm tall) glued to a flat metal washer (5 cm in diameter). Rats learned that if an object was presented in its paired location then the rat should displace the object to receive a reward (Go), whereas, when an object was presented in its mispaired location, then the rat should withhold displacing the object (No-Go). The rats started each trial in the start box and the latency between the opening of the door and the time until the animal displaced the object was recorded and used as the dependent measure. If the rat did not displace the object within 10 s, a latency of 10 s was recorded and the rat was returned to the start box. Difference scores calculated from the latencies between go/no-go stimuli assessed learning; increased latencies indicated better learning (since animals learn not to run during non-rewarded trials, hence “no-go”). Six paired-associates and six mispairs were presented each day until each rat completed 360 trials. Controls rats learn this task easily within the 360 trials (Gilbert and Kesner, 2002).

When testing was complete, animals began single discrimination training. Successive discrimination go/no-go tasks for spatial location and visual objects serve to rule out the possibility that any deficit in learning the object-place paired associate task is due to an inability to inhibit a response or to visually discriminate between two visual objects. On the first task, two of the same neutral objects (i.e. wood blocks) were used as stimuli and the same two locations used on the paired-associate task were used as the locations to be discriminated. One location was designated as the positive/rewarded location and the second location was designated as the negative/nonrewarded location. The rewarded location, in which a Froot Loop was located under the neutral object, was randomized across rats. Each rat was tested in the same manner as described for the paired-associate task. Rats received 12 trials per day and were trained until their performance reached a criterion of ten correct responses on ten consecutive trials. Latencies lower than 2 s on a positive trial or higher than 7 s on a negative trial were scored as correct responses. On the second task, two toy objects similar to those used in the paired associate task were used as stimuli and the same two locations used on the paired-associate task were used as the locations. One object was designated as the positive/rewarded object and the second object was designated as the negative/nonrewarded object. The rewarded object, under which a Froot Loop was located, was randomized across rats. Each rat was tested in the same manner as described for the paired-associate task. Rats received 12 trials per day and were trained until their performance reached a criterion of ten correct responses on ten consecutive trials. Latencies lower than 2 s on a positive trial or higher than 7 s on a negative trial were scored as correct responses. Training and testing procedures match those used by Gilbert and Kesner (2002).

Data Analysis

Subtracting the mean latency of the mispaired trials from the mean latency of the paired trials was used to assess paired-associate learning. The average of the daily scores was calculated for each five day block, resulting in one score per five days for a total of six scores. Data were analyzed with a mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) including a between-subject Group factor and repeated measures Trials factor and post-hoc analyses when necessary, using a Student-Newman-Keuls test. Simple discrimination tasks, measured via trials-to-criteria, were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA.

RESULTS

Histology

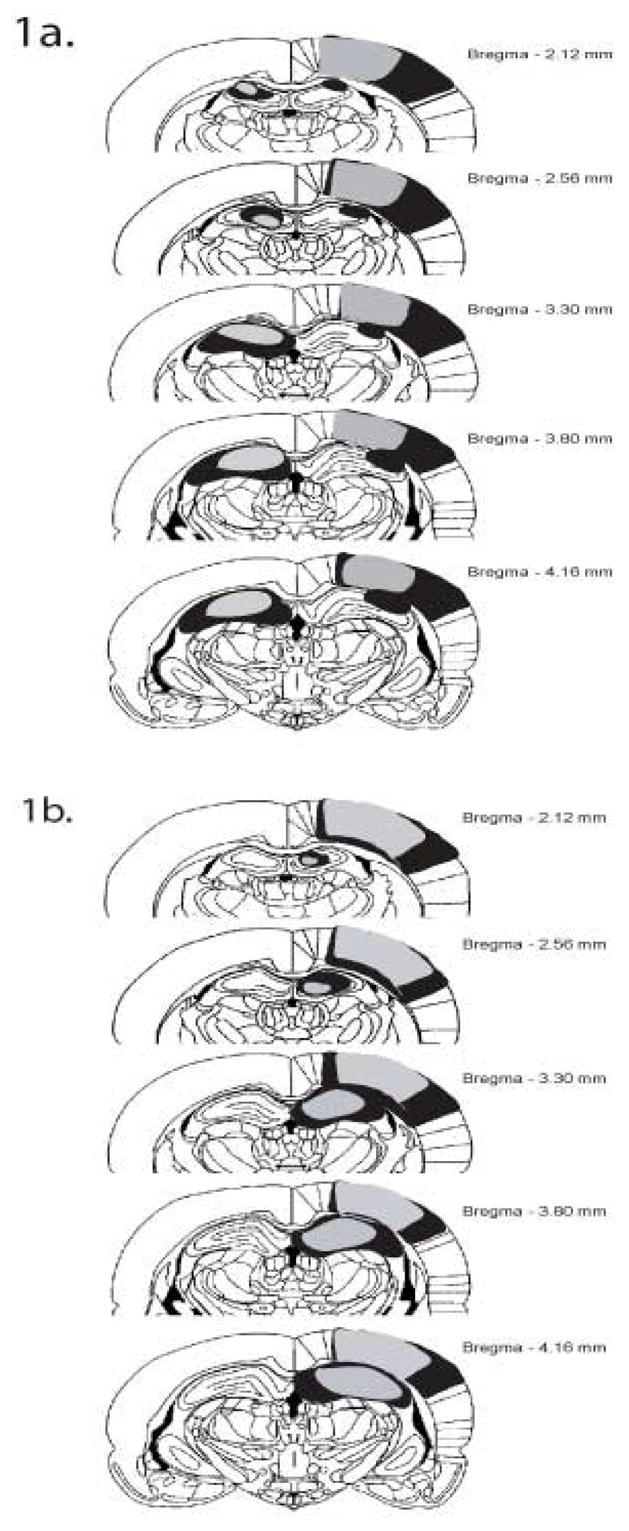

Figure 1a shows a schematic representation of the largest (black) and smallest (gray) contralateral lesions for Experiments 1 and 2. Some of the contralateral lesion animals (n = 7) had lesions of the right PC and left hippocampus; others (n = 5) had lesions of the left PC and right hippocampus. There were no observed differences between these two groups. In both cases, the PC lesions were complete and consistent across subjects. The dorsal hippocampal lesions also tended to be complete; however, in one subject the damage extended bilaterally into the CA1 region of the dorsal hippocampus. This damage was minute and the animal was still included in the data analysis. Figure 1b shows a schematic representation of the largest (black) and smallest (gray) ipsilateral lesion. Some of the ipsilateral lesioned animals (n = 6) had lesions of the right side; others (n = 6) had lesions of the left side. In both cases, the PC lesions were complete and consistent across subjects. The dorsal hippocampal lesions also tended to be complete.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the largest (black) and smallest (gray) ipsilateral (A) and contralateral lesion (B).

Contralateral lesions of the hippocampus and PC impair object-place paired associate learning

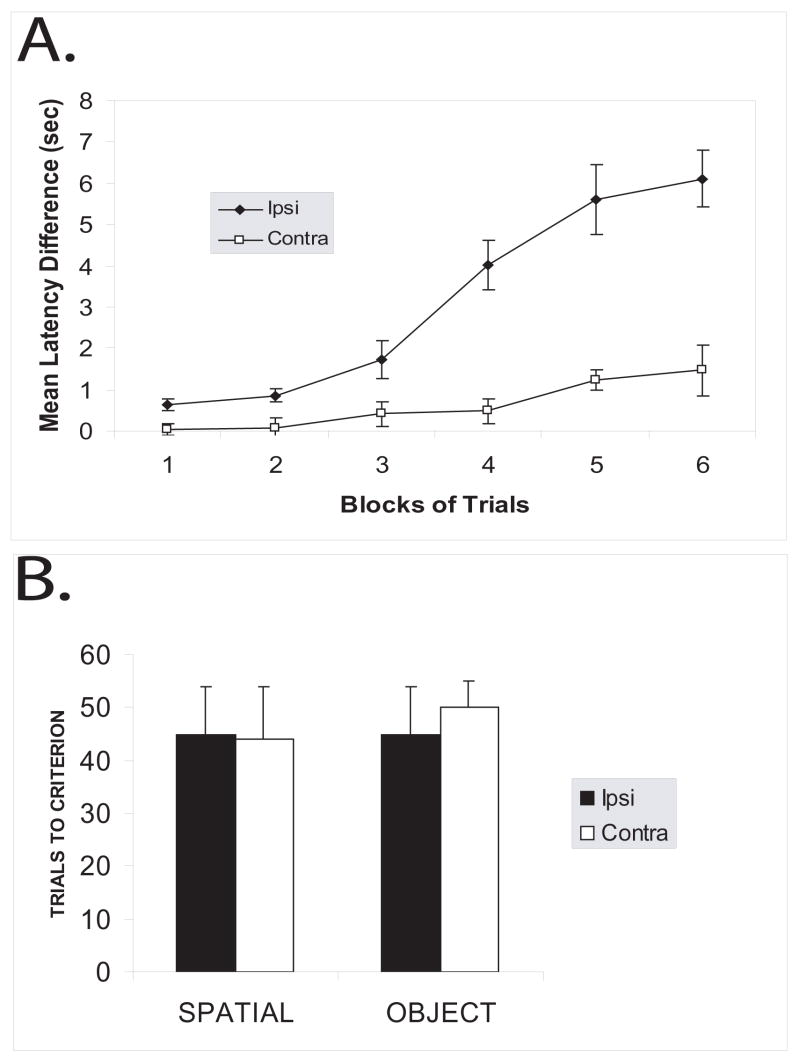

When unilateral lesions were placed in contralateral hemispheres within the dorsal hippocampus and PC, an overall deficit in object-place paired associate learning was observed when compared to unilateral lesions placed in ipsilateral hemispheres (Figure 2a). A repeated-measures ANOVA was performed on the data with groups as the between-subjects variable and blocks of trials (weeks) as the within-subjects variable. There was a significant main effect for groups [F (1, 10) = 33.74; p<0.001] as well as days [F (5, 50) = 32.16; p<0.001]. In addition, there was a significant interaction between groups and days [F (5, 50) = 12.70; p<0.001]. Post hoc analysis (Student-Newman-Keuls) performed on the interaction between groups and days revealed that the contralateral lesioned animals had a significantly smaller latency difference score than the ipsilateral lesioned animals during Blocks 4, 5, and 6, suggesting an inability to learn the object-place paired associate task.

Figure 2.

A: Object-place paired associate learning. Results, shown as means +/− SEM, indicate that contralateral lesioned animals (Contra) have significantly lower latencies, indicating a failure to learn the task. B: Simple discrimination tasks. Results, shown as means +/− SEM, indicate that both groups readily learned both ‘spatial’ and ‘object’ simple discrimination tasks.

Contralateral lesions of the hippocampus and PC have no effect on simple discrimination tasks

Figure 2b shows the performance of the contralateral and ipsilateral lesioned animals on the spatial and object discrimination tasks. Rats were trained on this task until their performance reached a criterion of ten correct responses on ten consecutive trials. The data reveal no significant differences in performance between the contralateral and ipsilateral lesioned animals on the two discrimination tasks. Two separate one-way ANOVA tests indicate that the number of trials required by the contralateral lesioned animals was not significantly different from the number of trials required by the ipsilateral lesioned animals on the spatial, [F (1,10) = 0.14; p>0.05]; or object, [F (1,10) = 0.69; p>0.05], discrimination tasks. Therefore, the data suggest that the contralateral lesioned animals were able to discriminate between the particular spatial locations and objects used in the paired-associate task as well as the ipsilateral lesioned animals. Furthermore, because the discrimination tasks were successive go/no-go tasks and the contralateral lesioned animals learned the discriminations, the data also suggest that the deficits observed in the contralateral lesioned animals were not due to a deficit in response inhibition. Thus, the deficit seen in the contralateral lesioned animals on the object-place paired associate learning task was not due to an inability to discriminate between spatial locations, objects, or a deficit in response inhibition.

EXPERIMENT 2: DRY-LAND WATER MAZE TASK

METHODS

Animals

Twelve new male, Long-Evans rats (Simonsen Laboratories, Inc., Gilroy, CA, USA) approximately 4 months of age at the start of the experiment, weighing ~350 gm, served as subjects. Half of the rats had contralateral lesions, whereas, the other half received ipsilateral lesions. The rats were housed individually in plastic tubs located in a colony with a 12-hr light-dark cycle. All rats had free access to water, with food restricted for the duration of testing to maintain each rat at approximately 85%–90% of its free-feeding weight. All testing was conducted during the light portion of the light-dark cycle.

Apparatus

The same round cheeseboard maze that was used in Experiment 1 served as the test apparatus.

Testing

For the first 3 d, each rat was allowed to explore the cheese board with food available in every hole. Starting on the fourth day, each rat was randomly assigned a food location in one of four quadrants. The rats were given 8 training trials per day for two consecutive days, two from each of four equidistant start locations, with an intertrial interval of 5 sec, for a total of 16 trials. One trial consisted of a rat placed on the edge of the cheese board, facing the wall at one of the four approximate starting locations. The start location was pseudorandomly determined for each trial. The rat was allowed to search for food until it found the correct hole or until 120 sec transpired. A camera mounted to the ceiling and a computer tracking system (San Diego Instruments) measured the distance traveled to find the correct hole. On trial 17, a probe trial was given. The food was removed and the animal was released from one of the start locations and allowed to explore the maze for 120 sec. The time spent in each quadrant was measured during the probe trial by the camera and tracking system.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc analyses when necessary, using a Student-Newman-Keuls test.

RESULTS

Contralateral lesions of the hippocampus and PC impair dry land water maze acquisition

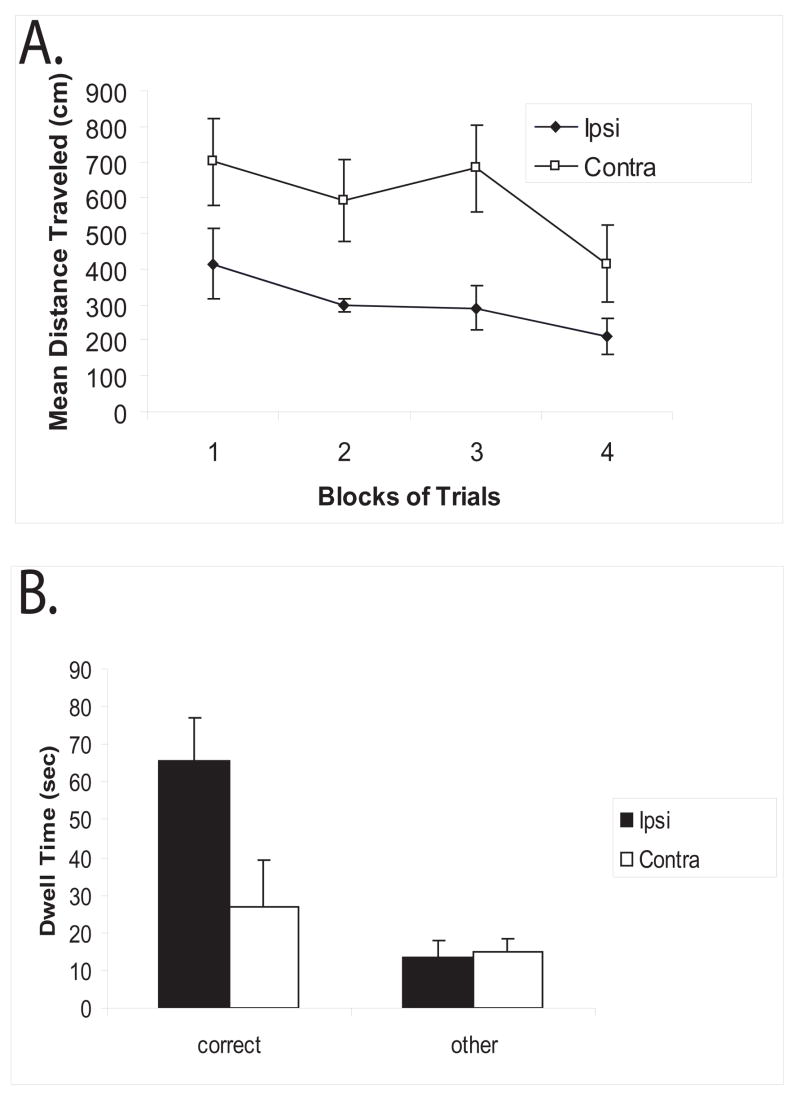

When unilateral lesions were placed in contralateral hemispheres within the dorsal hippocampus and posterior PC, an overall deficit in dry land water maze acquisition was observed when compared to unilateral lesions placed in ipsilateral hemispheres (Figure 3a). A repeated measures ANOVA was performed on the data with groups as the between-subjects variable and blocks of trials as the within-subjects variable. There was a significant main effect for the groups [F (1, 10) = 4.97; p<0.05] as well as blocks [F (3,30) = 5.97; p<0.003]; however, there was no significant interaction between groups and blocks [F (3,30) = 1.49; p>0.05].

Figure 3.

A: Acquisition of the dry-land water maze task. Results, shown as means +/− SEM, indicate significantly longer latencies to find the reward for the contralateral lesioned animals (Contra) compared to Ipsilateral lesioned animals (Ipsi). B: Probe trial data, shown as means +/− SEM, indicate that Ipsilateral lesioned animals spent significantly more time in the rewarded (correct) quadrant compared to the average time spent in the other quadrants, whereas Contralateral lesioned animals had similar dwell times.

Probe data indicate that ipsilateral lesioned animals spent significantly more time in the rewarded quadrant (“correct”) compared to the non-rewarded quadrants (“other”), whereas, the contralateral lesioned animals spent similar amounts of time in each quadrant (Figure 3b). A repeated measures ANOVA was performed on the data with groups as the between-subjects variable and time spent in each quadrant the within-subjects variable. There was a significant main effect for groups [F (1,10) = 11.66; p<0.005], as well as time spent in each quadrant [F (1,10) = 9.48; p<0.01]. Furthermore, there was a significant interaction between group and time in each quadrant [F (1,10) = 7.42; p<0.02]. Post-hoc analysis (Student-Newman-Keuls) performed on the interaction between groups and time spent in each quadrant revealed that the ipsilateral lesioned animals spent significantly more time in the rewarded quadrant than the non-rewarded quadrants (p<. 05). In addition, the ipsilateral lesioned animals spent significantly more time in the rewarded quadrant than did the contralateral lesioned animals (p<. 05). Finally, the contralateral lesioned animals were not significantly different in the amount of time spent in the rewarded and non-rewarded quadrants.

EXPERIMENT 3: REACTION-TO-CHANGE PARADIGM

METHODS

Animals

Sixteen male, Long-Evans rats (Simonsen Laboratories, Inc., Gilroy, CA, USA) approximately 4 months of age at the start of the experiment, weighing ~350 gm, served as subjects. Half of the rats used in the current study were used previously in Experiment 1a and the other half were used in Experiment 1b. Half of the rats had contralateral lesions, whereas, the other half had ipsilateral lesions. The rats were housed individually in plastic tubs located in a colony with a 12-hr light-dark cycle. All rats had free access to water and food for the duration of testing. All testing was conducted during the light portion of the light-dark cycle.

Apparatus

The same round cheeseboard maze that was used in Experiment 1 served as the test apparatus. A start box (24 cm long x 15 cm wide x 17 cm high) was placed on the maze surface, centered so that the door to the start box opened facing the center of the maze, with the posterior wall of the box placed along the edge of the maze. The box was equipped with a red Plexi-glass hinged top and a guillotine door that could be raised and lowered by the experimenter. In addition, a green curtain covered the maze to prevent the rats from being distracted by the holes in the maze. A video camera was positioned directly above the maze. All trials were videotaped and analyzed by an observer blind to the treatment groups.

Six different toy objects were used. Object A, a green rubber frog (10cm X 6cm); Object B, a green toy figure (“Oscar”, 7cm X 4cm); Object C, a yellow rubber ducky (9cm X 5cm); Object D, a yellow plastic vertical bar (11cm X 1.5cm); Object E, a white wooden bear (6cm X 4cm); and Object F, a blue plastic cup (10cm X 7cm). Objects B and D were attached to a washer (4 cm in diameter) to support the objects on the maze. A cork cap (3 cm in diameter) was attached to the bottom of each object to secure placement of the objects to the maze and prevent the animals from knocking over the objects during testing. The experimental procedures matched those used by Lee and colleagues (2005).

Testing

There were seven sessions lasting 6 min with an intersession interval of 3 min in which the rat was introduced to the cheese board with either 0 or 5 objects (e.g., Frog, duck, bear, tower, Oscar, or car). In all sessions, the start box was removed from the room by the experimenter as soon as the rat exited the box. Session 1 (Familiarization) involved exploration of cheese board without any objects present. In session 2 (Object introduction), the five objects (A-E) were introduced at pre-determined locations and the rat was free to explore. Session 3 (Habituation 1) involved the same object orientation as Session 2. Session 4 (Habituation 2) involved the same object orientation again. Session 5 (Reconfiguration) involved a reconfiguration of the stimuli, where Object E was moved to the position of Object D and Object D was displaced to a new spatial location. Session 6 (Habituation) involved the same orientation of objects as Session 5. Session 7 (novel object introduction) involved the introduction of a novel object, where in Object F replaced Object A and the rest of the objects remained the same as Session 6.

Data Analysis

The number of grid crossings for each group measured locomotor activity across the seven sessions and the sessions were blocked on the basis of the experimental manipulations (i.e., Block 1 = Session 1; Block 2 = Sessions 2–4; Block 3 = Sessions 5–6; Block 4 = Session 7). To measure habituation, a difference score was calculated by subtracting the time spent exploring each object during Session 4 from the time spent exploring the same object during Session 2. The average of the difference scores between Sessions 2 and 4 for all five objects became the ‘habituation index’. A ‘spatial mismatch index’ was calculated to quantify the amount of exploration for the two displaced objects; the sum of the exploration time for each displaced object (Objects D and E) during Session 4 was subtracted from the sum of the exploration time for those objects during Sessions 5, where higher scores indicate more exploration. A similar index was calculated for the non-displaced objects. An ‘object mismatch index’ was calculated by subtracting the average exploration time of Objects B-E from the time spent exploring the newly introduced Object F during Session 7.

A T-test compared the group effects on the ‘habituation index’ or ‘object mismatch index’. A separate T-test was performed on the ‘spatial mismatch index’ for displaced and non-displaced objects during Sessions 4–5; lesion group was the between-subjects variable. Activity level was compared by a repeated measures ANOVA with groups as the between subjects variable and blocked sessions as the within-subject variable. Finally, verification that the animals explored the reconfiguration and novel object more than the non-displaced/familiar objects was measured via a paired samples T-test.

RESULTS

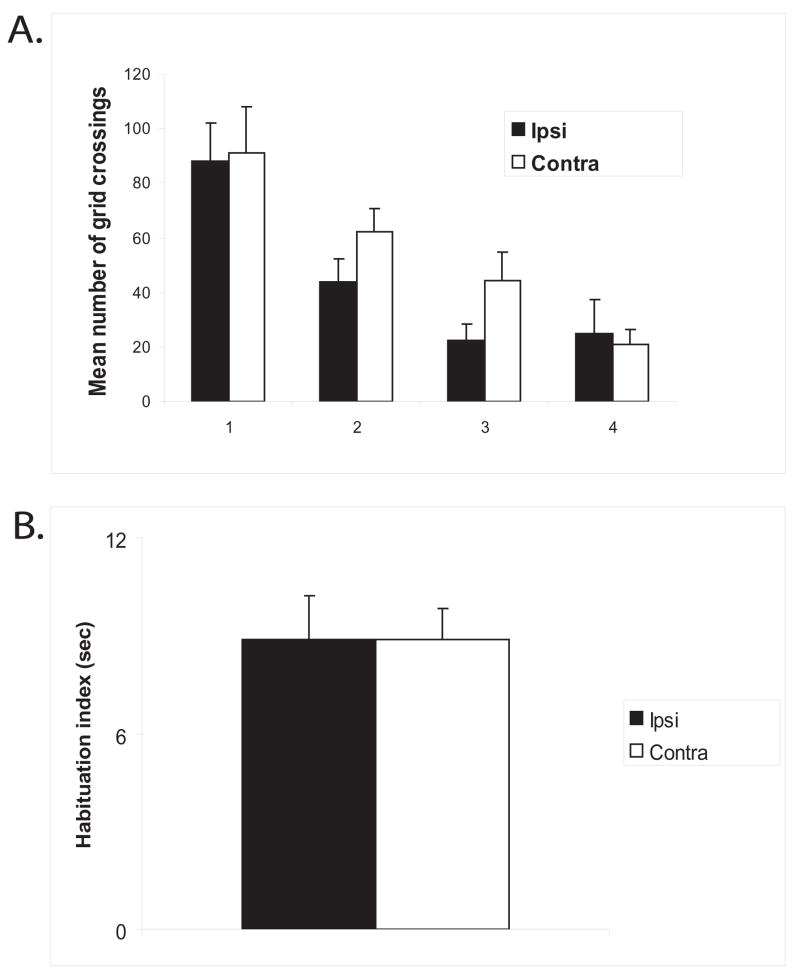

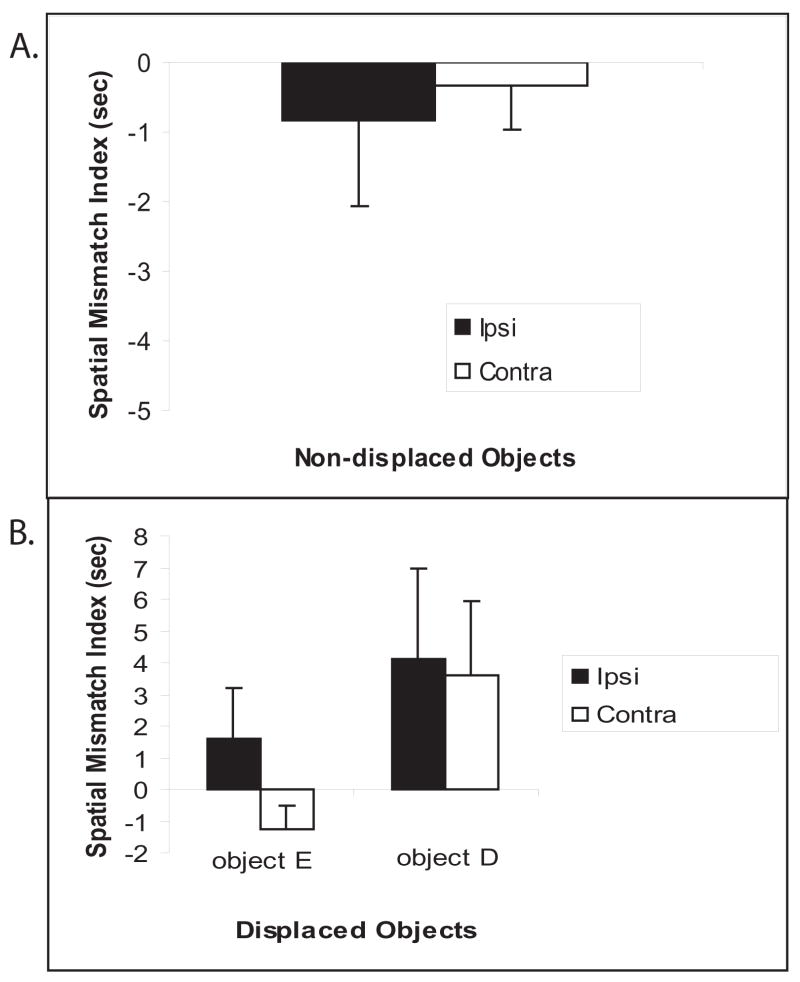

No differences between contralateral and ipsilateral lesions of the hippocampus and PC

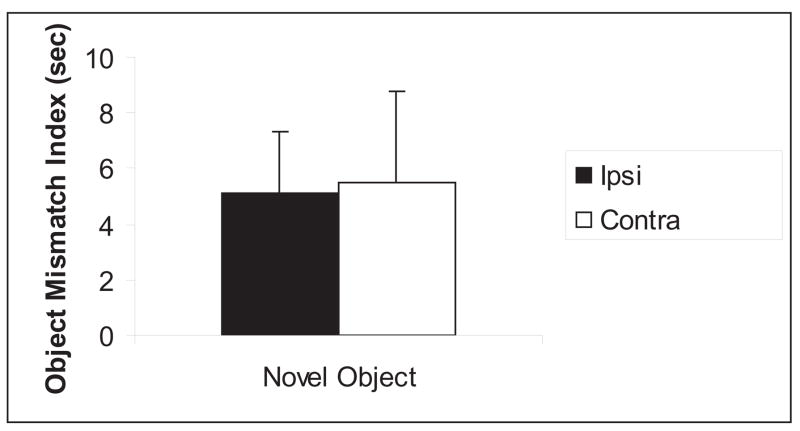

When unilateral lesions were placed in contralateral hemispheres within the dorsal hippocampus and PC, no deficits were observed on any of the measures when compared to unilateral lesions placed in ipsilateral hemispheres. A repeated measures ANOVA was performed on locomotor activity (measured by grid crossings, Figure 4a) with groups as the between-subjects variable and blocked sessions as the within-subjects variable. There was no significant main effect for the groups [F (1,8) = 0.10; p>0.05]; however, there was a significant main effect for blocked sessions [F (3,24) = 58.88; p<0.001], suggesting that both groups readily habituated to the environment. In addition, there was no significant interaction between groups and blocked sessions [F (3,24) = 1.50; p>0.05]. A T-test performed on the ‘habituation index’ (Figure 4b) revealed no significant differences between the groups [t (14) = 0.01; p>0.05], suggesting that both groups equally habituated to the objects in the environment. During the reconfiguration session (Session 5), both groups detected the spatial change and during Session 7, both groups detected the novel object. A T-test performed on the amount of time spent exploring the individual displaced objects (Object D and E) vs. the non-displaced objects (Objects A-C) revealed that during Session 5, the Ipsi group explored Object D more than the non-displaced objects [t (7) = 2.59; p>0.05]. Similarly, the Contra group explored Object D more than the non-displaced objects [t (7) = 2.81; p>0.05]. Conversely, a T-test performed on the spatial mismatch index for the non-displaced objects (Figure 5a) revealed no significant differences between the groups [t (14) = 0.93; p>0.05]. A T-test performed on the spatial mismatch index for the individual displaced objects (Figure 5b) revealed no significant differences for Object D [t (14) = 0.14; p>0.05], or Object E [t (14) = 1.64; p>0.05], suggesting no group differences in re-exploration of the displaced and non-displaced objects. A T-test performed on the amount of time spent exploring the novel object vs. the familiar objects during Session 7 revealed that the Ipsi group explored the novel object more than the familiar objects [t (7) = 2.63; p>0.05]. Similarly, the Contra group the novel object more than the familiar objects [t (7) = 2.48; p>0.05]. Finally, a T-test performed on the ‘object mismatch index’ (Figure 6) revealed no significant differences between the groups [t (14) = −0.10; p>0.05], suggesting no group differences in exploration of a novel object.

Figure 4.

A: Locomotor activity, shown as means +/− SEM and measured by grid crossings, across blocks. Note no differences between groups. B: Habituation index, shown as means +/− SEM and measured by the decrease in exploration of the objects between Sessions 2 and 4. Note no differences between the groups.

Figure 5.

Spatial novelty detection, shown as means +/− SEM. A: Spatial mismatch index for the non-displaced objects. B: Spatial mismatch index for the individual displaced objects. Note no differences between the groups.

Figure 6.

Object novelty detection, shown as means +/− SEM and measured by the exploration time for a new Object F that replaced Object A in Session 7. Note no differences between the groups.

DISCUSSION

Although the hippocampus and PC are not directly connected anatomically (Burwell, 2000; Lavenex and Amaral, 2000; Witter et al., 2000), behavioral data clearly indicate that the hippocampus and PC process spatial information. What is not clear, however, is whether or not the hippocampus and PC interact during spatial information processing. The data from Experiments 1 and 2 indicate that the hippocampus and PC interact during object-place paired associate learning and acquisition of the dry-land water maze task; however, data from Experiment 3 indicate that the hippocampus and PC need not interact during a reaction-to-change paradigm.

Long , Melem and Kesner(1998) suggested that the PC represents associations among two or more stimuli, as long as one of those stimuli is spatial in nature. These authors also suggest that the role of the PC could be to ‘bind’ or maintain an association between landmark and spatial location information, an idea derived from the Feature Integration Theory (Treisman and Gelade, 1980). Computational models of hippocampal function (O’Reilly and McClelland, 1994; Rolls, 1990; 1996) suggest that the hippocampus is also responsible for arbitrary associations; however, Gilbert and Kesner (2002) found that hippocampal lesions impaired associations of a spatial nature (i.e., object-place), but not non-spatial (i.e., object-odor) associations. Therefore, the PC and hippocampus represent arbitrary associations of a spatial nature. As suggested elsewhere (see Kesner and Rogers, 2004; Rogers and Kesner, 2006), the hippocampus and PC process different components of spatial information; as a result, object-place paired associate learning (Experiment 1) and the dry-land water maze task (Experiment 2) require hippocampal-PC interaction based on the respective contribution of each region to solve the task at hand. In support of this view, Rogers and Kesner (2006) found that the dorsal hippocampus and posterior PC acquire spatial information in parallel, with potential interactions necessary for consolidation and/or long-term storage. Thus, spatial tasks that require multiple trials across several days of consolidation and/or storage require hippocampal-PC interaction.

Curiously, the findings in Experiment 3 suggest that reacting to novel stimuli in the environment somehow differs from paired-associate learning and spatial navigation. Given the nature of the experiment (i.e., 1 d of testing), it is possible that such short-term encoding, that is to say, within one day of testing, might not require an interaction that longer-term learning, such as paired associate learning and/or dry-land water maze testing, may require. Alternatively, Save and colleagues (1992) reported that bilateral lesions of the PC or hippocampus disrupted an animal’s ability to react to a spatial change (when one previously explored object moved to a new location); however, lesions of the PC or hippocampus did not affect an animal’s ability to react to novel stimuli. Thinus-Blanc et al. (1996) suggested that the participation of the PC in detecting spatial novelty may depend on the functionality of the hippocampus; however, the present findings suggest that the hippocampus and PC need not interact during this task. Recent findings from Parron and colleagues (2006) showed that entorhinal cortex-hippocampal interactions were necessary for the detection of a spatial change, but not a novel object. Furthermore, these authors found that interactions were not necessary for successful spatial navigation. Thus, for the detection of spatial novelty, it is likely that the hippocampus interacts with the entorhinal cortex, whereas, during spatial navigation (i.e., dry-land water maze task, object-place paired associate learning) the hippocampus interacts with the PC.

Yet another interpretation could be the nature of the spatial displacement during the reconfiguration session. During the spatial reconfiguration, Object E moved to the location previously occupied by Object D, whereas Object D was displaced to a novel location. The displacement of Object E could be thought of as a ‘topological’ shift, based on a relationship of connectedness among the objects (Hermann & Poucet, 2001; Poucet 1993). The displacement of Object D could be thought of as a ‘metric’ shift, based on the relationship of distance and angles (Gallistel, 1990; Poucet, 1993). Recently, Goodrich-Hunsaker and colleagues (2005) found that rats with bilateral lesions of the PC did not re-explore topological changes, but were unaffected during metric shifts. Conversely, rats with bilateral hippocampal damage did not re-explore metric shifts, but were unaffected by topological changes. In the present study, both Ispi and Contra groups significantly re-explored Object D, but not Object E, which would suggest that unilateral damage to PC is sufficient to disrupt topological information processing, whereas unilateral damage to hippocampus is not sufficient to disrupt metric information processing. Furthermore, the finding that both groups readily explored a spatial change is surprising given that bilateral lesions of either area will result in impairments (Save et al., 1992a). This would suggest that although no interaction is necessary, intact functioning of at least one hemisphere is necessary for the detection of the spatial change. It is important to note, however, that these animals had previous behavioral experience. Although there was no food reward and the animals were not food-deprived, the previous experience of the animals may contribute to the lack of effects observed in Experiment 3. Future studies will explore the contribution of previous behavioral experience to the detection of novelty.

In sum, the present results indicate that the dorsal hippocampus and posterior PC interact during spatial tasks that require multiple training days, such as object-place paired associate learning and acquisition of the dry-land water maze task. Whereas previous data show that both regions are necessary for the detection of spatial novelty, the present results indicate that no interaction is necessary, unlike the necessary interactions between the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex (Parron et al., 2006). Given that the hippocampus and PC connect through intermediate sources such as entorhinal cortex, future studies hope to investigate the dynamic among these regions to discern the nature of the interaction between the dorsal hippocampus and posterior PC.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NSF Grant IBN-0135273 and NIH Grant R1MH065314.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson RA. Multimodal integration for the representation of space in the posterior parietal cortex. In: Burgess, Jeffery, O’Keefe, editors. The Hippocampal and Parietal Foundations of Spatial Cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Burwell R. The Parahippocampal region: corticocortical connectivity. In: Scharfman, Witter, Schwarcz, editors. The Parahippocampal Region. New York: The New York Academy of Sciences; 2000. pp. 25–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoteau W, Kesner R. Effects of hippocampal and parietal cortex lesions on the processing of multiple-object scenes. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1998;112:68–82. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMattia B, Kesner R. Spatial cognitive maps: differential role of parietal cortex and hippocampal formation. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1988;102:471–480. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.4.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR. The organization of learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP. Role of the rodent hippocampus in paired-associate learning involving associations between a stimulus and a spatial location. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;116:63–71. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich-Hunsaker NJ, Hunsaker MR, Kesner RP. Dissociating the role of the parietal cortex and dorsal hippocampus for spatial information processing. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119:1307–1315. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann T, Poucet B. Exploratory patterns of rats on a complex maze provide evidence for topological coding. Behavioral Process. 2001;54:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(00)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Farnsworth G, Kametani H. Role of parietal cortex and hippocampus in representing spatial memory. Cerebral Cortex. 1992;1:367–373. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.5.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Giles R. Neural circuit analysis of spatial working memory: Role of pre-and parasubiculum, medial and lateral entorhinal cortex. Hippocampus. 1998;8:416–423. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:4<416::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Lee I, Gilbert P. A behavioral analysis of hippocampal function based on a subregional analysis. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2004;15:333–51. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2004.15.5.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Rogers J. An analysis of independence and interactions of brain substrates that subserve multiple attributes, memory systems, and underlying processes. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2004;82:199–215. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavenex P, Amaral D. Hippocampal-neocortical interaction: a hierarchy of associativity. Hippocampus. 2000;10:420–430. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<420::AID-HIPO8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Hunsaker MR, Kesner RP. The role of hippocampal subregions in detecting spatial novelty. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119:145–53. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J, Mellem J, Kesner R. The effects of parietal cortex lesions on an object/spatial location paired-associate task in rats. Psychobiology. 1998;26:128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Marr D. Simple memory: a theory for archicortex. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B Biol Sci. 1971;262:23–81. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1971.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser E, Moser MB, Andersen P. Spatial learning impairment parallels the magnitude of dorsal hippocampal lesions, but is hardly present following ventral lesions. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:3916–3925. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03916.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J, Dostrovsky J. The hippocampus as a spatial map: Preliminary evidence from unity activity in the freely moving rat. Brain Research. 1971;34:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe J. Place units in the hippocampus of the freely moving rat. Experimental Neurology. 1976;51:78–109. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly RC, McClelland JL. Hippocampal conjunctive encoding, storage, and recall: avoiding a trade-off. Hippocampus. 1994;4:661–82. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olton D. Memory functions and the hippocampus. In: Seifert W, editor. Neurobiology of the Hippocampus. San Deigo: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 348–352. [Google Scholar]

- Parron C, Poucet B, Save E. Cooperation between the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in spatial memory: A disconnection study. Behavioral Brain Research. 2006;170:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poucet B. Spatial cognitive maps in animals: New hypotheses on their structure and neural mechanisms. Psychological Review. 1993;100:163–182. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JL, Kesner RP. Lesions of the hippocampus or parietal cortex differentially affect spatial information processing. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006 doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.4.852. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. The representation of space in the primate hippocampus, and its role in memory. In: Ishikawa K, McGaugh J, Sakata H, editors. Brain Processes and Memory. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1996. pp. 203–227. [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET. Spatial memory, episodic memory, and neural network functions in the hippocampus. In: Squire LR, Lindenlaub E, editors. The Neurobiology of Memory. New York: Schattauer Verlag; 1990. pp. 445–470. [Google Scholar]

- Save E, Paz-Villagran V, Alexinsky T, Poucet B. Functional interaction between the associative parietal cortex and hippocampal place cell firing in the rat. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;21:522–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save E, Poucet B. Hippocampal-parietal cortical interactions in spatial cognition. Hippocampus. 2000a;10:491–499. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<491::AID-HIPO16>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Save E, Poucet B, Foreman N, Thinus Blanc C. Object exploration and reactions to spatial and nonspatial changes in hooded rats following damage to parietal cortex or hippocampal formation. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1992a;106:447–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffenach HA, Witter M, Moser MB, Moser EI. Spatial memory in the rat requires the dorsolateral band of the entorhinal cortex. Neuron. 2005;45:301–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinus-Blanc C, Save E, Rossi-Arnaud C, Tozzi A, Ammassari-Teule M. The difference shown by C57BL/6 and DBA/2 inbred mice in detecting spatial novelty are subserved by a different hippocampal and parietal cortex interplay. Behavioral Brain Research. 1996;80:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treisman A, Gelade G. A feature integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology. 1980;12:97–136. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(80)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groen T, Kadish I, Wyss JM. Retrosplenial cortex lesions of area Rgb (but not of area Rga) impair spatial learning and memory in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 2004;154:483–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton EC, Baird A, Morgan A, Muir JL, Aggelton JP. The conjoint importance of the hippocampus and anterior thalamic nuclei for allocentric spatial learning: Evidence from a disconnection study in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:7323–7330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07323.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witter M, Naber P, van Haeften T, Machielsen W, Rombouts S, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Lopes da Silva F. Cortico-hippocampal communication by way of parallel parahippocampal-subicular pathways. Hippocampus. 2000;110:398–410. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<398::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]