Abstract

The authors examined the relations of maternal supportive parenting to effortful control and internalizing problems (i.e., separation distress, inhibition to novelty), externalizing problems, and social competence when toddlers were 18 months old (n = 256) and a year later (n = 230). Mothers completed the Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale, and their sensitivity and warmth were observed. Toddlers' effortful control was measured with a delay task and adults' reports (Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire). Toddlers' social functioning was assessed with the Infant/Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment. Within each age, children's regulation significantly mediated the relation between supportive parenting and low levels of externalizing problems and separation distress, and high social competence. When using stronger tests of mediation, controlling for stability over time, the authors found only partial evidence for mediation. The findings suggest these relations may be set at an early age.

Keywords: toddlers' effortful control, maternal socialization, social functioning, problem behaviors

A major goal of current research has been to understand individual differences in young children's problem behaviors and social competence. Although researchers have identified parenting and children's temperament as factors that play an important role in children's socioemotional functioning (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Rothbart & Bates, 2006), few efforts have been made to study these links in very young children. Despite the lack of attention to this issue, there is some evidence that internalizing and externalizing problems in toddlerhood are stable (Keenan, Shaw, Delliquadri, Giovannelli, & Walsh, 1998; Smith, Calkins, Keane, Anastopoulos, & Shelton, 2004) and may have implications for later maladjustment (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000; Keenan et al., 1998). The purpose of this study was to examine the relations of toddlers' temperamental effortful control and maternal socialization to social functioning at 18 months of age (Time 1 [T1]) and a year later (Time 2 [T2]).

Effortful Control

There is a growing body of research on the construct of emotion regulation as it pertains to children's social functioning. Although the definition of emotion regulation varies, some researchers have conceptualized emotion regulation in terms of children's effortful or voluntary control as opposed to more reactive forms of control (Eisenberg & Spinrad, 2004; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). Effortful control has been defined as “the efficiency of executive attention, including the ability to inhibit a dominant response and/or to activate a subdominant response, to plan, and to detect errors” (Rothbart & Bates, 2006, p. 129). Effortful control is characterized by the ability to voluntarily focus and shift attention and to voluntarily inhibit or initiate behaviors, and includes behaviors such as delaying; these processes are integral to emotion regulation (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Kieras, Tobin, Graziano, & Rothbart, 2005; Saarni, Campos, Camras, & Witherington, 2006). For example, effortful attentional processes can be used to regulate emotions, such as turning away from something distressing (Rothbart, Ziaie, & O'Boyle, 1992). Empirical work has shown that orienting behaviors serve a regulatory function during an angerinducing task in infancy (Stifter & Braungart, 1995), and effortful control has been linked to the regulation of emotion during disappointment tasks (Kieras et al., 2005). Indeed, effortful control is believed to reflect dispositional differences in regulation, although this regulation can be used to manage emotional, as well as less emotional, facets of functioning. Thus, in comparison to emotion regulation, the construct of effortful control is viewed as a broader construct that includes an array of skills that can be used to manage emotion and its expression (Eisenberg, Hofer, & Vaughan, 2007; Gross & Thompson, 2007; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). In general, effortful control is viewed as a dispositional characteristic that reflects individuals' capacities to regulate their emotions and behaviors (Caspi & Shiner, 2006).

Whereas effortful control is seen as reflecting voluntary behavior, reactive control refers to aspects of functioning such as impulsivity and behavioral inhibition (Eisenberg, Smith, Sadovsky, & Spinrad, 2004; Eisenberg & Spinrad, 2004). Reactive control refers to behavior in which individuals are undercontrolled and are “pulled” toward rewarding situations (i.e., impulsivity) or behavior in which individuals are overcontrolled and are wary in response to novelty, inflexible, and overconstrained (i.e., behavioral inhibition). Reactive control is not considered to be part of self-regulation (Eisenberg et al., 2007; Eisenberg & Spinrad, 2004), and reactive undercontrol and effortful control are generally negatively related (Aksan & Kochanska, 2004; Eisenberg, Spinrad, et al., 2004). Reactive processes seem to originate primarily in subcorticol systems (Gray, 1991), whereas executive attention, the basis of effortful control, is believed to be situated primarily in the cortex (e.g., the anterior cingulated, lateral ventral, and prefrontal cortex; see Posner & Rothbart, 2007).

In terms of the development of these constructs, effortful control is thought to emerge in late infancy and to develop rapidly during the toddler years. Improvements in inhibitory control are exhibited between 6 and 12 months of age (Putnam & Stifter, 2002), and it is believed that more mature effortful control is partially evident by 18 months of age and continues to improve greatly from 22 to 36 months of age (Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000; Mezzacappa, 2004; Posner & Rothbart, 1998; Reed, Pien, & Rothbart, 1984; Rueda et al., 2004). Moreover, individual differences in toddlers' effortful control are relatively stable in the early years (Kochanska et al., 2000) and from early childhood to adolescence and adulthood (Ayduk et al., 2000; Shoda, Mischel, & Peake, 1990). On the other hand, reactive control likely develops earlier than effortful control and may be intimately related to emotional reactions, such as fear, seen in infancy (Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

The Relations of Effortful Control to Children's Social Functioning

There is reason to expect that effortful control has consequences for children's adjustment and maladjustment. Specifically, when children are low in effortful control, they are likely to exhibit negative outbursts, to behave inappropriately with peers and adults, and to behave aggressively. Consistent with these expectations, researchers have found that low effortful control is associated with and predicts behavior problems in preschool and school-aged populations (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2005; Eisenberg, Spinrad, et al., 2004; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003; Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, & Wellman, 2005). Although the majority of work has been done with older children, Kochanska and Knaack (2003) found negative relations between effortful control at ages 22, 33, and 45 months and later externalizing problems at 73 months. Thus, we expected a negative relation between toddlers' effortful control and their externalizing problem behaviors. In addition, because many studies with young children have included a broad array of items to measure adjustment problems (some of which may tap temperament, such as activity level), we tested these relations using a purer measure of externalizing problems.

The links between effortful control and internalizing problems have been more complex. For example, Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al. (2001) found that internalizing children aged from 4.5 to 7 years were low in attentional regulation (one component of effortful control) but no different from children without behavior problems in terms of inhibitory control (another component of effortful control). Moreover, internalizing problems in young toddlers are rather rare (Carter, Briggs Gowan, Jones, & Little, 2003) and measures may suffer from overlap with indices of temperament. Thus, in this study, we separated measures that reflected internalizing problems in toddlers (separation distress) from those that likely measure elements of temperament or reactive overcontrol (inhibition to novelty). Because separation distress probably involves the inability to control negative emotions such as anxiety or sadness/depression, we expected children with this type of internalizing problem to be relatively low in effortful control (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Kochanska, Coy, Tjebkes, & Husarek, 1998).

Children's effortful control also is thought to contribute to positive outcomes in children. Children who are able to control their attention and behavior are expected to manage their emotions, plan their behavior, and develop and utilize skills needed to get along with others and to engage in socially appropriate behavior (Eisenberg et al., 2007). Indeed, effortful control has been related to higher levels of emotion regulation (Rothbart et al., 1992), sympathy and prosocial behavior (Diener & Kim, 2004; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994), internalized conscience (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003), committed compliance (Kochanska, Coy, & Murray, 2001), and social competence (Calkins, Gill, Johnson, & Smith, 1999). Thus, we anticipated a positive relation between effortful control and social competence in our toddler sample.

Rothbart and Bates (2006) have noted the need to examine temperament in relation to multiple dimensions of adjustment. Thus, we tested the links between effortful control and early externalizing problems, two types of internalizing problems, and social competence in a sample of young children and examined whether the relations were apparent over time.

The Relations of Maternal Emotion-Related Socialization to Children's Effortful Control and Social Functioning

Although children's effortful control reflects constitutionally based individual differences in temperament, the environment also plays a role in the development of these characteristics (Goldsmith, Buss, & Lemery, 1997; Rothbart & Bates, 2006). The role of caregivers may be particularly salient for toddlers because young children have very limited self-regulatory abilities, and parents are viewed as sources of early emotion regulation (Kopp, 1989). Eisenberg, Cumberland, and Spinrad (1998) proposed that some of the relations between parenting and children's outcomes may be mediated through children's emotion-related regulation (i.e., processes such as effortful control). According to this heuristic model, parents who are warm and sensitive and who respond to children's emotions in appropriate ways rear better regulated children, who in turn are less likely to develop problem behaviors and are more likely to be socially competent.

A number of investigators have argued that children acquire regulatory abilities within a network of social relationships, particularly in interactions with their parents (Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1997). There are multiple ways in which parents may foster increased effortful control. First, mothers may serve as models for ways to deal with emotions and behaviors, such that mothers who are more disapproving or hostile may model dysregulation, whereas mothers who are more positive and supportive likely model more constructive ways to manage stress (Halberstadt, Crisp, & Eaton, 1999). Second, when mothers respond to children's emotions in unsupportive ways, such as punishing or displaying disapproval, children may experience heightened arousal, which is likely to interfere with their ability to focus and shift attention and regulate behavior (Hoffman, 2000). In addition, sensitive, warm, and supportive mother–infant interactions have been seen as beneficial to the mother–child attachment relationship, which in turn may influence the child's regulation abilities (Thompson, 2006). Finally, when mothers are supportive in regard to children's emotions, children may be more likely to internalize their mothers' goals/agendas; thus, these children may be more motivated to learn from interactions with their parents (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994; Hoffman, 1982). Consequently, mothers' reactions and responsiveness to their children's emotions are likely to provide important opportunities for the socialization of effortful control (Spinrad, Stifter, Donelan McCall, & Turner, 2004).

Studies of the socialization of regulation in the early years have often focused on maternal sensitivity, a measure that taps the mother's responsiveness to her child's cues and the appropriateness of her responses to the child's emotions. Kopp (1989) has suggested that when a mother responds promptly and effectively to her infant's distress, this experience modulates the infant's immediate arousal and functions as a learning experience for the infant. Indeed, maternal sensitivity has been linked with infants' and young children's self-regulation and a reduction in negative emotion (Fish, Stifter, & Belsky, 1991; Spinrad, Stifter, et al., 2004). In toddlerhood, children with more responsive mothers have been found to display higher effortful control (Kochanska et al., 2000).

Related to maternal sensitivity, interactions involving maternal warmth, characterized by positive exchanges and affect, also may foster children's developing regulatory skills. Warm parents are likely to allow their children to express their feelings and use emotion-coaching, and their children may be less likely to become overaroused in distressing situations (Gottman et al., 1997; Katz, Wilson, & Gottman, 1999). Consistent with this notion, maternal warmth/support observed in the early years has predicted children's ability to shift attention at 3.5 years of age (Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, & Lukon, 2002), and parental warmth has been linked to children's appropriate affect expression (Isley, O'Neil, Clatfelter, & Parke, 1999) and regulation of positive affect (Davidov & Grusec, 2006).

Moreover, parents' reactions to children's negative emotions likely provide rich opportunities for children to learn strategies for controlling their emotions and behavior. Supportive parental reactions may provide help in reducing children's negative emotions, contribute to children's abilities to understand emotions, or directly teach ways to deal with future negative situations. On the other hand, mothers who use nonsupportive strategies may model and induce more aroused and dysregulated behaviors (Cole, Michel, & Teti, 1994), which can undermine the learning of socially appropriate behavior (Hoffman, 2000). Indeed, mothers' nonsupportive responses to negative emotions have been related to lower emotion knowledge (Davidov & Grusec, 2006; Denham, Mitchell-Copeland, Strandberg, Auerbach, & Blair, 1997) and emotion regulation (Spinrad, Stifter, et al., 2004), although few investigators have explicitly studied this relation in toddlers. In this study, mothers' observed sensitivity/warmth and mothers' reported reactions to their toddlers' negative emotions were used to measure mothers' supportive emotion-related socialization practices. We expected maternal supportive parenting to be positively related to toddlers' effortful control.

Finally, consistent with Eisenberg et al.'s (1998) heuristic model, we predicted that effortful control would mediate the relations between parenting and children's social functioning. Only a few investigators have tested whether effortful control mediates the relation of parenting to child outcomes, and there has been some support for this process in work with older children (Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2003), but it has rarely been tested in work with toddlers. In one recent exception, Kochanska and Knaack (2003) found that toddlers' effortful control mediated the relation between maternal power assertion and children's conscience, providing some support for studying these mediational processes in younger children. The main goal of the current study was to examine whether toddlers' effortful control mediates the relation between mothers' supportive socialization strategies and four constructs reflecting the quality of toddlers' socioemotional functioning (i.e., separation distress, inhibition to novelty, externalizing, and social competence).

If mediation is found, it is also important to determine if this process is evident in early toddlerhood and/or in later toddlerhood. In this study, we examined whether the predicted patterns could be seen at both 18 and 30 months of age (concurrent mediation) and whether the patterns at 30 months could be predicted by the 18-month behaviors (longitudinal mediation). We also tested longitudinal mediation after controlling for stability in the constructs over time. Given that effortful control may still be relatively immature at 18 months of age, we anticipated only moderate stability in the constructs over the 1-year period. We also expected that early maternal socialization would account for later effortful control and that early effortful control would predict lower problem behaviors and higher social competence over time (even after controlling for stability in the constructs). These findings would indicate that the processes are still developing over time and that the relations are not firmly established at a very young age. On the other hand, if mediation is evident in the concurrent data but does not occur when we control for stability in the constructs, it is possible that the relations are set in very early development or that there was only limited change in the relations over a 1-year period.

In summary, in this study, we examined the relations of maternal supportive parenting to toddlers' effortful control and social functioning at 18 months of age and 1 year later. We began the study when children were quite young because effortful control is thought to make significant improvements in the 2nd year of life, and toddlers' problem behaviors have been found to predict maladjustment years later. We chose to measure children's internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors because these problems often reflect children's deficiencies in controlling emotions and behavior. In addition, children's effortful control likely facilitates social competence. Finally, we used multiple reporters and included observational measures of toddlers' effortful control and maternal supportive parenting.

Method

Participants

Participants were part of a longitudinal study of toddlers' emotions, regulation, and social functioning. Participants were recruited at birth through three local hospitals in a large metropolitan area in the Southwest. All infants were healthy, full-term, and from adult parents. The first laboratory visit was at approximately 18 months of age (T1), and we repeated the laboratory visit a year later (T2).

The initial assessment involved 256 toddlers and their mothers (including 9 families who participated only by mail; 141 boys, 115 girls; ages 16.8 to 20.0 months, M = 17.8 months). At T2, 230 toddlers and their mothers participated (including 14 families who participated only by mail; 128 boys, 102 girls; ages 27.2 to 32.0 months, M = 29.8 months). In terms of ethnicity, 77% of children were non-Hispanic and 23% were Hispanic. In addition, 81% of the children were Caucasian, although African Americans (5%), Native Americans (4%), Asians (2%), and Pacific Islanders (less than 1%) were also represented (2% identified themselves as “more than one race,” and 5% did not report race). Annual family income ranged from less than $15,000 to over $100,000, with the average income at the level of $45,000 to $60,000. Parents' education ranged from eighth grade to the graduate level; the average number of years of formal education completed by both mothers and fathers was approximately 14 years (2 years of college). At the 18-month assessment, 59% of all mothers were employed (82% of these full-time). Eighty-five percent of the parents were married and had been married from less than 1 year to 25 years (M = 5.9 years, SD = 3.8). Fifty-eight percent of the children had siblings, and 42% of the children were firstborns.

The individuals who participated at both time points (n = 223) were compared with those who were lost because of attrition (n = 33) on the T1 demographic and study variables. In terms of demographic variables, families who were lost because of attrition were at least marginally lower on family income (M = 3.44; 3 = between $30,000 and $45,000; 4 = between $45,000 and $60,000) and mother education (M = 3.68; 3 = high school graduate; 4 = some college) than were those who remained in the study (M = 4.16 and 4.36), t(226) = −1.97, p < .06, and t(238) = −3.43, p <.01, for income and education, respectively.

Out of 19 study variables, children who remained in the study were also seen by caregivers as lower in externalizing problem behaviors at T1 (M = 1.49) than were those who dropped from the study (M = 1.69), t(171) = 2.50, p < .02, and were seen by fathers as higher in social competence (M = 2.20) than were those who dropped out of the study (M = 2.08), t(194) = −2.04, p < .05. In addition, mothers who remained in the study reported lower on nonsupportive reactions to negative emotions than did those who dropped out of the study (Ms = 2.70 and 3.10, respectively), t(243) = 2.36, p < .02. Finally, toddlers who remained in the study had better delay ability (M = 2.69) than did those who dropped from the study (M =1.87), t(236) = 2.29, p < .03.

Procedures

At both time points, mothers and fathers were sent a packet of questionnaires by mail to complete and to bring to the laboratory visit (fathers were sent a shorter packet that did not include temperament assessments). Toddlers and mothers came to a laboratory on campus to participate in the laboratory sessions. As part of a series of tasks, mothers were observed interacting with their toddler during both free play and challenging puzzle tasks. In addition, toddlers' effortful control was assessed during a delay of gratification task. Mothers completed additional questionnaires in the laboratory (including a measure of reactions to children's negative emotions). At the end of the session, the participants were paid. In addition, mothers were asked to give permission for questionnaires to be sent to the child's nonparental caregiver (or another adult who knew the child well). Caregiver questionnaire packets were sent and returned through the mail. At T1, 200 fathers and 173 caregivers returned questionnaire packets; at T2, 161 fathers and 152 caregivers returned questionnaire packets.

Measures

Mothers' responses to negative emotion

At both T1 and T2, mothers' responses to their toddlers' negative emotions were assessed with the Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale (Spinrad, Eisenberg, Kupfer, Gaertner, & Michalik, 2004). This measure was adapted from the Coping With Children's Negative Emotions Scale (Eisenberg, Fabes, & Murphy, 1996). This instrument presents parents with 12 hypothetical situations in which their toddler is upset, distressed, or angry, and mothers' rated the likelihood of responding to the scenario in each of seven possible ways. For example, one item was “If my child is going to spend the afternoon with a new babysitter and becomes nervous and upset because I am leaving him, I would …” The measure consisted of seven subscales including (a) Distress Reactions (“feel upset or uncomfortable because of my child's reactions”; αs = .77 and .81), (b) Punitive (“tell my child that he won't get to do something else enjoyable, such as going to the playground or getting a special snack, if he doesn't stop behaving that way”; αs = .78 and .81), (c) Minimizing Reactions (“tell him that it's nothing to get upset about”; αs = .84 and .85), (d) Expressive Encouragement (“tell my child that it's ok to be upset”; αs =.92 and .93), (e) Emotion Focused (“distract my child by playing and talking about all of the fun he will have with the sitter”; αs = .75 and .76), (f) Problem Focused (“help my child think of things to do that will make it less stressful, like calling him once during the afternoon”; αs = .79 and .82), and (g) Granting the Child's Wish (“change my plans and decide not to leave my child with the sitter”; αs = .67 and .68). In addition, we gathered test–retest reliability on a subsample of mothers (n = 48) at T1 who completed the scale twice (separated by 2 to 4 months); significant stability in the scales over the short time period, rs(46) = .65 to .81, was found.

To create larger composites, we conducted a principal components factor analyses (with oblique rotation) using the seven subscales. Two subscales (Granting the Child's Wish and Distress Reactions) did not factor with any of the other subscales; thus, these two subscales were removed. A subsequent principal components analysis with the remaining five subscales was conducted, and two factors with Eigenvalues greater than 1 emerged (accounting for a total of 68% of the variance at T1 and 69% of the variance at T2). The first factor accounted for 39% of the variance at T1 and 41% of the variance at T2 and consisted of the problem-focused, emotion-focused, and expressive-encouragement subscales (reflecting supportive strategies). The second factor appeared to reflect unsupportive strategies (accounting for 28% of the variance at both time points) and included the minimizing and punitive reaction subscales. The items on each scale were averaged to create the supportive and nonsupportive subscales.

Maternal observed sensitivity and warmth

At both T1 and T2, maternal sensitivity was assessed during two mother–toddler interactions in the laboratory. First, a free-play interaction was observed in which mothers were presented with a basket of toys and asked to play as they normally would at home for 3 min. Second, a teaching paradigm was used in which mothers and toddlers were presented with a difficult puzzle (animal and geometric shapes at T1 and pegs/geometric shapes at T2). Mothers were instructed to “teach their child to complete the puzzle” and given 3 min to complete the task. Mothers were rated for sensitivity on a 4-point scale every 15 s for the free play and every 30 s for the puzzle task (Fish et al., 1991). Maternal sensitivity to the toddler was based upon behavioral evidence of being appropriately attentive to the toddler as well as appropriately and contingently responsive to his/her affect, interests, and abilities (1 = no evidence of sensitivity; 2 = minimal sensitivity; 3 = moderate sensitivity; 4 = mother was very aware of the toddler, contingently responsive to his or her interests and affect, and had an appropriate level of response/stimulation). Interrater reliability was assessed on approximately 25% of the sample and was .81 and .86 for the free play at T1 and T2 and .81 and .82 for the puzzle task at T1 and T2, respectively (Pearson correlations). Maternal sensitivity was positively correlated between the two tasks at each age, r(243) = .18 and r(214) = .27, ps < .01, at T1 and T2, respectively. Thus, to reduce the number of indicators and increase the reliability of the construct, a composite of maternal sensitivity was created by averaging the scores across the free play and puzzle task.

In addition, we examined maternal warmth during the teaching task (coded every 30 s). Maternal warmth was based upon mothers' levels of friendliness, displays of closeness, encouragement, and positive affect with the child. In addition, this code included the amount of physical affection and the quality of the mothers' tone/conversation (1 = no evidence of warmth; 2 = minimal warmth; 3 = moderate warmth;4 = engaged with the child for much of the time and touched the child in a positive way; 5 = very engaged with the child, positive affect was predominant, and the mother was physically affectionate). Interrater reliability was conducted on approximately 25% of the sample and was .83 at T1 and .73 at T2 (Pearson correlations).

Effortful control

At T1 and T2, toddlers' effortful control was assessed with the Attention-Focusing, Attention-Shifting, and Inhibitory-Control subscales of the Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire (Putnam, Gartstein, & Rothbart, 2006) and with a frequently used behavioral measure of observed delay ability. Mothers and nonparental caregivers rated each item on a 7-point scale (1 = never; 7 = always). The Attention-Focusing subscale consisted of 12 items assessing toddlers' ability to concentrate on a task (e.g., “When playing alone, how often did your child play with a set of objects for 5 minutes or longer at a time?”; αs = .76 and .79 for mothers and caregivers, respectively, at T1 and .81 and .85 for mothers and caregivers, respectively, at T2). The Attention-Shifting subscale consisted of 12 items assessing toddlers' ability to move attention from one activity to another (e.g., “During everyday activities, how often did your child seem able to easily shift attention from one activity to another?”; αs = .69 and .76 for mothers and caregivers, respectively, at T1 and .73 and .71 for mothers and caregivers, respectively, at T2). The Inhibitory-Control subscale included 12 items used to assess toddlers' ability to control their behavior, (e.g., “When told ‘no,’ how often did your child stop an activity quickly?”; αs = .81 and .90 for mothers and caregivers, respectively, at T1 and .88 and .88 for mothers and caregivers, respectively, at T2). For both mothers and caregivers, a composite score for children's attentional control was created by averaging the subscale scores of attention shifting and focusing, r(235) = .29 and r(158) = .43, ps < .01, for mother and caregiver reports, respectively, at T1, and r(218) = .30 and r(141) = .51, ps < .01, for mother and caregiver reports, respectively, at T2.

Toddlers' effortful control also was measured with a snack-delay task (Kochanska et al., 2000, 2001) at both T1 and T2. Children were presented with a placemat that had pictures of hands and were instructed to keep their hands on the placemat. Then, a snack was placed at the top-center of the mat (a goldfish cracker at T1 and M&M candy at T2) and a clear plastic cup was placed over the snack. The toddler was instructed to wait to pick up the cup and eat the snack until the experimenter rang a bell. Practice trials were conducted to ensure that the child understood the task. After the practice trials, four trials were conducted. In these trials, halfway through each delay, the experimenter picked up the bell as if to ring it but did not ring it until the delay time had expired. The delays were 10, 20, 30, and 15 s. Scores ranged from 1 to 9 (1 = child ate the snack right away; 2 = toddler ate the snack after the experimenter lifted the bell; 3 = child touched, but did not eat the snack, in the first half of the trial; 4 = child touched the snack during the second half of the trial; 5 = toddler only touched the cup during the first half; 6 = child touched the cup during the second half of the trial; 7 = child waited the entire trial to eat the snack. Up to two extra points were given if the child kept his or her hands on the mat). Interrater reliabilities (Pearson correlations) were computed on 25% of the sample and were .97 and .99 at T1 and T2, respectively.

Adjustment and social competence

At both T1 and T2, mothers, caregivers, and fathers completed parts of the Infant/Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (Carter et al., 2003). Adults rated each item on a 3-point scale (0 = not true; 2 = very true). The Externalizing scale consisted of two subscales including Activity/Impulsivity (6 items) and Aggression/Defiance (12 items). We also assessed Toddlers' Peer Aggression (6 items) at the T2 assessment but not at T1 because the items were inappropriate for very young children; thus, in order to maintain equivalence of constructs in the longitudinal models, we did not include this subscale in this study. Moreover, because Activity/Impulsivity could overlap with measures of temperament/reactive control, we chose to use only the Aggression/Defiance subscale of the Externalizing scale. We separated the internalizing domain into two subscales, including Separation Distress (6 items) and Inhibition to Novelty (5 items). These two subscales were separated because inhibition to novelty is likely more temperamentally based than separation distress, and we expected these subscales to relate differentially to effortful control (Aksan & Kochanska, 2004). Similar to issues with the Externalizing scale, although we included the Internalizing subscales of General Anxiety (10 items) and Depression/Withdrawal (9 items) at T2, these subscales were not included at T1 because of age appropriateness (Carter et al., 2003). We used only the subscales measured at both times for this study. The Social Competence scale consisted of three subscales including Compliance (8 items), Imitation/Play (6 items), and Empathy (7 items). Reliabilities (αs) for the T1 scales were .75, .74, and .77 for mother, father, and caregiver ratings of externalizing, respectively; .61 and .64 for mother and caregiver ratings of separation distress, respectively (father αs were low and subsequently dropped); .71 and .79 for mother and caregiver reports of inhibition to novelty (father αs were low and subsequently dropped); and .78, .79, and .84 for mother, father, and caregiver ratings of social competence, respectively. For the T2 scales, reliabilities were .75, .72, and .83 for mother, father, and caregiver ratings of externalizing, respectively; .62 and .60 for mother and caregiver ratings of separation distress, respectively; .77 and .83 for mother and caregiver ratings of inhibition to novelty, respectively; and .77, .79, and .80 for mother-, father-, and caregiver-rated social competence, respectively.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Means and standard deviations for the major variables are presented in Table 1. Correlations among the study variables did not differ when we controlled for age at visit.

Table 1.

Unstandardized Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables at Time 1 and Time 2

| Time 1 |

Time 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | M | SD | n | M | SD |

| Maternal supportive | ||||||

| CTNES supportive | 245 | 5.74 | 0.64 | 219 | 5.78 | 0.65 |

| CTNES unsupportive | 245 | 2.74 | 0.84 | 219 | 2.84 | 0.86 |

| Maternal sensitivity | 246 | 3.06 | 0.42 | 216 | 3.30 | 0.36 |

| Maternal warmth | 246 | 3.47 | 0.52 | 216 | 3.50 | 0.47 |

| Effortful control | ||||||

| Mother attentional control | 242 | 4.23 | 0.56 | 223 | 4.58 | 0.56 |

| Caregiver attentional control | 170 | 4.37 | 0.73 | 148 | 4.69 | 0.68 |

| Mother inhibitory control | 240 | 3.56 | 0.86 | 223 | 3.97 | 0.93 |

| Caregiver inhibitory control | 168 | 4.41 | 1.11 | 147 | 4.69 | 0.99 |

| Delay score | 238 | 2.60 | 1.74 | 215 | 6.21 | 2.60 |

| Externalizing problems | ||||||

| Mother externalizing | 239 | 1.50 | 0.27 | 222 | 1.63 | 0.30 |

| Father externalizing | 200 | 1.49 | 0.28 | 154 | 1.57 | 0.28 |

| Caregiver externalizing | 173 | 1.36 | 0.28 | 152 | 1.49 | 0.35 |

| Internalizing problems | ||||||

| Mother separation distress | 237 | 2.01 | 0.37 | 222 | 1.89 | 0.38 |

| Caregiver separation distress | 170 | 1.70 | 0.40 | 150 | 1.65 | 0.37 |

| Mother inhibition to novelty | 239 | 1.85 | 0.43 | 222 | 1.87 | 0.44 |

| Caregiver inhibition to novelty | 171 | 1.76 | 0.50 | 150 | 1.77 | 0.50 |

| Social competence | ||||||

| Mother social competence | 238 | 2.21 | 0.25 | 222 | 2.42 | 0.24 |

| Father social competence | 196 | 2.19 | 0.26 | 161 | 2.42 | 0.25 |

| Caregiver social competence | 164 | 2.16 | 0.30 | 149 | 2.34 | 0.28 |

Note. CTNES = Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale.

Correlations among reports of adjustment/social competence

Correlations among mothers', fathers', and caregivers' reports of adjustment/social competence are presented in Table 2. Significant positive correlations were found between all three reporters' ratings of externalizing problems at T1 and T2, and there was significant within-reporter stability over time. In terms of separation distress, mothers' and caregivers' reports were significantly related to one another at each age, and there was within-reporter stability over time. Mothers' and caregivers' reports of inhibition to novelty were related at both T1 and T2, and there was significant within-reporter stability over time. Finally, mothers', fathers', and caregivers' ratings of social competence were positively related to one another at T1 and T2, and there was significant within-reporter stability in the ratings over time.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Mother, Father, and Caregiver Reports of Competence and Problem Behaviors at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. M EXT T1 | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. M SD T1 | .29** | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. M INH T1 | .05 | .42** | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. M SC T1 | −.07 | −.05 | .15* | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. F EXT T1 | .40** | .00 | −.19** | −.16* | — | |||||||||||||||

| 6. F SC T1 | .05 | .02 | .08 | .48** | −.06 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 7. C EXT T1 | .32** | .07 | −.16* | −.15* | .24** | −.10 | — | |||||||||||||

| 8. C SD T1 | −.01 | .26** | .12 | −.02 | −.01 | −.05 | .26** | — | ||||||||||||

| 9. C INH T1 | −.06 | .21** | .20* | .06 | −.11 | .02 | .14† | .48** | — | |||||||||||

| 10. C SC T1 | −.13 | −.15† | −.10 | .21** | −.12 | .20* | −.23** | −.02 | .05 | — | ||||||||||

| 11. M EXT T2 | .57** | .15* | −.03 | −.03 | .28** | .14† | .28** | .01 | .07 | −.16† | — | |||||||||

| 12. M SD T2 | .33** | .48** | .13† | −.01 | .21** | .04 | .03 | .17* | .09 | −.12 | .33** | — | ||||||||

| 13. M INH T2 | .01 | .31** | .44** | .10 | .02 | .01 | −.06 | .13 | .21* | −.04 | .02 | .42** | — | |||||||

| 14. M SC T2 | −.13† | −.05 | .03 | .58** | −.11 | .22** | −.07 | .00 | .01 | .14† | −.13† | .04 | .09 | — | ||||||

| 15. F EXT T2 | .20* | .10 | −.20* | −.12 | .51** | −.05 | .21* | −.01 | −.13 | −.11 | .36** | .27** | −.01 | −.06 | — | |||||

| 16. F SC T2 | −.11 | −.07 | .08 | .32** | −.15† | .34** | −.19* | −.09 | −.01 | .28** | −.08 | .02 | .06 | .41** | −.26** | — | ||||

| 17. C EXT T2 | .20* | −.01 | −.13 | −.10 | .09 | −.05 | .43** | .23* | .17† | −.11 | .36** | .17† | −.08 | −.02 | .26** | −.05 | — | |||

| 18. C SD T2 | .02 | .21* | .08 | −.06 | .02 | −.06 | .16†* | .41** | .30** | .00 | .02 | .18* | .11 | −.03 | .04 | .02 | .42** | — | ||

| 19. C INH T2 | −.01 | .18* | .22* | −.05 | −.05 | −.07 | .07 | .08 | .50** | −.07 | −.13 | .00 | .32** | .09 | −.24* | −.03 | −.01 | .30** | — | |

| 20. C SC T2 | .01 | .03 | .03 | .22** | −.17† | .20* | −.12 | .07 | −.03 | .38** | −.09 | −.09 | .00 | .17* | −.07 | .22* | −.30** | .01 | .01 | — |

Note. M = mother report; F = father report; C = caregiver report; EXT = externalizing problems; SD = separation distress; INH = inhibition to novelty; SC = social competence.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Correlations among reports of regulation and observed regulation

At T1, mothers' and caregivers' reports of attentional control were positively correlated; however, their reports of inhibitory control were not significantly related. Caregivers' reports of inhibitory control were positively related to toddlers' ability to delay. At T2, mothers' and caregivers' reports of inhibitory control, but not attentional control, were positively related, and toddlers' ability to delay was at least marginally positively related to both mothers' and caregivers' reports of attentional and inhibitory control (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations Between Maternal Socialization Variables and Mother and Caregiver Reports of Effortful Control, and Observed Effortful Control at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. M support T1 | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. M nonsupport T1 | −.24** | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. M sensitivity T1 | .10 | −.40** | — | |||||||||||||||

| 4. M warmth T1 | .09 | −.25** | .45** | — | ||||||||||||||

| 5. M atten T1 | .08 | −.07 | .03 | .01 | — | |||||||||||||

| 6. C atten T1 | .08 | −.12 | .10 | .04 | .26** | — | ||||||||||||

| 7. M inhib con T1 | .01 | −.08 | .09 | .09 | .36** | .12 | — | |||||||||||

| 8. C inhib con T1 | .15† | −.24** | .35** | .24** | .03 | .42** | .06 | — | ||||||||||

| 9. Delay T1 | .14 | −.07 | .14* | −.01 | .11 | .11 | .03 | .26** | — | |||||||||

| 10. M support T2 | .76** | −.30** | .13† | .13† | .12 | .08 | .02 | .11 | .07 | — | ||||||||

| 11. M nonsupport T2 | −.29** | .77** | −.39** | −.27** | −.09 | −.06 | −.05 | −.19* | .01 | −.26** | — | |||||||

| 12. M sensitivity T2 | .14* | −.34** | .55** | .49** | .04 | .03 | .07 | .31** | .03 | .13† | −.37** | — | ||||||

| 13. M warmth T2 | .11 | −.18* | .29** | .50** | −.02 | .03 | .05 | .16* | −.07 | .12† | −.24** | .49** | — | |||||

| 14. M atten T2 | .16* | −.18** | .14* | .09 | .53** | .15† | .27** | .09 | .01 | .17* | −.18** | .09 | .11 | — | ||||

| 15. C atten T2 | .07 | −.16† | .13 | .02 | .10 | .51** | −.01 | .26** | .11 | .08 | −.09 | .12 | .10 | .11 | — | |||

| 16. M inhib con T2 | .02 | −.18** | .26** | .22** | .19** | .12 | .53** | .21** | .00 | −.03 | −.16* | .30** | .22** | .42** | .07 | — | ||

| 17. C inhib con T2 | .19* | −.23** | .29** | .25** | .02 | .26** | .12 | .41** | .04 | .16† | −.25** | .34** | .23** | .15† | .56** | .31** | — | |

| 18. Delay T2 | .11 | −.24** | .32** | .21** | .02 | .14† | .09 | .24** | .03 | .16* | −.13† | .32** | .16* | .12† | .15† | .29** | .28** | — |

Note. M = mother; support = supportive strategies—Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale; nonsupport = nonsupportive strategies—Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale; C = caregiver; atten = attentional control; inhib con = inhibitory control.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Correlations among maternal socialization variables

At both T1 and T2, maternal nonsupportive reaction style was negatively related to observed sensitivity and warmth and to maternal supportive reactions. Observed maternal sensitivity and warmth were positively but nonsignificantly related to reported supportive reactions at both time points. Maternal sensitivity and warmth were positively related to one another at T1 and T2 (see Table 3).

The Relations of Maternal Supportive Parenting and Toddlers' Effortful Control to Toddlers' Adjustment and Social Competence

To determine the relations among the study variables, we first conducted zero-order correlations. Next, because we had multiple indicators for each measure, we conducted measurement models to examine whether latent constructs could be formed. Then, we conducted a series of structural equation models to test mediation for the following: (1) concurrent structural equation models, (2) a longitudinal structural equation model that did not control for stability in the constructs, and (3) longitudinal structural equation models that controlled for the stability in the constructs over time.

Zero-order correlations

Correlations of toddlers' social functioning with mother socialization variables and toddlers' effortful control are presented in Tables 4 and 5. In general, mothers' reported reaction styles were related to mother- and caregiver-reported externalizing problems, mother-reported (and father-reported at T2) social competence, and caregiver-reported separation distress at T1 (correlations varied somewhat for supportive vs. nonsupportive styles). Maternal observed sensitivity and warmth were generally negatively related to externalizing problems and caregivers' reports of separation distress and were positively related to social competence.

Table 4.

Correlations Between Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2) Maternal Socialization Variables, Adult Reports of Effortful Control, Observed Effortful Control, and Toddlers' Adjustment/Social Competence at T1

| Variable | M EXT T1 | M SD T1 | M INHIB T1 | M SC T1 | F EXT T1 | F SC T1 | C EXT T1 | C SD T1 | C INHIB T1 | C SC T1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M support T1 | −.07 | .05 | −.02 | .26** | −.06 | .08 | −.02 | .01 | .12 | .10 |

| M nonsupport T1 | .29** | .05 | .04 | −.12 | .09 | .08 | .21** | .24** | .12 | −.12 |

| M sensitivity T1 | −.17** | −.06 | .04 | .19** | −.09 | .15* | −.32** | −.14† | −.01 | .19* |

| M warmth T1 | −.19** | .00 | .04 | .13† | −.23** | .10 | −.28** | −.18* | −.04 | .04 |

| M atten T1 | −.19** | −.23** | −.13* | .38** | .01 | .14* | −.14† | .00 | −.08 | .11 |

| M inhib cont T1 | −.30** | −.19** | .08 | .34** | −.19** | .24** | −.08 | .10 | .09 | .09 |

| C atten T1 | −.01 | .02 | .01 | .11 | −.04 | .08 | −.27** | −.17* | −.19* | .42** |

| C inhib con T1 | −.17* | −.11 | .16* | .21** | −.15† | .23** | −.54** | −.26** | −.11 | .49** |

| Delay T1 | −.11 | .05 | .06 | .20** | −.09 | .16* | −.25** | −.14 | .02 | .12 |

| M support T2 | −.05 | .06 | −.03 | .20** | −.03 | .00 | .00 | −.01 | −.03 | .07 |

| M nonsupport T2 | .26** | .16* | .06 | −.10 | .06 | .09 | .16† | .22** | .09 | −.10 |

| M sensitivity T2 | −.13† | .01 | .03 | .12 | −.19* | .04 | −.25** | −.17* | −.09 | .10 |

| M warmth T2 | .01 | −.04 | −.02 | .04 | −.09 | −.07 | −.05 | −.13 | −.08 | .04 |

| M atten T2 | −.25** | −.25** | −.01 | .30** | −.12 | .07 | −.04 | −.01 | −.02 | .08 |

| M inhib con T2 | −.28** | −.07 | .14* | .29** | −.21** | .08 | −.20* | .17* | .09 | .22** |

| C atten T2 | .14 | .03 | −.06 | .15† | −.09 | .12 | −.21* | −.13 | −.14 | .21* |

| C inhib con T2 | −.03 | −.04 | .14 | .19* | −.15 | .19* | −.20* | −.10 | .03 | .23* |

| Delay T2 | −.05 | .04 | .17* | .21** | −.08 | .14 | −.08 | −.12 | −.12 | .13 |

Note. M = mother; F = father; C = caregiver; Ext = externalizing problems; SD = separation distress; INHIB = inhibition to novelty; SC = social competence; support = supportive strategies—Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale; nonsupport = nonsupportive strategies—Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale; atten = attentional control; inhib con = inhibitory control.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 5.

Correlations Between Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2) Maternal Socialization Variables, Adult Reports of Effortful Control, Observed Effortful Control, and Toddlers' Adjustment/Social Competence at T2

| Variable | M EXT T2 | M SD T2 | M INHIB T2 | M SC T2 | F EXT T2 | F SC T2 | C EXT T2 | C SD T2 | C INHIB T2 | C SC T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M support T1 | −.08 | −.04 | .03 | .28** | −.12 | .05 | −.09 | .01 | .04 | .10 |

| M nonsupport T1 | .26** | −.01 | −.08 | −.16* | .07 | −.04 | .17* | .04 | −.10 | −.05 |

| M sensitivity T1 | −.17* | −.03 | .14* | .18** | −.17* | .16* | −.28** | −.12 | .11 | .19* |

| M warmth T1 | −.16* | −.03 | −.01 | .19** | −.07 | .03 | −.18* | −.21* | .00 | .12 |

| M atten T1 | −.04 | −.02 | −.04 | .35** | −.07 | .23** | .02 | −.05 | −.11 | .01 |

| M inhib cont T1 | −.22** | −.15* | .11 | .29** | −.17* | .21** | −.04 | −.02 | .20* | .03 |

| C atten T1 | −.09 | −.06 | −.07 | −.04 | .04 | −.06 | −.28** | −.13 | −.05 | .33** |

| C inhib con T1 | −.20* | −.15† | −.02 | .04 | −.10 | .12 | −.46** | −.27** | −.05 | .17† |

| Delay T1 | −.04 | .01 | .06 | .02 | −.13 | .10 | −.13 | .09 | .06 | .06 |

| M support T2 | −.04 | .05 | −.01 | .29** | −.09 | .17* | −.10 | −.01 | .05 | .13 |

| M nonsupport T2 | .25** | .08 | −.01 | −.15* | .11 | .01 | .20* | .10 | −.01 | .00 |

| M sensitivity T2 | −.29** | .01 | .09 | .23** | −.21** | .12 | −.21* | −.17* | .03 | .14 |

| M warmth T2 | −.07 | −.06 | −.04 | .20** | −.14 | .07 | −.12 | −.18* | .03 | .17* |

| M atten con T2 | −.26** | −.27** | −.06 | .43** | −.17* | .10 | −.17* | −.20* | .01 | .06 |

| M inhib con T2 | −.47** | −.16* | .14* | .39** | −.28** | .25** | −.22** | −.10 | .16† | .17* |

| C atten T2 | .01 | −.02 | .10 | .00 | .06 | −.02 | −.44** | −.21* | −.05 | .51** |

| C inhibit con T2 | −.26** | −.14 | .18* | .20* | −.18† | .07 | −.58** | −.22** | .20* | .43** |

| Delay T2 | −.03 | .08 | .16* | .26** | −.10 | .19* | −.18* | −.10 | .11 | .21** |

Note. M = mother; F = father; C = caregiver; Ext = externalizing problems; SD = separation distress; INHIB = inhibition to novelty; SC = social competence; support = supportive strategies—Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale; nonsupport = nonsupportive strategies—Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale; atten = attentional control; inhib con = inhibitory control.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

In terms of the correlations of toddlers' effortful control with social functioning variables, different patterns were found for attentional versus inhibitory control, particularly with regard to internalizing problems. For example, inhibition to novelty sometimes was positively related to higher inhibitory control and was related to lower attentional control within reporters at T1. Thus, we opted to treat these indicators of effortful control separately in structural equation models.

Measurement models

Prior to computing structural models, we tested measurement models through confirmatory factor analyses, which examined whether the manifest variables related to one another in the expected manner. The models contained six latent constructs: maternal supportive parenting, toddlers' effortful control, separation distress, inhibition to novelty, externalizing problems, and social competence. For maternal supportive strategies, mothers' reports of supportive responses to negative emotion, nonsupportive responses to negative emotion, maternal warmth (during puzzle), and maternal sensitivity (combined responses in free play and puzzle) were used as indicators. Because there were distinct relations between the components of effortful control and internalizing problems, we represented effortful control as a composite of parent- and caregiver-rated attentional control (an average of the two ratings), a composite of parent- and caregiver-rated inhibitory control (an average of the two ratings), and the delay-task score. For externalizing and social competence, mothers', fathers', and caregivers' reports were indicators. For separation distress and inhibition to novelty, mothers' and caregivers' reports were indicators. Measurement errors of the study variables were allowed to covary within reporter when indicated by the modification indices. The models were tested using Mplus Version 2.14 (Muthén & Muthén, 2002) because it accounts for incomplete data by using a maximum likelihood estimation method. Model fit was assessed with the chi-square statistic (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). Nonsignificant chi-square statistics, CFIs greater than .90, and RMSEAs less than .08 indicate good model fit, although the chi-square statistic is affected by sample size and thus was not considered the primary indicator of fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 1998).

The measurement model at T1 fit the data well, χ2(94, N = 256) = 131.40, p < .01, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .04 (90% confidence interval [CI] = .02 to .06). All of the model-estimated loadings were significant and in the expected directions (i.e., all positive loadings with the exception of nonsupportive reactions, which negatively loaded on the supportive parenting construct as expected). Similarly, the T2 measurement model fit the data adequately, χ2(98, N = 230) = 166.73, p < .01, CFI = .89, RMSEA = .055 (90% CI = .04 to .07). Again, all of the model-estimated loadings were significant and in the expected directions.

Concurrent models

In the hypothesized model, there were paths from maternal supportive strategies to effortful control and then from effortful control to separation distress, inhibition to novelty, externalizing, and social competence. We also included the direct paths from maternal supportive strategies to the four outcome variables. The latent constructs of separation distress, inhibition to novelty, externalizing, and social competence were correlated. In these models, errors of the indicators from the same reporter were correlated with each other when needed as indicated by the modification indices (Kenny & Kashy, 1992).

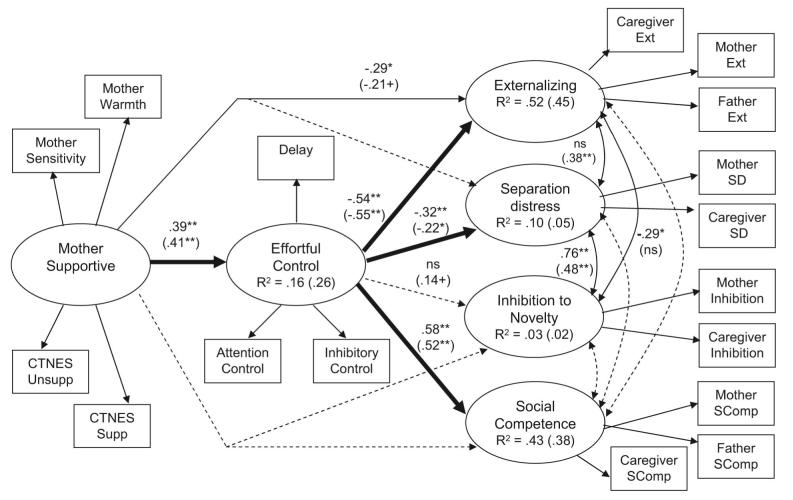

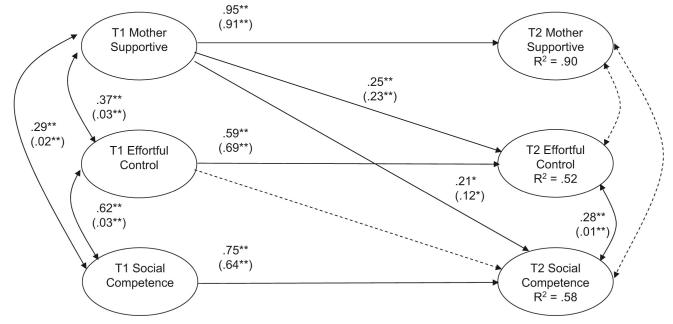

The hypothesized model fit the data well at both T1, χ2(96, N = 256) = 150.62, p < .01, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .03 to .06), and at T2, χ2(94, N = 230) = 137.43, p < .01, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .06 to .06). All of the model-estimated loadings for the indicators were significant (see Table 6 and Figure 1). At both time points, toddlers' effortful control was positively predicted by maternal supportiveness. Effortful control predicted lower externalizing and separation distress and higher social competence. There was a direct effect of maternal supportiveness to low externalizing problems at T1, but this effect was only marginally significant at T2. Inhibition to novelty was not significantly predicted by effortful control or maternal supportiveness at T1, but there was a marginal positive relation between effortful control and inhibition to novelty at T2. Mediated effects were calculated using the procedures outlined by MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, and Sheets (2002). Effortful control significantly mediated the relations between maternal supportive parenting and externalizing, separation distress, and social competence, zs = −2.40 (externalizing), −2.15 (separation distress), and 2.50 (social competence) at T1, and −2.95 (externalizing), −2.10 (separation distress), and 2.70 (social competence) at T2 (see Figure 1). We also calculated the percentage of the total effect (sum of direct and indirect effects) that was mediated; 42%, 93%, and 59% of the effect of mothers' supportive strategies on externalizing, separation distress, and social competence, respectively, was mediated by effortful control at T1 and 51%, 75%, and 53% of the effect of mothers' supportive strategies on externalizing, separation distress, and social competence, respectively, was mediated by effortful control at T2.1

Table 6.

Standardized and Unstandardized Loadings of Study Variables at Time 1 and Time 2 for Concurrent Models

| Time 1 |

Time 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Standardized | Unstandardized | Standardized | Unstandardized |

| Maternal supportive | ||||

| Maternal sensitivity | 0.78 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 1.00 |

| Maternal warmth | 0.58** | 0.92** | 0.57** | 0.88** |

| CTNES supportive | 0.16* | 0.31* | 0.16* | 0.35* |

| CTNES unsupportive | −0.52** | −1.34** | −0.44** | −1.28** |

| Effortful control | ||||

| Inhibitory control composite | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| Attentional control composite | 0.38** | 0.29** | 0.42** | 0.25** |

| Delay score | 0.20* | 0.51* | 0.32** | 0.97** |

| Externalizing problems | ||||

| Mother externalizing | 0.62 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 1.00 |

| Caregiver externalizing | 0.61** | 1.03** | 0.52** | 0.85** |

| Father externalizing | 0.52** | 0.87** | 0.52** | 0.69** |

| Separation distress | ||||

| Mother separation distress | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.00 |

| Caregiver separation distress | 0.33** | 0.40** | 0.30* | 0.33* |

| Inhibition to novelty | ||||

| Mother inhibition to novelty | 0.72 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Caregiver inhibition to novelty | 0.31** | 0.50** | 0.31** | 0.35** |

| Social competence | ||||

| Mother social competence | 0.74 | 1.00 | 0.65 | 1.00 |

| Caregiver social competence | 0.41** | 0.66** | 0.40** | 0.75** |

| Father social competence | 0.59** | 0.82** | 0.56** | 0.90** |

Note. CTNES = Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Cross-sectional models with standardized measurement and parameter estimates. Top numbers represent standardized estimates for Time 1; numbers in parentheses represent standardized estimates for Time 2. CTNES Supp = Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale supportive reactions; CTNES Unsupp = Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale unsupportive reactions; Ext = externalizing problems; SD = separation distress; Inhibition = inhibition to novelty; SComp = social competence. Time 1: χ2(96, N = 256) = 150.62, p < .01, comparative fit index (CFI) = .91, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .05; Time 2: χ2(94, N = 230) = 137.43, p = .01, CFI = .93, RMSEA = .05. Bold lines represent mediated paths. Dashed lines represent nonsignificant paths/correlations. +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Longitudinal model without controlling for stability in the constructs over time

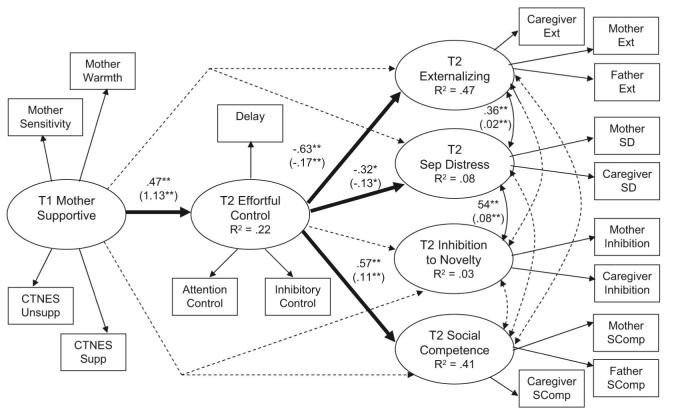

We also constructed a longitudinal extension of the concurrent models to examine mediation over time. In this model, T1 mother supportive behavior predicted T2 effortful control, which in turn predicted T2 adjustment/social competence. We also measured the direct effects of maternal supportive behavior on adjustment/social competence. As with the concurrent data, this hypothesized model fit the data well, χ2(95, N = 258) = 143.65, p < .01, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .05 (90% CI = .03 to .06). The path from maternal supportive strategies to effortful control was positive and significant. All paths from effortful control to adjustment/social competence were significant and in the expected directions with the exception of inhibition to novelty, which could not be predicted by effortful control. Maternal supportive strategies did not directly predict adjustment/social competence. As with the concurrent models, effortful control was a significant mediator of the relations between supportive parenting and socioemotional functioning, zs = −3.23, −2.18, and 2.96 for externalizing, separation distress, and social competence, respectively (see Figure 2). We also calculated the percentage of the total effect; 74%, 65%, and 67% of the effect of mothers' supportive strategies on externalizing, separation distress, and social competence, respectively, was mediated by effortful control.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal model (not controlling stability) with measurement and parameter estimates. Top numbers represent standardized estimates; numbers in parentheses represent unstandardized estimates. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; CTNES Supp = Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale supportive reactions; CTNES Unsupp = Coping With Toddlers' Negative Emotions Scale unsupportive reactions; Sep = separation; Ext = externalizing problems; SD = separation distress; Inhibition = inhibition to novelty; SComp = social competence; χ2(95, N = 258) = 143.65, p < .01, comparative fit index = .92, root-mean-square error of approximation = .05. Bold lines represent mediated paths. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant paths/correlations. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Longitudinal models controlling for stability in the constructs over time

Next, we computed three longitudinal models to test whether mothers' emotion-related parenting and effortful control at T1 predicted children's adjustment/social competence a year later, and whether effortful control at T1 mediated the relations of mother socialization to social functioning over time, above and beyond the autoregressive effects. On the basis of procedures outlined by Cole and Maxwell (2003), we first tested factorial invariance of the model (to test whether the relations of the latent variables to the manifest variables is constant over time). In this test, we compared the longitudinal measurement model (unconstrained model) with a model in which the T1 loadings of the various observed variables were constrained to the same values as their equivalent loadings on the T2 variables (constrained model). This comparison was not significant, Δχ2(11, N = 263) = 11.41, p > .05, indicating that the factor loadings were equal across waves. Thus, for the three longitudinal models, the loadings were set to be equal across time.

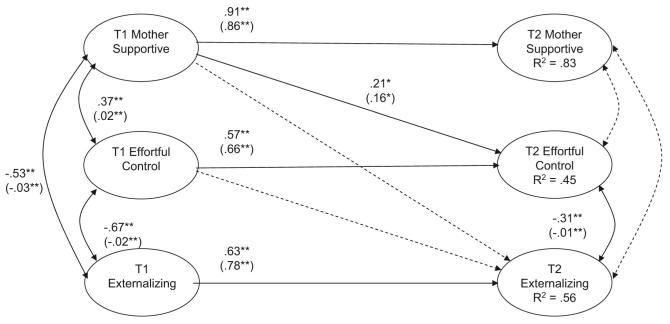

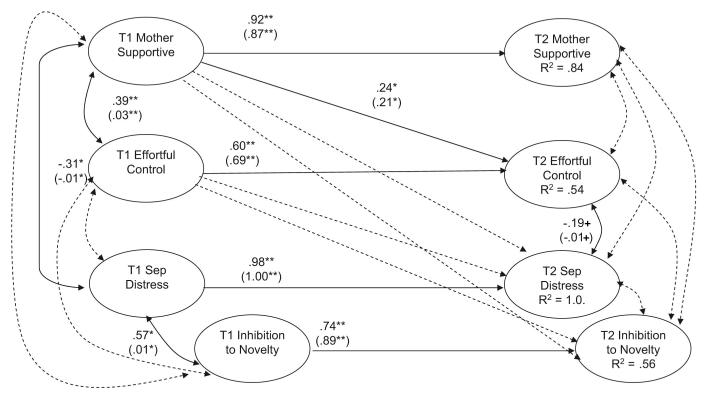

Because this test of mediation would have contained 12 latent constructs (with a relatively small sample size, n = 263, df = 496) if all outcomes were simultaneously included in one model, we separated the outcome measures into three longitudinal mediation models (separation distress and inhibition to novelty were in the same model). In all three models, we included the autoregressive paths (i.e., paths predicting a latent construct from its prior level), paths from maternal supportiveness at T1 to effortful control at T2, and paths from maternal supportive strategies at T1 and effortful control at T1 to adjustment/social competence at T2. The latent constructs were intercorrelated within time. All three models fit the data reasonably well, χ2(157, N = 263) = 203.85, p < .01, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .03 (90% CI = .02 to .05) for externalizing problems; χ2(182, N = 262) = 243.33, p < .01, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .04 (90% CI = .03 to .05) for separation distress/inhibition to novelty; and χ2(153, N = 263) = 212.68, p < .01, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .04 (90% CI = .03 to .05) for social competence. The autoregressive paths for all of the constructs were positive and significant. The path from T1 mother supportive behavior was a significant predictor of higher effortful control at T2 in all three models, even after controlling for stability in the constructs. The paths from T1 effortful control to T2 outcomes were not significant; however, there was a direct positive path from mothers' supportive strategies to social competence (see Figures 3, 4, and 5). In all three models, modification indices did not indicate that any bidirectional paths should be added (from outcomes at T1 to effortful control and mother supportive strategies at T2 and from effortful control at T1 to mother supportive strategies at T2).2

Figure 3.

Externalizing longitudinal panel model with measurement and parameter estimates. Top numbers represent standardized estimates; numbers in parentheses represent unstandardized estimates. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; χ2(157, N = 263) = 203.85, p < .01, comparative fit index = .96, root-mean-square error of approximation = .03. Dashed lines represent nonsignificant paths/correlations. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Figure 4.

Internalizing and inhibition to novelty longitudinal panel model with measurement and parameter estimates. Top numbers represent standardized estimates; numbers in parentheses represent unstandardized estimates. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; Sep = separation; χ2(182, N = 262) = 243.33, p < .01, comparative fit index = .96, root-mean-square error of approximation = .04. Dashed lines represent nonsignificant paths/correlations. + p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Figure 5.

Social competence longitudinal panel model with measurement and parameter estimates. Top numbers represent standardized estimates; numbers in parentheses represent unstandardized estimates. T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; χ2(153, N = 263) = 212.68, p < .01, comparative fit index = .95, root-mean-square error of approximation = .04. Dashed lines represent nonsignificant paths/correlations. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Discussion

The relation of supportive parenting to children's adjustment and social functioning has been well documented, and this study was designed to understand the processes involved in such relations. Overall, the findings provide evidence of the links between early effortful control and toddlers' social functioning and support the notion that the relation between supportive parenting practices and toddlers' developmental outcomes is mediated by toddlers' effortful control (at least within time).

First, the findings from this study demonstrate that effortful control is acquired within the context of the social environment (Gottman et al., 1997). When mothers respond to their toddler's emotions by validating their child's feelings and offering ways to cope with negative emotions, as well as by interacting with their toddlers in warm and child-centered ways, toddlers may learn effective regulation strategies through processes such as modeling and the development of a secure attachment relationship. On the other hand, unsupportive parenting (such as punitive responding to negative emotions) may exacerbate children's negative arousal and may disrupt children's ability to learn effective strategies to cope with their negative arousal. Children with unsupportive mothers are likely to feel overaroused in distressing situations and are unlikely to have developed effective strategies (such as shifting attention or controlling behavior) to cope with this arousal.

In addition, we found a positive link between maternal supportiveness and effortful control over time, even when controlling for earlier levels of maternal behavior and toddlers' effortful control, a finding that is consistent with other work (Kochanska et al., 2000). Thus, the role of socialization practices may be particularly important in toddlerhood because mothers likely serve an essential function in toddlers' regulation because of limited self-regulation capabilities (Kopp, 1989; Spinrad, Stifter, et al., 2004).

These findings also illustrate the potential importance of effortful control to young children's social adjustment and functioning. Specifically, we found that children who were high in effortful control were lower in externalizing problems and separation distress and higher in social competence. Thus, children who can manage their attention and behavior also may have the skills necessary to control their negative emotions, such as anxiety and anger (relevant to externalizing and separation distress) and manage to get along with others and to adhere to social standards. These findings support previous research with older children (Eisenberg, Cumberland, et al., 2001; Kochanska et al., 2001; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003), and it is noteworthy that we included both positive and negative aspects of social functioning in our models.

Central to the goals of this study, we also found evidence for the notion that effortful control mediates the relation between parenting and children's developmental outcomes. This pattern was found at both 18 and 30 months of age. This study adds to existing evidence of the mediational role of effortful control to children's outcomes (Eisenberg, Gershoff, et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2003; Kochanska & Knaack, 2003) and indicates that these relations can be found in very young children.

In addition, there was evidence of a direct effect of maternal support on toddlers' externalizing problems. Toddlers with warm, supportive mothers may be more emotionally secure and therefore less likely to act out and behave aggressively (NICHD Early Childcare Research Network, 2003). It is possible that maternal supportive strategies directly predict externalizing problems in early toddlerhood because effortful control is more rudimentary at this age. In this study, the direct relation between maternal behaviors and externalizing became weaker with age (the effect was marginal at T2). Thus, as children's regulation skills become more sophisticated, the relations between parenting and externalizing problems may become more fully mediated through toddlers' effortful control.

The longitudinal findings also proved to be informative. First, when we computed models that did not control for the stability in constructs over time, we found that effortful control at T2 mediated the relations between maternal supportive strategies at T1 and externalizing problems, separation distress, and social competence. However, using the stronger test of mediation (controlling for prior levels of the constructs; Cole & Maxwell, 2003), early effortful control did not contribute to later adjustment/social competence. These findings should be understood in light of the moderate stability in all of the constructs over the 1-year period. In fact, correlational analyses supported the relations between effortful control and children's later developmental outcomes, albeit some relations were relatively weak. Thus, the unique relations between effortful control and the outcome variables were lost once consistency in the outcomes was taken into account. The implication of these findings is that the relations of maternal supportive parenting, effortful control, and adjustment/social competence may be set in the very early years and that later relations between these variables may be due to these earlier relations between the variables. Alternatively, although effortful control was somewhat stable across our two assessment points, it is still viewed as rather immature in the 2nd year of life. Thus, it is possible that as effortful control becomes more stable and mature, mediation above and beyond the autoregressive effects may be found. Future research should study the impact of effortful control over longer periods of time when the stability of variables is less and in the preschool years when effortful control is more sophisticated.

One strength of this study was that we utilized more pure measures of problem behaviors. In order to examine relations to externalizing problems, we removed subscales of Impulsivity and Activity Level from the Externalizing scale because these sub-scales may reflect temperamental differences more than problematic symptoms. By the same token, we chose to separate the scales used to measure toddlers' internalizing problems because it is likely that inhibition to novelty may reflect temperament more than problem behaviors. Indeed, our findings showed that the relations with effortful control differed for these two constructs: effortful control negatively predicted separation distress but was unrelated to inhibition to novelty in the models. In fact, inspection of the correlational analyses shows that in some cases, at 30 months of age, inhibition to novelty was positively related to inhibitory control and the ability to delay, although it was unrelated to attentional control. Thus, as toddlers develop, those who may be inhibited or overcontrolled may appear relatively behaviorally well-regulated.

These data also provide insight into the measurement of effortful control in young children. We assessed effortful control using mothers' and caregivers' reports and a behavioral measure of regulation (delay). Because the delay task involved a reward, it is thought that it may tap both effortful and reactive control. However, this measure loaded significantly on the effortful control factor, even though most children did not perform well on this task at 18 months of age. This demonstrates that toddlers who are able to control their behavior, at least somewhat, in the context of waiting for something they want are also rated as high in attentional and behavioral control by adults. Prior work has often used a composite of behavioral measures to assess toddlers' effortful control (Kochanska & Knaack, 2003); thus, it is often unclear how the individual measures may perform. The results of our measurement models suggest that the ability to delay (at least at young ages) may be a good measure of effortful control in young children. Other strengths of this study include the use of structural equation modeling, the use of multiple measures and reporters, the use of observational measures of toddlers' effortful control and maternal supportiveness, and the longitudinal design.

A number of limitations of this study should be considered. First, significant attrition occurred from T1 to T2 (33 families who participated at T1 did not remain in the study at T2). Mothers who continued in the study at T2 were more educated, reported higher income, and reported less nonsupportive reactions to toddlers' negative emotions. Despite the fact that our sample at T2 was somewhat biased, it is interesting that the same pattern of findings was demonstrated at both time points. Second, caution should be taken in generalizing these findings to minority children, children in different cultures, or children in poverty. Adult socialization and parenting behaviors may be associated with different outcomes for children of varying cultures or races. Culture plays a crucial role in the socialization of emotion and its developmental outcomes (Cole & Dennis, 1998; Saarni, 1998). For example, in Asian cultures, a high priority is placed on relationships, and the expression of anger is discouraged (Kitayama & Markus, 1995). Thus, Asian parents might display more nonsupportive responses to negative emotions, such as anger, and these strategies may have no adverse consequences for children growing up in Asian societies.

Moreover, this study focused on maternal socialization practices; however, there is evidence that fathers and other socializers (i.e., caregivers, peers) also play an important role in the development of social competence. Fathers likely play a unique role in socializing children's emotions and regulation (Parke & McDowell, 1998). Moreover, fathers not only play a direct role in the development of toddlers' regulation but may also have an indirect function by influencing mothers' parenting strategies or marital satisfaction (Cummings & Davies, 2002). Finally, because our study involved only two time points, we could not use the strongest test of mediation, which requires three time points (Cole & Maxwell, 2003).

Despite its limitations, this study establishes the importance of studying effortful control in very young children when examining children's adjustment and social competence. The findings suggest that maternal supportive parenting and toddlers' effortful regulation relate to the quality of social functioning. The findings from this study are important for intervention work because they suggest that very early parenting can play an important role in toddlers' early ability to regulate attention and behavior and that these skills may set the stage for children's later adjustment and social competence. Interventions should be designed to promote maternal supportive parenting and to teach strategies to parents that will promote toddlers' effortful control. Especially important are parental supportive strategies in response to negative emotions, sensitivity, and warmth. Such parenting practices are likely to help children learn to manage their emotions and behaviors. Moreover, teaching parents to respond to their toddlers supportively should protect toddlers from declines in effortful control and will likely have implications for toddlers' adjustment and maladjustment.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided in part by National Institute of Mental Health Grant 5 R01 MH060838 to Nancy Eisenberg and Tracy L. Spinrad. We express our appreciation to the parents, caregivers, and toddlers who participated in the study and to the many research assistants who contributed to this project.

Footnotes

We also computed a T2 model using the full Infant/Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment Scales (i.e., including peer aggression in the externalizing scale and general anxiety and depression in the internalizing scale). This model also fit the data well, χ2(92, N = 230) = 132.92, p < .01, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .04 (90% CI from .03 to .06), and the model was similar to the model using the reduced scales, with the exception of a nonsignificant negative path from effortful control to internalizing problems, and the direct path from maternal supportive strategies to externalizing problems was nonsignificant. We reported the reduced scale models so that the constructs were consistent over time.

We also attempted to test bidirectional relations by also including paths from toddlers' social functioning at T1 to effortful control and from effortful control at T1 to maternal supportiveness at T2. For the internalizing model, all three additional paths were not significant. For the externalizing and social competence models, adding all three paths resulted in models that would not converge; thus, we attempted to add the paths individually in the externalizing and social competence models. Of all the paths tested, none was significant.

References

- Aksan N, Kochanska G. Links between systems of inhibition from infancy to preschool years. Child Development. 2004;75:1477–1490. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayduk O, Mendoza-Denton R, Mischel W, Downey G, Peake PK, Rodriguez M. Regulating the interpersonal self: Strategic self-regulation for coping with rejection sensitivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:776–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Gill KL, Johnson MC, Smith CL. Emotional reactivity and emotional regulation strategies as predictors of social behavior with peers during toddlerhood. Social Development. 1999;8:310–334. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:467–488. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs Gowan MJ, Jones SM, Little TD. The infant-toddler social and emotional assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:495–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1025449031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Shiner RL. Personality development. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 300–365. [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Dennis TA. Variations on a theme: Culture and the meaning of socialization practices and child competence. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:276–278. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Michel MK, Teti LOD. The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59(23):73–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]