Abstract

In fission yeast, knockout of the calcineurin gene resulted in hypersensitivity to Cl−, and the overexpression of pmp1+ encoding a dual-specificity phosphatase for Pmk1 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) or the knockout of the components of the Pmk1 pathway complemented the Cl− hypersensitivity of calcineurin deletion. Here, we showed that the overexpression of ptc1+ and ptc3+, both encoding type 2C protein phosphatase (PP2C), previously known to inactivate the Wis1–Spc1–Atf1 stress-activated MAPK signaling pathway, suppressed the Cl− hypersensitivity of calcineurin deletion. We also demonstrated that the mRNA levels of these two PP2Cs and pyp2+, another negative regulator of Spc1, are dependent on Pmk1. Notably, the deletion of Atf1, but not that of Spc1, displayed hypersensitivity to the cell wall-damaging agents and also suppressed the Cl− hypersensitivity of calcineurin deletion, both of which are characteristic phenotypes shared by the mutation of the components of the Pmk1 MAPK pathway. Moreover, micafungin treatment induced Pmk1 hyperactivation that resulted in Atf1 hyperphosphorylation. Together, our results suggest that PP2C is involved in a negative feedback loop of the Pmk1 signaling, and results also demonstrate that Atf1 is a key component of the cell integrity signaling downstream of Pmk1 MAPK.

INTRODUCTION

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is one of the most important intracellular signaling that plays a crucial role in cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and cell cycle regulation (Nishida and Gotoh, 1993; Marshall, 1994; Herskowitz, 1995; Levin and Errede, 1995). The multiple MAPK pathways, in response to various extracellular stimuli, regulate eukaryotic gene expression at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels (Sugiura et al., 2003; Edmunds and Mahadevan, 2004). The MAPKs mediate their effects through phosphorylation and hence the activation/inactivation of a range of substrates, including transcription factors and downstream signaling proteins.

We have been studying the Pmk1 MAPK signaling pathway in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. The Pmk1 MAPK, a homologue of the mammalian extracellular signal-regulated kinase/MAPK regulates cell morphology and cell integrity in fission yeast (Toda et al., 1996; Zaitsevskaya-Carter and Cooper, 1997). The Pmk1 MAPK is highly similar to the budding yeast Mpk1/Slt2, which also plays a central role in cell integrity signaling (Levin, 2005) by phosphorylating and activating the Rlm1 transcription factor in response to cell wall stress (Jung and Levin, 1999; Jung et al., 2002). The Pmk1 MAPK pathway comprises the Pmk1 MAPK, Pek1 MAPK kinase (MAPKK) (Sugiura et al., 1999), and the Mkh1 MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK) (Sengar et al., 1997). Pck2, a protein kinase C homologue in fission yeast (Toda et al., 1993), interacts with Mkh1 MAPKKK and thereby Pck2 activates and acts upstream of the Pmk1 signaling pathway (Ma et al., 2006).

We have previously demonstrated that the knockout of the fission yeast calcineurin gene ppb1+ or the inhibition of calcineurin activity by immunosuppressants results in the hypersensitivity to Cl− and that calcineurin and Pmk1 MAPK play antagonistic roles in Cl− homeostasis (Sugiura et al., 1998, 2002). This genetic interaction between calcineurin and Pmk1 MAPK was used to screen for multicopy suppressors of the Cl−-hypersensitive phenotype of the calcineurin knockout, and we identified several genes, namely, pmp1+ encoding a dual-specificity MAPK phosphatase (Sugiura et al., 1998), pek1+ encoding a MAPKK (Sugiura et al., 1999), and rnc1+ encoding a novel KH-type RNA-binding protein that binds and stabilizes Pmp1 mRNA (Sugiura et al., 2003, 2004). Notably, these genes negatively regulate the Pmk1 MAPK signaling. This genetic interaction was further developed to screen for viable in the presence of immunosuppressant and chloride ion (vic) mutants. Most recently, we have identified novel components of the Pmk1 MAPK pathway through the isolation of vic mutants. This includes the vic1-1/cpp1-v1 mutation in the cpp1+ gene encoding a β subunit of the protein farnesyltransferase (Ma et al., 2006). Also, we demonstrated that the small GTPase Rho2 is a novel target of the farnesyltransferase Cpp1 and that Cpp1 and Rho2 act upstream of the Pck2–Pmk1 MAPK cell integrity signaling pathway (Ma et al., 2006). Thus, the genetic screen based on the functional interaction between calcineurin and Pmk1 MAPK has efficiently isolated both positive and negative regulators of the Pmk1 MAPK pathway.

To further understand the regulation of the cell integrity signaling, we have thus far identified several components of the Pmk1 MAPK pathway. However, the downstream transcription factor(s) mediating the cell integrity signaling in fission yeast remains unknown.

In yeasts and mammals, the protein serine/threonine phosphatase type 2C (PP2C) has been suggested to negatively regulate stress signals transmitted by the stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) pathways. These SAPKs include Hog1 in budding yeast, Spc1 (also known as Sty1 or Phh1) in fission yeast, and p38 in mammals (Maeda et al., 1994; Shiozaki et al., 1994; Shiozaki and Russell, 1995; Takekawa et al., 1998; Nguyen and Shiozaki, 1999).

Here, we show that the two PP2Cs, namely, Ptc1 and Ptc3, act as high-dosage suppressors of calcineurin deletion. Also, we demonstrated that Ptc1 and Ptc3 play a role in the negative regulation of the Pmk1 signaling and that Pmk1 regulates these PP2Cs at the transcriptional level through Atf1, a transcription factor downstream of the Spc1 stress-activated MAPK pathway (Shiozaki and Russell, 1996; Wilkinson et al., 1996; Gaits et al., 1998). Most importantly, Pmk1 phosphorylates Atf1 upon cell wall damage, thereby posing Atf1 as a downstream target of the Pmk1 cell integrity MAPK pathway. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a cross-talk between two MAPK signaling pathways through the regulation of the Atf1 transcription factor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and Genetic and Molecular Biology Methods

S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The complete medium yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) and the minimal medium Edinburgh minimal medium (EMM) have been described previously (Toda et al., 1996). Standard genetic and recombinant DNA methods (Moreno et al., 1991) were used except where noted. FK506 was provided by Fujisawa Pharmaceutical (Osaka, Japan).

Table 1.

Schizosaccharomyces pombe strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| HM123 | h− leu1-32 | Our stock |

| HM528 | h+ his2 | Our stock |

| KP928 | h+ his2 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | Our stock |

| KP119 | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ppb1::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP133 | h− leu1-32 ura4 pap1::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP208 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 pmk1::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP226 | h− leu1-32 his1-102 wis1::his1+ | Our stock |

| KP250 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 pmp1::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP257 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 isp6::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP264 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 pmp1::ura4+ pmk1::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP330 | h−leu1-32 pck2::LEU2 | Our stock |

| KP471 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 spc1::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP495 | h− leu1 ura4-D18 atf1::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP590 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M216 ctt1::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP649 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ptc2::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP650 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ptc3::ura4+ | Our stock |

| KP898 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 its8-1 | Our stock |

| KP898 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ptc1::ura4+ | This study |

| KP907 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ptc1::ura4+ ptc3::ura4+ pmk1::ura4+ | This study |

| KP909 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ptc1::ura4+ ptc3::ura4+ | This study |

| KP1378 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 mbx2::ura4+ | This study |

| SP213 (FY14017) | h90 leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 chs1::ura4+ | Matsuo et al. (2004) |

| SP214 (FY14018) | h+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 ade6-M210 chs2::LEU2 | Matsuo et al. (2004) |

| SP510 | h+ leu1-32 ade4 tps1 | Our stock |

| SP556 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 pmk1-GST-KanMx6 | This study |

| SP562 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ptc1::LEU2 pmk1-GST-KanMx6 | This study |

| SP564 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ptc1::LEU2 pmk1-GST-KanMx6 | This study |

| SP566 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ptc3::ura4+ pmk1-GST-KanMx6 | This study |

| SP576 | h− leu1-32 ura4-D18 ptc2::ura4+pmk1-GST-KanMx6 | This study |

The S. pombe strains constructed in this study are deposited at the YGRC/NBRP.

Cloning and Knockout of the ptc3+ Gene

To clone the ptc3+ gene, the Cl− sensitivity of Δppb1 mutants (KP119) was used (Yoshida et al., 1994). The Δppb1 mutants were grown at 30°C and were transformed with an S. pombe genomic DNA library constructed in the vector pDB248 (Beach et al., 1982). The Leu+ transformants were replica-plated onto YPD plates containing 0.12 M MgCl2 and the plasmid DNA was recovered from transformants that showed a plasmid-dependent rescue. By DNA sequencing, the suppressing plasmids were identified to contain the ptc3+ gene (SPAC2G11.07c).

To knockout the ptc1+ gene, a one-step gene disruption by homologous recombination was performed (Rothstein, 1983). The ptc1::ura4+ disruption was constructed as follows. The EcoRI–HindIII fragment containing the ptc1+ gene was subcloned into the EcoRI–HindIII site of pUC19. Then, a BamHI fragment containing the ura4+ gene was inserted into the BamHI site of the previous construct. The fragment containing the disrupted ptc1+ gene was transformed into haploid cells. Stable integrants were selected on medium lacking uracil, and knockout of the gene was checked by genomic Southern hybridization and tetrad analysis (data not shown).

Cloning and Knockout of the mbx2+ Gene

The mbx2+ gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the genomic DNA of S. pombe as a template. The sense primer used for PCR was 5′-CGC GGA TCC ATG GGG CGC AAA AAA ATC TCC ATT GC-3′ (BamHI site and start codon are underlined), and the antisense primer was 5′-CGC GGA TCC TTA GTA TTT GAC ATC ACT GAG TGA ATG-3′ (BamHI site and stop codon are underlined). The amplified product was digested with BamHI, and the resulting fragment was subcloned into Bluescript SK(+) to create pBS-mbx2.

To knockout the mbx2+ gene, a one-step gene disruption by homologous recombination was performed as described previously (Rothstein, 1983). The mbx2::ura4+ disruption was constructed as follows. The PCR-amplified fragment containing the open reading frame of the mbx2+ gene in the Bluescript vector (pBS-mbx2) was digested with PvuI and XcmI, and blunt-ended, and then ligated to a SmaI fragment containing the ura4+ gene, causing the interruption of the open reading frame. The fragment containing the disrupted mbx2+ gene was transformed into diploid cells. Stable integrants were selected on medium lacking uracil, and disruption of the gene was checked by genomic Southern hybridization (data not shown).

Construction of C-terminally Tagged Pmk1 Strains

A PCR-based gene targeting method (Bähler et al., 1998) was used for constructing the C-terminally glutathione transferase (GST)-tagged Pmk1 strain under the regulation of the endogenous pmk1 promoter. The tagged Pmk1 strain used in this study behaved like the nontagged parental strains, indicating that tagging does not interfere with protein function.

Northern Blot Analyses

Total RNA was isolated by the method of Kohrer and Domdey, (1991). A 20-μg sample of total RNA/lane was subjected to electrophoresis on denaturing formaldehyde 1% agarose gels and transferred to nylon membranes. Hybridization was performed using digoxygenin (DIG)-labeled antisense cRNA probes coding for Ptc1, Ptc3, Pyp2, Its8, and Leu1 as described previously (Hirayama et al., 2003). The DIG-labeled hybrids were detected by an enzyme-linked immunoassay by using an anti-DIG–alkaline phosphatase antibody conjugate. The hybrids were visualized by chemiluminescence detection on a light-sensitive film according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

In vitro kinase reactions were performed as described previously (Sugiura et al., 1999) with some modifications. GST-Pmk1 in place of Pmk1-hemagglutinin was used as an enzyme, and Atf1-FLAG purified from fission yeast in place of the myelin basic protein was used as a substrate.

Miscellaneous Methods

Cell extract preparation and immunoblot analysis were performed as described previously (Sio et al., 2005).

RESULTS

Isolation of the ptc3+ Gene as a Multicopy Suppressor of Calcineurin Knockout

We have previously demonstrated that calcineurin and Pmk1 MAPK play antagonistic roles in Cl− homeostasis (Sugiura et al., 1998). Consistently, our genetic screen for the high-dosage suppressors of the Cl−-hypersensitive phenotype of calcineurin knockout has efficiently isolated negative regulators of the Pmk1 signaling, including pmp1+, a dual-specificity phosphatase for Pmk1 (Sugiura et al., 1998).

To identify novel players other than pmp1+, pek1+, and rnc1+ (Sugiura et al., 1999; Sugiura et al., 2003) that are involved in the inhibition of the Pmk1/Pck2 signaling, we screened for genes that when overexpressed can suppress the Cl− hypersensitivity of calcineurin deletion. Here, we focus on the ptc3+ gene.

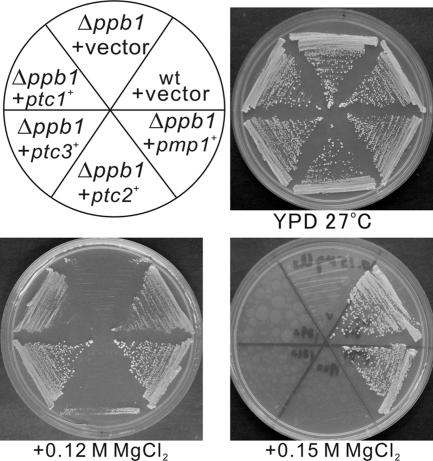

As shown in Figure 1, Δppb1 (calcineurin knockout) cells grew well in rich YPD medium. In the presence of 0.12 M MgCl2, the Δppb1 cells failed to grow, whereas wild-type cells grew well. However, when the ptc3+ gene was overexpressed, the calcineurin deletion cells grew in the presence of 0.12 M MgCl2 (Figure 1, +ptc3+ +0.12 M MgCl2). The ptc3+ encodes a member of the PP2C that is highly similar to the budding yeast PTC3 and human isoforms of PP2C. In fission yeast, the genes that encode PP2C are ptc1+, ptc2+, ptc3+, ptc4+, and azr1+. Notably, recent studies revealed that ptc1+, ptc2+, and ptc3+ are implicated in the negative regulation of the stress-activated Wis1–Spc1–Atf1 MAPK signaling, whereas ptc4+ is reported to play a role in vacuole fusion (Gaits and Russell, 1999), and azr1+ plays a role in 5-azacytidine sensitivity (Platt and Price, 1997). Thus, our genetic screen for the negative regulators of the Pmk1 signaling has isolated an important player of the SAPK signaling in fission yeast.

Figure 1.

Overproduction of type 2C phosphatase genes suppressed the Cl−-hypersensitivity caused by calcineurin knockout (Δppb1). The Δppb1 cells transformed with each of the multicopy plasmids carrying pmp1+, ptc1+, ptc2+, ptc3+, or with the control vector pDB248, or wild-type cells harboring the control vector were streaked onto the plates as indicated, and they were incubated for 3 d at 33°C.

We then examined whether the overexpression of genes encoding other PP2Cs involved in the inactivation of the Spc1 signaling, namely, ptc1+ and ptc2+ can also suppress the sensitivity of calcineurin deletion. As shown in Figure 1, the overexpression of ptc1+ clearly suppressed calcineurin deletion, because Δppb1 cells overexpressing ptc1+ grew in the presence of 0.12 M MgCl2 (Figure 1, +ptc1+, +0.12 M MgCl2). In contrast, the overexpression of ptc2+ failed to suppress calcineurin deletion (Figure 1, +ptc2+, +0.12 M MgCl2). Notably, the suppression ability of Pmp1 was stronger compared with that of Ptc1 or Ptc3, because Δppb1 cells overexpressing pmp1+, but not ptc1+ or ptc3+, grew in the presence of 0.15 M MgCl2 (Figure 1, +0.15 M MgCl2).

PP2C Is Involved in the Negative Regulation of the Pmk1 Pathway

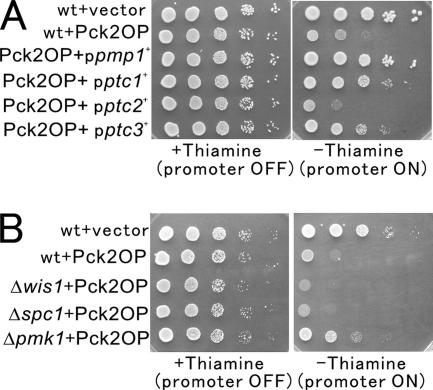

The above-mentioned results indicate that Ptc1 and Ptc3, the two negative regulators of the Spc1 pathway, act as high-dosage suppressors of calcineurin deletion, and the results suggest the possibility that these PP2Cs are also involved in the regulation of the Pmk1 signaling. To test whether Ptc1 and Ptc3 play a role in the inactivation of the Pck/Pmk1 pathway, we used the toxicity caused by the overproduction of Pck2, an upstream component of the Pmk1 MAPK. Our previous report demonstrated that the overproduction of Pck2 hyperactivated Pmk1, resulting in the toxicity as seen in wild-type cells, but not in the knockout cells of the component of the downstream Pmk1 MAPK, i.e., Δmkh1, Δpek1, or Δpmk1 (Figure 2B, Δpmk1) (Ma et al., 2006). Consistently, the overexpression of Pmp1 phosphatase for Pmk1 clearly suppressed the toxicity caused by Pck2 overproduction, and the suppression was achieved as efficiently as that of Pmk1 deletion through the inhibitory effect on Pmk1 signaling (Figure 2A, +ppmp1+).

Figure 2.

Suppression by PP2C is independent of the Spc1 MAPK pathway. (A) Overexpression of pmp1+, and ptc1+ or ptc3+, suppressed the growth defect due to the overproduction of Pck2. Wild-type cells containing pREP1-GFP-Pck2 (Pck2 OP) and either the multicopy plasmid carrying pmp1+, ptc1+, ptc2+, ptc3+, or the control vector, were grown in EMM containing 4 μM thiamine. Cells as indicated were spotted onto the plates, and they were incubated with or without 4 μM thiamine for 4 d at 27°C. (B) Overproduction of Pck2 is toxic to wild-type cells, Δwis1, or Δspc1 cells, but not to Δpmk1 cells. The cells as indicated harboring pREP1-GFP-Pck2 were spotted onto the plates, and then they were incubated as described in Figure 2A.

We then examined the effects of the overexpression of PP2Cs on the toxicity of Pck2 overproduction. Expectedly, the overexpression of ptc1+ and ptc3+, but not that of ptc2+, alleviated the toxicity of Pck2 overproduction (Figure 2A). Again, the suppression by Pmp1 was stronger than that by Ptc1 or Ptc3 (Figure 2A), and the result correlates well with the suppression of the Cl− hypersensitivity in Δppb1 cells by these phosphatases as shown in Figure 1.

Because Ptc3 and Ptc1 have been reported to inhibit the Spc1 pathway, we examined the toxicity caused by Pck2 overproduction in the knockout strains of the components of the Spc1 MAPK pathway. The results clearly showed that Pck2 overproduction caused severe toxicity in Δwis1 cells wherein the MAPKK for the Spc1 MAPK was deleted, or in Δspc1 cells, similar to that observed in wild-type cells but in clear contrast to the Δpmk1 cells (Figure 2B). Thus, the suppression of calcineurin deletion or the suppression of the toxicity of Pck2 overproduction by Ptc3 or Ptc1 is not achieved through the inhibition of the Spc1 MAPK signaling.

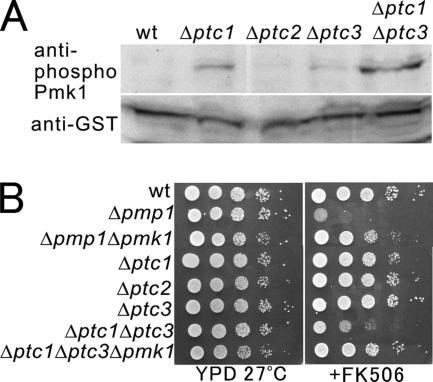

To examine whether these PP2Cs are involved in the regulation of the Pmk1 pathway, the levels of Pmk1 phosphorylation were monitored in wild-type cells and in the series of knockout mutants of these phosphatases, each expressing Pmk1-GST from its chromosomal locus under the regulation of the endogenous pmk1 promoter, by using anti-phospho Pmk1 antibodies. As shown in Figure 3A, the Δptc1 mutants exhibited a significant increase in phosphorylation of Pmk1 compared with that of wild-type cells, whereas no phosphorylation was detected. In the Δptc3 mutant cells, the level of Pmk1 phosphorylation was slightly increased (Figure 3A). Notably, the Δptc1Δptc3 double mutants displayed a markedly increased phosphorylation of the Pmk1 as compared with that of wild-type cells (Figure 3A), suggesting that Ptc1 and Ptc3 are cooperatively involved in the negative regulation of the Pmk1 MAPK signaling, with a greater contribution of Ptc1 relative to Ptc3.

Figure 3.

PP2Cs negatively regulate the phosphorylation of Pmk1 in vivo. (A) Wild-type cells, Δptc1, Δptc2, Δptc3, or Δptc1Δptc3 cells, each carrying a chromosomal version of pmk1::GST were grown in EMM. Immunoblotting using anti-phospho Pmk1 and anti-GST antibodies showed that Pmk1 is hyperphosphorylated in the Δptc1Δptc3 cells. (B) The cells as indicated were spotted onto the plates, and they were incubated as described in Figure 2A.

If Ptc1 and Ptc3 are involved in Pmk1 inactivation, then PP2C deletion strains should show phenotypes similar to that of the Pmp1 deletion strain. We then compared the phenotypes of the deletion strains of these type 2C phosphatases with that of the Pmp1 deletion strain. None of the single-deletion mutants of PP2Cs exhibited a significant sensitivity to the immunosuppressant drug FK506, whereas Δpmp1 mutant cells displayed a severe sensitivity to the drug (Figure 3B, Δpmp1, +FK506). However, the growth of the Δptc1Δptc3 double mutant was significantly inhibited in the presence of FK506 (Figure 3B Δptc1Δptc3, +FK506). Notably, the immunosuppressant sensitivity of the Δptc1Δptc3 mutant cells and that of Δpmp1 cells was suppressed by Pmk1 deletion, because the triple mutants Δptc1Δptc3Δpmk1 cells and the double mutants Δpmp1Δpmk1 cells grew in the presence of FK506 (Figure 3B, +FK506). These results suggest that the growth defect of the Δptc1Δptc3 mutants and the Δpmp1 mutants in the presence of FK506 was due to the hyperactivation of the Pmk1 signaling, and this is in good correlation with the phosphorylation pattern as shown in Figure 3A.

The Pmk1 MAPK Pathway Up-Regulates the Expression of PP2Cs

The activation of MAPK pathway often leads to an increase in the transcript level of the protein phosphatases that inactivate the pathway. As shown previously, the transcript level of PP2Cs was up-regulated in response to stress conditions, including a high-osmolarity stimulation, so we tested whether the Pmk1 MAPK pathway up-regulates the expression of PP2Cs by examining the levels of PP2C transcripts in Δpmk1 cells compared with those of wild-type cells.

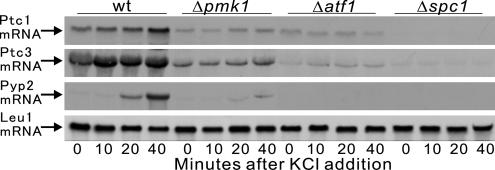

In Figure 4, the Ptc1 mRNA expression was significantly induced in wild-type cells after the addition of 1 M KCl to the growth medium. In contrast, in Δpmk1 mutant cells, the basal level of Ptc1 expression was significantly reduced and the induction of Ptc1 mRNA by KCl treatment was greatly impaired, indicating that the expression of Ptc1 is in part dependent on the Pmk1 signaling (Figure 4, Ptc1).

Figure 4.

Pmk1 up-regulates the mRNA levels of PP2Cs and Pyp2. Induction of Ptc1, Ptc3, and Pyp2 mRNA by osmotic stress requires Pmk1 activity. Wild-type cells, Pmk1-null cells, Atf1-null cells, or Spc1-null cells were incubated in YPD medium at 27°C with 1 M KCl for 0, 10, 20, or 40 min. Total RNA (20 μg) was subjected to Northern analysis by using a DIG-labeled Ptc1, Ptc3, Pyp2, or Leu1 cRNA.

We next examined whether ptc3+ mRNA was regulated by Pmk1. Northern blot analysis demonstrated that in unstressed conditions the level of ptc3+ mRNA was reduced significantly in Δpmk1 cells compared with that of wild-type cells (Figure 4, Ptc3, 0 min). A significant increase in the amount of ptc3+ mRNA was observed when wild-type cells were under stress with the addition of 1.0 M KCl, whereas almost no increase in the amount of ptc3+ mRNA was observed in Δpmk1 cells (Figure 4, Ptc3). Thus, the basal expression and the osmotic stress-induced expression of Ptc1 and Ptc3 are dependent on Pmk1, consistent with the notion that these PP2Cs are involved in the negative regulation of the Pmk1 signaling.

We further examined whether Pyp2, another negative regulator of the stress-sensing Spc1 MAPK pathway, is also dependent on the Pmk1 signaling. Notably, Pyp2 mRNA was clearly induced upon high-osmolarity stimulation in wild-type cells, and the induction was markedly reduced in Δpmk1 cells, indicating that Pmk1 also up-regulates Pyp2 mRNA levels (Figure 4, Pyp2). The expression levels of PP2Cs and Pyp2 were transcriptionally regulated by the Atf1 transcription factor that acts downstream of the Spc1 MAPK (Shiozaki and Russell, 1996; Degols and Russell, 1997). Consistent with these reports, the transcripts of Ptc1, Ptc3 and Pyp2 are clearly dependent on Atf1, because the induction of these phosphatases upon high-osmolarity stimulation was almost abolished in the Δatf1 cells (Figure 4, Δatf1). We also displayed the same transcription data for Spc1 deletion, and the data revealed that all these transcripts were barely detectable in Spc1 deletion, consistent with the previous reports (Figure 4, Δspc1).

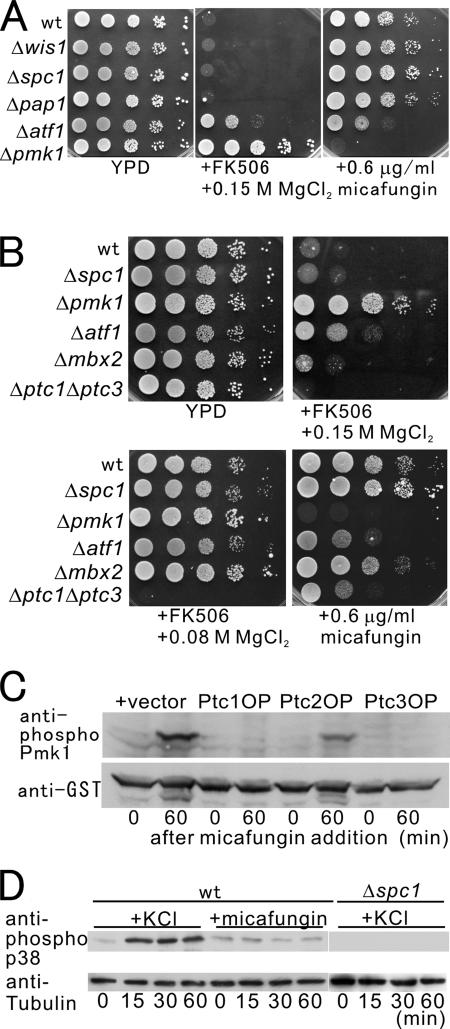

Atf1 Is Involved in Cell Integrity Signaling

The above-mentioned findings have led us to raise the hypothesis that Pmk1 MAPK and Spc1 MAPK signaling pathways might converge at the Atf1 transcription factor, and that Pmk1 might control the expression of these phosphatases through the regulation of Atf1. As a first step to test this possibility, we examined the phenotypes of the Δatf1 cells compared with those of the Δpmk1 cells and the deletion strains of the components of the Wis1–Spc1 MAPK pathway. As already shown, the inhibition of the Pmk1 MAPK pathway specifically suppressed the Cl− hypersensitivity caused by calcineurin deletion or the inhibition of calcineurin activity upon FK506 treatment. Notably, both the Δatf1 cells and Δpmk1 cells, but not the Δwis1 cells or Δspc1 cells, grew in the presence of the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 and 0.15 M MgCl2 (Figure 5A +FK506 + 0.15 M MgCl2). Moreover, Δpap1 cells, the deletion mutants of another transcription factor of which oxidation and localization is affected by the Spc1 MAPK failed to grow in the same medium (Figure 5A, Δpap1, +FK506 + 0.15 M MgCl2). This indicated that Δatf1 cells specifically displayed the vic phenotype that is the characteristic phenotype shared by the mutations in the components of the Pmk1 MAPK pathway. However, it should be noted that the growth of Δatf1 cells in the presence of FK506 + 0.15 M MgCl2 was intermediate relative to the other mutants, i.e., Δatf1 cells grew clearly better than wild-type cells or the deletion strains of the components of the Wis1–Spc1 MAPK pathway, but Δatf1 cells grew slowly compared with Δpmk1 cells.

Figure 5.

Atf1 is involved in Pmk1 MAPK-mediated cell integrity signaling. (A) Knockout of the atf1+ and pmk1+ genes displayed vic phenotype and micafungin sensitivity. The cells as indicated were spotted onto the plates, and then they were incubated for 4 d at 27°C. It should be noted that the sensitivity of the Δatf1 cells is intermediate for both treatments. (B) Knockout of the mbx2+ gene showed a modest cell integrity phenotype. The cells as indicated were spotted onto the plates and then were incubated for 4 d at 27°C. (C) Micafungin treatment stimulated phosphorylation of Pmk1 MAPK. Wild-type cells carrying a chromosomal version of pmk1::GST, transformed with either the multicopy plasmid carrying ptc1+, ptc2+, ptc3+, or the control vector, were grown to mid-log phase in EMM, and then they were incubated in the same medium containing 1.0 μg/ml micafungin for the time interval as indicated, and cells were collected and lysed at each time point. Immunoblotting was performed as described in Figure 3A. (D) KCl but not micafungin treatment induced hyperphosphorylation of Spc1 MAPK. Wild-type cells and Δspc1 cells were prepared as described in Figure 5C, and cells were incubated in the same medium containing 1.0 μg/ml micafungin or 1.0 M KCl for the time interval as indicated, and they were lysed at each point. Immunoblotting using anti-phospho p38 and anti-tubulin antibodies showed that Spc1 is hyperphosphorylated in response to osmotic stress but not to micafungin treatment. In Δspc1 strain, no signal was detected upon KCl treatment, indicating that the signals detected by anti-phospho-p38 antibodies are indeed derived from the Spc1 MAPK.

Another indication of a defect in the protein kinase C-Pmk1 MAPK signaling pathway is a hypersensitivity to the cell wall-damaging agent micafungin, so we next examined whether Δatf1 cells are hypersensitive to micafungin. Expectedly, Δatf1 cells displayed a significant growth defect in the presence of 0.6 μg/ml micafungin, whereas wild-type cells grew normally (Figure 5A, +0.6 μg/ml micafungin). Also, the sensitivity of the Δatf1 cells was weaker compared with that of the Pmk1 deletion cells (Figure 5A, +0.6 μg/ml micafungin). In clear contrast, the growth of the Δwis1 cells, the Δspc1 cells or the Δpap1 cells was not altered at all by the drug (Figure 5A). Again, the sensitivity of Δatf1 cells was intermediate i.e., the growth of the Δatf1 cells was moderately inhibited in the media containing 0.6 μg/ml micafungin, whereas the growth of Δpmk1 cells was severely inhibited in the same media. We also examined the sensitivity of these strains to the cell wall-degrading enzyme zymolyase, and Δatf1 and Δpmk1 cells, but not Δwis1, Δspc1 and Δpap1 cells, displayed the hypersensitivity to the enzyme (data not shown). Together, these results suggest the possibility that Atf1 is involved in the cell wall integrity signaling regulated by Pmk1.

The finding that the Δatf1 cells displayed an intermediate response in terms of its sensitivity for both treatments has prompted us to examine whether another target of Pmk1 that regulates cell integrity might exist. In budding yeast, Rlm1 was reported to be a key transcription factor that acts downstream of Slt2/Mpk1 MAPK regulating the cell wall integrity signaling. (Jung and Levin, 1999; Jung et al., 2002). Therefore, we deleted the mbx2+ gene, encoding a MADS box-type transcription factor that is highly similar to Rlm1 in budding yeast (Buck et al., 2004), and we examined the phenotypes of Δmbx2 cells and compared them with those of other mutants. The Δmbx2 cells slightly grew in the presence of FK506 + 0.15 M MgCl2, whereas wild-type cells failed to grow (Figure 5B, +FK506 + 0.15 M MgCl2). However, it should be noted that the growth of Δmbx2 cells was clearly poorer compared with that of Δatf1 cells in the same media (Figure 5B, +FK506 + 0.15 M MgCl2). Also, the growth of Δmbx2 cells was only modestly inhibited in the presence of 0.6 μg/ml micafungin (Figure 5B, +0.6 μg/ml micafungin). Thus, unlike Rlm1 in budding yeast, Mbx2 seems to play only a minor role in cell wall integrity signaling. These results, together with the previous results on the sensitivity of the Δatf1 cells to cell wall-damaging agents suggests that Atf1, which showed a greater contribution compared with Mbx2, an Rlm1 homologue in fission yeast, seems to play a key role in the cell wall integrity signaling.

It is of interest to investigate the phenotypes of the deletion of the negative regulators of the cell integrity Pmk1 MAPK signaling. We, therefore, examined the phenotypes of the Δptc1Δptc3 double knockout mutant cells, and we compared them with those of other mutants. As shown in Figure 5B, Δptc1Δptc3 cells failed to grow in the presence of FK506 + 0.15 M MgCl2. Moreover, the Δptc1Δptc3 failed to grow in the media containing FK506 + 0.08 M MgCl2, wherein wild-type cells and all other mutant cells grew well, indicating that the deletion of the negative regulators of the Pmk1 signaling exacerbated the phenotypes of calcineurin inhibition by FK506 (Figure 5B, +FK506 + 0.08 M MgCl2). These results are consistent with the results shown in Figure 3A, showing that Pmk1 is hyperphosphorylated in Δptc1Δptc3 cells, and these results are also consistent with our previous reports that the overexpression of Pek1DD, a constitutively active version of Pek1 MAPKK for Pmk1, induced the hyperphosphorylation of Pmk1 and exacerbated the Cl−-sensitive growth defect of calcineurin knockout. It should be noted that the Δptc1Δptc3 cells displayed a moderate but significant growth defect in the media containing 0.6 μg/ml micafungin, similar to that of Δatf1 cells (Figure 5B, +0.6 μg/ml micafungin). This raises the possibility that both the inactivation and the hyperactivation of Pmk1 MAPK might result in the imbalance of cell wall integrity signaling, leading to the hypersensitivity to the cell wall-damaging agent micafungin.

Cell Wall Stress Activates Pmk1 MAPK Signaling

The distinct phenotypes of the Δatf1 cells, as differed from those of Spc1 MAPK deletion, with respect to the sensitivity of the cell wall-damaging agents suggested that the cell integrity signal is specifically transmitted through Pmk1 MAPK, but not through Spc1 MAPK. To test this possibility, we examined the effect of micafungin treatment on the phosphorylation levels of Pmk1 and Spc1. Expectedly, the phosphorylation of Pmk1 was markedly induced upon micafungin treatment, consistent with its role in the cell wall integrity signaling (Figure 5C, +vector). In clear contrast, the phosphorylation of Spc1was only slightly induced upon micafungin treatment, although it was clearly induced upon KCl treatment. (Figure 5D, wt). In Δspc1 strain, no signal was detected upon KCl treatment, indicating that the signals detected by anti-phospho-p38 antibodies are indeed derived from the Spc1 MAPK (Figure 5D, Δspc1). Thus, the cell wall damage induced by micafungin mainly hyperactivates Pmk1 MAPK.

We further examined whether the overexpression of PP2C inhibits the Pmk1 signaling by regulating the levels of Pmk1 phosphorylation. For this, the effect of the overexpression of PP2C on micafungin-induced Pmk1 hyperphosphorylation was examined. Expectedly, the overexpression of Ptc1 (Ptc1 OP) and Ptc3 (Ptc3 OP) almost abolished the Pmk1 phosphorylation upon micafungin treatment (+vector), whereas Ptc2 overexpression (Ptc2 OP) had only a modest effect on the Pmk1 phosphorylation (Figure 5C). Thus, both Ptc1 and Ptc3 efficiently attenuated the Pmk1 signaling by modulating the Pmk1 phosphorylation, thereby controlling cell wall integrity.

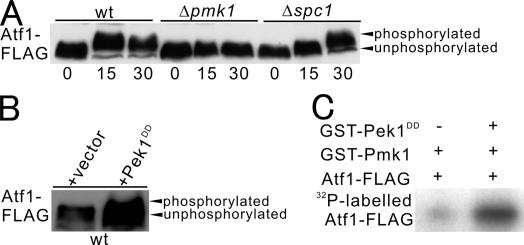

Pmk1 MAP Kinase Phosphorylates Atf1 on Cell Wall Stress

Next, we investigated whether the cell wall stress signal is transmitted to Atf1 through Pmk1. Atf1 was reported to be a substrate of Spc1 MAPK, and the Spc1-mediated phosphorylation of Atf1 caused Atf1 to migrate with reduced electrophoretic mobility (Degols and Russell, 1997). Thus by this method, we monitored the phosphorylation state of Atf1 in wild-type cells, Δpmk1 cells, and Δspc1 cells. In wild-type cells, the addition of micafungin to the media markedly reduced the mobility of the Atf1 protein tagged with FLAG in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, suggesting that micafungin treatment stimulated the phosphorylation of Atf1 (Figure 6A, wt). Notably, in Δpmk1 cells, the same treatment did not alter the mobility of Atf1 at all (Figure 6A, Δpmk1), indicating that the Atf1 mobility shift upon micafungin treatment is completely dependent on Pmk1 MAPK. However, in Δspc1 cells treated with micafungin for 30 min, the mobility shift of Atf1 was clearly seen compared with that of wild-type cells, although the migration was a little slower in Δspc1 cells at 15 min after the exposure to the stress compared with that of wild-type cells (Figure 6A, Δspc1).

Figure 6.

Pmk1 MAP kinase phosphorylates Atf1 in vivo and in vitro. (A) Pmk1-dependent phosphorylation of Atf1 after micafungin treatment. Wild-type, Δpmk1, or Δspc1 cells harboring pREP1-Atf1-FLAG were prepared as described in Figure 5C. Immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibodies showed that Atf1 is phosphorylated upon micafungin treatment in a Pmk1-dependent manner. (B) The activation of Pmk1 induced phosphorylation of Atf1. Wild-type cells containing pREP1-Atf1-FLAG and either the multicopy vector plasmid carrying Pek1DD or the control vector were prepared as described in Figure 6B. Immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibodies showed that Atf1 is phosphorylated by the overexpression of the constitutively active MAPKK Pek1DD. (C) Pmk1 phosphorylates Atf1 in vitro. Atf1-FLAG phosphorylation activity of GST-Pmk1 was measured in the presence or absence of GST-Pek1DD protein as indicated.

We also examined whether the activation of Pmk1 by the overexpression of Pek1 MAPKK induces a mobility shift of Atf1 in the absence of micafungin. Expectedly, the overexpression of the constitutively active Pek1DD resulted in the appearance of a hyperphosphorylated Atf1-FLAG band with reduced electrophoretic mobility as compared with that of the control vector (Figure 6B).

Moreover, we carried out in vitro kinase assay to evaluate whether the Pmk1-dependent phosphorylation of Atf1, as demonstrated by the data shown in Figure 6, A and B, might involve the direct phosphorylation of Atf1 by Pmk1 kinase. The results clearly showed that the addition of purified Pek1DD markedly stimulated the kinase activity of GST-Pmk1, thereby resulting in the phosphorylation of Atf1-FLAG (Figure 6C). Together these results suggest that Atf1 is a target of the Pmk1 MAPK.

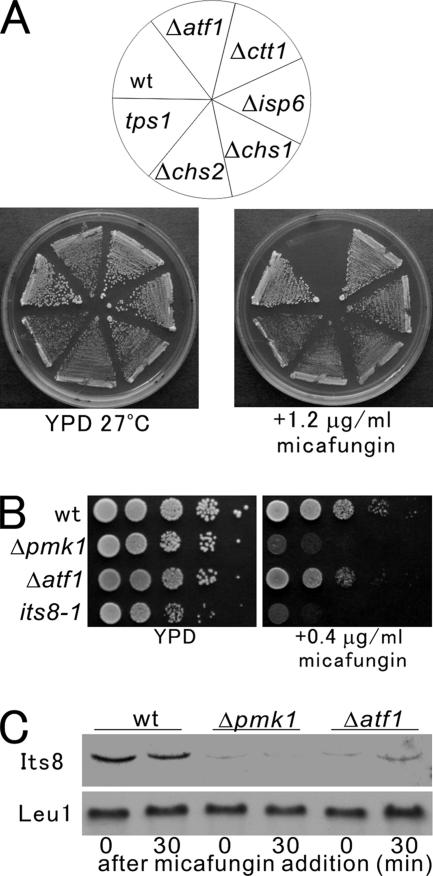

Identification of the Atf1 Target Genes for Cell Integrity

The above-mentioned results suggested that Atf1 has an important role as a key component of the Pmk1-mediated cell integrity signaling. This prompted us to search for the Atf1-regulated genes whose functions are relevant to the cell integrity phenotype.

As a first step, we investigated some of the Atf1-dependent genes previously determined by microarray experiments (Chen et al., 2003). As candidate genes, we chose tps1+, ctt1+, and isp6+, encoding glycosyltransferase, catalase, and vacuolar serine protease, respectively. To investigate whether these genes are involved in cell wall integrity, we examined the cell integrity phenotypes of mutants deleted for each of these candidate genes. As shown in Figure 7A, wild-type cells, tps1 mutant cells, Δctt1 cells, and Δisp6 cells grew well in the media containing 1.2 μg/ml micafungin, whereas Δatf1 cells failed to grow. Thus, although these candidate genes are regulated by Atf1, their functions seem not to be involved in micafungin resistance.

Figure 7.

Identification of the Atf1 target genes for cell integrity. (A) Phenotypes of various mutants. The cells as indicated were streaked onto the plates and then were incubated for 4 d at 27°C. (B) The its8-1 mutant showed hypersensitivity to micafungin. The cells as indicated were spotted onto the plates and then were incubated for 4 d at 27°C. (C) Its8 transcript is dependent on Pmk1-Atf1 signaling. Wild-type cells, Δpmk1 cells, and Δatf1 cells were incubated in YPD medium containing 1.0 μg/ml micafungin for 0 or 30 min, and cells were collected. Total RNA (20 μg) was subjected to Northern analysis by using a DIG-labeled Its8 or Leu1 cRNA.

Next, we investigated the effect of the loss of the chs1+ gene that encodes a chitin synthase in fission yeast, because Chs1 is one of the homologues of the cell wall biogenesis genes whose expression is regulated by the Mpk1-Rlm1 pathway in budding yeast. As shown in Figure 7A, Δchs1 cells, like wild-type cells, grew well in the media containing 1.2 μg/ml micafungin. Also, the deletion of the chs2+ gene did not alter the sensitivity to micafungin (Figure 7A).

We then examined the effect of the loss of mannoproteins on micafungin resistance, because mannoprotein is a major component of the cell wall. For this, we used the its8-1 mutant that we had previously isolated in a genetic screen for mutants that show immunosuppressant and temperature-sensitive growth (Yada et al., 2001). The its8+ gene encodes a homologue of the budding yeast MCD4 and human Pig-n that are involved in glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor synthesis. We also demonstrated that the its8-1 mutant showed cell integrity phenotypes, such as zymolyase sensitivity and cytokinesis defects. Notably, the growth of the its8-1 mutant cells was severely inhibited in the media containing 0.4 μg/ml micafungin, whereas the growth of the Δatf1 cells was moderately inhibited (Figure 7B). The sensitivity of the its8-1 mutant to the drug was similar to that of the Δpmk1 cells (Figure 7B).

We then examined the expression pattern of the its8 mRNA in wild-type cells, Δpmk1 cells and Δatf1 cells. In wild-type cells, the Its8 transcript was detectable in unstressed cells, and the levels of the its8+ mRNA were not significantly affected by micafungin treatment (Figure 7C, wt). In clear contrast, the Its8 transcript was only faintly detectable in Δpmk1 cells and Δatf1 cells, both before and after the micafungin treatment, indicating that its8+ gene expression is Pmk1-Atf1 dependent (Figure 7C). Together, these results suggest that Its8 is one of the Atf1-dependent genes for cell integrity.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the identification of two PP2Cs, namely, Ptc1 and Ptc3, as high-dosage suppressors of calcineurin deletion has led to the discovery that Atf1, a highly conserved transcription factor, serves as a target substrate of two MAPK pathways, namely, Spc1 MAPK and Pck/Pmk1 MAPK.

Here, we show that Atf1 is involved in the cell integrity signaling. First, mutants lacking atf1+ displayed hypersensitivity to micafungin, a cell wall-damaging agent. Second, Δatf1 cells but not the knockout mutants of the components of the Spc1 MAPK signaling exhibited vic phenotype, which is a strong indication of the involvement of the components of the Pmk1 signaling (Ma et al., 2006). Third, Pmk1 MAPK phosphorylates Atf1 in response to cell wall damage induced by micafungin. Fourth, the mRNA levels of its8+, encoding a mannoprotein involved in GPI-anchor synthesis and cell integrity, are Pmk1/Atf1 dependent. Thus, Atf1 is a novel downstream component of the Pck/Pmk1 MAPK pathway.

In budding yeast, genetic and biochemical studies showed that the Rlm1 transcription factor, which is related to the mammalian MEF2 isoforms, is phosphorylated and activated by the Mpk1/Slt2 MAP kinase in response to cell wall stress (Jung and Levin, 1999; Jung et al., 2002). Signaling through Mpk1-Rlm1 regulates the expression of at least 25 genes, most of which have been implicated in cell wall biogenesis. Unexpectedly, the deletion mutants of Mbx2, an Rlm1 homologue in fission yeast, displayed only a moderate sensitivity to cell wall-damaging agents, such as micafungin (Figure 5B). Also, the Mbx2 deletion cells exhibited only a weak vic phenotype (Figure 5B). Therefore, it is possible that in fission yeast, the Rlm1 homologue only plays a minor role in this process. This is a surprising result, because in budding yeast Rlm1 seems to have a central role in the Slt2/Mpk1 MAPK-mediated cell integrity signaling. In this context, our discovery that Atf1 is a key downstream component of Pmk1 in response to the cell integrity signaling may indicate that the Pmk1 signaling is transmitted largely through Atf1 and partly through Mbx2, which might explain the lack of cell integrity phenotypes in Mbx2 deletion in fission yeast. It might also explain the intermediate response of the Δatf1 cells for micafungin sensitivity and vic phenotype compared with that of the Δpmk1 and Δspc1 cells.

In higher eukaryotes, there is accumulating evidence of signaling cross-talk through the regulation of transcription factors, mainly by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. For example, Elk1, the most well characterized ternary complex factors, is a substrate for three MAPKs, and phospho-Elk1 can be dephosphorylated by calcineurin (Tian and Karin, 1999). The phosphorylation of Elk1 transcription factor stimulates c-fos promoter activity, whereas the dephosphorylation of Elk1 by calcineurin may play a role in turning off c-fos transcription (Tian and Karin, 1999).

In this context, it is intriguing to hypothesize that calcineurin dephosphorylates and inhibits Atf1 thereby antagonizing Pmk1 function. In our previous report, we showed that there is synergy between MAPK phosphatase Pmp1 and calcineurin, based on the high-dosage suppression of the Cl− hypersensitivity by Pmp1 and the synthetic lethal interaction of Δpmp1Δppb1 double mutant cells (Sugiura et al., 1998). We also raised the hypothesis that calcineurin and Pmk1 MAPK may share substrate(s) and regulate the activity of the substrate by dephosphorylation and phosphorylation, respectively. In the absence of calcineurin, the substrate accumulates in its phosphorylated state, which can be reversed by inhibiting the activity of the MAPK responsible for the phosphorylation event. One way to inhibit Pmk1 activity is the overexpression of Pmp1 or PP2Cs as evidenced in our present work. This scenario explains the cross-talk between Pmk1 signaling and calcineurin, although the basis of the biochemical mechanism accounting for this functional interaction or the target(s) of Atf1 remains unknown.

In conclusion, the identification and analyses of the PP2Cs have demonstrated for the first time the functional importance of the Atf1 transcription factor in cell integrity signaling through the protein kinase C-MAPK pathway. Given the high similarity between the fission yeast and the mammalian MAPK pathway, the genetic screen for the high-dosage suppressors of the Cl− hypersensitivity of calcineurin deletion or the screen for vic mutants may be useful in identifying novel components of the cell integrity-MAPK cascade to further understand the regulatory mechanisms of MAPK signaling in higher eukaryotes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Takashi Toda, Mitsuhiro Yanagida, Paul Russell, and Masayuki Yamamoto and Yeast Genetic Resource Center Japan supported by the National BioResource Project (YGRC/NBRP; http://yeast.lab.nig.ac.jp/nig) for providing strains and plasmids; Susie O. Sio and Matthew Thornton for critical reading of the manuscript; and Fujisawa Pharmaceutical for gifts of FK506. This work was supported by the 21st Century Center of Excellence Program, the Asahi Glass Foundation, the Uehara Memorial Foundation, and research grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. This work was also supported in part by the “Academic Frontier” Project for Private Universities: matching fund subsidy from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 2005–2007.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0282) on September 19, 2007.

REFERENCES

- Bähler J., Wu J., Longtine M. S., Shah N. G., McKenzie A., III, Steever A. B., Wach A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach D., Piper M., Nurse P. Construction of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene bank in a yeast bacterial shuttle vector and its use to isolate genes by complementation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1982;187:326–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00331138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck V., Ng S. S., Ruiz-Garcia A. B., Papadopoulou K., Bhatti S., Samuel J. M., Anderson M., Millar J. B., McInerny C. J. Fkh2p and Sep1p regulate mitotic gene transcription in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:5623–5632. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Toone W. M., Mata J., Lyne R., Burns G., Kivinen K., Brazma A., Jones N., Bahler J. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:214–229. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degols G., Russell P. Discrete roles of the Spc1 kinase and the Atf1 transcription factor in the UV response of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997;17:3356–3363. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds J. W., Mahadevan L. C. MAP kinases as structural adaptors and enzymatic activators in transcription complexes. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:3715–3723. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaits F., Degols G., Shiozaki K., Russell P. Phosphorylation and association with the transcription factor Atf1 regulate localization of Spc1/Sty1 stress-activated kinase in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1464–1473. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaits F., Russell P. Vacuole fusion regulated by protein phosphatase 2C in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:2647–2654. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskowitz I. MAP kinase pathways in yeast: for mating and more. Cell. 1995;80:187–197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama S., Sugiura R., Lu Y., Maeda T., Kawagishi K., Yokoyama M., Tohda H., Hama Y. G., Shuntoh H., Kuno T. Zinc finger protein Prz1 regulates Ca2+ but not Cl− homeostasis in fission yeast: identification of distinct branches of calcineurin signaling pathway in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:18078–18084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung U. S., Levin D. E. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression regulated by the yeast cell wall integrity signalling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;34:1049–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung U. S., Sobering A. K., Romeo M. J., Levin D. E. Regulation of the yeast Rlm1 transcription factor by the Mpk1 cell wall integrity MAP kinase. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;46:781–789. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrer K., Domdey H. Preparation of high molecular weight RNA. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:398–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin D. E. Cell wall integrity signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005;69:262–291. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.2.262-291.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin D. E., Errede B. The proliferation of MAP kinase signaling pathways in yeast. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1995;7:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Kuno T., Kita A., Asayama Y., Sugiura R. Rho2 is a target of the farnesyltransferase Cpp1 and acts upstream of Pmk1 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:5028–5037. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T., Wurgler-Murphy S. M., Saito H. A two-component system that regulates an osmosensing MAP kinase cascade in yeast. Nature. 1994;369:242–245. doi: 10.1038/369242a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C. J. MAP kinase kinase kinase, MAP kinase kinase and MAP kinase. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1994;4:82–89. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo Y., Tanaka K., Nakagawa T., Matsuda H., Kawamukai M. Genetic analysis of chs1+ and chs2+ encoding chitin synthases from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004;68:1489–1499. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S., Klar A., Nurse P. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:795–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94059-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A. N., Shiozaki K. Heat-shock-induced activation of stress MAP kinase is regulated by threonine- and tyrosine-specific phosphatases. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1653–1663. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.13.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida E., Gotoh Y. The MAP kinase cascade is essential for diverse signal transduction pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1993;18:128–131. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90019-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt G. M., Price C. Isolation of a Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene which in high copy confers resistance to the nucleoside analogue 5-azacytidine. Yeast. 1997;13:463–474. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199704)13:5<463::AID-YEA89>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. J. One-step gene disruption in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengar A. S., Markley N. A., Marini N. J., Young D. Mkh1, a MEK kinase required for cell wall integrity and proper response to osmotic and temperature stress in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997;17:3508–3519. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki K., Akhavan-Niaki H., McGowan C. H., Russell P. Protein phosphatase 2C, encoded by ptc1+, is important in the heat shock response of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell Biol. 1994;14:3742–3751. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki K., Russell P. Counteractive roles of protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) and a MAP kinase kinase homolog in the osmoregulation of fission yeast. EMBO J. 1995;14:492–502. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozaki K., Russell P. Conjugation, meiosis, and the osmotic stress response are regulated by Spc1 kinase through Atf1 transcription factor in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2276–2288. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sio S. O., Suehiro T., Sugiura R., Takeuchi M., Mukai H., Kuno T. The role of the regulatory subunit of fission yeast calcineurin for in vivo activity and its relevance to FK506 sensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12231–12238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura R., Kita A., Kuno T. Upregulation of mRNA in MAPK signaling: transcriptional activation or mRNA stabilization? Cell Cycle. 2004;3:286–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura R., Kita A., Shimizu Y., Shuntoh H., Sio S. O., Kuno T. Feedback regulation of MAPK signalling by an RNA-binding protein. Nature. 2003;424:961–965. doi: 10.1038/nature01907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura R., Sio S. O., Shuntoh H., Kuno T. Calcineurin phosphatase in signal transduction: lessons from fission yeast. Genes Cells. 2002;7:619–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura R., Toda T., Dhut S., Shuntoh H., Kuno T. The MAPK kinase Pek1 acts as a phosphorylation-dependent molecular switch. Nature. 1999;399:479–483. doi: 10.1038/20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura R., Toda T., Shuntoh H., Yanagida M., Kuno T. pmp1+, a suppressor of calcineurin deficiency, encodes a novel MAP kinase phosphatase in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1998;17:140–148. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekawa M., Maeda T., Saito H. Protein phosphatase 2Calpha inhibits the human stress-responsive p38 and JNK MAPK pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:4744–4752. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J., Karin M. Stimulation of Elk1 transcriptional activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases is negatively regulated by protein phosphatase 2B (calcineurin) J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15173–15180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.15173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda T., Dhut S., Superti F. G., Gotoh Y., Nishida E., Sugiura R., Kuno T. The fission yeast pmk1+ gene encodes a novel mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog which regulates cell integrity and functions coordinately with the protein kinase C pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:6752–6764. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda T., Shimanuki M., Yanagida M. Two novel protein kinase C-related genes of fission yeast are essential for cell viability and implicated in cell shape control. EMBO J. 1993;12:1987–1995. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson M. G., Samuels M., Takeda T., Toone W. M., Shieh J. C., Toda T., Millar J. B., Jones N. The Atf1 transcription factor is a target for the Sty1 stress-activated MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2289–2301. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yada T., Sugiura R., Kita A., Itoh Y., Lu Y., Hong Y., Kinoshita T., Shuntoh H., Kuno T. Its8, a fission yeast homolog of Mcd4 and Pig-n, is involved in GPI anchor synthesis and shares an essential function with calcineurin in cytokinesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:13579–13586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T., Toda T., Yanagida M. A calcineurin-like gene ppb1+ in fission yeast: mutant defects in cytokinesis, cell polarity, mating and spindle pole body positioning. J. Cell Sci. 1994;107:1725–1735. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.7.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivancos A. P., Castillo E. A., Jones N., Ayté J., Hidalgo E. Activation of the redox sensor Pap1 by hydrogen peroxide requires modulation of the intracellular oxidant concentration. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;52:1427–1435. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsevskaya-Carter T., Cooper J. A. Spm1, a stress-activated MAP kinase that regulates morphogenesis in S. pombe. EMBO J. 1997;16:1318–1331. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]