Abstract

A novel solvent-exposed analyte channel, generated by F165G substitution, on the surface of green fluorescent protein (designated His6GFPuv/F165G) was successfully discovered by the aid of molecular modeling software (PyMOL) in conjunction with site-directed mutagenesis. Regarding the high predictive performance of PyMOL, two pore-containing mutants namely His6GFPuv/H148G and His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G were also revealed. The pore sizes of F165G, H148G, and the double mutant H148G/F165G were in the order of 4, 4.5 and 5.5 Å, respectively. These mutants were subjected to further investigation on the effect of small analytes (e.g. metal ions and hydrogen peroxide) as elucidated by fluorescence quenching experiments. Results revealed that the F165G mutant exhibited the highest metal sensitivity at physiological pH. Meanwhile, the other 2 mutants lacking histidine at position 148 had lower sensitivity against Zn2+ and Cu2+ than those of the template protein (His6GFPuv). Hence, a significant role of this histidine residue in mediating metal transfer toward the GFP chromophore was proposed and evidently demonstrated by testing in acidic condition. Results revealed that at pH 6.5 the order of metal sensitivity was found to be inverted whereby the H148G/F165G became the most sensitive mutant. The dissociation constants (Kd) to metal ions were in the order of 4.88×10-6 M, 16.67×10-6 M, 25×10-6 M, and 33.33×10-6 M for His6GFPuv/F165G, His6GFPuv, His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G and His6GFPuv/H148G, respectively. Sensitivity against hydrogen peroxide was in the order of H148G/F165G > H148G > F165G indicating the crucial role of pore diameters. However, it should be mentioned that H148G substitution caused a markedly decrease in pH- and thermo-stability. Taken together, our findings rendered the novel pore of GFP as formed by F165G substitution to be a high impact channel without adversely affecting the intrinsic fluorescent properties. This opens up a great potential of using F165G mutant in enhancing the sensitivity of GFP in future development of biosensors.

Keywords: analyte channel, Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), molecular modeling, analyte sensitivity, site-directed mutagenesis

1. Introduction

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) from Aequorea victoria is widely established as a superlative biological macromolecule prevalent in basic research and applied sciences due to its autofluorescence and high stability. The fluorescent activity (λex and λem at 395 and 509 nm, respectively) is generated by autocatalytic cyclization of the tripeptide Ser65Tyr66Gly67 to form 4-(p-hydroxybenzylidene)-imidazolidin-5-one. GFP is stable in various hazardous conditions including a wide range of pH (2-14), high temperature (Tm at 78°C), strong denaturants (up to 8M urea and 6M guanidine hydrochloride) and protease digestion 1. This is attributed to the tightly packed protein structure comprising of 11 antiparallel β-strands encompassing the chromophore and shielding it from the solvent 2. GFP has been extensively used as markers of gene expression 3, 4, protein localization 5, 6, protein-protein interaction 7, 8 and immunological diagnosis 9, 10. GFP and its variants have also been used as analytical sensors of voltage-dependent cations 11-13, protons 14-17, halides 18-20, and metal ions 21-24. However, it should be noted that the robust nature of the GFP barrel impedes the accessibility of analytes to the chromophore and its subsequent quenching effect which is crucial for sensor applications. Therefore, durable GFP able to maintain high sensitivity toward analytes is highly desirable.

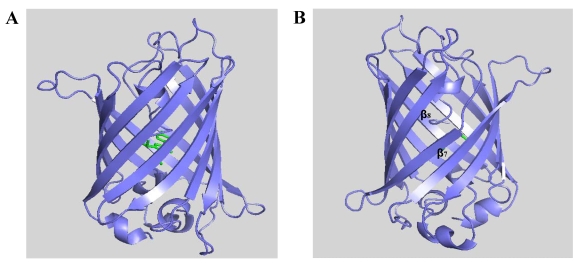

In the post-genomic era, computational analysis and molecular modeling have been widely used to facilitate the design and study of biomolecules for cellular investigations 25. PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC) is a robust molecular modeling software allowing the visualization of three-dimensional molecular structures as well as enabling in silico mutagenesis of proteins. Based on the crystal structure of GFPuv (PDB entry 1B9C), it is important to note that there is an unusual interstrand bonding between the seventh and eighth β-strands (Fig. 1). This interstrand space is possibly formed during the folding process of the GFP β-barrel 26. The dynamic conformational processes and inefficient side chain packing inside the GFP β-barrel, probably give rise to diverging β-strands with large interstrand distance 26. Hence, we hypothesize that such region is a potential target site for rationally engineering a channel for analytes to access the chromophore. Although, a solvent-accessible channel formed by H148G mutation has previously been reported in YFP 27 and BFPms1 28, this substitution has been found to augment the structural fluctuation and disturb the fluorescence property of GFP 26. Due to the essential role of His148 in maintaining the intricate hydrogen bonding network with the GFP chromophore 29-31, it is particularly important to search for alternative channels that render similar sensitivity effect on the GFP in response to small analytes without detrimentally perturbing the intrinsic fluorescence and structural integrity.

Fig 1.

Molecular structure of GFPuv (PDB entry 1B9C). The eleven β-strands of GFP are arranged into a barrel-like structure encompassing the centrally located chromophore (A). Rotation of the structure to the other side (B) reveals the interstrand space between β-strands 7 and 8.

In the present study, we combine molecular modeling and site-directed mutagenesis to construct novel solvent-exposed channels on the surface of GFP. Glycine-scanning mutagenesis was performed virtually with molecular modeling software to search for potential surface residues giving rise to solvent-accessible channels. Once the key residues were identified, actual site-directed mutagenesis was performed to obtain the desired mutants. The sensitivity of GFP mutants against small analytes such as metal cations and H2O2 was investigated by observing the fluorescence quenching effect. This rational design approach has allowed the identification of novel solvent-accessible channels on the surface of GFP that possess sensitivity toward analytes of interest while maintaining structural and functional integrity.

2. Materials and Methods

In silico mutagenesis

Visualization of the molecular structure of GFPuv (PDB entry 1B9C) was performed using PyMOL. Virtual glycine-scanning mutagenesis was achieved by substituting each surface residue with glycine in attempts to minimize bulky side chains. Mutants giving rise to solvent-exposed analyte channel on the protein surface after amino acid substitution(s) was chosen for further investigation.

Site-directed mutagenesis for amino acid substitution of F165G and H148G on GFPuv

Pore-containing GFPuv mutants, F165G and H148G (substitution of phenylalanine and histidine at position 165 and 148 with glycine, respectively), were constructed using QuikChange® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The mutagenic primers used in this study are as follows: F165G_forward 5′-CAAAGCTAACGGCAAAATTCGCCACAACATTGAAGATGGCTCCG-3′ and F165G_reverse 5′-CGGAGCCATCTTCAATGTTGTGGCGAATTTTGCCGTTAGCTTTG-3′; H148G_forward 5′-CAACTATAACTCAGGCAATGTATACATCACTGCAGAC-3′ and H148G_reverse 5′-GTCTGCAGTGATGTATACATTGCCTGAGTTATAGTTG-3′ (Note: codon substitutions are shown bold, while deletion of BamHI site and the introduction of PstI site used for gene verification are shown as underlined). PCR mutagenesis was carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, a 50-μl reaction mixture comprising of 50 ng of template plasmid DNA (pHis6GFPuv) 21, 125 ng of each primer, 1 μl of dNTP mixture and 2.5 U of PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was prepared. PCR amplification was performed under the desired condition as follows: initial denaturation at 95 ºC for 30 seconds; 16 cycles at 95 ºC for 30 seconds, 55 ºC for 1 minute and 68 ºC for 4 minutes; final-extension at 68 ºC for 10 minutes. Subsequently, 1 μl of the restriction enzyme DpnI (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was added to the sample and kept at 37 ºC for 1 hour in order to obtain complete digestion of the template plasmid. Next, 1 μl of the sample was transformed into E. coli strain XL1-Blue competent cells by the Ca2+-coprecipitation method. Transformants possessing green fluorescence were selected and site-specific mutation on the gfp gene was verified via restriction endonucleases analysis.

Protein expression and purification

The starter culture was prepared by inoculating a single colony into 5 ml LB broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and grown overnight at 37 ºC with agitation at 150-180 rpm. A 100-fold dilution was prepared and incubated at 37 ºC to reach a density of approximately OD600 = 0.5. Gene expression was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). After overnight incubation, the culture was harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 g at 4 ºC for 10 minutes. The cell pellet was resuspended in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and subsequently disrupted by sonic disintegration. The debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 g at 4 ºC for 10 minutes. Purification of mutated GFP from crude extract was performed using IMAC-Zn2+ affinity chromatography as previously described 21. Estimation of molecular size and protein purity was performed on a 12% polyacrylamide gel in Tris-glycine, pH 8.3 discontinuous buffer system. Protein concentration was quantitated with the protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin as standard.

Fluorescence scanning

The fluorescent excitation and emission spectra of all GFP mutants (adjusted at 300 nM) in PBS buffer were recorded on Perkin-Elmer spectrofluorometer FP6300 at room temperature. Excitation and emission spectra were attained by means of emission at 509 nm and excitation at 395 nm, respectively.

Thermal and pH stability testing

All pore-containing GFP mutants were subjected to heat treatment at specified temperature (25-90 ºC) for 10 minutes and then rapidly cooled down to room temperature. Fluorescence was instantaneously measured at 509 nm (FLx 800 fluorometer, BIO-TEK instrument, USA) upon activation with 395 nm light. In parallel, individual proteins were incubated in Tris-buffer (containing 5 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM glycine, 10 mM sodium citrate or 10 mM sodium phosphate) at various pHs for 10 minutes prior to fluorescence measurements.

Effect of small molecules on the fluorescent intensity of pore-containing GFPuv mutants

To investigate the effect of small molecules on the fluorescent intensity of the GFP mutants, equal amounts (10 μg) of the purified proteins were mixed with various concentrations of charged (Zn2+, Cu2+) or uncharged compound (H2O2) in phosphate buffer at pH 6.5 and 7.4. The fluorescence response was kinetically recorded and analyzed.

3. Results and discussion

In silico mutagenesis of pore-containing GFPuv mutants

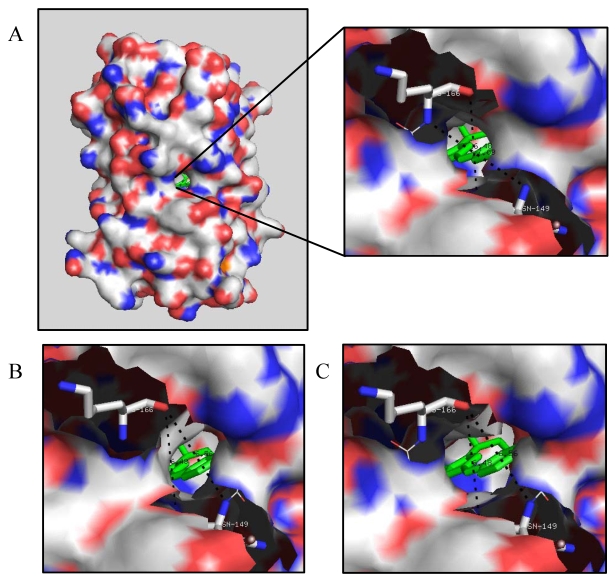

Molecular modeling revealed a potential analyte channel on the surface of GFP barrel at the Phe165 located on the eighth strand upon mutating to glycine (Fig. 2A). Such high predictability could also account for the discovery of pore formation at His148 (Fig. 2B), which is consistent with other investigations on YFP and BFPms1 27, 28. More importantly, results from the modeling studies indicated that the double mutant H148G/F165G provided a larger pore size diameter of 5.5 Å (Fig. 2C), than the single mutants H148G and F165G with pore sizes of only 4.5 and 4 Å, respectively (Figs. 2B and 2A).

Fig 2.

Electrostatic surface of the GFP mutants: F165G (A), H148G (B), and H148G/F165G (C). The rationally engineered analyte channels expose the chromophore (green) to environmental solvents. The electrostatic potential is mapped onto the protein molecular surface showing positively (blue) and negatively (red) charged regions.

Construction of pore-containing mutants of GFPuv via site-directed mutagenesis

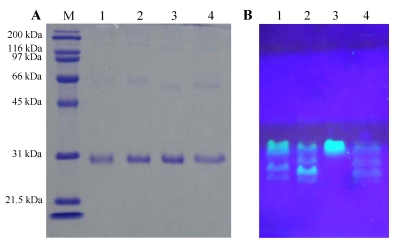

Three pore-containing mutants of GFPuv, comprising of His6GFPuv/H148G, His6GFPuv/F165G and His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G, were successfully constructed using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. Mutated genes were verified by the presence of silent mutation at PstI and BamHI recognition sites as generated by the mutagenic primers. The mutagenized PCR-product was expressed in E. coli XL1-Blue cells followed by protein purification with IMAC-Zn2+. As judged by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3), the purified His6GFPuv and its mutants displayed a molecular weight of approximately 30 kDa with purity in excess of 95%. Interestingly, His6GFPuv/F165G exhibited the highest fluorescent intensity as compared with His6GFPuv and its mutants. This indicated no perturbation to fluorescence emission of the single point mutant, F165G. On the other hand, the double mutant, H148G/F165G, generated the lowest fluorescence. Such findings support the notion that removal of bulky amino acid at positions 148 and 165 potentially promotes electron transfer throughout the GFP chromophore.

Fig 3.

Comparison of molecular mass (A) and fluorescent intensity (B) of template His6GFPuv and its mutants. Molecular weight marker (lane M), His6GFPuv (lane 1), His6GFPuv/H148G (lane 2), His6GFPuv/F165G (lane 3), and His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G (lane 4).

Fluorescence spectra of pore-containing GFPs

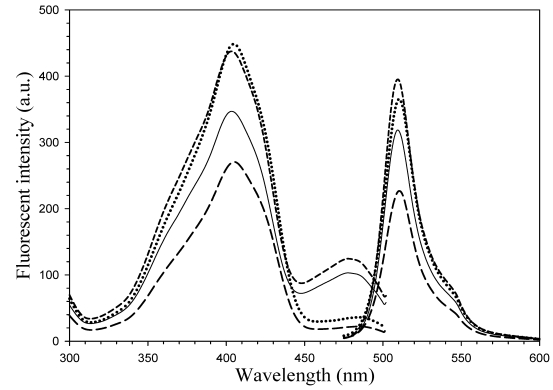

The excitation and emission maxima of all pore-containing mutants were found to situate at 403 and 510 nm, respectively. This revealed a non-significant alteration on the fluorescence spectra (Fig. 4) upon substitution of Phe 165 and His 148 with glycine. However, disparity in magnitude on the fluorescent emission was detected particularly on the double mutant, H148G/F165G. Moreover, the peak of anionic chromophore (located at 478 nm) was distinctively reduced upon replacement of His148 (as evidenced in H148G and H148G/F165G mutants). Our findings strongly support the role of His148 in maintaining the intrinsic fluorescence activity via hydrogen bonding to the chromophore 26, 32. Replacing this residue has been shown to reduce the absorption of the anionic state of the chromophore as well as affect the conformational stability 26. All of these findings suggest the importance of F165G in providing a solvent-accessible channel without adversely affecting the fluorescent properties.

Fig 4.

Fluorescence spectra of His6GFPuv (solid line), His6GFPuv/H148G (dot line), His6GFPuv/F165G (short-dash line) and His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G (long-dash line).

Stability of pore-containing GFPs

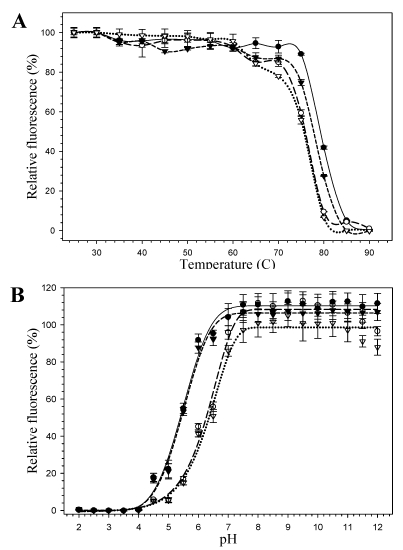

The pore-containing mutants were further exposed to heat and acid-base conditions. At 60 ºC for 10 minutes, all mutants were still able to maintain their fluorescence. However, at 80 ºC, 10 minutes, fluorescence of the mutants bearing substitution at position 148 (His6GFPuv/H148G and His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G) dropped to zero while the His6GFPuv and the His6GFPuv/F165G were able to retain their fluorescence of up to 40% and 30%, respectively (Fig. 5A). Our findings suggest that removal of His 148 led to the perturbation of the overall protein structure. Destabilization and structural fluctuation of GFP barrel upon H148G substitution has previously been documented 26. Despite of the various degree of heat susceptibility, all mutants fell into the same range (76-79 ºC) of melting temperature.

Fig 5.

Relative fluorescence of His6GFPuv (closed circle), His6GFPuv/H148G (opened circle), His6GFPuv/F165G (closed triangle), and His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G (opened triangle) as a function of temperature (A) and pH (B). The samples (10 μg) were excited at 395 nm followed by determination of the emission intensity at 509 nm.

Reduction of the fluorescence activity was correlated with decrease in pH as can be seen from the proton and fluorescence response curve (Fig. 5B) for His6GFPuv and its variants. At extreme acidic pH (~ pH 4.0), complete loss of fluorescence was observed for all mutants. However, changes in the relative fluorescence of His6GFPuv and F165G mutant were slightly less than those of the H148G and H148G/F165G mutants. The pH stability of His6GFPuv and His6GFPuv/F165G were nearly identical, whereas His6GFPuv/H148G and His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G were more pH-sensitive. At pH 6.0, His6GFPuv and F165G mutant were still able to maintain their fluorescence activity of up to 90% whereas H148G and H148G/F165G variants exhibited only 40% fluorescence. All GFP proteins gave maximal fluorescent activity when pH was raised above 7.5.

Effect of small molecules on the fluorescent intensity of pore-containing mutants

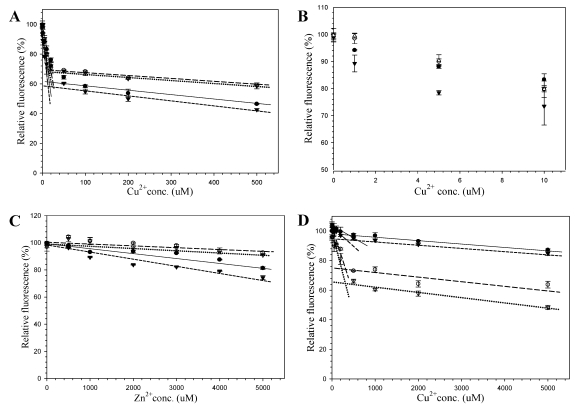

In order to demonstrate the efficacy of this channel in facilitating the accessibility of small molecules, metal cations and hydrogen peroxide were selected as representatives of charged and neutral compounds for the fluorescent quenching experiment. The fluorescence response of pore-containing GFP mutants in comparison with the template protein is shown in Fig. 6. Both Cu2+ (Fig. 6A) and Zn2+ (Fig. 6C) ions reduced fluorescent emission of all proteins in a concentration dependent manner. For all metal concentrations tested, His6GFPuv/F165G provided the highest sensitivity at physiological pH. Interestingly, response against Cu2+ was likely to be biphasic in decreasing the fluorescent intensity. Upon addition of 20 μM, a rapid decrease (phase 1) in fluorescent intensity of up to 30-40% was observed for all GFPs (Figs. 6A and 6B), followed by a gradual decrease (phase 2) in the fluorescent intensity (Fig. 6A). Changes in rate and magnitude of fluorescent reduction during the first phase as well as the second phase were found to be dependent on the metal concentration. The greatest difference in fluorescence reduction between His6GFPuv and His6GFPuv/F165G were approximately 10% for both metal cations. The decline of fluorescence reached almost the plateau phase after addition of 50 μM Cu2+ or 1 mM Zn2+, possibly due to saturation of metal ions inside the β-barrel of GFP.

Fig 6.

Effect of copper and zinc ions on the fluorescent emission of purified His6GFPuv (closed circle), His6GFPuv/H148G (opened circle), His6GFPuv/F165G (closed triangle), and His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G (opened triangle). The fluorescent quenching experiments were carried out at pH 7.4 for copper (A, B) and zinc (C), and at pH 6.5 for copper (D).

From the aforementioned results, it seemed that the diameter of the channel had no effect on the quenching activity of metal ions. Therefore, subsequent experiment was conducted to test the effect of metal ions at more acidic condition (pH 6.5). As observed from Fig. 6D, the order of metal sensitivity was in the opposite direction. The largest pore mutant, His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G, displayed the greatest sensitivity toward metals at all concentrations. This result strongly supports the role of His148 in regulating the solvent accessible channel of the β-barrel. Similar studies have shown that the binding affinity of polyhistidine tag or imidazole toward metal ions are dramatically decreased in acidic condition, especially when the pH is lower than its pKa 33, 34. Therefore, protonation of the imidazole group of histidine residues caused a reduction in the sensitivity of His148 mutants as compared to those of pH 7.4. In addition, several residues surrounding the designed channels may also be protonated and cause electrostatic repulsion of the metal ions. Thus, ten folds of copper ions were required to achieve the same level of fluorescence reduction.

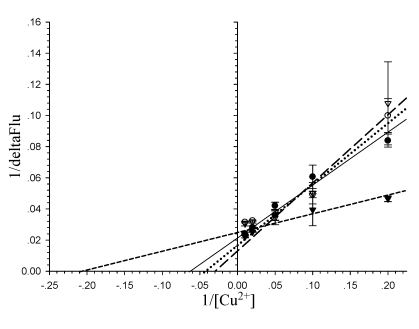

To explain the sensitivity toward metal ions of the pore-containing mutants, the dissociation constant (Kd) of the proteins toward Cu2+ ions at neutral pH was determined from the Lineweaver-Burk plot (Fig. 7). In order of increasing Kd the following was observed: His6GFPuv/F165G (4.878×10-6 M) < His6GFPuv (16.67×10-6 M) < His6GFPuv/H148G/ F165G (25×10-6 M) < His6GFPuv/H148G (33.33×10-6 M). Possible explanation for the observed low Kd of His6GFPuv/F165G may not be attributed to the higher affinity toward Cu2+ ions, but is possibly due to the metal-channeling effect as described previously in which greater amounts of metal ions may be found in close proximity to the chromophore as provided by His148.

Fig 7.

Determination of the dissociation constant of copper with His6GFPuv (closed circle), His6GFPuv/H148G (opened circle), His6GFPuv/F165G (closed triangle), and His6GFPuv/H148G/F165G (opened triangle). Calculations were performed and fitted to the Lineweaver-Burk plot. The values shown were derived from the average of triplicate samples.

Analogously, the uncharged compound, H2O2, exerted a suppressing effect on the fluorescence of GFP and its mutants. Unlike the quenching phenomenon by metal ions, H2O2 was clearly shown to be pore size-dependent in which the double mutant, H148G/F165G, with a size of 5.5 Å, was observed to be the most sensitive. This can be attributed to the fact that H2O2 can enter the GFP barrel passively without engaging in electrostatic repulsion or specific interaction with particular amino acids involved in metal coordination. Therefore, larger pore is expected to allow more compounds into the GFP can, subsequently quenching the fluorescent activity in a dose-dependent manner. However, it should be noted that reduction in fluorescence of approximately 10% was observed in the presence of 1.4 M H2O2, which indicates the stability of the mutants even at high peroxide concentration.

In conclusion, this work explores the potential applications of molecular modeling along with site-directed mutagenesis for the construction of solvent-exposed analyte channel on the surface of GFP without influencing the intrinsic fluorescent properties and protein stabilities. Owing to its autofluorescent nature and extreme stability, GFP can be considered as a superlative biological molecule in sensor research. However, such stability probably contributes to the low sensitivity of GFP towards small analytes. A solvent-accessible channel made possible by H148G mutation of BFP was reported previously. The channel allows passage of analytes of interest into the β-barrel. However, such amino acid substitution considerably affected the fluorescent properties and structural stabilities of GFP. The novel F165G mutant discovered herein, possessing the solvent accessible channel while retaining stable and fluorescent properties, offers great potential for further design and development of highly-sensitive fluorescent-based sensor for biological and environmental applications.

Acknowledgments

N.T. was financially supported by the Royal Golden Jubilee (RGJ) Ph.D. scholarship under supervision of V.P. This project was also supported by the annual budget grant of Mahidol University (No. 02012053-0003).

References

- 1.Tsien RY. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ormo M, Cubitt AB, Kallio K et al. Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Science. 1996;273:1392–5. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welsh S, Kay SA. Reporter gene expression for monitoring gene transfer. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1997;8:617–22. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(97)80038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotarsky K, Owman C, Olde B. A chimeric reporter gene allowing for clone selection and high-throughput screening of reporter cell lines expressing G-protein-coupled receptors. Anal Biochem. 2001;288:209–15. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bastiaens PI, Pepperkok R. Observing proteins in their natural habitat: the living cell. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:631–7. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01714-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Snapp E, Kenworthy A. Studying protein dynamics in living cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:444–56. doi: 10.1038/35073068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day RN. Visualization of Pit-1 transcription factor interactions in the living cell nucleus by fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1410–9. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.9.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahajan NP, Linder K, Berry G et al. Bcl-2 and Bax interactions in mitochondria probed with green fluorescent protein and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:547–52. doi: 10.1038/nbt0698-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prachayasittikul V, Isarankura Na Ayudhya C, Suwanwong Y et al. Construction of chimeric antibody binding green fluorescent protein for clinical application. EXCLI Journal. 2005;4:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suwanwong Y, Isarankura Na Ayudhya C, Bulow L et al. Insights into the genetic re-engineering of chimeric antibody-binding green fluorescent proteins for immunological taggers. EXCLI Journal. 2006;5:164–78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker BJ, Lee H, Pieribone VA et al. Three fluorescent protein voltage sensors exhibit low plasma membrane expression in mammalian cells. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;161:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimitrov D, He Y, Mutoh H et al. Engineering and characterization of an enhanced fluorescent protein voltage sensor. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Souslova EA, Belousov VV, Lock JG et al. Single fluorescent protein-based Ca2+ sensors with increased dynamic range. BMC Biotechnol. 2007;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miesenbock G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 1998;394:192–5. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Llopis J, McCaffery JM, Miyawaki A et al. Measurement of cytosolic, mitochondrial, and Golgi pH in single living cells with green fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6803–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porcelli AM, Ghelli A, Zanna C et al. pH difference across the outer mitochondrial membrane measured with a green fluorescent protein mutant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:799–804. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arosio D, Garau G, Ricci F et al. Spectroscopic and structural study of proton and halide ion cooperative binding to gfp. Biophys J. 2007;93:232–44. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.102319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jayaraman S, Haggie P, Wachter RM et al. Mechanism and cellular applications of a green fluorescent protein-based halide sensor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6047–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galietta LJ, Haggie PM, Verkman AS. Green fluorescent protein-based halide indicators with improved chloride and iodide affinities. FEBS Lett. 2001;499:220–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02561-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzola PG, Ishii M, Chau E et al. Stability of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in chlorine solutions of varying pH. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22:1702–7. doi: 10.1021/bp060217i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prachayasittikul V, Isarankura Na Ayudhya C, Mejare M et al. Construction of a chimeric histidine6-green fluorescent protein: role of metal on fluorescent characteristic. Thammasat Int J Sci Technol. 2000;5:61–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prachayasittikul V, Isarankura Na Ayudhya C, Bulow L. Lighting E. coli cells as biological sensors for Cd2+ Biotechnol Lett. 2001;23:1285–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richmond TA, Takahashi TT, Shimkhada R et al. Engineered metal binding sites on green fluorescence protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:462–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eli P, Chakrabartty A. Variants of DsRed fluorescent protein: Development of a copper sensor. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2442–7. doi: 10.1110/ps.062239206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nantasenamat C, Isarankura Na Ayudhya C, Tansila N et al. Prediction of GFP spectral properties using artificial neural network. J Comput Chem. 2007;28:1275–89. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seifert MH, Georgescu J, Ksiazek D et al. Backbone dynamics of green fluorescent protein and the effect of histidine 148 substitution. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2500–12. doi: 10.1021/bi026481b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wachter RM, Elsliger MA, Kallio K et al. Structural basis of spectral shifts in the yellow-emission variants of green fluorescent protein. Structure. 1998;6:1267–77. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barondeau DP, Kassmann CJ, Tainer JA et al. Structural chemistry of a green fluorescent protein Zn biosensor. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3522–4. doi: 10.1021/ja0176954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lill MA, Helms V. Proton shuttle in green fluorescent protein studied by dynamic simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2778–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052520799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saxena AM, Udgaonkar JB, Krishnamoorthy G. Protein dynamics control proton transfer from bulk solvent to protein interior: A case study with a green fluorescent protein. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1787–99. doi: 10.1110/ps.051391205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang R, Nguyen MT, Ceulemans A. A concerted mechanism of proton transfer in green fluorescent protein. A theoretical study. Chem Phys Lett. 2005;404:250–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brejc K, Sixma TK, Kitts PA et al. Structural basis for dual excitation and photoisomerization of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2306–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen WY, Wu CF, Liu CC. Interaction of imidazole and proteins with immobilized Cu (II) ions: Effects of structure, salt concentration, and pH in affinity and binding capacity. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1996;180:135–43. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson RD, Todd RJ, Arnold FH. Multipoint binding in metal-affinity chromatography II. Effect of pH and imidazole on chromatographic retention of engineered histidine-containing cytochromes c. J Chromatogr A. 1996;725:225–35. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)00992-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]