Abstract

Sphingosine kinase (SK) is the signaling enzyme that phosphorylates sphingosine to produce Sphingosine-1-phosphate. Sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) belong to a class of bioactive sphingolipid metabolites that are critical in a number of cellular processes, yet often have opposing biological functions. The intracellular localization of sphingosine kinase has been shown in multiple studies to be a critical aspect of its signaling function. To date, assays of sphingosine kinase activity have been developed for measuring activity in lysates, where the effects of localization are lost. Here we outline a system in which the rate of production of S1P can be measured in intact cells using exogenously added radiolabeled-ATP instead of tritiated sphingosine. The surprising ability of ATP to enter unpermeabilized monolayers is one aspect that makes this assay simple, efficient, and inexpensive, yet sensitive enough to measure endogenous enzyme activity. The assay is well behaved in terms of kinetics and substrate dependence. Overall, this assay is ideal for future studies to identify changes in S1P production in intact cells such as those that result from the differential intracellular targeting of sphingosine kinase.

Keywords: sphingosine kinase, sphingosine, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), sphingolipids, lipid second messengers

Introduction

Sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) belong to a class of sphingolipid metabolites that continue to emerge as key bioactive signaling molecules in a number of cellular processes [1–3]. Included in this class of lipid second messengers is the lipid precursor for sphingosine, ceramide. Specific roles for these sphingolipids have been established in diverse cellular events including proliferation, survival, differentiation, migration, apoptosis, lymphocyte recirculation, inflammatory response, and calcium fluxes [4–16]. Sphingosine kinase (SK) is the signaling enzyme that phosphorylates sphingosine to produce S1P. There are two known mammalian isoforms, SK1 and SK2 [17–19]. The work presented here focuses on human SK1.

One unique aspect of S1P signaling is that the lipid precursors for this molecule, sphingosine and ceramide, have signaling roles that often result in opposing effects on cell fate. Whereas generation of S1P plays a role in cell proliferation and survival [4;5], signaling levels of sphingosine and ceramide can result in growth arrest and apoptosis [11;20]. Like many signaling molecules, the intracellular levels of S1P are controlled by tightly regulating the balance between synthesis and degradation. After being generated by sphingosine kinase, there are several metabolic fates that await S1P [1]. In terms of degradation, S1P is irreversibly cleaved by S1P lyase to form phosphoethanolamine and palmitaldehyde [21]. This is the only irreversible interconversion within the sphingolipid metabolic network, therefore the phosphorylation of sphingosine by SK1 controls sphingolipid degradation. Alternatively, S1P is dephosphorylated by several isoforms of S1P phosphatase to regenerate sphingosine [22;23]. This sphingosine can then be utilized for ceramide synthesis. It is apparent that the activity of sphingosine kinase plays a pivotal role in regulating the levels of multiple bioactive sphingolipid molecules with divergent roles.

As a signaling enzyme, sphingosine kinase-1 can be activated by numerous external stimuli including phorbol ester, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), and cyclic AMP, among others [24–26]. This activation is often very transient. When activated by agonists, SK1 translocates from internal sites to the plasma membrane (PM). While the molecular mechanisms that mediate SK1 translocation remain unclear, there is considerable evidence that implicates localization of SK1 as a critical aspect of its signaling function [27–29]. In essence, the differential localization of SK1 to distinct intracellular membranes could have multiple effects on sphingolipid metabolism. First, SK1 could be targeted to distinct pools of lipid substrates. This would have the potential of reducing the levels of sphingosine, and its precursor ceramide, below their signaling capacity. Secondly, it could profoundly alter where S1P is generated in the cell, thereby changing the proximity of S1P to the enzymes that degrade it and the receptors that use S1P as a ligand. Additionally, sphingosine kinase has recently been localized to the actin cytoskeleton, where it apparently has a direct role in regulating cytoskeletal structure [30].

It is becoming clear that localization of sphingosine kinase is key to its signaling function. The localization of sphingosine kinase to the plasma membrane is key to its oncogenic signaling capacity [28] and targeting to the phagosomal membrane appears to be key to the phagocytic capacity of macrophages [30]. Localization to the endoplasmic reticulum and the nucleus have also been reported to alter sphingosine kinase downstream signaling [18;31]. Moreover, the phosphatases which dephosphorylate S1P and the lyase that degrades it are membrane-bound enzymes with distinct intracellular localizations as well [21–23]. Generally, sphingosine kinase activity is measured in cell extracts, where the effects of localization of the enzyme on the production and metabolism of S1P are lost. Moreover the activation of sphingosine kinase is often transient. Yet the techniques for measuring acute production of S1P in intact cells are limited. We wished to establish a quick yet sensitive assay for measuring S1P production in intact cells where the effects of SK1 localization would be preserved. While previous labeling studies have successfully used tritiated sphingosine, this is cumbersome due to the low sensitivity of tritium on TLC plates and the high cost of tritiated substrates. A fluorescent derivative of sphingosine has also recently been synthesized and can label sphingosine-1-phosphate in intact cells [32]. This derivative may be useful, especially for fluorescence microscopy, but this analogue is relatively expensive and has not been extensively characterized. Here, we outline a reproducible and highly sensitive enzyme assay that quickly and inexpensively measures the acute production of sphingosine-1-phosphate in intact cells. This assay utilizes radiolabeled ATP that is exogenously added to unpermeabilized monolayers of cells. This is combined with standard lipid extraction techniques and thin layer chromatography. The high sensitivity of the assay, combined with its ease of use, offers a cost-effective approach for the study of S1P production in intact cells in which the effects of intracellular localization of the enzymes producing and metabolizing sphingosine-1-phosphate are preserved.

Materials and methods

Materials

d-erythro-[3-3H]sphingosine was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). [γ-33P]Adenosine 5′-triphosphate and [33P]orthophosphate were purchased from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA). d-erythro-Sphingosine was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody, digitonin, adenosine 5′-triphosphate, and trypan blue were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). High-glucose Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s-Medium (DMEM), L-glutamine, G418 and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from Mediatech (Herndon, VA). Other chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Plasmids and subcloning

Wild-type hSK1 was amplified from the pcDNA3-hSK1wt-FLAG clone [19] using the following primers [forward: 5′-CCCCAAGCTTATGGACTACAAGGACGACGACGACGA CAAGGATCCAGCGGGCGGCCCC-3′; reverse:5′-GCGCGGGATCCAGAACCAGATAA GGGCTCTTCTGGCGGTGGC-3′]. This cloning strategy appended HindIII and BamH1 restriction sites to hSK1 that were used to subclone hSK1 into pcDNA3 and pIRES-neo3 (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) mammalian expression vectors. At the same time, an N-terminal FLAG epitope tag and a C-terminal linker sequence [Lys-Ser-Gly-Ser-Gly-Ser] were added to hSK1-wt. Membrane targeted and anchored constructs of hSK1 (hSK1-PL16) were made by addition of a polyleucine tail [Lys-(Leu)16-Lys-Lys] to the linker sequence described above located at the C-terminus of hSK1-wt. Sequences of all DNA constructs were verified.

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa (human cervical carcinoma cells; ATCC CCL-2.2) and Hek293 (human embryonic kidney cells; ATCC CRL-1573) cells were maintained in high-glucose DMEM containing fetal bovine serum (10%), L-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (50 IU/ml), and streptomycin (50μg/ml). Stable cell lines expressing wild-type hSK1 were produced by transfecting cells for 48 hours then splitting 1:40 into 10 cm culture dishes. G418 (1 mg/ml) selection was started at this time then individual colonies were screened for SK1 activity using an in vitro enzyme assay as described below. For in situ enzyme assays utilizing transiently transfected cells, HeLa cells were plated in 48-well culture plates at 6 × 104 cells/well in complete DMEM overnight. The next day, cells were transfected with 0.4 μg plasmid DNA and 0.5 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per well according to manufacturers instructions. All transfections were carried out in antibiotic-free DMEM.

In vitro SK1 activity assay

HeLa cells transfected with vector, hSK1-wt or hSK1-PL16 were collected by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes followed by washing once in PBS and pelleting again. Cells were lysed using multiple passes through a 26-gauge needle in lysis buffer [150 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 2 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.0), and 1X complete protease inhibitor (Roche)]. Total protein concentration of lysates was determined using Coomassie Plus Bradford Assay Reagent (Pierce). To assess SK1 activity in lysates, in vitro enzyme assays were performed essentially as previously described [33]. In brief, assays were performed by incubating 5 μg of total protein at 37°C for 30 minutes with 100μM sphingosine (in 0.5% TX-100) and 33P-ATP (1 mM; 10μCi/μL) in assay buffer [100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, and 0.5 mM 4-deoxypyridoxine] in a total volume of 100μL. The enzyme reaction was terminated and S1P extracted by the addition of 700 μL of cold chloroform/methanol/HCl (100/200/1, v/v) followed by vortexing. Phases were broken by adding 200 μL each of chloroform and 2M KCl followed by extensive vortexing and centrifugation. The lower chloroform phase was collected, dried under nitrogen then resuspended in 100 μL chloroform. Labeled S1P was isolated and quantitated by TLC as described below.

In situ SK1 activity assay

HeLa cells were plated in 48-well culture plates in complete medium overnight prior to transfection. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, medium was removed and cells were washed once with 1X PBS. Enzyme reactions were started by placing 100 μL of in situ reaction mix into each well. For each well, complete reaction mix consisted of 85 μL assay buffer [150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, and 0.5 mM 4-deoxypyridoxine], 10 μL BSA/sphingosine [1 mM d-erythro-sphingosine complexed with fatty-acid free bovine serum albumin (0.2% BSA in 1M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4)], and 5 μL ATP mix [5 μL 20 mM ATP with 1 μCi 33P-ATP]. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator for the indicated times. Enzyme reactions were quenched by adding 600 μL of ice-cold methanol/HCl (150/1, v/v) to each well and placing cells on ice for 15 minutes. The acidic methanol-cell mixture was removed from each well and placed in a microfuge tube containing 700 μL of cold chloroform. Each well was rinsed with an additional 100 μL of cold methanol/HCl (150/1, v/v) and this was added to the microfuge tube. Lipids were extracted and measured as described below. For dose-response studies, concentrations of unlabeled ATP and d-erythro-sphingosine were varied while keeping the total volume of reaction buffer in each well constant at 100 μL. Additionally, the levels of radiolabeled substrates were kept constant (1 μCi/well for 33P-ATP and 0.4 μCi/well for 3H-sphingosine).

Lipid extraction and measurement of radiolabel incorporated into S1P

At the end of each in situ enzyme assay, reactions were terminated and cells were harvested using acidic methanol and added to microfuge tubes containing cold chloroform as described above. Cellular lipids were extracted using a modified version of the method by Bligh and Dyer [34]. Briefly, phases were broken by adding 400 μL of 2M KCl to each tube, vortexing extensively, centrifuging at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes then collecting the lower chloroform phase into a clean, glass tube. Samples were dried under nitrogen then resuspended in 100 μL chloroform. Lipid samples were spotted onto TLC plates (Whatman, Silica gel 60) and resolved using 1-butanol/water/acetic acid (3/1/1, v/v) as the development system. Resolved lipids were visualized using storage phosphor screens processed on a Typhoon scanner with ImageQuant software. Radiolabeled sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) was located based on co-migration with a prepared S1P standard. Known quantities of radiolabeled ATP were spotted onto each plate to generate standard curves and levels of ATP incorporated into S1P were quantified based on these standards.

Trypan blue exclusion

For microscopy, HeLa cells were plated in Nunc chamber slides at 7 × 104 cells/well in complete media overnight. For quantitative trypan blue uptake, HeLa cells were plated in 24-well tissue culture plates at 1.2 × 105 cells/well in complete media overnight. The next day, media was replaced with in situ assay buffer (described above) and cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. During the last five minutes of incubation in assay buffer, trypan blue was added to a final concentration of 0.4% (w/v). As a positive control for trypan blue uptake, digitonin permeabilization was carried out by treating cells with 0.01% (w/v) digitonin in assay buffer that included 0.4% trypan blue for three minutes. Trypan blue was removed from all wells and cells were washed twice with cold PBS to remove excess dye. For microscopy, cells were mounted in PBS without paraformaldehyde fixation, then viewed with an inverted Olympus microscope equipped with an attached CCD camera. For quantitative trypan blue uptake, 300 μL of methanol was added to each well to extract the dye from cells. Following methanol extraction, 200 μL of methanol solution was removed from each well and transferred to a 96-well plate. Absorbance was read at 605 nm using a BioTek plate reader. Trypan blue uptake of cells exposed to in situ assay buffer was compared to levels of dye taken up by cells that were permeabilized using digitonin treatment (0.01% × 3 minutes at RT).

Results and Discussion

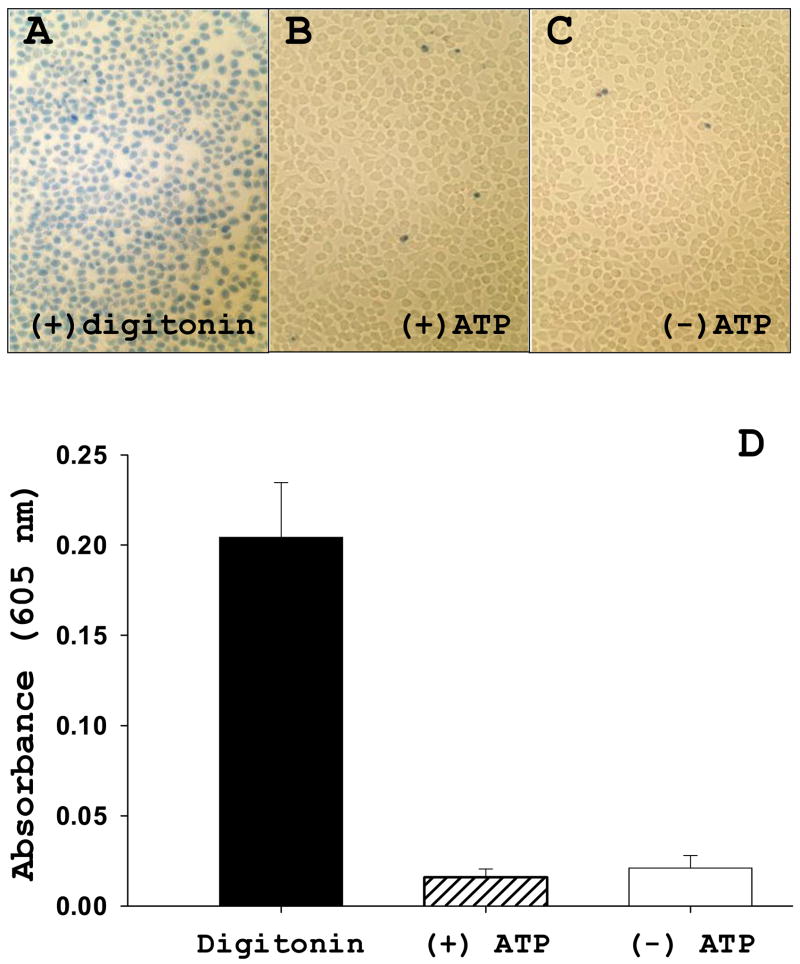

There is considerable evidence that localization of sphingosine kinase is a critical aspect of its signaling function and therefore it is important to have a system in which acute sphingosine-1-phosphate production can be measured in intact cells. While 3H-sphingosine has been used in studies of this type, this is cumbersome due to the low sensitivity and difficulty in detection of tritium on TLC plates. Therefore we examined the use of [γ-33P]ATP as a labeled substrate using low-dose digitonin permeabilization to facilitate rapid entry and equilibration of the ATP into intact cells. As a control, we included [33P]ATP incubation with non-permeabilized monolayers. Surprisingly, assay of HeLa cells overexpressing hSK1-wt revealed a substantial labeling of S1P in unpermeabilized cells. The labeling in unpermeabilized cells, in fact, exceeded labeling in the presence of digitonin (Table 1). This indicated that the ATP had gained access to sphingosine kinase in the unpermeabilized cells. Since it is widely assumed that ATP is impermeant to cells, we tested whether under our incubation conditions the cells have become permeabilized as measured by trypan blue exclusion. We found that under these incubation conditions the monolayers completely exclude trypan blue, a dye only slightly larger than ATP (Figure 1). This was assessed using microscopy (panels A–C), as well as quantitatively by solubilizing the monolayers and measuring trypan blue uptake spectrophotometrically (panel D). Treatment of the monolayers with digitonin resulted in complete permeabilization (panel A). In addition, cell morphology is indistinguishable from that of normal, growing HeLa cell monolayers.

Table 1.

In vitro enzyme activity (nmol/min/mg)

| Construct | Vehicle | Digitonin (50 μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Vector | 0.037 ± 0.004 | 0.018 ± 0.005 |

| hSK1-wt | 3.016 ± 0.144 | 0.781 ± 0.073 |

FIGURE 1. HeLa cells exposed to in situ assay conditions are still intact.

(A–C) HeLa cells were plated in Nunc chamber slides in complete media overnight. The next day, media was replaced with in situ assay buffer with or without 1 mM ATP then cells were housed at 37°C for 30 minutes. During the last 5 minutes of incubation, trypan blue (0.4%, w/v) was added to the buffer. After removing trypan blue, cells were washed twice with cold PBS then mounted in PBS for microscopy. Digitonin treatment (0.01% × 3 minutes) was used as a positive control for trypan blue uptake. (D) HeLa cells were plated in 24-well culture plates in complete media overnight. The next day, cells were treated as stated above. Following trypan blue incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS then methanol was placed on cells to extract dye. Absorbance of methanol-dye solution was read at 605 nm using BioTek plate reader. Data represent averages ± SEM (n=8) of two independent experiments.

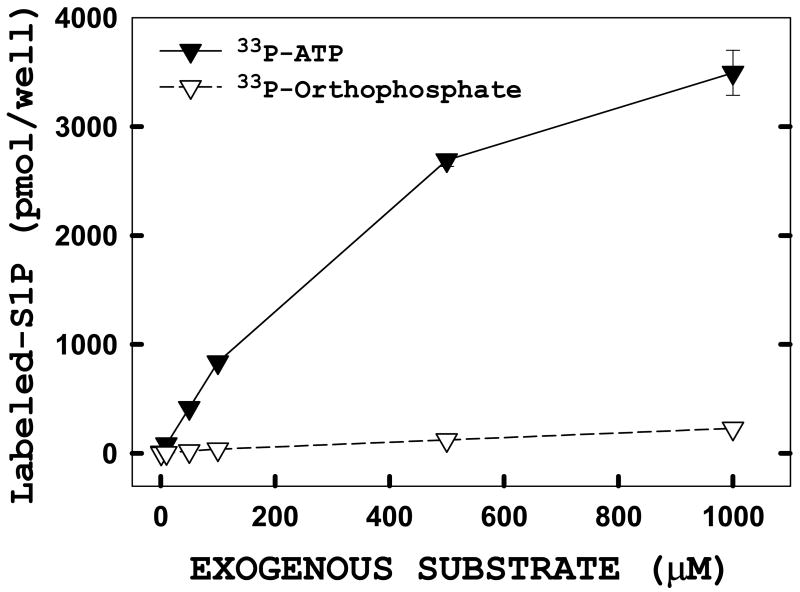

We considered the possibility that rather than intact ATP entering the cells, the labeling that we observed was due to hydrolysis of the γ-phosphate at the cell surface, and uptake of the released phosphate into the cells. To test this possibility, we compared labeling of S1P by ATP to labeling with free phosphate in intact, unpermeabilized monolayers (Figure 2). We found that ATP was utilized far more efficiently than free phosphate under these conditions. Therefore, we think it is highly unlikely that the ATP-based labeling we observe is due to release of free phosphate at the cell surface. We do not presently know the mechanism of entry of ATP into these monolayers, however the experiments outlined below strongly suggest that equilibration with intracellular pools of ATP is very rapid. Because unpermeabilized monolayers are used to assay S1P production, the intracellular distribution of sphingosine kinase is preserved and therefore we have termed this the in situ sphingosine kinase assay.

FIGURE 2. Radiolabeled orthophosphate is not an efficient substrate for the in situ assay when compared to ATP.

Adherent HeLa cells were transiently transfected with hSK1-wt. 24 hours post-transfection, the in situ enzyme assay was performed using increasing concentrations of either unlabeled ATP (filled) or orthophosphate (open). Levels of radiolabeled substrate were kept constant at 1 μCi per well. The enzyme reaction was quenched at 60 minutes then cells were harvested and lipids analyzed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data points represent averages ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

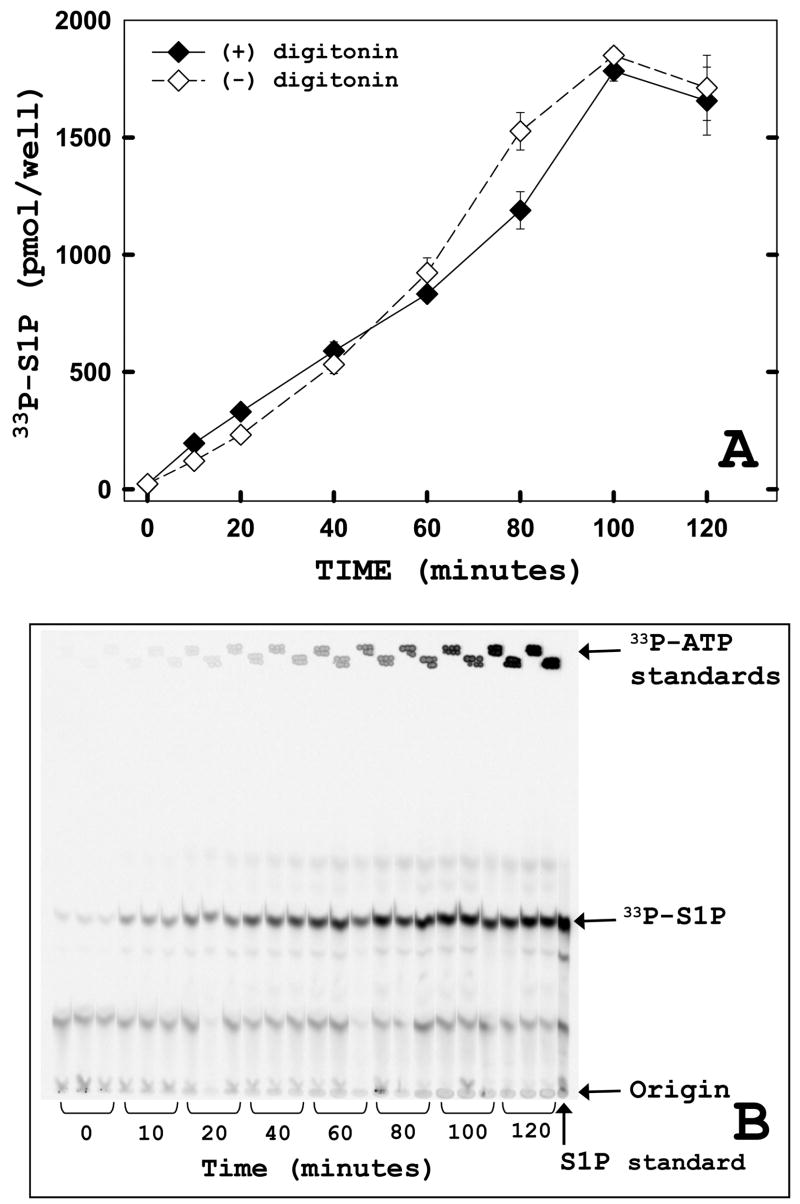

We compared the rate of ATP labeling of S1P in permeabilized and unpermeabilized cells. The fact that digitonin reduces labeling (Table 1) can be explained by the leakage of sphingosine kinase from the cells under these conditions. To eliminate this complication we generated a membrane-anchored form of sphingosine kinase by appending a tail-anchor consisting of 16 leucine residues to the carboxy terminus. This construct retains approximately the same catalytic activity as wild-type sphingosine kinase when assayed in a standard cell-free biochemical assay (activity expressed as nmol/min/mg protein: 50.6 ± 3.2 for SK1-wt vs. 47.1 ± 6.8 for SK1-PL16) and is completely membrane-bound (data not shown). When this recombinant SK1 construct was tested in cell monolayers, identical kinetics of labeled S1P generation were observed in the absence or presence of digitonin permeabilization (Figure 3). This suggests that for the in situ assay, ATP rapidly gains access to the cell interior of unpermeabilized cells, and the levels of unlabeled intracellular ATP are not significant in terms of affecting the specific activity of the label.

FIGURE 3. Digitonin permeabilization is not required for incorporation of exogenous ATP into sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P).

(A) Adherent HeLa cells were transiently transfected with a membrane-targeted and anchored hSK1 construct (PL16). 24 hours post-transfection, a time course was performed using the in situ enzyme assay in the presence (filled) or absence (open) of digitonin treatment (25 mg/ml × 20 min). Cells were harvested and lipids were analyzed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data points represent averages ± SEM of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. (B) Representative TLC plate exposure from in situ assay of PL16 transfected cells without digitonin treatment (open symbols). After harvesting lipids from cell monolayers, lipids were separated and visualized as described in “Materials and Methods.”

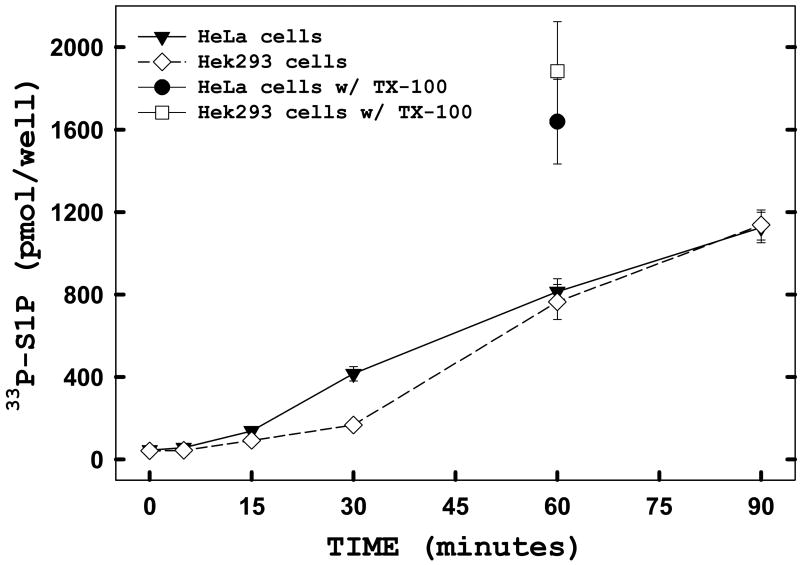

The finding that ATP was highly permeable to HeLa cells in the absence of digitonin treatment (Figure 3) was surprising to us and raised the question of whether this might be a cell type-specific phenomenon. To establish the usefulness of this assay for other cell lines, we conducted additional experiments comparing human embryonic kidney cells (Hek293) to HeLa cells. Hek293 and HeLa cells were plated overnight in complete media, then transiently transfected with wild-type hSK1 as described in ‘Materials and Methods’ twenty-four hours prior to being used for the in situ assay. As seen in Figure 4, Hek293 cells produced radiolabeled S1P as efficiently and to the same extent as HeLa cells. There appeared to be a slightly longer initial lag in the production of labeled S1P by Hek293 cells than previously seen with HeLa cells. These data indicate that this assay will prove to be useful in multiple cell lines. The level of SK activity in the intact cell assay was directly compared, in parallel wells, to activity measured in the standard Triton X-100 solubilized enzyme assay (Figure 4, floating 60 minutes time points labeled “w/TX-100”). Activity measured in this way was approximately two-fold higher than activity measured in the intact cells. This moderately increased activity may be due to enhanced access to sphingosine in the mixed-micelle assay. However this demonstrates that the majority of the cellular enzyme activity is being measured in the intact cell assay. In addition we find that the S1P produced is almost exclusively cell-associated. We routinely extract cell supernatants and monolayers together. However if the cell supernatant is extracted separately from the monolayer we find that only 1.4% of the S1P produced is found in the supernatant fraction (data not shown).

FIGURE 4. Exogenous ATP is efficiently incorporated into sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) in different cell lines.

Adherent HeLa (filled) and Hek293 (open) cells were transiently transfected with hSK1-wt. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, a time course was performed using the in situ enzyme assay in the presence of 100 μM exogenous sphingosine. To directly compare the level of SK activity measured with the in situ system to activity levels of the standard Triton X-100 in vitro system, parallel wells of transfected cells were subjected to the enzyme assay using 0.05% TX-100 to deliver the exogenous sphingosine and the assay was quenched after 60 minutes (floating points, 60 minutes). Cells were harvested and lipids were analyzed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data points represent averages ± SEM of triplicate measurements.

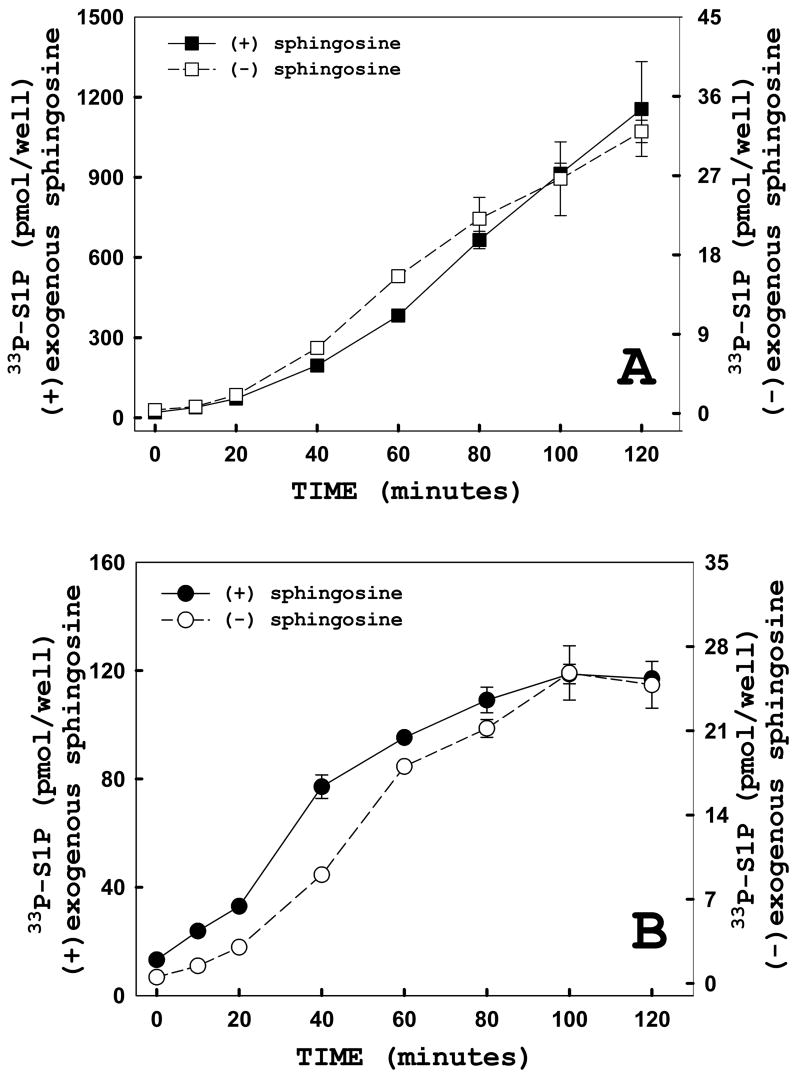

To establish the linearity of S1P production for the in situ enzyme system, adherent HeLa cells were transfected with either hSK1-wt (Figure 5A) or empty vector (Figure 5B), then subjected to time-course studies. These initial time-course studies revealed that the in situ reaction system is linear for over an hour although at times we observe a small and variable lag at the start of the assay and a plateau of varying extent after 100 minutes of labeling. Addition of exogenous sphingosine to monolayers in the in situ enzyme assay resulted in significant increases in levels of [33P]ATP incorporated into S1P (Figure 5, filled symbols). In HeLa cells overexpressing recombinant hSK1-wt, [33P]ATP incorporation into S1P was increased approximately 36-fold over levels measured in the absence of exogenous sphingosine (Figure 5A). In comparison, when measuring endogenous levels of sphingosine kinase activity, addition of sphingosine increased S1P labeling approximately 5-fold over levels measured in cells that did not receive exogenous sphingosine (Figure 5B). This is in agreement with in vitro enzyme assays. Importantly, the in situ reaction system is sensitive enough to measure levels of [33P]ATP incorporated into S1P by endogenous sphingosine kinase using endogenous levels of sphingosine (Figure 5B, right axis). Additionally, we established that in the absence of exogenous sphingosine, HeLa cells overexpressing recombinant hSK1-wt produced levels of radiolabeled S1P that were identical to levels produced by vector-transfected cells (Figure 5A vs. 5B, right axes). This is consistent with earlier observations that the concentration of sphingosine is limiting for S1P production [19].

FIGURE 5. Reaction kinetics are the same in the presence or absence of exogenous sphingosine.

Adherent HeLa cells were transiently transfected with either hSK1-wt (panel A) or empty vector (panel B) 24 hours prior to enzyme assay. Using the in situ enzyme assay, a time course was performed in the presence (filled, left axis) or absence (open, right axis) of 100 μM exogenous sphingosine. Cells were harvested and lipids were analyzed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data points represent averages ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

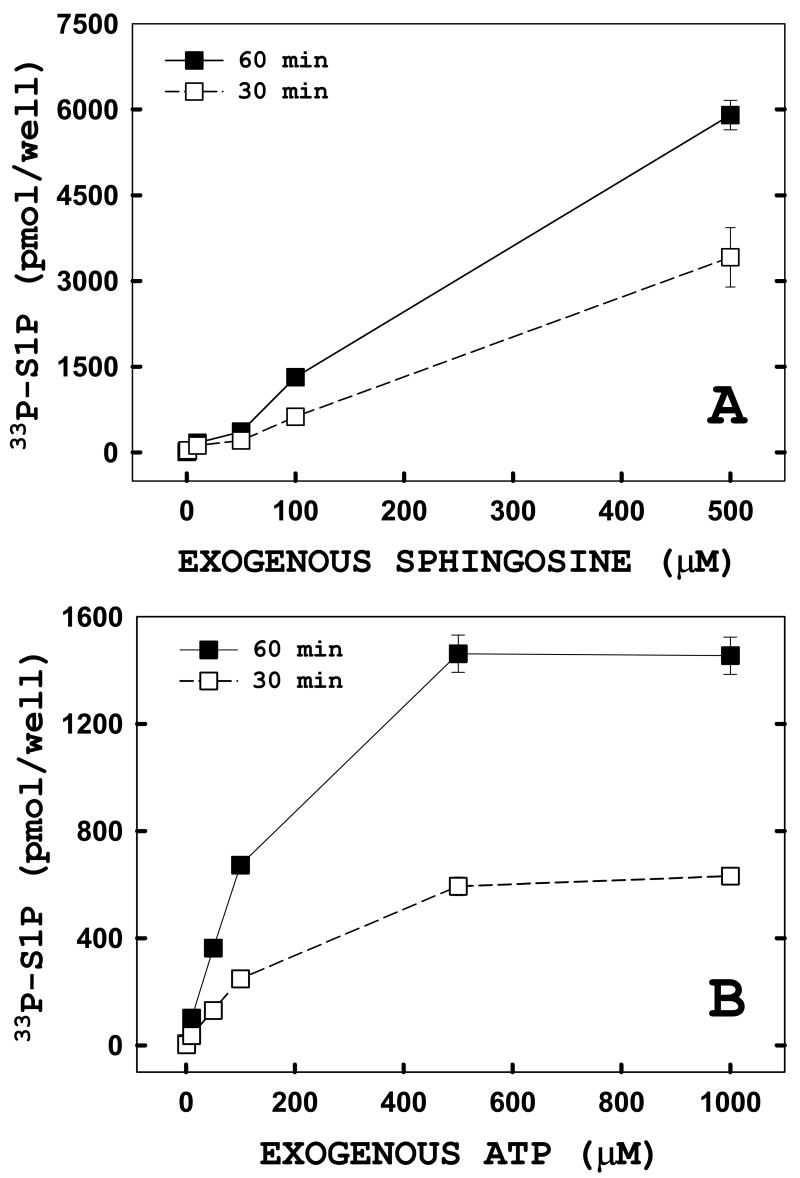

Next, we characterized the concentration dependence for the exogenous substrates used in this assay. The concentration of exogenous substrates added to monolayers of transfected HeLa cells was varied and the enzyme reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 or 60 minutes (Figure 6). Dose-dependent increases in [33P]ATP incorporation into S1P were seen for both exogenously added sphingosine (panel A) and ATP (panel B) at both time points used. The dose response to sphingosine is quite robust and linear even at the upper end of the concentration range (100–500μM). In contrast, the dose response to extracellular ATP is linear at the lower concentration ranges (0–100 μM) but levels out at the higher end of the response range (500–1000 μM). Using triplicate measurements for each ATP concentration, we calculated an apparent Km for the in situ assay of 171μM. This value contrasts to measurements made in solubilized systems, in which the Km is approximately 77μM. This discrepancy may indicate that the ATP added to cells is compartmentalized, thus reducing its access to SK1. Overall, these results establish a broad range of substrate concentrations and reaction times that can be utilized while still working within the linear parameters of the in situ enzyme assay.

FIGURE 6. Exogenous substrates are rapidly incorporated into sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

Adherent HeLa cells were transiently transfected with hSK1-wt. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, in situ enzyme assays were performed using increasing concentrations of exogenous sphingosine (panel A) or ATP (panel B). The enzyme reaction was quenched at 30 (open) or 60 (filled) minutes after which cells were harvested and lipids analyzed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Inset: enhanced view of levels of [33P]ATP incorporation into S1P measured for exogenous sphingosine concentrations ranging from 0–50 μM. Data points represent averages ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

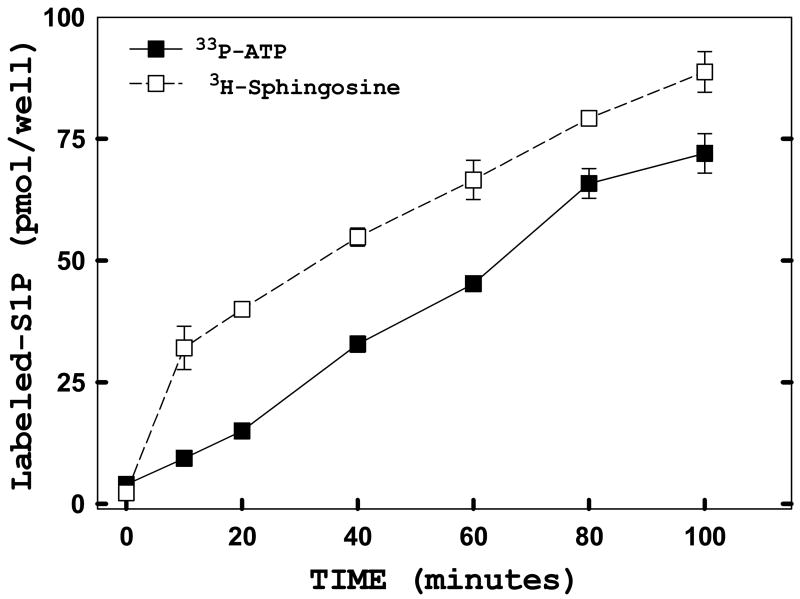

To confirm that the kinetics of SIP production as measured by [γ-33P]ATP incorporation is a valid measurement, we made the same measurements using d-erythro-[3-3H]sphingosine as opposed to radiolabeled-ATP (Figure 7). The kinetics for incorporation of [3H]sphingosine (open symbols) into S1P does not differ significantly from that seen with [33P]ATP incorporation (closed symbols). Furthermore, even though there is an initial surge in the incorporation of [3H]sphingosine into S1P at 10 minutes, the absolute levels of tritiated sphingosine incorporated into S1P do not differ significantly from levels of [33P]ATP incorporated into S1P. These results indicate relatively small intracellular pools for both substrates.

FIGURE 7. Incorporation of exogenous sphingosine and ATP into sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) occurs with similar kinetics and extents.

HeLa cells stably transfected with hSK1-wt were plated in 48-well culture plates in complete media overnight. The next day, time course studies were performed using the in situ enzyme assay. Cells were labeled with either [33P]ATP (filled) or [3H]Sphingosine (open) for the indicated times. Both time courses were carried out in the presence of 1 mM unlabeled ATP and 300 nM unlabeled sphingosine. Cells were harvested and lipids analyzed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data points represent averages ± SEM of triplicate measurements.

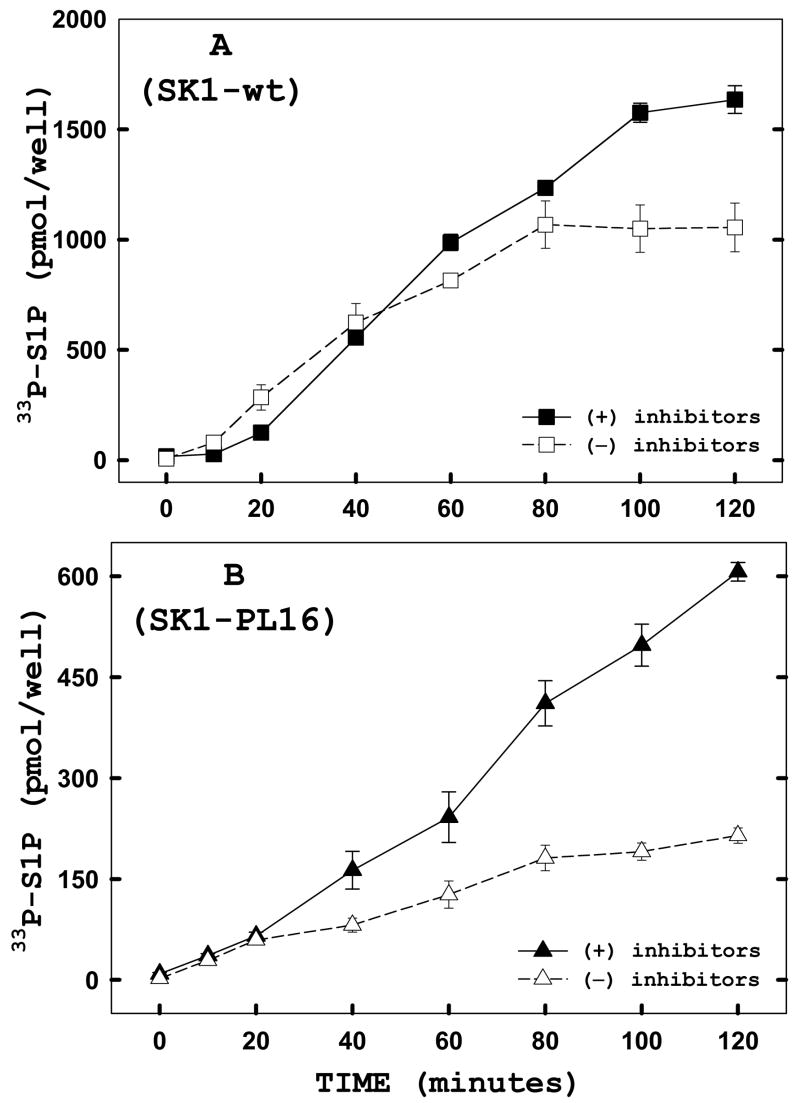

To demonstrate the usefulness of this assay we tested whether the downstream metabolism of S1P was affected by enzyme localization. The production of S1P was measured in WT-SK1-transfected or SK-PL16-transfected cells in either the absence or presence of a cocktail of phosphatase and sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase inhibitors (Figure 8). SK-PL16 appears to be predominantly bound to the endoplasmic reticulum as a consequence of the hydrophobic membrane anchor (Manuscript in preparation). It is expected that the phosphatase and lyase inhibitors will increase the cumulative production of S1P by blocking degradation. As some of the S1P phosphatases and sphingosine-1-phosphate lysase are localized to the endoplasmic reticulum[21–23], this effect would be predicted to be exaggerated in the endoplasmic reticulum-targeted SK1 construct. Indeed, while the production of S1P in WT-SK1-transfected cells was moderately increased by the inclusion of inhibitors of S1P degradation, this effect was substantially greater in the SK-PL16 transfected cells (Figure 8, panel B). These data indicate that, as expected, the production of S1P at a site close to the site of degradation reduces the net production of S1P. This experiment illustrates the utility of the intact cell assay to measure effects of S1P metabolism that depend on preservation of cellular structure and should be useful in exploring the emerging concept that SK localization is a critical element in its function.

FIGURE 8. The downstream metabolism of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is affected by localization of sphingosine kinase 1.

Adherent HeLa cells were transiently transfected with hSK1-wt (panel A) or the membrane anchored hSK1-PL16 (panel B). Twenty-four hours post-transfection, in situ enzyme assay time courses were performed in the presence (filled) or absence (open) of a cocktail of phosphatase inhibitors (10mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4) and the S1P-lyase inhibitor (0.5 mM 4- deoxypyridoxine). Twenty minutes prior to the start of each time point of the assay, the cells were preincubated in fresh media alone or media containing the cocktail of inhibitors listed above. Cells were harvested and lipids analyzed as described under “Materials and Methods.” Data points represent averages ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Conclusions

In this work, we establish the linearity and sensitivity of an in situ assay used for measuring sphingosine kinase activity in intact monolayers. Originally we were surprised that exogenous ATP was able to enter unpermeabilized cells and quickly equilibrate with intracellular pools of ATP, but by all measures the cells are intact and functional. Hla and colleagues have demonstrated that a very small proportion of SK1 can be found extracellularly[35;36]. We initially considered that the added ATP might be utilized by this extracellular SK. However a variety of evidence eliminates this as the source of the activity that we are measuring. We find only a small fraction of the total S1P produced is found in the extracellular medium. In addition, activity as measured in our intact cell assay is comparable to the total activity measured by Triton X-100 solubilization, rather than the small percentage of cellular SK that is reported to be secreted. Digitonin permeabilization decreases the activity measured rather than increasing it, as would be expected if only the small amount of extracellular SK was being measured in the intact monolayers. A membrane-anchored form of SK, which would be prevented from being secreted, has substantial activity in our assay. Furthermore, labeling with d-erythro-[3-3H]sphingosine, which is known to be cell-permeable, yields the same molar production of labeled S1P as that using 33P-ATP. This indicates that the 33P-ATP has unhindered access to intracellular SK. Based on the identical results seen with and without digitonin permeabilization of HeLa cells transfected with hSK1-PL16, a membrane-anchored enzyme, it can be concluded that the time required for ATP to equilibrate inside cells is quite short and not limiting for the assay. Nevertheless, it will be important when applying this assay to other conditions to confirm that diffences seen are due to changes in S1P metabolism rather than changes in ATP permeability. This ability of ATP to enter unpermeabilized monolayers is one aspect that makes this assay simple and inexpensive, yet sensitive enough to measure endogenous SK1 activity. The sensitivity was sufficiently high that we were able to use a 48-well plate format for most experiments providing the means to test a large number of samples and replicates. Additionally, based on the similarity of the reaction kinetics in the presence or absence of added sphingosine, we have shown that exogenous sphingosine rapidly enters cells and redistributes to sites of SK1. This assay complements methods that measure the overall mass levels of S1P, such as mass spectrometry or the radiolabeling assay constructed by Edsall and Spiegel [37]. Whereas the mass measurement methods measure the steady-state concentrations of S1P, this assay measures the rate of production of this important signaling molecule. Overall, this assay is ideal for future studies of SK1 under conditions where selective targeting of this lipid kinase occurs, to identify how localization can affect metabolism of S1P.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the James Graham Brown Cancer Center, a National Institutes of Health Center of Biomedical Research Excellence grant in Molecular Targets, NIH project grant (GB050512), and support for DLS through an American Heart Association pre-doctoral fellowship (GB060731). We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Dr. Amy Massey in the construction of hSK1-PL16.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Spiegel S, Milstien S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: an enigmatic signalling lipid. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:397–407. doi: 10.1038/nrm1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kluk MJ, Hla T. Signaling of sphingosine-1-phosphate via the S1P/EDG-family of G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:72–80. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pyne S, Pyne NJ. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling in mammalian cells. Biochem J. 2000;349:385–402. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long J, Darroch P, Wan KF, Kong KC, Ktistakis N, Pyne NJ, Pyne S. Regulation of cell survival by lipid phosphate phosphatases involves the modulation of intracellular phosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate pools. Biochem J. 2005;391:25–32. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castillo SS, Teegarden D. Ceramide Conversion to Sphingosine-1-Phosphate is Essential for Survival in C3H10T1/2 Cells. J Nutr. 2001;131:2826–2830. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kluk MJ, Hla T. Role of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor EDG-1 in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Circ Res. 2001;89:496–502. doi: 10.1161/hh1801.096338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Brocklyn JR, Lee MJ, Menzeleev R, Olivera A, Edsall L, Cuvillier O, Thomas DM, Coopman PJ, Thangada S, Liu CH, Hla T, Spiegel S. Dual actions of sphingosine-1-phosphate: extracellular through the Gi-coupled receptor Edg-1 and intracellular to regulate proliferation and survival. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:229–240. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.1.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Argraves KM, Wilkerson BA, Argraves WS, Fleming PA, Obeid LM, Drake CJ. Sphingosine-1-phosphate Signaling Promotes Critical Migratory Events in Vasculogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50580–50590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hobson JP, Rosenfeldt HM, Barak LS, Olivera A, Poulton S, Caron MG, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Role of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor EDG-1 in PDGF-induced cell motility. Science. 2001;291:1800–1803. doi: 10.1126/science.1057559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osawa Y, Banno Y, Nagaki M, Brenner DA, Naiki T, Nozawa Y, Nakashima S, Moriwaki H. TNF-alpha-induced sphingosine 1-phosphate inhibits apoptosis through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in human hepatocytes. J Immunol. 2001;167:173–180. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obeid LM, Linardic CM, Karolak LA, Hannun YA. Programmed cell death induced by ceramide. Science. 1993;259:1769–1771. doi: 10.1126/science.8456305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allende ML, Sasaki T, Kawai H, Olivera A, Mi Y, van Echten-Deckert G, Hajdu R, Rosenbach M, Keohane CA, Mandala S, Spiegel S, Proia RL. Mice Deficient in Sphingosine Kinase 1 Are Rendered Lymphopenic by FTY720. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52487–52492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwab SR, Pereira JP, Matloubian M, Xu Y, Huang Y, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte sequestration through S1P lyase inhibition and disruption of S1P gradients. Science. 2005;309:1735–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1113640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Alwani M, Wu BX, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. Bioactive sphingolipids in the modulation of the inflammatory response. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;112:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itagaki K, Hauser CJ. Sphingosine 1-Phosphate, a Diffusible Calcium Influx Factor Mediating Store-operated Calcium Entry. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27540–27547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301763200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birchwood CJ, Saba JD, Dickson RC, Cunningham KW. Calcium influx and signaling in yeast stimulated by intracellular sphingosine 1-phosphate accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11712–11718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wattenberg BW, Pitson SM, Raben DM. The sphingosine and diacylglycerol kinase superfamily of signaling kinases: localization as a key to signaling function. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1128–1139. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R600003-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maceyka M, Sankala H, Hait NC, Le Stunff H, Liu H, Toman R, Collier C, Zhang M, Satin LS, Merrill AH, Jr, Milstien S, Spiegel S. SphK1 and SphK2, Sphingosine Kinase Isoenzymes with Opposing Functions in Sphingolipid Metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37118–37129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitson SM, D’Andrea RJ, Vandeleur L, Moretti PA, Xia P, Gamble JR, Vadas MA, Wattenberg BW. Human sphingosine kinase: purification, molecular cloning and characterization of the native and recombinant enzymes. Biochem J. 2000;350(Pt 2):429–41. 429–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohta H, Yatomi Y, Sweeney EA, Hakomori S, Igarashi Y. A possible role of sphingosine in induction of apoptosis by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 1994;355:267–270. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda M, Kihara A, Igarashi Y. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase SPL is an endoplasmic reticulum-resident, integral membrane protein with the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate binding domain exposed to the cytosol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Stunff H, Galve-Roperh I, Peterson C, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphohydrolase in regulation of sphingolipid metabolism and apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:1039–1049. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Stunff H, Peterson C, Liu H, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate and lipid phosphohydrolases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) -Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2002;1582:8–17. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mastrandrea LD, Sessanna SM, Laychock SG. Sphingosine Kinase Activity and Sphingosine-1 Phosphate Production in Rat Pancreatic Islets and INS-1 Cells: Response to Cytokines. Diabetes. 2005;54:1429–1436. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia P, Wang L, Moretti PA, Albanese N, Chai F, Pitson SM, D’Andrea RJ, Gamble JR, Vadas MA. Sphingosine kinase interacts with TRAF2 and dissects tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7996–8003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shu X, Wu W, Mosteller RD, Broek D. Sphingosine kinase mediates vascular endothelial growth factor-induced activation of ras and mitogen-activated protein kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7758–7768. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7758-7768.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitson SM, Moretti PA, Zebol JR, Xia P, Gamble JR, Vadas MA, D’Andrea RJ, Wattenberg BW. Expression of a catalytically inactive sphingosine kinase mutant blocks agonist-induced sphingosine kinase activation. A dominant-negative sphingosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33945–33950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitson SM, Xia P, Leclercq TM, Moretti PA, Zebol JR, Lynn HE, Wattenberg BW, Vadas MA. Phosphorylation-dependent translocation of sphingosine kinase to the plasma membrane drives its oncogenic signalling. J Exp Med. 2005;201:49–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pitson SM, Moretti PAB, Zebol JR, Lynn HE, Xia P, Vadas MA, Wattenberg BW. Activation of sphingosine kinase 1 by ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2003;22:5491–5500. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kusner DJ, Thompson CR, Melrose NA, Pitson SM, Obeid LM, Iyer SS. The localization and activity of sphingosine kinase 1 are coordinately-regulated with actin cytoskeletal dynamics in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2007:M700193200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Igarashi N, Okada T, Hayashi S, Fujita T, Jahangeer S, Nakamura Si. Sphingosine Kinase 2 Is a Nuclear Protein and Inhibits DNA Synthesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46832–46839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hakogi T, Shigenari T, Katsumura S, Sano T, Kohno T, Igarashi Y. Synthesis of fluorescence-Labeled sphingosine and sphingosine 1-phosphate; effective tools for sphingosine and sphingosine 1-phosphate behavior. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2003;13:661–664. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00999-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olivera A, Kohama T, Tu Z, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Purification and Characterization of Rat Kidney Sphingosine Kinase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12576–12583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ancellin N, Colmont C, Su J, Li Q, Mittereder N, Chae SS, Stefansson S, Liau G, Hla T. Extracellular Export of Sphingosine Kinase-1 Enzyme. SPHINGOSINE 1-PHOSPHATE GENERATION AND THE INDUCTION OF ANGIOGENIC VASCULAR MATURATION. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:6667–6675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkataraman K, Thangada S, Michaud J, Oo ML, Ai Y, Lee YM, Wu M, Parikh NS, Khan F, Proia RL, Hla T. Extracellular export of sphingosine kinase-1a contributes to the vascular S1P gradient. Biochem J. 2006;397:461–471. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edsall LC, Spiegel S. Enzymatic measurement of sphingosine 1-phosphate. Anal Biochem. 1999;272:80–86. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]