Abstract

Purpose

To compare optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) imaging methods to discriminate eyes with early glaucoma from normal eyes.

Design

Retrospective, cross-sectional study.

Methods

Setting: Tertiary care academic glaucoma center. Ninety-two eyes of 92 subjects (46 with early perimetric open-angle glaucoma and 46 controls) were studied. Diagnostic performance of optical coherence tomography (StratusOCT), scanning laser polarimetry (GDx-VCC), confocal laser ophthalmoscopy (Heidelberg Retinal Tomograph III), and qualitative assessment of stereoscopic optic disc photographs were compared. Outcome measures were areas under receiver operator characteristic curves (AUC) and sensitivities at fixed specificities. Classification and Regression Trees (CART) analysis was used to evaluate combinations of quantitative parameters.

Results

The average (±SD) visual field mean deviation for glaucomatous eyes was −4.0±2.5 dB. Parameters with largest AUCs (±SE) were: average RNFL thickness for StratusOCT (0.96±0.02), nerve fiber indicator for GDx-VCC (0.92±0.03), FSM discriminant function for HRT III (0.91±0.03), and 0.97±0.02 for disc photograph evaluation. At 95% specificity, sensitivity of disc photograph evaluation (90%) was greater than GDx-VCC (p=0.05) and HRT III (p=0.002), but not significantly different than that of StratusOCT (p>0.05). Combination of StratusOCT average RNFL thickness and HRT III cup/disc area with CART produced a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 96%

Conclusions

StratusOCT, GDx-VCC, and HRT III performed as well as, but not better than, qualitative evaluation of optic disc stereophotographs for detection of early perimetric glaucoma. The combination of StratusOCT average RNFL thickness and HRT III cup/disc area ratio provided a high diagnostic precision.

Introduction

Structural changes of the optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer often precede visual field defects measured with standard achromatic perimetry in early glaucoma.1–6 Recognizing these morphological abnormalities is clinically important for the early diagnosis of the disease. In recent years, optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer imaging techniques have been increasingly used in clinical practice. Studies with previous versions of optical coherence tomography, confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and scanning laser polarimetry showed no significant difference between these technologies and evaluation of the optic nerve head by expert observers.7–8 More advanced versions of the same instruments and their performance relative to clinical assessment of the optic disc is examined here. This issue is important both from clinical and economic standpoints. Use of the new quantitative instruments without adequate validation could lead to improper management decisions. The purpose of the present study is to compare the ability of four currently used optic disc and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) imaging methods to discriminate eyes with early, reproducible glaucomatous visual field loss from healthy eyes.

Methods

The authors reviewed the clinical database of the Glaucoma Division at Jules Stein Eye Institute (University of California Los Angeles) for patients who underwent visual field testing and optic disc imaging with optical coherence tomography, scanning laser ophthalmoscopy, scanning laser polarimetry, and stereoscopic optic disc photographs at the same visit between April 2003 and April 2006. Subjects with poor quality imaging or unreliable visual fields were excluded. One eye each of forty-six patients with open-angle glaucoma and 46 normal controls older than 40 years of age were enrolled in this cross-sectional observational study. All eyes were required to have visual acuity equal to or greater than 20/40 and ametropia less than or equal to 5 D (spherical equivalent). Glaucomatous eyes had open angles, confirmed early defects on white-on-white automated perimetry and no history of other ocular diseases. One eye of each patient was randomly selected when both eyes fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Normal subjects were recruited among staff, patients’ spouses, and volunteers; they had a normal eye exam including a normal optic disc, intraocular pressure less than 21 mmHg, no history of ocular surgery or trauma, and a normal achromatic visual field. Normal subjects were matched with glaucomatous patients for age, gender, and ethnicity.

Visual field testing

Visual field testing was performed with the Humphrey Field Analyzer 750 (Allergan Humphrey, San Leandro, CA). Achromatic, standard 24-2 Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm visual fields were obtained. Only patients with reliable fields (fixation loss rate ≤ 33%; false positive and negative rates ≤ 20%) were included. Glaucoma patients included in the study had a mean deviation (MD) > − 8 dB, a Glaucoma Hemifield Test (GHT) outside normal limits, and a pattern standard deviation (PSD) with p < 0.05, all confirmed on two consecutive visual fields. A normal visual field was defined as one having a GHT within normal limits and a PSD with a p > 0.05 on two consecutive examinations.

Imaging methods

The StratusOCT Fast Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness algorithm was used to evaluate parapapillary RNFL thickness. Three images are automatically obtained for each eye. Each image consists of 256 A-scans along a circular ring (3.4 mm in diameter) around the optic disc. Only well centered and focused images with > 90% good quality A scans and a signal-to-noise ratio > 25 dB were included (Zeiss StratusOCT Model 3000 User Manual, PN 55153-1-Rev. A 12/02, pages 6–13). Data were exported to a personal computer and the three measurements obtained for each eye were averaged; left eye data was automatically converted into right eye format during the export procedure. The parameters calculated by the StratusOCT software (version 4.0) and evaluated in this study were: average RNFL thickness; RNFL thickness in each quadrant (superior, inferior, nasal and temporal); RNFL thickness in each of the 12 clock-hour sectors; maximum RNFL thickness in the superior and inferior quadrants (Smax and Imax, respectively); the difference between the thickest and thinnest measured points (Max − Min) and the following ratios: Imax/Smax, Smax/Imax, Smax/temporal average RNFL thickness (Tavg), Imax/Tavg, Smax/nasal average RNFL thickness (Navg). The signal strength, a measure of image quality, was also recorded.

Scanning laser polarimetry with variable corneal compensation, GDx-VCC, (Laser Diagnostic Technologies, San Diego, CA, software version 5.2.3) was used to evaluate the parapapillary RNFL. The retinal nerve fiber layer thickness is measured along a calculation circle (0.4 mm in width between the 1.6 mm outer radius and 1.24 mm inner radius) centered on the optic nerve head. This circle is divided into superior (120°), inferior (120°), nasal (50°) and temporal (70°) quadrants. The parameters calculated by the GDx-VCC software and evaluated in this study are: TSNIT Average (TSNIT: temporal, superior, nasal, inferior, and temporal again, completing a circle around the optic disc), superior average, inferior average, and TSNIT Standard Deviation (TSNIT SD). TSNIT Average is the average RNFL thickness along the calculation circle.

Superior and inferior averages are the average RNFL thicknesses in the superior and inferior quadrants of the calculation circle. TSNIT SD is the standard deviation of measurements along the calculation circle. An index called the Nerve Fiber Indicator (NFI) is calculated with a neural network algorithm. It varies between 0 and 100 with 100 representing cases with the most severe glaucoma. GDx-VCC images with good alignment and fixation and a quality score of ≥ 8 for both the corneal and RNFL images were included. The image quality scores were averaged and reported. Raw data were exported to a personal computer and used for further analysis.

Confocal Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy was performed with the Heidelberg Retina Tomograph II and analyzed with HRT III software (Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). Three 15° topographic images, obtained at the same sitting, were aligned and averaged to obtain the mean topography. Only mean topographic images of good quality (standard deviation ≤ 50 μm) were included. The following parameters, as calculated with HRT III software, were examined: disc area, cup area, rim area, cup/disc area ratio, rim/disc area ratio, cup volume, rim volume, mean cup depth, maximum cup depth, height variation contour, cup shape measure, mean RNFL thickness, RNFL cross sectional area, horizontal and vertical cup/disc ratios, maximum contour elevation and depression, temporal-inferior contour line modulation (CLM), temporal-superior CLM, reference height, FSM discriminant function (Mikelberg et al.9), and the RB discriminant function. Although the HRT III has the same scanning specifications as the HRT II, the HRT III uses an expanded normative database with ethnic specific data.

Stereoscopic photographs of the optic disc (ODPs) were obtained sequentially with a fundus camera (Fundus Flash III; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) by an experienced ophthalmic photographer. The optic disc photographs were reviewed by three experienced observers (JC, KNM, and SL). The reviewers were masked to each patient’s identity, diagnosis, each other’s scores, and all other clinical data. Each ODP was graded as 1 = normal, 2 = undetermined, or 3 = glaucoma, and a cumulative score was calculated by adding the scores assigned by the three observers. Ninety-two additional ODPs belonging to subjects not included in the study (normals, subjects suspected to have glaucoma on the basis of the optic disc appearance, and individuals with early to moderate disc damage) were added to the ODP pool to minimize evaluation bias. Image quality scores were assigned to each ODP pair with regard to image clarity (1 = acceptable, 2 = good, 3 = excellent) and stereoscopic quality (1 = flat, 2 = moderate depth effect, 3 = excellent stereopsis). Only pictures with good centration and quality were included in the study.

Statistical analyses

The normality of the distribution of numeric variables was evaluated with the Wilk-Shapiro test. Normally-distributed variables were compared with the independent sample t-test. Numeric variables that were not normally distributed were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test. Receiver operator characteristic curves were used to evaluate the performance of each imaging method for discriminating glaucomatous from normal eyes. Areas under the ROC curves (AUC) were compared with the method described by DeLong.11 Specificity cutoffs of 80% and 95% were used to compare sensitivities of the best parameter (the one with the highest AUC) for each technique. Parameters with the highest sensitivities at 80% and 95% specificities were compared with McNemar’s test. The image quality for each of the four techniques was also assessed.

Classification and Regression Trees (CART) analysis (SPSS Answer Tree version 3.1; SPSS Inc., Chicago IL) was used to identify the best combination of quantitative parameters from the StratusOCT, GDx-VCC, and HRT III. Maximum tree depth was specified at 5. The minimum number of cases in parent and child nodes was set to 10 and 5, respectively. To obtain the best diagnostic precision, the Chi-squared Automatic Interaction Detection growing method with 25-fold cross-validation and an alpha equal to 0.05 for splitting and merging of tree branches was used.

Results

The average visual field MD (± SD) in the normal group was 0.1 ± 1.2 dB and − 4.0 ± 2.5 dBin the glaucoma group (p<0.001, t-test). The demographic characteristics of the study sample are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of glaucoma cases and normal controls. 1

| Normal | Glaucoma | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Eyes | 46 (50%) | 46 (50%) | |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 58.9 ± 6.8 | 61.8 ± 9.7 | 0.1* |

| Gender (F/M) | 26 (57%)/20 (43%) | 29 (63%)/17 (37%) | 0.5† |

| Ethnicity | 0.08† | ||

| Caucasian | 25 (54%) | 31 (67%) | |

| African American | 1 (2%) | 5 (11%) | |

| Hispanic | 9 (20%) | 4 (9%) | |

| Asian | 11 (24%) | 6 (13%) | |

| IOP (mmHg, mean ± SD) | 14.0 ± 2.9 | 14.7 ± 4.3 | 0.4* |

| MD (dB, mean ± SD) | 0.1 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 2.5 | < 0.001‡ |

| PSD (dB, mean ± SD) | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 2.5 | < 0.001‡ |

| Spherical Equivalent (D) | 0.4 ± 1.7 | 0.9 ± 2.1 | 0.3‡ |

Independent-sample t-test

Chi square test

Mann-Whitney U test

Optical Coherence Tomography (StratusOCT)

The mean (± SD) and median (range) of the signal strengths in normal eyes were 8.8 (± 0.73) and 8 (8 to 9) and in glaucomatous eyes were 8.5 (± 0.55) and 8 (8 to 10) (p = 0.09; t-test). StratusOCT parameters in normal and glaucomatous eyes, areas under the ROC curves, and sensitivities at fixed specificities are presented in Table 2. The three parameters with the largest areas under the ROC curves (± SE) were: average RNFL thickness (0.96 ± 0.02), inferior quadrant RNFL thickness (0.95 ± 0.02) and RNFL thickness at the inferotemporal sector 7 (0.93 ± 0.03).

Table 2.

Comparison of StratusOCT parameters areas under the Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curves in glaucomatous and normal eyes, and sensitivities at fixed specificities. Retinal nerve fiber layer thicknesses are expressed in μm.

| RNFL thickness | Glaucoma (mean ± SD) | Normal (mean ± SD) | p value | ROC ± SE | Sensitivity at 80% specificity ± SE | Sensitivity at 95% Specificity ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Thickness | 69.7 ± 12.2 | 98.0 ± 11.2 | < .001* | 0.96 ± 0.02 | 96 % ± 3 | 89 % ± 5 |

| Inferior quadrant | 80.1 ± 20.7 | 128.0 ± 17.5 | < .001* | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 91 % ± 4 | 87 % ± 5 |

| Sector 7 | 78.9 ± 32.3 | 141.9 ± 20.9 | < .001† | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 89 % ± 5 | 78 % ± 6 |

| Inferior maximum | 108.0 ± 29.9 | 163.9 ± 21.0 | < .001* | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 89 % ± 5 | 78 % ± 6 |

| Sector 6 | 86.0 ± 26.2 | 137.5 ± 24.7 | < .001† | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 85 % ± 5 | 74 % ± 7 |

| Superior quadrant | 85.6 ± 20.1 | 122.1 ± 18.6 | < .001* | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 91 % ± 4 | 54 % ± 7 |

| Superior maximum | 113.8 ± 25.6 | 153.9 ± 19.0 | < .001† | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 85 % ± 5 | 57 % ± 7 |

| Inferior average | 80.1 ± 20.7 | 116.1 ± 17.7 | < .001* | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 87 % ± 5 | 72 % ± 7 |

| Max − Min | 126.5 ± 16.9 | 92.3 ± 22.7 | < .001* | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 78 % ± 6 | 65 % ± 7 |

| Sector 11 | 90.2 ± 26.7 | 128.8 ± 25.1 | < .001* | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 87 % ± 5 | 35 % ± 7 |

| Sector 1 | 78.6 ± 20.5 | 112.0 ± 23.7 | < .001* | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 76 % ± 6 | 28 % ± 7 |

| Sector 12 | 88.1 ± 25.9 | 125.4 ± 23.4 | < .001* | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 72 % ± 7 | 46 % ± 7 |

| Superior average | 85.6 ± 20.1 | 112.7 ± 18.9 | < .001* | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 72 % ± 7 | 50 % ± 7 |

| Sector 5 | 75.3 ± 20.3 | 104.4 ± 20.6 | < .001* | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 70 % ± 7 | 57 % ± 7 |

| Sector 8 | 54.3 ± 16.9 | 77.0 ± 17.1 | < .001* | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 63 % ± 7 | 35 % ± 7 |

| Temporal quadrant | 55.3 ± 14.4 | 71.2 ± 13.5 | < .001* | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 72 % ± 7 | 30 % ± 7 |

| Sector 2 | 67.2 ± 18.1 | 89.4 ± 21.3 | < .001* | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 57 % ± 7 | 37 % ± 7 |

| Nasal quadrant | 57.9 ± 13.2 | 70.8 ± 16.1 | < .001† | 0.74 ± 0.05 | 52 % ± 7 | 35 % ± 7 |

| Sector 10 | 64.6 ± 20.9 | 81.7 ± 18.4 | < .001* | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 65 % ± 7 | 33 % ± 7 |

| Sector 9 | 47.1 ± 14.7 | 55.2 ± 11.0 | .004* | 0.69 ± 0.06 | 54% ± 7 | 33% ± 7 |

| Sector 4 | 57.0 ± 15.6 | 66.5 ± 18.1 | .007† | 0.66 ± 0.06 | 44% ± 7 | 22% ± 6 |

| Sector 3 | 49.4 ± 13.1 | 56.8 ± 14.4 | .008† | 0.66 ± 0.06 | 35% ± 7 | 20% ± 6 |

| Smax/Imax | 1.12 ± 0.36 | 0.95 ± 0.13 | .008† | 0.66 ± 0.06 | 50% ± 7 | 35% ± 7 |

| Imax/Smax | 0.99 ± 0.37 | 1.08 ± 0.16 | .008† | 0.66 ± 0.06 | 50% ± 7 | 35% ± 7 |

| Imax/Tavg | 2.05 ± 0.65 | 2.38 ± 0.53 | .010* | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 54% ± 7 | 41% ± 7 |

| Smax/Navg | 2.02 ± 0.48 | 2.26 ± 0.48 | .020* | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 44% ± 7 | 26% ± 7 |

| Smax/Tavg | 2.15 ± 0.57 | 2.22 ± 0.42 | .494* | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 33% ± 7 | 20% ± 6 |

Independent-sample t-test

Mann-Whitney U test

RNFL: retinal nerve fiber layer; Smax: superior quadrant maximum thickness; Imax: inferior quadrant maximum thickness; Tavg: temporal quadrant average thickness; Navg: nasal quadrant average thickness; Max − Min: maximum thickness – minimum thickness.

Scanning Laser Polarimeter (GDx-VCC)

The mean (± SD) and median (range) of image quality scores for GDx-VCC in normal eyes were 8.8 (± 0.7) and 9 (8 to 9) and in glaucomatous eyes were 8.5 (± 0.5) and 8 (8 to 10) (p = 0.09; t-test). GDx-VCC parameters in normal and glaucomatous eyes, areas under the ROC curves, and sensitivities at fixed specificities are presented in Table 3. All parameters were significantly different in the two subject groups (p < 0.001). The three parameters with the largest areas under the ROC curves (± SE) were: NFI (0.92 ± 0.03), superior average RNFL thickness (0.88 ± 0.04), and TSNIT Standard Deviation (0.85 ± 0.04).

Table 3.

Parameters from Scanning Laser Polarimetry with variable corneal compensation (GDx-VCC) in glaucomatous and normal eyes, areas under the Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curves, and sensitivities at fixed specificities. Retinal nerve fiber layer thicknesses are in μm.

| Parameter | Glaucoma (mean ± SD) | Normal (mean ± SD) | p value | ROC ± SE | Sensitivity at 80% specificity ± SE | Sensitivity at 95% specificity ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFI | 51.6 ± 20.9 | 19.2 ± 8.2 | < .001† | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 89% ± 5 | 78% ± 6 |

| Superior average | 50.2 ± 10.4 | 65.9 ± 7.9 | < .001* | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 85% ± 5 | 54% ± 7 |

| TSNIT SD | 14.9 ± 4.0 | 21.3 ± 4.7 | < .001* | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 67% ± 7 | 54% ± 7 |

| Inferior average | 49.5 ± 13.0 | 64.8 ± 8.7 | < .001* | 0.84 ± 0.05 | 76% ± 6 | 59% ± 7 |

| TSNIT average | 44.6 ± 9.7 | 55.1 ± 5.9 | < .001* | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 80% ± 6 | 63% ± 7 |

Independent sample t-test

Mann-Whitney U test

NFI: Nerve Fiber Indicator. TSNIT: temporal-superior-nasal-inferior-temporal. SD: Standard Deviation.

Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscope (HRT III)

The mean (± SD) and median (range) of standard deviation of image measurements (a quality measure for HRT III) in normal eyes were 19.2 (± 12.3) microns and 16.5 microns (3 to 10) and in glaucomatous eyes were 14.6 (± 4.6) microns and 13.5 microns (9 to 29) (p < 0.001; t-test). Table 4 shows the HRT III parameters and the FSM discriminant function in normal and glaucomatous eyes, areas under the ROC curves, and sensitivities at fixed specificities. All parameters, except CLM temporal-superior, Disc Area, Height Variation Contour, and Reference Height, were statistically different in the two groups (p < 0.001). The three parameters with the largest areas under the ROC curves (± SE) were: FSM discriminant function (0.93 ± 0.03), cup/disc area ratio (0.91 ± 0.03), and rim/disc area ratio (0.91 ± 0.03).

Table 4.

Heidelberg Retinal Tomograph III parameters in glaucomatous and normal eyes, areas under the Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curves, and sensitivities at fixed specificities.

| Parameter | Glaucoma (mean ± SD) | Normal (mean ± SD) | p value | ROC ± SE | Sensitivity at 80% specificity ± SE | Sensitivity at 95%specificity ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSM discriminant function | −1.69 ± 1.9 | 1.77 ± 1.7 | < 0.001† | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 87% ± 16 | 70% ± 13 |

| Cup/disc area ratio | 0.48 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | < 0.001† | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 83% ± 15 | 67% ± 12 |

| Rim/disc area ratio | 0.52 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | < 0.001† | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 83% ± 15 | 67% ± 12 |

| Vertical cup/disc ratio | 0.67 ± 0.2 | 0.31 ± 0.2 | < 0.001* | 0.90 ± 0.03 | 89% ± 18 | 67% ± 13 |

| Rim area (mm2) | 0.98 ± 0.3 | 1.47 ± 0.3 | < 0.001† | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 83% ± 11 | 50% ± 7 |

| Cup shape measure | −0.09 ± 0.1 | −0.2 ± 0.1 | < 0.001† | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 83% ± 7 | 33% ± 6 |

| Cup area (mm2) | 0.98 ± 0.5 | 0.39 ± 0.3 | < 0.001† | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 80% ± 10 | 50% ± 8 |

| RB discriminant function | 0.09 ± 1.1 | 1.51 ± 0.7 | < 0.001* | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 85% ± 16 | 70% ± 9 |

| Cup volume (mm3) | 0.29 ± 0.3 | 0.09 ± 0.1 | < 0.001* | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 80% ± 11 | 50% ± 10 |

| Rim volume (mm3) | 0.23 ± 0.1 | 0.41 ± 0.1 | < 0.001† | 0.84 ± 0.05 | 83% ± 13 | 61% ± 8 |

| Mean RNFL thickness (mm) | 0.18 ± 0.1 | 0.27 ± 0.1 | < 0.001* | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 80% ± 12 | 50% ± 8 |

| Mean cup depth (mm) | 0.31 ± 0.1 | 0.19 ± 0.1 | < 0.001* | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 74% ± 6 | 33% ± 5 |

| Horizontal cup/disc ratio | 0.68 ± 0.2 | 0.42 ± 0.2 | < 0.001† | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 70% ± 9 | 38% ± 8 |

| Maximum contour elevation (mm) | 0.01 ± 0.1 | −0.09 ± 0.1 | < 0.001† | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 65% ± 8 | 39% ± 8 |

| RNFL cross sectional area (mm2) | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 1.29 ± 0.3 | < 0.001† | 0.8 ± 0.05 | 76% ± 8 | 37% ± 9 |

| CLM temporal-inferior (mm) | 0.07 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | < 0.001† | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 63% ± 13 | 43% ± 13 |

| Maximum cup depth (mm) | 0.72 ± 0.2 | 0.54 ± 0.2 | < 0.001† | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 48% ± 6 | 28% ± 4 |

| Maximum contour depression (mm) | 0.44 ± 0.2 | 0.32 ± 0.1 | < 0.001† | 0.7 ± 0.05 | 48% ± 5 | 15% ± 4 |

| CLM temporal-superior (mm) | 0.16 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.03† | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 43% ± 4 | 17% ± 5 |

| Reference height (mm) | 0.39 ± 0.1 | 0.35 ± 0.1 | 0.30† | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 24% ± 2 | 4% ± 2 |

| Disc area (mm2) | 1.95 ± 0.5 | 1.86 ± 0.4 | 0.60† | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 22% ± 2 | 9% ± 2 |

| Height variation contour (mm) | 0.43 ± 0.2 | 0.41 ± 0.1 | 0.52* | 0.5 ± 0.06 | 41% ± 4 | 26% ± 3 |

Independent-sample t-test

Mann-Whitney U test

RNFL: Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer; CLM: contour line modulation.

Optic Disc Stereophotographs

The mean (±SD) scores for image clarity in normal and glaucomatous eyes were 2.13 ± 0.78 and 2.69 ± 0.62 (p < 0.001), respectively. The mean (±SD) scores for stereopsis in normal and glaucomatous eyes were 1.87 ± 0.82 and 1.91 ± 0.74 (p = 0.81). The areas under the ROC curves (± SE) for the cumulative score, and for observers 1, 2, and 3 were 0.97 ± 0.02, 0.98 ± 0.02, 0.94 ± 0.03, and 0.89 ± 0.04, respectively. The agreement among observers as measured with the kappa statistic was moderate to almost perfect on the scale developed by Landis and Koch where κ >.8 is almost perfect, .6 to .8 substantial, .4 to .6 moderate, .2 to 4 fair, and < .2 slight.10 Observer 1 and Observer 2 agreed in 76% of the cases (κ = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.47 to 0.75). Agreement between Observer 2 and Observer 3 was found in 89% of the cases (κ = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.71 to 0.92) while Observer 1 and Observer 3 agreed 74% of the time (κ = 0.58; 95% CI: 0.44 to 0.73).

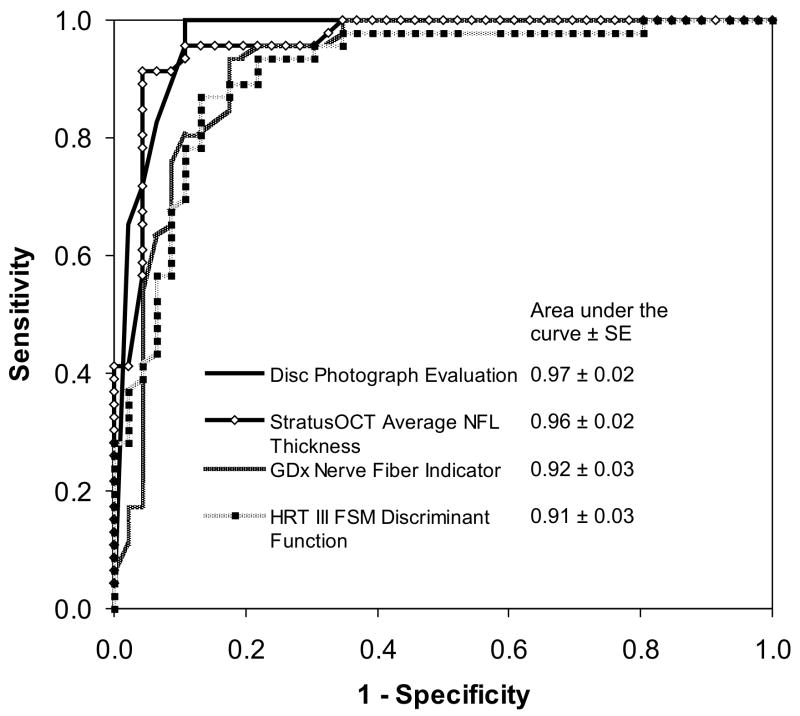

Comparison of imaging methods

No significant difference was found among areas under the ROC curves for the best parameters of the three devices (StratusOCT average RNFL thickness, GDx-VCC nerve fiber indicator, and HRT III FSM discriminant function) compared to the observers’ qualitative assessment of optic disc photographs (all p values > 0.05; DeLong test11). The corresponding ROC curves are shown in Figure 1. When parameters with the highest sensitivities at 80% specificities were compared, no significant differences were observed (p > 0.05 for all comparisons; McNemar’s test) among the four imaging methods. At 95% specificity, sensitivities were: StratusOCT average RNFL thickness 89%, GDx-VCC nerve fiber indicator 78%, HRT III FSM discriminant function 70%, and the average of three observers’ qualitative evaluation of disc photographs 90%. The sensitivity at this specificity was higher for disc photographs than GDx-VCC and HRT III parameters (p = 0.05 and p = 0.002, respectively; McNemar’s test), and was higher for StratusOCT than for HRT III (p = 0.004; McNemar’s test). There was no significant difference between StratusOCT and qualitative evaluation of disc photographs (p = 0.98; McNemar’s test).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the areas under receiver operator characteristic curves (±SE) of the best parameters from StratusOCT (average retinal nerve fiber layer thickness: 0.96 ± 0.02), GDx-VCC (Nerve Fiber Indicator: 0.92 ± 0.03), HRT III (FSM discriminant function: 0.91 ± 0.03), and the cumulative score of the three observers for disc photograph evaluation (0.97 ± 0.02).

Optimal combination of parameters

Classification and Regression Trees analysis showed StratusOCT average RNFL thickness and HRT III cup/disc area to be the best combination of quantitative parameters to distinguish between normal and glaucomatous eyes. The combination of the two parameters provided a sensitivity of 91%, a specificity of 96%, and a diagnostic precision (±SE) of 93% ± 3%. These results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Results of Classification and Regression Trees (CART) analysis for combination of the best parameters from optical coherence tomography (StratusOCT), scanning laser polarimeter (GDx-VCC), scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (HRT III). The three best parameters from each instrument were entered into the final CART analysis. With appropriate cutoff points for the StratusOCT’s average RNFL thickness and HRT III’s cup/disc area ratio, their combination provides a sensitivity of 91% (42 out of 46 glaucomatous eyes identified as such) and a specificity of 96% (44 out of 46 normal eyes classified as glaucomatous).

Discussion

This study compared the diagnostic performance of the latest versions of optical coherence tomography (StratusOCT), scanning laser polarimetry (GDx-VCC), confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (HRT III), and qualitative assessment of stereoscopic optic disc photographs in eyes with early perimetric glaucoma. The three quantitative imaging instruments performed as well as, but not better than, the evaluation of optic disc photographs by glaucoma specialists. Studies comparing previous versions of the same imaging technologies with clinical evaluation of the optic nerve did not detect significant differences in performance between the automated imaging systems and experienced clinicians.7,8 In the present investigation, the diagnostic precision of a large number of parameters was evaluated with areas under ROC curves and sensitivities at fixed specificities.

For StratusOCT, we found average retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and thickness in the inferior quadrant to have the largest areas under the ROC curve and the greatest sensitivities at 80% and at 95% specificities. Our results are consistent with a recent report by Medeiros et al. comparing the ability of various StratusOCT algorithms to differentiate between normal and glaucomatous eyes.12 In this study, among RNFL thickness, optic nerve head, and macular thickness parameters, those with the largest areas under the ROC curves were average and inferior RNFL thickness (both with an AUC value of 0.91). Budenz and associates also reported that the RFNL thickness in the inferior quadrant and average RNFL thickness were the best parameters (AUCs: 0.97 and 0.96, respectively) for discriminating healthy eyes from those with moderate glaucoma with an average MD of − 8.4.13 The RNFL thickness in the inferior quadrant was found to have the best ROC curve both with the StratusOCT and with OCT 2000 in a recent study by Bourne and colleagues who compared the two instruments.14 Previous studies with the OCT 2000 also reported that inferior quadrant RNFL thickness and average RNFL thickness best differentiated between normal and glaucomatous eyes.15–17

Rim area and cup-shape measure were found to have the largest areas under the ROC curves in two studies investigating diagnostic ability of the HRT I (Iester et al.18 and Greaney and colleagues7). Cup-to-disc area ratio and rim volume were the HRT parameters with the highest diagnostic precision in a study by Schuman et al. comparing OCT with HRT I.19 It should be noted that none of the above studies evaluated the performance of the FSM discriminant function. Although the FSM discriminant function is not provided in the HRT printout, it can be obtained from the stereometric parameters displayed on the monitor. Many investigators have shown that multivariate discriminant analysis of combinations of parameters provides better diagnostic precision compared to any single variable.20–23 With the HRT III software, we found the FSM discriminant function, cup to disc area ratio, and rim to disc area ratio to have the largest areas under the ROC curves (0.91 for all). The FSM discriminant function had the highest sensitivity (70%) at 95% specificity.

Among GDx-VCC parameters Nerve Fiber Indicator and superior average RNFL thickness had the largest areas under the ROC curves and the highest sensitivities at 80% and 95% specificities. These results are consistent with those reported by Reus and Lemij.24 They evaluated the ability of GDx-VCC to discriminate normal eyes from those with moderately advanced glaucomatous visual field defects (average MD: − 8.5). The NFI and superior average RNFL thickness had the largest area under the ROC curve in their study (0.98 and 0.94, respectively). The higher diagnostic accuracy reported in the above study may be attributed to the more advanced stage of glaucoma. Our results are also in line with those obtained by Colen et al.25 who described the NFI as the most accurate of all the GDx parameters (area under the ROC curve 0.90) and to those of Medeiros et al. who used the GDx-VCC to discriminate normal eyes from those with progressive optic disc change.26 The NFI was the best parameter from the GDx-VCC for discrimination of healthy eyes from eyes that demonstrated progressive optic disc change in that study (area under the ROC 0.92).27,28 Another study comparing the GDx-VCC and the older version of the GDx with fixed corneal compensation reported similar findings and showed that GDx performance has improved after the introduction of variable corneal compensation.29

Medeiros and associates30 compared the ability of StratusOCT, GDx-VCC, and HRT II to discriminate between normal and glaucomatous eyes. They found these parameters to have the largest areas under the ROC curve: inferior and average RNFL thickness for StratusOCT (AUCs: 0.92 and 0.91, respectively); the RB and FSM discriminant functions and linear cup/disc ratio for HRT II (AUCs: 0.86, 0.83, and 0.83, respectively); and NFI, inferior normalized area, and TSNIT average for GDx-VCC (AUCs: 0.91, 0.86, and 0.85, respectively). These results are similar to ours and no significant difference among the largest areas under the ROC curves was found among the different imaging modalities in both investigations. Statistically significant differences in sensitivities at 80% specificities were reported by Medeiros, where OCT (inferior RNFL thickness) and GDx (NFI) performed significantly better than HRT (FSM discriminant function).

A recent study of StratusOCT, GDx-VCC, HRT II, and disc stereophotograph grading by Girkin et al.31 showed qualitative assessment of the disc to be the parameter with the largest area under the ROC curve (0.90) and with the highest sensitivity (77%) at 80% specificity. We compared StratusOCT, GDx-VCC, and HRT III with clinical evaluation of stereoscopic optic disc photographs to distinguish between healthy eyes and eyes with early to moderately advanced perimetric glaucoma. Qualitative evaluation of optic disc photographs by experienced observers performed as well as any of the three quantitative imaging instruments. The diagnostic accuracy of qualitative methods depends to a large extent on the observer’s experience; therefore, the results may be different in other clinical settings and with other observers.

Various possible combinations of quantitative parameters were explored with Classification and Regression Trees analysis. The combination of StratusOCT average RNFL thickness and HRT III cup/disc area ratio was found to perform best among the quantitative parameters with a cross-validated diagnostic precision of 93%. The classification tree in Figure 2 shows that appropriate cutoffs for StratusOCT’s average RNFL thickness and HRT III’s cup/disc area ratio provided a sensitivity of 91% (42 out of 46 glaucomatous eyes identified as such) and a specificity of 96% (44 out of 46 normal eyes classified as normal). If the above sensitivity and specificity values are reproduced in subsequent studies, a reasonable method for glaucoma screening could be developed based on such a combination of parameters. However, further studies are necessary to validate the effectiveness of this approach. A similar approach was used in the past by Magacho et al 31 who reported similar findings using multivariate dicriminant formulas to combine quantitative parameters from GDx and TopSS (Topographic Scanning System formerly manufactured by Diagnostic Laser Technologies). In view of the high performance of the techniques investigated, very large study samples may be necessary to provide the power to detect small but statistically significant differences among the techniques. Such small differences, however, may not be clinically relevant.

In conclusion, we studied the diagnostic performance of qualitative evaluation of stereoscopic optic disc photographs by glaucoma specialists and contemporary versions of three quantitative imaging techniques (StratusOCT, GDx-VCC, and HRT III) in patients with early to moderate perimetric glaucoma. Each of the quantitative imaging techniques independently performed as well as, but not better than, evaluation of stereophotographs by experienced clinicians. However, clinical assessment of optic disc photos is largely influenced by the examiner’s experience and results may vary in different clinical settings. Among the quantitative techniques, StratusOCT was more sensitive for detection of glaucoma at high specificity (95%) than was HRT III. The best categorization of patients was obtained with a combination of the quantitative parameters StratusOpCT, average RNFL thickness, and HRT III cup/disc area ratio, where the values for sensitivity (91%) and specificity (96%) approach those required for successful screening of early perimetric glaucoma.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Supported in part by a Research to Prevent Blindness Physician Scientist Award (JC) and NIH grant R01-EY12738.

Financial Discolures: The authors do not have any commercial or proprietary interest in any of the products or companies cited in this manuscript. Likewise, they have no financial interest and have not received payment as a consultant, reviewer, or evaluator from any of the companies mentioned in the manuscript.

Contribution of Authors: Design and conduct of the study (FB, KNM, JC); data collection and management (FB, DR, NL); data analysis and interpretation (FB, KNM, SKL, JC); manuscript preparation and review (FB, DR, KNM, JC).

Statement about conformity with Author Information: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California Los Angeles and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient provided written informed consent for inclusion in the study.

The Authors would like to acknowledge invaluable assistance of Jeffrey A. Gornbein PhD (Department of Biomathematics, UCLA School of Medicine) with regard to statistical computing.

Footnotes

First author contact information: Federico Badalà, MD, Glaucoma Division, Jules Stein Eye Institute, 100 Stein Plaza, Los Angeles CA 90095. Phone: 310-948-0412 Fax: 310-206-7773 Email: febadal@yahoo.com

The study population consisted of one eye each from a group of glaucomatous patients with confirmed early to moderately advanced visual field defects and one eye each from a group of normal subjects.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sommer A, Katz J, Quigley HA, et al. Clinically detectable nerve fiber atrophy precedes the onset of glaucomatous field loss. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:77–83. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080010079037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson CA, Sample PA, Zangwill LM, et al. Structure and function evaluation (SAFE): II. Comparison of optic disk and visual field characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:148–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01930-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuulonen A, Airaksinen PJ. Initial glaucomatous optic disk and retinal nerve fiber layer abnormalities and their progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111:485–90. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Airaksinen PJ, Drance SM, Douglas GR, Schulzer M, Wijsman K. Visual field and retinal nerve fiber layer comparisons in glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:205–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050020057019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:701–13. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. discussion 829–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harwerth RS, Carter-Dawson L, Shen F, Smith EL, 3rd, Crawford ML. Ganglion cell losses underlying visual field defects from experimental glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2242–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greaney MJ, Hoffman DC, Garway-Heath DF, Nakla M, Coleman AL, Caprioli J. Comparison of optic nerve imaging methods to distinguish normal eyes from those with glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:140–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Berry CC, et al. Discriminating between normal and glaucomatous eyes using the Heidelberg Retina Tomograph, GDx Nerve Fiber Analyzer, and Optical Coherence Tomograph. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:985–93. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.7.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikelberg FS, Parfitt CM, Swindale NV, Iester M. Ability of the Heidelberg retina tomograph to detect early glaucomatous visual field loss. J Glaucoma. 1995;4:242–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Vessani RM, Susanna R, Jr, Weinreb RN. Evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer, optic nerve head, and macular thickness measurements for glaucoma detection using optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budenz DL, Michael A, Chang RT, McSoley J, Katz J. Sensitivity and specificity of the StratusOCT for perimetric glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourne RR, Medeiros FA, Bowd C, Jahanbakhsh K, Zangwill LM, Weinreb RN. Comparability of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurements of optical coherence tomography instruments. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1280–5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mok KH, Lee VW, So KF. Retinal nerve fiber layer measurement by optical coherence tomography in glaucoma suspects with short-wavelength perimetry abnormalities. J Glaucoma. 2003;12:45–9. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200302000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanamori A, Nakamura M, Escano MF, Seya R, Maeda H, Negi A. Evaluation of the glaucomatous damage on retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:513–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nouri-Mahdavi K, Hoffman D, Tannenbaum DP, Law SK, Caprioli J. Identifying early glaucoma with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iester M, Mikelberg FS, Swindale NV, Drance SM. ROC analysis of Heidelberg Retina Tomograph optic disc shape measures in glaucoma. Can J Ophthalmol. 1997;32:382–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuman JS, Wollstein G, Farra T, et al. Comparison of optic nerve head measurements obtained by optical coherence tomography and confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:504–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)02093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iester M, Jonas JB, Mardin CY, Budde WM. Discriminant analysis models for early detection of glaucomatous optic disc changes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:464–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.5.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uchida H, Brigatti L, Caprioli J. Detection of structural damage from glaucoma with confocal laser image analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2393–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iester M, Mardin CY, Budde WM, Junemann AG, Hayler JK, Jonas JB. Discriminant analysis formulas of optic nerve head parameters measured by confocal scanning laser tomography. J Glaucoma. 2002;11:97–104. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200204000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iester M, Mikelberg FS, Drance SM. The effect of optic disc size on diagnostic precision with the Heidelberg retina tomograph. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:545–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reus NJ, Lemij HG. Diagnostic accuracy of the GDx VCC for glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1860–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colen TP, Tang NE, Mulder PG, Lemij HG. Sensitivity and specificity of new GDx parameters. J Glaucoma. 2004;13:28–33. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200402000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Sample PA, Weinreb RN. Use of progressive glaucomatous optic disk change as the reference standard for evaluation of diagnostic tests in glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:1010–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson PA, Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Weinreb RN. Relationship between central corneal thickness and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in ocular hypertensive patients. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:251–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammadi K, Bowd C, Weinreb RN, Medeiros FA, Sample PA, Zangwill LM. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurements with scanning laser polarimetry predict glaucomatous visual field loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:592–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinreb RN, Bowd C, Zangwill LM. Glaucoma detection using scanning laser polarimetry with variable corneal polarization compensation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:218–24. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Weinreb RN. Comparison of the GDx VCC scanning laser polarimeter, HRT II confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope, and stratus OCT optical coherence tomograph for the detection of glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:827–37. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeLeón JE, Arthur SN, McGwin G, Jr, Xie A, Monheit BE, Girkin CA. Discrimination between Glaucomatous and Nonglaucomatous Eyes Using Quantitative Imaging Devices and Subjective Optic Nerve Head Assessment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3374–80. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magacho L, Marcondes AM, Costa VP. Discrimination between normal and glaucomatous eyes with scanning laser polarimetry and optic disc topography: a preliminary report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15(3):353–9. doi: 10.1177/112067210501500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]