Abstract

Endogenous pregnane neurosteroids are allosteric modulators at γ-aminobutyric acid type-A (GABAA) receptors at nanomolar concentrations. There is direct evidence for multiple distinct neurosteroid binding sites on GABAA receptors, dependent upon subunit composition and stoichiometry. This view is supported by the biphasic kinetics of various neuroactive steroids, enantioselectivity of some neurosteroids, selective mutation studies of recombinantly expressed receptors and the selectivity of the neurosteroid antagonist (3α,5α)-17-phenylandrost-16-en-3-ol (17PA) on 5α-pregnane steroid effects on recombinant GABAA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes and native receptors in dissociated neurons. However, it is unclear whether this antagonist action is present in a mature mammalian system. The present study evaluated the antagonist activity of 17PA on neurosteroid agonists both in vivo and in vitro by examining the effects of 17PA on 5α-pregnane-induced sedation in rats, native mature GABAA receptor ion channels utilizing the chloride flux assay and further studies in recombinant α1β2γ2 receptors. The data show that 17PA preferentially inhibits 3α,5α-THP vs. alphaxalone in vivo, preferentially inhibits 3α,5α-THDOC vs. alphaxalone potentiation of GABA-mediated Cl- uptake in adult cerebral cortical synaptoneurosomes, but shows no specificity for 3α,5α-THDOC vs. alphaxalone in recombinant α1β2γ2 receptors. These data provide further evidence of the specificity of 17PA and the heterogeneity of neurosteroid recognition sites on GABAA receptors in the CNS.

Index Words: neuroactive steroids, native GABA receptors, recombinant α1β2γ2 receptors, sedation

1. Introduction

GABAA receptor Cl- channels are the principal mediators of rapid synaptic inhibition in the central nervous system (Sieghart and Sperk, 2002). Pregnane steroids have been shown to be potent modulators of GABAA receptors (for reviews see (Belelli and Lambert, 2005; Paul and Purdy, 1992). Patch-clamp electrophysiological studies have shown that the progesterone metabolite 3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one (3α,5α-THP) and the deoxycorticosterone metabolite 3α,21-dihydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one (3α,5α-THDOC) act as equipotent allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors at exceptionally low concentrations by promoting the open state of the ion channel, whilst exerting no direct effect on single channel conductance (Callachan et al., 1987; Lambert et al., 1995; Majewska et al., 1986). These neurosteroids have also been shown to act as equally efficacious allosteric modulators of mature native GABAA receptors by enhancing GABAA receptor agonist-induced 36Cl- uptake into cerebral cortical synaptoneurosomes with nanomolar potency (Belelli and Gee, 1989; Morrow et al., 1987).

There is evidence that distinct neurosteroid binding sites exist on GABAA receptors. Multiple distinct neurosteroid recognition sites on GABAA receptors have recently been identified (Hosie et al., 2006). Most GABAergic neuroactive steroids potentiate GABA actions on Cl- uptake (Morrow et al., 1990) or Cl- conductance (Puia et al., 1990) with biphasic activation curves. Additionally, the enantioselectivity of the GABAA modulatory and anesthetic properties of 3α,5α-THP, with the synthetic ent-3α,5α-THP being less potent (Wittmer et al., 1996) supports the identification of multiple steroid recognition sites.

The development of the neurosteroid antagonist (3α,5α)-17-phenylandrost-16-en-3-ol (17PA) has provided further evidence for the existence of multiple neurosteroid binding sites on GABAA receptors (Mennerick et al., 2004). 17PA has been shown to selectively antagonize the modulatory effects of 3α,5α-THP, but not 3α,5β-THP, at recombinant GABAA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes and native GABAA receptors in dissociated hippocampal neurons (Mennerick et al., 2004). These data support the notion that distinct neurosteroid binding sites may exist independently on GABAA receptors for 5α- and 5β-pregnane steroids (Mennerick et al., 2004).

While the previous electrophysiological studies of recombinant GABAA receptors have convincingly shown the direct antagonism of the GABA-modulatory effects of 5α-pregnane steroids by 17PA, the receptors studied were expressed in host cells that may possess different phosphorylation and signaling mechanisms from their neuronal counterparts. Additionally, the dissociated neurons were obtained from rats on post-natal day 1-3 and may not be expected to have mature receptors reflecting the subunit composition and stoichiometry of adult neurons (Bovolin et al., 1992). Although studies of tadpole loss of righting reflex have further supported the neurosteroid antagonist profile of 17PA in vivo, it is unknown whether similar effects would be found in mammalian systems, particularly due to differences in receptor subtype distribution, subunit expression and amino acid sequence divergence between amphibians and mammals. Therefore, it was the purpose of the present study to compare the neurosteroid antagonist activity of 17PA in vivo in a mammalian system with recombinant α1β2γ2 receptors studied in vitro. We investigated the direct administration of 17PA into the rat brain and examined its effects on neurosteroid-induced sedation, as well as examining its pharmacological action on native mature cerebral cortical GABAA receptors utilizing the chloride flux technique and recombinant α1β2γ2 receptors using patch clamp electrophysiology. We chose to study α1β2γ2 receptors since these are the most abundant receptor subtype in mammalian brain and represents greater than 50% of GABAA receptors in cerebral cortex (Kralic et al., 2002).

2. Methods

2.1 Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (N = 152, Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) purchased at approximately 250 g at the start of experiments were used as test subjects. The rats were housed individually in plastic cages and were provided access to food (Teklad, Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and water ad libitum. The illumination in the vivarium was maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700 hours) with temperature maintained at 23 °C. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted according to the “Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Research Council, 1996).

2.2 Drug Preparation

17PA was synthesized as previously described (Mennerick et al., 2004). 17PA was dissolved in a vehicle composed of 35% β-cyclodextrin (w/v) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and sterile artificial cerebrospinal fluid (125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 5 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 1.2 CaCl2·2H2O, 5 mM D-glucose, pH to 7.4 with NaOH). 3α,5α-THP and 3α,5α-THDOC were purchased from Dr. Robert Purdy, Scripps Institute, La Jolla, California, USA. 3α,5α-THP was dissolved in a vehicle composed of 20% β-cyclodextrin (w/v) and 0.9% NaCl. Alphaxalone and pregnenolone sulfate were purchased from Steraloids (Newport, RI, USA) and dissolved in a vehicle composed of 20% β-cyclodextrin (w/v) and 0.9% NaCl. For chloride flux experiments 17PA, alphaxalone, pregnenolone sulfate, 3α,5α-THP and 3α,5α-THDOC were dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide and diluted in assay buffer to a final dimethyl sulfoxide concentration of ≤ 0.4%.

2.3 Cannulae Implantation

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) prepared for aseptic surgery and secured into a stereotaxic instrument (David Kopf, Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA). Stainless steel guide cannulae (22 gauge, Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA) aimed at 1 mm dorsal of either the right or the left lateral ventricles were implanted using the following stereotaxic coordinates: -0.92 mm from bregma; ± 1.4 mm lateral from the midline; 2.4 ventral to the cortical surface (Hodge, 1994). The guide cannulae were held in place by dental resin anchored to four stainless steel screws (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA) fixed to the skull. All measurements were taken from flat skull. Rats were provided with buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg, ip) post-operatively for pain relief and allowed to recover for at least 7 days prior to the initiation of experiments.

2.4 I.C.V. Drug Administration

All rats were handled extensively prior to the initiation of i.c.v. procedures in order to reduce stress and become habituated to manipulation of the guide cannulae. Rats were placed in plastic containers to reduce movement and i.c.v. injections were performed on conscious unrestrained animals. A 28-guage injector was connected to a 10 μl glass Hamilton syringe via PE-50 catheter tubing filled with sterile de-ionized water. An air-bubble (1 μl) was drawn to the distal end of the catheter tubing to separate the 17PA or vehicle solution and the sterile de-ionized water. To ensure proper drug delivery, precise flow of the i.c.v. solution was verified by noting the movement of the air-bubble down the catheter tubing by visual inspection during each i.c.v. infusion. Obturators were removed and the sterile 28-gauge injector was inserted to a depth 1 mm beyond the end of the guide cannulae into either the left or right lateral ventricle. During each i.c.v. infusion, 17PA or vehicle was infused in a total volume of 10 μl over a 4 min period. The injector remained in place for an additional 4 min to allow for drug diffusion. New sterile obturators were inserted after removal of the injectors. Following drug diffusion, the rats were then fitted into an adjustable plastic restrainer exposing the tail and the neuroactive steroid (i.e., 3α,5α-THP or alphaxalone) was administered intravenously into the lateral tail vein. To verify correct placement of the needle and proper i.v. drug administration, a small quantity of blood was noted to ‘flash’ back into the hub of the needle. In order to minimize the number of animals needed for the in vivo sedative/hypnosis studies, all rats received consistently either 17PA or vehicle i.c.v. across multiple doses of steroid (i.e., 3α,5α-THP or alphaxalone). 10 nmoles of 17PA (10 μl of 1 mM 17PA) was the highest dose of 17PA attainable for the in vivo cannulation experiments. Preliminary experiments indicated that higher concentrations of 17PA were insoluable.

At the end of all experiments, the rats were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation followed by decapitation. Correct placement of the guide cannula was verified by infusion of 10 μl of the dye, methyl green (1%) dissolved in the i.c.v. vehicle over 4 min. There was an additional 4 min to allow for diffusion of the dye-i.c.v. vehicle followed by removal of the brain and gross sectioning through the cannula tract. Visualization of the methyl green dye on the wall of the lateral ventricle indicated correct placement of the guide cannula.

2.5 Assessment of Sedation/Hypnosis

Sedation/hypnosis was measured by loss of righting reflex. Loss of righting reflex was defined as the inability of the rats to right themselves three times when placed in a supine position during a one-min interval.

2.6 Chloride Uptake Analysis

The pharmacological actions of 17PA on native GABAA receptors were studied in a subcellular vesicle preparation (synaptoneurosomes) as previously described (Kumar et al., 2005; Morrow et al., 1990). Brains were rapidly removed following decapitation and placed into ice-cold assay buffer (20 mM Hepes, 118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 2.5 mM, CaCl2 pH 7.4 with Tris-Base). Cerebral cortices were isolated and homogenized manually in ice-cold assay buffer using a glass-glass homogenizer (5 strokes). The homogenate was brought to volume (30 ml) and filtered through three layers of 160 μm nylon mesh followed by additional filtration through a 10 μm filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The homogenate was then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 15 min followed by resuspension in 30 ml of ice-cold assay buffer and subsequent homogenization in a Teflon-glass homogenizer (3 strokes). The homogenate was further centrifuged twice more at 1000 × g before final resuspension of the synaptoneurosomal pellet in assay buffer to yield a final protein concentration of approximately 6 mg/ml. Aliquots (200 μL) of homogenate were dispensed to each assay tube and pre-incubated at 30 °C for 12 min. Muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake was initiated by the addition of 0.4 μCi 36Cl (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, England, UK) in the presence of an EC20 concentration (1.5 μM) of muscimol alone or in conjunction with 3α,5α-THDOC, alphaxalone and 17PA. The solution was vortexed and uptake was terminated after 5 seconds by addition of 4 ml of ice-cold assay buffer containing 100 μM picrotoxin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) under rapid vacuum filtration over G6 filters (Fisher Scientific, UK) using a single manifold filter apparatus (Hoeffer, San Francisco, CA, USA). Following two more picrotoxin washes, filters were allowed to dry and radioactive counts were determined by liquid scintillation spectroscopy.

2.7 Data analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. The duration of the loss of righting reflex response was measured. loss of righting reflex durations (total sleep time) for both 3α,5α-THP and alphaxalone were analyzed by a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with one between-subjects factor, i.c.v. 17PA dose, and one within-subjects factor, i.v. 3α,5α-THP or alphaxalone dose. Multiple comparison post-hoc tests were performed using Tukey’s t. In addition to total sleep time, dose-effect data for animals receiving i.c.v. 17PA or vehicle were fitted to the quantal analysis equation of the form

| (1) |

were p is percent of the population anesthetized, D is the drug dose, n is the slope factor and ED50 is the drug dose for half-maximal effect (Waud, 1972). Unpaired t-tests were performed using the i.c.v. 17PA and vehicle mean ED50 and s.e.m. estimated from the quantal analysis equation for both 3α,5α-THP and alphaxalone. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. For chloride flux experiments, data are expressed as net 36Cl- uptake or potentiation in nmole/mg of protein. The net uptake represents total chloride uptake in the absence of muscimol (basal). Potentiation represents the increase in 36Cl- over and above, but not including, that produced by muscimol stimulation. Concentration-response curves were fitted to the equation of the form

| (2) |

where E is potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake, Emax is the maximal potentiation and A is the concentration of steroid. Protein determinations were made using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

2.8 Electrophysiology

Stage V-VI oocytes were harvested from mature female Xenopus laevis (Xenopus One, Northland, MI) and were defolliculated and injected with rat α1, β2 and γ2L subunit cRNA transcribed using the mMESSAGE mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Oocytes were incubated up to 5 days at 18° C in ND96 medium containing (in mM): 96 NaCl, 1 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2 and 5 HEPES at pH 7.4, supplemented with pyruvate (5 mM), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and gentamycin (50 μg/ml). Cells were clamped at −70 mV using an OC725 two-electrode voltage-clamp amplifier (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA), and current at the end of 30 s drug applications was measured for quantification of current amplitudes. Steroids and 17PA were co-applied with GABA by gravity perfusion. Acquisition and analysis were performed with pCLAMP 9.0 (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA). Statistical differences were determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

3. Results

3.1 Loss of Righting Reflex

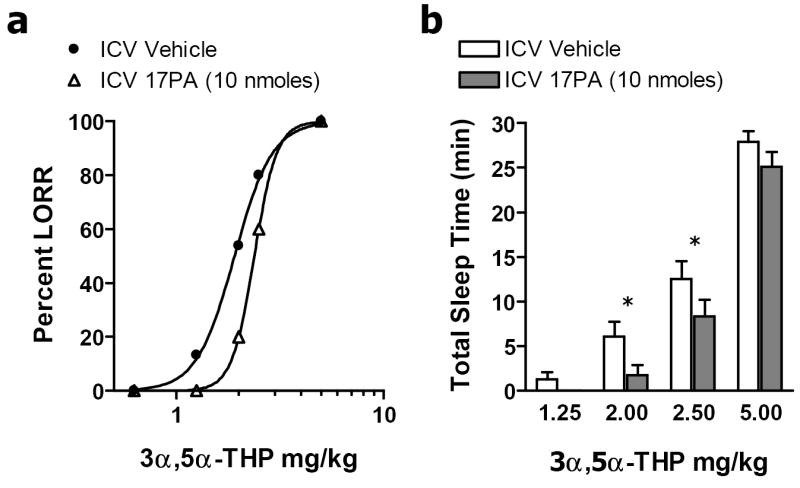

We examined whether i.c.v. administration of the putative neurosteroid antagonist 17PA could attenuate the sedative/hypnotic action of 3α,5α-THP and the synthetic neurosteroid alphaxalone. Loss of righting reflex was used as the primary measure of sedation/hypnosis. Pre-treatment with i.c.v. administration of 17PA resulted in a rightward shift in the loss of righting reflex dose-response curve, decreasing the percentage of animals (n = 15 per 17PA dose) exhibiting loss of righting reflex in response to 3α,5α-THP (0.625 – 5.0 mg/kg, i.v.). 3α,5α-THP in the presence of i.c.v. vehicle had an effective dose (ED50) of 1.91 ± 0.02 mg/kg with a slope factor of 4.8 ± 0.28, whilst 3α,5α-THP in the presence of 17PA (10 nmoles) showed a significantly higher ED50 of 2.4 ± 0.01 (t = -19.85, df = 28, P < 0.05) with a slope factor of 8.1 ± 0.12 (Fig 1). 17PA pre-treatment reduced the total sleep time induced by 3α,5α-THP (Two-way ANOVA, F = 6.9, df =1,135, P < 0.05). Additional post-hoc analyses showed that 17PA pre-treatment significantly attenuated total sleep time induced by 3α,5α-THP at 2.0 and 2.5 mg/kg (Tukey’s t, P <0.05).

Figure 1.

Effects of 17PA on 3α,5α-THP-induced loss of righting reflex (LORR). a. I.c.v. administration of the neurosteroid antagonist 17PA attenuated the sedative/hypnotic action of the physiological neurosteroid, 3α,5α-THP. Pre-treatment with 17PA (10 nmoles) induced a significant rightward shift in the percentage of animals exhibiting loss of righting reflex to intravenous administration of 3α,5α-THP (0.625 – 5.0 mg/kg). b I.c.v. administration of 17PA significantly reduced 3α,5α-THP-induced loss of righting reflex duration as revealed by a one-way repeated measures ANOVA (F = 6.9, df =1,135, P < 0.05). A Tukey’s multiple comparison post-hoc analyses showed that 17PA pre-treatment significantly attenuated loss of righting reflex time induced by 3α,5α-THP at 2.0 and 2.5 mg/kg (P <0.05).

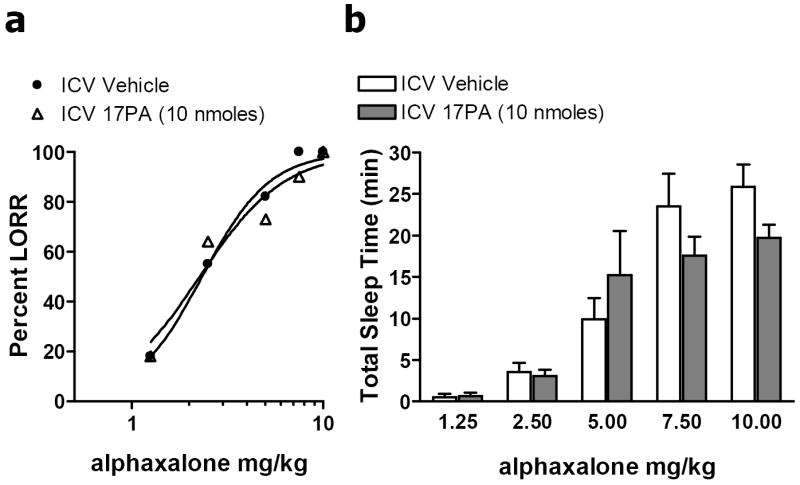

In contrast, i.c.v. administration of 17PA did not significantly alter sedative/hypnotic action of the synthetic neurosteroid, alphaxalone. Pre-treatment with 17PA (10 nmoles, n = 11) produced no significant shift in the percentage of animals exhibiting loss of righting reflex to intravenous administration of alphaxalone (1.25 – 10.0 mg/kg). Alphaxalone in the presence of i.c.v. vehicle (n = 11) produced an ED50 of 2.3 ± 0.13 (Mean ± S.E.M.), whilst pre-treatment with 17PA produced no significant change in the sedative potency of alphaxalone with an ED50 of 2.26 ± 0.30 (t = -0.2, df= 20, P = 0.844) (Fig 2). Additionally, i.c.v. administration of 17PA did not significantly reduce total sleep time under alphaxalone as revealed by a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (F = 0.58, df =1,104, P = 0.46).

Figure 2.

Effects of 17PA on alphaxalone-induced loss of righting reflex. a. I.c.v. administration of 17PA did not significantly alter sedative/hypnotic action of the synthetic neurosteroid, alphaxalone. Pre-treatment with 17PA (10 nmoles) did not produce a significant shift in the percentage of animals exhibiting loss of righting reflex to intravenous administration of alphaxalone (1.25 – 10.0 mg/kg). b. I.c.v. administration of 17PA does not significantly reduce alphaxalone-induced loss of righting reflex duration as revealed by a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (F = 0.58, df =1,104, P = 0.46).

3.2 Chloride Flux and Electrophysiology

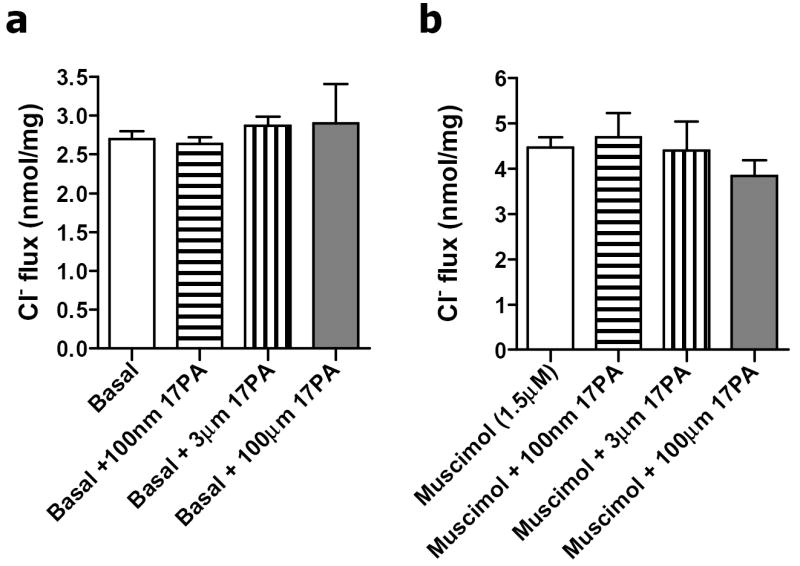

17PA (0.1 μM – 100 μM) did not significantly alter basal 36Cl- uptake in synaptoneurosomes (One-way ANOVA, F = 0.2, df = 10, p = 0.89). Additionally 17PA did not significantly alter 36Cl- uptake stimulated by muscimol (1.5 μM) (F = 0.62, df = 11, p = 0.62) demonstrating no direct antagonist action at native GABAA receptors (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of 17PA on basal or muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake. a. 17PA (0.1 μM – 100 μM) did not significantly alter basal 36Cl- uptake in synaptoneurosome preparations (One-way ANOVA, F = 0.2, df = 10, p = 0.89). b. 17PA did not significantly alter 36Cl- uptake stimulated by muscimol (1.5 μM) (F = 0.62, df = 11, p = 0.62) demonstrating no direct antagonist action at native GABAA receptors.

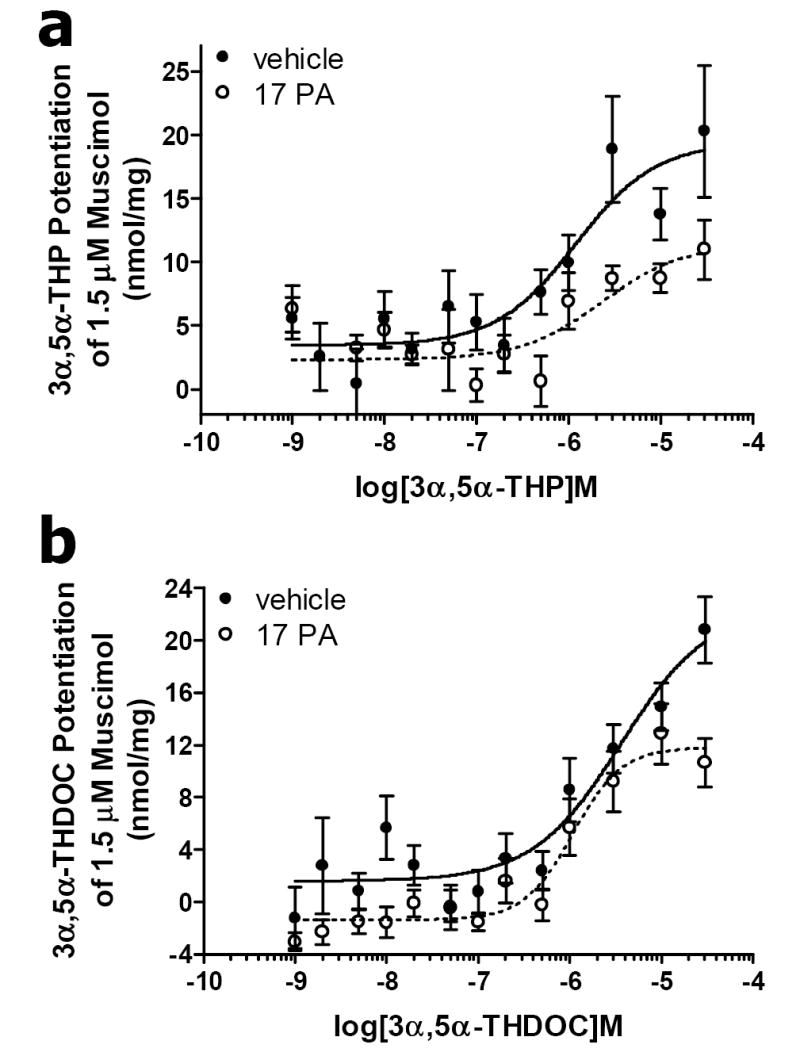

The antagonist action of 17PA on neurosteroid potentiation of muscimol induced Cl- flux was assessed across a range of doses (1nM - 30μM) for both the physiological neurosteroids, 3α,5α-THP and 3α,5α-THDOC. 17PA did not produce a significant rightward shift in the dose-response curve for 3α,5α-THP (Fig 4a). However, 17PA significantly reduced the Emax of 3α,5α-THP potentiation, (11.78 versus 19.41 nmoles/mg prot., t = 2.351, df = 16, p < 0.05). In an similar manner, 17PA did not produce a significant rightward shift in the dose-response curve for 3α,5α-THDOC (Fig 4b). However, 17PA significantly reduced the Emax of 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation, (11.81 versus 20.82 nmoles/mg prot., t = 3.24, df = 16, p < 0.01) therefore attenuating maximal 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake. Furthermore, 17PA altered the characteristics of the 3α,5α-THDOC dose-response curve, such that saturation was achieved within two orders of magnitude, consistent with binding to a single recognition site.

Figure 4.

The antagonist action of 17PA on 3α,5α-THP and 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake. a. 17PA antagonism was assessed across increasing 3α,5α-THP concentrations in rat cerebral cortical synaptoneurosomes. 17PA (open circles) did not produce a significant rightward shift in the concentration-response curve compared to vehicle (closed circles). However, 17PA significantly reduced 3α,5α-THP Emax (P < 0.05), therefore attenuating maximal 3α,5α-THP potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake. b. 17PA antagonism assessed across increasing 3α,5α-THDOC concentrations in rat cortical synaptoneurosomes. 17PA (open circles) did not produce a significant rightward shift in the concentration-response curve for 3α,5α-THDOC compared to vehicle (closed circles) but significantly reduced the Emax of 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake (P < 0.01), thus attenuating maximal 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation in the synaptoneurosome preparation.

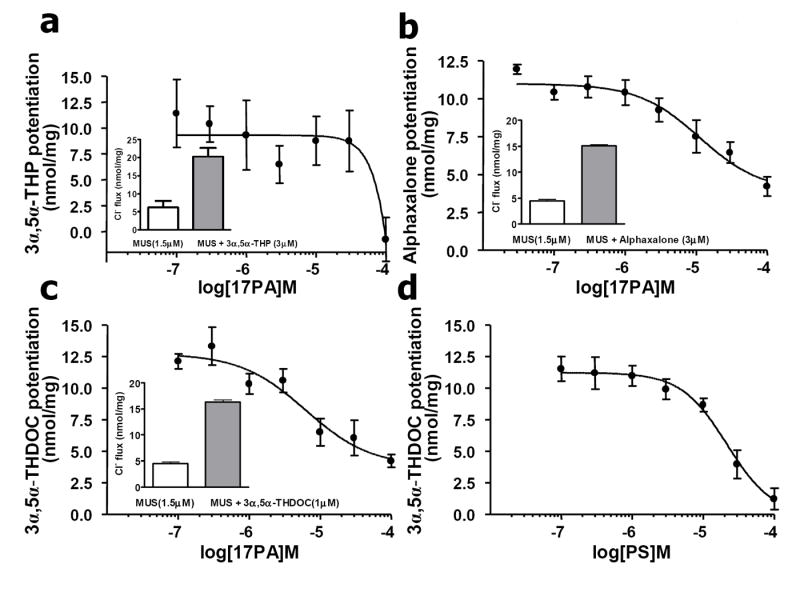

As expected, the physiological neurosteroid 3α,5α-THP (3μM) significantly potentiated muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake (t = 4.493, df = 25, P<0.0001) (Fig 5a, inset). Increasing concentrations of 17PA (0.1 μM – 100 μM) completely blocked 3α,5α-THP potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake(IC50 = 30.17 μM) (Fig 5a). There was significant potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake by the synthetic neurosteroid, alphaxalone (3 μM) (t = -29.76, df = 5, P<0.001) (Fig 5b, inset). However, 17PA only partially attenuated the alphaxalone potentiation of muscimol stimulation albeit with a greater potency comparison to 3α,5α-THP (IC50 = 11.23 μM) (Fig 5b). The neurosteroid 3α,5α-THDOC (1 μM) also significantly potentiated muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake (t = -29.42, df = 4, P<0.001) (Fig 5c, inset). However, as with alphaxalone, increasing concentrations of 17PA (0.1 μM – 100 μM) only partially attenuated 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake (IC50 = 6.08 μM) (Fig 5c). Lastly, the neurosteroid non-competitive GABA-receptor antagonist pregnenolone sulfate (0.1 μM – 100 μM) completely blocked 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation (IC50 = 21.64 μM)(Fig 5d).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the antagonist action of 17PA on 5α-reduced steroid potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake in rat cortical synaptoneurosomes. a. 3α,5α-THP (3 μM) potentiation of muscimol-stimulated (1.5 μM) 36Cl- uptake relative to basal (P<0.0001, inset panel). Note that 17PA completely blocked 3α,5α-THP potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake (IC50 = 30.17 μM). b. Synthetic neurosteroid alphaxalone (3 μM) potentiation of muscimol-stimulated (1.5 μM) 36Cl- uptake (P<0.001, inset panel). Note that 17PA partially attenuated alphaxalone potentiation of muscimol stimulation (IC50 = 11.23 μM). c. 3α,5α-THDOC (1 μM) potentiation of muscimol-stimulated (1.5 μM) 36Cl- uptake (P<0.001, inset panel). 17PA partially attenuated 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation of muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake (IC50 = 6.08 μM). d. pregnenolone sulfate inhibition of 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation (IC50 = 21.64 μM).

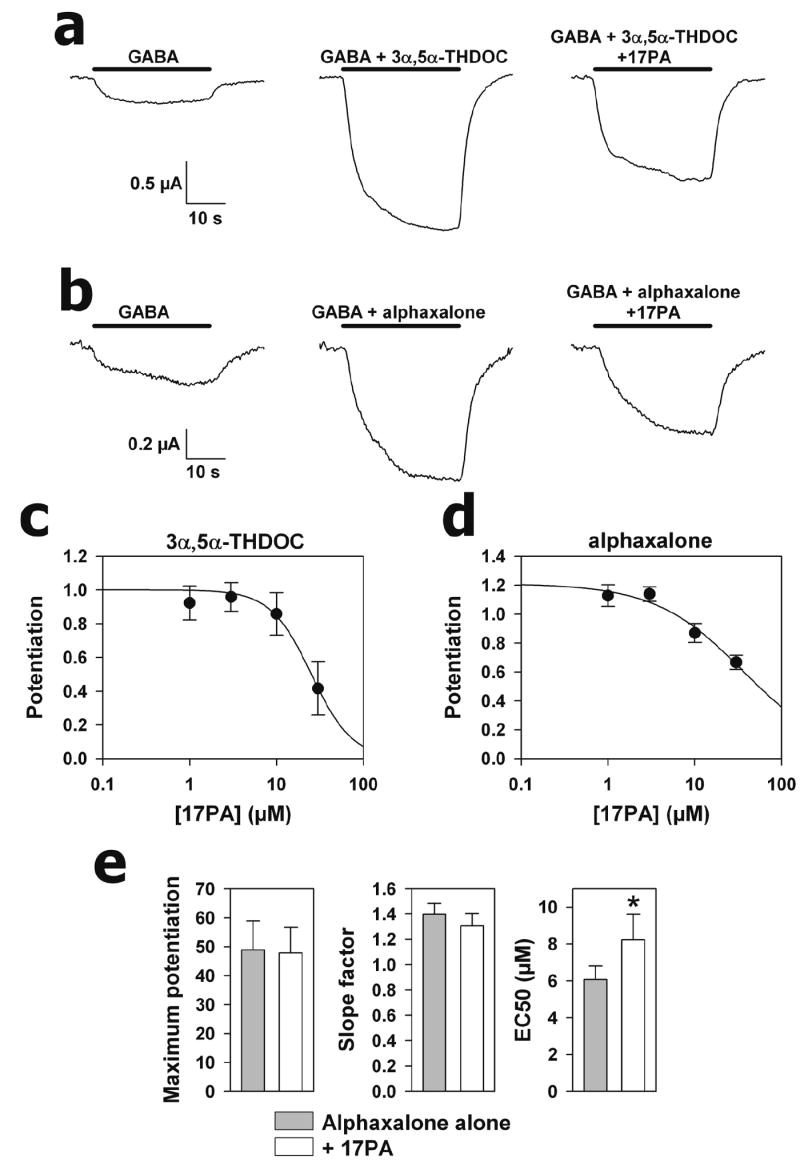

Since 17PA did not inhibit the duration of alphaxalone hypnosis, exhibited 2-fold greater antagonist potency for both the physiological neurosteroids 3α,5α-THP and 3α,5α-THDOC, completely blocked the effects of 3α,5α-THP potentiation, whilst only partially attenuated the effects of both 3α,5α-THP and 3α,5α-THDOC in the Cl- flux assay, we explored whether this observation was dependent on the subunit diversity of the mammalian preparations. The effects of 17PA on both 3α,5α-THDOC and alphaxalone potentiation of GABAA receptors were explored in recombinant α1β2γ2 receptors expressed in frog oocytes. Figure 6 shows that both 3α,5α-THDOC (0.5 μM) and alphaxalone (0.5 μM) enhanced GABA-mediated Cl- conductance to a similar extent (4.65 vs 3.55-fold increase, n = 5 and 4 oocytes respectively). 17PA (10 μM) partially inhibited the effects of both 3α,5α-THDOC and alphaxalone. These effects were not significantly different, although the trend was for a larger effect of 17PA on 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation, with a lesser concentration of 17PA needed to obtain IC50 on 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation (25 μM) than on alphaxalone potentiation (36 μM).

Figure 6.

Responses of Xenopus oocytes expressing recombinant rat α1β2γ2 subunits to GABA co-applied with potentiating steroids and 17PA. a. Effect of 17PA on 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation. b. Effect of 17PA on alphaxalone potentiation. Horizontal bars indicate the duration of drug exposure. Oocytes were clamped at -70 mV and drug concentrations were GABA (2 μM), 3α,5α-THDOC (0.5 μM), alphaxalone (0.5 μM) and 17PA (10 μM). Responses in the two panels were obtained from two separate oocytes. c. Inhibition curve for 17PA against 3α,5α-THDOC in oocytes expressing recombinant receptors. 3α,5α-THDOC concentration was constant at 0.5 μM. Potentiation refers to the fractional increase over the baseline GABA response (1.0 denotes a doubling of the response). Error bars denote standard error of the mean. The solid line is a fit predicting an IC50 of 25 μM. d. Similar inhibition curve for alphaxalone (0.5 μM) predicts an IC50 of 36 μM. e. Effects of 17PA on alphaxalone concentration response parameters. The graphs are taken from fitting a concentration response function to 8 oocytes challenged with 0.3 – 10 μM alphaxalone in the absence and presence of 10 μM 17PA. The only significant change was a shift to the right in the alphaxalone EC50, consistent with a competitive or pseudocompetitive mechanism of 17PA.

4. Discussion

17PA clearly produced a rightward shift in the dose-effect curve for 3α,5α-THP-induced sedation and significantly reduced total sleep time. This would indicate that 17PA does antagonize the GABA-modulatory effects of 3α,5α-THP in vivo in the mature mammalian brain. However, 17PA did not significantly alter the sedation dose-effect curve for the synthetic neurosteroid and anesthetic, alphaxalone, nor did 17PA significantly reduce alphaxalone total sleep time. This may suggest that 17PA is highly selective in vivo for 3α,5α-THP. This result is surprising since both 3α,5α-THP and alphaxalone are 5α-reduced steroids.

Differences in 17PA antagonist potency were also observed in the chloride flux assay, which also utilizes mature native GABAA receptors of varying subtype by looking at muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake in cerebral cortical synaptoneurosomes. Analogous to the observed in vivo sedation effects, 100 μM 17PA completely blocked 3α,5α-THP potentiation of 36Cl- uptake, whilst only partially attenuating alphaxalone and 3α,5α-THDOC potentiation. This further supports the notion that in the mature mammalian brain 17PA may be a more selective antagonist for the GABA-modulatory actions of 3α,5α-THP than for the synthetic neurosteroid, alphaxalone.

In recombinant α1β2γ2 receptors expressed in frog oocytes, 17PA has similar antagonistic actions against 3α,5α-THDOC and alphaxalone, suggesting that 3α,5α-THDOC and alphaxalone bind similar sites on this receptor subtype and 17PA partially inhibits neuroactive steroid binding to the site or allosterically reduces potentiation. Consistent with past studies of recombinant GABAA receptor preparations (Mennerick et al., 2004), 17PA exerted no direct effect upon basal 36Cl- uptake or muscimol-stimulated 36Cl- uptake, thus further confirming that 17PA acts a neurosteroid antagonist without any direct action on GABA recognition sites of GABAA receptors. Interestingly, the IC50 values for 17PA antagonism of 3α,5α-THDOC and alphaxalone are approximately 10-fold higher than the IC50 values for 17PA against 3α,5α-THP under the same experimental conditions (Mennerick et al., 2004). This difference parallels the higher effectiveness of 17PA on 3α,5α-THP vs. alphaxalone induced hypnosis (Figs. 1 and 2) and steroid potentiation of chloride flux (Fig. 5). We also tested a fixed concentration (10 μM) of 17PA against varied concentrations of alphaxalone to determine whether electrophysiology reveals changes in potency or efficacy of the potentiator. 17PA significantly increased the EC50 of alphaxalone potentiation (Figure 6e) without significant changes to other fit parameters, consistent with the general conclusion that 17PA may compete with potentiator for multiple site(s) on the GABAA α1β2γ2 receptor. This evidence that 17PA may interact with multiple sites on recombinant α1β2γ2 receptors was also suggested by single channel kinetic experiments in these cells (Akk et al., 2004).

The discrepancy between the specificity of effects of 17PA for 3α,5α-THDOC vs. alphaxalone in the loss of righting reflex assay and the Cl- flux assay compared to the recombinant receptor prep may be attributed to the fact that mature mammalian brain contains a wide variety of GABAA receptor subtypes with varying subunit composition and stochiometries (Sieghart and Sperk, 2002) that may contribute to divergent steroid binding sites. It is plausible that in vivo, alphaxalone may bind allosterically to a site on GABAA receptors that is distinct from 3α,5α-THP and this may be due to differences in receptor subtype expression intrinsic to native receptor preparations. Alternatively, 3α,5α-THP or 3α,5α-THDOC may be metabolized in vivo and ex vivo to contribute to the apparent effects of 17PA. However, this possibility seems unlikely since 17PA shows the same specificity in the recombinant receptors in vitro, where this possibility is absent.

The effect of 17PA on the chloride flux concentration response curves for both 3α,5α-THDOC and 3α,5α-THP showed a clear conversion from biphasic saturation over more than two orders of magnitude to monophasic saturation in exactly two orders of magnitude. This may suggest that 17PA has no effect on at least one neurosteroid recognition site. This may help to explain the lack of antagonist effect for alphaxalone observed in vivo. Indeed, this data might indicate that the hypnotic effects of alphaxalone are mediated by GABAA receptor subtype(s) containing a neurosteroid site that is insensitive to 17PA. Furthermore, the α1β2γ2 receptor does not appear to be involved in the hypnotic effects of alphaxalone, since 17PA partially blocked effect of alphaxalone on this receptor, but did not block hypnosis induced by alphaxalone.

The partial inhibition of neurosteroid effects by 17PA in both the recombinant and native GABAA receptor preparations is consistent with the idea that multiple neurosteroid sites may exist on individual GABAA receptor subtypes (Hosie et al., 2006). Recombinant GABAA receptors composed of β subunits alone exhibit biphasic potentiation by 3α,5α-reduced neurosteroids (Puia et al., 1990). This phenomena may involve steroid binding of the A ring vs. the C21 position at different sites on GABAA receptors (Purdy et al., 1990) and explain the monophasic properties of THDOC-21 mesylate (which replaces the C21 hydroxyl group) on GABAA receptors (Morrow et al., 1990). The ability of 17PA to partially inhibit both 3α,5α-THDOC and alphaxalone potentiation of α1β2γ2 receptors may reflect specificity for one such steroid binding site. However, further studies will be necessary to delineate neurosteroid binding sites on various subtypes of GABAA receptors.

In conclusion, studies of 17PA action on native and recombinant GABAA receptors provide further evidence for the specificity of 17PA and the heterogeneity of neurosteroid recognition sites on GABAA receptors.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NIH grants AA10564 (ALM), AA12952 (SM), and GM47969 (DFC). We thank Ann Benz and Amanda Taylor for help with oocyte experiments.

Abbreviations

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- 3α,5α-THP

3α-hydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one

- 3α,5β-THP

3α-hydroxy-5β-pregnan-20-one

- 3α,5α-THDOC

3α,21-dihydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one

- 17PA

(3α5α)-17-phenylandrost-16-en-3-ol

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Stephen P. Kelley, Departments of Psychiatry, Pharmacology and Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC.

Jamie K. Alan, Departments of Psychiatry, Pharmacology and Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC

Todd K. O’Buckley, Departments of Psychiatry, Pharmacology and Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC

Steven Mennerick, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA.

Kathiresan Krishnan, Department of Molecular Biology and Pharmacology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA.

Douglas F. Covey, Department of Molecular Biology and Pharmacology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA

A. Leslie Morrow, Departments of Psychiatry, Pharmacology and Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC.

References

- Akk G, Bracamontes JR, Covey DF, Evers A, Dao T, Steinbach JH. Neuroactive steroids have multiple actions to potentiate GABAA receptors. J Physiol. 2004;558:59–74. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.066571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Gee KW. 5α-Pregnan-3α,20α-diol behaves like a partial agonist in the modulation of GABA-stimulated chloride ion uptake by synaptoneurosomes. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1989;167:173–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90760-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovolin P, Santi M-R, Memo M, Costa E, Grayson DR. Distinct developmental patterns of rat α1, α5, γ2S and γ2L γ-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit mRNAs in vivo and in vitro. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1992;59:62–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callachan H, Cottrell GA, Hather NY, Lambert JJ, Nooney JM, Peters JA. Modulation of the GABAA receptor by progesterone metabolites. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 1987;231:359–369. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1987.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW. Comparison of the discriminative stimulus function of ethanol following intracranial and systemic administration: evidence of a central mechanism. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 1994;47:743–747. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosie AM, Wilkins ME, da Silva HM, Smart TG. Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABA(A)receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites. Nature. 2006;444:486–489. doi: 10.1038/nature05324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralic JE, Korpi ER, O’Buckley TK, Homanics GE, Morrow AL. Molecular and pharmacological characterization of GABAA receptor α1 subunit knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:1037–1045. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Khisti RT, Morrow AL. Regulation of native GABAA receptors by PKC and protein phosphatase activity. Psychopharmacology. 2005;183:241–247. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JJ, Belelli D, Hill-Venning C, Peters JA. Neurosteroids and GABAA receptor function. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1995;16:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska MD, Harrison NL, Schwartz RD, Barker JL, Paul SM. Steroid hormone metabolites are barbiturate-like modulators of the GABA receptor. Science. 1986;232:1004–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.2422758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennerick S, He Y, Jiang X, Manion BD, Wang M, Shute A, Benz A, Evers AS, Covey DF, Zorumski CF. Selective antagonism of 5alpha-reduced neurosteroid effects at GABA(A) receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1191–1197. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow AL, Pace JR, Purdy RH, Paul SM. Characterization of steroid interactions with γ-aminobutyric acid receptor-gated chloride ion channels: evidence for multiple steroid recognition sites. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;37:263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow AL, Suzdak PD, Paul SM. Steroid hormone metabolites potentiate GABA receptor-mediated chloride ion flux with nanomolar potency. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;142:483–485. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul SM, Purdy RH. Neuroactive steroids. FASEB Journal. 1992;6:2311–2322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puia G, Santi M, Vicini S, Pritchett DB, Purdy RH, Paul SM, Seeburg PH, Costa E. Neurosteroids act on recombinant human GABAA receptors. Neuron. 1990;4:759–765. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90202-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdy RH, Morrow AL, Blinn JR, Paul SM. Synthesis, metabolism, and pharmacological activity of 3α-hydroxy steroids which potentiate GABA-receptor-mediated chloride ion uptake in rat cerebral cortical synaptoneurosomes. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1990;33:1572–1581. doi: 10.1021/jm00168a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W, Sperk G. Subunit composition, distribution and function of GABA(A) receptor subtypes. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:795–816. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waud DR. On biological assays involving quantal responses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1972;183:577–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmer L, Hu Y, Kalkbrenner M, Evers A, Zorumski C, Covey D. Enantioselectivity of steroid-induced γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor modulation and anesthesia. Molecular Pharmacology. 1996;50:1581–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]