Abstract

Sustained elevation of intracellular calcium by Ca2+ release–activated Ca2+ channels is required for lymphocyte activation. Sustained Ca2+ entry requires endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ depletion and prolonged activation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R)/Ca2+ release channels. However, a major isoform in lymphocyte ER, IP3R1, is inhibited by elevated levels of cytosolic Ca2+, and the mechanism that enables the prolonged activation of IP3R1 required for lymphocyte activation is unclear. We show that IP3R1 binds to the scaffolding protein linker of activated T cells and colocalizes with the T cell receptor during activation, resulting in persistent phosphorylation of IP3R1 at Tyr353. This phosphorylation increases the sensitivity of the channel to activation by IP3 and renders the channel less sensitive to Ca2+-induced inactivation. Expression of a mutant IP3R1-Y353F channel in lymphocytes causes defective Ca2+ signaling and decreased nuclear factor of activated T cells activation. Thus, tyrosine phosphorylation of IP3R1-Y353 may have an important function in maintaining elevated cytosolic Ca2+ levels during lymphocyte activation.

Introduction

T cell activation is initiated by the engagement of the antigen/major histocompatibility complex with the T cell receptor (TCR), triggering the formation of the immunological synapse (Yokosuka et al., 2005). The immunological synapse is a dynamic, highly ordered structure that includes adaptor proteins and kinases, including the nonreceptor Src tyrosine kinases Lck and Fyn (Monks et al., 1998; Bromley et al., 2001). Once activated, these kinases trigger a phosphorylation cascade that leads to the activation of PLCγ-1, which hydrolyzes phosphotidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate into diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3; Koretzky and Myung, 2001). IP3 triggers Ca2+ release from the ER by activating the IP3 receptor (IP3R; Berridge and Irvine, 1984). ER Ca2+ depletion is sensed by stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), an EF hand containing ER transmembrane protein (Liou et al., 2005; Roos et al., 2005). ER Ca2+ depletion triggers the redistribution of STIM1 such that STIM1 forms more discrete puncta at junctional ER sites near the plasma membrane (Zhang et al., 2005; Luik et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006). STIM1 communicates the loss of ER Ca2+ to the plasma membrane Ca2+ release–activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels (Feske et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006), which colocalize with STIM1 (Luik et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006). Activation of CRAC channels triggers sustained Ca2+ influx, which is referred to as capacitative Ca2+ entry (Putney et al., 2001). Additionally, plasma membrane–localized IP3Rs potentially contribute to Ca2+ influx upon T lymphocyte activation (Dellis et al., 2006). Sustained elevation of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) causes nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) nuclear translocation, eventually leading to interleukin-2 (IL-2) production (Shibasaki et al., 1996; Lewis, 2001).

During T cell activation, [Ca2+]i elevation persists for hours after the initial activation event (Huppa et al., 2003), and sustained [Ca2+]i elevation requires prolonged IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release to keep the ER Ca2+ depleted, ensuring sustained Ca2+ influx. However, upon lymphocyte activation, global [IP3] is only transiently increased and rapidly decreases within 10 min after stimulation (Guse et al., 1993; Sei et al., 1995). Moreover, IP3R1 channel activity is inhibited by increasing [Ca2+]i (>300 nM Ca2+; Bezprozvanny et al., 1991) and the channel would be closed when exposed to the cytosolic [Ca2+] achieved during lymphocyte activation (Lewis, 2001). Thus, there must be a mechanism that enables IP3R channels to remain open when exposed to cellular conditions of globally decreasing [IP3] and elevated [Ca2+]i.

In neurons, which require elevated [IP3] (10–15 μM) to trigger IP3R activation and rapid ER Ca2+ release (Khodakhah and Ogden, 1993; Svoboda and Mainen, 1999), PLC-coupled receptors cocluster with IP3Rs, forming “signaling microdomains” to ensure efficient IP3R activation by creating locally elevated [IP3] (Delmas et al., 2002; Delmas and Brown, 2002). Similarly, in activated T cells, IP3R1 cocaps with the TCR at sites of T cell activation (Khan et al., 1992), where the cellular IP3-generating machinery, specifically linker of activated T cells (LAT) and PLCγ-1, also accumulate (Douglass and Vale, 2005; Espagnolle et al., 2007).

We had previously demonstrated that upon T cell activation, IP3R1 is phosphorylated by the Src family kinase Fyn. Additionally, in planar lipid bilayer studies, we observed that tyrosine-phosphorylated IP3R1 exhibits a higher open probability at ∼700 nM [Ca2+] than nonphosphorylated IP3R1 (Jayaraman et al., 1996). Thus, IP3R tyrosine phosphorylation could provide a mechanism that would allow sustained channel activation even as cytosolic [Ca2+] is in the range of 500–1,000 nM (Lewis, 2001), thereby maintaining a depleted ER Ca2+ store.

We identified IP3R1-Y353, located in the IP3-binding domain, as a key tyrosine phosphorylation site on IP3R1 that is phosphorylated during lymphocyte activation (Cui et al., 2004). We generated IP3R-deficient lymphocyte cell lines expressing a recombinant IP3R1 mutant (IP3R1-Y353F) that cannot be tyrosine phosphorylated at this key regulatory site. This allowed us to assess the effect of IP3R1 tyrosine phosphorylation on Ca2+ dynamics upon lymphocyte activation.

We show that in activated Jurkat T cells, Y353-phosphorylated (phosphoY353) IP3R1 clusters and colocalizes with the TCR. In cell spreading assays, the clustered Y353-phosphorylated IP3R1 forms a distinct ER substructure, facilitating the formation of a TCR-Y35–phosphorylated IP3R1 signaling microdomain. Y353-phosphorylated IP3R1 staining was clearly detectable for at least 1 h after T cell activation, suggesting that tyrosine phosphorylation of the channel is prolonged. In single channel studies, Y353-phosphorylated IP3R1 increased IP3R1 channel activity at physiological [IP3] and decreased Ca2+-dependent channel inactivation. IP3R-deficient B cells stably expressing IP3R1-Y353F exhibited decreased ER Ca2+ release, oscillations, and influx in response to B cell receptor (BCR) activation. Additionally, Jurkat T cells expressing IP3R1-Y353F exhibited a blunted NFAT response upon T cell activation, suggesting that phosphorylation of IP3R1 at Y353 is important for robust T cell activation.

Results

IP3R1 phosphoY353 colocalizes with the TCR upon T cell activation

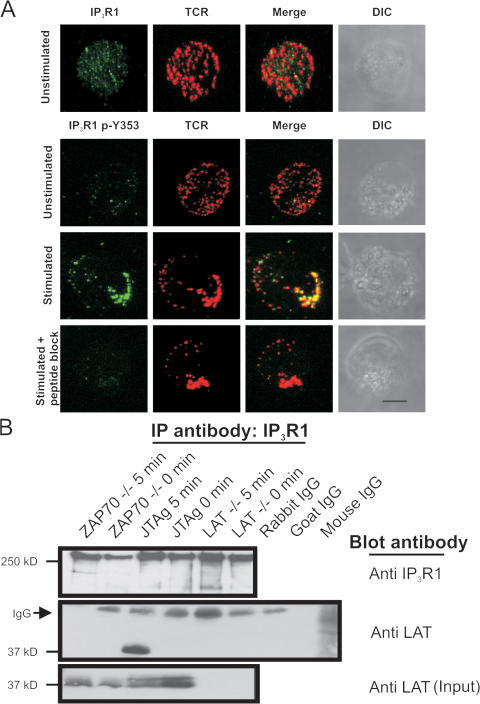

Previous studies showed that the TCR cocaps with IP3R1 upon T cell activation (Khan et al., 1992). We wanted to examine if phosphorylation at Y353 altered the ability of IP3R1 to cocap with the TCR upon T cell activation. Using an IP3R1-Y353 phosphoepitope-specific antibody, we observed uniformly distributed weak basal Y353 phosphorylation in unstimulated cells with the distribution resembling that of IP3R1 on the ER. In unstimulated T cells, the TCR/CD3 fluorescence was uniformly distributed on the plasma membrane (Fig. 1 A, top). However, upon T cell activation, both TCR/CD3 and IP3R1 phosphoY353 showed a dramatic colocalization to one site in the cell, forming a tight cluster at the site of stimulation (Fig. 1 A). Additionally, the intensity of the immunofluorescence signal for IP3R1 phosphoY353 increased significantly upon T cell activation. Preincubation of the phosphoY353 antibody with a blocking peptide decreased the phosphoY353 signal in activated T cells, confirming that the phosphoepitope antibody was specific for IP3R1 phosphoY353 (Fig. 1 A, bottom).

Figure 1.

Colocalization of IP3R1 phosphoY353 with TCR upon stimulation. (A) Jurkat T cells were incubated with mouse mAb against CD3 (OKT3) and a TRITC-conjugated goat anti–mouse antibody. Cells were fixed and stained with either an antibody against IP3R1 or a phosphoepitope-specific antibody against IP3R1 phosphoY353. Cells were examined using confocal microscopy and projection images are shown. Unstimulated T cells were examined for IP3R1 and TCR/CD3 localization. (top) IP3R1 localization is shown in green and TCR/CD3 localization is shown in red. The far right shows differential interference contrast images. Unstimulated T cells were examined for IP3R1 phosphoY353 and TCR/CD3 localization. (second from the top) IP3R1 phosphoY353 localization is shown in green and TCR/CD3 localization is shown in red. (third from the top) The localization of IP3R1 phosphoY353 and TCR/CD3 in T cells stimulated for 5 min. (bottom) Peptide block–mediated quenching of the IP3R1 phosphoY353 signal in T cells stimulated for 5 min. Approximately 30% of cells responded by displaying a reorganized, well-formed cap structure. Of that population, a majority of cells showed a robust increase in Y353 phosphorylation signal and colocalization of Y353 with the TCR. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of IP3R1 with LAT in activated Jurkat T cells. Lysate from 2 × 108 cells was incubated with anti-IP3R1 antibody to immunoprecipitate IP3R1 and blotted with anti-IP3R1 (top). (middle) Coimmunoprecipitation of LAT with IP3R1 with association occurring only in activated Jurkat T cells and not in LAT-deficient cells (LAT−/−) used as negative control or ZAP70 null cells (ZAP70−/−), suggesting a phosphorylation-mediated association between LAT and IP3R1. The arrow designates the IgG signal from the immunoprecipitating antibody. (bottom) The endogenous LAT levels in the various T cell lines used.

Additionally, we wanted to determine if the cocapping event observed upon T cell activation triggered association of IP3R1 with upstream regulators of the IP3-generating enzyme PLCγ-1. Coimmunoprecipitation assays identified LAT as a protein that associated with IP3R1 upon T cell activation (Fig. 1 B). LAT is tyrosine phosphorylated by ZAP-70 in activated T cells and the phosphorylation of LAT is essential for ensuring the robust activation of PLCγ-1 (Sommers et al., 2002). In ZAP-70–deficient T cells, LAT did not coimmunoprecipitate with IP3R1 (Fig. 1 B), which suggests that the association of IP3R1 with LAT is mediated by phosphorylation of LAT by ZAP-70.

The activation-dependent cocapping of IP3R1 phosphoY353 with the TCR and the association of IP3R1 with LAT, an essential component of the IP3-generating machinery, suggest that a signaling microdomain forms upon T cell activation whereby IP3R1 is found in close proximity to the IP3-generating machinery.

IP3R1 phosphoY353 forms a spatially restricted ER substructure colocalized with the TCR

Because IP3R1 is primarily expressed on the ER, we wanted to determine whether IP3R1 phosphoY353 clustering represented a general ER reorganization or a specific reorganization of IP3R1 phosphoY353. We performed CD3-stimulated cell spreading assays by staining stimulated Jurkat T cells with the luminal ER membrane protein calnexin. Upon T cell activation, calnexin staining remained uniformly distributed throughout the cell, indicating that in Jurkat T cells, the ER does not generally reorganize upon ER Ca2+ release (Fig. 2 A), which is consistent with previously published findings (Luik et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006). In contrast, the TCR staining showed a strong central focal point with less intense punctate staining extending out to the periphery of the cell (Fig. 2 A). Global phosphotyrosine staining colocalized with the TCR staining is also shown (Fig. 2 A, top). The bottom of Fig. 2 A shows a 3D reconstruction image of the surface immunofluorescence detected in the examined cell slice. Consistent with the 2D images, the calnexin ER staining appears to be uniformly distributed, in contrast to the centrally localized TCR signal, which suggests that no gross changes to the ER occur upon activation. In stimulated cells, IP3R1 phosphoY353 colocalized with both the TCR and phosphotyrosine staining (Fig. 2 B). 3D reconstruction of the surface fluorescence showed that IP3R1 phosphoY353 largely colocalized with the TCR signal, in sharp contrast to the calnexin staining (Fig. 2 B, bottom).

Figure 2.

IP3R1 phosphoY353 forms a spatially restricted signaling microdomain with TCR. (A, top) Calnexin staining of ER in stimulated T cells in cell spreading assay. Jurkat T cells were incubated on CD3-coated coverslips for 5 min and stained for calnexin (green), TCR/CD3 (red), and total phosphotyrosine (blue). (bottom) 3D rendering of image slice shown on top. The 3D rendering reveals global distribution of ER upon T cell activation. In the cell spreading assay, ∼70% of cells appeared to be stimulated (formed a central TCR cluster). Of that population, almost all the cells showed colocalization of Y353 with the TCR. (B, top) Staining of IP3R1 phosphoY353 in stimulated T cells. Jurkat T cells were incubated on CD3-coated coverslips for 5 min and stained for IP3R1 phosphoY353 (green), TCR/CD3 (red), and total phosphotyrosine (blue). (bottom) 3D rendering of image slice shown on top. The 3D rendering reveals localization of IP3R1 phosphoY353 to a discrete site colocalizing with TCR and phosphotyrosine with localization potentially mediated by the extrusion of the ER membrane. Bars, 5 μm.

Collectively, these data suggest that upon T cell stimulation, IP3R1 phosphoY353 undergoes a lateral redistribution along the ER membrane, accumulating in spatially restricted domains where it colocalizes with the TCR.

Persistent IP3R1 Y353 phosphorylation is detectable after T cell activation

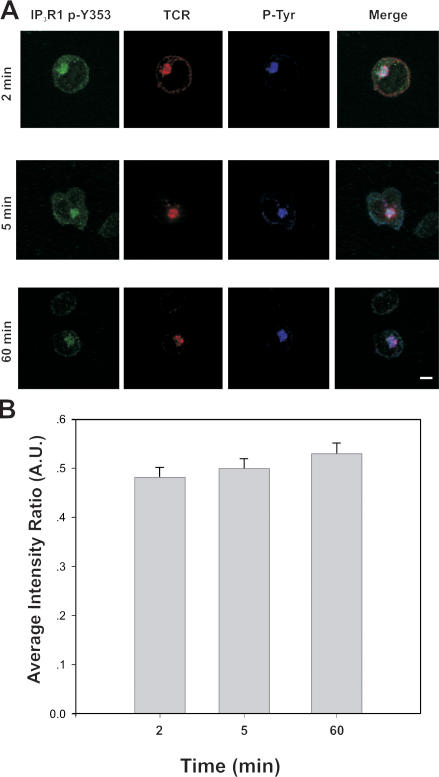

We had previously determined that Y353 was robustly tyrosine-phosphorylated by 3 min after T cell stimulation (Cui et al., 2004). To further explore the dynamics of Y353 tyrosine phosphorylation upon T cell activation, we stimulated Jurkat T cells by incubating the cells on anti-CD3 antibody–coated coverslips. IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation was strongest between 2 and 5 min after T cell activation, in agreement with our previously published data (Cui et al., 2004). Y353 phosphorylation was still detectable at 60 min after the initial T cell activation event (Fig. 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

Persistent IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation detectable after T cell activation. (A) Examining the duration of IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation upon T cell activation in a cell spreading assay. Immunofluorescence staining of phosphorylated IP3R1-Y353 was examined at 2, 5, and 60 min. IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation was detectable even 60 min after the initial activation event. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Quantification of clustering of phosphorylated IP3R1-Y353 in relation to overall TCR clustering in activated T cells. The percentage of activated T cells also displaying clustering of IP3R1 phosphoY353 was determined at various time points including 2, 5, and 60 min. Fluorescence was still observed 60 min after the initial T cell activation event. Approximately 50 cells were examined for each group from three separate experiments. Error bars represent the SEM.

IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation increases receptor sensitivity to IP3

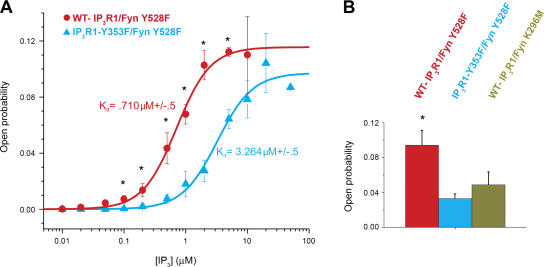

To determine if the increased affinity of tyrosine-phosphorylated IP3R1 for IP3 (Cui et al., 2004) alters IP3-mediated IP3R1 channel open probability, we conducted single-channel measurements using microsomes generated from human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells transiently cotransfected with either wild-type (WT) IP3R1 and constitutively active Fyn (Fyn Y528F) representing WT-IP3R1 phosphorylated at Y353, WT-IP3R1 and a kinase-dead mutant Fyn (Fyn K296M) representing unphosphorylated WT-IP3R1, or IP3R1-Y353F and Fyn Y528F representing WT-IP3R1, which cannot be phosphorylated at Y353. At [IP3] ranging from 100 nM to 5 μM, tyrosine-phosphorylated IP3R1 exhibited higher open probabilities compared with the mutant IP3R1-Y353F, with an ∼4.5-fold decrease in K d (WT-IP3R1, 0.710 μM ± 0.05, vs. IP3R1-Y353F, 3.264 μM ± 0.05; Fig. 4 A), which is consistent with the increased IP3 sensitivity of Y353-phosphorylated WT-IP3R1. WT-IP3R1 coexpressed with a kinase-dead Fyn mutant exhibited channel activity comparable to IP3R1-Y353F channels (Fig. 4 B). Specifically, the channel activity of phosphorylated WT-IP3R1 was higher than that of IP3R1-Y353F or unphosphorylated IP3R1 at 2 μM IP3 and 173 nM Ca2+ (Fig. 4 B). Indeed, phosphorylated WT-IP3R1 exhibited an approximately threefold increase in channel open probability in comparison to both IP3R1-Y353F and unphosphorylated IP3R1 (Fig. 4 B), suggesting that Fyn phosphorylation of IP3R1 at Y353 increases channel activity and that Y353 is a key regulatory Fyn phosphorylation site on IP3R1.

Figure 4.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of IP3R1 increases the receptor's IP3 sensitivity. (A) IP3 sensitivity of the channel in the planar lipid bilayer. Channel activity of Fyn-phosphorylated IP3R1 (WT-IP3R1/Fyn Y528F) and phosphorylated IP3R1-Y353F (IP3R1-Y353F/Fyn Y528F) was measured at 173 nM of free cytosolic Ca2+ in the presence of 2 μM ruthenium red, 1 mM Na-ATP, and various IP3 concentrations (10 nM to 10 μM). Open probability values at each IP3 concentration were calculated as a mean from several independent experiments (n = 4 for WT-IP3R1/Fyn Y528F; n = 7 for IP3R1-Y353F/Fyn Y528F; *, P < 0.05 WT vs. Y353F by t test) and fitted by the equation described by Tang et al. (2003). (B) Comparison of open probability for Fyn-phosphorylated WT-IP3R1, Fyn-phosphorylated IP3R1-Y353F, and WT-IP3R1 coexpressed with kinase-dead Fyn (unphosphorylated WT-IP3R1). At 173 nM Ca2+ and 2 μM IP3, Fyn-phosphorylated WT-IP3R1 exhibits an approximately threefold increase in channel open probability as compared with both IP3R1-Y353F and unphosphorylated WT-IP3R1 (*, P < 0.05 phosphorylated WT vs. Y353F and phosphorylated vs. unphosphorylated WT by t test). Error bars represent the SEM.

Collectively, these data suggest that IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation helps maintain IP3R1 in the open state, even as [IP3] levels decline after activation.

IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation reduces Ca2+-dependent IP3R1 channel inactivation

Having demonstrated that tyrosine phosphorylation of IP3R1 results in increased channel open probability over a range of [IP3], we now wanted to determine whether tyrosine phosphorylation modulates the sensitivity of IP3R1 to Ca2+-dependent channel inactivation. IP3R1 channel activity exhibits a bell-shaped dependence on cytosolic [Ca2+], being activated at low [Ca2+] (∼200–300 nM) and inactivated at higher [Ca2+] (Bezprozvanny et al., 1991; Yoneshima et al., 1997; Kaznacheyeva et al., 1998; Picard et al., 1998). In addition to being activated by IP3, IP3R1 has to remain open at elevated cytosolic [Ca2+] to allow Ca2+-dependent lymphocyte activation to proceed.

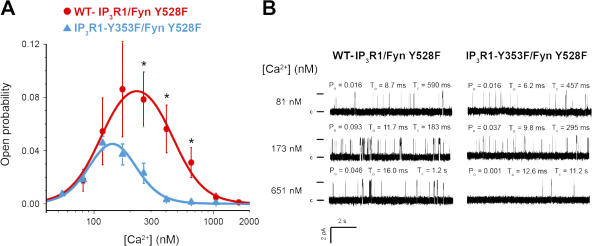

To determine whether phosphorylation of IP3R1-Y353 can modulate the Ca2+-dependent regulation of the channel, we examined the single channel properties of the channel in response to a physiological range of [Ca2+] in the presence of 2 μM IP3. At [Ca2+] that has been shown to inhibit unphosphorylated WT-IP3R1 (>200–300 nM; Bezprozvanny et al., 1991), tyrosine-phosphorylated WT-IP3R1 exhibited a significantly higher open probability (threefold increase, P < 0.05, n > 3 for each channel type) than IP3R1-Y353F (Fig. 5 A). Mean open times and current amplitudes were similar for both WT-IP3R1 and IP3R1-Y353F (Fig. 5 B). To determine whether the increased open probability of the tyrosine-phosphorylated WT-IP3R1 was influenced by its increased sensitivity to [IP3] compared with IP3R1-Y353F, we also compared the activity of these channels at 10 and 100 μM [IP3]. At both 10 and 100 μM IP3, the difference in channel activity between tyrosine-phosphorylated WT-IP3R1 and IP3R1-Y353F was not significant (unpublished data). Thus, tyrosine phosphorylation of Y353 on IP3R1 increases channel open probability and reduces Ca2+-dependent channel inactivation at [Ca2+] of ∼200–1,000 nM, which is comparable to the level of sustained [Ca2+]i observed upon lymphocyte activation.

Figure 5.

Ca2+ dependence of WT-IP3R1 and IP3R1-Y353F single-channel activity. (A) A comparison of the open probability of Fyn-phosphorylated WT-IP3R1 and phosphorylated IP3R1-Y353F at varying Ca2+ concentrations. The activity of the channel was measured in the presence of 2 μm IP3, 2 μM ruthenium red, and 1 mM Na-ATP at different Ca2+ concentrations ranging from 50 nM to 2.5 μM. Each data point represents the open probability calculated as a mean from several independent experiments shown as mean ± SEM. Ca2+ dependences of tyrosine-phosphorylated IP3R1 (WT-IP3R1/Fyn Y528F, n = 3) and IP3R1-Y353F (IP3R1-Y353F/Fyn Y528F, n = 7) were fitted by the bell-shaped equation (*, P < 0.05 WT vs. Y353F by t test). (B) Representative traces of IP3R1 activity at three different Ca2+ concentrations and the corresponding open probability (Po), mean open time (to), and closed time (tc) of the channels. Single channel openings are plotted as upward deflections; the open and closed (c) states of the channel are indicated by horizontal bars at the beginning of the traces.

IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation enhances Ca2+ entry in B lymphocytes

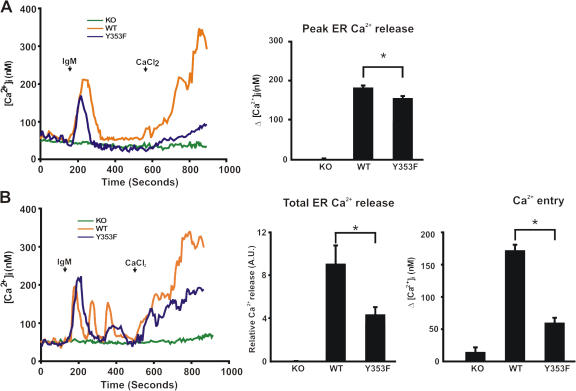

We previously showed that IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation slows the decay of the Ca2+ release transient upon B cell activation (Cui et al., 2004). To further examine both BCR-induced ER Ca2+ release and influx, single-cell studies were conducted using IP3R null DT40 B cell lines (IP3R-KO; Sugawara et al., 1997) stably transfected with either WT-IP3R1 or IP3R1-Y353F. Expression levels of WT-IP3R1 and IP3R1-Y353F in the stably transfected DT40 cell lines were comparable (unpublished data). IP3R-KO cells exhibited no BCR-induced ER Ca2+ release and the addition of extracellular Ca2+ did not trigger Ca2+ influx (Fig. 6, A and B). Both WT-IP3R1 and IP3R1-Y353F cells responded to BCR stimulation manifested as IP3-induced ER Ca2+ release (Fig. 6, A and B). Upon BCR stimulation, both the amplitude of the first peak of Ca2+ release and the total Ca2+ release were increased in DT40 cells expressing WT-IP3R1 as compared with IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells (Fig. 6, A and B). Discrete Ca2+ oscillations, representing cyclical Ca2+ release from and reuptake into ER stores, were observed in ∼30% of WT-IP3R1–expressing cells, compared with <10% of IP3R1-Y353F cells (Fig. 6 B), whereas only a single peak of ER Ca2+ release was observed in the remaining cells studied. This suggests that the phosphorylation of IP3R1 at Y353 can increase the likelihood that the cell will oscillate upon lymphocyte activation. ER Ca2+ loading was similar and the pharmacological emptying of the ER using the SR/ER Ca2+ ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin showed that the Ca2+ entry machinery was otherwise intact in WT-IP3R1– versus IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200708200/DC1). Also, upon addition of extracellular CaCl2, Ca2+ influx was significantly reduced in IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells compared with WT-IP3R1–expressing cells in the time measured (Fig. 6 B), suggesting that in cells expressing IP3R1-Y353F, the kinetics of Ca2+ influx are slower in comparison to WT-IP3R1–expressing cells. Collectively, these data suggest that tyrosine phosphorylation of IP3R1 at Y353 triggers greater emptying of ER Ca2+ stores, thereby causing greater Ca2+ influx via capacitative Ca2+ entry.

Figure 6.

Effects of IP3R1-Y353F on Ca2+ influx after BCR stimulation. (A) Peak of ER Ca2+ release measured in single cells upon BCR stimulation. Cytosolic Ca2+ was measured in a nominally Ca2+-free medium. 5 μg/ml of anti-IgM antibody and 1 mM CaCl2 were applied at time points indicated by arrows. The histogram shows the peak of Ca2+ release in WT-IP3R1, IP3R1-Y353F, and IP3R-KO cells upon stimulation. Both oscillating and nonoscillating cells were used in the analyses and only the initial peak of Ca2+ release was measured in the stimulated cells. (B) Total ER Ca2+ release measured in single cells upon BCR stimulation. (left) Representative traces of Ca2+ oscillations observed in both WT-IP3R1– and IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells upon IgM stimulation. (middle) The total [Ca2+]i upon IgM stimulation with WT-IP3R1–expressing cells showing approximately twofold increase relative to Ca2+ release in comparison to IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells (8.9 + 1.87 vs. 4.27 + 0.83; *, P < 0.05). (right) Quantification of total BCR-induced Ca2+ entry. The total Ca2+ entry of IP3R-KO (n = 54), WT-IP3R1–expressing (n = 33), and IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells (n = 21) is shown. Data represent the mean ± SEM (*, P < 0.05 WT vs. Y353F by t test). Total ER Ca2+ release and Ca2+ entry histograms were plotted by measuring the area under the curve after stimulation. All cells that responded to stimulation by IgM were analyzed.

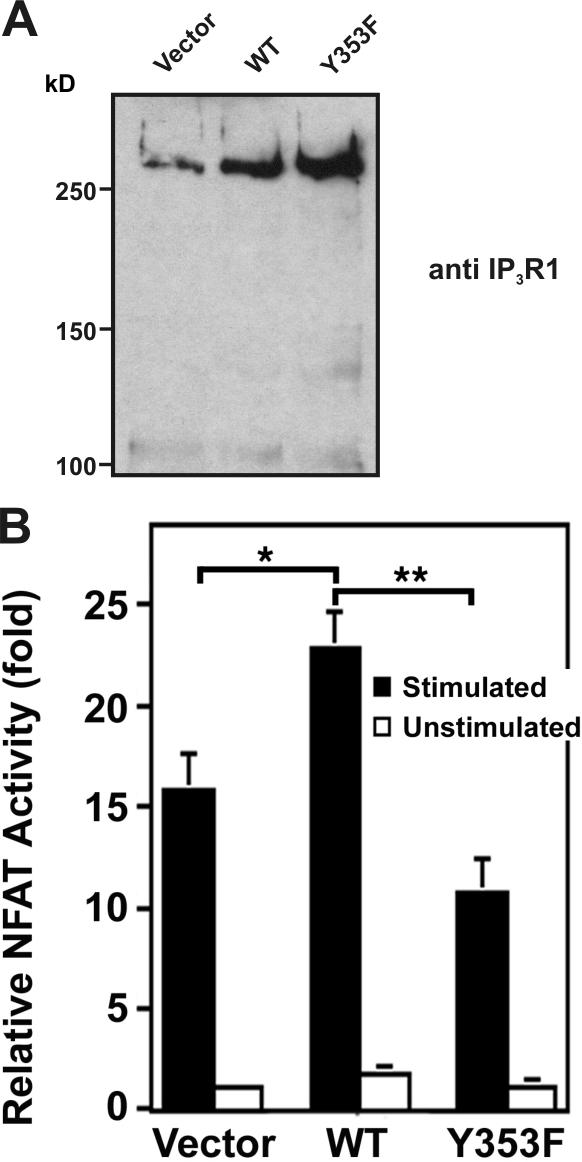

NFAT activity is enhanced by the phosphorylation of IP3R1-Y353

Elevation of [Ca2+]i triggers NFAT translocation to the nucleus, eventually leading to IL-2 production (Koretzky and Myung, 2001). Previous studies revealed that DT40 cells expressing only IP3R1 exhibited decreased Ca2+ oscillations upon IgM stimulation (Miyakawa et al., 1999) and that decreasing the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations significantly mutes the NFAT response (Dolmetsch et al., 1998). Also, in lymphocytes, which express all three IP3R isotypes, there appears to be considerable cooperativity in terms of the Ca2+ response upon lymphocyte stimulation (Miyakawa et al., 1999). Thus, to best address whether impaired Ca2+ influx observed in IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells affected downstream responses, Jurkat cells were transiently cotransfected with an NFAT–luciferase reporter construct and either an empty vector, WT-IP3R1, or IP3R1-Y353F. Immunoblotting of transfected cell lysates revealed the levels of WT-IP3R1 and IP3R1-Y353F (Fig. 7 A). In stimulated cells expressing WT-IP3R1, NFAT activity (normalized to the level of IP3R1 expression as shown in Fig. 7 A) was increased ∼1.5-fold compared to vector-transfected cells (Fig. 7 B). This increase was significantly blunted in cells expressing IP3R1-Y353F (Fig. 7 B). Collectively, these data suggest that phosphorylation of IP3R1 at Y353 ensures robust NFAT activation.

Figure 7.

Effect of IP3R1 Y353 phosphorylation on NFAT activity. (A) Immunoblotting of lysates from 106 transfected Jurkat T cells with anti-IP3R1 antibody showed comparable overexpression of WT-IP3R1 and IP3R1-Y353F. (B) Relative NFAT-dependent luciferase activity. 106 Jurkat cells were transiently transfected with WT-IP3R1, IP3R1-Y353F, or pcDNA3.1 vector together with an NFAT–firefly luciferase reporter assay construct and a TK-Renilla luciferase construct as a control for luciferase transfection efficiency. After stimulation with OKT3 (anti-CD3 antibody), cells were lysed and the lysates were assayed for NFAT-luciferase activity, quenched, and assayed for TK-luciferase activity in triplicate. NFAT activity is expressed as relative NFAT luminescence normalized to TK luminescence and adjusted for IP3R1 expression levels. The results are shown as fold stimulation over nonstimulated vector control. Data were presented as the mean ± SEM of seven independent Jurkat preparations assayed in triplicate. (*, P < 0.05 WT vs. vector by t test; **, P < 0.05 WT vs. Y353F by t test).

Discussion

In this paper, we demonstrate that IP3R1-Y353 phosphorylation is important for antigen-induced Ca2+ signaling during lymphocyte activation. [Ca2+]i must be elevated for several hours after lymphocyte activation to ensure effective activation of downstream events such as IL-2 production (Huppa et al., 2003). The elevation of [Ca2+]i is supported by ER Ca2+ store depletion, triggering sustained CRAC channel activation. Although recent work has revealed that the ER transmembrane protein STIM1 communicates ER store depletion to CRAC channels (Zhang et al., 2005), thereby triggering Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane, mechanisms used by the cell to maintain depleted ER stores remain unclear. Although IP3Rs constitute the primary ER Ca2+ release channel in lymphocytes, the role of IP3Rs in mediating sustained ER depletion has been questioned. This is primarily because bulk [IP3] decreases to basal levels shortly after T cell activation (Guse et al., 1993; Sei et al., 1995) and [Ca2+]i is elevated to levels that inhibit IP3R1 channel activity in single-channel studies (Bezprozvanny et al., 1991).

In various cell types, physiological responses to extracellular agonists elicit sustained IP3R activation. The formation of signaling complexes bringing IP3Rs in close apposition to the cellular IP3-generating machinery is believed to facilitate the activation of the channel even as global [IP3] decreases. In neurons, coclustering of bradykinin receptors with IP3Rs creates a locally elevated IP3 environment upon receptor stimulation (Delmas et al., 2002). Additionally, in kidney cells, IP3R complexes with Na/K ATPase, Src, and PLC-γ1, creating sites of locally elevated IP3 production (Yuan et al., 2005). We show that upon T cell activation, clustering of IP3R1 phosphoY353 with the TCR and association of IP3R1 with LAT can also create a locally elevated IP3 environment, ensuring activation of IP3Rs even as global IP3 levels are decreasing. Moreover, modeling studies have shown that receptor clustering decreases the activation threshold and increases the response range to ligand (Bray et al., 1998). Collectively, with the phosphorylated receptor's increased affinity for IP3 (Cui et al., 2004), the clustering of phosphorylated IP3R1 upon T cell activation suggests a novel mechanistic solution to the problem of rapidly decreasing [IP3].

Recently, it has been shown that T cell activation is mediated and sustained by TCR signaling microclusters, which form on the cell surface (Yokosuka et al., 2005). Interestingly the stimulated T cell in Fig. 1 A reveals a colocalization pattern between the TCR and IP3R1 phosphoY353, which is suggestive of signaling microclusters, specifically in the TCR–IP3R1 phosphoY353 colocalization observed near the region where the antibody-mediated TCR clustering is the strongest. This is more clearly observed in the cell spreading assay in Fig. 2 B. It appears that both CD3 and IP3R1 phosphoY353 are coclustered at the center and edges of the stimulated cell. The staining of both proteins appears more punctuate in the periphery of the cell, with the clusters at the edge of the cell resembling signaling microclusters. The distribution of phosphorylated IP3R1 into microclusters suggests the formation of discrete sites of ER–plasma membrane (PM) junctions, where maximal activation of phosphorylated IP3R1 could occur, which is reminiscent of the ER–PM junctions observed upon thapsagargin-induced ER Ca2+ release in Jurkat T cells (Luik et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006).

Additionally, because cytosolic Ca2+ levels must remain elevated for 2–10 h after T cell activation (Huppa et al., 2003), persistent phosphorylation of IP3R1-Y353 even 60 min after the initial T cell activation event provides for sustained receptor activation, ensuring both discrete and controlled ER Ca2+ release even as global [IP3] decreases.

At the single channel level, phosphorylation of IP3R1 at Y353 increases the channel's sensitivity to IP3, allowing increased IP3-dependent ER Ca2+ release at [IP3] <10 μM and reduces Ca2+-dependent inactivation of IP3R1 in the physiological range of [Ca2+] that occurs during lymphocyte activation, allowing for more efficient IP3R1 activation at decreasing [IP3]. It should be noted that the difference in Ca2+-dependent activation of tyrosine-phosphorylated channels can be explained in part by the concurrent difference in IP3 sensitivity. We found that at higher [IP3], the difference in Ca2+-dependent activation between phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated channels was reduced. Thus, given the complex relationship between Ca2+- and IP3-dependent effects on IP3R1 channel activity, it is likely that the responses observed in cells represent combined effects. We propose that phosphorylation of IP3R1 at Y353 provides a mechanism for maintaining IP3R1 channel activity in the presence of globally decreasing [IP3] and inhibitory cytosolic [Ca2+].

In single cell studies, WT-IP3R1–expressing cells exhibited increased ER Ca2+ release and increased Ca2+ oscillations from the ER upon IgM stimulation in comparison to IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells. This increased ER Ca2+ release in WT-IP3R1–expressing cells translated to increased Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane. Current work detailing the communication between depleted ER stores and CRAC channels on the plasma membrane suggests that STIM1 is essential for communicating the level of ER Ca2+ to CRAC channels. Depletion of STIM1 has been shown to trigger decreased store-operated Ca2+ entry and a loss of CRAC channel activation (Liou et al., 2005; Roos et al., 2005). Recent work has shown that upon ER Ca2+ depletion, STIM1 reorganizes into discrete puncta at specific sites on the ER and colocalizes and potentially interacts with CRAC channels on the plasma membrane (Roos et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Luik et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006; Yeromin et al., 2006). These closely apposed ER–PM junctions appear to be discrete sites of Ca2+ entry on the plasma membrane surface and imply a locally regulated elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry. These recent findings strengthen the argument for the formation of spatially restricted ER–PM junctions on T cells, where signaling microdomains can occur and local regulation of Ca2+ signaling can be observed. It would be interesting to determine the localization of phosphorylated IP3R1 relative to the STIM1-CRAC channel signaling unit upon T cell activation to determine if the phosphorylated receptor colocalizes with or modulates local Ca2+ signaling dynamics. Also, recent work has suggested that plasma membrane–localized IP3R1s influence Ca2+ influx (Dellis et al., 2006). As such, the contribution of plasma membrane–localized, Y353-phosphorylated WT-IP3R1 to the increased Ca2+ influx observed upon addition of extracellular Ca2+ is a possibility that cannot be excluded.

The downstream effect of increased ER Ca2+ release and influx is clearly demonstrated in the increased NFAT activity observed in Jurkat cells expressing WT-IP3R1, a response that is blunted in IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells.

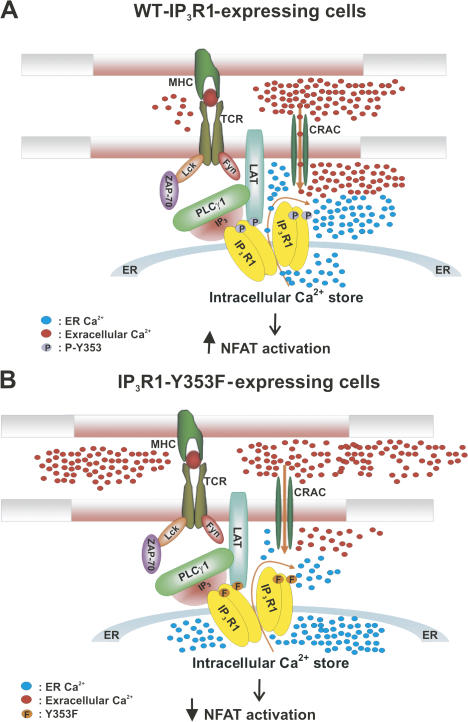

Thus, in a model of sustained receptor activation, as global [IP3] decreases and [Ca2+] reaches levels that inhibit nonphosphorylated IP3R, IP3R1 phosphoY353 is clustered on the ER in close proximity to the TCR, creating a spatially restricted signaling microdomain. Additionally, IP3R1 phosphoY353 exhibits increased sensitivity to varying [IP3] and exhibits less channel inhibition at increasing [Ca2+], thereby allowing it to remain active at inhibitory [Ca2+]. This sustained receptor activity contributes to elevating cytosolic Ca2+ levels both by ER Ca2+ release and CRAC channel activation, thereby ensuring robust lymphocyte proliferation (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Model of IP3R1-TCR signal microdomain formation upon T cell activation. (A) Activation of the TCR via interaction with an antigen-presenting cell causes recruitment and activation of Src family tyrosine kinases (Lck and Fyn). Antigen receptor engagement also induces capping of the TCR and phosphorylated IP3R1 Y353 at the site of lymphocyte activation. Src family tyrosine kinases phosphorylate and activate ZAP-70. ZAP-70 phosphorylates the adaptor protein LAT and induces recruitment and activation of PLCγ-1 to LAT. LAT also associates with IP3R1, bringing it closer to the signaling complex. IP3R1 is phosphorylated at Y353 by Fyn and activated by local [IP3], thereby triggering ER Ca2+ release, which couples to the activation of CRAC channels and induces Ca2+ influx and NFAT activation. (B) In lymphocytes expressing an IP3R1-Y353F mutant receptor, loss of the phosphorylation site on IP3R1 leads to decreased Ca2+ release from ER Ca2+ stores, which couples to decreased CRAC channel activation, causing decreased Ca2+ influx and leading to decreased NFAT activation.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Antibodies that recognize IP3R1 and IP3R1 phosphoY353 have been described previously (Cui et al., 2004). Antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 and mouse anti-LAT (Millipore); mouse anti–chicken IgM M4 (SouthernBiotech); mouse anti-CD3 OKT3 (Ortho Biotech); and anti–mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) were used.

Cell culture and transfection

Jurkat T lymphocytes, ANJ3 LAT–deficient cells (provided by L. Samelson, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), and ZAP-70 null cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 8% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 5% CO2. Chicken DT40 B cells and stable IP3R1-transfected cell lines were cultured as described previously (Cui et al., 2004). HEK293 cells were maintained in DME supplemented with 10% FBS and transfected with plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen).

Single channel recording and data acquisition

Microsomes from HEK293 cells expressing WT-IP3R1 cotransfected with Fyn Y528F, WT-IP3R1 cotransfected with Fyn K296M, or IP3R1-Y353F cotransfected with Fyn Y528F were prepared as described previously (Kaznacheyeva et al., 1998). In brief, pellets were resuspended in homogenization buffer A (1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, and 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0) supplemented with protease inhibitors and homogenized with a glass homogenizer (Teflon; DuPont). After a second homogenization step with buffer B (0.5 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Hepes, and 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5), the cell lysate was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min. Consecutive supernatants were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min and 100,000 g for 124 min (rotor AH-629; Ultra Pro 80; Sorvall). The pellet from the last centrifugation was resuspended in buffer C (10% sucrose and 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.0).

The recombinant IP3R1s were reconstituted by spontaneous fusion of microsomes into the planar lipid bilayer (mixture of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine in a 3:1 ratio; Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.). Planar lipid bilayers were formed across a 200-μm aperture in a polysulfonate cup (Warner Instruments), which separated two bathing solutions (1 mM EGTA, 1 mM HEDTA, 250/125 mM Hepes/Tris, 50 mM KCl, and 0.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.35, as a cis solution; and 53 mM Ba[OH]2, 50 mM KCl, and 250 mM Hepes, pH 7.35, as a trans solution). After incorporation, IP3R1 channels were activated with 2 μM IP3 and the activity was recorded in the presence of 2 μM ruthenium red and 1 mM Na-ATP. Concentration of free Ca2+ in the cis chamber ranged from 80 nM to 2.5 μM by consecutive addition of CaCl2 from 20-mM stock and was calculated with WinMaxC program (version 2.50; http://www.stanford.edu/∼cpatton/maxc.html; Bers et al., 1994). In IP3 dependence experiments, the activity of the channels was measured in the presence of 173 nM free Ca2+, 2 μM ruthenium red, and 1 mM Na-ATP at an IP3 concentration range of 10 nM to 50 μM. Single channel currents were recorded at 0 mV using the Axopatch 200A patch clamp amplifier (MDS Analytical Technologies) in gap-free mode, filtered at 500 Hz, and digitized at 4 kHz. Data acquisition was performed using Digidata 1322A and Axoscope 9 software (both from MDS Analytical Technologies). The recordings were stored on a computer (Pentium) and analyzed using pClamp 6.0.2 (MDS Analystical Technologies) and Origin software (6.0; OriginLab). The data in Ca2+- and IP3-dependence experiments was fitted with the curves as described previously (Tang et al., 2003). Only channels that exhibited maximum channel open probability exceeding 2% were included in the data analyses.

Cytosolic Ca2+ measurement

For single-cell calcium imaging, DT40 cells were loaded with 2 μM Fura-2/AM in culture medium at 37°C for 20 min, washed twice with culture medium, and washed once with nominally Ca2+-free medium (107 mM NaCl, 7.2 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucoses, and 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.2). Glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine were placed in a perfusion chamber (Photon Technology International) mounted on the stage of the microscope. Ca2+ images were captured as described previously (Cui et al., 2002). Only WT-IP3R1– and IP3R1-Y353F–expressing lymphocytes that showed Ca2+ release upon BCR stimulation were used for the data analysis. For the measurement of the peak of [Ca2+]i, cells that showed only a single peak of Ca2+ release and exhibited oscillations were included in the histogram analysis. For oscillating cells, only the first peak of Ca2+ release was measured. For total ER Ca2+ release measurements, all cells that showed Ca2+ release upon IgM addition were measured. The analysis included the multiple Ca2+ release events observed in oscillating WT-IP3R1– and IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells. Additionally, total [Ca2+]i release upon IgM stimulation was calculated by measuring the area (Fura2 ratio subtracted from baseline and integrated with time) for all cells showing release upon IgM stimulation.

Ca2+ entry was calculated by integrating the peak [Ca2+]i with respect to time 5 min after the introduction of 1.5 mM CaCl2. 1,500 s after addition of 1mM Ca2+, ionomycin and EGTA were added to calculate maximum and minimum Ca2+. For cells treated with thapsagargin, no significant difference in Ca2+ entry was observed for the WT-IP3R1–expressing cells when compared with IP3R1-Y353F–expressing cells upon addition of extracellular Ca2+. All measurements shown are representative of three to five independent experiments.

NFAT luciferase assay

106 Jurkat cells were cotransfected with 3 μg WT-IP3R1 or IP3R1-Y353F plasmids with a 2-μg NFAT-luciferase plasmid and a 15-ng pRL–thymidine kinase (TK) control plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 in 24-well plates. 36 h after transfection, cells were split into two groups and were either stimulated using 1 μg/ml OKT3 anti-CD3 antibody or not stimulated as a control for 7 h, respectively. A luciferase assay was performed using a dual-luciferase assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The NFAT activity was expressed as fold excess over unstimulated cells for all three populations of cells (vector alone, WT-IP3R1–transfected, and Y353F IP3R1) and was normalized for IP3R1 expression. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of seven independent experiments each performed in triplicate. Statistical significance was determined using a t test.

Cell stimulation, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting

For the LAT coimmunoprecipitation experiment, 2 × 108 cells of each cell type were stimulated by incubating with 25 μg/ml anti-CD3 mAb (OKT3) at 37°C for 2 min followed by 15 μg/ml goat anti–mouse IgG for 5 min at 37°C. 10 ml of ice-cold PBS was added to stop stimulation and cells were harvested and lysed for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting as described previously (Cui et al., 2004).

Confocal microscopy

For capping experiments imaging IP3R1, Jurkat T cells were stimulated with 20 μg/ml OKT3 for 1 h on ice followed by cross-linking with 10 μg/ml of TRITC-labeled goat anti–mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 1 h on ice. Cells were pipetted onto poly-l-lysine–coated coverslips and incubated at 37°C for 5 min. The cells were then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed, permeabilized, and stained with an antibody against IP3R1 at 1:250 dilution or IP3R1 phosphoY353 at 1:10,000 dilution followed by a secondary antibody stain of Alexa 488 goat anti–rabbit at 1:300 dilution (Invitrogen). For peptide blocking experiments, the IP3R1 phosphoY353 antibody was preincubated with peptide at 4°C for 1 h before use. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Slowfade Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen). The slides were examined with a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510 META) with a 100× 1.3 Plan-Neofluor objective lens (both from Carl Zeiss, Inc.). All experiments were conducted at room temperature. Alexa 488 and TRITC were excited at 488 and 543 nm, respectively, and emissions were collected at 500–550 and >585 nm, respectively. Software (MetaView; Carl Zeiss, Inc.) was used for both acquisition and image processing. Z stack images were collected at an optical section thickness of 1 μM with maximum intensity projections of these sections computed to yield a projection image using MetaView software.

Cell spreading assay

The assay was performed as described previously (Bunnell et al., 2003) with minor modifications. Coverslips coated with anti-CD3 stimulatory antibody (clone HIT3a; BD Biosciences) were preincubated at 37°C for 30 min before use. Jurkat T cells were added, the cells were incubated at 37°C for various time points, and the stimulation was stopped by the addition of paraformaldehyde. The samples were fixed for 30 min at 37°C and permeabilized by the addition of 500 μg/ml digitonin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min at room temperature. The samples were washed with PFN staining buffer (PBS, 10% FCS, and 0.02% azide) and blocked for 1 h with blocking buffer (2% goat serum and PFN buffer) at room temperature. The samples were then incubated with either anticalnexin at 1:1,000 (Sigma-Aldrich) or IP3R1 phosphoY353 at 1:5,000 dilution, and 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine at 2 μg/ml dilution and anti-TCR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at 2 μg/ml for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were incubated with secondary antibody stains of Alexa 488 goat anti–rabbit, Alexa 568 goat anti–mouse IgG1, and Alexa 680 goat anti–mouse IgG2b, all at 1:250 dilution (Invitrogen). The samples were washed and coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Slowfade Gold antifade reagent. The slides were examined at room temperature using a microscope (Axioimager.Z1) with a 63× 1.3 Plan-Neofluor objective lens and images were captured using a camera (Axiocam MRm; all from Carl Zeiss, Inc.). Axiovision 4.6.3 software (Carl Zeiss, Inc.) was used for both acquisition and image processing. Z stack images were collected at an optical section thickness of 0.5 μm through the entire cell using the Apotome slider on the Axioimager.Z1 with maximum intensity projections of these sections computed to yield a projection image for 3D surface rendering using Axiovision 4.6.3. Time-course analysis of Y353 phosphorylation was performed by comparing the fluorescence intensities of IP3R1 phosphoY353 versus TCR for each cell slice in the z stack with the Metamorph imaging program. The area encompassing the clustered TCR was used to compare relative fluorescence intensities for each slice for each individual cell. Approximately 50 cells were analyzed for each time point from three independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the t test for paired samples. A computer program (Origin Pharmacology DoseResp; MicroCal) was used for statistical analysis. The EC50 values were calculated using SigmaPlot 8.0 (Systat Software Inc.) from a sigmoidal curve fitting of all the data points.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that treatment of IP3R-KO, WT-IP3R1, or IP3R1-Y353F DT40 cells with thapsigargin triggers comparable ER Ca2+ mobilization. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200708200/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Konstantina Alexandropoulos for assistance with NFAT measurements. We also thank Dr. Lawrence Samelson at the National Institutes of Health for the kind gift of the ANJ3 LAT-deficient cell line.

The authors declare that they have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used in this paper: BCR, B cell receptor; [Ca2+]i, intracellular Ca2+; CRAC, Ca2+ release–activated Ca2+; HEK, human embryonic kidney; IL-2, interleukin-2; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; IP3R, IP3 receptor; LAT, linker of activated T cells; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; PM, plasma membrane; STIM1, stromal interaction molecule 1; TCR, T cell receptor; TK, thymidine kinase; WT, wild type.

References

- Berridge, M.J., and R.F. Irvine. 1984. Inositol trisphosphate, a novel second messenger in cellular signal transduction. Nature. 312:315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers, D.M., C.W. Patton, and R. Nuccitelli. 1994. A practical guide to the preparation of Ca2+ buffers. Methods Cell Biol. 40:3–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny, I., J. Watras, and B. Ehrlich. 1991. Bell-shaped calcium response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature. 351:751–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D., M.D. Levin, and C.J. Morton-Firth. 1998. Receptor clustering as a cellular mechanism to control sensitivity. Nature. 393:85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, S.K., W.R. Burack, K.G. Johnson, K. Somersalo, T.N. Sims, C. Sumen, M.M. Davis, A.S. Shaw, P.M. Allen, and M.L. Dustin. 2001. The immunological synapse. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:375–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell, S.C., V.A. Barr, C.L. Fuller, and L.E. Samelson. 2003. High-resolution multicolor imaging of dynamic signaling complexes in T cells stimulated by planar substrates. Sci. STKE. 2003:PL8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J., J.S. Bian, A. Kagan, and T.V. McDonald. 2002. CaT1 contributes to the stores-operated calcium current in Jurkat T-lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47175–47183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J., S.J. Matkovich, N. deSouza, S. Li, N. Rosemblit, and A.R. Marks. 2004. Regulation of the type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor by phosphorylation at tyrosine 353. J. Biol. Chem. 279:16311–16316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellis, O., S.G. Dedos, S.C. Tovey, R. Taufiq Ur, S.J. Dubel, and C.W. Taylor. 2006. Ca2+ entry through plasma membrane IP3 receptors. Science. 313:229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, P., and D.A. Brown. 2002. Junctional signaling microdomains: bridging the gap between the neuronal cell surface and Ca2+ stores. Neuron. 36:787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, P., N. Wanaverbecq, F.C. Abogadie, M. Mistry, and D.A. Brown. 2002. Signaling microdomains define the specificity of receptor-mediated InsP(3) pathways in neurons. Neuron. 34:209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch, R.E., K. Xu, and R.S. Lewis. 1998. Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature. 392:933–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass, A.D., and R.D. Vale. 2005. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein-protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell. 121:937–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espagnolle, N., D. Depoil, R. Zaru, C. Demeur, E. Champagne, M. Guiraud, and S. Valitutti. 2007. CD2 and TCR synergize for the activation of phospholipase Cgamma1/calcium pathway at the immunological synapse. Int. Immunol. 19:239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske, S., Y. Gwack, M. Prakriya, S. Srikanth, S.H. Puppel, B. Tanasa, P.G. Hogan, R.S. Lewis, M. Daly, and A. Rao. 2006. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 441:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guse, A.H., E. Roth, and F. Emmrich. 1993. Intracellular Ca2+ pools in Jurkat T-lymphocytes. Biochem. J. 291:447–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppa, J.B., M. Gleimer, C. Sumen, and M.M. Davis. 2003. Continuous T cell receptor signaling required for synapse maintenance and full effector potential. Nat. Immunol. 4:749–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman, T., K. Ondrias, E. Ondriasova, and A.R. Marks. 1996. Regulation of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor by tyrosine phosphorylation. Science. 272:1492–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaznacheyeva, E., V.D. Lupu, and I. Bezprozvanny. 1998. Single-channel properties of inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor heterologously expressed in HEK-293 cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 111:847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A., J.P. Steiner, M.G. Klein, M.F. Schneider, and S.H. Snyder. 1992. IP3 receptor: localization to plasma membrane of T cells and cocapping with the T cell receptor. Science. 257:815–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodakhah, K., and D. Ogden. 1993. Functional heterogeneity of calcium release by inositol trisphosphate in single Purkinje neurones, cultured cerebellar astrocytes, and peripheral tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:4976–4980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koretzky, G.A., and P.S. Myung. 2001. Positive and negative regulation of T-cell activation by adaptor proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.S. 2001. Calcium signaling mechanisms in T lymphocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:497–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou, J., M.L. Kim, W.D. Heo, J.T. Jones, J.W. Myers, J.E. Ferrell Jr., and T. Meyer. 2005. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 15:1235–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luik, R.M., M.M. Wu, J. Buchanan, and R.S. Lewis. 2006. The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER–plasma membrane junctions. J. Cell Biol. 174:815–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa, T., A. Maeda, T. Yamazawa, K. Hirose, T. Kurosaki, and M. Iino. 1999. Encoding of Ca2+ signals by differential expression of IP3 receptor subtypes. EMBO J. 18:1303–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monks, C.R., B.A. Freiberg, H. Kupfer, N. Sciaky, and A. Kupfer. 1998. Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells. Nature. 395:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard, L., J.F. Coquil, and J.P. Mauger. 1998. Multiple mechanisms of regulation of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor by calcium. Cell Calcium. 23:339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney, J.W., Jr., L.M. Broad, F.J. Braun, J.P. Lievremont, and G.S. Bird. 2001. Mechanisms of capacitative calcium entry. J. Cell Sci. 114:2223–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos, J., P.J. DiGregorio, A.V. Yeromin, K. Ohlsen, M. Lioudyno, S. Zhang, O. Safrina, J.A. Kozak, S.L. Wagner, M.D. Cahalan, et al. 2005. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J. Cell Biol. 169:435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sei, Y., M. Takemura, F. Gusovsky, P. Skolnick, and A. Basile. 1995. Distinct mechanisms for Ca2+ entry induced by OKT3 and Ca2+ depletion in Jurkat T cells. Exp. Cell Res. 216:222–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki, F., E.R. Price, D. Milan, and F. McKeon. 1996. Role of kinases and the phosphatase calcineurin in the nuclear shuttling of transcription factor NF-AT4. Nature. 382:370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers, C.L., C.S. Park, J. Lee, C. Feng, C.L. Fuller, A. Grinberg, J.A. Hildebrand, E. Lacana, R.K. Menon, E.W. Shores, et al. 2002. A LAT mutation that inhibits T cell development yet induces lymphoproliferation. Science. 296:2040–2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, H., M. Kurosaki, M. Takata, and T. Kurosaki. 1997. Genetic evidence for involvement of type 1, type 2 and type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in signal transduction through the B-cell antigen receptor. EMBO J. 16:3078–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda, K., and Z.F. Mainen. 1999. Synaptic [Ca2+]: intracellular stores spill their guts. Neuron. 22:427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.S., H. Tu, Z. Wang, and I. Bezprozvanny. 2003. Modulation of type 1 inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor function by protein kinase a and protein phosphatase 1alpha. J. Neurosci. 23:403–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig, M., C. Peinelt, A. Beck, D.L. Koomoa, D. Rabah, M. Koblan-Huberson, S. Kraft, H. Turner, A. Fleig, R. Penner, and J.P. Kinet. 2006. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 312:1220–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.M., J. Buchanan, R.M. Luik, and R.S. Lewis. 2006. Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 174:803–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeromin, A.V., S.L. Zhang, W. Jiang, Y. Yu, O. Safrina, and M.D. Cahalan. 2006. Molecular identification of the CRAC channel by altered ion selectivity in a mutant of Orai. Nature. 443:226–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosuka, T., K. Sakata-Sogawa, W. Kobayashi, M. Hiroshima, A. Hashimoto-Tane, M. Tokunaga, M.L. Dustin, and T. Saito. 2005. Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nat. Immunol. 6:1253–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneshima, H., A. Miyawaki, T. Michikawa, T. Furuichi, and K. Mikoshiba. 1997. Ca2+ differentially regulates the ligand-affinity states of type 1 and type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Biochem. J. 322:591–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z., T. Cai, J. Tian, A.V. Ivanov, D.R. Giovannucci, and Z. Xie. 2005. Na/K-ATPase tethers phospholipase C and IP3 receptor into a calcium-regulatory complex. Mol. Biol. Cell. 16:4034–4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.L., Y. Yu, J. Roos, J.A. Kozak, T.J. Deerinck, M.H. Ellisman, K.A. Stauderman, and M.D. Cahalan. 2005. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 437:902–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]