Abstract

γ-Secretase is responsible for proteolytic maturation of signaling and cell surface proteins, including amyloid precursor protein (APP). Abnormal processing of APP by γ-secretase produces a fragment, Aβ42, that may be responsible for Alzheimer's disease (AD). The biogenesis and trafficking of this important enzyme in relation to aberrant Aβ processing is not well defined. Using a cell-free reaction to monitor the exit of cargo proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), we have isolated a transient intermediate of γ-secretase. Here, we provide direct evidence that the γ-secretase complex is formed in an inactive complex at or before the assembly of an ER transport vesicle dependent on the COPII sorting subunit, Sec24A. Maturation of the holoenzyme is achieved in a subsequent compartment. Two familial AD (FAD)–linked PS1 variants are inefficiently packaged into transport vesicles generated from the ER. Our results suggest that aberrant trafficking of PS1 may contribute to disease pathology.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the presence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in hippocampal regions of the brain. A major constituent of the amyloid plaque is a small Aβ peptide fragment derived from the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP). APP is cleaved along the secretory pathway by several proteases, two of which, the β- and γ-secretases, normally generate a 40-amino acid long Aβ40 peptide. Abnormal cleavage by γ-secretase yields an aggregation-prone 42-amino acid long Aβ42 peptide that builds up over time to form neuritic plaques. Mutations in APP and presenilin 1 and 2 (PS1 and PS2) account for most of the familial forms of AD (FAD), which lead to early onset of the disease. These mutations either enhance the ratio of Aβ42/Aβ40 or increase the level of both Aβ42 and Aβ40 without changing the ratio (for review see Walsh and Selkoe, 2004).

Presenilin (PS) is believed to be the catalytic subunit of γ-secretase. γ-Secretase is a multi-subunit protein complex whose minimal components are nicastrin (NCT), anterior pharynx-1 (APH-1), presenilin enhancer-2 (PEN-2), and PS (Yu et al., 2000; Francis et al., 2002; Goutte et al., 2002; LaVoie et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2003; Takasugi et al., 2003). Other possible regulatory components of γ-secretase, such as CD147 and TMP21, have been reported (Zhou et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2006). Although not essential, these regulator proteins affect Aβ production. Therefore, the assembly and activation of γ-secretase may be linked to processing and misprocessing of APP.

Early secretory compartments such as endoplasmic reticulum (ER), ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC), and cis-Golgi play a critical role in the synthesis, assembly, and quality control inspection of multi-subunit membrane protein complexes (Ellgaard et al., 1999). In the case of γ-secretase, retrieval of unassembled Pen-2 and NCT, subunits of γ-secretase, is regulated by Rer1 at the cis-Golgi (Kaether et al., 2007; Spasic et al., 2007). Down-regulation of Rer1 causes an increase of γ-secretase at cell surface. Thus, abnormal assembly and traffic of γ-secretase in the early secretory pathway may impact γ-secretase function in later compartments.

Proteins traverse the secretory pathway in defined transport carriers, the first of which, COPII vesicles, conveys newly synthesized and assembled proteins from the ER to the ERGIC (Schekman and Orci, 1996). However, because these COPII vesicles are transient, it is difficult to analyze the molecular characteristics of protein intermediates in cells. Such intermediates may be evaluated by generating transport vesicles in vitro. We exploited a biochemical assay to monitor the export of γ-secretase components from the ER (Kim et al., 2005).

COPII proteins (coat protein complex II; Sar1, Sec13/31, and Sec23/24) assemble on the surface of the ER and capture proteins into vesicles at ER exit sites. The selection of cargo proteins at ER export sites is driven by the direct or indirect interaction of cargo proteins with the Sec24 subunit of the coat (Lee et al., 2004). In this paper, we describe the characteristics of the γ-secretase complex as it assembles in COPII vesicles in membranes harboring wild-type (WT) or FAD mutant forms of PS1.

Results

The γ-secretase complex in the COPII vesicle

COPII vesicles budded from microsomal membranes incubated with nucleotide and cytosol as a source of COPII proteins. ER membranes and transport vesicles were separated by differential centrifugation (Kim et al., 2005). As a control, an ER resident protein, ribophorin I, was not released into the slowly sedimenting transport vesicle fraction (Fig. 1 A). In contrast, an ER-to-Golgi recycling protein, p58/ERGIC53/LMAN1, was released into the vesicle fraction in a cytosol- and nucleotide-dependent manner (Fig. 1 A). Furthermore, this cargo release was inhibited by a dominant-negative form (T39N) of Sar1 but not by Brefeldin A (Fig. 1 A; Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200709012/DC1), suggesting that COPII vesicles are responsible for cargo capture.

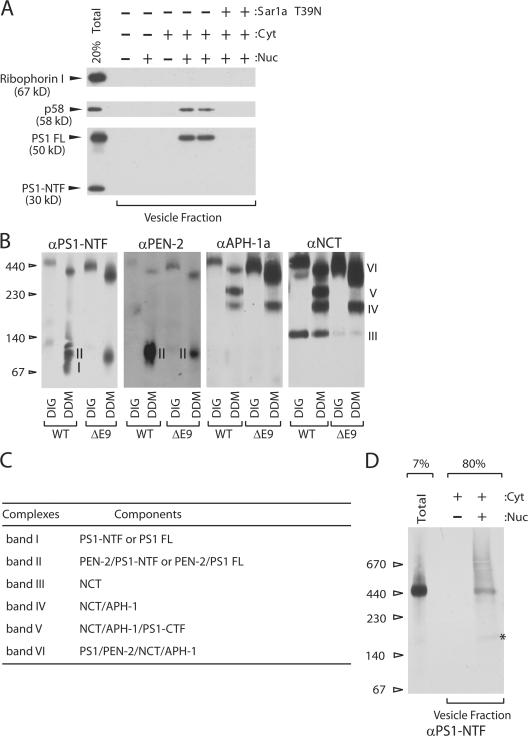

Figure 1.

Packaging of the γ-secretase complex into COPII vesicles. (A) Standard COPII vesicle formation assay. Sar1 T39N is a GDP-restricted form of Sar1a. Cyt represents cytosol (4 mg/ml) and Nuc represents an ATP regenerating system and GTP. (B) Immunoblots of microsomal lysates from N2a cells expressing human PS1 variants. Detergent lysates were analyzed by BN-PAGE and probed for the γ-secretase subunits. Either 1% DIG or 0.5% DDM was used to prepare detergent lysates. Monoclonal anti-NCT antibody (9C3) was used to detect NCT. The contrast of the PEN-2 panel was adjusted to detect faint bands. The specificity of anti-PS1-NTF antibody is shown in Fig. S2 (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200709012/DC1). (C) Constituents of γ-secretase subcomplexes (band I through VI) essentially based on Fraering et al. (2004). (D) A large scale (0.5 ml) vesicle formation reaction was performed using microsomes from N2a cells expressing human WT PS1 and membranes were solubilized with HN buffer containing 1% DIG for BN-PAGE. Polyclonal anti-PS1 NTF antibody was used to detect PS1. The asterisk represents a PS1-containing subcomplex.

To study incorporation of PS1 into the γ-secretase complex, we first analyzed γ-secretase from the microsomal membranes. For γ-secretase complex analysis, digitonin (DIG) or n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM) was used to solubilize microsomes from N2a cells stably expressing PS1 WT or PS1 ΔE9, a FAD-linked mutation (Crook et al., 1998). The resultant mixtures were subject to BN-PAGE (Fig. 1 B). A summary of γ-secretase subcomplexes is described in Fig. 1 C (Fraering et al., 2004). The γ-secretase complexes (band VI) from DIG-solubilized microsomes migrated more slowly than complexes from DDM solubilized material, but in each case all four γ-secretase subunits were detected at roughly the same electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 1 B, band VI). This differential pattern of migration may be influenced by variable detergent binding. Alternatively, DDM may be harsher than DIG and change subunit stoichiometry. It was reported that DDM disrupts the γ-secretase complex into subspecies (Fig. 1 B) (Fraering et al., 2004). Two principal PS1 WT complexes of ∼440 kD (band VI) and ∼100–120 kD (band II) in DDM-solubilized microsomes represent a full complex (band VI) and a complex (band II) that contains PEN-2 and either PS1-NTF (N-terminal fragment) or PS1 FL (full length), respectively (Fig. 1 B, two left panels, lanes WT DDM) (Fraering et al., 2004). Band II was also observed in DDM-solubilized PS1 ΔE9 microsomes (Fig. 1 B two left panels, lanes ΔE9 DDM). Interestingly, the band II from PS1 WT and ΔE9 microsomes showed similar electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 1 B, two left panels, DDM lanes), whereas the band VI from PS1 WT and ΔE9 microsomes showed a mobility difference of 20–30 kD (Fig. 1 B). It is likely that the difference in electrophoretic migration of the apparently intact PS1 WT and PS1 ΔE9 complexes is a reflection of conformational alterations (Berezovska et al., 2005) or changes in subunit stoichiometry induced by the deletion of exon 9 within the PS1ΔE9 holoprotein.

To discover the biogenic origin of intact γ-secretase complex, we solubilized membranes from microsomes and transport vesicles using 1% DIG and applied cleared soluble samples to blue-native gels. From the transport vesicle fraction, PS1 was detected in a band migrating at a position (440 kD) characteristic of the intact γ-secretase complex (Fig. 1 D) (Edbauer et al., 2002; Kimberly et al., 2003). In addition, some PS1-containing subcomplexes were also found in the vesicle fraction (Fig. 1 D).

PS1 in the vesicle fraction and in the γ-secretase complex was mainly the full-length (FL) precursor form (Fig. 1, A and D). Apparently, association of minimal γ-secretase subunits (PS1, NCT, APH-1, and PEN-2) was not sufficient for efficient endoproteolysis of PS1. Perhaps another influence(s) in a later compartment governs PS1 endoproteolysis (see the PS1 is sorted by Sec24A section). From our results, it is clear that γ-secretase assembly occurs before or within COPII vesicles.

Packaging of the endogenous γ-secretase complex

Overexpression of PS1 may bias formation of the γ-secretase complex in the ER or COPII vesicles. To test whether the endogenous level of PS1 leads to formation of γ-secretase, we used CHO-K1 cells where PS1 FL is relatively easily detectable (Kim et al., 2005). The vesicle fraction contained almost exclusively PS1 FL and was enriched in a higher mobility form of NCT (Fig. 2 A). This higher mobility species of NCT predominated in PS1/2 null ES cells, thus it likely corresponds to the immature form (Fig. 2 B). When the vesicle fraction was analyzed by BN-PAGE to monitor γ-secretase, PS1 was found in band V and VI (Fig. 2 C), reinforcing the idea that normal levels of γ-secretase subunits assemble in an intact complex.

Figure 2.

Packaging of the endogenous γ-secretase complex into COPII vesicles. A cell line derived from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) was used for the transport vesicle formation assay. (A) Standard transport vesicle formation assay. PS1 and NCT were found either as full-length (FL) or immature form in the vesicle fraction, respectively. (B) Microsomes were prepared from CHO-K1 cells, mouse embryonic stem cells (ES), and PS1/PS2 double knockout ES cells (PS null) and protein content was separated on 6% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. (C) A large scale (1.5 ml) transport vesicle formation reaction was performed. Total and transport vesicle membranes were solubilized with HN buffer containing 1% DIG, subjected to BN-PAGE and probed with anti-PS1 NTF antibody. PS1 FL was incorporated into a ∼440 kD complex (band VI) or into ∼250–300 kD complexes (band V). Band V was also recognized by anti-PS1-NTF antibody in CHO-K1 cells lysates but not in N2a cell lysates (Fig. 1 B)

PS1 is sorted by Sec24A

We have previously reported that recombinant mammalian COPII proteins, though functional in budding vesicles from synthetic liposomes, appear to be less active in budding transport vesicles from ER membranes (Kim et al., 2005). A limiting cytosolic factor restores the activity of COPII proteins on ER membranes. This limitation was overcome in incubations containing two- to threefold more than the normal level of ER membranes (semi-intact cells, SICs) (Fig. 3 A). To explore the COPII subunit preference for various cargo proteins, we purified all four human Sec24 proteins in complex with Sec23A (23A/24A, 23A/24B, 23A/24C, and 23A/24D) and used them in reactions containing an elevated level of ER membrane material. As previously seen, the recombinant COPII proteins showed lower cargo packaging activity than cytosol even though ∼10-fold more COPII protein was added to the reactions (Fig. 3 A). p58/ERGIC53/LMAN1 was captured preferentially by Sec24A and Sec24D. APP was recognized by Sec24A, Sec24C, and Sec24D. In contrast, PS1 was favored by Sec24A, although Sec24B and Sec24D were marginally active in PS1 packaging (Fig. 3 A)

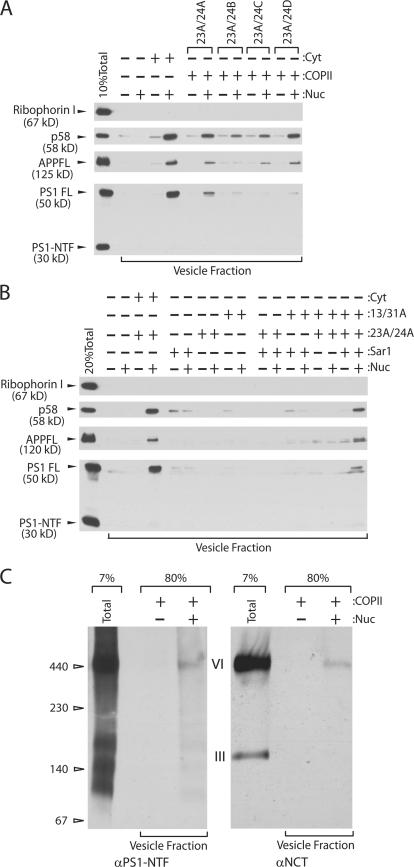

Figure 3.

Cargo specificity of Sec24 paralogues. (A and B) Transport vesicle formation reactions were performed using either rat liver cytosol or recombinant COPII proteins with N2a APPswe PS1 WT cells. The final concentration of Sar1, Sec23/24, and Sec13/31 was 5 μg/ml, respectively. (C) Membranes were solubilized in HN buffer containing 1% DIG and the cleared lysates were applied to BN-PAGE. The contents of the gel were transferred into a PVDF membrane and probed with either anti-PS1-NTF or anti-NCT antibody.

PS1 packaging in authentic COPII vesicles should depend on all of the COPII components. Individual COPII components or combinations of two components did not show significant cargo packaging activity (Fig. 3 B). γ-Secretase packaging into vesicles generated with purified COPII (including 23A/24A) proteins was evaluated in 1% DDM samples resolved on BN-PAGE (Fig. 3 C). PS1 in the vesicle fraction was found in the γ-secretase complex (band VI) which also co-migrated with the NCT subunit (Fig. 3 C, left and right panels). Because Sec24 appears to confer cargo specificity to the COPII coat (Miller et al., 2003; Mossessova et al., 2003), Sec24A may contain a recognition site for one or more of the γ-secretase subunits.

We showed that even though γ-secretase formation occurs in the ER or in COPII vesicles, PS1 is found predominantly as FL and suggested that PS1 endoproteolysis occurs at post ER compartments. This model suggests that if we block export of PS1 from the ER, PS1 should remain intact. To test this possibility, we used shRNA transfection to lower the levels of individual Sec24 paralogues (Fig. 4, A and B). A 90% reduction in Sec24A caused a 75% increase in the ratio of PS1 FL/PS1-NTF (Fig. 4, C and D). Sec24C knockdown caused a reproducible but smaller (25%) reduction in PS1 maturation. Our results are consistent with the idea that PS1 endoproteolysis requires traffic to a downstream compartment(s).

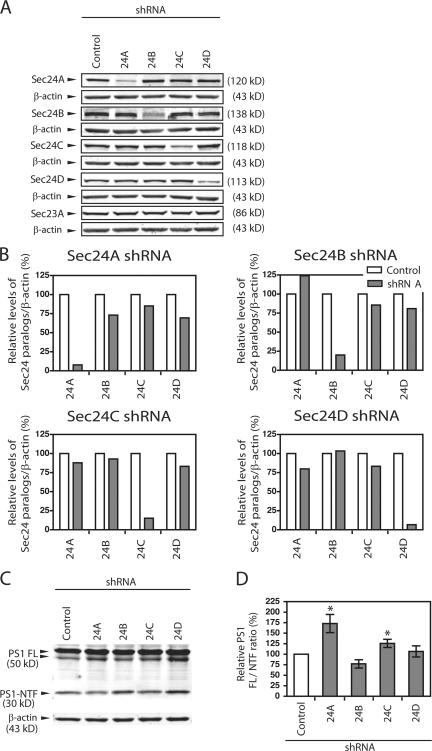

Figure 4.

Sec24A knockdown delays PS1 maturation. (A) HEK 293 cells expressing human APP695 and PS1WT (HEK.APP.PS1 WT) were transiently transfected with 3 μg of shRNA specific for the four individual Sec24 paralogues or the empty vector (control) for 96 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for Sec24A, Sec24B, Sec24C, Sec24D, and Sec23A levels by immunoblotting. Each membrane was probed for β-actin as a loading control. (B) Immunoblot signals derived from IRDye-labeled secondary antibodies were measured using the Odyssey IR Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). Protein levels of the corresponding Sec24 variants were normalized to that of β-actin. Specific reduction due to RNA interference was routinely less than 20% after 96 h shRNA treatment. (C) HEK.APP.PS1 WT cells were transiently transfected with Sec24 paralogue-specific shRNA for 96 h as described above. The full-length form of PS1 (PS1 FL) and the PS1 N-terminal fragment (PS1-NTF) levels were detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-PS1-NTF antibody. (D) Quantification of the maturation level of PS1 FL into PS1-NTF using the Odyssey IR Imaging System after knockdown of individual Sec24 variants. The ratio of PS1 FL to PS1-NTF expressed as percentage of the empty vector control was shown. Error bars represent SD. *, P < 0.05 using t test. n = 3 or 4.

In vitro maturation of γ-secretase

Having established that γ-secretase assembly occurs before or within a COPII vesicle, we explored PS1 endoproteolysis as a surrogate marker of γ-secretase activity because only processed PS1 fragments bind γ-secretase inhibitors (Esler et al., 2000; Li et al., 2000; Seiffert et al., 2000; Beher et al., 2003). We solubilized a total membrane fraction in 0.5% CHAPSO lysis buffer, incubated cleared lysate fractions at 37°C for 0–3 h, and analyzed PS1 maturation by SDS-PAGE. PS1-NTF was generated within 1 h of incubation at pH 6.5, suggesting that a slightly acidic environment is optimal for endoproteolysis of PS1 (Fig. 5 A). A concurrent increase of newly generated PS1-CTF was not observed (Fig. 5 A). Perhaps PS1-CTF was generated quickly and then degraded such that it did not accumulate during the incubation.

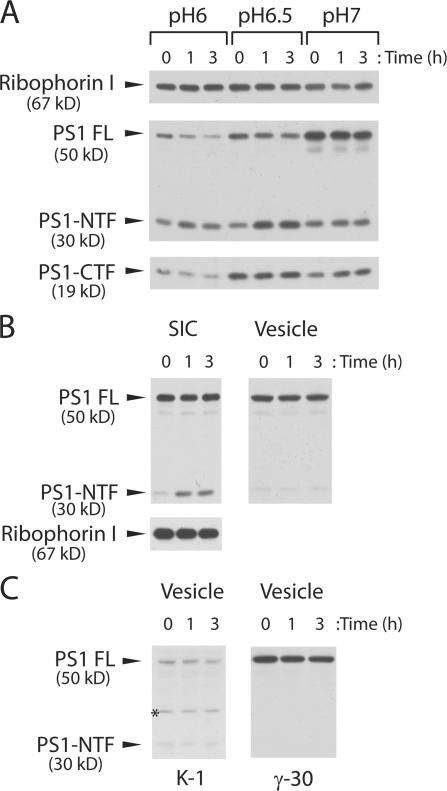

Figure 5.

In vitro PS1 maturation. (A) Permeabilized lysates derived from N2a cells expressing PS1 were solubilized in MNM buffers containing 0.5% CHAPSO at different pHs. Ribophorin I was also probed as a loading control. (B) CHAPSO lysates were prepared from N2a SICs expressing PS1 (SIC) and from COPII vesicles generated from the same cells (Vesicle) (800 μl reaction). Ribophorin I was also probed as a loading control. (C) CHAPSO lysates were prepared from COPII vesicles generated from CHO-K1 cells (K-1) and from γ-30 cells expressing PS1, PEN-2, APH-1a, and NCT (γ-30) (800 μl reaction).

We then examined PS1 maturation in enriched COPII vesicles (Fig. 5, B and C). We prepared CHAPSO lysates using COPII vesicles generated from N2a cells overexpressing PS1 (Fig. 5 B; Vesicle), from CHO-K1 cells containing endogenous level of γ-secretase subunits (Fig. 5 C; K-1) or from γ-30 cells overexpressing PS1, NCT, PEN-2, and APH-1a (Fig. 5 C; γ-30) (Kimberly et al., 2003). Little if any PS1 proteolysis was observed in these samples. Our results suggest that the apparently intact γ-secretase complex formed in ER is not enzymatically competent. Traffic of γ-secretase to the Golgi may provide an environment (pH, ionic) conducive to endoproteolysis or expose the complex to another protein that promotes endoproteolysis.

Quality control at the ER exit site

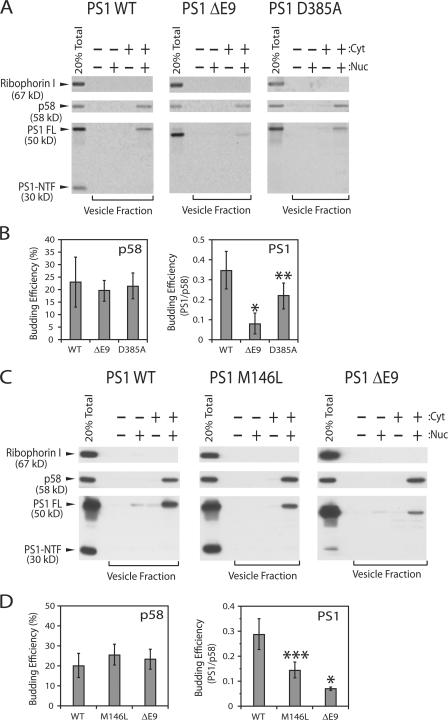

Over 100 FAD-linked PS mutations have been found throughout the PS molecule, especially in PS1 (Alzheimer Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia Mutation database; http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/ADMutations). Many of these mutations affect the folding of PS1 (Berezovska et al., 2005), and yet the mutant proteins promote aberrant APP processing in the secretory stations subsequent to the ER. It is reasonable to assume that these mutant proteins fold sufficiently well to pass ER quality control inspection. Because ER export is a benchmark of underlying ER quality controls, we directly monitored exit of these mutant proteins from the ER using in vitro COPII vesicle formation assay. We used microsomes derived from N2a cell lines stably expressing human APP695swe, a FAD-linked APP variant, and human PS1 variants (Fig. 6, A and B). To account for differences in cargo packaging between experiments, we normalized the packaging efficiency of each cargo molecule to that of p58 in the same reaction (Fig. 6, B and D). As we showed earlier using microsomes from CHO-K1 cells (Fig. 2 A), WT PS1 was found mainly as a full-length form in the transport vesicle fractions (Fig. 6). PS1 ΔE9, a deletion of exon 9 isolated from a family with early onset AD (Crook et al., 1998), showed reduced packaging into COPII vesicles. PS1 D385A, a putative active site mutant, showed a partial defect in the packaging PS1. In all cases, p58 packaging was normal, thus the PS1 ΔE9 packaging defect was cargo selective.

Figure 6.

Defective packaging of FAD-linked PS1 variants into transport vesicles. Transport vesicle formation reactions were performed using microsomes derived from N2a cells stably expressing human APP695swe and human PS1 variants (A and B) or N2a cells stably expressing human APP695wt and human PS1 variants (C and D). See Materials and methods for details. Proteins were visualized using 35S-labeled secondary antibody (A) or using protein A-HRP conjugate for ECL-Plus (Amersham Biosciences) (C). Cyt represents cytosol (4 mg/ml) and Nuc represents an ATP regenerating system and GTP. Error bars represent SD. *, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.01 using t test. n = 5 or 6.

We considered the possibility that the APP695swe mutation may contribute to the abnormal trafficking PS1. To test this idea, we prepared microsomes from N2a cell lines stably expressing human wild-type APP695 and one of three human PS1 variants. Packaging defects for PS1 ΔE9 and PS1 M146L, another FAD-linked PS1 mutation, were obvious although PS1 ΔE9 displayed a more pronounced lesion (Fig. 6, C and D). One other PS1 allele, C410Y, was not detectably different from WT (unpublished data). We conclude that two FAD-linked PS1 mutations, ΔE9 and M146L, are sufficiently defective to impose a quality control delay in ER export of the misfolded forms of PS1.

Incorporation of newly synthesized PS1 into the transport vesicle

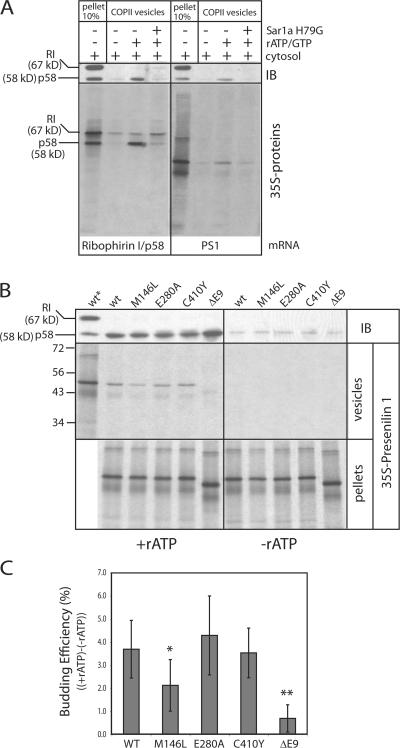

To explore the earliest events in the synthesis, folding and packaging of wild-type and mutant PS1, we adapted our budding reaction to measure the incorporation of membrane proteins synthesized and assembled in vitro. A proof of principle is shown in Fig. 7 A (left) in which both p58 and ribophorin I proteins were synthesized and translocated into permeabilized cells. Packaging of radiolabeled p58 into COPII vesicles was prevented by incubation with the dominant-negative Sar1a H79G. A low level of newly synthesized ribophorin I was released in the vesicle fraction in an incubation with or without Sar1a H79G. This was not observed for steady-state ribophorin I levels analyzed by immunoblot on the same PVDF membrane (Fig. 7 A, top panels). Importantly, radiolabeled wild-type PS1 was packaged into COPII vesicles, although less efficiently than p58 (Fig. 7 A, right).

Figure 7.

Reduced COPII export of newly synthesized FAD mutant PS1 M146L and PS1 ΔE9. (A) Both ribophorin I (RI) and p58 (left) or PS1 (right) proteins were translated in vitro and translocated into the ER membranes of semi-intact N2a cells (SICs). The SICs containing the radiolabeled proteins were harvested and supplemented with components to reconstitute COPII budding. Differential centrifugation separated SIC-ER pellet (input) from the COPII vesicles budded from the ER. After first analyzing the controls for ER export (Ribophorin I and p58) at steady-state levels using immunoblot (IB) analysis, the PVDF membranes were dried and exposed to film and a Phosphorscreen to analyze the radiolabeled proteins. (B) Same as in (A) but for wild-type PS1 and several FAD mutant proteins. Lanes indicated with an asterisk indicate the ER pellet fraction (input). (C) Quantification of wild-type PS1 export and FAD mutant proteins (see Materials and methods). The nonspecific leakage (-rATP, vesicle fractions) was subtracted from the COPII export from ER samples (+rATP,vesicle fractions). Only M146L and ΔE9 showed a significant difference compared with WT (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 using t test. n = 4 to 7).

We quantified the efficiency of wild-type and mutant PS1 protein export comparing radiolabel signal in ER membrane pellet and vesicle fractions (Fig. 7 B, middle and bottom). Quantification showed that PS1 ΔE9 export was reduced almost to background levels, whereas PS1 M146L displayed an intermediate defect (Fig. 7 C). The export of FAD mutants PS1 E280A and C410Y was comparable to wild-type levels. From these results we concluded that the export defects of newly synthesized PS1 ΔE9 and PS1 M146L are comparable to the export defects observed in N2a cells stably expressing these FAD-linked mutant proteins as shown in Fig. 6. Thus, the defect is not the result of overexpression of a mutant protein.

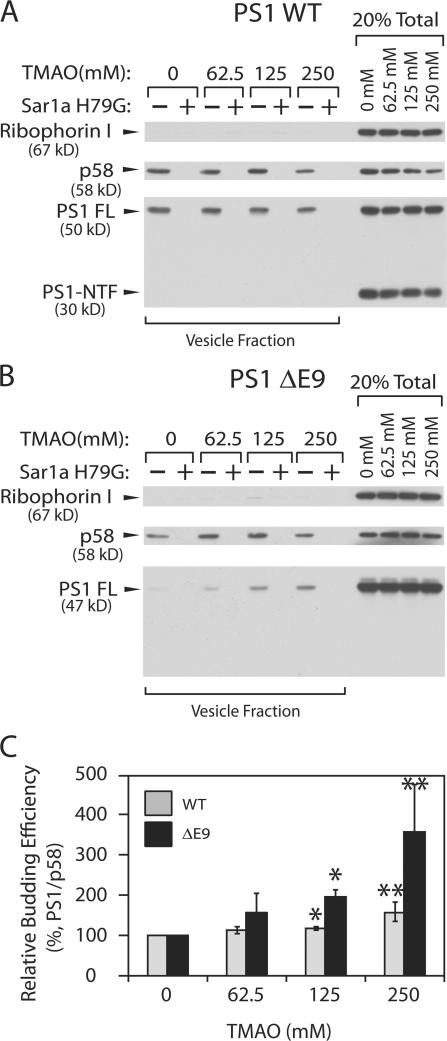

A chemical chaperone, TMAO, partially restores packaging of PS1 ΔE9

Protein misfolding accounts for aberrant export of mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) molecules from the ER (Cheng et al., 1990; Gelman and Kopito, 2002; Sanders and Myers, 2004). Impaired trafficking of CFTR ΔF508 is partially rescued by incubating cells with media containing chemical chaperones such as glycerol and trimethyamine N-oxide (TMAO) (Brown et al., 1996; Sato et al., 1996; Qu et al., 1997; Bennion and Daggett, 2004). To test the idea that the export defect of PS1 ΔE9 is due to misfolding, we performed a transport vesicle formation assay in the presence of increasing concentrations of TMAO (Fig. 8). In addition, to be certain that our reactions recapitulate COPII vesicle formation, we performed control reactions supplemented with a purified dominant-negative Sar1a H79G, to specifically inhibit the generation of COPII vesicles. Packaging of PS1 ΔE9 was increased significantly by addition of TMAO in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 8, B and C). The packaging of WT PS1 was only marginally enhanced by TMAO (Fig. 8, A and C). These results are consistent with the notion that the underlying cause of the trafficking defect is at least partly due to protein misfolding. Because TMAO did not fully repair the packaging defect of PS1 ΔE9, it is possible that the exon 9 region may contain export information.

Figure 8.

TMAO enhances packaging of PS1 ΔE9 into COPII vesicles. (A and B) Microsomes were washed with reaction buffer containing the indicated concentrations of TMAO. Sorbitol was omitted in the buffer to accentuate the effect of TMAO. Vesicle formation reactions were performed in the presence of TMAO as indicated. Sar1a H79G (10 μg/ml) was added to the reaction where indicated. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by ECL-plus. (C) For quantification, 35S-labeled secondary antibody was used as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Although the budding efficiency of PS1 WT and ΔE9 is quite different at 0 mM TMAO, it is set to 100% to contrast the effect of TMAO on the two proteins. Error bars represent SD. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.05 using t test. n = 3.

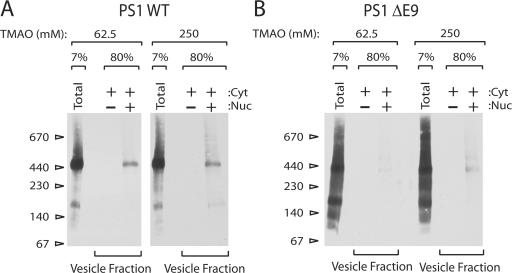

Next, we tested the effect of TMAO on the packaging of the γ-secretase complex bearing PS1 ΔE9. Because addition of 62.5 mM TMAO in the reaction enhanced the overall budding efficiency, we compared 62.5 mM TMAO and 250 mM TMAO conditions where only packaging of PS1 differed (Fig. 8 B, compare 0 and 62.5 mM TMAO conditions). Little or no complex was detected in transport vesicles produced from ΔE9 microsomes at 62.5 mM TMAO condition as expected. Packaging of apparently intact γ-secretase complex was enhanced by 250 mM TMAO from ΔE9 microsomes, whereas packaging of the WT complex was essentially unaffected (Fig. 9, A and B). This result suggests that rescued PS1 ΔE9 is incorporated into the complex.

Figure 9.

TMAO rescues packaging of the Δ-secretase complex containing PS1 ΔE9. N2a APPswe PS1 WT or PS1 ΔE9 cells were used. (A and B) Transport vesicle formation reactions were performed and membrane fractions were analyzed by BN-PAGE as indicated in the legend of Fig. 3. Membranes were solubilized in HN buffer containing 1% DIG. Polyclonal anti-PS1 NTF antibody was used to detect PS1.

Discussion

We report that an apparently immature γ-secretase complex containing intact PS1 is captured in ER-derived COPII vesicles through the intervention of the sorting subunit Sec24A. In vitro PS1 maturation assays suggest that endoproteolysis occurs later in an acidic compartment(s) after a conformational change. Two FAD-linked PS1 alleles, ΔE9 and M146L, retard the packaging of PS1 and the γ-secretase complex. A chemical chaperone, TMAO, restores packaging of PS1 ΔE9, suggesting that this defect is partly due to protein misfolding. Because ER-retained γ-secretase is enzymatically incompetent, ER retention of the complex, per se, cannot directly influence cleavage preference either at the Aβ40 or Aβ42 site.

COPII cargo recognition and sorting is achieved in large measure by the Sec24 subunit (Miller et al., 2003; Mossessova et al., 2003). Mammalian cells have four Sec24 variants (Sec24A, B, C, and D), which show partially overlapping cargo preferences. Despite this redundancy, PS1 showed preference for Sec24A in vitro and in cultured cells (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). This cargo preference suggests that there will be other cargo proteins whose export from the ER depends solely on a particular Sec24 protein. In yeast, Pma1 export depends on Lst1, a Sec24 paralogue (Roberg et al., 1999; Shimoni et al., 2000). The expression pattern of Sec24 proteins may vary in cell types and during developmental stages. Therefore, spatiotemporal regulation of expression of Sec24 paralogues may be coupled with expression of PS1 to facilitate development.

Membrane protein mutations are a common cause of human disease. In the case of cystic fibrosis conductance regulator (CFTR), over 1,200 cystic fibrosis (CF)–causing mutations have been classified (Gelman and Kopito, 2002): class I mutations abrogate synthesis of the CFTR protein, class II mutations cause defective protein trafficking, class III mutations lead to unstable or nonfunctional protein at the cell surface, and class IV mutations interfere with channel activation and regulation by physiological agonists. The CFTR ΔF508 mutation, which causes misfolding and arrests traffic in the ER, is the most common human allele (more than 90%) (Kerem et al., 1989; Riordan et al., 1989). The CFTR ΔF508 mutation was initially believed to affect trafficking alone (for review see Gelman and Kopito, 2002). However, the folding defect also produces an abnormal response to β-adrenergic agonists and instability at the plasma membrane. Incubation of cells expressing CFTR ΔF508 in a medium containing osmolytes such as glycerol and TMAO increases the steady-state localization of functional CFTR ΔF508 in the plasma membrane (Brown et al., 1997). Unfavorable interaction between osmolytes and the peptide backbone favors the folded state in normal and misfolded mutant proteins (Bolen and Baskakov, 2001). The effect of TMAO on traffic of the PS1 ΔE9 mutant protein resembles the behavior of CFTR ΔF508 mutant protein, thus PS1 misfolding causes pleiotropic effects such as a trafficking defect and abnormal processing of APP.

Misfolded proteins in the ER are subjected to quality control and in severe cases to ER associated degradation (ERAD) (Römisch, 2005). Although the deletion mutant PS1 ΔE9 is profoundly defective in ER export, the mutant protein is as stable as PS1 WT (Ratovitski et al., 1997). In fact, the steady-state distribution of PS1 ΔE9 is only mildly different from that of PS1 WT (Kim et al., 2000). Although the ΔE9 mutant protein is substantially defective in sorting into COPII vesicles in vitro, this delay is overcome with time and the mutant protein is eventually targeted to later compartments. Delays at later stations may have a direct bearing on the misprocessing of APP in cells harboring ΔE9 or other FAD mutant proteins.

Previous studies suggest that formation of the γ-secretase complex can occur in the ER (Kim et al., 2004; Capell et al., 2005). These studies used a recombinant NCT construct with an ER-retrieval motif (KKXX) inserted into the cytosolic portion of NCT in order to retain NCT in the ER. In cells in which the normal NCT was down-regulated, the ER-retained NCT was incorporated into the γ-secretase complex and generated Aβ at a normal level, suggesting that the active γ-secretase complex formation can happen in the ER. However, because the ER-retrieval signal exerts its effect through retrieval rather than inhibition of ER export, it is not clear where activation of the γ-secretase complex occurs. For example, it is possible that γ-secretase is assembled and activated in the ERGIC or in the cis-Golgi and retrieved back to ER. In our study, we monitored the content of ER derived vesicles directly. In addition, normal levels of endogenous PS1 were detected in the γ-secretase complex packaged in ER-derived vesicles.

We discovered that complex formation and activation of this proteolytic enzyme are discrete processes. A conformational change and an acidic environment may be critical requirements for maturation of γ-secretase under normal conditions. Our data suggest that this process occurs at a post-ER compartment(s). Consistent with this model, it is reported that the ER form of NCT is sensitive for trypsin treatment whereas complex glycosylated NCT is resistant (Shirotani et al., 2003). Our results indicate that an acidic environment is not sufficient for γ-secretase activation.

Retention of mutant γ-secretase in the ER may have direct or indirect consequences that influence the development of AD. For example, PS1 may serve as a Ca2+ leak channel in the ER. Disturbance of Ca2+ homeostasis in cells expressing the two FAD-linked PS1 mutations (ΔE9 and M146V) may be the consequence of ER retention (Tu et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2007). Alternatively, in light of the recent finding that PS has a γ-secretase–independent function in cytoskeletal organization, it is also possible that an ER export delay of γ-secretase or PS1 may disturb cytoskeleton-mediated traffic at later compartments (Khandelwal et al., 2007).

Our results suggest a model in which γ-secretase is assembled in the ER and activated in a downstream acidic compartment. A delay in ER export of the γ-secretase complex may play a role in the disruption of cell physiology.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Antibodies were used as described earlier (Kim et al., 2005). Antibodies were diluted as follows: anti-Sec24A antibody, 1:1,000; anti-Sec24B antibody, 1:1,000; anti-Sec24C antibody, 1:1,000; anti-Sec24D antibody, 1:1,000; anti-Sec23 antibody, 1:1,000; anti-actin C4 antibody (Mab), 1:20,000 (MP Biomedicals); anti-PS1 NTF (Ab14), 1:10,000 (a gift from Sam Gandy, Farber's Institute of Neuroscience, Philadelphia, PA); anti-NCT antibody (Guinea pig), 1:2,000 (Chemicon); mouse monoclonal anti-NCT antibody (9C3), 1: 7,000; mouse monoclonal anti-PEN-2 antibody (7D3), 1:9,000; polyclonal anti-APH1a antibody (B80.2), 1:1,000. Anti-NCT antibody, anti-PEN-2 antibody, and anti-APH1a antibodies were gifts from W. Annaert (Center for Human Genetics, Leuven, Belgium).

Plasmid constructions

The human Sec24A coding region was amplified from MGC-12985 (ATCC) using synthetic oligonucleotides JK108 (5′-CCTTCCAACCCCATGGGAATGTCCCAGCCGGGAATACCGGCC-3′) and JK109 (5′-TTTTTTTTGTGCGGCCGCAAATTTTATTTCACATTAAGTCAGTAT-3′). The amplified fragments were digested with NcoI and NotI and inserted into corresponding sites of pHis-hSec24C to replace Sec24C with Sec24A. The resultant plasmid, pJK13s, has a His6 tag at the N terminus, and the C-terminal region is truncated. To construct the full-length Sec24A, we digested pJK13s and pBS-hSec24A (J.-P. Paccaud) with StuI and XhoI. The StuI- and XhoI-digested fragment from pBS-hSec24A containing an intact Sec24A C-terminal region was inserted into the corresponding site of pJK13s to generate a full-length human Sec24A (pJK13). The sequence of this resultant Sec24A is identical to AAH19341.

The human Sec24B coding region was amplified from pCiNeo-Flag-human Sec24B using synthetic oligonucleotides JK110 (5′-TACAAAGACGCCATGGGAATGTCGGCCCCCGCCGGGTCCTCTCAC-3′) and JK111 (5′-GTCTGCTCGAAGCATTAACCCTCA-3′). The amplified fragments were digested with NcoI and NotI and inserted into corresponding sites of pHis-hSec24C to replace Sec24C with Sec24B. This plasmid, pJK14, has a His6 tag at the N terminus.

The human Sec24D coding region was amplified from MGC-46092 (ATCC) using synthetic oligonucleotides JK114 (5′-TGGAATGATAGAATTCAAATGAGTCAACAAGGTTACGTGGCTACA-3′) and JK113 (5′-TTTTTAAGAGCGGCCGCAGTGATTTATTGATACTGGTTAACA-3′). The amplified fragments were digested with EcoRI and NotI and inserted into corresponding sites of pHis-hSec24C to replace Sec24C with Sec24D. This plasmid, pJK15, has a His6 tag at the N terminus.

Plasmids pHis-hSec24C, pJK13, pJK14, and pJK15 are derivatives of pFastBac HTb (Invitrogen) suitable for baculoviral manipulation.

Expression and purification of proteins

Rat liver cytosol was prepared as described previously (Kim et al., 2005). Hamster SarA2 (previously known as Sar1a) protein, Sec23A/24, and Sec13/31A complexes were also purified as described previously (Kim et al., 2005). Sf9 cells infected with either Sec23A/His6Sec24C or Sec13/His6Sec31A viruses were lysed by sonication in a lysis buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 500 mM KOAc, 250 mM sorbitol, 10% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, 0.1 mM EGTA, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol] supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (1×, Roche). The lysate was cleared by successive centrifugation in a Sorvall SS34 rotor for 30 min at 15,000 rpm and in a Beckman 45 Ti rotor for 1 h at 40,000 rpm. The cleared lysate was incubated with prewashed Ni-agarose resin for 1 h at 4°C and poured into a column. The column was washed first with lysis buffer and washing buffer (lysis buffer with 50 mM imidazole) and then with elution buffer (lysis buffer with 250 mM imidazole). Eluates were pooled, distributed into small aliquots, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80°C.

Cell culture

N2a cells stably expressing human APP695 were transfected with pAG3-PS1WT, or pAG3-PS1M146L or pAG3-PS1ΔE9 plasmid and selected in a medium containing 50% DME, 50% OptiMEM, and 5% FBS supplemented with 200 μg/ml G418 and 400 μg/ml zeocin. N2a cells were transfected with pAG3-PS1WT or pAG3-PS1ΔE9 plasmid and selected in a medium containing 50% DME, 50% OptiMEM, and 5% FBS supplemented with 400 μg/ml zeocin. Colonies derived from single cells were screened for similar levels of PS1 expression (∼15-fold more than endogenous mouse PS1, probably an overestimation because anti–human PS1 NTF antibody was used to quantify signals). Human embryonic kidney (HEK 293) cells stably expressing human APP695 (HEK.APP) were maintained in DME supplemented with 1× NEAA, 10% FBS, and 400 μg/ml G418. HEK 293 cells stably expressing both human APP695 and PS1WT (HEK.APP.PS1 WT) were maintained in DME supplemented with 1× NEAA, 10% FBS, 550 μg/ml G418, and 400 μg/ml hygromcyin. CHO-K1 cells were maintained as described previously (Kim et al., 2005). γ-30 cells were a gift from Dr. Michael Wolfe (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA).

In vitro vesicle-formation assay

Microsomes, rat liver cytosol, and recombinant COPII proteins were prepared as described previously (Kim et al., 2005). A microsome suspension (30 μl) was mixed in 500 μl reaction buffer for the measurement of absorbance (600 nm). Normally, at an A600 = 0.025, 30 μl of the original microsome suspension was used for a 100-μl budding reaction. When semi-intact cells (SICs) were used instead of microsomes, a suspension (5 μl) was mixed in 500 μl reaction buffer for the measurement of absorbance (600 nm). Normally, at an A600 = 0.02, 5 μl of the original SIC suspension was used for a 100-μl budding reaction. For most samples, 20% of total membranes and 75% of a transport vesicle fraction were loaded into a well. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membrane strips were probed with appropriate primary antibodies and 35S-labeled secondary antibody, then quantified and visualized using a Phosphorimager. Radioactive signals were measured to calculate the budding/packaging efficiency of each cargo molecule based on total input and the efficiency of a cargo protein was normalized to the budding efficiency of p58. Because PS1ΔE9 and PS1D385A are not processed into N-terminal and C-terminal fragments (NTF and CTF), we summed the signals of full-length (FL) form and NTF when calculating the total input of PS1WT and PS1M146L for comparison.

In vitro PS1 endoproteolysis assay

The procedure to make SICs has been described (Wilson et al., 1995). 100 μl of standard SICs (see in vitro vesicle-formation assay section) were centrifuged and the pellet was solubilized in a 100 μl MNM (50 mM MES, pH 6.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgOAc) buffer containing 0.5% CHAPSO. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 100,000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was sampled into three tubes (15 μl each) and incubated at 37°C as indicated. After the reaction, samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

In vitro tranlation, translocation, and budding reaction

The procedure to make SICs and the subsequent in vitro translation reactions have been described (Wilson et al., 1995). After translating the proteins for 45 min at 30°C, 0.75 ml ice-cold KHM buffer (110 mM KOAc, 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, and 2 mM Mg(OAC)2) was added to stop the translation reaction and the SICs were harvested at 3,000 g for 3 min at 4°C. The SICs were resuspended in 20 μl KHM and aliquoted before assembling the budding reaction as described above. To calculate the percentage of budding, we correlated the radiolabeled signal in the vesicle fractions (both −rATP and +rATP) to the radiolabeled signal in the ER pellet fractions of each translated protein. Nonspecific leakage found in the vesicle fractions from budding reactions without ATP regeneration mix (−rATP) was subtracted from radiolabeled signal found in vesicle fractions from budding reactions with ATP regeneration mix (+rATP).

Blue-native PAGE

Membranes were solubilized with HN buffer containing 50 mM Hepes (7.0), 50 mM NaCl, and appropriate detergents for 30 min at 4°C. Lysates were centrifuged for 30 min at 65,000 rpm in a Beckman TLA100.3 rotor and separated on 4–12.5% polyacrylamide gradient gels (18 cm × 16 cm × 1.5 mm) with high molecular weight markers from Amersham Biosciences (Schägger and von Jagow, 1991).

RNA interference

The coding regions of human Sec24A, Sec24B, Sec24C, and Sec24D were used to design short hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs for specific gene silencing of the corresponding Sec24 isoforms using the siRNA Target Finder software from Ambion (http://www.ambion.com/techlib/misc/siRNA_finder.html). The shRNA target sequences for individual human Sec24 isoforms were as follows: 5′-AGGAGATGGAAGTGTAACT-3′ (Sec24A), 5′-GGCATTGGTACCGTGTTAT-3′ (Sec24B), 5′-TGTAGCTTCTCAGTTCACT-3′ (Sec24C), and 5′-CCCTTTACAAATACAACAA-3′ (Sec24D). Custom-made 62-nt DNA oligonucleotides were designed to contain a 19-nt sense strand target sequence that was linked to the 19-nt reverse complement antisense sequence by a short spacer region (5′-TTCAAGAGA-3′), followed by the RNA polymerase III termination sequence (5′-TTTTTT-3′), with the addition of BglII and BamHI restriction enzyme sites flanking the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. A pair of complementary oligonucleotides for each Sec24 target was synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies), as follows: 5′-GATCAGGAGATGGAAGTGTAACTTTCAAGAGAAGTTACACTTCCATCTCCTTTTTTTGGAAA-3′ and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAAAGGAGATGGAAGTGTAACTTCTCTTGAAAGTTACACTTCCATCTCCT-3′ for Sec24A;5′-GATCGGCATTGGTACCGTGTTATTTCAAGAGAATAACACGGTACCAATGCCTTTTTTGGAAA-3′ and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAAGGCATTGGTACCGTGTTATTCTCTTGAAATAACACGGTACCAATGCC-3′ for Sec24B; 5′-GATCTGTAGCTTCTCAGTTCACTTTCAAGAGAAGTGAACTGAGAAGCTACATTTTTTGGAAA-3′ and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAATGTAGCTTCTCAGTTCACTTCTCTTGAAAGTGAACTGAGAAGCTACA-3′ for Sec24C; 5′-GATCCCCTTTACAAATACAACAATTCAAGAGATTGTTGTATTTGTAAAGGGTTTTTTGGAAA-3′ and 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAACCCTTTACAAATACAACAATCTCTTGAATTGTTGTATTTGTAAAGGG-3′ for Sec24D.The complementary pair of DNA oligonucleotides was annealed and ligated into the linearized pSUPER.retro.puro shRNA expression vector (OligoEngine) in between the BglII and HindIII sites. This shRNA vector is expressed under the control of a human H1 RNA polymerase III promoter, to direct the synthesis of small RNA transcripts that can fold into short hairpin structure.

HEK.APP and HEK.APP.PS1 WT cells were transiently transfected with 3 μg of either pSUPER.retro.puro-Sec24 constructs or pSUPER.retro.puro empty vector as control using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cell lysates were harvested at 96 h post-transfection in cold lysis buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, and 1 mM PMSF] supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche). Equal amounts of total proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Membranes were probed with the appropriate primary antibodies and IRDye labeled secondary antibodies, then visualized and quantified using the LI-COR Odyssey IR Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). The level of β-actin was used as a loading control for each membrane.

Online supplemental material

Figure S1 shows packaging of endogenous cargo proteins from CHO-K1 microsomes. Figure S2 shows that anti-PS1-NTF antibody specifically recognizes PS1 derivatives. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200709012/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Michael Wolfe for providing the γ-30 cell line, to Dr. Sam Gandy for Ab14 antibody, and to Dr. Wim Annaert for NCT, APH, and Pen2 antibodies. We thank members of Schekman laboratory for critical discussion. We thank Ann Fisher in the cell culture facility for technical assistance.

B. Kleizen was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) fellowship. This work was supported by funds provided by the Adler Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to R. Schekman).

J. Kim's present address is Section of Genetics, Department of Pediatrics, M.I.N.D. Institute, University of California-Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, CA 95817.

Abbreviations used in this paper: APP, amyloid precursor protein; COPII, coat protein complex II; CTF, C-terminal fragment; ERGIC, ER-to-Golgi intermediate compartments; FAD, familial Alzheimer's disease; FL, full length; NTF, N-terminal fragment; PS, presenilin; SIC, semi-intact cell; WT, wild type.

References

- Beher, D., M. Fricker, A. Nadin, E.E. Clarke, J.D.J. Wrigley, Y.-M. Li, J.G. Culvenor, C.L. Masters, T. Harrison, and M.S. Shearman. 2003. In vitro characterization of the presenilin-dependent γ-secretase complex using a novel affinity ligand. Biochemistry. 42:8133–8142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennion, B.J., and V. Daggett. 2004. Counteraction of urea-induced protein denaturation by trimethylamine N-oxide: a chemical chaperone at atomic resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:6433–6438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezovska, O., A. Lleo, L.D. Herl, M.P. Frosch, E.A. Stern, B.J. Bacskai, and B.T. Hyman. 2005. Familial Alzheimer's disease presenilin 1 mutations cause alterations in the conformation of presenilin and interactions with amyloid precursor protein. J. Neurosci. 25:3009–3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolen, D.W., and I.V. Baskakov. 2001. The osmophobic effect: Natural selection of a thermodynamic force in protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 310:955– 963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.R., L.Q. Hong-Brown, J. Biwersi, A.S. Verkman, and W.J. Welch. 1996. Chemical chaperones correct the mutant phenotype of the ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1:117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.R., L.Q. Hong-Brown, and W.J. Welch. 1997. Strategies for correcting the delta F508 CFTR protein-folding defect. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 29:491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capell, A., D. Beher, S. Prokop, H. Steiner, C. Kaether, M.S. Shearman, and C. Haass. 2005. γ-secretase complex assembly within the early secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 280:6471–6478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., H. Hasegawa, G. Schmitt-Ulms, T. Kawarai, C. Bohm, T. Katayama, N. Sanjo, M. Glista, E. Rogaeva, Y. Wakutani, et al. 2006. TMP21 is a presenilin complex component that modulates γ-secretase but not ɛ-secretase activity. Nature. 440:1208–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.H., R.J. Gregory, J. Marshall, S. Paul, D.W. Souza, G.A. White, C.R. O'Riordan, and A.E. Smith. 1990. Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell. 63:827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crook, R., A. Verkkoniemi, J. Perez-Tur, N. Mehta, M. Baker, H. Houlden, M. Farrer, M. Hutton, S. Lincoln, J. Hardy, et al. 1998. A variant of Alzheimer's disease with spastic paraparesis and unusual plaques due to deletion of exon 9 of presenilin 1. Nat. Med. 4:452–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edbauer, D., E. Winkler, C. Haass, and H. Steiner. 2002. Presenilin and nicastrin regulate each other and determine amyloid β-peptide production via complex formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:8666–8671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard, L., M. Molinari, and A. Helenius. 1999. Setting the standards: quality control in the secretory pathway. Science. 286:1882–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler, W.P., W.T. Kimberly, B.L. Ostaszewski, T.S. Diehl, C.L. Moore, J.-Y. Tsai, T. Rahmati, W. Xia, D.J. Selkoe, and M.S. Wolfe. 2000. Transition-state analogue inhibitors of γ-secretase bind directly to presenilin-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:428–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraering, P.C., M.J. LaVoie, W. Ye, B.L. Ostaszewski, T. Kimberly, D.J. Selkoe, and M.S. Wolfe. 2004. Detergent-dependent dissociation of active γ-secretase reveals an interaction between Pen-2 and PS1-NTF and offers a model for subunit organization within the complex. Biochemistry. 43:323–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis, R., G. McGrath, J. Zhang, D.A. Ruddy, M. Sym, J. Apfeld, M. Nicoll, M. Maxwell, B. Hai, M.C. Ellis, et al. 2002. aph-1 and pen-2 are required for Notch pathway signaling, γ-secretase cleavage of βAPP, and presenilin protein accumulation. Dev. Cell. 3:85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, M.S., and R.R. Kopito. 2002. Rescuing protein conformation: prospects for pharmacological therapy in cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 110:1591–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutte, C., M. Tsunozki, V.A. Hale, and J.R. Priess. 2002. APH-1 is a multipass membrane protein essential for the Notch signaling pathway in Casenorhabditis elegans embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:775–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaether, C., J. Scheuermann, M. Fassler, S. Zilow, K. Shirotani, C. Valkova, B. Novak, S. Kacmar, H. Steiner, and C. Haass. 2007. Endoplasmic reticulum retension of the γ-secretase complex component Pen2 by Rer1. EMBO Rep. 8:743–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem, B.-S., J.M. Rommens, J.A. Buchanan, D. Markiewicz, T.K. Cox, A. Chakravarti, M. Buchwald, and L.C. Tsui. 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science. 245:1073–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal, A., D. Chandu, C.M. Roe, R. Kopan, and R.S. Quatrano. 2007. Moonlighting activity of presenilin in plants is independent of γ-secretase and evolutionarily conserved. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:13337–13342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., S. Hamamoto, M. Ravazzola, L. Orci, and R. Schekman. 2005. Uncoupled packaging of amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 into coat protein complex II vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 280:7758–7768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-H., J.J. Lah, G. Thinakaran, A. Levey, and S.S. Sisodia. 2000. Subcellular localization of presenilins: association with a unique membrane pool in cultured cells. Neurobiol. Dis. 7:99–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-H., Y.I. Yin, Y.-M. Li, and S.S. Sisodia. 2004. Evidence that assembly of an active γ-secretase complex occurs in the early compartments of the secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279:48615–48619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly, W.T., M.J. LaVoie, B.L. Ostaszewski, W. Ye, M.S. Wolfe, and D.J. Selkoe. 2003. γ–secretase is a membrane protein complex comprised of presenilin, nicastrin, aph-1, and pen-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:6382–6387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVoie, M.J., P.C. Fraering, B.L. Ostaszewski, W. Ye, W.T. Kimberly, M.S. Wolfe, and D.J. Selkoe. 2003. Assembly of the γ-secretase complex involves early formation of an intermediate subcomplex of Aph-1 and nicastrin. J. Biol. Chem. 278:37213–37222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.C.S., E.A. Miller, J. Goldberg, L. Orci, and R. Schekman. 2004. Bi-directional protein transport between the ER and Golgi. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20:87–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.-M., M. Xu, M.-T. Lai, Q. Huang, J.L. Castro, J. DiMuzio-Mower, T. Harrison, C. Lellis, A. Nadin, J.G. Neduvelil, et al. 2000. Photoactivated γ-secretase inhibitors directed to the active site covalently label presenilin 1. Nature. 405:689–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.J., H. Wang, H. Li, B.S. Kim, S. Shah, H.J. Lee, G. Thinakaran, T.W. Kim, G. Yu, and H. Xu. 2003. PEN-2 and APH-1 coordinately regulate proteolytic processing of presenilin 1. J. Biol. Chem. 278:7850–7854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E., T. Beilharz, P. Malkus, M. Lee, S. Hamamoto, L. Orci, and R. Schekman. 2003. Multiple cargo binding sites on the COPII subunit Sec24p ensure capture of diverse membrane proteins into transport vesicles. Cell. 114:497–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossessova, E., L.C. Bickford, and J. Goldberg. 2003. SNARE selectivity of the COPII coat. Cell. 114:483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, O., H. Tu, T. Lei, M. Bentahir, B. De Strooper, and I. Bezprozvanny. 2007. Familial Alzheimer disease-linked mutations specifically disrupt Ca2+ leak function of presenilin 1. J. Neurosci. 117:1230–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu, B.-H., E.H. Strickland, and P.J. Thomas. 1997. Localization and suppression of a kinetic defect in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator folding. J. Biol. Chem. 272:15739–15744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratovitski, T., H.H. Slunt, G. Thinakaran, D.L. Price, S.S. Sisodia, and D.R. Borchelt. 1997. Endoproteolytic processing and stabilization of wild- type and mutant presenilin. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24536–24541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan, J.R., J.M. Rommens, B. Kerem, N. Alon, R. Rozmahel, Z. Grzelczak, J. Zielenski, S. Lok, N. Plavsic, J.L. Chou, et al. 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 245:1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Römisch, K. 2005. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21:435–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberg, K.J., M. Crotwell, P. Espenshade, R. Gimeno, and C.A. Kaiser. 1999. LST1 is a SEC24 homologue used for selective export of the plasma membrane ATPase from the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 145:659–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, C.R., and J.K. Myers. 2004. Disease-related misassembly of membrane proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33:25–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, N., F. Urano, J.Y. Leem, S.H. Kim, M. Li, D. Donoviel, A. Bernstein, A.S. Lee, D. Ron, M.L. Veselits, et al. 1996. Glycerol reverses the misfolding phenotype of the most common cystic fibrosis mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 271:635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schägger, H., and G. von Jagow. 1991. Blue native electrophoresis for isolation of membrane protein complexes in enzymatically active form. Anal. Biochem. 199:223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schekman, R., and L. Orci. 1996. Coat proteins and vesicle budding. Science. 271:1526–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffert, D., J.D. Bradley, C.M. Rominger, D.H. Rominger, F. Yang, J.E. Meredith Jr., Q. Wang, A.H. Roach, L.A. Thompson, S.M. Spitz, et al. 2000. J. Biol. Chem. 274:34086–34091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni, Y., T. Kurihara, M. Ravazzola, M. Amherdt, L. Orci, and R. Schekman. 2000. Lst1p and Sec24p cooperate in sorting of the plasma membrane ATPase into COPII vesicles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 151:973–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirotani, K., D. Edbauer, A. Capell, J. Schmitz, H. Steiner, and C. Haass. 2003. γ–secretase activity is associated with a conformational change of nicastrin. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16474–16477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasic, D., T. Raemaekers, K. Dillen, I. Declerck, V. Baert, L. Serneels, J. Füllekrug, and W. Annaert. 2007. Rer1p competes with APH-1 for binding to nicastrin and regulates γ–secretase complex assembly in the early secretory pathway. J. Cell Biol. 176:629–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasugi, N., T. Tomita, I. Hayashi, M. Tsuruoka, M. Niimura, Y. Takahashi, G. Thinakaran, and T. Iwatsubo. 2003. The role of presenilin cofactors in the γ-secretase complex. Nature. 422:438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu, H., O. Nelson, A. Bezprozvanny, Z. Wang, S.-F. Lee, Y.-H. Hao, L. Serneels, B. De Strooper, G. Yu, and I. Bezprozvanny. 2006. Presenilins form ER Ca2+ leak channels, a function disrupted by familial Alzheimer's disease-linked mutations. Cell. 126:981–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, D.M., and D.J. Selkoe. 2004. Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 44:181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R., A.J. Allen, J. Oliver, J.L. Brookman, S. High, and N.J. Bulleid. 1995. The translocation, folding, assembly and redox-dependent degradation of secretory and membrane proteins in semi-permeabilized mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 307:679–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G., M. Nishimura, S. Arawaka, D. Levitan, L. Zhang, A. Tandon, Y.Q. Song, E. Rogaeva, F. Chen, T. Kawarai, et al. 2000. Nicastrin modulates presenilin-mediated notch/glp-1 signal transduction and βAPP processing. Nature. 407:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S., H. Zhou, P.J. Walian, and B.K. Jap. 2005. CD147 is a regulatory subunit of the γ-secretase complex in Alzheimer's disease amyloid β-peptide production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:7499–7504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]