Abstract

Activation of c-Met, the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/scatter factor receptor induces reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, which drives epithelial cell scattering and motility and is exploited by pathogenic Listeria monocytogenes to invade nonepithelial cells. However, the precise contributions of distinct Rho-GTPases, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases, and actin assembly regulators to c-Met-mediated actin reorganization are still elusive. Here we report that HGF-induced membrane ruffling and Listeria invasion mediated by the bacterial c-Met ligand internalin B (InlB) were significantly impaired but not abrogated upon genetic removal of either Cdc42 or pharmacological inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-kinase). While loss of Cdc42 or PI3-kinase function correlated with reduced HGF- and InlB-triggered Rac activation, complete abolishment of actin reorganization and Rac activation required the simultaneous inactivation of both Cdc42 and PI3-kinase signaling. Moreover, Cdc42 activation was fully independent of PI3-kinase activity, whereas the latter partly depended on Cdc42. Finally, Cdc42 function did not require its interaction with the actin nucleation-promoting factor N-WASP. Instead, actin polymerization was driven by Arp2/3 complex activation through the WAVE complex downstream of Rac. Together, our data establish an intricate signaling network comprising as key molecules Cdc42 and PI3-kinase, which converge on Rac-mediated actin reorganization essential for Listeria invasion and membrane ruffling downstream of c-Met.

Actin reorganization is frequently initiated by ligand binding to growth factor receptors, e.g., receptor tyrosine kinases, such as c-Met (3, 5). Receptor clustering and activation are accompanied by tyrosine phosphorylation and adaptor recruitment required in turn for the activation of small GTPases, such as Rho family members. However, knowledge of the relative relevance of individual GTPases, their respective activators, and their direct and indirect effector complexes is still fragmentary (11).

Rho family small GTPases and of these GTPases, the thoroughly studied members Cdc42 and Rac1 are key signaling switches to actin cytoskeleton reorganization (14, 21, 37). Numerous regulators of actin polymerization were reported to link to these GTPases, including Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) and WASP family and verprolin-homologous protein (WAVE) family members, which are prominent activators of the actin filament-nucleating machine Arp2/3 complex (7, 49). We have recently shown that fibroblasts genetically deleted for Cdc42 have no apparent defects in lamellipodium and filopodium protrusion or in cell migration (12), providing the first direct evidence that Cdc42 is not essential for actin polymerization in cellular protrusions. Nevertheless, constitutively active Cdc42 can drive the formation of conspicuous filopodia (34), although the molecular mechanism of their formation is still unclear (17), since neither its direct interaction partner N-WASP (neural WASP) (32) nor WAVE and Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin assembly are required for this pathway (31, 44, 45). In addition, this GTPase may function in less obvious cytoskeletal rearrangements, such as those elicited during endocytosis or more indirectly, by signal propagation to other Rho family GTPases, such as Rac1 (34).

To obtain more insights into the role of Cdc42 in cytoskeletal rearrangements downstream of the receptor tyrosine kinase c-Met, we have studied both hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-induced membrane ruffling and actin-dependent engulfment of the gram-positive bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. Invasion of this pathogen is mainly brought about by two separable signaling pathways induced by interaction of two bacterial factors, internalin (InlA) and InlB with E-cadherin and c-Met, respectively (36). Since InlA does not interact with murine E-cadherin (28, 40), the engulfment of the wild-type pathogen by murine cell lines compared to isogenic Listeria lacking both internalins is InlB specific. InlB binds and activates c-Met (43), eliciting responses similar to those induced by HGF/scatter factor, including c-Met autophosphorylation, recruitment of signaling adaptors like Gab1, Shc, and Cbl (36), activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) type IA (25, 42), as well as receptor internalization and lysosomal degradation (29). In addition, clathrin-dependent receptor internalization is also thought to power bacterial engulfment (52), although the molecular mechanisms of coordination of the forces generated by both the actin and clathrin machineries are unknown. Here we have focused on defining the precise functions of both Cdc42 and Rac1 GTPases compared to PI3-kinase signaling in stimulating the motogenic output driven by actin polymerization evoked downstream of engagement of the prominent receptor tyrosine kinase c-Met.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies, protein purification, and reagents.

Monoclonal anti-Nap1 antibody (clone 21D12G9; immunoglobulin M) was raised against synthetic peptide NH2-(C)HAVYKQSVTSSA-COOH comprising the 12 C-terminal residues of human and mouse Nck-associated protein 1 (Nap1). Monoclonal anti-Cdc42 (clone 44) and anti-Rac1 (clone 23A8) were purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Heidelberg, Germany) and Biomol (Hamburg, Germany), respectively. Polyclonal anti-N-WASP and isoform-specific WAVE2 antibodies were as described previously (30, 46). Anti-Eps8 (EGF receptor pathway substrate 8) monoclonal antibody (clone 15) was purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Heidelberg, Germany). Anti-Akt and anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Danvers, MA). Mature full-length InlB (amino acid residues 36 to 630) was expressed as a glutathione S-transferase fusion in Escherichia coli BL21, purified by affinity chromatography (glutathione-Sepharose), and cleaved with PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare). Final purification was achieved by gel filtration (Superdex200) in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 500 mM NaCl, dialysis against 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 200 mM NaCl, and subsequent affinity chromatography on heparin Sepharose (Fast Flow) using a linear salt gradient. Chromatography media were from GE Healthcare (Munich, Germany); HGF, epidermal growth factor (EGF), hygromycin, gentamicin, and wortmannin were from SIGMA (Taufkirchen, Germany). LY294002 was from Biosource (Camarillo, CA), FuGene and protease inhibitor cocktail Complete Mini were from Roche (Mannheim, Germany), and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled phalloidin was from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany).

Cells, treatments, and transfections.

The murine control, Cdc42-deficient and Cdc42-deficient fibroblasts reexpressing wild-type Cdc42 (Cdc42wt) were as described previously (12). The parental Cdc42-expressing control cell line (clone 39) was termed Cdc42(fl/−)-C1, and the two independently derived knockout clones 397 and 399 were termed Cdc42(−/−)-KO1 and Cdc42(−/−)-KO2 throughout the paper, respectively. Cdc42-deficient cells stably reexpressing mock plasmid, Cdc42 with F37A mutation (Cdc42F37A) or Cdc42Y40C were generated by infection with retroviruses conferring expression of the respective mutant together with a hygromycin resistance gene as described previously (12) and grown in the presence of 100 μg/ml hygromycin B. Efficient transient expression of Cdc42wt, Rac1wt, or constitutively active Rac1 (Rac1L61) was achieved by transfection with vectors driving bicistronic expression of the respective GTPase and enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) or EGFP (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) alone as a control, followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using a MOFLO sorter (Cytomation). For PAK (p21-activated kinase)-CRIB (canonical Cdc42/Rac interactive binding) pull-down assays, determination of phospho-Akt levels as well as for the induction of membrane ruffling, control, and/or Cdc42 knockout cells were serum starved for 16 to 18 h and treated with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) alone or DMEM containing HGF or InlB for 5 min. For experiments with PI3-kinase inhibition, cells were pretreated for 20 min with LY294002 in concentrations as indicated or wortmannin (100 nM) and then subjected to all assays in the presence of inhibitor. Transfections were done with FuGene according to the manufacturer's instructions. Stable Nap1 knockdown and corresponding control cell lines were described previously (46). The N-WASP-expressing precursor cell line, clone 1, was termed N-WASP(fl/fl)-C1 and the two independently derived knockout clones 1H51 and 1H64 were termed N-WASP(−/−)-KO1 and N-WASP(−/−)-KO2, respectively (31). Immortalized fibroblasts from EGF receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8) knockout mice and corresponding control cells reexpressing myc-tagged Eps8 were grown as described previously (41). WAVE2(−/−) and WAVE2(+/+) cell lines, kindly provided by Tadaomi Takenawa (University of Tokyo, Japan), were maintained as described previously (57).

Bacteria and invasion assay.

Listeria monocytogenes (EGD [wild type]) and the isogenic negative-control strain (ΔInlAB) (35), kindly provided by Juergen Wehland (Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research, Braunschweig, Germany) were grown in brain heart infusion medium and subjected to gentamicin protection assays essentially as described previously (16, 35), with invasion and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) killing times of 1 and 1.5 h, respectively. At least three independent experiments were normalized to an invasion of 1 (100%) in respective control populations as indicated.

Pull-down and PI3-kinase activation assays.

For Rac and Cdc42 activation assays, glutathione S-transferase fused to PAK-CRIB was immobilized on glutathione beads as described previously (46). Fibroblasts grown in 10-cm-diameter dishes were treated as indicated and lysed with 500 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal, 5% sucrose, Complete Mini). GTP-loaded Rac or Cdc42 was precipitated from whole-cell lysates with 30 μl Sepharose beads for 45 to 60 min at 4°C on a rotary wheel. After the beads were washed three times with wash buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Igepal, 5% sucrose), lysates and precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. For quantification of relative Cdc42- or Rac-GTP levels, band intensities were measured by luminometry employing a cooled charge-coupled-device camera (luminescent image analyzer LAS-1000; Fujifilm, London, United Kingdom) and analyzed using AIDA software (Raytest, Germany). Band intensities of active GTPase from at least five independent experiments were each normalized to input (total GTPase), averaged, and expressed as the change in the increase compared to respective mock-treated controls. For assessment of PI3-kinase activity, extracts from starved cells or cells treated with HGF or InlB were subjected to Western blotting using anti-Akt and anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) antibodies and luminometry as described above for Rho-GTPases. Data from at least three independent experiments were expressed as the percentages of phosphorylated Akt of total Akt.

Fluorescence microscopy, assessment of cell morphology, and data analysis.

For quantification of HGF- or InlB-induced ruffling, cells were seeded subconfluently onto glass coverslips, starved, and treated as indicated, fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS, extracted with 0.1% Triton X-100-4% formaldehyde for 1 min, and stained for the actin cytoskeleton with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled phalloidin for 1 h at room temperature. Preparations were analyzed on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 100TV; Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using a 63×/1.4-numerical-aperture plan-apochromatic objective and equipped for epifluorescence as described previously (46). Images were acquired with a back-illuminated, cooled charge-coupled-device camera (TE-CCD 800PB; Princeton Scientific Instruments, Princeton, NJ) driven by IPLab software (Scanalytics Inc., Fairfax, VA). At least 300 cells from three independent experiments for each cell line and experimental condition were manually categorized as indicated. For the EGF experiments shown in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material, cells were treated as described above, except that EGF was employed for both 5 and 10 min.

Data and images were processed using Microsoft Excel 9.0 (Redmond, WA) and Adobe Photoshop 7.0/CS software (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA). Statistical analyses were carried out using SigmaPlot 9.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and Minitab 10.5 (Minitab, State College, PA). Clonal cell lines divided and subjected to different treatments were considered paired data and thus analyzed using paired (one-sample) t test, whereas data sets obtained from different clones or cell lines were compared using unpaired (two-sample) t test.

RESULTS

Cdc42 deficiency impairs InlB-mediated Listeria invasion.

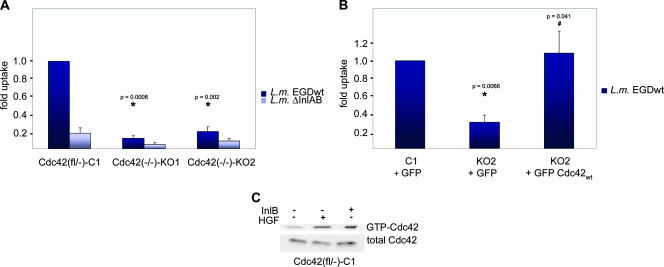

Current models of InlB-mediated Listeria invasion contain numerous key players, many of which are well-established regulators of actin cytoskeleton reorganization, including the Rho family GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 as well as their prominent effectors N-WASP and WAVE (22, 38). However, the relative relevance of the Cdc42 and Rac pathways in InlB-mediated invasion has remained incompletely understood (4). To elucidate a potential role of Cdc42 in this signaling pathway, we performed gentamicin protection assays using two independent Cdc42-deficient cell lines (KO1 and KO2) compared to their parental control line (C1) still expressing functional Cdc42 (12). Interestingly, InlB-specific invasion assessed with wild-type bacteria (L. monocytogenes EGD [wild type]) was strongly reduced (by >70%) upon genetic deletion of Cdc42 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, nonspecific entry as determined with isogenic Listeria lacking both internalin A and B was invariably low in all cell lines (Fig. 1A). More importantly, InlB-specific entry could be fully rescued in Cdc42-deficient cells by transient reexpression of wild-type Cdc42 (Fig. 1B), proving formally that the observed invasion defects were due to the absence of Cdc42. These data demonstrated a significant contribution of Cdc42 to InlB-dependent Listeria invasion and suggested a specific activation of this Rho family GTPase downstream of c-Met engagement by extracellular ligands, such as HGF or bacterial InlB. To test this directly, Cdc42-expressing control cells were treated for 5 minutes with purified HGF or recombinant InlB using concentrations that were established to induce significant reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (20 and 50 ng/ml, respectively, see below) and subjected to Cdc42 activation assay. As expected and consistent with previous observations (56), treatments of these cells (C1) with both HGF (39) and purified InlB resulted in significant activation of this GTPase (Fig. 1C; see also Fig. 7).

FIG. 1.

Cdc42 is required for efficient Listeria uptake. (A) Cdc42-expressing control fibroblasts [Cdc42(fl/−)-C1] and two independent Cdc42-deficient cell lines [Cdc42(−/−)-KO1 and -KO2] were examined for Listeria invasion using a typical gentamicin survival assay with wild-type bacteria (L. monocytogenes EGD wild type [L.m. EGDwt]) and isogenic mutants lacking InlA and InlB (L. monocytogenes ΔInlAB [L.m. ΔInlAB]). Data are expressed as arithmetic means plus standard errors of means (error bars) from at least three independent experiments and normalized to the uptake of wild-type Listeria by Cdc42-expressing controls (C1). Reduction of entry of wild-type bacteria in Cdc42-KO clones compared to control cells was confirmed to be statistically significant as indicated by P < 0.05 (*) using the one-sided t test. (B) Reconstitution of Listeria invasion by transient reexpression of Cdc42. Control (C1) and Cdc42 knockout cells (KO2) were transfected with a vector driving bicistronic expression of GFP and Cdc42 or GFP alone, sorted by FACS, and subjected to gentamicin survival assay with wild-type Listeria as indicated. KO2 cells were statistically compared to C1 cells (*), and to KO2 cells reexpressing Cdc42 (#). In addition, C1 and Cdc42-expressing KO2 were confirmed not to be statistically different (P = 0.76). (C) Activation of Cdc42 in control fibroblasts (C1) by brief treatment (+) (5 min) of starved cells with HGF (20 ng/ml) and InlB (50 ng/ml) as indicated.

FIG. 7.

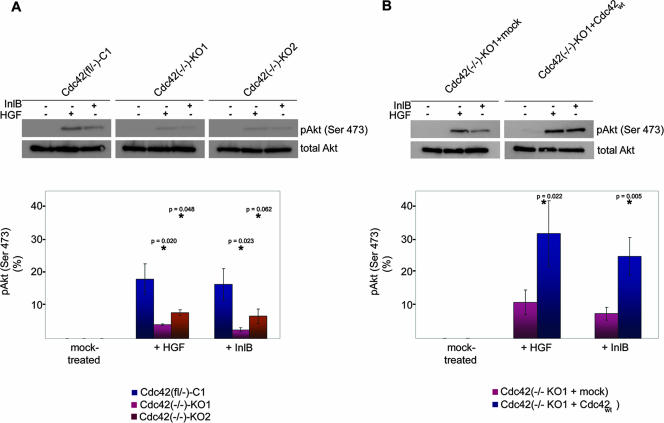

Cdc42 deficiency reduces PI3-kinase activation upon HGF or InlB treatment. (A) Extracts from control [Cdc42(fl/−)-C1] (C1) or Cdc42-deficient cell lines [Cdc42(−/−)-KO1 and -KO2] (KO1 and KO2) mock treated (−) or treated with HGF (20 ng/ml) or InlB (50 ng/ml) (+) were assessed for Akt phosphorylation on serine 473. The top panels show representative blots, and the graphs at the bottom show averaged levels of phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) (as a percentage of total Akt). Growth factor-treated KO1 or KO2 cells were statistically compared to C1 cells (*). (B) As in panel A except that Cdc42-deficient cells (KO1) stably transduced with wild-type Cdc42 or mock plasmid as control were used. Cdc42wt- and mock-transduced cells were statistically compared as indicated (*). Akt phosphorylation following treatment with c-Met ligands was impaired in Cdc42-deficient cells (A) and rescued by Cdc42 reexpression (B). Averaged phospho-Akt (pAkt) levels (bottom graphs) are means plus standard errors of means (error bars) for at least three independent experiments.

Cdc42 signaling through Rac but not N-WASP is required for efficient c-Met-mediated membrane ruffling and Listeria invasion.

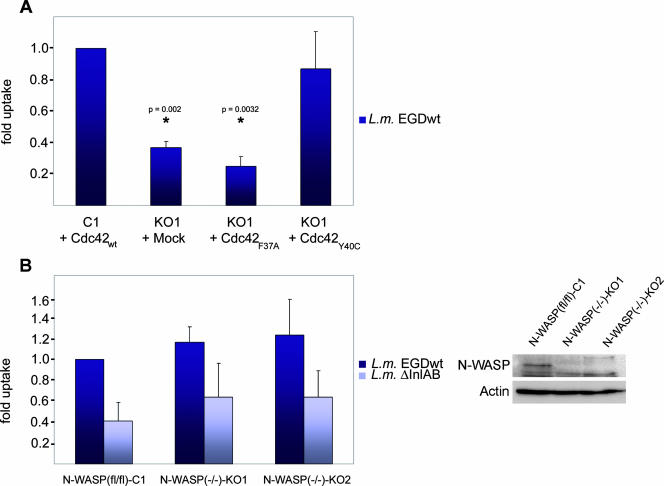

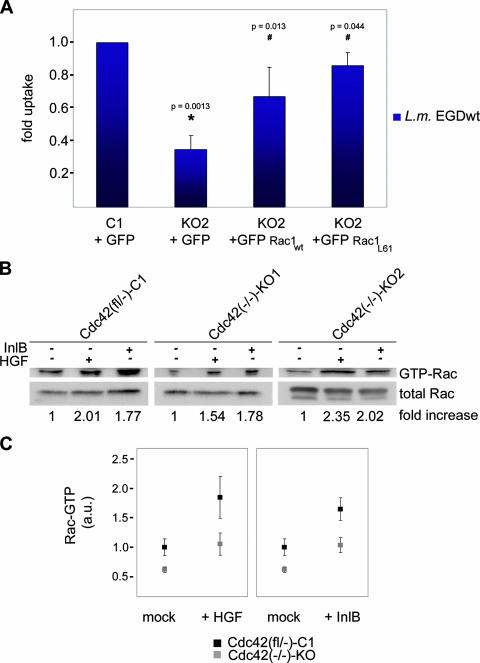

To obtain more insight into the pathway driving Cdc42-mediated cellular responses downstream of c-Met activation, e.g., InlB-mediated Listeria invasion, different effector binding mutants of Cdc42 were stably transduced into Cdc42 null cells. We primarily focused on two point mutants, Y40C and F37A, bearing single amino acid substitutions in the effector loop of Cdc42, reported to block interaction with effectors harboring a CRIB motif, like group I p21-activated kinases (e.g., PAK1) or WASP family proteins, and to abrogate Cdc42 signaling to Rac activation, respectively (27). Cdc42Y40C, but not Cdc42F37A reconstituted Listeria invasion in Cdc42 knockout cells (Fig. 2A), indicating that Cdc42 functions in Listeria engulfment by stimulating Rac activation, rather than by directly controlling actin polymerization through CRIB-containing Cdc42 effectors, such as N-WASP. However, since other investigators had previously raised doubts on the abrogation of N-WASP binding to Cdc42Y40C (32), we sought to confirm by other means that a direct Cdc42-N-WASP pathway does not regulate Cdc42-dependent Listeria invasion. To do that, we examined Listeria engulfment by control [N-WASP(fl/fl)-C1] and two independently generated N-WASP null [N-WASP(−/−)-KO1 and -KO2] cell lines (31), which are also devoid of hematopoietic WASP (2; data not shown). Interestingly, InlB-mediated Listeria invasion was not decreased in the absence of N-WASP/WASP (Fig. 2B), proving that Cdc42-mediated Listeria invasion does not involve N-WASP-driven actin polymerization. Instead, Cdc42 may more likely signal to Rac activation. Thus, we reasoned that if reduced Listeria invasion and InlB signaling following removal of Cdc42 is due to a defective Rac signaling pathway, this defect should be complemented by increasing cellular Rac-GTP levels. Accordingly, transient expression of wild-type Rac1 in Cdc42 knockout fibroblasts partially restored Listeria invasion, and almost full reconstitution was achieved by expression of constitutively active Rac1 (Rac1L61) (Fig. 3A). These data further suggested that Cdc42 null cells might display impaired Rac activation known to accompany Listeria invasion and InlB-mediated signal induction at the plasma membrane (42). To test this directly, we treated control and Cdc42 knockout cell lines with HGF or purified InlB, which is well established to induce cytoskeletal rearrangements similar to HGF (26, 42, 43). As indicated above, serum-starved Cdc42-expressing control cells were morphologically assessed for membrane ruffling after brief treatments (5 min) with various concentrations of both compounds (see also below). Maximal responses were obtained with 20 and 50 ng/ml for HGF and purified InlB, respectively, which were also accompanied by Cdc42 activation (Fig. 1C; see Fig. 6). We then determined relative Rac-GTP levels in the various cell lines (Fig. 3B). Stimulation of c-Met induced a similar increase (around twofold) in Rac-GTP loading in Cdc42 null and control cell lines with respect to mock-treated control cells. However, due to constitutive reduction of Rac-GTP in the absence of Cdc42 as observed previously (12), the absolute increase of Rac-GTP levels upon HGF or InlB treatment was only about half in Cdc42 knockout cells compared to Cdc42-expressing controls (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 2.

The Cdc42/N-WASP pathway is not involved in InlB-mediated Listeria invasion. (A) Cdc42 knockout cells [Cdc42(−/−)-KO1 (KO1)] stably transduced with wild-type Cdc42 (Cdc42wt), different effector binding mutants (Cdc42F37A and Cdc42Y40C), or mock plasmid were examined for Listeria invasion by gentamicin protection assay as indicated. Note the reconstitution of Listeria invasion to wild-type levels with the N-WASP binding-defective Cdc42Y40C mutant, but not with Cdc42F37A, known to be incapable of signaling to Rac activation. Cdc42wt reexpressors were confirmed to be statistically different from mock- and Cdc42F37A-transduced cells as indicated (*), but not from Cdc42Y40C expressors (P = 0.65). L.m. EGDwt, L. monocytogenes EGD wild type. (B) Parental control [N-WASP(fl/fl)-C1] and corresponding N-WASP-defective cell lines [N-WASP(−/−)-KO1 and -KO2] were subjected to gentamicin survival assays with both wild-type L. monocytogenes EGD (L.m. EGDwt) and InlA/B-deficient L. monocytogenes (L.m. ΔInlAB) (left panel). Note the absence of N-WASP expression in KO cell lines (right panel). InlB-specific Listeria invasion is not reduced in the absence of N-WASP (left panel; P = 0.4 and P = 0.56 for KO1 and KO2, respectively).

FIG. 3.

Cdc42 signaling to Rac activation is required for InlB-mediated Listeria invasion. (A) Listeria entry into control [Cdc42(fl/−)-C1] (C1) or Cdc42 knockout cells [Cdc42(−/−)-KO2] (KO2) upon transient bicistronic expression of GFP and wild-type Rac1 (Rac1wt) or constitutively active Rac1 (Rac1L61) or GFP alone as indicated. Expression of both Rac1 variants causes significant increase of Listeria invasion in the absence of Cdc42, close to invasion rates observed in control cells expressing GFP. KO2 cells were statistically compared to C1 cells (*) and to KO2 cells expressing Rac variants as indicated (#). In addition, C1 and Rac1L61-expressing KO2 cells were statistically not different (P = 0.24). L.m. EGDwt, L. monocytogenes EGD wild type. (B) Rac activation in control and Cdc42 knockout cell lines upon InlB or HGF treatment. Blots show representative examples for Rac1 activation compared to mock-treated controls (−). Numbers below lanes give Rac-GTP levels normalized to the respective mock-treated line and expressed as arithmetic means of all measurements (at least five independent experiments). Note the average increase of Rac-GTP of about twofold upon InlB and HGF treatment in all cell lines. (C) Summary of PAK-CRIB pull-down assays shown in panel B. Relative Rac-GTP levels of both knockout cell lines were pooled [Cdc42(−/−)-KO] and normalized to Rac-GTP levels in the mock-treated parental line [Cdc42(fl/−)-C1]. Rac-GTP levels are given in arbitrary units (a.u.). Note compromised Rac-GTP levels of knockout lines (gray) compared to the parental control (black) both with and without HGF or InlB treatment. Data are means ± standard errors of means (error bars). Rac-GTP levels upon treatments with c-Met ligands were confirmed to be higher in Cdc42 control cells than in Cdc42-deficient cells (one-sided two-sample t test; P = 0.042 and 0.0072 for HGF and InlB, respectively).

FIG. 6.

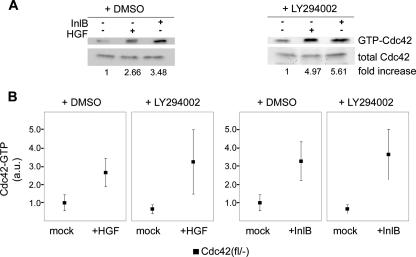

PI3-kinase inhibition does not interfere with InlB- and HGF-induced Cdc42 activation. (A) Quantification of Cdc42 activation by InlB (50 ng/ml) or HGF (20 ng/ml) in the presence (right panels) or absence (left panels) of LY294002 in C1 cells. Data were normalized to the respective Cdc42-GTP levels in the absence of c-Met ligands (−). Numbers below representative blots show arithmetic means for at least six independent experiments. (B) Summary of PAK-CRIB-Cdc42 assays in the presence of vehicle alone (+DMSO) or upon PI3-kinase inhibition (+LY294002). All data are means ± standard errors of means (error bars) and normalized to DMSO-treated cells in the absence of c-Met ligand. Cdc42-GTP levels in growth factor-treated cells were not different in the presence (+LY294002) and absence (+DMSO) of PI3-kinase inhibitor (P = 0.81 and P = 0.91 for HGF and InlB, respectively). Cdc42-GTP levels were given in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Induction of membrane ruffling through c-Met signaling is impaired in the absence of Cdc42.

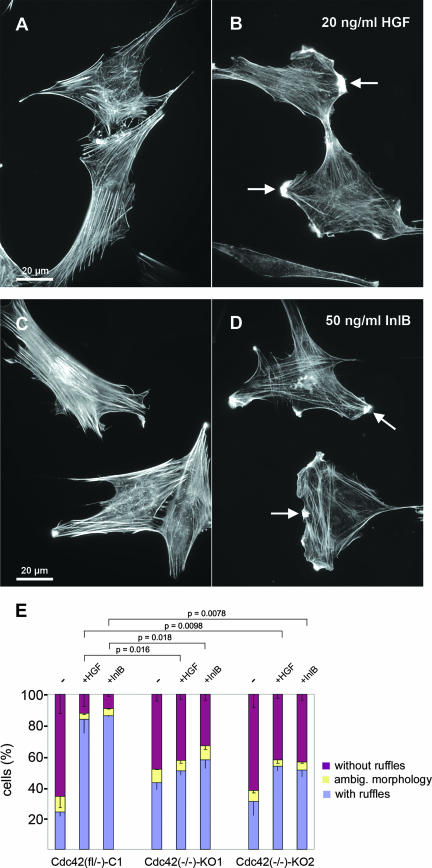

To obtain more insight into the significance and general relevance of Cdc42 function in motogenic c-Met signaling, we assessed whether the observed impairment in Rac activation in Cdc42 null cells affects c-Met-mediated cellular responses. Scattering of epithelial cells is initiated by the formation of prominent plasma membrane protrusions, frequently adopting the shape of membrane ruffles, which can also be evoked in fibroblasts and by InlB (26, 42) (see above). Our Cdc42-expressing control cells formed membrane ruffles in response to both ligands (Fig. 4A to D), displaying an almost fourfold increase in the percentage of ruffling cells compared to mock-treated controls (Fig. 4E). Importantly, those cells (approximately 20%) forming ruffles in the absence of HGF or InlB were virtually indistinguishable from ruffling cells after growth factor treatment. Thus, HGF/InlB treatments affected the frequency, not the quality, of ruffling displayed (not shown). In contrast, whereas individual cells in both untreated and HGF- or InlB-treated Cdc42-deficient cell populations were still capable of membrane ruffling (Fig. 4E), the frequency of cells displaying these structures was hardly increased after HGF or InlB treatment in cells lacking Cdc42 (Fig. 4E). Thus, we conclude that the induction of membrane ruffling downstream of c-Met, not the ruffling machinery, is severely compromised in both Cdc42 knockout cell lines compared to the parental precursor line (Fig. 4E).

FIG. 4.

HGF- and InlB-induced membrane ruffling is impaired in the absence of Cdc42. (A to D) Architecture of the actin cytoskeleton of Cdc42-expressing control fibroblasts upon brief treatment with HGF or InlB (B and D) or without HGF or InlB (A and C) as indicated. Note the prominent induction of membrane ruffles by both compounds (arrows). (E) Quantification of HGF- and InlB-induced membrane ruffling in control and Cdc42-deficient cell lines. Individual cells were classified according to the categories: with ruffles, without ruffles, or with ambiguous (ambig.) morphology. Note the poor increase in the number of cells with ruffles upon HGF or InlB treatment in the absence of Cdc42 [Cdc42(−/−)-KO1 and -KO2] compared to the control line [Cdc42(fl/−)-C1]. Data are means ± standard errors of means (error bars) (n ≥ 300 cells for each experimental condition and cell line). Data sets were statistically compared by one-sided two-sample t tests as indicated.

Relative roles of Cdc42 and PI3-kinase signaling downstream of c-Met.

Rac activation induced by InlB binding to c-Met has been assumed to be largely mediated by class I PI3-kinases, which generate phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate needed to recruit and activate guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for Rho family GTPases (36, 42). Consistently, InlB-mediated Listeria invasion was shown to be significantly impaired by pharmacological inhibition of PI3-kinase (25). This and our results on the critical role of Cdc42 in Rac activation prompted us to ask whether PI3-kinase and Cdc42 act in common or distinct pathways during InlB-mediated Listeria entry. We employed two widely used competitive inhibitors of PI3-kinase, wortmannin and LY294002, focusing primarily on the latter due to its greater stability (53). Dose-response curves of inhibition of InlB-mediated Listeria invasion were obtained using Cdc42-expressing control fibroblasts (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Similar to previous observations in other cell types (25), concentrations of LY294002 between 1 and 5 μM caused a rapid and linear reduction of Listeria invasion. The minimal concentration to reach maximal inhibition was 10 μM (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material), which was then used in subsequent experiments. To confirm that 10 μM LY294002 indeed abolished PI3-kinase activation upon induction of c-Met signaling in our cell types, the phosphorylation (serine 473) of endogenous Akt/protein kinase B (10) before and after HGF or InlB treatment was analyzed. As expected, Akt phosphorylation was entirely abolished upon LY294002 treatments in all cell types and experimental conditions (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material).

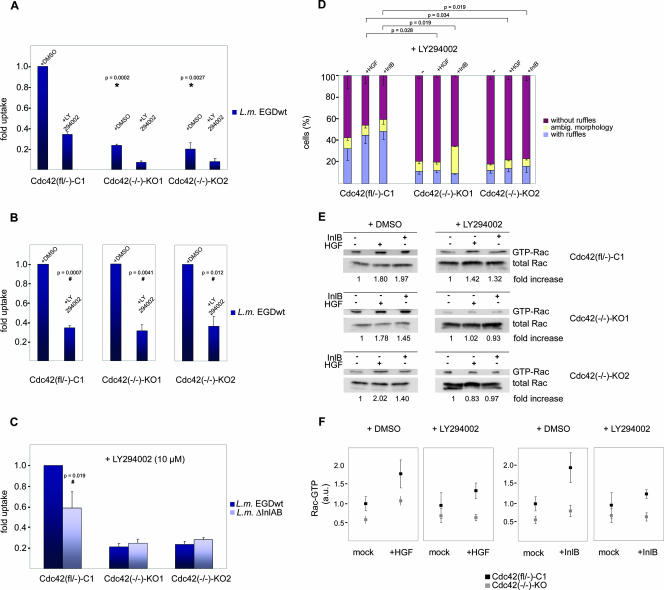

Interestingly, PI3-kinase inhibition strongly reduced Listeria entry in both Cdc42-expressing parental and Cdc42 knockout cells (Fig. 5A). More specifically, although the absence of Cdc42 already caused a marked decrease of Listeria invasion in the presence of vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) as expected (Fig. 5A), these entry rates were as sensitive to PI3-kinase inhibition as the ones observed in Cdc42-expressing cells, which is illustrated best when entry rates are normalized to 1 (100%) for each mock-treated cell line individually (Fig. 5B). Thus, PI3-kinase inhibition affects Listeria invasion irrespective of Cdc42 expression. Moreover, wortmannin (100 nM), which is known to abrogate PI3-kinase activity in fibroblast cell lines generated and immortalized in a manner comparable to the ones used here (8), also reduced Listeria invasion equally effective in the presence and absence of Cdc42 (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Together, this body of evidence shows that the enzymatic activity of PI3-kinase is not positioned upstream of Cdc42 in c-Met-induced Listeria invasion. Furthermore, these data suggest that the remaining Listeria entry observed in Cdc42-deficient cells is sensitive to PI3-kinase inhibition and that the PI3-kinase activity-independent entry in Cdc42-expressing cells (Fig. 5A) requires Cdc42. This conclusion is corroborated by comparison of entry of wild-type and InlA/B-deficient strains into LY294002-treated cell lines, which confirmed a complete abolishment of InlB-specific invasion in the absence of both Cdc42 and PI3-kinase activity and the existence of InlB-specific and Cdc42-dependent invasion in the presence of this GTPase (Fig. 5C). Further, these data revealed the absence of additional signaling pathways driving InlB-mediated Listeria invasion in PI3-kinase-inhibited Cdc42-deficient cells.

FIG. 5.

PI3-kinase inhibition interferes with motogenic c-Met-signaling both in the presence and absence of Cdc42. (A) Invasion of wild-type Listeria monocytogenes EGD (L.m. EGDwt) into control [Cdc42(fl/−)-C1] (C1) and knockout cell lines [Cdc42(−/−)-KO1 and -KO2] (KO1 and KO2) treated with vehicle (+DMSO) or LY294002 as indicated. Note statistically significant reduction of bacterial invasion (*) in KO compared to C1 cells in the presence of vehicle (DMSO). (B) Data as in panel A normalized to the entry rates with vehicle for each cell line individually. Reduction of bacterial entry was statistically confirmed to be significant for each cell line (#). (C) Control and Cdc42-deficient cells treated with LY294002 and infected with wild-type and ΔInlA/B Listeria monocytogenes (L.m.) as indicated. Note that InlB-dependent invasion is abolished in both Cdc42-deficient lines in the presence of LY294002 (invasion of wild-type and ΔInlA/B Listeria is equal), whereas a good fraction of Cdc42-dependent entry into control cells (C1) under these conditions is InlB-dependent (#, comparison of entry of wild-type L. monocytogenes EGD versus L. monocytogenes ΔInlAB; one-sided one-sample t test). Loss of Cdc42 also affects efficiency of InlB-independent (nonspecific) entry. Data are means plus standard errors of means (error bars). (D) Induction of HGF- or InlB-induced membrane ruffling in the presence of LY294002. In Cdc42-deficient cell lines (KO1 and KO2), the induction of membrane ruffling is completely suppressed under these conditions, whereas the Cdc42-expressing control line (C1) still displays a moderate increase of the percentage of cells with ruffles. Data sets were statistically compared by one-sided two-sample t tests as indicated. −, no treatment; ambig., ambiguous. (E) Rac activation assays in the presence (+) or absence of LY294002 in all cell lines as indicated and normalized to the respective Rac-GTP levels in the absence (−) of InlB or HGF. Numbers below representative blots give arithmetic means for at least five independent experiments. Note the absence of Rac activation by HGF or InlB in Cdc42-deficient cell lines (KO1 and KO2) treated with LY294002 as opposed to the moderate increase of Rac-GTP levels under these conditions in the control cell line (C1). (F) Summary of PAK-CRIB assays performed with all lines in the presence of vehicle alone (+DMSO) or upon PI3-kinase inhibition (+LY294002). All data are means ± standard errors of means (error bars) and normalized to DMSO-treated Cdc42-expressing controls (C1) in the absence of c-Met ligand. Data from Cdc42-deficient cell lines were pooled and displayed as Cdc42(−/−)-KO (gray) and compared to Cdc42-expressing parental precursor cell line (black). In the presence of LY294002, Rac-GTP levels upon growth factor challenge were statistically confirmed to be larger in C1 cells than in Cdc42 KO cells (P = 0.0049 and P = 0.0009 for HGF and InlB, respectively). Rac-GTP levels are given in arbitrary units (a.u.).

Next, we asked whether the relative contributions of Cdc42 and PI3-kinase to Listeria entry are specific for the InlB pathway or can be extended to HGF-induced membrane ruffling. To do that, the ruffle-forming capability in response to HGF or soluble InlB as a control was examined in Cdc42 control or knockout cells in the presence or absence of LY294002. PI3-kinase inhibition totally abolished HGF- and InlB-induced membrane ruffling in the absence of Cdc42, but not in Cdc42-expressing cells (Fig. 5D). Moreover, similar to the observations with Listeria invasion, the induction of membrane ruffling by brief HGF or InlB treatment was quantitatively comparable in mock-treated Cdc42 knockout cells (Fig. 4E) and PI3-kinase inhibitor-treated Cdc42-expressing controls (Fig. 5D). These data demonstrate the collective requirement of Cdc42 and PI3-kinase activities for the induction of membrane ruffling downstream of c-Met signaling, although neither one of the two components is absolutely essential.

To test whether these phenotypic observations correlate with changes in Rac activation, we examined Rac-GTP levels in control and Cdc42 knockout cell lines treated either with vehicle or LY294002. The relative increase of Rac-GTP levels stimulated by both HGF and InlB was reduced but not abrogated upon PI3-kinase inhibition in Cdc42-expressing cells, whereas LY294002 completely abolished Rac GTP-loading in the absence of Cdc42 (Fig. 5E and F). As opposed to Rac, Cdc42 activation upon HGF or InlB treatment of control fibroblasts was at least as robust in the presence of PI3-kinase inhibitor as in its absence (Fig. 6), providing biochemical proof that Cdc42 activation downstream of c-Met stimulation is PI3-kinase activity independent in our system. These latter results are consistent with the observation that HGF-induced activation of Cdc42 in MDCK epithelial cells is also insensitive to PI3-kinase inhibition (39).

Cdc42 deficiency reduces PI3-kinase signaling.

The data presented so far clearly revealed both Cdc42- and PI3-kinase-dependent pathways of motogenic c-Met signaling, which were separable from each other, at least in part. However, since Cdc42 was previously reported to be able to bind to and activate PI3-kinase by direct interaction with its regulatory subunit (p85) (51, 59), we examined PI3-kinase activation by HGF or InlB treatment in the presence and absence of Cdc42. Interestingly, Akt phosphorylation (on serine 473) following HGF or InlB addition was significantly reduced in both Cdc42-deficient cell lines compared to parental Cdc42-expressing controls (Fig. 7A). Along the same line, Cdc42 null cells stably reexpressing Cdc42wt showed an approximately threefold increase in phospho-Akt levels compared to the same line transduced with mock vector (Fig. 7B). These data strongly suggest that PI3-kinase activation downstream of c-Met engagement is driven in part by Cdc42.

Collectively, our results uncover for the first time that, following c-Met activation, PI3-kinase enzymatic activity does not lie upstream of Cdc42, whereas Cdc42 signaling to Rac activation partly involves PI3-kinase function (see also Fig. 9).

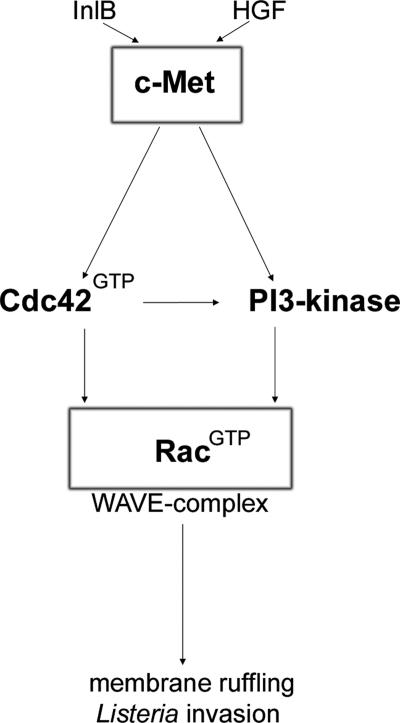

FIG. 9.

Schematic summary of the data presented in this study: Interaction of the receptor tyrosine kinase c-Met with its ligand (HGF or InlB) stimulates Cdc42- and PI3-kinase-dependent signaling cascades, which converge on Rac activation (RacGTP). Interestingly, PI3-kinase-dependent Rac activation can occur both in parallel to and downstream of Cdc42. GTP-loaded Rac in turn drives WAVE complex-dependent rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton, essential for membrane ruffling and Listeria invasion.

The Rac/WAVE complex pathway is essential for Listeria entry.

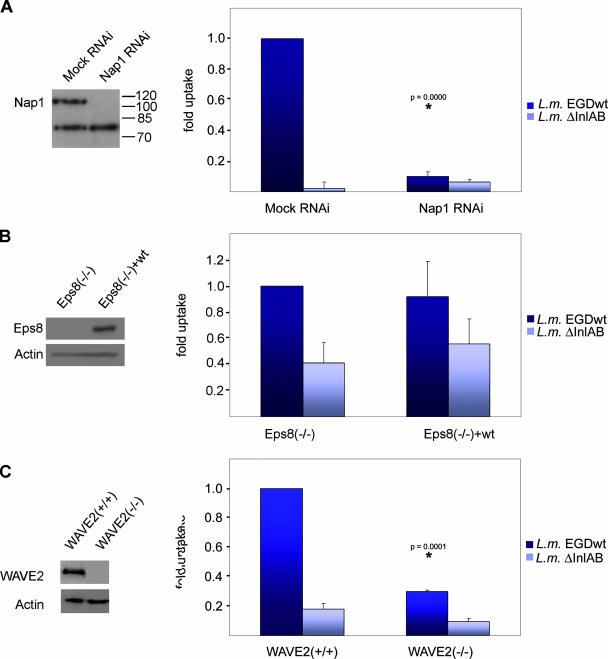

To directly test whether actin polymerization downstream of Rac is essential for Listeria invasion, we first employed fibroblast cell lines stably suppressed for Nap1, an essential constituent of a pentameric protein assembly called WAVE complex (46, 49). The ubiquitously expressed version of this complex comprises Sra-1/PIR121, Nap1, Abi-1 (Abl-interacting protein 1), HSPC300, and WAVE2 (19), and links Rac1 activation to Arp2/3-mediated lamellipodium protrusion and membrane ruffling (24, 46). Consistently, Nap1 knockdown fibroblasts fail to form lamellipodia and membrane ruffles in response to EGF or platelet-derived growth factor stimulation and to microinjection of constitutively active Rac1 (46). In addition, Nap1 knockdown and control fibroblasts are of human origin (VA-13), and express c-Met but not E-cadherin as judged by Western blotting and Affymetrix gene array analyses (not shown), thus allowing analysis of Listeria entry through the InlB/c-Met pathway in analogy to murine cell lines. Interestingly, entry of wild-type Listeria was nearly abolished in Nap1 knockdown cells compared to mock small interfering RNA-treated controls (Fig. 8A), similar to previous observations with RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of WAVE isoforms and Abi-1 (4). These data already indicated that Rac drives Listeria invasion through WAVE and Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin polymerization. However, Nap1 knockdown also leads to down-regulation of expression of other WAVE complex constituents, including Abi-1 (23, 45), which is a multifunctional adaptor protein regulating the actin cytoskeleton by assembling into several distinct protein complexes (14). In addition to associating with WAVE complex members, Abi-1 interacts with Eps8 and Sos-1 to form a Rac-specific GEF complex (13) and binds and activates N-WASP both in vitro and in vivo (23). Since N-WASP knockout cells displayed no defects in Listeria invasion (Fig. 2B), indirect down-regulation of N-WASP-mediated actin assembly due to reduced Abi-1 expression does not account for abolished entry rates in Nap1 knockdown cells. The Eps8/Abi-1/Sos-1 complex mediates Rac activation and membrane ruffling downstream of receptor tyrosine kinases, such as the platelet-derived growth factor receptor and Ras/PI3-kinase (13) and is disrupted in fibroblasts genetically deficient for Eps8 (41). Whether this complex also functions in Rac activation downstream of c-Met signaling is unknown. To rule out indirect interference upon Nap1 knockdown with Rac activation by the Eps8/Abi-1/Sos-1 complex, Listeria invasion was examined in Eps8 knockout fibroblasts compared to the same cells stably reexpressing Eps8. However, the absence of Eps8 expression had no effect on InlB-mediated Listeria invasion (Fig. 8B), excluding a role for the Eps8/Abi-1/Sos-1 complex in driving Rac activation downstream of c-Met.

FIG. 8.

WAVE complex engagement downstream of Rac is essential for InlB-mediated Listeria invasion. (A) Listeria invasion assays using gentamicin survival assay into mock and Nap1 small interfering RNA-treated VA-13 fibroblasts. (Left) Western blotting reveals virtual absence of Nap1 in stable Nap1 RNAi cells. The cross-reaction of the antibody was used as loading control. (Right) Results of gentamicin protection assay with wild-type Listeria monocytogenes EGD (L.m. EGDwt) and isogenic mutant lacking InlA and InlB (L. monocytogenes ΔInlAB [L.m. ΔInlAB]). InlB-specific Listeria invasion was virtually abolished in Nap1 knockdown cells compared to mock RNAi-treated controls (*, P = 0.0000). (B) Eps8-deficient fibroblasts [Eps8(−/−)] and the same cells reexpressing Eps8 as a control (left panel) were subjected to gentamicin protection assay with wild-type Listeria (L.m. EGDwt) and InlA/B-deficient strain (L.m. ΔInlAB) (right panel). Efficiency of InlB-mediated Listeria invasion is independent of Eps8 expression (P = 0.78). (C) Wild-type fibroblasts [WAVE2(+/+)] and fibroblasts lacking the ubiquitous WAVE2 isoform (left panel) [WAVE2(−/−)] were subjected to gentamicin protection assay with wild-type Listeria (L.m. EGDwt) and InlA/B-deficient strain (L.m. ΔInlAB) as indicated (right panel). InlB-dependent Listeria entry was strongly reduced in the absence of WAVE2 (*, P = 0.0001). Data are means plus standard errors of means (error bars) from at least three independent experiments.

Mammals express three WAVE (also called Scar) proteins, the ubiquitous WAVE2 and two largely neuronal isoforms, WAVE1 and WAVE3 (48), all shown to associate with the aforementioned WAVE complex components (15, 19, 47). Thus, Nap1 knockdown is expected to interfere with proper positioning at the leading edge of all expressed WAVE isoforms. Nevertheless, to obtain independent confirmation of WAVE complex function in Rac-mediated actin reorganization downstream of c-Met, Listeria entry rates were measured in fibroblast cells genetically deficient for WAVE2 (57). As expected, these cells displayed a strong reduction in entry rates compared to their respective controls (Fig. 8C). Together, these data collectively suggest a specific and essential function for the WAVE complex in driving Rac-mediated motogenic c-Met signaling.

DISCUSSION

Reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, e.g., downstream of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling, has been receiving significant attention over the years, with a plethora of key players implicated in this process (14, 37). However, the relevance of individual key players relative to each other within the same pathway and relative to other pathways has remained largely enigmatic. The systematic analysis of these pathways has been hampered by the lack of specificity of frequently employed tools, as highlighted most recently by the limitations recognized for employing the expression of dominant-negative Rho-GTPase variants (54). Thus, the specific removal of components of these signaling pathways by forward and/or reverse genetics such as RNA interference will undoubtedly continue to gain importance in the dissection of these signaling pathways. We employed fibroblastoid cell lines deficient for the prominent Rho family GTPase Cdc42, which we could previously demonstrate to be devoid of any clear-cut phenotypes in both lamellipodium and filopodium protrusion as well as directed cell migration (12). More recently, these surprising results were proposed to be explained by cell transformation, since alternatively generated primary fibroblasts were reported to be more severely affected by the removal of Cdc42 (54, 58). However, although the reasons for this discrepancy remain unclear, transformation cannot account for it, since we could show that the migratory performance of nontransformed endothelial cells is also insensitive to Cdc42 deletion (12). In addition, Cdc42-deficient fibroblast cell lines did indeed show phenotypes, e.g., reduced constitutive Rac-GTP levels (12). Interestingly enough, lowered Rac-GTP levels did not significantly impact on these cells' migratory performance or lamellipodium formation on fibronectin, which may, at least in part, be explained by Cdc42-independent Rac activation through integrins (9).

To learn more about specific roles of Cdc42 in signaling pathways controlling actin reorganization, we have focused here on actin assembly processes induced downstream of engagement of the prominent receptor tyrosine kinase c-Met, which is essential for both HGF-induced membrane ruffling, scattering, and InlB-mediated invasion of Listeria (3, 5). This pathway turned out to be highly sensitive to Cdc42 removal (Fig. 1 and 4). Moreover, reduced Rac-GTP loading downstream of Cdc42 was causative for the observed defects in Listeria entry and in HGF- or InlB-induced membrane ruffling (Fig. 2 and 3). Somewhat surprisingly, Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin filament nucleation by the Cdc42 effector N-WASP was not involved in Cdc42-dependent Listeria entry (Fig. 2). Consistently, N-WASP was also not required for membrane ruffling and lamellipodium formation induced by serum (44) or by microinjection of constitutively active Cdc42 (our unpublished results). Importantly, our quantifications of membrane ruffling in control and Cdc42-deficient cells revealed that Cdc42 is not an essential component of the membrane ruffling machinery downstream of c-Met signaling, as expected (12). Instead, it is very important for induction of these structures through c-Met and perhaps other receptor tyrosine kinases. Hence, our results suggest a specific function of this GTPase in signal propagation rather than output evoked by activation of distinct receptor tyrosine kinases. This conclusion is corroborated by defective induction of ruffles by EGF in the absence of Cdc42 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

We also analyzed the relative function of Cdc42 and PI3-kinase in signal propagation to actin reorganization downstream of c-Met activation. Interestingly, we found both Cdc42- and PI3-kinase-dependent contributions to this signaling pathway, which were independent of the respective other component (Fig. 5 and 9). However, whereas Cdc42 activation was entirely independent of PI3-kinase activity (Fig. 6), Cdc42 could also signal, at least in part, to PI3-kinase activation downstream of c-Met engagement (Fig. 7). This was somewhat surprising, since PI3-kinase activation by serum was independent of Cdc42 (12). Nevertheless, phospho-Akt levels after HGF or InlB treatment were significantly reduced in Cdc42 knockout cell lines and could be complemented by Cdc42 reexpression (Fig. 7), suggesting direct PI3-kinase activation by Cdc42, as previously reported (51, 59). In addition though, PI3-kinase was also shown to bind to Rac (51), which could activate the former both in vitro (6) and in vivo (20). Hence, Cdc42 might drive PI3-kinase activation indirectly through Rac1. However, it was recently reported that PI3-kinase activation by InlB was not affected by Rac1 inhibition through cholesterol depletion, indicating the absence of a positive-feedback loop from Rac to PI3-kinase activation downstream of c-Met signaling (42). Thus, we conclude that Cdc42-mediated PI3-kinase activation downstream of c-Met is not driven by Rac. Instead, both Cdc42 and PI3-kinase act upstream of Rac-mediated actin assembly in both separable and inseparable pathways, since full PI3-kinase activation partly depends on the presence of Cdc42 (Fig. 9). Cdc42 and PI3-kinase signaling are collectively but not individually essential for c-Met-mediated actin reorganization, since simultaneous loss of PI3-kinase and Cdc42 function is required to abolish Listeria entry, HGF/InlB-induced Rac activation, and membrane ruffling (Fig. 5). These results are also consistent with the recently reported nonessential functions of PI3-kinase signaling pathways in neutrophil and Dictyostelium chemotaxis (1, 18, 33).

Finally, we tested for the relevance of the Rac effector WAVE complex in c-Met-induced actin reorganization (Fig. 8). Partly consistent with previous observations (4), WAVE complex-mediated actin reorganization as tested for by Nap1 knockdown was absolutely essential not only for Rac-induced lamellipodium protrusion and membrane ruffling as previously observed (24, 46) but also for InlB-mediated Listeria entry (Fig. 8A). Thus, we conclude that the WAVE complex is likely required for actin assembly downstream of Rac in c-Met signaling (Fig. 9) for several reasons. First, the WAVE complex has turned out to be a key effector of Rac-induced actin polymerization events in various systems (49). Second, genetic removal of WAVE2 strongly interfered with Listeria invasion (Fig. 8C), though it did not abolish it, most presumably due to low amounts of WAVE1 expression (4, 50). Third, Nap1 knockdown VA-13 fibroblasts, which were deficient in Listeria invasion (Fig. 8A), are competent for Cdc42-induced filopodium protrusion (45), which is also driven by actin polymerization, arguing in favor of impairment of a specific signaling pathway, rather than a general defect in actin assembly or turnover. Fourth, an indirect abrogation of upstream Rac activation in Nap1 knockdown cells by disruption of a Sos1-dependent Rac-GEF complex, which also contains the WAVE complex constituent Abi-1, could be excluded through the use of Eps8-deficient cells (Fig. 8B). Therefore, although it remains difficult to formally exclude a contribution of individual WAVE complex components in signaling to Rac activation, as suggested recently for the hematopoietic complex constituent and Nap1 orthologue Hem-1 (55), the simplest interpretation of our results is that of an essential function for the WAVE complex in InlB-mediated Listeria entry by linking Rac activation to Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin polymerization.

In conclusion, we have uncovered a so far unrecognized N-WASP-independent contribution of Cdc42 to Rac-mediated actin rearrangements downstream of motogenic signaling evoked by c-Met receptor ligands (Fig. 9). This pathway can be partially separated from PI3-kinase signaling. Moreover, c-Met-induced actin rearrangements are fully inhibited only in the absence of both Cdc42 and PI3-kinase activity. Interestingly, Cdc42 and PI3-kinase signaling pathways do not operate in a simple additive manner concerning the efficiency of induced ruffling or Listeria engulfment, since interference with either pathway strongly impairs these responses. Instead, they appear to individually and together contribute to exceeding threshold levels of Rac-GTP needed for efficient output signaling to occur. The latter requires functional WAVE complex (Fig. 9). Future studies will address the identification of PI3-kinase-dependent and -independent GEF activities driving this signaling pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Brigitte Denker for excellent technical assistance, Lothar Gröbe and Maria Höxter for FACS, Tadaomi Takenawa for kindly providing WAVE2 knockout cells, Gustav Bernroider for help with statistics, and Juergen Wehland for providing Listeria strains and for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 621 to K.R. and SPP1150 to T.E.B.S. and K.R.), Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) (to G.S.), and Human Science Frontier Program (RGP0072/2003-C to G.S.). T.B. was supported by a Georg-Christoph-Lichtenberg fellowship of Lower Saxony.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 August 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrew, N., and R. H. Insall. 2007. Chemotaxis in shallow gradients is mediated independently of PtdIns 3-kinase by biased choices between random protrusions. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benesch, S., S. Lommel, A. Steffen, T. E. Stradal, N. Scaplehorn, M. Way, J. Wehland, and K. Rottner. 2002. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2)-induced vesicle movement depends on N-WASP and involves Nck, WIP, and Grb2. J. Biol. Chem. 277:37771-37776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bierne, H., and P. Cossart. 2002. InlB, a surface protein of Listeria monocytogenes that behaves as an invasin and a growth factor. J. Cell Sci. 115:3357-3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bierne, H., H. Miki, M. Innocenti, G. Scita, F. B. Gertler, T. Takenawa, and P. Cossart. 2005. WASP-related proteins, Abi1 and Ena/VASP are required for Listeria invasion induced by the Met receptor. J. Cell Sci. 118:1537-1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birchmeier, C., W. Birchmeier, E. Gherardi, and G. F. Vande Woude. 2003. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:915-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bokoch, G. M., C. J. Vlahos, Y. Wang, U. G. Knaus, and A. E. Traynor-Kaplan. 1996. Rac GTPase interacts specifically with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Biochem. J. 315:775-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bompard, G., and E. Caron. 2004. Regulation of WASP/WAVE proteins: making a long story short. J. Cell Biol. 166:957-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brachmann, S. M., C. M. Yballe, M. Innocenti, J. A. Deane, D. A. Fruman, S. M. Thomas, and L. C. Cantley. 2005. Role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulatory isoforms in development and actin rearrangement. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:2593-2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brakebusch, C., and R. Fassler. 2003. The integrin-actin connection, an eternal love affair. EMBO J. 22:2324-2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brazil, D. P., Z. Z. Yang, and B. A. Hemmings. 2004. Advances in protein kinase B signalling: AKTion on multiple fronts. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:233-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burridge, K., and K. Wennerberg. 2004. Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell 116:167-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czuchra, A., X. Wu, H. Meyer, J. van Hengel, T. Schroeder, R. Geffers, K. Rottner, and C. Brakebusch. 2005. Cdc42 is not essential for filopodium formation, directed migration, cell polarization, and mitosis in fibroblastoid cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:4473-4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Fiore, P. P., and G. Scita. 2002. Eps8 in the midst of GTPases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34:1178-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Disanza, A., A. Steffen, M. Hertzog, E. Frittoli, K. Rottner, and G. Scita. 2005. Actin polymerization machinery: the finish line of signaling networks, the starting point of cellular movement. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62:955-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eden, S., R. Rohatgi, A. V. Podtelejnikov, M. Mann, and M. W. Kirschner. 2002. Mechanism of regulation of WAVE1-induced actin nucleation by Rac1 and Nck. Nature 418:790-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsinghorst, E. A. 1994. Measurement of invasion by gentamicin resistance. Methods Enzymol. 236:405-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faix, J., and K. Rottner. 2006. The making of filopodia. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18:18-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson, G. J., L. Milne, S. Kulkarni, T. Sasaki, S. Walker, S. Andrews, T. Crabbe, P. Finan, G. Jones, S. Jackson, M. Camps, C. Rommel, M. Wymann, E. Hirsch, P. Hawkins, and L. Stephens. 2007. PI(3)Kgamma has an important context-dependent role in neutrophil chemokinesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:86-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gautreau, A., H. Y. Ho, J. Li, H. Steen, S. P. Gygi, and M. W. Kirschner. 2004. Purification and architecture of the ubiquitous Wave complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4379-4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genot, E. M., C. Arrieumerlou, G. Ku, B. M. Burgering, A. Weiss, and I. M. Kramer. 2000. The T-cell receptor regulates Akt (protein kinase B) via a pathway involving Rac1 and phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:5469-5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall, A. 1998. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science 279:509-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamon, M., H. Bierne, and P. Cossart. 2006. Listeria monocytogenes: a multifaceted model. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:423-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Innocenti, M., S. Gerboth, K. Rottner, F. P. Lai, M. Hertzog, T. E. Stradal, E. Frittoli, D. Didry, S. Polo, A. Disanza, S. Benesch, P. P. Di Fiore, M. F. Carlier, and G. Scita. 2005. Abi1 regulates the activity of N-WASP and WAVE in distinct actin-based processes. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:969-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Innocenti, M., A. Zucconi, A. Disanza, E. Frittoli, L. B. Areces, A. Steffen, T. E. Stradal, P. P. Di Fiore, M. F. Carlier, and G. Scita. 2004. Abi1 is essential for the formation and activation of a WAVE2 signalling complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:319-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ireton, K., B. Payrastre, H. Chap, W. Ogawa, H. Sakaue, M. Kasuga, and P. Cossart. 1996. A role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in bacterial invasion. Science 274:780-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ireton, K., B. Payrastre, and P. Cossart. 1999. The Listeria monocytogenes protein InlB is an agonist of mammalian phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17025-17032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamarche, N., N. Tapon, L. Stowers, P. D. Burbelo, P. Aspenstrom, T. Bridges, J. Chant, and A. Hall. 1996. Rac and Cdc42 induce actin polymerization and G1 cell cycle progression independently of p65PAK and the JNK/SAPK MAP kinase cascade. Cell 87:519-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lecuit, M., S. Dramsi, C. Gottardi, M. Fedor-Chaiken, B. Gumbiner, and P. Cossart. 1999. A single amino acid in E-cadherin responsible for host specificity towards the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. EMBO J. 18:3956-3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, N., G. S. Xiang, H. Dokainish, K. Ireton, and L. A. Elferink. 2005. The Listeria protein internalin B mimics hepatocyte growth factor-induced receptor trafficking. Traffic 6:459-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lommel, S., S. Benesch, M. Rohde, J. Wehland, and K. Rottner. 2004. Enterohaemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli use different mechanisms for actin pedestal formation that converge on N-WASP. Cell. Microbiol. 6:243-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lommel, S., S. Benesch, K. Rottner, T. Franz, J. Wehland, and R. Kuhn. 2001. Actin pedestal formation by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and intracellular motility of Shigella flexneri are abolished in N-WASP-defective cells. EMBO Rep. 2:850-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miki, H., T. Sasaki, Y. Takai, and T. Takenawa. 1998. Induction of filopodium formation by a WASP-related actin-depolymerizing protein N-WASP. Nature 391:93-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishio, M., K. Watanabe, J. Sasaki, C. Taya, S. Takasuga, R. Iizuka, T. Balla, M. Yamazaki, H. Watanabe, R. Itoh, S. Kuroda, Y. Horie, I. Forster, T. W. Mak, H. Yonekawa, J. M. Penninger, Y. Kanaho, A. Suzuki, and T. Sasaki. 2007. Control of cell polarity and motility by the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase SHIP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:36-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nobes, C. D., and A. Hall. 1995. Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell 81:53-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parida, S. K., E. Domann, M. Rohde, S. Muller, A. Darji, T. Hain, J. Wehland, and T. Chakraborty. 1998. Internalin B is essential for adhesion and mediates the invasion of Listeria monocytogenes into human endothelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 28:81-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pizarro-Cerda, J., and P. Cossart. 2006. Subversion of cellular functions by Listeria monocytogenes. J. Pathol. 208:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raftopoulou, M., and A. Hall. 2004. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev. Biol. 265:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rottner, K., T. E. Stradal, and J. Wehland. 2005. Bacteria-host-cell interactions at the plasma membrane: stories on actin cytoskeleton subversion. Dev. Cell 9:3-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Royal, I., N. Lamarche-Vane, L. Lamorte, K. Kaibuchi, and M. Park. 2000. Activation of cdc42, rac, PAK, and rho-kinase in response to hepatocyte growth factor differentially regulates epithelial cell colony spreading and dissociation. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:1709-1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schubert, W. D., C. Urbanke, T. Ziehm, V. Beier, M. P. Machner, E. Domann, J. Wehland, T. Chakraborty, and D. W. Heinz. 2002. Structure of internalin, a major invasion protein of Listeria monocytogenes, in complex with its human receptor E-cadherin. Cell 111:825-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scita, G., J. Nordstrom, R. Carbone, P. Tenca, G. Giardina, S. Gutkind, M. Bjarnegard, C. Betsholtz, and P. P. Di Fiore. 1999. EPS8 and E3B1 transduce signals from Ras to Rac. Nature 401:290-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seveau, S., T. N. Tham, B. Payrastre, A. D. Hoppe, J. A. Swanson, and P. Cossart. 2007. A FRET analysis to unravel the role of cholesterol in Rac1 and PI 3-kinase activation in the InlB/Met signalling pathway. Cell. Microbiol. 9:790-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen, Y., M. Naujokas, M. Park, and K. Ireton. 2000. InIB-dependent internalization of Listeria is mediated by the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. Cell 103:501-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snapper, S. B., F. Takeshima, I. Anton, C. H. Liu, S. M. Thomas, D. Nguyen, D. Dudley, H. Fraser, D. Purich, M. Lopez-Ilasaca, C. Klein, L. Davidson, R. Bronson, R. C. Mulligan, F. Southwick, R. Geha, M. B. Goldberg, F. S. Rosen, J. H. Hartwig, and F. W. Alt. 2001. N-WASP deficiency reveals distinct pathways for cell surface projections and microbial actin-based motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:897-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steffen, A., J. Faix, G. P. Resch, J. Linkner, J. Wehland, J. V. Small, K. Rottner, and T. E. Stradal. 2006. Filopodia formation in the absence of functional WAVE- and Arp2/3-complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:2581-2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steffen, A., K. Rottner, J. Ehinger, M. Innocenti, G. Scita, J. Wehland, and T. E. Stradal. 2004. Sra-1 and Nap1 link Rac to actin assembly driving lamellipodia formation. EMBO J. 23:749-759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stovold, C. F., T. H. Millard, and L. M. Machesky. 2005. Inclusion of Scar/WAVE3 in a similar complex to Scar/WAVE1 and 2. BMC Cell Biol. 6:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stradal, T. E., K. Rottner, A. Disanza, S. Confalonieri, M. Innocenti, and G. Scita. 2004. Regulation of actin dynamics by WASP and WAVE family proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 14:303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stradal, T. E., and G. Scita. 2006. Protein complexes regulating Arp2/3-mediated actin assembly. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18:4-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suetsugu, S., D. Yamazaki, S. Kurisu, and T. Takenawa. 2003. Differential roles of WAVE1 and WAVE2 in dorsal and peripheral ruffle formation for fibroblast cell migration. Dev. Cell 5:595-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tolias, K. F., L. C. Cantley, and C. L. Carpenter. 1995. Rho family GTPases bind to phosphoinositide kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17656-17659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veiga, E., and P. Cossart. 2005. Listeria hijacks the clathrin-dependent endocytic machinery to invade mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:894-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker, E. H., M. E. Pacold, O. Perisic, L. Stephens, P. T. Hawkins, M. P. Wymann, and R. L. Williams. 2000. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition by wortmannin, LY294002, quercetin, myricetin, and staurosporine. Mol. Cell 6:909-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang, L., and Y. Zheng. 2007. Cell type-specific functions of Rho GTPases revealed by gene targeting in mice. Trends Cell Biol. 17:58-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weiner, O. D., M. C. Rentel, A. Ott, G. E. Brown, M. Jedrychowski, M. B. Yaffe, S. P. Gygi, L. C. Cantley, H. R. Bourne, and M. W. Kirschner. 2006. Hem-1 complexes are essential for Rac activation, actin polymerization, and myosin regulation during neutrophil chemotaxis. PLoS Biol. 4:e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wells, C. M., T. Ahmed, J. R. Masters, and G. E. Jones. 2005. Rho family GTPases are activated during HGF-stimulated prostate cancer-cell scattering. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 62:180-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamazaki, D., S. Suetsugu, H. Miki, Y. Kataoka, S. Nishikawa, T. Fujiwara, N. Yoshida, and T. Takenawa. 2003. WAVE2 is required for directed cell migration and cardiovascular development. Nature 424:452-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang, L., L. Wang, and Y. Zheng. 2006. Gene targeting of Cdc42 and Cdc42GAP affirms the critical involvement of Cdc42 in filopodia induction, directed migration, and proliferation in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Mol. Biol. Cell 17:4675-4685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng, Y., S. Bagrodia, and R. A. Cerione. 1994. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity by Cdc42Hs binding to p85. J. Biol. Chem. 269:18727-18730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.