Abstract

Sensitization refers to augmented behavioral responses produced by repeated, intermittent injections of dopaminergic psychostimulants. The locomotor manifestations observed after a sensitizing course of quinpirole, a D2/D3 dopamine agonist, can be modified by the MAOA inhibitor clorgyline, by a mechanism apparently unrelated to its actions on MAOA. Alterations in regional neuronal activity produced by quinpirole in quinpirole-sensitized rats with or without clorgyline pre-treatment were assessed on the basis of LCGU using the [14C]-2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) method. Adult, male Long-Evans rats (180–200 g, n = 9–10/group) were subjected to an injection of either clorgyline (1.0 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline 90 minutes prior to an injection of quinpirole (0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline, 1 set of injections administered every 3rd day for 10 sets. The 2-DG procedure was initiated 60 minutes after an 11th set of injections in freely moving rats. LCGU was determined by quantitative autoradiography. LCGU was decreased in a number of limbic (nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum) and cortical (medial/ventral orbital and infralimbic) regions and in the raphe magnus nucleus in quinpirole-sensitized rats (P < 0.05 v. saline-saline). Quinpirole-sensitized rats pretreated with clorgyline had similar alterations in LCGU, but LCGU was higher in the locus coeruleus compared to quinpirole alone (P < 0.05), was not decreased in the raphe magnus nucleus, and was decreased in the piriform cortex and septum. This implicates altered activity of the noradrenergic, serotonergic, olfactory, and limbic systems in the modified behavioral response to quinpirole with clorgyline pretreatment.

Keywords: Behavioral sensitization, [14C]-2-Deoxyglucose, D2/D3 dopamine receptor, Clorgyline, Quinpirole, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

1. Introduction

Sensitization is a phenomenon produced by dopaminergic psychostimulants in which repeated, intermittent administration produces behavioral responses of greater magnitude than a single, acute dose (Robinson and Becker, 1986). This long-lasting phenomenon is thought to contribute to the development of addiction, with enhanced activation of the mesolimbic dopamine system contributing to the development of drug craving (Robinson and Berridge, 1993). In addition, neuropsychiatric disorders such as mania, multiple chemical sensitivity, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychosis are hypothesized to represent sensitized responses to stimuli such as stressors, electrical stimuli, or chemicals (Di Chiara, 1995; Ellison, 1994; Post and Contel, 1981; Robinson and Berridge, 1993; Rossi, 1996; Szechtman et al., 1998). Although functional changes in the “motive circuit”, which includes the mesolimbic dopamine system, as well as changes in glutamatergic neurotransmission, seem to be a factor in sensitization; the specific mechanisms underlying sensitization remain to be fully elucidated [for review see: (Pierce and Kalivas, 1997; Vanderschuren and Kalivas, 2000; Wolf, 2002)].

Quinpirole is a highly specific direct dopamine agonist at D2 and D3 dopamine receptors (Levant et al., 1992; Tsuruta et al., 1981). In this study, quinpirole was used to study dopamine receptor-mediated mechanisms of sensitization. Although more extensively studied, amphetamine and cocaine are indirect dopamine agonists and thus affect not only multiple dopamine receptors, but also the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems (Jaffe, 1993), which can confound the elucidation of key mechanisms of sensitization produced by both direct and indirect agonists. In addition to their complex pharmacologies, amphetamine and cocaine also induce complex behavioral profiles. Acutely, amphetamine and cocaine produce locomotion at low doses and stereotypy (e.g. intense repetitious chewing, licking, or sniffing) at high doses with the duration and intensity of the stereotypy increases with increasing doses (Pradhan et al., 1978; Roy et al., 1978; Segal, 1975). During a sensitizing course of amphetamine or cocaine, the stereotypy becomes more intense, the time to the onset of the stereotypy becomes shorter, and/or stereotypy develops even at low doses (Bhattacharyya and Pradhan, 1979; Estevez et al., 1979; Kilbey and Ellinwood, 1977; Leith and Kuczenski, 1981; Leith and Kuczenski, 1982; Magos, 1969; Roy et al., 1978; Segal, 1975; Segal and Mandell, 1974; Segal and Schuckit, 1983; White et al., 1998). In contrast, increasing doses of quinpirole enhance locomotion and do not induce stereotypy (Arnt et al., 1987; Eilam and Szechtman, 1989; Longoni et al., 1987). Likewise, the sensitized behavioral response to quinpirole consists of locomotion with little or no stereotypy (Arnt et al., 1987; Eilam and Szechtman, 1989; Longoni et al., 1987). Furthermore, quinpirole-sensitized animals exhibit “checking” behaviors similar observed in humans with OCD and thus may represent an animal model of the disorder (Einat and Szechtman, 1993; 1995; Szechtman et al., 1998; 1999; 2001).

Previously, we have shown that decreased local cerebral glucose utilization (LCGU) in the nucleus accumbens, limbic cortical areas, and other limbic regions are associated with the sensitized locomotor response to quinpirole (Carpenter et al., 2003; Richards et al., 2005). Based on in vitro studies indicating that monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors inhibit the binding of [³H]quinpirole to striatal D2 receptors (Levant et al., 1996; 2001), Culver and colleagues found that the locomotor manifestations observed after a sensitizing course of quinpirole are attenuated by the MAOA inhibitor clorgyline (Culver et al., 2000). Closer behavioral observation showed that pretreatment with clorgyline changes the sensitized response to quinpirole to intense self-directed “mouthing” or grooming behavior suggesting altered changes in underlying neuronal activity (Culver et al., 2000). This change in the sensitized behavioral response to quinpirole may reside in alterations in underlying quinpirole-induced neuronal activity.

To gain insights into the mechanism by which the behavioral effects of quinpirole are modified by clorgyline, the effects of quinpirole-induced sensitization with or without clorgyline pre-treatment on neuronal activity were assessed on the basis of LCGU using the [14C]-2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) method. We will show that neuronal activity in brain regions including the locus coeruleus, raphe magnus nucleus, piriform cortex, and septal area differ between quinpirole-sensitized rats with or without clorgyline pretreatment implicating altered activity of the noradrenergic, serotonergic, olfactory, and limbic systems in the modified behavioral response.

2. Results

Rats were treated with a sensitizing course of quinpirole with or without pretreatment with clorgyline.

2.1. Effects on Locomotor Activity

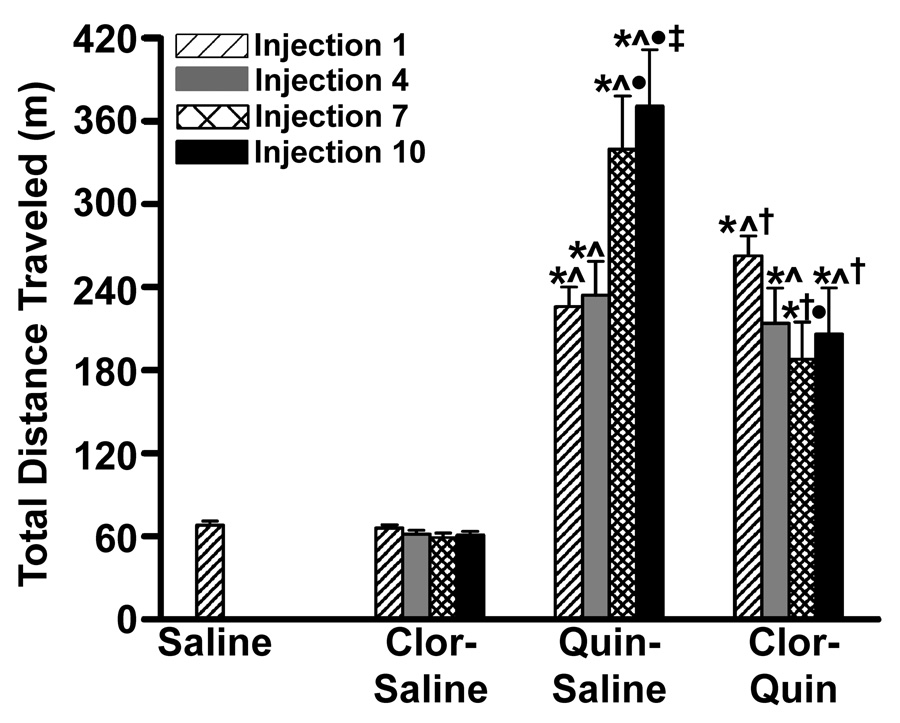

After all injections, rats treated with clorgyline alone (clorgyline-saline) exhibited levels of locomotor activity similar to that observed after a saline injection. Regardless of pretreatment, the initial dose of quinpirole produced a 3-fold increase (P < 0.05) in activity compared to saline control (Figure 1). In the saline-quinpirole rats, the tenth quinpirole injection produced a further 2-fold increase (P < 0.05) in locomotor activity over the initial dose, thus confirming sensitization. Pretreatment with clorgyline (clorgyline-quinpirole) did not alter the increased locomotion produced by a single dose of quinpirole. However, in agreement with other studies (Culver and Szechtman, 1997), clorgyline pretreatment (clorgyline-quinpirole) blocked the enhancement of locomotor activity produced by a sensitizing course of quinpirole. Direct observation confirmed that this decrease in locomotor activity was coincided with the expression of vigorous licking/stroking behavior consistent with the self-directed “mouthing” activity described by Culver and colleagues (Culver et al., 2000).

Fig. 1. Effects of clorgyline pretreatment on quinpirole-induced locomotor activity.

Rats (n = 9–10 per group) were injected with clorgyline (1.0 mg/kg) or saline 90 minutes prior to an injection of quinpirole (0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline, 1 set of injections given every 3rd day for 10 sets. Locomotor activity was quantified for the 2-hour period beginning after quinpirole or saline injections 1, 4, 7, and 10 using a force-plate actometer. * P < 0.05 v. saline; ∧ P < 0.05 v. clorgyline-only for respective injection; † P < 0.05 v. quinpirole-only for respective injection; • P < 0.05 v. injection 1 for respective treatment; ‡ P < 0.05 v. injection 4 for respective treatment by ANOVA and Student-Newman-Keuls test.

2.2. Effects on LCGU

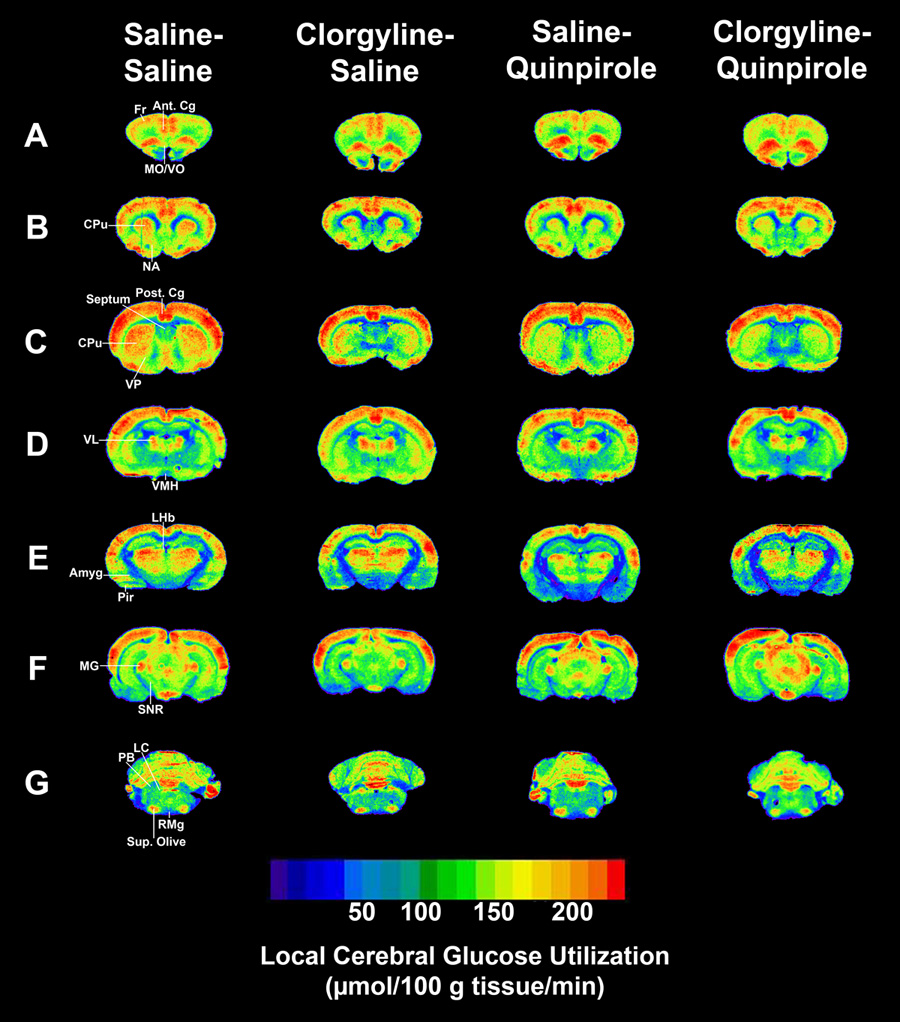

LCGU was determined in 54 brain regions surveying the fore-, mid-, and hind- brain with emphasis on limbic structures, for the 45-minute period beginning 1 hour after quinpirole administration (Table 1, Figure 2). Average cerebral glucose utilization across all brain regions sampled in clorgyline-saline, saline-quinpirole, and clorgyline-quinpirole rats were not significantly different from saline controls indicating that there was no main effect of drug treatment (data not shown).

Table 1.

Effects of clorgyline pretreatment on quinpirole-induced alterations in LCGU in specific brain regions.

| Brain area | LCGU (µmol/100 g tissue/min) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline-Saline | Clorgyline-Saline | Saline-Quinpirole | Clorgyline-Quinpirole | |

| Cortex | ||||

| agranular insular | 144 ± 7 | 119 ± 12 | 114 ± 7 | 118 ± 8 |

| anterior cingulate, 1 | 209 ± 12 | 176 ± 12 | 174 ± 14 | 183 ± 12 |

| anterior cingulate, 3 | 205 ± 11 | 170 ± 17 | 157 ± 14 | 159 ± 12 |

| anterior parietal, 1 | 168 ± 9 | 140 ± 12 | 138 ± 10 | 149 ± 11 |

| frontal, 1 | 163 ± 9 | 133 ± 10 | 142 ± 10 | 152 ± 11 |

| frontal, 2 | 176 ± 10 | 142 ± 10 | 157 ± 12 | 163 ± 12 |

| frontal, 3 | 161 ± 10 | 131 ± 11 | 132 ± 10 | 142 ± 11 |

| infralimbic | 162 ± 9 | 125 ± 11* | 116 ± 9* | 107 ± 6* |

| lateral orbital | 236 ± 11 | 192 ± 17 | 202 ± 16 | 198 ± 15 |

| medial/ventral orbital | 188 ± 9 | 154 ± 15 | 135 ± 10* | 138 ± 8* |

| ventrolateral orbital | 251 ± 13 | 209 ± 19 | 211 ± 18 | 210 ± 14 |

| posterior cingulate | 235 ± 13 | 192 ± 17 | 217 ± 19 | 216 ± 14 |

| piriform | 149 ± 10 | 115 ± 11 | 116 ± 8 | 112 ± 7* |

| posterior parietal | 187 ± 11 | 145 ± 14 | 171 ± 15 | 173 ± 13 |

| entorhinal | 107 ± 5 | 91 ± 8 | 84 ± 7 | 86 ± 4 |

| occipital | 174 ± 10 | 156 ± 13 | 171 ± 18 | 156 ± 6 |

| Caudate/putamen | 188 ± 9 | 152 ± 14 | 139 ± 11* | 136 ± 8* |

| Nucleus accumbens-core | 166 ± 8 | 133 ± 14 | 120 ± 8* | 115 ± 7* |

| Nucleus accumbens-shell | 154 ± 8 | 121 ± 12 | 111 ± 8* | 103 ± 5* |

| Olfactory tubercle | 182 ± 8 | 153 ± 20 | 163 ± 18 | 131 ± 7 |

| Corpus callosum | 84 ± 3 | 68 ± 5 | 65 ± 5* | 63 ± 4* |

| Nucleus of the diagonal band | 148 ± 5 | 111 ± 10 | 130 ± 13 | 119 ± 9 |

| Septal area | 115 ± 6 | 91 ± 8 | 93 ± 8 | 86 ± 4* |

| Ventral pallidum | 122 ± 8 | 87 ± 7* | 91 ± 6* | 83 ± 4* |

| Bed nucleus | 112 ± 7 | 83 ± 7* | 76 ± 5* | 76 ± 3* |

| Globus pallidus | 114 ± 10 | 88 ± 7 | 91 ± 6 | 89 ± 4 |

| Lateral preoptic area | 138 ± 9 | 102 ± 10* | 119 ± 9 | 100 ± 7* |

| Thalamus | ||||

| anterior | 119 ± 11 | 80 ± 9* | 81 ± 11* | 75 ± 6* |

| ventrolateral | 208 ± 12 | 180 ± 20 | 202 ± 22 | 183 ± 16 |

| ventromedial | 178 ± 10 | 143 ± 14 | 148 ± 16 | 143 ± 9 |

| Hypothalamus | ||||

| anterior | 125 ± 10 | 89 ± 8* | 91 ± 6* | 87 ± 4* |

| lateral | 108 ± 4 | 87 ± 8 | 99 ± 10 | 85 ± 9 |

| ventromedial | 115 ± 7 | 82 ± 7* | 85 ± 5* | 83 ± 4* |

| Amygdala | 113 ± 6 | 89 ± 8 | 88 ± 6* | 87 ± 6* |

| Dentate gyrus | 129 ± 6 | 108 ± 12 | 108 ± 8 | 110 ± 6 |

| Lateral habenula | 180 ± 11 | 139 ± 15 | 130 ± 11* | 122 ± 9* |

| Subthalamic nucleus | 105 ± 4 | 82 ± 6 | 90 ± 6 | 99 ± 9 |

| Deep mesencephalic nucleus | 128 ± 7 | 105 ± 8 | 119 ± 11 | 120 ± 7 |

| Hippocampus | 126 ± 6 | 104 ± 9 | 99 ± 8 | 102 ± 5 |

| Medial geniculate nucleus | 172 ± 11 | 158 ± 13 | 167 ± 14 | 171 ± 10 |

| Substantia nigra | 121 ± 7 | 98 ± 7 | 108 ± 9 | 110 ± 8 |

| Ventral tegmental area | 124 ± 8 | 97 ± 8 | 106 ± 7 | 103 ± 7 |

| Central gray | 128 ± 5 | 103 ± 8 | 110 ± 11 | 115 ± 6 |

| Pontine nucleus | 102 ± 5 | 79 ± 8 | 90 ± 8 | 95 ± 4 |

| Superior colliculus | 153 ± 7 | 134 ± 10 | 146 ± 14 | 156 ± 8 |

| Inferior colliculus | 213 ± 13 | 181 ± 14 | 210 ± 16 | 214 ± 17 |

| Lateral superior olive | 186 ± 15 | 150 ± 12 | 172 ± 18 | 190 ± 13 |

| Locus coeruleus | 136 ± 17 | 111 ± 9 | 102 ± 8† | 152 ± 14 |

| Dorsal tegmental nucleus | 135 ± 7 | 97 ± 10* | 108 ± 5 | 119 ± 8 |

| Parabrachial nucleus | 142 ± 15 | 111 ± 18 | 114 ± 12 | 141 ± 14 |

| Raphe magnus nucleus | 88 ± 5 | 70 ± 5 | 67 ± 6* | 78 ± 4 |

| Cerebellum | ||||

| crus 1 ansiform lobule | 138 ± 9 | 114 ± 12 | 153 ± 17 | 144 ± 11 |

| posterior superior lobule | 139 ± 7 | 106 ± 10 | 144 ± 15 | 144 ± 11 |

| vermis | 155 ± 8 | 130 ± 14 | 171 ± 19 | 172 ± 16 |

Rats (n = 9–10 per group) were injected with clorgyline (1.0 mg/kg) or saline 90 minutes prior to an injection of quinpirole (0.5mg/kg, s.c.) or saline, 1 set of injections given every 3rd day for 10 sets. The 2-DG procedure was initiated 60 minutes after an 11th quinpirole or saline injection. Data are expressed as the mean ±S.E.M.

P < 0.05 v. saline-saline

P < 0.05 vs. clorgyline-quinpirole by ANOVA and Tukey-Kramer tests.

Fig. 2. Effects of clorgyline pretreatment on quinpirole-induced alterations in LCGU in specific brain regions.

Rats (n = 9–10 per group) were injected with clorgyline (1.0 mg/kg) or saline 90 minutes prior to an injection of quinpirole (0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline, 1 set of injections given every 3rd day for 10 sets. The 2-DG procedure was initiated 60 minutes after an 11th quinpirole or saline injection. (A) Bregma 3.70 mm. (B) Bregma 1.70 mm. (C) Bregma 0.20 mm. (D) Bregma −2.30 mm. (E) Bregma −3.60 mm. (F) Bregma −6.04. (G) Bregma −9.80. Fr-frontal cortex. Ant. Cg-anterior cingulate cortex. MO/VO-medial/ventral orbital cortex. CPu-caudate/putamen. NA-nucleus accumbens. Post Cg-posterior cingulate cortex. VP-ventral pallidum. VL-ventrolateral thalamus. VMH-ventromedial hypothalamus. LHb-lateral habenula. Amgy-amygdala. Pir-piriform cortex. MG-medial geniculate. SNR-substantia nigra. LC-locus coeruleus. PB-parabrachial nucleus. Sup. Olive-superior olive. RMg-raphe magnus nucleus.

In rats treated with clorgyline alone (clorgyline-saline), LCGU was decreased 26–33% compared to control (saline-saline) (P < 0.05) in the infralimbic cortex, ventral pallidum, bed nucleus stria terminalis, lateral preoptic area, anterior thalamus, anterior hypothalamus, ventromedial hypothalamus, and dorsal tegmental nucleus.

In quinpirole-sensitized rats (saline-quinpirole), LCGU was decreased 23–32% compared to controls (saline-saline) (P < 0.05) in the infralimbic cortex, medial/ventral orbital cortex, caudate/putamen, nucleus accumbens core and shell, corpus callosum, ventral pallidum, bed nucleus stria terminalis, anterior thalamus, anterior hypothalamus, ventromedial hypothalamus, amygdala, lateral habenula, and raphe magnus nucleus.

LCGU in quinpirole-sensitized rats pretreated with clorgyline (clorgyline-quinpirole) was similar to that observed in sensitized rats without pretreatment (saline-quinpirole); however, there were a few important differences. In clorgyline-quinpirole rats, LCGU was decreased compared to saline-saline rats (P < 0.05) in the lateral preoptic area (−28%), piriform cortex (−25%), and septal area (−25%), but was not different in the raphe magnus nucleus. In addition, LCGU was increased 49% in the locus coeruleus compared to saline-quinpirole rats (P < 0.05).

3. Discussion

Pretreatment with clorgyline, a drug most noted for its activity as an MAOA inhibitor, changes the sensitized response to quinpirole from locomotion to stationary “mouthing” activity (Culver et al., 2000) by a yet-to-be fully elucidated mechanism unrelated to its actions at MAOA (Culver et al., 2000; Levant et al., 1996; 2001). To elucidate what neuronal systems may be involved in this change in sensitized behavior, this study examined the effects of clorgyline pretreatment on quinpirole-induced alterations in LCGU. LCGU was assessed using the 2-DG procedure which measures the net changes in glucose uptake over the entire neuronal population sampled and correlates with neuronal activity. LCGU (Sokoloff et al., 1977). Although a sensitive and well-validated tool for elucidating neuronal pathways affected by a stimulus, it must be noted that the 2-DG procedure alone cannot identify the specific neurotransmitters or receptor types involved nor can it differentiate between the neurons directly affected by the drug stimulus and those elsewhere in the affected neuronal circuitry. Likewise, the technique measures the net neuronal activity resulting from both the drug action(s) producing the behavioral effect and the consequent somatosensory input from the periphery, effects that cannot be differentiated without introducing additional experimental confounds.

3.1. Effects of Clorgyline or Quinpirole alone on LCGU

Consistent with inhibition of monoamine catabolism and previous studies (Gerber et al., 1983; Palombo et al., 1991), treatment with clorgyline alone produced alterations in LCGU in limbic brain regions, where high concentrations of monoamines are present such as in the bed nucleus stria terminalis, and in thalamic and hypothalamic areas, which have neuronal connections with the limbic system. Clorgyline produced no alterations in locomotor activity, so these changes in LCGU appear to be unrelated to motor activation of the rat.

Treatment with a sensitizing course of quinpirole decreased LCGU in the nucleus accumbens, limbic cortical regions, and other limbic associated regions and did not change LCGU in the locus coeruleus when compared to controls, in agreement with our previous studies (Carpenter et al., 2003; Richards et al., 2005). These changes in LCGU are consistent with activation of the “motive circuit”, a central mechanism proposed for the neurobiological basis of sensitization [for review see: (Pierce and Kalivas, 1997; Vanderschuren and Kalivas, 2000; Wolf, 2002)]. In the present study, treatment with a sensitizing course of quinpirole also decreased LCGU in the corpus callosum, bed nucleus stria terminalis, anterior thalamus, anterior hypothalamus, ventromedial hypothalamus, amygdale, and raphe magnus nucleus when compared to controls. Effects in these regions were not seen in our previous studies (Carpenter et al., 2003; Richards et al., 2005); however, increased sample size in the current study, leading to increased statistical power, may have contributed to these differences.

3.2. Effects of Clorgyline Pretreatment on Quinpirole-induced Alterations in LCGU

The alteration in the quinpirole-induced behavioral response by clorgyline pretreatment should reflect changes in underlying neuronal activity. Clorgyline pretreatment could modify quinpirole-induced behavior by blocking sensitization with a concomitant attenuation of the quinpirole-induced effects on LCGU. Alternatively, clorgyline pretreatment may further enhance sensitization. It is generally thought that as sensitization is enhanced, the behavioral response changes from one of locomotion to one of stereotyped sniffing/licking and then to one of biting/gnawing (Mogilnicka and Braestrup 1976; Mueller 1983). For example, as amphetamine-induced sensitization develops, the behavioral response is changed from locomotor activity to oral stereotypy (Segal and Schuckit, 1983). In this case, changes in LCGU of greater magnitude might be expected. On the other hand, clorgyline pretreatment could modify the sensitized response resulting in differences in the brain regions affected or complex interactions of both magnitude of effect and regions affected.

Alterations in LCGU in quinpirole-sensitized rats with clorgyline pretreatment were generally similar in both regional distribution and magnitude to those in quinpirole-sensitized rats without pretreatment even though pretreatment with clorgyline produced a dramatic change in the behavioral response. However, differences in LCGU were observed in a few key brain regions between quinpirole-sensitized rats with and without clorgyline pretreatment. Specifically, in quinpirole-sensitized rats pretreated with clorgyline, LCGU was decreased in the lateral preoptic area, piriform cortex, and septal area and was not decreased in the raphe magnus nucleus when compared to controls. In addition, LCGU was increased in the locus coeruleus compared to quinpirole alone. Of these, the difference in LCGU in the lateral preoptic area, where treatment with clorgyline alone decreased LCGU, can be attributed to the effects of clorgyline and presumably to increased synaptic availability of serotonin and/or norepinephrine. On the other hand, the differences in LCGU in the piriform cortex, septal area, raphe magnus nucleus, and locus coeruleus indicate a modification of the effects of quinpirole by clorgyline.

While it is possible that the combination of clorgyline and quinpirole leads to a more amphetamine-like state or that there is some interaction occurring between inhibited monoamine oxidase activity and noradrenergic transmission, a variety of evidence suggests that this is not necessarily the case. For example, even though clorgyline increases synaptic availability of serotonin and norepinephrine through inhibition of MAOA, the changes in LCGU in these brain regions probably are not due to activity at MAOA since these changes were not seen with clorgyline alone. In addition, moclobemide, an MAOA inhibitor with low affinity for blocking quinpirole binding (Levant et al., 1996), fails to block the locomotor response to quinpirole while producing similar inhibition of MAOA (Culver et al., 2000). Clorgyline also modulates [³H]quinpirole binding in the absence of MAOA (Levant et al., 2001). Furthermore and consistent with in vitro findings (Levant et al., 1993; 1996), modulation of dopamine uptake and interactions with the sigma and imidazoline sites have also been eliminated as potential mediators of clorgyline’s actions in this model (Culver et al., 2002; Culver and Szechtman, 2003). Accordingly, it has been hypothesized that clorgyline modulates [³H]quinpirole binding to the D2 receptor and quinpirole-induced behavior via either allosteric interactions or interaction at a novel, non-MAO binding site (Levant, 2002); however, future studies must determine the actual underlying mechanism.

Quinpirole-sensitized rats with clorgyline pretreatment had decreases in LCGU of greater magnitude, reaching statistical significance compared to controls, in the piriform cortex and septal area than with quinpirole alone indicating a more robust involvement of these limbic regions in the modified behavioral response. The piriform cortex receives input from the olfactory bulb, and in turn, sends projections via the thalamus to the medial orbital cortex, which, among other things, plays a role in the discrimination of odors (Buck, 2000; Elliott et al., 2000). The septal area also has connections with the olfactory bulb further suggesting involvement of olfactory function in the modified behavioral response. In addition, the septal area has reciprocal connections with limbic and other brain regions such as the hypothalamus, brainstem, hippocampus, amygdala, and cortex and plays a role in learning and memory, emotions, stress, and autonomic functions (Jakab and Leranth, 1995). In view of our previous findings that a sensitized behavioral response to quinpirole involves more widespread decreases in LCGU in the limbic system than that produced by a single dose of quinpirole (Carpenter et al., 2003; Richards et al., 2005), this further increase in the number of limbic brain regions affected after clorgyline pretreatment suggests that some augmentation of sensitization may be occurring.

Clorgyline pretreatment decreased the effects of quinpirole sensitization on LCGU in the raphe magnus nucleus. The raphe magnus nucleus, one of the descending raphe nuclei that gives rise to serotonergic projections to the brain stem and spinal cord that are involved in motor system tone and pain perception (Saper, 2000); thus, implicating these projections and serotonergic mechanisms in the change from locomotion to grooming activity. The raphe magnus nucleus receives input from other raphe nuclei including the dorsal and median raphe nuclei (Frazer and Hensler, 1999). Blockade of D2 dopamine receptors in the dorsal raphe nucleus augments quinpirole-induced locomotor activation, suggesting that stimulation of the receptors suppresses this locomotor behavior (Szumlinski and Szechtman, 2002). The dorsal raphe nucleus also appears important in the acute effects of cocaine; however, the median raphe nucleus appears to be important in sensitized behavioral responses (Szumlinski et al., 2004). These findings suggest complex interactions of the raphe nuclei are integrally involved in modulating quinpirole-induced behaviors that must be elucidated in future studies.

Finally, the difference in LCGU of the greatest magnitude between quinpirole-sensitized rats with and without clorgyline pretreatment, and thus the difference with the greatest potential for functional importance, was observed in the locus coeruleus. The locus coeruleus, the major noradrenergic perikarya, has numerous efferent projections to brain regions such as the olfactory bulb, olfactory cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, striatum, cingulate, motor, and orbital cortices, bed nucleus stria terminalis, septum, preoptic area, hypothalamus, cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord (Aston-Jones et al., 1995). These noradrenergic projections play a role in arousal including psychostimulant-induced arousal, sensory perception, motor tone, and responsiveness to novel stimuli (Berridge, 2006; Saper, 2000). The locus coeruleus appears to have two modes of function: the phasic mode, which is important for optimizing task performance in order to keep receiving the greatest amount of reward (exploitation) and the tonic mode, which is important for adapting to a novel or changing environment and finding new rewards (exploration). Changes in activity of afferent connections to the locus coeruleus or alterations in activity within the locus coeruleus (e.g., activation/inhibition of noradrenergic autoreceptors) can influence whether the locus coeruleus is in the tonic or phasic mode (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). It is interesting to hypothesize that a change in locus coeruleus activity from the tonic to phasic modes could underlie the modification of quinpirole-induced behavior with clorgyline pretreatment; however, this must be determined in future studies.

3.3. Relevance to Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

OCD is a chronic and complex psychiatric disorder with a estimated lifetime prevalence rate of 1–3% in humans (Weissman et al., 1994) involving repetitive, senseless, and persistent obsessions (images, thoughts, or impulses) and/or compulsions (behaviors done to alleviate anxiety or prevent a dreaded event) that significantly interfere with a person’s daily functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Common obsessions include excessive and senseless worrying about contamination, harming oneself and/or others, order and precision, and saving with the complementary compulsions being excessive and repetitive washing, checking, arranging, and hoarding, respectively (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Altered activities of the cortico-striatal-thalamic circuits along with the serotonergic and dopaminergic systems reportedly play a role in the pathogenesis of OCD (Stein, 2002). However, the exact mechanisms underlying the disorder are still not fully understood. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors are used in the treatment of OCD, but improvement rates are only between 20–60% (Piccinelli et al., 1995). Furthermore, it is not fully understood why OCD patients differ in their particular obsession and/or compulsion (McKay et al., 2004) or why the obsession and/or compulsion changes over time in almost 2/3 of patients (Skoog and Skoog, 1999). Answering these question would greatly aid in the understanding of underlying mechanisms and treatment of this disorder.

Interestingly, quinpirole-sensitized animals exhibit behaviors, such as revisiting objects and places more often with shorter time periods between visits and fewer visits elsewhere than controls and increased perseveration in other tasks, that are comparable to compulsive checking behaviors seen in humans with OCD (Einat and Szechtman, 1993; 1995; Szechtman et al., 1998; 1999; Szechtman et al., 2001). Szechtman and colleagues also observed that quinpirole-sensitized rats engage in distinct motor routines at the favored object/place (Szechtman et al., 1998; 1999) similar to ritual-like routines seen in OCD patients (Marks, 1987). Furthermore, quinpirole-sensitized rats persist in revisiting the favored object even if the location is changed (Szechtman et al., 1998; 1999) consistent with clinical observations that eliminating the object being checked does not attenuate the checking behavior in OCD (Rasmussen and Eisen, 1991). In addition, clomipramine, a serotonin uptake inhibitor used to treat OCD in humans, transiently decreased the checking behaviors in quinpirole-sensitized rats (Szechtman et al., 1998; 1999) analogous to improvement rates observed in OCD patients (Piccinelli et al., 1995).

In the quinpirole sensitization model, pretreatment with clorgyline induces a behavioral change from locomotion to stationary, “mouthing” (Culver et al., 2000) or grooming activity providing a novel way to extend the quinpirole sensitization model to one that better reflects the variance seen in human OCD behaviors. Therefore, the present data suggest that the piriform cortex, septal area, raphe magnus nucleus, and the locus coeruleus, which differed between the quinpirole-sensitized rats with and without clorgyline pretreatment, might represent regions involved in the pathogenesis of OCD. However, although human imaging studies have consistently shown alterations in neuronal activity in the cingulate cortex, orbital cortex, and caudate putamen of OCD patients, to date, the regions identified in this study have not been examined to date [for review see: (Friedlander and Desrocher, 2006)].

4.4. Conclusions

Quinpirole-sensitized rats with or without clorgyline pretreatment had similar alterations in LCGU associated with the limbic motive circuitry but differed in the piriform cortex, septal area, raphe magnus nucleus, and locus coeruleus. The relatively small differences in affected brain regions suggest that clorgyline is modifying the sensitized response to quinpirole although some augmentation or attenuation of sensitization may also be occurring in some brain regions. The brain regions differentially affected by clorgyline pretreatment are part of the olfactory, limbic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic systems, respectively. The locus coeruleus appears to be of greatest potential importance because this region had the biggest difference in magnitude in LCGU between quinpirole sensitized rats with and without clorgyline pretreatment and exhibits tonic and phasic patterns of activity that could underlie the change in behavior (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005). Further studies must assess if specific neurochemical, pharmacodynamic, or environmental stimuli trigger/underlie these behaviors.

4. Experimental Procedure

4.1. Sensitization treatment

Research was performed in compliance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996). Adult, male, Long-Evans rats (180–200 g; n=9–10; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were acclimated to the animal facility for five days prior to the start of experiments. During the acclimatization period, rats were handled once per day. The two days prior to the start of the experiments, rats were brought to the laboratory and placed in the forced plate actometer for two hours receiving no injection the first time and a saline injection the second time in which behavior was analyzed during for use as a baseline measure.

During the experiments, rats were brought to a dedicated treatment/testing room isolated from other activity and noise at the same time each day. Rats were injected with clorgyline (1 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline 90-minutes prior to an injection of quinpirole (0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) or saline, 1 set of injections were given every third day, based on the procedures of Culver and colleagues (2000). To verify sensitization, locomotor activity was assessed after injections 1, 4, 7 and 10 using a force-plate actometer on the basis of distance traveled (Fowler et al., 2001). Although other types of behaviors were not quantitatively assessed in this study, video-taped actometer sessions were qualitatively evaluated for the presence of other behaviors. Because quinpirole sensitization is at least partly environment-dependent (Szechtman et al., 1993; Van Hartesveldt, 1997) and the 2-DG procedure cannot be performed in the force-plate actometer, each rat was placed in a 30 cm × 56 cm × 30 cm plastic box after all other injections so that the 2-DG procedure could be performed under conditions similar to the sensitized environment. The force-plate actometer and plastic boxes were thoroughly cleaned after each animal. The 2-DG procedure was performed after the eleventh set of injections. Behavioral data were analyzed for statistically significant effects by ANOVA and the Student-Newman-Keuls tests. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

4.2. 2-Deoxyglucose Procedure

LCGU was measured using the 2-DG procedure of Sokoloff and colleagues (Sokoloff et al., 1977) in freely moving rats as previously described (Carpenter et al., 2003; Levant et al., 1998; Levant and Pazdernik, 2004). The day prior to the 2-DG procedure, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital and the femoral vein and artery were cannulated and allowed to recover overnight. The next day, rats were treated with the eleventh set of injections (quinpirole or saline with or without clorgyline pre-treatment). Immediately after the quinpirole injection, the rats were placed in a plastic box and left there for the remainder of the experiment. Locomotor activity was not assessed during the 2-DG procedure. Ten minutes prior to the administration of 2-DG, 150 U of heparin was injected (i.v.) and control arterial blood samples were collected. LCGU was determined for the 45-minute period beginning 1 hour after quinpirole or saline administration because quinpirole produces the most robust increases in locomotor activity in the second hour after administration (Eilam and Szechtman, 1989; Van Hartesveldt, 1997). This time period also corresponds with peak plasma quinpirole levels (t1/2 = 9.5 hrs in rats) (Whitaker and Lindstrom, 1987). 2-DG (100 µCi/kg; 55 mCi/mmol; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) was administered as a pulse in 0.9% saline via the venous cannula followed immediately by a flush with saline. Six timed arterial blood samples (50 µL) were collected in heparinized tubes during the first minute immediately following the pulse. Arterial blood samples were then collected every 5 minutes, for a total of 24 samples. Rats were decapitated 45-minutes after administration of 2-DG. Brains were rapidly removed, frozen in isopentane, and stored at −70°C. Coronal brain sections (20 µm) were cut using a cryostat, put on glass cover slips, and immediately dried. Slide-mounted sections were then apposed to Kodak Biomax MR X-ray film for 4 days with [14C]-methylmethacrylate radioactivity standards. Autoradiographic images were digitized and quantified using Scion Image version 4.0.2. Best-fit curves of optical density generated by the [14C]-methylmethacrylate autoradiographic standards resulted when an exponential plot was used to describe the relationship between optical density and radioactivity. Brain regions were identified according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1986) and sampled bilaterally. The average of readings from 3 sections for each brain region from each rat, along with plasma glucose levels and [14C] concentrations, were used to calculate the rate of LCGU according to the Sokoloff equation (Sokoloff et al., 1977). LCGU in specific brain regions is expressed as µmol glucose/100 g tissue/min. Results from each group are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. LCGU data were analyzed for statistically significant effects by ANOVA and Tukey-Kramer tests. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Robert S. Cross for expert technical assistance. This research was supported by KUMC Research Inst. Lied Endowment and NIH P30 HD02528 and P20 RR016475 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources.

Abbreviations

- 2-DG

[14C]-2-deoxyglucose

- LCGU

Local cerebral glucose utilization

- MAO

Monoamine oxidase

- OCD

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, A. P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. vol. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arnt J, Hyttel J, Perregaard J. Dopamine D1 receptor agonists combined with the selective D2 agonist quinpirole facilitate the expression of oral stereotyped behaviour in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;133:137–145. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Shipley MT, Grzanna R. The locus coeruleus, A5 and A7 noradrenergic cell groups. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. vol. Academic Press; 1995. pp. 183–213. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW. Neural substrates of psychostimulant-induced arousal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2332–2340. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya AK, Pradhan SN. Interactions between motor activity and sterotypy in cocaine-treated rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1979;63:311–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00433569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck LB. Smell and taste: the chemical senses. In: Kandel ER, et al., editors. Principles of Neural Science. vol. McGraw-Hill; 2000. pp. 625–647. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter TL, Pazdernik TL, Levant B. Differences in quinpirole-induced local cerebral glucose utilization between naive and sensitized rats. Brain Res. 2003;964:295–301. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver KE, Rosenfeld JM, Szechtman H. A switch mechanism between locomotion and mouthing implicated in sensitization to quinpirole in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;151:202–210. doi: 10.1007/s002139900346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver KE, Rosenfeld JM, Szechtman H. Monoamine oxidase inhibitor-induced blockade of locomotor sensitization to quinpirole: role of striatal dopamine uptake inhibition. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:385–393. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver KE, Szechtman H. Monoamine oxidase inhibitor sensitive site implicated in sensitization to quinpirole. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;339:109–111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01386-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver KE, Szechtman H. Clorgyline-induced switch from locomotion to mouthing in sensitization to the dopamine D2/D3 agonist quinpirole in rats: role of sigma and imidazoline I2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;167:211–218. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1408-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G. The role of dopamine in drug abuse viewed from the perspective of its role in motivation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;38:95–137. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01118-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilam D, Szechtman H. Biphasic effect of D2 agonist quinpirole on locomotion and movements. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;161:151–157. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einat H, Szechtman H. Longlasting consequences of chronic treatment with the dopamine agonist quinpirole for the undrugged behavior of rats. Behav Brain Res. 1993;54:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90046-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einat H, Szechtman H. Perseveration without hyperlocomotion in a spontaneous alternation task in rats sensitized to the dopamine agonist quinpirole. Physiol Behav. 1995;57:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00209-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Dissociable functions in the medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex: evidence from human neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:308–317. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison G. Stimulant-induced psychosis, the dopamine theory of schizophrenia, and the habenula. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1994;19:223–239. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez VS, Ho BT, Englert LF. Metabolism correlates of cocaine-induced stereotypy in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1979;10:267–271. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(79)90099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SC, Birkestrand BR, Chen R, Moss SJ, Vorontsova E, Wang G, Zarcone TJ. A force-plate actometer for quantitating rodent behaviors: illustrative data on locomotion, rotation, spatial patterning, stereotypies, and tremor. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;107:107–124. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer A, Hensler J. Serotonin. In: Siegel GJ, et al., editors. Basic Neurochemistry. vol. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander L, Desrocher M. Neuroimaging studies of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults and children. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:32–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber JC, 3rd, Choki J, Brunswick DJ, Reivich M, Frazer A. The effect of antidepressant drugs on regional cerebral glucose utilization in the rat. Brain Res. 1983;269:319–325. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe JH. Drug addiction and drug abuse. In: Gilman AG, et al., editors. The pharmacological basis of pharmacology. vol. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1993. pp. 522–573. [Google Scholar]

- Jakab RL, Leranth C. Septum. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. vol. Academic Press; 1995. pp. 405–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbey MM, Ellinwood EH., Jr. Reverse tolerance to stimulant-induced abnormal behavior. Life Sci. 1977;20:1063–1075. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(77)90294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leith NJ, Kuczenski R. Chronic amphetamine: tolerance and reverse tolerance reflect different behavioral actions of the drug. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1981;15:399–404. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(81)90269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leith NJ, Kuczenski R. Two dissociable components of behavioral sensitization following repeated amphetamine administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982;76:310–315. doi: 10.1007/BF00449116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B. Novel drug interactions at D2 dopamine receptors: modulation of [³H]quinpirole binding by monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Life Sci. 2002;71:2691–2700. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B, Cross RS, Pazdernik TL. Alterations in local cerebral glucose utilization produced by D3 dopamine receptor-selective doses of 7-OH-DPAT and nafadotride. Brain Res. 1998;812:193–199. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00924-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B, Grigoriadis DE, DeSouza EB. Characterization of [³H]quinpirole binding to D2-like dopamine receptors in rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:929–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B, Grigoriadis DE, DeSouza EB. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors inhibit [³H]quinpirole binding in rat striatal membranes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;246:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(93)90095-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B, Moehlenkamp JD, Morgan KA, Leonard NL, Cheng CC. Modulation of [³H]quinpirole binding in brain by monoamine oxidase inhibitors: evidence for a potential novel binding site. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B, Morgan KA, Ahlgren-Beckendorf JA, Grandy DK, Chen K, Shih JC, Seif I. Modulation of [³H]quinpirole binding at striatal D2 dopamine receptors by a monoamine oxidaseA-like site: evidence from radioligand binding studies and D2 receptor- and MAOA-deficient mice. Life Sci. 2001;70:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B, Pazdernik TL. Differential effects of ibogaine on local cerebral glucose utilization in drug-naive and morphine-dependent rats. Brain Res. 2004;1003:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longoni R, Spina L, Di Chiara G. Permissive role of D1 receptor stimulation for the expression of D2 mediated behavioral responses: a quantitative phenomenological study in rats. Life Sci. 1987;41:2135–2145. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magos L. Persistence of the effect of amphetamine on stereotyped activity in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1969;6:200–201. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(69)90220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks IM. Fears, Phobias, and Rituals: Panic, Anxiety Their Disorders. vol. New York: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McKay D, Abramowitz JS, Calamari JE, Kyrios M, Radomsky A, Sookman D, Taylor S, Wilhelm S. A critical evaluation of obsessive-compulsive disorder subtypes: symptoms versus mechanisms. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:283–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory animals. vol. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Palombo E, Porrino LJ, Crane AM, Bankiewicz KS, Kopin IJ, Sokoloff L. Cerebral metabolic effects of monoamine oxidase inhibition in normal and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine acutely treated monkeys. J Neurochem. 1991;56:1639–1646. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. vol. Sydney: Academic Press; 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinelli M, Pini S, Bellantuono C, Wilkinson G. Efficacy of drug treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder. A meta-analytic review. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:424–443. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kalivas PW. A circuitry model of the expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine-like psychostimulants. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:192–216. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Contel NR. Cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization: a model for recurrent manic illness. In: Perris C, et al., editors. Biological Psychiatry. vol. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1981. pp. 746–749. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan S, Roy SN, Pradhan SN. Correlation of behavioral and neurochemical effects of acute administration of cocaine in rats. Life Sci. 1978;22:1737–1743. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90626-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S, Eisen JL. Phenomenology of OCD: clinical subtypes, heterogeneity and coexisitence. In: Zohar J, et al., editors. The Psychobiology of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. vol. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1991. pp. 13–43. [Google Scholar]

- Richards TL, Pazdernik TL, Levant B. Altered quinpirole-induced local cerebral glucose utilization in anterior cortical regions in rats after sensitization to quinpirole. Brain Res. 2005;1042:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Becker JB. Enduring changes in brain and behavior produced by chronic amphetamine administration: a review and evaluation of animal models of amphetamine psychosis. Brain Res. 1986;396:157–198. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(86)80193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi J., 3rd Sensitization induced by kindling and kindling-related phenomena as a model for multiple chemical sensitivity. Toxicology. 1996;111:87–100. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(96)03394-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy SN, Bhattacharyya AK, Pradhan SN. Behavioural and neurochemical effects of repeated administration of cocaine in rats. Neuropharmacology. 1978;17:559–564. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(78)90148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB. Brain stem modulation of sensation, movement, and consciousness. In: Kandel ER, et al., editors. Principles of Neural Science. vol. McGraw-Hill; 2000. pp. 889–909. [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS. Behavioral and neurochemical correlates of repeated d-amphetamine administration. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1975;13:247–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Mandell AJ. Long-term administration of d-amphetamine: progressive augmentation of motor activity and stereotypy. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1974;2:249–255. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(74)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Schuckit MS. Animal models of stimulant-induced psychosis. In: Creese I, editor. Neurochemical, Behavioral and Clincal Perspectives. vol. New York: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 131–167. [Google Scholar]

- Skoog G, Skoog I. A 40-year follow-up of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:121–127. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, Des Rosiers MH, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD, Sakurada O, Shinohara M. The [14C]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem. 1977;28:897–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DK. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. 2002;360:397–405. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szechtman H, Culver K, Eilam D. Role of dopamine systems in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): implications from a novel psychostimulant-induced animal model. Pol J Pharmacol. 1999;51:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szechtman H, Eckert MJ, Tse WS, Boersma JT, Bonura CA, McClelland JZ, Culver KE, Eilam D. Compulsive checking behavior of quinpirole-sensitized rats as an animal model of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder(OCD): form and control. BMC Neurosci. 2001;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szechtman H, Sulis W, Eilam D. Quinpirole induces compulsive checking behavior in rats: a potential animal model of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1475–1485. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.6.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szechtman H, Talangbayan H, Eilam D. Environmental and behavioral components of sensitization induced by the dopamine agonist quinpirole. Behav Pharmacol. 1996;4:405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumlinski KK, Frys KA, Kalivas PW. Dissociable roles for the dorsal and median raphe in the facilitatory effect of 5-HT1A receptor stimulation upon cocaine-induced locomotion and sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1675–1687. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumlinski KK, Szechtman H. D2 receptor blockade in the dorsal raphe increases quinpirole-induced locomotor excitation. Neuroreport. 2002;13:563–566. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200204160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruta K, Frey EA, Grewe CW, Cote TE, Eskay RL, Kebabian JW. Evidence that LY-141865 specifically stimulates the D2 dopamine receptor. Nature. 1981;292:463–465. doi: 10.1038/292463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hartesveldt C. Temporal and environmental effects on quinpirole-induced biphasic locomotion in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58:955–960. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Kalivas PW. Alterations in dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization: a critical review of preclinical studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;151:99–120. doi: 10.1007/s002130000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Lee CK, Newman SC, Oakley-Browne MA, Rubio-Stipec M, Wickramaratne PJ, et al. The cross national epidemiology of obsessive compulsive disorder. The Cross National Collaborative Group. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;(55 Suppl):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker NG, Lindstrom TD. Disposition and biotransformation of quinpirole, a new D2 dopamine agonist antihypertensive agent, in mice, rats, dogs, and monkeys. Drug Metab Dispos. 1987;15:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White IM, Doubles L, Rebec GV. Cocaine-induced activation of striatal neurons during focused stereotypy in rats. Brain Res. 1998;810:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00905-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME. Addiction: making the connection between behavioral changes and neuronal plasticity in specific pathways. Mol Interv. 2002;2:146–157. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]